Part Two

ESTEBAN

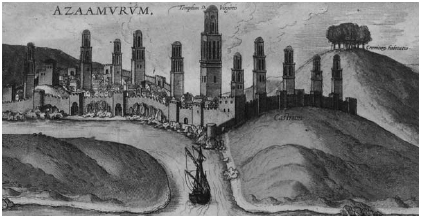

Azemmour, from Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg, Civitates orbis terrarum (1572). (Courtesy of the Jewish National and University Library, Shapell Family Digitalization Project and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Department of Geography, Historic Cities Project)

5

“NEGRO ALÁRABE”

WHO WAS ESTEBAN? Where did he come from? What was his background? How was he raised? What youthful experiences formed him?

It is impossible to answer these questions with precision because Esteban was an African slave. He almost certainly came from one of the west African kingdoms to the south of the Sahara desert, but no birth certificate exists; no entry in the parish register has survived. We know that he lived for a time at Azemmour, today a small, unimportant town on the Atlantic coast of Morocco, but there is no documentary record of his life there to tell us what he did or even who his owners were.

The fact that we have little concrete information about Esteban’s youth makes him emblematic of the wider African-American experience. The modern social concept of an African-American assumes ancestry in Africa and a story in which the point of origin, the seminal event, is the export of millions of slaves to America by Europeans. But the idea of calling those slaves “Africans” was originally European. The slaves themselves would have seen their origins in terms of their family, tribe, or clan, and in the principalities and kingdoms with which they identified. They thought of themselves as Wolof, Mandinga, or Songhai; they were from Guinea or Mali. They had no concept of being “African”; nor would they have regarded themselves as “black” until they reached the European world.

For modern African-Americans, the intervening centuries of marriage and shared experience mean that precise African origins have become obscured and often uncertain. African-American history is colonial and American, underpinned by an imprecise sense of a prehistory in which Africa is an ill-defined, at times almost mythical place of origin. In the same way, Esteban’s African story is obscure, and our sense of his historical identity begins when he reaches America and takes on a role in the Spanish colonial world. He is not the first African-American simply in a practical sense, but also symbolically.

However, although there is poetry in dwelling on the obscurity of Esteban’s origins, it is possible to throw some light on what his early life must have been like. To do that, it is best to begin with the most specific evidence available. We know that Shipwrecks described Esteban as a negro alárabe, natural de Azamor, “an Arabized black, native to Azemmour.” The apparently simple Spanish phrase negro alárabe is profoundly emblematic of an important problem, which has obscured and confused our sense of Esteban’s origins and identity because, from time to time, historians and other commentators have suggested, against all the evidence, that Esteban was not really a black African at all.

To set the record straight and to understand why this is important, it is useful to repeat the essence of Richard Wright’s argument of 1902, quoted in the Introduction. Wright concluded that “the useful and noble deeds of the Negro companions of the Spanish conquerors” had not been properly recognized because historians tended to see the masters as being entitled to credit for the work of their slaves.

At the time, Wright was specifically concerned with the way the prolific late-nineteenth-century philosopher and historian John Fiske had represented Esteban in his wide-ranging two-volume history, The Discovery of America, published in 1892. Fiske’s reputation has always been considered tainted by his racism and theories of Anglo-Saxon superiority. He had thoroughly irritated Wright by playing down Esteban’s role in the “discovery” of New Mexico and Arizona and referring to him as “poor silly little Steve.”

Wright himself had been born into slavery, but after exemplary military service in the Spanish-American War, he became an energetic supporter of African-Americans’ rights and was highly influential politically. He rounded on Fiske, determined to show that New Mexico and Arizona had been “discovered” by a “Negro,” and not by Esteban’s companion Marcos de Niza. Using the cunning of a lawyer and the precision of a scholar to artfully repackage Fiske’s words to suit his own purpose, Wright wrote:

Indeed it seems clear that a fair interpretation of the facts related in Dr. Fiske’s work would warrant the conclusion that [and here Wright quoted Fiske himself ] “a man [Esteban] who visited and sent back reports of a country,” is more entitled to the honor of its actual discovery than [Marcos de Niza] who, according to Dr. Fiske’s own statement, “from a hill, only got a Pisgah’s sight of the glories of the country, and then returned with all possible haste”—without having set foot actually within the Cibolan settlements of New Mexico.

Wright was careful not to accuse Fiske or any other historian of overt racism, but instead argued that black Africans had not been properly represented because history was a product of a hierarchical society. His argument was not with the institution of history itself, but with the racial prejudices that continued to influence the perspectives of historians.

In 1940, another distinguished African-American scholar, Rayford Logan, argued in the new academic journal Phylon that overt racism and prejudice of individual historians had led Esteban to be incorrectly described as a North African “Moor,” rather than as a “Negro,” and had denied his “discovery” of New Mexico and Arizona. Logan wanted to set the record straight and establish once and for all that Esteban was a “Negro” and had been the first non-Indian “discoverer of the southwest.” He set about that task in the light of his own experience of racism in America, and accordingly he was interested not simply in the truth about Esteban, but also in how that truth had been suppressed.

At the time Logan was writing, the American southwest was celebrating the 400th anniversary of the “discovery” of New Mexico by Francisco Vázquez de Coronado. In 1540, Coronado had presided over a sanguinary sojourn into Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Texas, and beyond. It was a venture frequently punctuated by bloody brutality perpetrated against largely friendly Indians. In the first place, Logan, like Major Wright, wanted to make it clear that, however you interpreted the historical documents, one thing was certain: Esteban had “discovered” New Mexico before Coronado and was quite possibly its “sole discoverer.” And he clearly believed that racism was one reason why “the Southwest chose to commemorate in summer-long fiestas the entrada of Corando” instead of Esteban.

Logan was also troubled by the fact that those in charge of the celebrations “had made Estevanico a Moor rather than a Negro.” In this Logan erred somewhat, for most of the publications produced as part of the commemorative festivities refer to Esteban as a “Negro.” The notable exception was an essay by Cleve Hallenbeck, a meteorologist, whose hobby was the history of the southwest. He claimed that Cabeza de Vaca’s “plain statement that [Esteban] was an Arab leaves no room for argument.” This assertion was based on his interpretation of the phrase negro alárabe, natural de Azamor; and it is an assertion that, when I first read it, seemed to me to be totally wrong.

So I turned to a respected authority on the Spanish language, a former teacher of mine, Professor John Butt, who explained that negro should be translated as “black man” and alárabe as “Arabic-speaking,” or perhaps “Arabized.” Whoever wrote these words meant that Esteban was a black man who was, in some way that is left unspecified, culturally but not racially Arab. It certainly does not mean a black Arab, a Moor, a Berber, or any other race usually associated with North Africa. Esteban was almost certainly Negroid and of sub-Saharan ancestry.

But as I read more, I found that Hallenbeck’s ignorance of Spanish had not deterred him from further inaccurate explanations of why he thought Esteban was a Moor or an Arab. He also noted that one Spanish conquistador who had met Esteban referred to him as moreno, “brown”—not black. Hallenbeck obviously had no idea that Spaniards used the phrase los hermanos morenos to refer to a Christian brotherhood that was founded in Seville specifically to provide social and spiritual support to black slaves and freedmen of sub-Saharan origin, a Christian brotherhood popularly known as Los Negritos, even to this day.

Given Hallenbeck’s breathtaking arrogance when it came to holding forth on the niceties of the Spanish language, it is hardly surprising that he also informed his readers that in Cabeza de Vaca’s time, Spaniards applied the word negro to “people of Hamitic and Malayan blood as well as to Negroes.” Of course, he was in no way qualified to make such an assertion, but on this occasion he was not entirely mistaken. He was simply wrong about how the word negro was used and what it meant.

Rayford Logan had himself pointed out that the Spanish sources nearly always refer to Esteban as el negro, “the black,” and that nearly all translators had interpreted this as meaning “Negro.” He also realized that Cabeza de Vaca used the same word, negro, to describe the human cargo of a Portuguese slaving ship. But Logan never came to grips with the fact that Spaniards at that time did sometimes describe Arabs and Moors as negro. So what did sixteenth-century Spaniards really mean when they referred to a man as negro?

Negro is simply the Spanish word for “black,” and as such it was used to describe the color of objects and people’s moods. In that sense, it was no different from the meaning of the word “black” in English today. But Spaniards used the word negro about people in two ways: they might use it as an adjective to describe people’s skin color or even their character, whether they were Spanish, Moorish, or African; but when they talked of un negro, or una negra, “a black” (male or female), then they meant what Wright and Logan understood by the word “Negro.”

In the Middle Ages, all over Europe and the Mediterranean, from England in the north to the North African Muslim lands in the south, from Spain and Portugal in the west to the Ottoman empire in the east, the far-off, mysterious world beyond the Sahara Desert was known as the Land of the Blacks. What was meant by this is made obvious by a world map made in Catalonia in northeastern Spain in 1375, which shows the Kingdom of Melley (from which we get modern Mali), south of the Sahara Desert. The King of Melley is clearly shown with characteristic Negroid facial features and hair. Nearby, a short commentary explains who he is:

This Black Lord is called Musse Melley, Lord of the Blacks of Guinea. This King is the richest and the most noble Lord of all this area because of the abundance of gold found in his lands.

In fact, although the Catalan uses negre, “black,” to describe both ruler and subjects, the translation offered in a sumptuous edition produced in the 1970s describes the king as “this Moorish ruler…lord of the negroes of Guinea.” In other words, as late as 1978 negre was being translated as “Moor” when used of a king and “Negro” when used of a subject!

Nearby, to the west and in the desert, the map illustrates a man with a pinkish face, who is riding a camel, and has an encampment of tents pitched nearby. He is evidently intentionally portrayed as having a much lighter skin color and more Caucasian or Hamitic features than his “black” neighbor. He is probably a Tuareg, for the description tells us that “all this area is populated by people who muffle up so that one can only see their eyes. And they live in tents and ride camels.” It is clear from the contrast between this man and the “black” Musse Melley that the mapmaker wanted to show them as belonging to two different races.

Writers also made this distinction. In the 1450s an Italian merchant, Alvise (or Cadamosto), described his exploration of the west coast of Africa. He wrote about nigri and arabi, clearly distinguishing between blacks and Arabs. In exactly the same way, a Portuguese history written at the beginning of the 1500s differentiated between the mouros and negros of the Mandinga region. Near the end of the 1500s, a Spaniard described the five regions of Africa as Egypt-Ethiopia, Barbary, Numidia, the desert regions called the Sahara, and “the land of the negros” beyond the desert. Throughout the sixteenth century there was a sense that the negros were different from North Africans and were from beyond the desert.

In fact, the difference between Moors and negros cannot be explained more clearly than by looking at a grant made in 1594 by the King of Spain to his subjects in the Canary Islands. He gave them the right to raid North Africa for slaves, “because,” as the royal decree explained, “the alárabes [Arabs] of that land have many esclavos negros [black slaves] and moreover…there are other Moors who ransom themselves, paying with many negros [blacks].” So the reason for attacking Barbary North Africa was to capture or extort the black slaves belonging to the Arabs and Moors.

And the reason they wanted “black” slaves is made quite clear by a seventeenth-century Spanish lawyer, Cristóbal Suárez de Figueroa. “When it comes to talking about the slaves you can get today, well, they are either Turks and Berbers, or Blacks. Of these the first two kinds are usually untrustworthy, being great sinners and criminals. But the Blacks,” he said, “are much better natured.”

Here we may glimpse Esteban’s story, for he was probably once one of these black slaves owned by a North African Arabic-speaker. And it is clear that men like Esteban, who were from the sub-Saharan “land of the blacks,” were closely associated with slavery. But to better understand how negro was used in the specific context of slavery, it is helpful to look at Vicenta Cortés’s classic study of the Spanish slave trade for the forty-year period immediately before Esteban first arrived in Spain.

Cortés toiled for a decade or more in the Spanish archives, carefully reading the records of thousands of transactions made by dealers at the slave market in Valencia. No one could be better qualified to judge the meaning of negro (in this case the Valencia cognate negre). As one reads her book, it quickly becomes clear that her examination of the documents had revealed that there were two basic categories of slave: “white” and “black.”

The documents describe various origins for “white” slaves. Some are Moors; some are from Barbary; there are even a few Jews. Among these there is an occasional reference to blancos oscuros, “dark whites.” In other words, in these official documents and legal contracts, there was resistance to using the word negro or negre to describe white slaves. By contrast, most examples of negros that Cortés came across referred to men and women imported in large numbers by the Portuguese from their fortresses at Arguin, Cape Verde, San Jorge da Mina, and San Thomé, the engine rooms of the sub-Saharan trade.

But in these documents there are examples of apparent anomalies that seem particularly relevant to our discussion of Esteban’s origins. For there is at least one reference to a negra mora (Moorish black woman); elsewhere, there is one to a negro moro (Moorish black), who is later described as el negro (the black) in contrast to two moros (Moors) who had been captured at the same time. Many years later, Cortés explained that these “so-called Moorish blacks [were] converts to Islam, [whose] geographic place of origin [was not stated in the documents], which leads us to think that such examples refer to blacks who arrived from north African kingdoms, but [originally] came from further south.” Again, we glimpse something of Esteban’s origins alongside the negros moros, because these Moorish blacks seem to have also been “Arabized.” They too might have been referred to as negros alárabes, as Esteban was.

More recently, Aurelia Martín has researched this subject in the archives of Granada. As a result of many hours spent in the company of documents written in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, it became so obvious to her that negro in old Spanish was used to refer to black Africans of sub-Saharan origin that she coined the term negroafricano to cope with the problem of how to make the distinction in modern Spanish. That she had to do so reveals just how confusing it is to use colors in the description of races and, more controversially, also suggests the latent typological inadequacy of racial taxonomy in the modern world.

In fact, the word negro when applied to slaves clearly meant something other than “black” in the sense of color, just as “black” does today in modern English. This is obvious in the way negros were often described by sixteenth-century Spanish notaries as “light,” “dark,” or even “very dark.” This tells us that the people who wrote descriptions of slaves as part of their work thought of the word negro not as meaning the color black but as describing a “race” characterized by a range of skin colors.

The plain and simple truth is that this distinction between slaves who were negros, sub-Saharan Africans, and those who were blancos seems to be universally accepted by scholars of the specific subject of Spanish slavery. It seems that Rayford Logan was right to describe Esteban as a “Negro.” But scholars who study the history of slavery now generally agree that “race” itself does not exist in terms of biological difference and that the idea of “race” is therefore outmoded. The apparent differences between people, it is argued, are best understood in terms of social and cultural distinctions, not skin color or other physical characteristics. And so it is sensible to ask if we should really worry about whether Esteban was a “Negro,” a negroafricano, an Arab, or a Moor. After all, might it not be racist to make that distinction?

It is possible to avoid this problem by arguing that Esteban’s identity as an African-American is what is important, and that how African-Americans may be defined is not the business of this book. As long as the concept of an African-American is current and as long as African-American history is seen as beginning with enslavement in Africa, then Esteban is important because he is the first African-American. Arabs, Moors, and Berbers rarely enter into that story except as slavers and slave merchants—people who had bought and sold slaves from beyond the Sahara Desert long before the Portuguese, the Spanish, or the English. Arabs, Berbers, and Moors are not part of the African diaspora; they were part of the Mediterranean and European world that brought about the diaspora, even though a few may have ended up enslaved themselves. In fact, it is thought that as many sub-Saharans were forcibly removed from Africa along Islamic trade routes as were shipped to America by Europeans.

Esteban was born during a period in history when those who survived were all too often traumatized by life itself. It was an era that was not merely scarred by violence, disease, and famine but was also sickened by the exploitation of the poor by the powerful and fraught with war and conflict as Europeans raged over land and religion. It was a time when even Spanish noblemen, whose birthright was membership in the aristocracy, at the summit of that wealthy and expanding empire, suffered the horrors of their bellicose world. Indeed, fighting was in their blood and the empire itself as often as not brought strife to men like Cabeza de Vaca, Dorantes, and Castillo. For they came from a warrior class; men whose badges of honor were their trusty steeds and their weapons, and who, fuelled by pride and prejudice, fought for king and homeland on the frontiers of empire.

In a strange way, Esteban would become an “almost” member of that noble class of valiant, imperial flotsam as he and his companions negotiated their survival in Indian country, far beyond the boundaries of the known world. He too would share the life of a commissioned officer in Spain’s imperial venture, in his own way. He too would feel the cut and thrust of bloody butchery in a remote foreign land, fighting for a sovereign he had never seen.

Studies of the Spanish slave trade show that it was usual for a slave to be described in official documents as being from the place where he or she first became the property of a European slave merchant. So, as Esteban was described as a natural de Azamor, a native of Azemmour, we can assume that he was sold into captivity there. But the history of Azemmour makes it likely that he was from farther south, beyond the desert, from the Land of the Blacks.