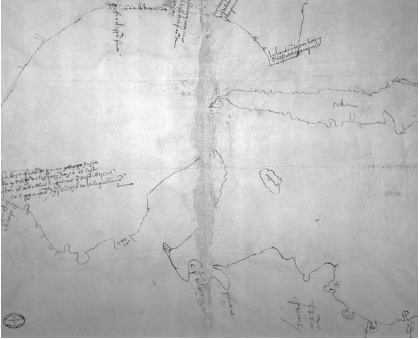

The earliest known map of the Gulf of Mexico (c. 1519). The River and Bay of the Holy Spirit (“Río del Espíritu Santo”) is the last feature labeled toward the west of the north coast of the gulf. (Courtesy of Archivo General de Indias; MP México 5)

“Look at Odysseus’s journey or Jason’s voyage or the labors of Hercules, they are but fiction and fable. So read them as such for that is how they should be read. And do not admire the wonders in them, for they bear no comparison with the hardships of these sinners, who traveled such an unhappy road.”

(Fernández de Oviedo, Spanish Historian Royal, c. 1540)

THIS IS THE story of how history is written, the history of Esteban’s story, and also the tale of the first men in history to cross North America. It is a narrative of uncertainty, conjecture, and historical truth.

HISTORY IS THE origin myth of the white man. It tells us about our ancestors, their heroes and wars, about how we came to live as we do, about our gods and our morality. It defines our values and reveres our political institutions. It offers a continuous story of our civilization, from ancient Greece and Rome right up to the foundation of our own nation-states. I write, evidently enough, from the perspective of my own personal history.

We were taught from childhood that history is the true story of the past, based on facts. We learned that it is not the historian’s job to dramatize his story in order to make it exciting. We learned that the historian’s style of writing should be a little bit boring, for he must let the facts speak for themselves. It is his job to tell the truth, only the truth, and as much of the truth as he can. As the great Spanish novelist Miguel de Cervantes explained in 1615:

A poet may speak or sing of events, not as they really happened, but as they should have been; but the historian must write down events, not as they should have been, but as they really happened, neither embellishing nor suppressing anything that is true.

And yet we might pause to question if that is possible. How do we know that history is fact? How does a historian know that what he tells us is true?

As we all learned, as soon as our parents dared to let us know such things, any story we are told may be true or false. We learned quickly to talk of “tall stories” with a hint of smile, and we even praise a “good story,” with something of a wink in our eye. These are the tales traditionally told by hunters, fishermen, soldiers, and other travelers. These are the stories that are based on facts but which are embellished with fiction. Such stories are entertaining, but more often than not they are also the boasts of a hero who tells his own tale. For which reason, we do not believe him. But do we believe him if the heroes of his stories are his parents, or his grandparents?

What should we make of the legend of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table? Clearly, it is not factual history, with its magical swords and invincible heroes, but what kind of story is it? How many of us are bold enough to say it is not true? How different is what we know about King Arthur from what we know of George Washington or Billy the Kid?

In recent years, many historians have been intrigued by this new manifesto of self-doubt, while others have exploded with apoplexy at this revolution from within their subject. In order to understand the history of how historians have arrived at this collective sense of uncertainty, it is useful to look briefly at some of the different ways in which the history of the Spanish conquest of Mexico has been written—not least because to do so also helps to explain the background to the story I am going to tell in this book.

Probably the most influential work written in English about this subject is The History of the Conquest of Mexico by William Hickling Prescott (1796–1859). As a law student in Boston, he was blinded by a youthful prank and was forced to give up the law. Fortunately, he instead turned his attention to writing history. He is said to have had such a prodigious memory that he was able to compose the chapters for his books while out riding in the morning and then write them up in the afternoon, using a special writing contraption for the blind which he had bought in London. His writing style suggests that he had a formidable personality, and he wrote history with a strong sense of drama and great literary flair. What he saw in his mind’s eye more than made up for the real world he could not see.

Prescott was perhaps the most brilliant historian of his age, but he was also very much a child of his time and of the patrician social class into which he was born. As a result, his account is an aristocratic drama about his central character, Hernán Cortés, the commander of the first European army to march into Mexico and reach the Aztec capital, in 1519. Prescott used the work of many Spanish historians who had glorified Cortés, but he set particular store by the letters that Cortés himself sent back to Spain describing his discoveries and conquests. Yet was Prescott right to believe what Cortés had written? Did he stop to wonder critically enough why Cortés wrote them? Did a Spanish general have any reason to tell the truth?

Yes and no. The basics are certainly true. A small force of Spaniards, perhaps as many as 1,500, seized control of the mighty Aztec Empire. But Cortés was also a turncoat and a rebel who had betrayed his own superior, the governor of Cuba appointed by the Spanish crown. Cortés wrote his letters in order to prove that he was no traitor to his sovereign, the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, king of Spain, to convince Charles that he done nothing wrong and was in fact an imperial hero. But he also wrote in order to dazzle the Spanish court with a brilliant story of bravery and fabulous wealth, and he took care to send those letters to Spain along with tangible proof of his success in the form of gold and silver.

Cortés’s letters tell a story that is ideal material for a man like Prescott with a strong sense of republican patrician honor. An inspiring and rebellious general drawn from the gentry led a small army of intrepid soldiers to an astonishing and glorious victory won against all odds over a great empire. They founded a new “republic,” full of hope. God had clearly been on their side. As a parable, it suited Prescott and it suited America. But is it too good to be true? After all, how did a handful of Spaniards conquer the great Aztec Empire? It sounds more like an Arthurian legend than fact.

As the western world became more democratic, explanations for the conquest of Mexico began to embrace the humble as well as the mighty. The history of Mexico came to be seen through the eyes of one of the less important soldiers in Cortés’s army, Bernal Díaz del Castillo. Díaz wrote his True History of the Conquest of New Spain in the 1550s because he was outraged that Cortés had contrived to claim all the glory for himself in the official account. But the True History was left unpublished until more egalitarian historians took an interest during the nineteenth century, welcoming Díaz’s claim that all the Spaniards who had been involved, great and small, deserved the credit. But this was still the story of a purely European victory.

When the Great European Powers were forced to surrender their American colonies, Europeans found themselves writing their own history as a story of loss and defeat. Writing about the conquest of Mexico, historians now characterized the Spaniards as foreign actors on an indigenous American stage. They read the Spanish accounts again and noticed that Cortés and his men were only part of the story. They had in fact managed to capture the Aztec capital at Tenochtitlán, later renamed Mexico City, only because they were supported by coalition of indigenous armies drawn from a population long subjugated and persecuted by the Aztecs.

As the great colonial empires broke up and slavery and segregation were abolished, American and European societies became home to the diverse many rather than the homogeneous few. Today, history can no longer simply be the origin myth of the Christian white man alone and must now explain the origins of our world to citizens from very varied backgrounds. But this situation presents a new set of problems.

Historians need facts with which to fill the blank pages of their histories, and although archaeologists and other students of the past can help, written documents have always been the historian’s staple. We need the accounts of events written by the protagonists themselves, the official reports written by others at the time, the histories written by contemporary commentators and historians; we need the wealth of detail to be gleaned from legal documents and mundane account books. At the time of Cortés’s conquest of Mexico, those documentary sources were almost all produced by Spaniards. How are we to write an accurate and balanced history of the events of that period when the Aztec Mexicans themselves left so few accounts of their own history? And it is more difficult still to write about Native American Indian history, which was an oral culture that did not produce written sources.

Similarly, the history of the Africans who served the Spanish Empire is not easy to write, because the sources were written by the masters and not the slaves. But, buried beneath the surface of the historical sources there lies a fragmentary, uncertain African-American history, and the subject of this book, Esteban, is one of the few examples of a sixteenth-century African slave whose achievements were so outstanding that it is possible to piece together his story from the contemporary Spanish documents.

Esteban became the pivotal character in the amazing adventures he and his Spanish companions lived through during the first crossing of North America in recorded history. The story is well documented because an official report based on the testimony of three Spanish survivors—Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, Andrés Dorantes de Carranza, and Alonso del Castillo Maldonado—was compiled in 1536.

How foreign and unfamiliar these names seem to us today, even though the first crossing of lands that later became the United States of America is so well documented. Nothing, perhaps, could be more indicative of the biases in our traditional understanding of when and where American history began. Long before the Pilgrim fathers established their colony, long before any significant European settlement on the east coast, Esteban had become one of the greatest explorers in the history of North America. In due course, he led a Spanish expedition deep into modern Arizona and New Mexico, and he may have died within the frontiers of the modern United States. Esteban was the first great explorer in America; he was also, perhaps, the first African-American.

In 1902, a distinguished African-American veteran of the Spanish-American War, Major Richard Robert Wright, concluded an academic paper by asking why Esteban had “remained practically in obscurity for more than three and a half centuries.” “The answer is not difficult,” he replied, for “until recently historians were not careful to note with any degree of accuracy and with due credit the useful and noble deeds of the Negro companions of the Spanish conquerors, because Negroes were slaves, the property of masters who were supposed to be entitled to the credit for whatever the latter accomplished. The object of this paper is to direct attention to this apparent injustice.” He went on to remark that “if someone more competent will undertake a thorough investigation of the subject the purpose of the writer will have been accomplished.”

I am considerably less competent than Major Wright to undertake the investigation he called for so long ago, but I am better placed to do so, for I have the benefit of a century of research by others, access to the Spanish archives, and time afforded me by a generous publisher. That my investigation has been as thorough as Major Wright would have wished is unlikely, for his were the exacting standards of his age; but more than 100 years later, it seems that this historical account of Esteban’s life is still long overdue. In order to understand how Esteban came to be where he was, go where he went, and do what he did in America, we need first to learn something of how Spain came to have such a powerful empire in the New World.

IN AD 711 an Islamic army crossed the narrow Strait of Gibraltar, a channel only eighteen miles wide separating Spain from Morocco—Europe from Africa—and quickly overran the weak Spanish kingdom. In the mountains of the far northwest, a few Christians resisted these invaders, but Islamic Spain soon developed into a great intellectual and artistic culture and its principalities and caliphates became centers of religious and political tolerance. Still, occasional periods of puritanical fanaticism led to social unrest and cultural censorship. During those periods of trouble and conflict, the tiny Christian kingdom in the far north was able to expand its territories and grow in strength.

The relationship between the Christian north and the Muslim south was complicated. Mostly, alliances were formed and broken with no regard for religion. But the call of the crusade or jihad was a potent political force, and from time to time border conflicts degenerated into outright holy war. More often than not, the Christian Spaniards won those wars, so that eight centuries after the Islamic invasion, almost all Spain was Christian once more. Finally, in 1492, Granada, the last remaining Islamic kingdom, capitulated to the Catholic Monarchs, as the joint King and Queen of Spain, Ferdinand and Isabella, were known.

The character of Christian Spain had been defined by this long history of reconquista, the “reconquest.” It was a history of bloody battles, border raids, hostage-taking, and ransom. Spain was a land of warlords, overmighty aristocrats who won their wealth by violence and who ruled their estates with an iron fist. They were proud of their warrior status and their pure Christian heritage. Blond and blue-eyed, they despised work and commerce, the business of peasants, Jews, and Muslims. But there was no more of Spain to conquer. They had, quite literally, reached the sea.

In the crusading euphoria surrounding victory over Granada, the rulers of Spain decreed that the Jews should convert to Christianity or be expelled. Legend has held that money stolen from these refugees paid for Columbus’s voyage. That tradition is largely myth, not fact, but Columbus was able to manipulate the triumphant spirit of the age in order to persuade the Catholic Monarchs to support his proposed voyage to China across the Atlantic. He had been searching for support for this scheme for ten years or more, but no one had ever taken him seriously because he had badly miscalculated the size of the world, as his detractors well knew. It is a curious fact, but on Columbus’s own map, there was quite simply not enough space for America to exist. Where Florida is today, Columbus expected to find Japan. Suddenly and quite unexpectedly, the Spanish Crown gave its backing to a sailor most people believed to be a madman.

Because we have a copy of his journal, Columbus’s first voyage to America is well documented. We know, for example, that when he landed on Cuba, on November 6, 1492, he sent his ambassadors deep into the interior of the island to contact the Chinese emperor. Nearby, he believed he would find India and the Spice Islands.

For decades, the Spanish discoveries in the Caribbean were largely disappointing, a series of islands populated by poor, primitive peoples and offering few signs of wealth. Although the great continental mass promised more, early explorations failed to find anything of real value. But Cortés’s conquest of Mexico completely changed European attitudes to America. At the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlán, the conquistadors found a sophisticated civilization that was unimaginably rich in gold. The story spread fast of the adventurers who had been humble peasants and farmers in Spain and were now rich noblemen in an exotic land. But their position was precarious from the outset because Cortés and his men had disobeyed a strict order from the governor of Cuba that they should trade only on the mainland coast and that both settlement and conquest were prohibited. Cortés resorted to a legal trick to circumvent this problem, using a medieval law to turn his temporary army camp of flimsy tents into a town. This town was a bureaucratic fiction, but Cortés and his men could argue that the town council was legally independent of Cuba and could therefore authorize his campaigns in Mexico. Cortés and his men were well aware that while they had seized their golden prize from the Aztecs, their authority to do so was questionable under Spanish law.

In 1520 they were forced to defend their ill-gotten gains. That year, an experienced military captain and Caribbean slave trader, Pánfilo Narváez, was sent with a powerful army to arrest Cortés. But Narváez was to become one of the first men to experience the true power of Aztec gold. As the two Spanish armies prepared to do battle on Mexican soil, Cortés ordered some of his most trusted men to secretly cross the battle lines. He sent them armed with glittering gifts of unrivaled value and outlandish stories about the wealth of Tenochtitlán. Narváez’s men were quickly seduced, his army deserted him, and Narváez himself was taken prisoner. Cortés kept his fellow general in a “gilded cage,” regaling him with fine foods and luxurious living, but he took his prisoner by force to Tenochtitlán to see the splendor for himself. In due course, Narváez returned to Cuba defeated, but restless with greed.

On Cuba, the captains of slaving ships sent to raid for Indians on the northern coast of the Mexican Gulf reported improbable rumors of other wealthy cities deep in the heartland of the great swath of territory that today stretches from Florida to Arizona. Narváez hurriedly sailed for Spain, and in 1526 he obtained permission from Charles V to explore and settle the north coast of the Gulf of Mexico. He was given the title of Governor of Florida—Florida being the name the Spanish gave to the whole of the American south, from Georgia and Florida to modern New Mexico. Overnight, he became the legal European ruler of an immense, but unexplored, world.

Narváez’s expedition landed at Tampa Bay at Easter 1528, and in June he headed inland with 300 men. They ran into trouble almost immediately. Their progress was obstructed by mangrove swamps, they were harried by hostile Apalachee Indians, and they were ravaged by disease. Narváez’s men were soon forced to slaughter their horses for food while they constructed five inadequate boats in a desperate attempt to reach Mexico by sea. When they finally set sail, the tiny, overloaded vessels were blown about and washed this way and that in the winter storms. Narváez himself was last seen shouting from his boat, being dragged out to sea, accompanied by a young page boy. Many men drowned; others were ruthlessly murdered by the coastal tribes of Louisiana and Texas; others fought among themselves and in their desperation descended into cannibalism.

Only four men survived this tragedy: Esteban, Cabeza de Vaca, Dorantes, and Castillo. Eight years later, in 1536, they told an astonished audience in Mexico the remarkable story of how they had survived by becoming shamans and bringing peace to the Indian tribes who revered them and how in return they were treated as gods. Their story came to epitomize for their contemporaries the struggle between good and evil at the heart of the Spanish Empire. They inspired Christian missionaries to preach a peaceful and spiritual conquest, but their reports also fired the fiercely greedy imaginations of the powerful conquistadors who competed for control of Spanish Mexico.

THIS BOOK TELLS the story of how Esteban came to be central to the survival of his companions and how, as a result, he was appointed by the viceroy in Mexico as the de facto military commander of the first Spanish expedition to explore deep into Arizona and New Mexico in search of the mythical lands of Cíbola and the Seven Cities of Gold.

Esteban’s history is, in part, the story of how that first extraordinary crossing of America came to be told and written, first by the Spanish survivors of the expedition and then by later historians. It is also the story of how the history of that strange expedition to the Seven Cities of Gold came to be written.

In telling those stories, this book shows how Esteban was marginalized in the contemporary Spanish documents because he was a slave. As a result, he has been ignored or misunderstood by historians ever since. As well, in showing how it is possible to reconstruct Esteban’s biography, this has become a book that asks questions about the ways in history may legitimately be written.

So this is a book about history and storytelling. Part One begins at the point when the four survivors of the Narváez expedition—Esteban, Cabeza de Vaca, Dorantes, and Castillo—began to tell the outside world the story of their first crossing of North America. It begins when they are reunited with Spaniards in northwest Mexico and traces their onward journey to the Spanish frontier outpost at Culiacán and then on to Guadalajara and Mexico City. Their knowledge of the previously unexplored north made them important players in the politics of Mexico City and the Spanish Empire, and that role determined how they developed and embellished their story. Part One ends as they complete their official testimony to the authorities in Mexico City.

Esteban’s personal history begins in Part Two, which looks at the evidence for who he was and where he came from. It seems likely that he left North Africa during a period of terrible hunger, only to reach Spain while it too was suffering a devastating famine. We know that Esteban must have passed through the great Spanish port of Seville on his way to America, and Part Two ends with a description of that city during the period when Esteban was there.

Part Three returns to storytelling and examines the documentary evidence. First, it looks at the important difference between the two main versions of the story of the first crossing of North America which have survived and which are available to us: one written by a survivor, Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca; the other by a contemporary historian, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo.

Part Four tells the story of Pánfilo Narváez’s failed expedition to Florida, describing the preparations in Seville, the voyage across the Atlantic, the arrival in the Caribbean, and the landing on the Florida coast at Easter 1528. It describes the slow destruction of Narváez’s army and Esteban, Dorantes, Castillo, and Cabeza de Vaca, tracing their travels along the Gulf Coast, through Texas, up the Rio Grande, and across New Mexico and Arizona. Part Four ends when they first make contact again with the Spanish world in 1536.

Part Five describes how, in 1538, in Mexico, Esteban was appointed as a guide and military commander of an expedition sent by the viceroy to search for the mythical Seven Cities of Gold, which were believed to lie somewhere north of the lands he had explored with Cabeza de Vaca, Dorantes, and Castillo, deep into Arizona and New Mexico.