24

Alone No More

FOR SEVERAL WEEKS NOW, the war had been over. I had spent years hiding underground, concerned with little more than my own survival. Now I was faced with the task of learning to live in the aftermath of war, with no threats to my life or liberty. I was staying with Alex and Anni, resting and recovering and looking to the future. Gradually, I became used to feeling secure, having enough food, and sleeping in a regular bed.

As I grew stronger and my body filled out under the influence of Anni’s cooking, my patience with life in the quiet Lübars countryside grew thin. Although I had never stopped thinking about my parents, their whereabouts now became an obsession. I was also very concerned about Ilse. I had heard nothing from her since her arrest by the Gestapo and felt compelled to search out word of her fate.

So one day, I left for Berlin, heading to Oranienburger Strasse synagogue, the largest and most beautiful synagogue in the city. It seemed to me that the most likely place to begin my search would be there, where Jews would likely congregate.

When I arrived there, I was stunned by what I saw. Almost all of what had been one of the most beautiful buildings in Berlin had been destroyed. I later learned that the damage was caused by a combination of Allied bombing raids and the events of Kristallnacht.

There was a small building near the ruins of the synagogue that served as a temporary office for the Jewish community center (Jüdische Gemeinde). Holocaust survivors filled the building, busy filling out registration forms. The Gemeinde used these forms to record names and addresses that relatives could use to help locate lost friends and family members. The office was like a beehive, with swarms of people talking, yelling, shaking hands, hugging, and crying.

Almost everyone had been marked by the war. Clothing hung loosely on frames that were gaunt and haggard, having been reduced almost to shadows by privation and fear. But the atmosphere was warm and reassuring. It had been a long time since I been in the presence of a group of people containing not a single Nazi agent and even longer since I had been around a large number of my fellow Jews. It was almost overwhelming to be free, not starving, not hunted; gathered in peace with others of my religion.

There were refugees from every corner of Europe: Jews from Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and, of course, Germany. Most spoke Yiddish, a language I understood only imperfectly. For whatever reason, they had all wound up in Berlin, seeking families that had been scattered to the winds.

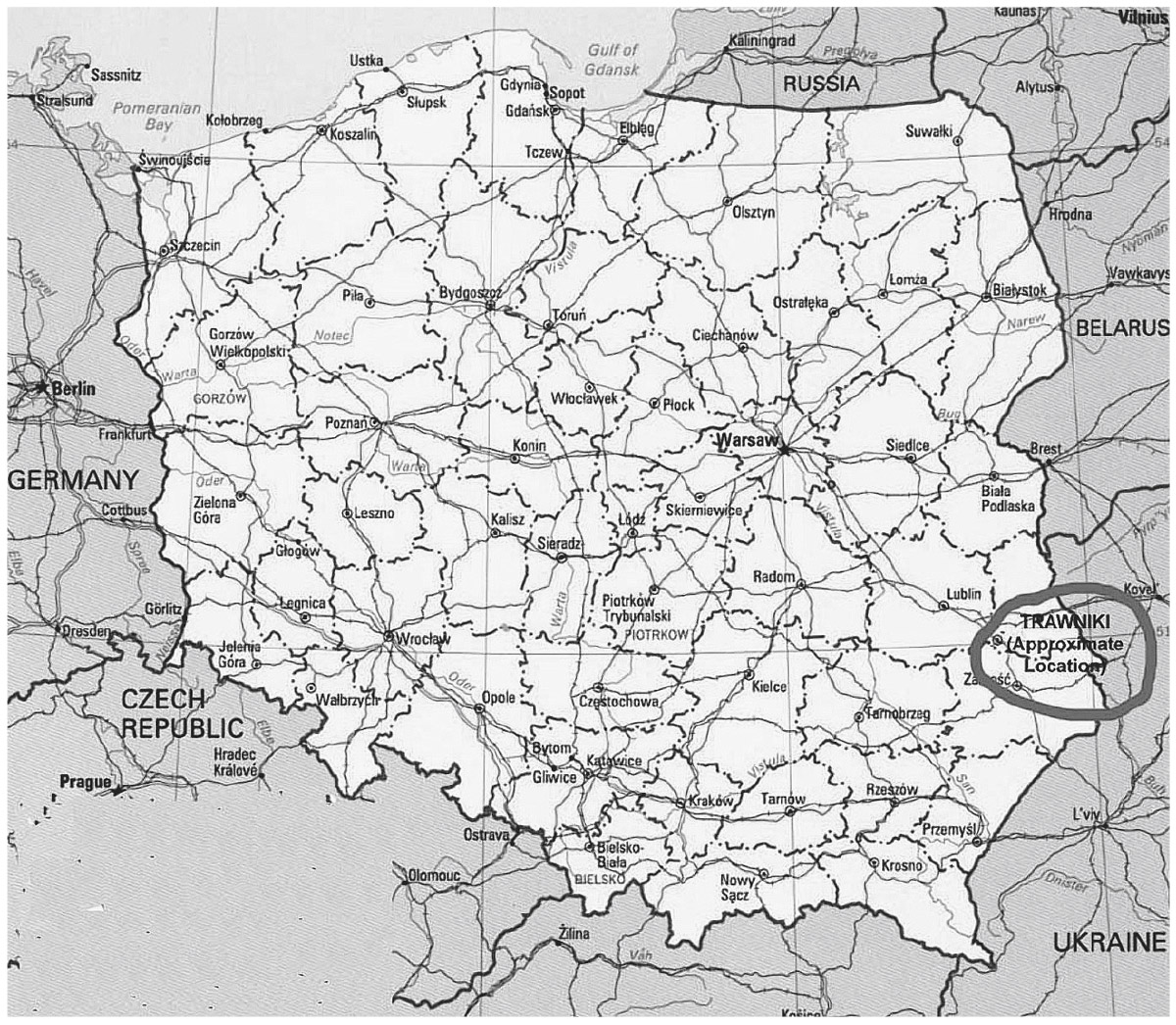

I talked to as many of them as possible, always seeking information about Trawniki, the concentration camp in Poland to which my parents had been deported in 1942. Up until this point, everything I had heard about the camps had been rumors. They were said to be places of death, execution camps for Jews. To my utter horror, eyewitnesses told me that Jews had been killed by the thousands and, as I later learned, the death toll eventually reached into the millions. They were starved to death, worked to death, gassed, beaten, and burned to death.

Among all the refugees crowding into the community center, I found not one person who knew anything about the Trawniki camp. For a time, I carried a sign saying LOOKING FOR THE LEWINS. I still held tightly to the hope that my parents would return, that they would show up in Berlin looking for me. The day wore on and I continued asking everyone I met if they had any information about the Trawniki camp, with no success.

As I left the community center office to go back to Lübars, I mulled over what I had learned. It now appeared that finding my parents would be neither quick nor easy. There was too much chaos, too many people, and too few resources. To my extreme disappointment, no one I met had been interned at Trawniki. Not a soul. The world was now learning the true nature of the Nazi “relocation” camps, and the odds that my parents had survived their internment were poor.

Every few days, I went back to the community center to check for word of my parents. Although the center continued to be filled with people searching for information about their relatives, I saw no one I knew. I didn’t recognize a soul. Little by little, I began to lose hope. I sank into a depression so deep that I soon lost the desire to talk to anyone. Alex and Anni were aware of my mounting despair, but there was little they could do to help. At the community center, I talked to refugees who were in the same situation as myself, searching for lost relatives. There were quite a few people, but their efforts to find their missing family members rarely amounted to anything. There was an odd reunion or two, mostly of people who had been in the same concentration camps together. Very few found any relatives. Hitler’s death machine had been too efficient.

Many of these people arrived in Berlin with nothing, their clothing ragged and torn. Just trying to obtain new clothing for them was quite a feat; there was a scarcity of practically everything in Berlin, including garments. International Jewish aid organizations such as HIAS and the American Joint Distribution Committee gave funding to the community center. They told us that Americans had joined together to give money to help us. Volunteers from America made themselves available to help the Jews who had survived the concentration camps.

I would return home to the Kusitzkys after each visit to the community center. As we ate dinner, they would always ask: “Have you found anything? Have you heard anything?”

But the answer was always no.

The people I met at the community center, for the most part, were of a stoic bent. Displays of emotion were minimal and there was little in the way of crying or weeping. The events that most of us had lived through had hardened us, forming a tough outer shell that seemed to isolate us and deny us the ability to grieve in a normal fashion. For many, there were no tears left to shed. Some were too overwhelmed by the magnitude of their losses and by the horrors they had witnessed to be able to weep freely. It seemed as if there were something in the human spirit that allowed most of them to endure only so much of the Nazi cruelties before, like an overloaded circuit, they shut down and became unable to feel.

But in spite of the numbness that seemed to have overcome me, some of the tales told by these concentration camp survivors still had the power to amaze. Their stories were so appalling, so beyond belief, that it was almost impossible for an ordinary person to grasp. These people assured me, time and time again, that they were not inventing their descriptions of the camps, as if they doubted their own memories. They named the camps death factories, whose purpose was to kill the maximum number of Jews as fast as possible.

One man I met had been a laborer at Auschwitz. His name was Paul Lewinsky, and he was deported with his parents in 1942, eventually winding up there, where he was forcibly separated from his parents. His parents were killed, but Paul, being tall and muscular, was assigned to work details.

Paul outlined for us how Jews were treated at Auschwitz. Those who were condemned to die were transported by railway car to the vicinity of the doors of the gas chambers. After leaving the cars, they were led through doors marked SHOWER, directly into a large, underground undressing area. They were told to undress for a bath and decontamination. To maintain the illusion, there were dummy showerheads and numbered pegs on which clothes could be hung, to be reclaimed after the showers.

Completely naked, the Jews were urged into the actual gas chambers. Any who resisted were beaten with rifle butts until they moved forward. The doors were closed and locked and the gas called Zyklon B was piped into the chambers. The screams and wails of the prisoners could be heard outside until, in a matter of minutes, all sign of human activity ceased. The work detail assigned to the showers would then open the doors and corpses would spill out, falling like broken dolls onto the ground outside. A team of dentists searched the mouths of the victims to remove any gold fillings, and the bodies of the women were examined to see if any valuables were concealed in their private parts. The heads of the women would also be shaved and their hair placed into bags for industrial uses.

Paul was one of the prisoners assigned to load the bodies onto wagons. Other prisoners would take the wagons to the camp ovens, where the bodies would be burned. Paul told me that they would periodically replace the prisoners who did this, killing the original laborers as they became unable to face the work and substituting new ones. He had been given his job toward the end of the operation of Auschwitz and was lucky enough to survive until the camp was liberated by the Russian Red Army.

There were three camps that, taken together, made up the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex. These camps were operated with factory-like efficiency. “Production” records were kept, documenting the number of Jews killed per day. The average was around two thousand gassed and burned in twenty-four hours, but a figure of almost nine thousand had been reached during periods of overcrowding or under other special circumstances. Estimates based on records left behind by the SS indicate around 1,100,000 Jews were killed this way.

Nothing was wasted by the Nazis, other than the lives of the prisoners themselves. Before his job loading the bodies, Paul had worked disposing of the clothing of the people who arrived there. Any valuables were confiscated. Paul had another skill that helped him survive. He was a silversmith. When the Nazis dug gold fillings out of the teeth of executed prisoners, he would use them to fashion jewelry and trinkets for the camp commandant and his cronies. The sheer volume of gold fillings, along with the prisoners’ jewelry and religious articles, made the profession of silversmith one much needed by the commandant.

Paul was also ordered to melt down gold articles, taken from the Jews, into gold bullion. Ingots of gold were shipped to Berlin, presumably to be turned over to the Reichsbank, the German state bank. So great was the quantity of pilfered gold that Paul eventually required four assistants to keep up with the demand for recasting.

Rings plundered from Jewish prisoners by the Nazis. Courtesy of USHMM Photo Archives

The frantic rate at which prisoners were killed did not lessen until Russian armies approached Germany. In late November 1944, the destruction of the Auschwitz facilities was ordered by Himmler, commander of all German SS and police forces. The SS did attempt to destroy the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex, but because of the rapid approach of the Russian Red Army, they only partially succeeded. When it became obvious that the Russians would overrun the camps before the job could be completed, the SS forced the remaining Jews to walk, in the dead of winter, toward and into Germany.

This herding of prisoners into Germany became known as the death march. People died from starvation and malnutrition. Many perished because they had no shoes. Lack of shoes was a death sentence; bare feet were cut and torn by rocks and debris until they became so badly mangled that walking was impossible.

If a prisoner couldn’t walk, he was useless to the SS and death was certain. When Jews died during a march, the SS unceremoniously dumped their bodies on the side of the road. In some camps, such as Auschwitz, Russian soldiers arrived to find the SS already fled, leaving the prisoners to themselves. Battle-hardened though they were, they were shocked to find about seven thousand skeletal, emaciated Jews, many dead and the rest not far from it.

Hardened though I was, when Paul told me all this, I was almost overcome. The thought of this legion of madmen murdering my friends and family, desecrating their bodies while claiming to be civilized members of a “Master Race,” was too much. In my mind, I pictured them digging the gold fillings out from the corpses of my kin, and then going home to dinner. Waves of nausea washed over me and I felt as if I might go insane when I thought that my parents might have suffered just such a fate.

But for an ordinary man to ponder too closely the workings of fate is a dangerous business, as was demonstrated to me the next day when I returned to the Kusitzkys. A stranger sat at the kitchen table. She was small of frame, with long black hair that fell over her shoulders. She looked to be in her fifties with a wrinkled forehead and creases that lined a smiling face. Despite the smiles, marks of long experience and deep pain could be readily seen.

Before I could say anything, Anni called out, “Dago! This is your aunt!”

Nothing Anni could have said would have surprised me more. I had not had the slightest expectation of anyone, least of all a relative, coming to find me. I just stood there, completely flabbergasted. Before I could gather my wits, she rose from her chair and came over to embrace me. She hugged and kissed me, muttering endearments.

From that moment on, I was no longer alone. We started talking and did not stop until the next morning. She was my aunt Riva Gutman, my father’s little sister from Kovno, in Lithuania.

She told me that she had met me as a little boy in Kovno when my mother and I visited there. The night wore on, as we talked about the family, nieces and nephews, aunts and uncles, parents and grandparents. I still couldn’t get over the fact that she had somehow managed to find me.

Riva had gone to the community center in hopes of locating my parents and discovered that I had registered there. After persuading the staff to give her my address, she walked all the way to Lübars. She had not expected me to survive the war and was surprised to discover that I still lived.

She had come to Berlin by train from the city of Lodz in Poland. Riva was aware that foodstuffs were in very short supply and commanded high prices in Berlin. In Poland, food was available in abundance and was relatively cheap. So she loaded up a large knapsack with items such as butter and salami and took the train to Berlin. The demand for food was so great in postwar Berlin that she sold everything she had within a few steps of the railroad station.

Riva wanted to accumulate enough money to pay her way to Palestine. This was her goal, and the goal of many other refugees. But not me, at least not yet. I wasn’t thinking about emigration. I was too preoccupied worrying about my parents and about Ilse and Klaus. But Aunt Riva talked ceaselessly about joining her in her quest.

My Aunt Riva and I.

“Come with me, Dago. Come to Palestine,” she would say. But I would refuse, not wanting to give up hope that my parents survived.

When the subject of her own family came up, she seemed reluctant to say anything. It was obvious to me that something sad had happened. Seeing her reluctance to talk about it, I didn’t push her. But eventually, with some gentle coaxing and many tears, she told me about her loss.

Riva had been forcibly confined with her husband, Meier Gutman, and her two children, Emanuel and Basia, in the Kovno ghetto. This was roughly one-quarter of the city that had been partitioned off to contain the Jewish population. Jews were not allowed to live in any other area. They were compelled to remain in the ghetto until moved by the Germans, to be relocated to labor camps in Poland, Estonia, and Latvia. These people were told that they would be well treated and would be employed as valuable workers in industries vital to the German war effort. That was the propaganda, intended to keep the Jews calm and to forestall resistance.

Eventually, the Gutman family’s turn for relocation came. German military trucks drove into the ghetto and soldiers were assigned to help the crowds find seats on the trucks. As Riva’s children were waiting their turn to climb into the trucks, a Lithuanian SS soldier took her little daughter, Basia, grabbed her legs, and swung her head against the truck. One look at the wound in her head left no doubt that she was dead. The SS man casually threw her body into a ditch in the side of the road. Riva saw it all.

The Lithuanian SS were said by some to be even more brutal than their German counterparts. They considered small children to be of no practical value to the Nazi war effort, and these children were often the first to be slaughtered.

Riva couldn’t stop crying for a long time, recounting that particular event. Nor could I.

Following the murder of her daughter, Riva, her husband, and her son were sent first to a labor camp in Estonia and then to the Stutthof concentration camp, near Danzig, Poland. At Stutthof, Meier, Emanuel, and several others attempted to escape. They made it past the gates but had only an hour or two to enjoy their freedom. They were quickly recaptured and brought back to the camp, where the rest of the prisoners were assembled and forced to watch as they were executed.

Riva remained in Stutthof until the end of the war, used by the Germans for heavy labor. She suffered terribly, carrying out assignments that, under normal circumstances, would have been far beyond her capacity for physical labor. But it was succeed or die. When she flagged, she was beaten. Had she failed completely to carry out her assignments, she would have been executed.

When the Russian Red Army approached Stutthof, Riva and any other Jews who had survived to this point were forced by the SS to march toward Berlin. Again, she somehow managed to survive while others died.

By this time, a large part of the night had slipped away, and Riva had to return to Berlin the next day. She implored me to go back with her, urging me to accompany her to Palestine, but I refused. My desire to find my parents outweighed all other considerations. If I left Berlin, the chances that my parents would find me would be almost nil. The next morning, I accompanied Riva to the train station, where we said our good-byes. She planned to make at least one more trip to Berlin to earn additional passage money, and we would meet again when she returned.

About three weeks later, she came once more to the Kusitzkys. I felt something special with Riva. Although some things were hard for me to discuss, I held nothing back from her. There were no secrets that I could not reveal to her. I told her all about my experiences during my time as a U-boat, about Ilse and Klaus, the Gestapo prison, and all the rest. I told her everything. In return, she would talk about the Kovno ghetto and the camps. Somewhere along the line, we became very good friends, and when the day had passed, it seemed much too short. The time had come for her to return to Lodz.

At the station, she again tried to persuade me to return with her. Again, I refused. I still had hope. Riva left for Lodz, telling me that she would come back one last time. She hoped that, if by then I hadn’t heard anything of my parents or Ilse, I would leave Berlin and come with her.

During those next few weeks, I continued to talk to people. I followed some leads, but they all ended up going nowhere. The Kusitzkys fed and housed me and gave me some of Heinz’s old clothes. At long last I was able to shed the rags that I had worn since becoming a U-boat. The community center also helped, giving me a little money, which I used to take the train to and from Lübars.

Eventually, Riva returned to Berlin. We talked once more about emigrating to Palestine. It had been quite a while since I first started looking for my parents. Riva told me bluntly that there was little chance that I would find my parents if it hadn’t happened by now. She forced me to make a decision I had been trying to avoid. By now, I had nearly given up hope. Although I felt as if I were being torn in two, I could not help but go along with her. My parents weren’t coming back, and my future was not in Germany, the country that had taken everything from me that I had ever cared about. I agreed to go with her to Lodz.

I left Riva’s Lodz address at the Jewish community center and prepared myself for a task I dreaded. Saying good-bye to the Kusitzkys was going to be difficult. They had given me food and shelter for quite a while, often at considerable risk to themselves. In some ways they had become the parents I no longer had, and I the son they had always wished for. Since everything of importance always took place in the kitchen, this is where I chose to make my good-byes.

“Stay here,” Anni and Alex pleaded.

But I could not. Germany was part of my past, not of my future. I tried to explain that Berlin held too many bad memories for me to remain. I intended to make a new start in a new country. For me, that country would be Palestine.

Anni cried, “Stay with us until you establish yourself. We will help you. There is no need to go elsewhere. Things will be so much better from now on! You will see. Stay with us!”

Though it almost broke my heart, I had to say no.

She continued trying to persuade me. “How can you go to a country whose language you do not know? To a place you know nothing about? It will be too difficult.”

I admitted the truth of what she said but told her that I still had to go.

They finally accepted my decision. Anni prepared a final packet of sandwiches for Riva and myself, and we departed the Kusitzky house. As we walked down the hill, I turned my head for a final look at the life I was leaving behind. Alex and Anni had been my shelter and comfort and I probably would not have survived without them. But I was twenty-two, the war was over, and the future beckoned. It was time to start a new life.