Part Five

THE SEVEN CITIES OF GOLD

1536–1539

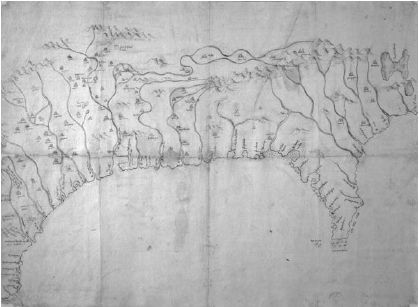

The Gulf of Mexico (c. 1544). This slightly later map shows the River and Bay of the Holy Spirit and the “Bahía Honda” (Tampa Bay, the Deep Bay) on the gulf coast of modern Florida. (Courtsey of Archivo General de Indias; MP México 1)

IN PART ONE, we traced the survivors’ journey from north of Culiacán, in the far northwest of Mexico. We saw them meet the Spanish slavers and Melchior Díaz, before traveling on to Guadalajara and the viceregal capital, Mexico City. There, they were royally treated by the viceroy, Antonio de Mendoza; and by the great conquistador Hernán Cortés. They also met the stern Archbishop, Juan de Zumárraga, who had his own plans. These mighty Mexican oligarchs tried to bribe and cajole the four survivors to ensure that the official report they made in the Audiencia served their own powerful interests.

Oviedo and Shipwrecks give the modern historian a good but imperfect idea of what went into that first official report made in the summer of 1536. But we also have a strong sense of the exaggerated and fantastical rumors that quickly developed as the four survivors embellished their own stories in private, in the taverns and at the dinner tables of Mexico City, telling their tale in the way that adventurers are prone to do. And it was not simply that the survivors told the tale again and again, but, then, again and again it was retold by others, changing, developing, and all the time becoming more fanciful. With each new telling another layer of fantasy further veiled the truth beneath.

During their long march across America, the survivors had learned about the large Indian towns on the upper Rio Grande from the Jumanos Indians of the area around Big Bend and the Junta de los Rios. These belonged to an archipelago of important settlements that made up the sophisticated Pueblo Indian culture, which thrived as far away as Zuni on the borders of New Mexico and Arizona and among the Hopi and beyond. The Pueblo Indians lived in well-defended urban centers with large honeycomb constructions of multiple stories, the low-rise apartment blocks of a bygone world. Their society embraced politics and civic administration.

The Pueblo Indians were far more sophisticated than their neighbors, hunter-gatherers like the Karankawa or the seminomadic Jumanos. So, when the Jumanos told the four survivors about large towns to the north, they described places that they thought of as great cities of almost unimaginable size. The four survivors themselves had been impressed by the relative sophistication of the tiny permanent settlements around Big Bend, after their brutally simple life on the Texas coast. The mysterious pueblos to the north thus became a symbol of civilization for Esteban, Castillo, Cabeza de Vaca, and Dorantes while they were living as Indians.

In reality, the pueblos were little bigger than villages, no more than simple sedentary communities compared with the advanced civilizations of Aztec Mexico, Inca Peru, or Spain. But in the minds of the four survivors they had become exaggerated, because they had offered some semblance of hope in a time of desperation.

The Spaniards of Mexico City were eager to believe those exaggerations. There was a simplistic logic to the belief that if the great Inca civilization had been discovered in Peru and Cortés had found the Aztec Empire in Mexico, then it stood to reason that a similarly golden prize lay somewhere in North America. It is worth remembering that when Cortés first set foot in the Aztec capital Mexico-Tenochtitlán, he told the Emperor Montezuma that the Spaniards suffered from a disease of the heart that might be cured only with gold.

That belief in a civilization in the north was encouraged by the medieval Spanish legend of the “Seven Portuguese Bishops,” who had fled from the advancing Moors during the bleakest period in the history of Christian Spain. During that Dark Age, the bishops took to their boats and sailed out into the Atlantic Ocean, until they eventually reached a great island, where they settled and founded seven Christian cities. This old legend was given a new lease of life in 1448, when sailors from a Portuguese ship claimed that a ferocious storm had driven them onto the shores of that legendary island. They said that they had been carried on the shoulders of the population to a church, where a Mass was said. Then, when the storm relented, they set sail and went home to Portugal, where they were severely scolded for failing to record the precise position of that miraculous Christian island.

North America was quickly identified in the collective imagination of Spanish Mexico as the island where the “Portuguese bishops” had established their colonies. That speculation was fueled by a story told to Nuño de Guzmán by a Tejos Indian, who reported that great civilizations lay to the north of Mexico. When he was a child, that Indian said, his merchant father had often traveled through the Pueblo country, trading his beautiful feathers for gold and silver, which were common metals in those parts. Once or twice he himself had gone too and he remembered visiting towns so large that they seemed comparable to those in Mexico. There were seven such cities, and each was home to a whole street of goldsmiths. The best way to reach those seven cities, the Indian went on, was by way of a grass-covered desert that lay between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean.

Long before the four survivors arrived in Mexico in 1536, the Spaniards had developed a varied but always hopeful geography of North America. In 1527, as Narváez prepared to set out for Florida, a Spaniard well experienced in the withering wonders of the New World had lampooned the ludicrous nature of Narváez’s enterprise. How, he had asked his sovereign, was one expedition to even explore, let alone conquer, the vast landmass of over 2,000 leagues that lay between Florida and the Pacific coast? But this critic, who at first seems quite sensible, later strongly advised that it would be better for Narváez to go in search of a city called Coluntapan, where the people wore silver armor and carried metal weapons. He too had fallen victim to the Spanish disease of hopeful delusion.

Spanish Mexico vibrated to the mesmerizing rhythm of such stories, which filled raconteurs and audiences alike with hopes and desires for future adventures. In 1536 and 1537, Esteban, Castillo, Cabeza de Vaca, and Dorantes sowed the seeds of a more focused covetousness on this very fertile ground and greed suddenly gripped Mexico, taking control of the collective colonial mind. The survivors told a story that easily mingled exaggerated fact with outright fiction. And as dreams turned into belief and belief took on the certainty of faith, the road to the Seven Cities of Gold came to be revered by many a conquistador as a certain path to wealth.

By contrast with the many hopeful dreamers, Mendoza, Cortés, Zumárraga, and the four survivors were pragmatists who must have guessed that rumors of the Seven Cities of Gold were simply a myth. But they also understood that such dreams and hopes were a spur to action. The Seven Cities were a metaphor for an intangible prize, a symbolic goal; but these practical men all recognized that a very real, very tangible prize was at stake in North America. The four survivors had described a “land of cows” and had explained in private that the Indians talked of a great grassy sea, endless fields where enormous herds of wild cattle roamed free. They had heard about the Great Plains. That was the news which excited Mendoza, for he had arrived in Mexico with clear instructions from the Crown to develop stock raising in the colony.

The richest and most powerful institution in Spain, after the Church and the Crown, was the Mesta, which controlled sheep farming and the wool trade. In 1537, as Mendoza and Zumárraga wrangled over the right to organize an expedition to the Seven Cities, the viceroy established the cattle breeders’ association of Mexico and called it the Mesta too. The four survivors’ reports of vast herds of cattle ranging on boundless grazing land were much less romantic than the thrilling news about cities filled with streets of goldsmiths that excited impoverished and quixotic conquistadors, but any rich Spanish aristocrat knew that stock was a surer path to wealth and power.

BY THE LATE summer of 1536, the four survivors had given their formal testimony and were able to relax and begin to plan their futures. Shipwrecks reports that as soon as they had finished with the official account, Cabeza de Vaca decided to seek a personal audience with Charles V. He set out in October for the port of Veracruz, but a storm destroyed his ship before he could embark, and he went back to Mexico City.

Over the winter of 1536 to 1537, Mendoza time and again discussed a possible expedition to Cíbola with the survivors. Meanwhile, Cortés tried to persuade the viceroy’s right-hand man, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, to lead an expedition into the lands to the north. But Mendoza was firm in his response. “You know only too well,” he told Coronado, “for you know the kind of man I am, that I will never accept any such proposition from Cortés or anyone else other than His Majesty, nor would it be right to do so.” Mendoza concluded by informing Coronado that as soon as he was given permission to do so by Charles V, he would personally underwrite the expedition himself. “Never again speak to me of this matter!” Mendoza commanded. The viceroy, Cortés, and Zumárraga all hoped to persuade the four survivors to guide an expedition into those rich northern lands.

But the Mexican oligarchs were to be disappointed. In February of the following year, 1537, the viceroy had to write to the Spanish Crown with the news that both Dorantes and Cabeza de Vaca would soon come to Spain to give an account of their adventures in person. There was little chance now that an expedition to Cíbola would be led by one of the senior captains who had survived the Narváez expedition.

Mendoza must have then considered Alonso del Castillo but for some reason seems to have discounted him as a possible candidate. And although no explanation for this is offered by the contemporary documents, we can hazard a guess.

We know Castillo was very young at the time he went to Florida, for, in 1547, when giving legal testimony in Mexico City, he gave his age as “35 years or more.” During that period in history, few individuals knew precisely how old they were, and dates are often imprecise in this kind of document, so he may have been as old as forty or even a year or two older. Even so, Castillo would therefore have been between fifteen and twenty-one when he set out with Narváez. By the time he reached Mexico City in the summer of 1536, he had spent well over half his adult life as an Indian. He must inevitably have seemed somewhat weird if not actually mad. Mendoza perhaps felt that Castillo was mentally unstable and therefore an unreliable military leader. Instead, Mendoza arranged for Castillo to marry a wealthy widow, and he settled down for a while. Within a few years he had established a family home in the town of Puebla de los Angeles, where his wife was a landowner.

That left only one man as the possible leader for the proposed expedition. Mendoza wrote to Charles V and explained that he had “bought a black slave from Dorantes,” a man called Esteban who would make a good guide for the expedition because “he had been to those lands” and “was a civilized, intelligent person.”

There is some doubt as to whether Mendoza actually bought Esteban or whether he remained Dorantes’s property. A Spanish chronicler called Baltasar Obregón reported that Andrés Dorantes was “noticeably upset” at the prospect of having to sell Esteban to the viceroy. “He would not sell Esteban,” even “for 500 pesos,” which Mendoza sent him “on a silver platter.” The average price for a slave during that period was between 100 and 150 pesos, so the offer was not excessively generous if we take into account Esteban’s priceless knowledge of the north. Not surprisingly, Dorantes seems to have refused. But to defy a man as powerful as Mendoza was dangerous. If pushed, the viceroy could invent some legal ruse and “steal” Esteban without much trouble. So Dorantes had to offer some kind of deal. Obregón reported that he then agreed to hand over Esteban to the expedition without charge for “the good of His Majesty” and to help save the souls of the many “natives of those provinces.”

The touching description of Dorantes as “noticeably upset” at the prospect of being parted from Esteban has led some to draw a sentimental picture of the relationship between master and slave. The good Dorantes is thus pictured as effectively giving Esteban his freedom so that he could join Mendoza’s enterprise. But the reality was surely more prosaic. As long as Esteban remained his property, Dorantes could stake his own claim to any riches his slave might discover: precisely the point made, in the context of writing history, by Richard Wright. There may have been a strong emotional bond between the two men after their years together in the wilderness, but Dorantes’s reported refusal to sell Esteban to Mendoza was at least in part a commercial decision.

However, while Cabeza de Vaca reached Spain in the summer of 1537, Dorantes spent ten months lost at sea on a ship captained by the criminally unscrupulous Sancho de Piniga, as explained in Chapter 10. When he finally returned to Mexico, late in the year, Mendoza immediately offered him command of the expedition to the Seven Cities. But Zumárraga then forced Mendoza’s hand, insisting that there should be no Spanish military expedition. Instead, Marcos de Niza was put in charge and Esteban was appointed as his guide and given the command of an army of Indian companions.

Mendoza can have only guessed at what kind of man Esteban might turn out to be, for he could have had no idea how such a unique cultural hybrid might react to being given official responsibility. But one thing was certain: Esteban would never be able to claim any conquest as his own in a Spanish law court. At times the viceroy must have wondered whether this marvelous African was perhaps as dangerous a choice as Castillo might have been. Esteban was an alien child educated by dislocation, a man who had learned the lessons of violence and the whims of the Fates. He was the supplicant of many gods and high priest of a few. In truth, Esteban himself was perhaps far from certain how he would behave when faced with the Indian world once more. His identity was always subject to change and the vagaries of destiny; he was a postmodern man in an early modern world, an inhabitant of the global village before its foundations had been dug. Even now, Esteban was coming to terms with yet another unique experience, the surreal world of Mexico City.

He now found himself in an extraordinary position, almost certainly unique in the African experience of the early Spanish-American Empire. He was still a slave, but he was also a celebrity, almost like a Roman gladiator, part actor, part mercenary. He was the viceroy’s houseguest and always in demand at the dinner tables of the most powerful men in Mexico. He must at times have felt as though he had becoming a living version of the Indian legend of El Dorado, the “gilded man” who was painted with gold every morning by his servants. He had something of a living myth about him.

One would-be biographer has suggested Esteban now threw himself wholeheartedly into the “good life” of Mexico City. “A lover of women,” he made the most of this opportunity and “gave free rein” to his desires. “Like all those of his race, he wore brightly colored clothes when he sauntered through the city streets,” all the better to play the part of Don Juan. “For it seems he had a great weakness for seducing young Indian girls who were no doubt attracted by such an exotic figure.”

The racial stereotyping in this commentary overshadows an otherwise plausible portrait, for showy attire, amiable drinking, and casual whoring were the regular pastimes in Mexico City of many a leisured soldier who had won his spurs and his gold and who waited unhurriedly for the next call to arms. Such are the ways of men on the frontiers of empire. Esteban was an exception among the African population of Mexico in the 1530s, but he was a celebrated adventurer perhaps quite happy to share the easy life of his Spanish peers. Equally, we would do well not overemphasize the importance of the two brief Spanish reports of his promiscuous ways.

THERE HAS LONG persisted a romanticized picture of the lives led by the first black slaves brought across the Atlantic by the Spaniards. These pioneer African-Americans were treated more as domestic servants than as slaves and were protected by medieval Spanish laws—so the story goes. This inaccurate image is useful because it clearly contrasts the conditions experienced by men like Esteban with the industrial scale of the southern and Caribbean plantations, which we usually associate with slavery in America.

But that romantic notion of some happy harmony between servant and master is a fiction. From the outset, the Spanish colonies in the New World suffered from a chronic shortage of labor. The Spaniards soon discovered that the Indians did not adapt well to the politics and practicalities of peasantry and serfdom. Their world had been free of feudal suffrage and universal villeiny and they made unproductive serfs who became depressed and indolent in the face of forced labor. Worse, their numbers were falling alarmingly as the disruption to their society led to a reduced birthrate and Old World diseases decimated those who were born.

The problem was exacerbated by the fact that the Spaniards who sailed for the New World arrived with haughty pretensions to nobility and they refused to work with their hands and would not till the land. Spain found a solution in 1501, when it was decreed that Christian blacks, known as ladinos, or “latinized” Africans, should be sent to the colonies to provide the necessary manual labor for farming and mining.

Year after year, there was fierce discussion of this policy. There were those on the one hand who claimed that these ladinos were well suited to colonial life because they had been latinized and taught European, Christian ways. But others believed that precisely because ladino Africans had been “civilized,” they had learned to respect themselves as rational men and therefore abhorred their slavery and tended to rebel against their condition, much as a Spaniard might if he were enslaved. Astonishingly, it is an argument that survived in respected historical works well into the twentieth century. There were many who argued, on these grounds, that it would be better to import slaves directly from Africa because they had no experience of European society and culture. Such slaves were known as bozales.

The reality was more pragmatic. The colonists needed manpower, and the most productive laborers were Africans. As the colonies grew, there were not enough ladinos to go around. The argument that bozales were more docile and the ladinos more troublesome was largely a convenient way to combat the religious moralists who were worried that slaves brought straight out of Africa might corrupt the Indians with their pagan religions.

In 1518, on the eve of Cortés’s conquest of Mexico, that moralizing religious debate about ladinos and bozales was sidelined by Charles V. In order to raise funds for his own political campaigns, he sold a license for the export of 4,000 African slaves to the Americas. It was the first of many issued to raise funds for the Spanish Crown.

Africans quickly became as much a feature of Spanish colonial life as the Spaniards themselves. Some served their masters as pampered popinjays, manikins for the display of private wealth, to be sure, and many were certainly domestic servants. But every mule train that traversed the Mexican landscape carrying trade goods seems to have had its black teamsters. Thousands of blacks were employed as overseers in textile mills or as stewards on the conquistadors’ great estates, slaves whose task was to force labor and tribute out of the subject Indians. Many others labored themselves on the land or in the mills. The lot of Africans in the Spanish New World was diverse.

Slowly, the number of free blacks grew and enough achieved sufficient prosperity for the Spanish Crown to determine, in 1574, that they should be accorded the civic privilege of becoming taxpayers. A royal decree explained that the Crown had heard that because of the great natural wealth of the Indies many black and mulatto slaves were now free and relatively well off. As they were now royal subjects, just like the Indians, these free blacks should now be expected to pay an annual tribute of a silver mark. Clearly, a peacefully settled population of free blacks was expanding in rural Mexico. But, however peaceful, they proved to be uncooperative taxpayers who steadfastly resisted attempts to extract the tribute now due to the Crown. Perhaps it is more surprising to learn that enslaved Africans also managed to own property, although the Crown tried, unsuccessfully, to prevent them from doing so, and also failed to tax them on it.

Africans frequently appear in legal documents as the agents of their Spanish masters in the criminal exploitation of the Indians. They forced their way into Indian homes, stole their wares from them as they prepared to go to market, and organized press-gangs to round up Indian men when there was hard work to be done. No doubt encouraged by their experience of such exploitation in the service of the Spaniards, it seems that many Africans oppressed Indians from time to time for their own benefit. In 1541, the Spanish authorities in Peru complained that black slaves were out of control and went about stealing all that they could from the Indians and even “retained many male and female Indians as servants,” all of which was quite “ruinous.” Irony, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder.

The Spanish government reacted to these problems with the usual recourse to grim punishments and by authorizing the Indian authorities to arrest Africans who marauded among the Indians. But they also resorted to a principle of local apartheid that tried to prevent blacks from living in Indian communities at all.

In practice, attempts to separate Indians and Africans proved futile, not least because many more African men than women were exported to the New World. And so, just as Spaniards took Indian women as wives, mistresses, lovers, and concubines, so too did African slaves.

The Spaniards were horrified by any union between Africans and Native Americans and by the cross-fertilization of the two cultures and societies. There were many deep-seated psychological reasons for their horror, which were often manifested as a fundamentalist fear of African and Indian religions. The religious authorities were especially concerned because African and Indian curanderos, medicine men and women, adopted rituals and practices from one another and then incorporated aspects of Christianity as well. It was a richly heterodox alchemy that frightened the Church and fueled the zeal of the Inquisition.

Esteban must have been very worried, for he and his companions had survived their long ordeal among the Indians of the north thanks to his ability to combine African and American animism with Christian spirituality. Like his aristocratic Spanish companions, Esteban had every reason to fear the Inquisition.

But while the religious authorities were concerned about such heterodoxy, all Spaniards in Mexico were utterly terrified by the prospect of rebellion. They were not simply paranoid about a slave rebellion in the way that slave owners have been throughout history: in Mexico those fears were exacerbated by the possibility that the African slaves might unite with the free Indian population. There is every reason to believe that paranoia was well founded. Slaves and Indians had every reason to rebel, and they far outnumbered the Spaniards.

In the summer of 1537 that terror exploded into violence, and Esteban saw firsthand the extreme extent of man’s unbridled capacity for cruelty to his fellow man.

BY 1537, THERE were as many Africans as Spaniards living in the Spanish district, the traza, at the heart of Mexico City. But they were a people apart. The oppression of African slaves on the grounds of geography and skin color led members of African tribes and nations who had treated each other as different and even as enemies when in Africa to regard themselves as unified by Spanish racial oppression. They began to experience a sense of a new and collective identity as Africans that was based on slavery, that was utterly colonial, and which led to a sense of themselves that was uniquely American.

News had arrived in Mexico, in 1535, of a fundamental change in the human rights extended to Africans and Indians by the Spanish Crown. The Crown had decreed that there was too much delay in the sentencing of serious criminals and revoked the long-standing right of all negros, freedmen as well as slaves, and Indians to appeal to the high court in Spain in cases where they had been sentenced to death or to corporal punishments such as having limbs or testicles cut off. The latter was a not infrequent punishment meted out to runaway slaves. This must have seemed like a sensible and pragmatic move to prevent endless dissembling by convicts, but in practice it handed too much power to the colonial officials, who were also the slave owners. Far from being an administratively expedient move, it aggravated Africans’ antagonism toward the ruling elite. Crucially, it alienated free blacks by sending a clear message that they were still considered “almost slaves.”

In such a climate, the Spaniards’ paranoia escalated. On the night of September 24, 1537, after a long, stifling summer, Mendoza was working late on the usual business of the colony. An African turncoat, probably a free man who felt himself more conquistador than negro, came to Mendoza with the news that the Africans had chosen a “king” and were plotting to rise up and seize the land. “Because my informer was black himself,” Mendoza reported to his sovereign, “I did not believe him.” But because he had also told the viceroy that the rebellion would involve the Indians, Mendoza “secretly looked into the truth of the matter” by sending some of his most trusted men to spy on the Indians “under cover of darkness.”

Mendoza reported that his spies overheard rash talk, no more than “a sign” of a rebellion, but it was enough to frighten him. He immediately ordered the arrest of the African “king,” along with the other leading rebels, and then sent out the alarm to all the mining and farming communities. The die was cast and retribution would now be inevitable. “The blacks who were arrested confessed the truth. They had planned to seize the land,” Mendoza succinctly reported.

Years later, in 1612, an Indian nobleman called Chimalpahin, recorded details of another plot in his diary, writing that “the blacks of Mexico City had planned to rise up and kill their Spanish masters,” while the Spaniards were distracted by their Easter processions. “On Maundy Thursday,” as they paraded through the streets, the blacks would “turn them into dead men,” or so the witnesses at the trial testified. “This caused such fear among the Spaniards that the Easter processions were canceled.”

These African rebels of 1612 had dreamed of seizing control of Mexico themselves. They had chosen a king and queen and appointed a council of ministers and officers of the government. According to Chimalpahin, the Africans planned to subjugate the Indians, forcing them to pay tribute and serve them according to the Spanish model. They planned to murder all the male Spaniards: every man, boy, and babe-in-arms would be killed, except for a handful of priests who were to be castrated. The Spanish male bloodline was to be eliminated from Mexico.

Chimalpahin’s imagination perhaps ran away with itself as he expanded on the detail of this plot. All the old and middle-aged Spanish women were to be murdered too. Even most of the young señoritas would not be spared. Only those who were very pale-skinned or very pretty were to survive so that they could to be given to the African men as concubines. He also recorded that if these girls then gave birth to boys who were not obviously black or mulatto, then the fathers would be forced kill their own children. Pale-skinned daughters, however, would be saved for further breeding. This image of ferocious, vicious revenge exemplifies the terrible fears that paranoia can coax out of brutal oppressors when faced with rebellion by the oppressed. The terror is reduced to the primordial symbols of sexual impotence and the violation of defenseless womenfolk. It is a visceral terror that quickly incites savagery among the fearful.

During the night of September 24, 1537, the Spanish population of Mexico City reacted quickly. Mendoza mustered the conquistadors, 620 cavalry and countless infantrymen. The rebellion, real or imagined, was swiftly and brutally suppressed by this army of frightened, isolated Spaniards.

The convicted rebels were hanged and then quartered. Chimalpahin provides a chilling description of the retribution that followed the similar plot of 1612, when thirty-five black rebels were executed. The executioner, a mixed race man called Cristóbal, hanged the blacks with the help of his son. Eight new scaffolds were constructed for this purpose. Meanwhile, the victims were paraded through the streets on horseback, their upper bodies stripped bare, no doubt showing the marks of torture. At a quarter past ten in the morning, father and son began to string up the convicted rebels in the courtyard of the palace. “All died in agony, but they confessed,” and, now at peace with God, they left this life “crying out for forgiveness to their Savior, Our Lord Jesus Christ.” By one o’clock, Cristóbal and son had finished their work. The following day, they cut down the cadavers and the magistrates of the city ordered that they be drawn and cut in half. The remains were to be displayed about the town as a warning to others. But there was heated disagreement in the Audiencia. The more measured burghers argued that “it would be far from a good thing for all the dead to be quartered and hung up and left to rot in the main streets of the city, because their putrid stink would cause such disease as would be quickly carried about the town and it would make everyone sick.”

Twenty-nine of the corpses were beheaded and the heads alone were stuck up on the gallows. Their bodies were handed over to the African population of the city, who were allowed to bury what remained of their dead with the help of a number of priests. The other six bodies were quartered and the pieces were hung up on the main roads into town, the usual treatment of the bodies of the most feared criminals during the seventeenth century. Even in death they were reviled.

Following the suspected plot of 1537 and its brutal suppression, when the bloodletting was done, the Spaniards’ paranoia increased. An angry colonial official wrote to the Crown, expressing the sense of urgency and fear that had swept Mexico. He claimed to have repeatedly pressed Mendoza to improve the city defenses and was aghast that administrative concerns were impeding progress. It would be better to get on with it, the panicked patrician cried, “for God would not wish some rebellion or uprising to succeed,” such as “the revolt which nearly took place only days ago” and which was “arranged by the treacherous negros.” For it would be impossible to “save us all,” because there was no other city or town “so exposed as this.” Spanish Mexico City was in the hands of its enemies, he claimed, surrounded by water and Indian settlements. The terror this correspondent felt is palpable from his hurried, irrational prose.

By the middle of October 1537, Esteban can have had little doubt that, if at all possible, he should ensure his future lay away from Mexico City. He perhaps discussed his options with Juan Garrido, who was now making up his mind to go to Spain. But Garrido was a free man, and Esteban remained a slave—one mistake could cost him his life. The most promising opportunity for escape was obviously the coming expedition to the Seven Cities of Gold. He was of paramount importance to Mendoza and Zumárraga, and his views were listened to. His words could move the minds of powerful men. He could influence the makeup of the expedition, and in so doing could perhaps engineer for himself an opportunity to escape and return to a happier life among the Indians.

FROM THE MOMENT the four survivors first arrived in Mexico City, in 1536, Zumárraga had worked tirelessly, using his influential and highly efficient network of Franciscan contacts to lobby royal officials in Spain for authority over any expedition to the north. Mendoza had also fought hard for control of the expedition, but the viceroy was forced to admit defeat when he received a royal decree from Charles V declaring that the king “had been informed that there were religious men in Mexico of virtuous and exemplary life and high purpose who wanted to journey to newly discovered lands not yet conquered by the Spaniards.” The king had heard that “they intended to take the Holy Catholic Faith to the heathen natives and thereby do great service to the Lord.” “You are to grant them license for this purpose,” was the order.

Esteban was central to Zumárraga’s plans for a peaceful, religious expedition. He wanted Esteban to go as a guide and to take charge of the Mexican Indians who would accompany two or three Franciscan friars. He appointed his friend and Las Casas’s confidant, the French Franciscan Marcos de Niza, as the spiritual leader of the enterprise. Marcos was politically reliable, had a reputation as a good navigator and geographer, and seemed intrepid. He was by now an old hand in the New World and to Zumárraga, he seemed perfect for the mission of peaceful conquest.

On April 4, 1537, the Archbishop had written to a friend in Spain, enclosing Marcos’s signed declaration about the atrocities committed by the Spaniards who had conquered Peru. He was in no doubt about the value of this turbulent priest, expounding that Marcos was “a great man of religion, worthy of our Lord,” a man “whose virtues are proven and who is very zealous in his faith.” Marcos was so honest a man of God, Zumárraga enthused, that “in Peru the friars chose him as their Custos,” that is, their monastic leader. Marcos had then left Peru for Guatemala, where he wrote to Zumárraga about further Spanish atrocities. Zumárraga wrote back, asking him to come at once to Mexico.

To understand just how deeply Zumárraga trusted Marcos de Niza, however, it is necessary to look briefly forward almost a decade, to 1546, when Zumárraga lay sick, aware that death might snatch his soul from the world at any time and leave his earthly body to the worms. “My beloved brother,” he wrote to Marcos, “I have received your letter and the bed you sent me.” But “the cold wakes me,” he explained without complaint. “It is a good thing to do penitence now so as not to leave it all for the next life, seeing as this earthly life will not last long.”

By 1546, Marcos had retired to the beautiful, bucolic suburb of Xochimilco, which remains today a garden paradise offering heavenly respite from the pollution of Mexico City. Colorfully painted boats are gently punted along the canals which sit, grid-like, embracing the last “floating” fields, the champas of old Mexico. On Sundays, middle-class Mexicans flock here to picnic on these barges, while they are serenaded by boatloads of mariaches with their broad-brimmed hats, their fiddles and guitars, and their doleful songs of love and romance. But in the early morning, it remains a tranquil place of contemplation, where the cares of the world are washed from the mind by the gentle lapping of the waters against the muddy banks.

Marcos replied to Zumárraga’s lament in humble, beseeching tones, for he was preoccupied with his own material comfort and his own ill health. Zumárraga, he wrote, would be well aware of how Marcos had suffered when he left more temperate climes and knew that was why he had been sent to convalesce at Xochimilco. “As an orphan, with neither father nor mother to turn to for help,” he only had Zumárraga, he said. Marcos begged his friend to send him a “little” wine, which he needed for medicinal reasons, “as he was very wan and pale.”

Having stated his need for alcohol, he quickly moved on to an explanation of the logistics required for the wine to reach him. There is a strong sense that Marcos de Niza was a drunkard, perhaps an alcoholic, a devotee of Bacchus as well as of his Christian God. Zumárraga wrote back to him by return of post, promising that “while I live and for the duration of your illness, I will send you an arroba of wine each month.” Marcos no doubt prayed all the harder for the ailing Archbishop’s longevity.

Before his alcoholic retirement, Marcos de Niza had lied about what he saw during his expedition to the Seven Cities. In 1539, he had given wildly exaggerated reports about the north, elaborating on his story for almost any audience, eulogizing his promised land from the pulpit and in the barbers’ shops, talking of a place where the women wore jewelry of precious metals and the men wore belts of gold. Many were willing to open their wallets; for the price of a few drinks they could cock their eager ears and listen to the latest installment of his adventures.

In 1539, soon after Marcos’s return, a Spanish monk in Mexico had written glowingly to the prior of a monastery in Spain that the place discovered by Marcos was heavily populated and had a well-ordered society. There were walled cities with great houses. The people wore silken clothes and shoes. “I will not write about the great wealth of the place, for it is so rich that it will seem incredible to you,” the Mexican monk reported to his superior, but then he wrote about it anyway. “The temples are covered in precious stones, I think Marcos said they were emeralds, and the hinterland is home to elephants and camels.”

Even the shrewd Zumárraga was taken in and wrote enthusiastically to his nephew in Spain, telling him that Marcos had discovered an even greater land than Mexico. It was 400 leagues beyond the country conquered by Guzmán, near California, a place of large cities and plains where camels and dromedaries roam while quail fill the skies. The whole of Mexico, he said, wanted the chance to join the next campaign.

But Marcos’s verbal accounts were a tour de force of fantasy. In reality, Esteban had abandoned him and he had found nothing.

This hindsight about Marcos’s exaggerated storytelling and eventual disgrace is necessary to understand the strength of Zumárraga’s misplaced trust in Marcos. Even after Marcos’s account of his adventure had been exposed as a fake, the old Archbishop was kind to him. Years before, in 1538, even pragmatic Zumárraga had begun to commit the tempting sin of believing delusional tales that he wanted to believe. He laid plans for Marcos’s expedition, but his vision was unrealistic, an impossible dream born of his strong spiritual desire to see religious missions replace the cruel expeditions of the conquistadors. His faith, it seems, had blurred his judgment, for he was proposing that two or three Franciscans, guided by Esteban, and protected by a ragtag army of assorted Aztecs and Indians from northwest Mexico, would be able to evangelize all of North America. Even allowing for their uncertain knowledge of the geography involved, it was a far-fetched idea.

Antonio de Mendoza had risen to the rank of viceroy because of his pragmatism rather than his zeal. He no doubt realized that Marcos’s mission would almost certainly turn out to be little more than a fantastical charade. Without trespassing too obviously on Zumárraga’s royal grant, Mendoza began to arrange matters so that he could have as much influence as possible over the expedition. Most of all, Mendoza seems to have realized that while the expedition would conquer nothing, Esteban was clearly a very able explorer and communicator. The viceroy was determined to ensure that Esteban was given as much practical support as possible, for which it was obviously essential to strengthen the vulnerable military outpost at Culiacán, for a strong northern base camp was central to those plans. There had been worrying reports that the Spanish inhabitants and the garrison at Culiacán were so isolated and impoverished that they were considering abandoning the settlement altogether. The situation there been exacerbated by the arrest of Nuño de Guzmán, leaving a power vacuum in New Galicia. Mendoza now addressed that problem, appointing his protégé and close confidant, the young Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, as the governor of New Galicia. Coronado was to accompany Marcos and Esteban as far as Culiacán, with instructions to strengthen the settlement and convince the inhabitants to remain by means of a judicious mixture of bribery and threats.

Coronado, Marcos, and Esteban set out from Mexico City for New Galicia in the fall of 1538, heading back along the main highway which Esteban had traveled in the other direction two years before.