Epilogue

RESURRECTION

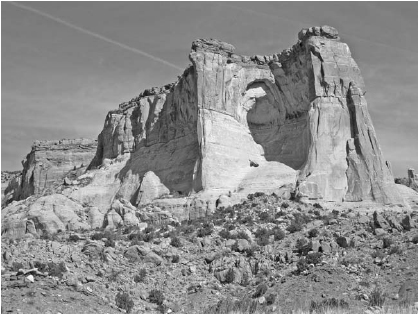

Dowa Yalanne, “Corn Mountain” (2006). The Zunis took refuge on top of this sacred mountain in times of trouble. Esteban is usually thought to have met his death at the pueblo of Kiakima, which nestled at the foot of these cliffs. (Courtesy of the author)

|

Should I die in a foreign land, |

Si muero en tierras ajenas, |

|

Then, who will mourn for me? |

Lejos de donde nací, |

|

Far from where I was born, |

¿quién habrá dolor de mí? |

|

Where I am a stranger unknown, |

¿Quién me terná compasión |

|

Who will look after me? |

Donde no soy conocido? |

|

Oh, unhappy and captive lover, |

¡Oh triste amador perdido |

|

You will never again be free, |

Cautivo sin redención! |

|

And your homeland is lost to thee. |

Extraño de mi nación, |

|

Far from where I was born, |

Lejos de donde nací, |

|

Who will mourn for me? |

¿quién habrá dolor di mí? |

|

P. Girón, sixteenth-century Spanish poet |

IN LATE JANUARY 2006, I arrived in the Sonora valley in northwest Mexico aboard a battered bus filled with schoolchildren, old women, and a few chickens, and got off at the small town of Baviácora. Large white crosses stood here and there all along the side of the road that wound up through the gorge above Corazones, as if they were messages from Esteban, but in reality marking the sites of many fatal automobile accidents. The bus rattled away down a long dusty hill leading out of town. The scene was so quintessentially evocative of the Hollywood image of Mexico that had it not been for Baviácora’s unquestionable authenticity, I might have felt as though I had escaped reality and become part of the fictional world.

No one near the bus stop had much idea if there was a place to stay. I crossed the plaza in the intense, dry heat and went into the relative cool inside a dark general store. The manager and owner, Miguel, sold me a bottle of beer, opened one himself, and as we slowly finished our drinks, he pointed me across the plaza, beyond the abandoned mission church, to a building opposite the town cantina, the Hotel San Francisco. As I looked across the square, I half wondered whether I might find a French friar called Marcos in the cantina.

I spent the afternoon with Miguel, drinking a strong homemade mezcal called bacanora and eating delicious elotes made by his wife. He knew all about Esteban, and Marcos de Niza, and Cabeza de Vaca. He told me that two years before some other gringo had passed through the town, inquiring after the dead. We chatted about life in Baviácora, and in due course Miguel tried to sell me a $100,000 share in the gold mine he was going to open up on a plot of land he owned in the hills to the east. He produced a ream of papers showing geological tests and estimates of the cost of extracting the gold and talked of the rising gold price in the international market. He explained that his son worked in some relevant government department, which would greatly ease the usual inconveniences of Mexican bureaucracy.

“Why,” I asked him, “are you inviting me to have a part of your business?”

“Why not?” he replied. “I need an investor and you are a gringo. A hundred thousand dollars is nothing to you.”

As dusk approached, I left him to his dreams and his bacanora and walked up to the cemetery, on a hill above the town. A bronze light gilded the headstones, glowed on the fresh floral wreaths, and tinged the landscape with a sepia hue as dust blew up from the fields in little eddies. Up on that hill, there was a cool breeze and a magnificent view of this strange, remote valley that still promised an improbable golden future for passing Europeans willing to surrender to the magic of hope.

It was clearer to me then than it ever has been that the seed from which Marcos de Niza’s account of the Seven Cities of Cíbola would grow must have been well watered while the friar rested here in this Land of Maize with its bacanora daydreams and promises of wealth.

I walked back down the tranquil streets filled with happy children at play and cowboy youths with fluffy mustaches and battered pickup trucks. I ate stinging hot tacos at the portable stall in the plaza and then went by a peculiar, long-abandoned church, a simple architectural fantasy in reinforced concrete, on the verge of collapse.

Tired, no longer hungry, and more or less sober I went back to my musty room in the Hotel San Francisco, spread out my books and photocopies, and turned my attention to the question of what had happened to Esteban.

IN THE SUMMER of 1540, Coronado’s expedition reached the Zuni River. They were exhausted, shattered by the almost impassable road through the Mogollon Rim along which Marcos had brought them. As they marched on the six towns, they found the Zunis ready for war. The men had retreated to Kiakima, the best defended of the pueblos, and turned it into a formidable redoubt. The women and children, the old and the infirm, had all been evacuated to the natural fortress of Dowa Yalanne, the sacred sand-red mesa above the town. Only the warrior braves remained, quietly determined to defend their way of life.

The battle was hard fought at close quarters, and Coronado was knocked senseless by a cataract of rocks hurled furiously from the flat-roofed houses. Unconscious, he was dragged to safety. But the Spanish conquistadors were at their strongest in adversity and they fought with unwavering resolve until their superior weaponry breached the defenses and the men of Cíbola finally capitulated. The routed Zuni army retreated to Dowa Yalanne. Many of their bravest young men were dead.

The Zunis did not see themselves as a warlike people, and it was now clear that engaging the Spanish army had led only to ignominious defeat. The humiliated Zuni bow priests now conferred, their authority under threat. They were no doubt thankful when Coronado sued for peace and tentative embassies began to shuttle between the opposing camps. Eventually, a delegation of Zuni elders was sent to conclude the truce.

Coronado reported to Mendoza that during those negotiations, the Zunis told him that they had killed Esteban “because the Indians of Chichilticale had told them that he was a bad man.” But he then added that the Zuni elders went on to explain that Esteban “was quite unlike” Coronado and his men, “who never kill women. For the truth was that Esteban went about murdering women” at whim. These assaults on the womenfolk, “whom the Indians love better than themselves,” were the reason that the Zunis killed Esteban, Coronado explained.

This is evidently slander, almost certainly invented by Coronado as a way of distracting attention from the excesses of his own army. Many surviving documentary sources clearly show that after various battles with Indians, Coronado was unable or unwilling to restrain the psychopathic sexuality of many of his own men. They had raped and abused the Indian women mercilessly.

By contrast, all the documentary evidence indicates that Esteban was quite a different character from Coronado’s evildoers. While it is reasonable to speculate that the four survivors’ shamanism may have led them to take sexual advantage of Indian women from time to time—possibly even prolifically, and there is some evidence that Esteban happily continued that practice as he traveled north to Cíbola with Marcos—even that largely imaginary picture of Esteban as a promiscuous lover hardly fits Coronado’s description of him as a sexual predator who liked to rape and butcher women as a way of life. There is a deep-seated, familiar racism about that image of Esteban as a black sexual predator, a racism which will persist as long as the image is treated as true. It is high time that this explanation of what happened at Zuni is buried once and for all.

So the Zunis’ motive for Esteban’s murder, as reported by Coronado, is demonstrably spurious and clearly originated with crimes committed by Coronado’s men. Without that motive, the Zunis’ confession, as it were, loses all credibility. In fact, Coronado betrayed his own lack of confidence in that confession when he explained to Mendoza that he was “perfectly certain” that Esteban was dead, not because the Zunis had confessed, but because his men had “found many of the things which Esteban wore.” But it is a strange kind of logic that leads directly to the conclusion that a man’s possession are, in his absence, evidence of his death. It is equally likely that Esteban had simply changed his clothes, perhaps adopting the dress of his Zuni hosts.

During his peace negotiations, Coronado heard that the Zunis had living with them a lad from Petatlán, Bartolomé, who had traveled there with Esteban and who spoke the Mexican Nahuatl language. Coronado quickly recognized that this youth would make an invaluable interpreter, and he demanded that the Zunis hand him over. But the Zunis dissembled: at first they said he was dead; then they claimed that he had been taken to a nearby town, Acucu. Faced with this apparent intransigence, Coronado quickly raised the stakes and issued angry threats. The Zunis soon handed over Bartolomé.

As I looked over the evidence in the Hotel San Francisco in Baviácora, I noticed an extraordinary and possibly very significant anomaly: in an age that attached so much importance to eyewitness testimony, Coronado had failed to record Bartolomé’s account of what had happened to Esteban. Coronado must have asked, but there is no record of the answer. Whatever that answer may have been, it seems almost certain that Bartolomé said nothing to confirm that Esteban was dead. In fact, it seems likely that he either said nothing at all about Esteban or said something that Coronado preferred not to record.

My cross-referencing and examination of the Spanish documents led me to the conclusion that there was insufficient evidence to bring the Zunis to trial for Esteban’s death in a modern courtroom, let alone convict them of murder or manslaughter. It was time to turn to the Zunis themselves for a clue to the events of the summer of 1539.

THE NEXT DAY, at dawn, I walked back through the long shadows thrown by the early morning light across the broad plaza of peaceful Baviácora. The sun was a lance’s length above the horizon and the air was crisp with the brisk cool of daybreak which comes before the heat. I ate tacos at the stand and had coffee. Miguel’s store was closed up and there were no early dreams for sale. The bus came and stopped, and I continued my slow journey up the Sonora valley.

By lunchtime, we had arrived at the small town of Arizpe, erstwhile capital of the Mexican Internal Provinces, from where, in the eighteenth century, a Spanish governor ruled all northern Mexico, California and Washington, Arizona, and New Mexico. I ate quesadillas in a roadside shack next to the narrow, homely highway and afterward sat in the shady town square to wait for the afternoon bus that would take me up onto the high and arid flatlands of Cananea. I opened my rucksack and eased the package of maps and battered photocopies from among my dirty clothes. I turned to a remarkable account of life at Zuni Pueblo during the late nineteenth century, written by a remarkable character called Frank Hamilton Cushing, “the man who became an Indian.”

Cushing was an eccentric Boston aristocrat who arrived in Zuni in 1879 as a member of an anthropological expedition sent to the southwest by the Smithsonian Institution to gather information about Indian society and culture. The expedition scientists set up camp at a respectable distance from the pueblo and began to observe the comings and goings of the “natives” as they went about their daily business. But Cushing soon became dissatisfied with the haughty methods of investigation employed by his superiors, and the intransigent secrecy of the Indians. He realized that this complete lack of communication would make meaningful research impossible. So, with the courage and arrogance of his social class, Cushing ignored the express orders of his commanding officer by abandoning the expedition camp and, quite uninvited, taking up residence in the quarters of the Zuni governor. That governor, a sanguine, kindly character called Palowahtiwa discovered his unannounced and uninvited guest slinging a hammock across his rooms and generously took in the intruder, albeit with an appropriately measured lack of grace. Cushing remained at Zuni for four years, becoming part of the Zunis’ world, in due course taking the requisite number of scalps to be initiated as a bow priest.

Cushing was a fine example of the frequent cultural anomalies that enriched the Victorian age. He had stoically suffered an abject childhood of alienation from his parents and peers due to his unhealthy constitution and his love of solitude. At Zuni, he now found companionship and an outsider’s freedom. He had arrived begging for shelter, but he was to leave a hero who successfully championed the Zunis’ cause, using a western armory of law, politics, and journalism. He fought a long and bitter struggle in Washington to correct a bureaucratic error that had annexed rich farmlands and important water sources from the Zuni reservation.

The potential parallels between Cushing and Esteban are unmistakable. Both men represented and symbolized a colonial invasion from which they themselves were spiritually divorced. Both men arrived at Zuni very much a part of those colonial forces, bringing with them a sense of danger and suspicion from which each was anxious to separate himself. Both offered themselves to the Zunis as guests, each a traveler from a far-off land, each seeking food and shelter. Each was eager to engage with the Zunis and their ways.

Caught between two cultures, but born a “good” New Englander, Cushing inevitably turned adventure into a virtue by writing about Zuni and in the process invented modern anthropological practice. Never before had a researcher subsumed himself within a native culture so as to observe and experience its every aspect, and the descriptions and images he published were unique. But by finally publicizing Zuni secrets, Cushing permanently broke his spiritual bond with the land and people who had made a valiant warrior out of the boy who first knocked hopefully at the Zuni door. He has never been forgiven for betraying the vows of silence which rule the ritual and religious world at Zuni. Cushing is remembered as a traitor.

His accounts of Zuni are consequently invaluable to the outsider. In the square at Arizpe, I now turned to my copy of his classic monograph Zuñi Breadstuff, in which he records the Zunis’ account of how they first began to grow wheat at the pueblo.

A group of elder Zunis told Cushing that many generations before, “certain grey-robed water-daddies,” Franciscan friars, “brought and planted wheat germ and taught us how to grow it.” These friars had arrived at the time that “the Indians of the Land of Everlasting Summer,” the Sonorans, had come to Zuni “with long bows and cane arrows.” They were accompanied by “Black Mexicans,” who carried “thundering sticks which spit fire,” and they were dressed in “coats of iron.” But “our ancient ancestors at Kiakima” then “greased their war clubs with the brains of the first of those Black Mexicans.”

What “bad-tempered fools!” the Zuni elders lamented of their ancient ancestors. They explained to Cushing that as a consequence, the “mustachioed” Spaniards grew angry and “appeared in fear-making bands and grasped the life-trails of our forefathers until they became like dogs after a drubbing.”

Cushing came to the conclusion that this first “Black Mexican” must have been Esteban, as he explained in a lecture he gave to the Geographic Society of Boston. He arrived to give the talk dressed in his own interpretation of Zuni costume, just as Esteban wore his shaman’s accoutrements when he was in Mexico. Cushing began with the theatrical opening of a natural dramatist.

“Like the teller of Indian tales,” he began, “I bid you back more than three hundred and fifty years.”

An able raconteur, Cushing now carried his audience from the elegant eastern hall of learning to the firelight world of a distant evening in his little room at the heart of Zuni Pueblo. His audience soon felt as though they were there at his side as he sat reading an “old work of travel.” They could almost see the four tribal elders who entered the semi-European enclave of his room and sat down to roll cigarettes. As they smoked, they watched, until one man spoke up, talking as if for the rest.

“What do the marks on the paper-fold say?” the old men wanted to know.

“Old things,” was all that Cushing was prepared to reply.

“How old?” they asked.

“Three hundred and fifty years.”

“How long is that?”

The four old men could not conceptualize such a long passage of time. But they were intellectually resourceful and slowly laid out a chain of 350 corn kernels, “in a straight line across the floor.”

They huddled over, counting the kernels and remarking here and there, “Now that’s one father. This is his son,” marking out the generations.

Eventually they established that ten or eleven generations were roughly equivalent to Cushing’s 350 years.

“Why!” they exclaimed. “That must have been when our ancients killed the Black Mexican at Kiakima.”

“Tell me more,” said Cushing.

“It is to be believed that a long time ago, when roofs lay over the walls of Kiakima, when smoke hung over the house-tops, and the ladder-rounds were still unbroken—It was then that the Black Mexicans came from their abodes in Everlasting Summerland. One day, unexpected, out of Hemlock Canyon, they came, and descended to Kiakima. But when they said they would enter the covered way, it seems that our ancients looked not gently on them. But with these Black Mexicans came many Indians of Sonoli, as they call it now, who carried war feathers and long bows and cane arrows like the Apaches, who were enemies of our ancients. Therefore these our ancients, being always bad tempered and quick to anger, made fools of themselves after their fashion, rushed into their town and out of their town, shouting, skipping and shooting with sling-stones and arrows and war clubs. Then the Indians of Sonoli set up a great howl, and they and our ancients did much ill to one another. Then and thus, the black Mexican, a large man with Chilli lips, was killed by our ancients right where the stone stands down by the arroyo of Kiakima. Then the rest ran away, chased by our grandfathers, and went back toward their country in the Land of Everlasting Summer. But after they had steadied themselves and stopped talking, our ancients felt sorry, for they thought, ‘Now we have made bad business, for after a while, these people, being angered, will come again.’ So they felt always in danger and went about watching the bushes. By and by they did come back, those Black Mexicans, and with them many men of Sonoli. They wore coats of iron and even bonnets of metal and carried for weapons short canes that spit fire and made thunder. Thus it was in the days of Kiakima.”

Cushing told his Boston audience that he was still utterly ignorant of the Spanish histories of Marcos and Esteban when he heard this story from the Zunis. But we know this was not strictly true, because he had written about Marcos, and Coronado, and Cabeza de Vaca, and other ancient chroniclers of the Spanish Empire in letters he had sent to Washington long before he took up residence in Zuni Pueblo. I wondered how much Cushing had elaborated his account and to what extent he had prompted the old Zuni historians into telling the story he expected to hear rather than the story that they usually told.

I also wondered how much Zuni oral tradition had been influenced by alien accounts of their history. For much of modern history, Zuni has been constantly visited by outsiders: anthropologists, ethnographers, archaeologists, and Anglo academics looking for their own long-lost souls; by Spanish Catholics looking for the lost souls of the Zunis, and by Protestant priests looking to do good. What imprint did these foreigners leave behind them with their constant questions, their constant quest for the intangible truth, and their constant quest to educate?

By way of explanation, it is instructive to tell a story that took place high up in the Andes of Peru, where the Incas built their awesome palaces and temples of vast and irregularly shaped stone building blocks that were so smoothly and perfectly cut that it is impossible to fit even a razor blade between them. Over the years, thousands of archaeologists had tried, without success, to work out how the Incas managed to do this. Then, one archaeologist discovered at an important Inca site the remains of some kind of saw for cutting stone. He quickly worked out how the contraption was meant to work and built one for himself, convinced that he had solved this ancient problem. For a time, his colleagues believed that he had, until they all realized that he had in fact found the remains of an experiment discarded by a nineteenth-century scholar who had also hoped to solve the mystery.

Had the Zunis been so often asked about each documentary detail of Esteban’s death by western scholars that those details had become part of the Zunis’ landscape, just as the discarded saw fleetingly became a part of Inca achitectural history?

It is interesting that both Zuni accounts of the “Black Mexicans” that were recorded by Cushing emphasize a sense of the ancestors’ stupidity in killing the first Black Mexican. The nineteenth-century Zuni elders, it seems, saw this aggressive behavior as out of character, for, as all the books had led me to expect, the Zunis saw themselves as traders who relied on peaceful relations with their neighbors and preferred to avoid conflict. Understood as a parable rather than history, the Zuni story of the Black Mexican clearly preaches a message of peace, for their unprovoked aggression is shown to lead directly to the arrival of the angry Spaniards. And the truth of a parable, of course, is not in the narrative itself, but in the morality of the tale.

I was to discover that even today, Zunis tend to show incomprehension and a sense of disbelief when faced with Spanish accounts of how their ancestors murdered Esteban. It is not a story that Zunis are comfortable with, almost as though it does not belong to their own sense of history.

Among my travel-worn photocopies, I had an account of Esteban’s death which was published in 1997 and which had been given by a Zuni scholar and historian called Edmund Ladd as a spontaneous contribution to an academic conference on the Coronado expedition. Zuni on the Day the Men in Metal Arrived is a masterpiece of oral academia of a kind all but lost in the e-mail world of modern universities.

Ladd told the story of Esteban’s arrival at Zuni, but while he gave the impression that he was working within an oral tradition, he also pointed out that oral traditions lack detail and that his account was in fact based on “other” sources, tempered by Zuni spiritual and moral values. In reality, Ladd, it seems, needed to rely on Spanish documents for the detail. And so, with evident reluctance, he found himself forced to repeat the explanation for Esteban’s death that had been offered by Castañeda in 1540. He concluded that Esteban’s fatal mistake was to declare himself a leader of the Spaniards and that he must therefore have been killed because he was believed to be a spy working for an evidently powerful enemy. But Ladd was clearly puzzled that the Zunis should have committed the murder at all, and he insisted that they would have been friendly at first, “for it is their nature to be” so. If the Zunis had been guilty of the killing, their descendants seemed less than convinced.

I looked up from my books. Children were fooling around in the street outside the closed-up Cathedral of Arizpe and it was very hot and the town was asleep. It reminded me of Spain at siesta time in the summer. I chatted with a shoeshine boy while he shined my shoes. He refused payment, but I insisted and so he sat down once more and polished them all over again.

At exactly two o’clock, precisely on time by the town hall clock, the afternoon bus arrived and I left Arizpe. We drove up and out of the Sonora valley, leaving the ancient Zunis’ “Land of Eternal Summer” for the flat deserts of the border country. There were cactus and purple prickly pears, and a warm breeze blew in through the open door at the front. That night I slept in the unpleasant border city of Nogales in a cheap hotel and drank tequila in a disagreeable bar full of the drunken dregs of some fraternity house. It was my last night in Mexico.

THE FOLLOWING MORNING, I passed the lines of nervous pedestrians with their cheap luggage full of cheap medicines, walked across the border into the United States of America, and found a van full of Mexicans who would take me to Tucson. The driver was a graduate of Guadalajara University with a particular interest in British constitutional history. As he drove us through the back streets of Tucson’s Mexican barrios and industrial estates, dropping off the other passengers, he talked to me about Magna Carta, the Glorious Revolution, the founding of the United States, universal suffrage, and the principles of the Common Law. When we reached my destination, the Arizona University law school, I stayed chatting for a while before we shook hands and I shouldered my filthy rucksack. Dirty, tired, and happy, I went into the air-conditioned modern building and looked for Jim Anaya, the Indian lawyer who specialized in the rights of indigenous peoples whom I had met in Seville. He had promised to take me to Zuni.

As I sat in the law school office, watching Jim and his friend Rob Williams faxing and phoning their various contacts on my behalf, I noticed a slight sense of frustration. I felt trapped as I watched the impatient cultural machinery of the modern world clash with the slow, measured civility of Zuni society. But it was a fleeting sense of unease that evaporated in the sunshine of the following morning as the three of us set out on the long drive to Zuni.

As we traveled, I briefed Jim and Rob about Esteban. I told them about Marcos de Niza, the unreliable witness; and about the various reports of Esteban’s death in the other Spanish accounts. I read key passages from some of the accounts and summarized others. Both Jim and Rob sit as tribal judges within the Indian legal system. If anyone could pass judgment on the charge of Esteban’s murder which History had leveled at the Zunis, they could.

We drove up the Zuni valley and reached the modern pueblo, a pretty, scruffy place, full of life, and pulled into the parking lot in front of the tribal council offices. Inside, by extraordinary good fortune, we met a member of the tribal council called Edward Wemytewa, who has worked hard to keep oral tradition alive among the young people of the tribe, increasingly influenced by television and drawn to the more material world beyond their reservation. He also knew Zuni history, which made him wary, determined to engage with the outside world on his own terms. He seemed torn between silence and enthusiasm. But he also knew a lot about Esteban, and any historian is always pleased to meet a colleague. So, with reservations, he seemed happy to talk. It helped that he seemed to have mistaken Jim for somebody else.

We sat around a low coffee table in the entrance hall of the tribal council offices and Ed slowly began to tell us what he knew about Esteban’s arrival at Zuni. He engaged easily with Rob and Jim, while managing to welcome and exclude me at the same time. I was glad that I had briefed Jim and Rob in the car, because I was out of my depth. As I watched, their legal training and familiarity with Indian law quickly showed in a subtle cross-examination.

Ed is a master storyteller with a keen academic mind, and his tale of Esteban’s death at Zuni was filled with detail and told with rare clarity. But as Ed spoke, I silentely noted that almost every fact in his story could be explained with reference to one or another of the Spanish chronicles. Nothing he said was new to me, except for one curious and emotive symbol. In passing, Ed associated Esteban with the image of a snake. This was the one detail I had never come across in my research, the only Zuni secret that Ed let slip.

When Ed had finished speaking, I tried to press him about his reference to a snake and asked him whether there was some secret about Esteban that he could not tell me, something kept hidden in the Zunis’ histories and traditions. But instead he told me about the night dances the Zunis celebrate in winter, when the different kiva societies perform rituals during which the men dress as ancestral characters from Zuni history and the spirit world. As they dance, the spirits come to these actors and the supernatural world becomes fleetingly tangible.

These spirit-dancers are known as kachinas, and Ed told me about a “beautiful black kachina” with a sexual magnetism that cast a spell over the women who saw the dance. He implied that he thought the Zunis might have killed Esteban out of straightforward sexual jealousy and not because he mistreated their women. I had already learned about the black kachina Chakwaina, the monster kachina who is common to all the different pueblo cultures. Anthropologists report that a number of pueblo legends associate Chakwaina with Esteban and some have implied that in this way Esteban’s spirit lives on in the pueblo world. It was beginning to seem that the Zunis may well have killed Esteban, but that he had then been resurrected as a potent kachina. Yet, even as Ed began to suggest that the black kachina might offer an explanation of what had happened to Esteban, he immediately withdrew the idea and refused to confirm that the black kachina was really Esteban’s spirit at all. I was skeptical.

Later, we met Jim Anaya’s old Zuni friend Jim Enote, who showed us around the house he was building on the outskirts of the modern pueblo. We sat chatting in a big white room, which felt cool and refreshing after the stuffy council building and the relentless heat outdoors. I explained to Jim that I was trying to find out about the Zunis’ history of what had happened to Esteban and I told him that Ed’s account seemed to be based on the Spanish sources. Then I asked him about the black kachina.

He began to tell us that the black kachina had nothing to do with Esteban, but then stopped and asked, slightly surprised, with a twinkle in his eye, “Did Ed tell you that?”

Jim Enote then talked diplomatically about Ed’s expertise as a historian and his knowledge of Esteban’s story, but quickly turned the conversation to a conference he had recently attended in Canada and the problems he had with funding his work on making Indian cultural maps of North America. I started to believe that Jim Enote had not only given away his own view that the black kachina had little or nothing to do with Esteban but had also let slip his surprise that Ed should have done so.

As I reflected on our conversation, I thought I understood what Ed had really been doing when he told me about the black kachina. I suspected that as he knew that I had come to Zuni for a story, and as a storyteller himself, he was glad to offer me a story to tell. He wanted to give me what I had come for. But as a historian and a protector of Zuni traditions, he gave me a story I could have found elsewhere and then refused to certify it as true. Ed kindly gave me what I needed, closure for Esteban and an end for a book, and then left it to me to decide whether the story was true. It would have been so easy to poetically resurrect Esteban as the black kachina Chakwaina here, now, on these pages, and then leave it at that.

Then, as I thought more about Ed’s account of Esteban’s death, his murder at Zuni hands, I became convinced that like Ladd and the Zuni storytellers described by Cushing, Ed too had been struggling to find a motive for an act that was completely out of character for his culture.

The Zunis had given a deeply symbolic meaning to their story of Esteban’s murder by directly associating it with their terrible defeat by Coronado. It had become a classic example of the way in which victims of savage oppression so often try to tell their story so as to blame themselves, because through that guilt they can regain a sense of control over their own destiny. So long as the Zunis believe that their gods had punished their forebears for Esteban’s murder by sending Coronado and other Spaniards to conquer them, they can still sense the part they played in their own downfall. But if Coronado’s coming was not their responsibility, but was simply fate, then their only conclusion must be that their gods had abandoned them. And how can man die more miserably than amid the ravaged houses of his ancestors and forsaken by his gods?

And so, even as Edward Wemytewa told us his story, that very process of telling it, it seemed to me, was leading him to trust the Spanish sources less and less. Caught between two American cultures, Zuni and Anglo, Ed is an erudite man for whom the western historical tradition is as important a source of knowledge about Zuni history as Indian oral history should be to western scholars interested in America’s past. By the tenets of either tradition and their different ways of understanding the past, Esteban’s arrival marks, with unusually vivid symbolism, a critical point in Zuni history in particular and an important moment in American history in general. Of such historical moments are myths and legends born. So, like Ladd before him, Ed too had turned to Spanish sources to find out more about this ancient event, and he too seemed uncertain of what to make of those sources.

Ed, I know, guards some secret about Esteban safely preserved within the tight-lipped community of a kiva society or the Zunis’ priesthoods. But those privy to such things are sworn to secrecy, and so such knowledge has no place in print. From what little I have learned about the complex world of the Zunis, it seems to me that the only plausible reason they might have had for executing Esteban was that they considered him a sorcerer. Under traditional Zuni law, only sorcery was considered a capital crime.

That afternoon Jim, Rob, and I drove out to Dowa Yalanne. The great sand-pink mesa rises steeply from the grassy river valley, dominating the landscape with its crags and buttresses. The remains of Kiakima are clustered at the foot of a wide, sweeping amphitheater, where two towers of sheer rock stand like sentinels over sacred Zuni shrines, indistinctly marked by prayer sticks among the ruins of the former pueblo. The walls of the “covered way” that led through Kiakima, described by Cushing’s informants, can still be seen, a few vertical slabs that stand like tombstones marking the place where the legends claim Esteban died. It is a place of extraordinary spiritual calm.

In the evening, after this peculiar pilgrimage to the possible site of Esteban’s unmarked grave, the three of us sat in a shack at the side of the main road eating tacos and burritos and drinking colas. We talked about Esteban, Ed, and the haunting tranquillity of Kiakima, and we began to wonder what to do before bedtime. Then the waitress told us that the whole town was at a basketball game and so after supper we drove to the high school. The parking area overflowed into the surrounding desert and Jim heaved the car up onto a verge near a fence. After some searching about, we found a back entrance to the gymnasium and walked into the middle of the basketball game. There were still a few empty seats halfway up one of the stands, and we picked our way through the steep terraced rows, packed with screaming supporters.

I know nothing about basketball, but Jim had played in college and pointed out the unorthodox tactics necessarily used by the Zuni team because their players were all short compared with their Navajo opponents. They rushed the length of the court with cannonball vigor, relying on a low center of gravity to outwit their gangling opponents. Sadly, despite their raw enthusiasm and evident skill, by the third quarter it was obvious that the size and power of the Navajos were prevailing and the home crowd succumbed to a growing sense of disappointment.

That disappointment was soon vented in angry outbursts directed at the referee. The atmosphere gradually intensified and as it did, Rob was riveted. “I guess this is what happened to Esteban,” he said. “All those anthropologists talk about how the Zunis are peaceful and not emotionally expressive. But these guys are screaming for blood!”

Cultural comparisons are easily misleading, and I had little idea how to properly qualify or quantify the aggression shown by the Zuni spectators at this basketball game. But compared with the murderous tribal hatred of European and South American soccer fans, which often leads to physical violence, the crowd at Zuni seemed passionately benign. I was still not convinced that the Zuni bow priests had murdered Esteban.

In fact, the cultural importance attached by the Zunis to hospitality and the avoidance of conflict raised an intriguing question. Why, I wondered, when Coronado first approached them with his thirsty, hungry, fatigued, weakened army, did the Zunis—again uncharacteristically—resort to conflict rather than dialogue?

The arrival of many strangers is always good cause for apprehension, but it is an unlikely reason for a thoughtful, considered, self-confident nation with a preference for peace to suddenly go to war without provocation. For the Zunis to attack Coronado, they must have had very good reason to think it was the right thing to do.

Very very few men familiar with the Spaniards’ true nature can have visited the six Zuni villages before Coronado. Perhaps only one, Esteban. Perhaps, it occurred to me, Esteban warned his hosts at Zuni what to expect from the Spaniards. Did he then move on farther north, away from the relentless advance of the Spanish frontier? Or did he stay at Zuni and urge the “bow priests” to engage Coronado in battle? Did he believe that they had a chance of victory and tell them to strike while the Spaniards were at their most vulnerable?

It would be easy to believe that in the aftermath of defeat, the bow priests turned on the African outsider. Perhaps they chased him from their midst, blaming him for their downfall. Perhaps they charged him with sorcery and had him executed?

AS I WRITE these inconclusive final words, I must be flying more or less over Zuni. It is a strange and disappointing feeling. I have told you how Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca ended up in Spain, disgraced after he failed as governor on the River Plate. We know that Andrés Dorantes de Carranza ended his days as a farmer and innkeeper on the road from Veracruz to Mexico City. We even know that Alonso del Castillo Maldonado was a landowner who lived in Puebla de los Angeles and Marcos de Niza retired to an alcoholic dotage in Xochimilico. But I find it more and more difficult to believe that Esteban was killed at Zuni and I have no idea what really happened to him. Just as his origins in Africa are obscure, so too his death in America has proved to be a mystery.

My flight took off from Phoenix, symbolically enough; and it may be that Esteban can rise from his Zuni ashes and reach towards the heavens, which he had so often claimed were his home. I have the transcript of a fragment from a lost and unpublished chronicle buried in the Mexican archives. It records that “when Esteban reached the Mayo River, he was so taken with the handsome and beautiful women of the Mayo Indians that he hid himself away” from Marcos de Niza and the Spaniards. There, “following the custom of the country, he took four or five wives.” By 1622, “one of Esteban’s sons had become a captain or lord of certain lands on the banks of the Mayo River, in the municipal district of Tesio.” He was of “noticeably mixed race, tall and lean, with sallow features,” a man called “Aboray.”