Embodied cognition, communication and the language faculty

INTRODUCTION

Human language use and understanding involve several motor and perceptual processes: linguistic sounds are articulated by a speaker and perceived by an addressee. What is characteristic of human verbal communication is that a speaker utters and an addressee perceives sentences of natural languages, i.e. complex grammatical sequences of words with both phonological and meaning (or semantic) properties that they inherit from the phonological and meaning properties of their syntactic constituents. Interestingly, much recent neuroscientific research into language comprehension has highlighted the existence of tight connections between aspects of language understanding (particularly, the understanding of action words) and the organization and activity of the human motor cortex. This chapter will examine the evidence for the correlations between language comprehension and the activity of the human motor system, and their significance for understanding language understanding.

Before proceeding, however, it is worth sketching the complex relations between language use, communication and the language faculty (see the second section for further elaboration). Humans can use words and sentences of natural languages in virtue of being endowed with a dedicated language faculty. Furthermore, they do so for various purposes, including notably (verbal) communication. Not all communication, however, need be verbal: much of it consists also in ostensive-communicative gestures (e.g. deictic pointing). As Sperber and Wilson (1986: 49) define it, an ostensive gesture is a stimulus produced by an agent to make manifest her intention to make something manifest to an addressee. Nor do people use language solely for the purpose of communication: one can also use language for clarifying one’s thoughts, reasoning and making calculations. Furthermore, in addition to spoken languages, humans can also use sign languages for the same purposes. Finally, the gestures used by deaf signers are interestingly different from commonly observed spontaneous gestures accompanying the use of verbal language in regular speech (see Goldin-Meadow, 1999; see also Corballis, this volume).

Recent findings about correlations between language understanding and the human motor system seem to corroborate the so-called embodied cognition research programme. As the label for the embodied cognition (hereafter EC) framework suggests, EC stresses the contribution of the body and bodily processes, i.e. sensory and motor processes, to human thinking and cognition in general (cf. Gallagher, 2005). Using (spoken or sign) language for communicative purposes is clearly an intentional action governed by a speaker’s communicative intention. It clearly involves a number of motor processes such as executing articulatory movements of the vocal tract or hand movements. Conversely, the process whereby the addressee of a communicative act understands the speaker’s intended meaning clearly starts with the perception of the ostensive auditory and visual stimuli produced by the agent of the act.

This chapter takes it for granted that the process whereby the addressee of a communicative act understands the speaker’s intended meaning starts with the perception of the auditory and visual stimuli displayed by the speaker. Nor will it probe Liberman and Mattingly’s (1985: 2) motor theory of speech perception, according to which ‘the objects of speech perception are the intended phonetic gestures of the speaker, represented in the brain as invariant motor commands that call for movements of the articulators through certain linguistically significant configurations’. Instead, the basic question to be addressed in this chapter is: in human verbal communication, which (if any) aspects of an addressee’s understanding of the meaning or content of a speaker’s utterance depend on the addressee’s embodied cognitive processes, i.e. sensory and motor processes?

The chapter falls into four sections. In the first section, I spell out the basic assumptions of the EC framework. As I explain in the second section, a speaker’s utterance derives its meaning from two complementary sources: the speaker’s meaning (or communicative intention) and the linguistic meaning of the sentence used by the speaker to convey her communicative intention. Furthermore, the linguistic meaning of the sentence in turn depends on both the linguistic meanings of the constituent words and the syntactic principles of combination. In the third section, I examine recent experimental evidence showing that activity in a participant’s motor system contributes to her understanding of the meanings of some lexical items, specifically action verbs. In the fourth section, I examine the putative contribution of mirror neuron activity to an addressee’s ability to represent a speaker’s communicative intention.

THE LOGICAL GEOGRAPHY OF EMBODIED COGNITION

As Shapiro (2007: 338) puts it:

embodied cognition is an approach to cognition that departs from traditional cognitive science in its reluctance to conceive of cognition as computational and in its emphasis on the significance of an organism’s body in how and what the organism thinks.

So conceived, EC involves both a negative and a positive claim. What advocates of standard versions of EC primarily reject is the computational view of the mind as a disembodied (Turing) machine manipulating formal (i.e. amodal) symbols according to syntactic rules. To a large extent, EC’s rejection of the computational view of the mind (also called ‘early cognitivism’ by Gallese and Lakoff, 2005) overlaps with the conclusions drawn by the philosopher John Searle (1980) from his famous Chinese room thought-experiment against Strong AI, i.e. the joint views that the brain is a digital computer and that understanding a natural language can usefully be thought of as a computer program (see Glenberg and Kaschak, 2002).

Whereas Searle (1980, 1985, 1992) further argued that what digital computers lack is both consciousness and intrinsic intentionality, advocates of EC instead put the human body (or embodiment) at the core of human cognition. As Clark (2008a: 37) puts it, EC ‘depicts the body as special, and the fine details of a creature’s embodiment as a major constraint on the nature of its mind: a kind of new-wave body-centrism’. Clearly this body-centred approach to human cognition should not be acceptable to an advocate of Cartesian ontological substance dualism between minds and bodies (see Anderson, 2003). Against the Cartesian ontological separation between minds and bodies, advocates of EC argue for the ‘intimacy of the mind’s embodiment and embeddedness in the world’ (Haugeland, 1998). However, two preliminary clarifications are in order. First of all, the human brain is of course part of the human body. Now advocates of the computational view of the mind who also accept ontological physicalism assume that cognitive processes are just brain processes. So the question arises whether what primarily matters to EC is that (some, much or all of) human cognition depends on the possession and use of human bodily parts, in addition to a human brain, or instead on the possession of a human brain capable of representing human bodily parts (see Prinz, 2008; Goldman and de Vignemont, 2009).

Second, Clark (2008a, b) further argues that, whereas some advocates of EC, who embrace the body-centrist version of EC, stress the unique role of the human body in cognitive tasks, others espouse instead an externalist version of EC that ‘depicts the body as just one element in a kind of equal-partners dance between brain, body and world, with the nature of mind fixed by the overall balance thus achieved’. As Clark (1997: 53) put it, ‘mind is a leaky organ, forever escaping its “natural confines” and mingling shamelessly with body and with world’. On this version of externalism, which Clark and Chalmers (1998) call the extended mind, the body is just the brain’s local or proximal environment. Similarly, Prinz (2008), who draws a related distinction between embodied and situated cognition, also observes that advocates of situated cognition are ipso facto advocates of embodied cognition on the grounds that ‘the body can be regarded as part of the environment of the mind or brain—it’s just a very local part’.

Furthermore, it is convenient to distinguish at least three degrees of commitment to embodiment on either the body-centrist or the externalist/situated version of EC, each of which corresponds to one of three strategies whereby advocates of EC might want to reject the disembodied computational view of the mind: the anti-representationalist strategy, the virtual representation strategy and the symbol-grounding strategy.1 The most radical EC strategy is to embrace some straightforward version of anti-representationalism and eliminate altogether the notion of mental representation (or mental symbol) from the explanatory vocabulary of cognitive science. Perhaps the best-known illustration of anti-representationalism in this sense is Rodney Brooks’s (1991) slogan according to which we don’t need to mentally represent the world because ‘the world is its own best model’.2 But as Fodor (2009) has recently retorted, this just looks like a category mistake: ‘the world can’t be its own best representation because the world doesn’t represent anything; least of all itself’.

A less radical and more plausible EC strategy is the virtual representation strategy recommended by the enactivist approach to the domain of visual perception (see O’Regan and Noë, 2001). The basic idea is to exploit Wilson’s (2002) suggestions that all or some of our cognitive work can be off-loaded on to the environment and that off-line cognition is body based. As the philosopher Alva Noë (2004: 50) puts it, ‘there’s no need to re-present the world on one’s own internal memory drive. Off-loading internal processing onto the world simplifies our cognitive lives and makes good engineering and evolutionary sense.’ Noë (2004) further interprets the results of experiments on change-blindness to show that our perceptual experience of the details of a visual scene does not arise from a detailed visual internal representation.3 Rather, the detail belongs, so to speak, to the outside world. Instead of building a rich internal representation of visual details, our visual system is taken to enable us to entertain a virtual awareness of the details of a visual scene. On the enactivist account, our virtual awareness of visual detail arises from our implicit knowledge of the availability of the visual detail, i.e. where in the outside world it is located and which bodily action to perform to retrieve it if needed. What makes the enactivist emphasis on the virtuality of one’s awareness of visual details a version of EC is that, according to enactivism, access to visual details depends on the agent’s body and bodily actions.

Arguably, the claim that one’s awareness of visual details is virtual is closely linked to the externalist version of EC, according to which our ability to experience visual details relies not just on internal states of one’s brain, but on one’s ability to coordinate distal states of the environment in the broad sense, bodily actions, bodily parts and brain processes. Assuming, however, that a visual representation of a perceived scene may be less detailed than the represented scene, it hardly follows that one’s visual experience is virtual in the required sense, i.e. that it does not arise from a mental representation of the scene, let alone that one’s visual experience does not supervene upon the internal states of one’s brain (or that it lies outside one’s head). The fact that some features of a visible display (e.g. Mt Sainte-Victoire in the South of France) are not fully represented in, for example, a Cézanne painting shows that the representation (the painting) differs from what it represents (i.e. Mt Sainte-Victoire itself). It is quite conceivable that there are details in the Mt Sainte-Victoire itself that are not represented in the Cézanne painting. But it would be odd to conclude, on these grounds, that the depicted content of a Cézanne painting is virtual and/or that it is not a property of the canvas (a physical object). Similarly, the fact that an individual’s mental representation differs in some respects from, or lacks some of the features of, what it represents does not show that the mental representation is not a state of the individual’s brain.

Unlike the two previous strategies, the goal of the third EC symbol-grounding strategy is neither to deny the existence of mental symbols, nor to virtualize their contents. Instead, the goal is, in Barsalou’s (1999) well-known terminology, to deny the existence of a special class of mental symbols, i.e. concepts, classically conceived as both amodal and arbitrary mental symbols, whose respective (non-phonetic) form stands to their respective content in the same arbitrary relation as the phonetic forms of words stand to their meanings. On the symbol-grounding strategy, all mental symbols derive their meanings from the activity of basic sensory and motor processes. As Mahon and Caramazza (2008: 59–60) depict EC’s symbol-grounding strategy, ‘conceptual content is reductively constituted by information that is represented within the sensory and motor systems […] conceptual processing already is sensory and motor processing’.

As Barsalou (1999), Jeannerod (2001, 2006), Barsalou et al. (2003), Gallese and Lakoff (2005) and Gallese (2008) have further argued on behalf of EC, both visual imagery and motor imagery can be thought of as processes of embodied simulation whereby the brain areas respectively devoted to visual processing and motor execution could underlie the processing of the meanings of, for example, colour words and action words. From this standpoint, far from being:

represented in amodal symbolic form, […] conceptual knowledge is embodied, that is, mapped within our sensory-motor system […] the sensory-motor system not only provides structure to conceptual content, but also characterizes the semantic content of concepts in terms of the way that we function with our bodies in the world.

(Gallese and Lakoff, 2005)

Arguably, few (if any) advocates of the computational view of the mind would want to deny that an agent’s body enables her to act, move in space, feed and mate. Nor would they deny that an agent’s bodily parts and organs are likely to affect the non-conceptual character and content of mental representations and mental operations involved in both perceptual and motor tasks.4 Rather, what makes EC’s symbol-grounding strategy controversial is that it is a strikingly empiricist view of the format and content of concepts and conceptual representations (see Prinz, 2002). Some philosophers (e.g. McDowell, 1994) have denied the distinction between conceptual and non-conceptual content because they assume that the content of perceptual experiences is already conceptual. Empiricist advocates of the symbol-grounding strategy deny the same distinction for the opposite reason: they assume that all content is sensory or perceptual. On this empiricist approach, whereas the phonological structure of the English word ‘dog’ stands in an arbitrary relation to its meaning or reference (i.e. hairy barking creatures), the symbolic vehicle of the concept DOG does not stand in an arbitrary relation to its meaning or reference. Nor could its content be encoded in an amodal format independent from either the distinct visual experiences caused respectively by the vision of a poodle, an alsatian, a dalmatian and a bulldog, the auditory experience caused by processing the acoustic stimulus produced by a barking dog, the tactile experience caused by touching a particular dog or the olfactory experience caused by smelling a particular dog.

THE THREE-LAYERED MEANINGS OF UTTERANCES

Much contemporary linguistic research recognizes that linguistic utterances should be ascribed three distinct layers (or levels) of meaning. First, complex sentences of natural languages have a linguistic meaning that depends on the meanings of their constituents and the syntactic rules of combination. Second, the content explicitly expressed by the utterance of a sentence depends not only on the linguistic meaning of the uttered sentence, but also on various aspects of the context of utterance. Third, by uttering a sentence, a speaker both expresses an explicit proposition and also implicitly conveys much further information. Thus, recognition of the three layers of meaning depends on two distinctions: the distinction between a sentence and an utterance and the distinction between the explicit and the implicit content conveyed by an utterance. As it will turn out, the latter distinction first highlighted by Grice (1967/1975, 1968, 1969) displays the fact that human verbal communication is an intentional and rational activity. The complex content of an utterance reflects a speaker’s communicative intention, which is a social intention, since it is directed to an addressee, whose task is to retrieve the speaker’s meaning. As Grice argued, a speaker’s communicative intention is a social intention of a complex sort, such that not all social intentions count as communicative intentions.

Understanding the meaning of a speaker’s utterance is the output of two distinct complementary cognitive processes, one of which is the addressee’s ability to process the linguistic meaning of the sentence uttered by the speaker, the other of which is his ability to determine the speaker’s meaning. (Recent evidence reviewed by Willems and Varley (2010) shows that language processing and communication rely on partly distinct neural systems.) In this joint process, the questions arise: how much of the content of the utterance has been coded into, and can be decoded from, the linguistic meaning of the utterance? How much depends on the addressee’s ability to represent the speaker’s communicative intention? On the one hand, each sentence of L is a grammatical string of words and expressions that belong to the lexicon (or dictionary) of L, i.e. a sequence of words ordered according to the syntactic rules of L. As a result, the complex linguistic meaning of any sentence of L depends on both the simpler linguistic meaning of each constituent expression and the syntactic rules of combination. On the other hand, a speaker’s utterance of a sentence from her native language L for the purpose of verbal communication is an intentional action whereby she conveys to her audience her communicative intention.

Unlike sentences of natural languages, which are generated by grammatical rules, utterances are created by speakers as part of their intentional speech acts. Utterances, not sentences, can be shouted in a hoarse or high-pitched voice and tape-recorded. Now, the full meaning of an utterance goes beyond the linguistic meaning of the uttered sentence, in at least two distinct aspects: both its representational content and what Austin (1962) called its ‘illocutionary force’ (i.e. whether the utterance is meant as a prediction, a threat or an assertion) are underdetermined by the linguistic meaning of the uttered sentence.

As Chomsky (1957, 1965) argued fifty years ago, any speaker of a natural language L tacitly knows the grammatical rules that enable her to produce and understand novel sentences of L that she has never perceived before. By assumption, the lexicon of L is a finite list of lexical items. But as Chomsky (1957, 1965) further argued, there is no grammatical upper bound on the length of sentences of natural languages.5 If there is no grammatical upper bound on the length of sentences of natural languages, then it follows that there is no grammatical upper bound either on the cardinality of the set of sentences belonging to a natural language. Since the grammar of a natural language must be knowable by a finite human mind, it must be finite. Only if it includes recursive rules (i.e. rules that can take as input their own output indefinitely) can a finite grammar generate an open-ended set of sentences from a finite lexicon. If this reasoning is correct, then, as Hauser et al. (2002) argue, the core of the human language faculty (the human language faculty in the narrow sense) must include recursive rules with the capacity to embed hierarchically organized phrases within phrases. One issue to be addressed in the fourth section is whether EC has the (motor and/or sensory) resources to account for the recursivity of the human language faculty.

While the goal of generative grammar is to address the issue of how the linguistic meanings of sentences depend on the linguistic meanings of their constituent lexical items, the philosopher Paul Grice (1957, 1968, 1969) laid the foundations for a novel inferential model of human communication, which stood in sharp contrast with the code model. Unlike a decoding process that maps a signal on to a message associated to the signal by an underlying code (i.e. a system of rules or conventions), an inferential process maps premises on to a conclusion, which is warranted by the premises (see Sperber and Wilson, 1986). Not all human communication is verbal, but when verbal, human communication exploits the combination of two distinct kinds of cognitive processes. On the one hand, tacit knowledge of the grammar of a natural language is knowledge of a code that maps the phonological properties on to the semantic properties of any expression belonging to a given natural language. Chomsky (2000) further argued that the evolutionary function of the human language faculty is to enable any human child to acquire knowledge of the grammar of the language spoken by members of her linguistic community. On the other hand, for verbal communication to succeed, the addressee must infer the speaker’s meaning or communicative intention from her verbal behaviour (which is only a cue). Similarly, in non-verbal communication, an agent’s hand gestures are only a cue on the basis of which the addressee’s task is to infer the agent’s communicative intention (see the fourth section).

On Grice’s novel framework, human communication can be seen as a cooperative and rational activity in which the task of the addressee is to infer the speaker’s meaning on the basis of her utterance, in accordance with a few principles of rational cooperation. Grice introduced the concept of speaker’s meaning, i.e. of someone meaning something by exhibiting some piece of behaviour that can, but need not, be verbal or linguistic. According to Grice, for someone S to mean something by producing some utterance x is for S to intend the utterance of x to produce some effect (or response) in an audience A by means of A’s recognition of this very intention. Hence, Grice characterizes a speaker’s meaning in terms of communicative intention, where a communicative intention has the peculiar feature of being reflexive in the sense that part of its content is that an audience recognize it. As Csibra (2010) has recently put it, Grice’s insight is that ‘a communicator wants not only to convey a message but also that the addressee recognize his intention to do so, and would not be satisfied with the outcome of his action unless this recognition is realized’. Sperber and Wilson (1986), who argue for a relevance-based approach, preserved Grice’s insight into the dual nature of a speaker’s meaning or communicative intention by drawing a distinction between the speaker’s informative intention to make a set of assumptions manifest to her addressee by producing a piece of ostensive behaviour and the speaker’s communicative intention to make her informative intention manifest to her addressee.

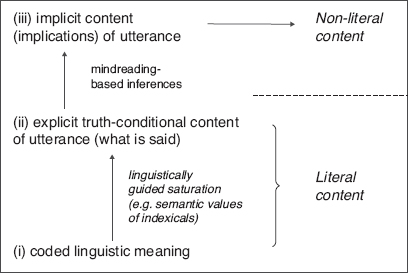

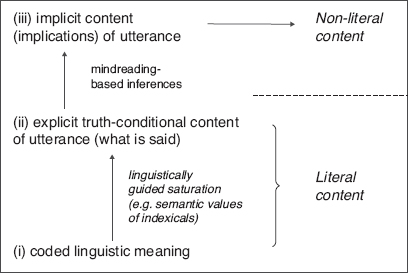

On the basis of this cooperative framework, Grice (1967/1975) further argued that, in addition to the content explicitly expressed, a speaker’s utterance also implicitly conveys what he called conversational implicatures. For example, suppose that Bill asks Jill whether she is going out and Jill replies: ‘It’s raining.’ For Jill’s utterance about the weather to constitute a response to Bill’s question about whether Jill is going out, additional assumptions are required, such as, for example, that Jill does not like rain (i.e. that, if it is raining, then Jill is not going out), which, together with Jill’s response, entails that she is not going out. In this example, the proposition that Jill does not wish to go out is a conversational implicature that can be derived by Bill from both his own contextual question and further background assumptions about Jill’s personal psychology.6 On Grice’s cooperative framework then, human verbal communication involves three layers of meaning: (i) the linguistic (or conventional) meaning of the sentence uttered, (ii) the explicit content expressed (i.e. ‘what is said’) by the utterance, and (iii) the implicit content of the utterance (its conversational implicatures).

Figure 1.1 The tripartite Gricean picture of meaning. From the bottom up: (i) (bottom) linguistic meaning of uttered sentence coded by the grammar of natural languages fails to express truth-valuable propositional content because it includes indexical expressions whose values can only be fixed (or saturated) by contextual information; (ii) (middle) truth-evaluable propositional content, i.e. what is explicitly said by, or literal content of, utterance; (iii) (top) implicatures, i.e. propositions implicitly conveyed, or non-literal content expressed, by utterance.

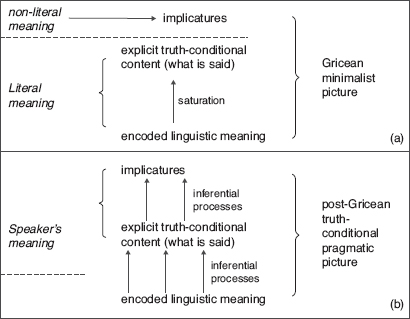

In the last fifteen years or so, a new truth-conditional pragmatic approach has emerged, whose core thesis is that what is said (i.e. the explicit content of an utterance or what is evaluable as being true or false), not just the conversational implicatures of an utterance, depends on the speaker’s meaning. This pragmatic approach to what is said further extends the Gricean inferen-tialist model of communication. Grice urged an inferential model of the pragmatic process whereby a hearer infers the conversational implicatures of an utterance from what is said. But he embraced the minimalist view that what is said by an utterance departs from the linguistic meaning of the uttered sentence only as is necessary for the utterance to be truth-evaluable. According to minimalism, appeal to contextual information is always mandated by the presence of some linguistic constituent (e.g. an indexical expression such as ‘I’ or ‘here’) within the sentence. By contrast, advocates of truth-conditional pragmatics argue that minimalism underestimates the extent to which what is explicitly said by a speaker’s utterance is under-determined by the linguistic meaning of the sentence uttered. As a result, the determination of what is explicitly said by a speaker’s utterance itself (not just the conversational implicatures of her utterance) may involve contextual pragmatic processes including the representation of the speaker’s meaning, while this process need not be triggered by some linguistic constituent of the sentence uttered.

Sperber and Wilson’s (1986) relevance-theoretic approach squarely belongs to truth-conditional pragmatics. This approach is so-called because Sperber and Wilson (1986) accept a cognitive principle of relevance according to which human cognition is geared towards the maximization of relevance. Relevance in turn is a property of an input for an individual at t: it depends on both the set of contextual effects and the cost of processing, where the contextual effect of an input might be the set of assumptions derivable from processing the input in a given context. Other things being equal, the greater the set of contextual effects achieved by processing an input, the more relevant the input. The greater the effort required by the processing, the lower the relevance of the input (see Carston, 2002, for elaborate discussion).

The controversy between the Gricean minimalist and the truth-conditional pragmatic pictures can be illustrated by means of the following examples. Suppose a speaker utters: ‘The picnic was awful. The beer was warm.’ For the second sentence to offer a justification (or explanation) of the truth expressed by the first sentence, the assumption must be made that the beer was part of the picnic. According to a minimalist account, the assumption that the beer was part of the picnic is a conversational implicature of the utterance (more precisely, an implicated premise). According to an advocate of truth-conditional pragmatics, the concept linguistically encoded by ‘the beer’ could be pragmatically strengthened and enriched into the concept expressible by ‘the beer that was part of the picnic’ that is part of what is explicitly said by the speaker’s utterance. Conversely, other examples may involve processes of conceptual loosening or broadening. For instance, imagine a speaker’s utterance in a restaurant of ‘My steak is raw’, whereby what she says is not that her steak is uncooked but rather that it is undercooked. Similarly, to understand what a speaker says by uttering ‘The ATM swallowed my credit card’, the hearer must loosen some of the conditions of application of the concept encoded by the verb ‘to swallow’ since swallowing is restricted to living things and ATMs are not living things. (For further examples, see Recanati, 2004.)7

Figure 1.2 Minimalist vs. truth-conditional pragmatic pictures of meaning. (a) Displays the orthodox Gricean minimalist picture that minimizes the gap between the linguistic meaning of a sentence and the explicit content of the utterance of the sentence, by reducing it to the saturation of indexical expressions by contextual information. (b) Displays the truth-conditional pragmatic picture according to which not only (i) the implicit content is derived from the explicit content of an utterance by (inferential) pragmatic processes, but also (ii) the explicit truth-conditional content of an utterance is derived from the linguistic meaning of the uttered sentence by (inferential) pragmatic processes.

EMBODIED MOTOR COGNITION AND THE MEANINGS OF ACTION VERBS

The discovery of mirror neurons in non-human and human primates showed that the same brain areas (the inferior frontal gyrus) are involved in the execution of some actions and the observation of the same actions performed by another agent (see Rizzolatti and Craighero, 2004). Much recent investigation has revealed that the same brain circuit (the so-called ‘mirror system’) that is involved in the planning, execution and observation of bodily acts performed by others is also involved in one’s understanding of the meanings of verbs describing the same actions (see also Corballis, this volume). I shall review some selective evidence for the role of motor processes in semantic processing.

For example, Buccino et al. (2005) conducted both a behavioural and a transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) experiment. In the TMS experiment, participants listened to sentences expressing either hand or foot actions while the experimenters applied TMS to the hand and the foot/leg motor areas of participants and recorded motor-evoked potentials (MEPs) from participants’ hand and foot muscles. Buccino et al. (2005) report that MEPs were modulated by the meanings of the sentences, i.e. MEPs recorded from hand and foot muscles were specifically modulated respectively by listening to hand and foot action-related sentences. In the behavioural experiment, participants were requested to respond with either a hand movement or a foot movement while listening to actions expressing either hand or foot actions. Buccino et al. (2005) report that reaction times for responses with the hand were slower during listening to hand action-related sentences, whereas reaction times for responses with the foot were slower while listening to foot action-related sentences. Both results can be interpreted as showing that motor execution and semantic processing of linguistically described actions compete for the same neural resources (see also Coello and Bidet-Ildei, this volume).

Using fMRI, Tettamanti et al. (2005) report that the left fronto-parieto-temporal network, which underlies the execution and the observation of (transitive) actions, was activated in a somatotopic fashion when participants respectively listened to sentences describing actions performed with the mouth, the hand and the leg. Aziz-Zadeh et al. (2006) also found that areas in the human premotor cortex (known to contain mirror neurons) were activated both when participants observed mouth, hand or foot actions performed by others and when they read phrases describing mouth, hand or foot actions (see also Aziz-Zadeh, this volume). Similarly, Hauk et al. (2004) compared brain areas active when participants performed tongue, finger and foot movements and when they silently read action words that described face, arm and leg movements (e.g. ‘lick’, ‘pick’ and ‘kick’). They report overlap between the brain areas active for the execution of actions and the processing of action verbs in accordance with the somatotopic representation of the bodily parts involved in both kinds of action. For example, the brain area activated by the presentation of a verb describing a hand action (e.g. ‘pick’) was reported by Pulvermüller et al. (2005) to overlap with that activated during execution of a hand action. (But see Postle et al., 2008, for a recent critical evaluation of the claims of congruent motor somatotopy of the representation of the meanings of action verbs.)

Boulenger et al. (2006) provide behavioural evidence for cross-talk (i.e. interference) between action word processing and overt motor performance. Participants were requested to manually reach a visual target: at the time of departure of the hand movement, participants were presented with a word (either an action verb or a concrete noun) on a screen. When the presented word was an action verb, not a concrete noun, the acceleration of the ongoing hand movement decreased. Furthermore, the interference between the hand action and the visual processing of the meaning of the action verb occurred within 200 ms after movement onset (see also Coello and Bidet-Ildei, this volume).

Using a masked priming paradigm, Boulenger et al. (2008a) provide additional behavioural evidence for the role of motor processing in semantic processing by investigating the effects of motor impairments in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) on their ability to process the meanings of action verbs. PD patients were requested to make a lexical decision for either action verbs or concrete nouns after being primed by the subliminal presentation of a masked word with the same meaning. They found priming effects for both concrete nouns and action verbs in healthy controls and PD patients on dopaminergic treatment for their motor disorders. However, they found priming effects only for concrete nouns, not for action verbs, when PD patients were off treatment (see also Coello and Bidet-Ildei, this volume; Taylor and Zwaan, this volume).

Boulenger et al. (2008b) provide still more evidence for the competition for the same neural resources between language processing and the planning and the execution of actions. While healthy participants were requested to produce a reaching arm movement, they were subliminally presented with either concrete nouns or action words during movement preparation. Using electroencephalography (EEG), Boulenger et al. (2008b) recorded the readiness potential (RP) correlate of movement preparatory processes prior to movement onset and they measured the kinematic features (wrist acceleration peak) of the subsequent execution of reaching movements. They report that, compared to the subliminal displays of concrete nouns, the subliminal displays of action verbs reduced the RP and decreased the amplitude of the wrist acceleration peak.

The basic question raised by these findings is whether motor processes and motor representations are constitutive of the meanings of action verbs or whether, as Mahon and Caramazza (2008: 60) put it on behalf of a ‘disembodied theory of concept representation’, ‘activation cascades from disembodied (i.e. abstract, amodal and arbitrary) concepts (of action) to the sensory and motor systems that interface with the conceptual system’. As Pulvermüller (2005: 579) recognizes, action word recognition could automatically and immediately trigger the activation of specific action-related networks. Or alternatively motor activation could be the consequence of a late, post-lexical strategy to imagine or plan an action (see also Coello and Bartolo, this volume).

As Jeannerod (2006) similarly recognizes, the fact that processing action words shares the same neural resources as planning and executing an action, in accordance with the somatotopic organization of the human motor system, cannot, in and of itself, show that the motor activation is intrinsically linked to (or constitutes) the meaning of action verbs. One possibility considered by Jeannerod (2006) is that processing and retrieving the meaning of an action verb could elicit a process of motor imagery that is known to involve the activity of the brain areas underlying the preparation and execution of the (described) action. As Jeannerod (2006: 162) puts it, on this interpretation, ‘motor simulation as in other types of motor images, would provide a pragmatic knowledge of the action, distinct from the semantic identification of the related action words’.8

As Frak et al. (2010) have further observed in the context of an experiment on the influence of the semantic processing of the meaning of an action verb upon grip force used in grasping, the observed motor activations could be interpreted as both ‘the spontaneous muscular facilitation evoked by the verb during lexical-semantic processing and as the incomplete inhibition of the motor output during simulation’. If so, then in agreement with Mahon and Caramazza’s (2008) interpretation of the above findings, the meanings of action words could be understood prior to the formation of a motor image of the described action and, therefore, independently of the activation of the brain areas involved in the preparation and execution of the described action.

Now in line with other experimental work showing that activation of selective brain areas (e.g. the amygdala or the intraparietal cortex) can be induced by the subliminal display of words of specific semantic categories (e.g. fearful words or number words), Boulenger et al. (2008b: 135) take their own findings to show that ‘subliminal displays of action words modulate cortical motor processes and affect overt motor behavior’. To rule out Jeannerod’s (2006) hypothesis, they assume that only if a word were consciously perceived then understanding its meaning triggers a process of motor imagery. They conclude that the subliminal display of action verbs cannot trigger motor imagery and further argue that ‘cortical structures that serve the preparation and execution of motor actions are essential for (i.e. constitutive of) the effective processing of action-related language’.

No doubt, more empirical work is needed in order to resolve this complex scientific issue. Nonetheless it is worth asking what it takes to grasp the concept expressed by an action verb or understand its meaning. Arguably, grasping the meaning of such English verbs as ‘grasping’, ‘licking’, ‘picking’ or ‘kicking’ might consist in entertaining a conceptual representation of the motor acts described by these words. The conceptual representation of such motor acts in turn might well consist in forming an abstract cross-modal (if not amodal) representation that brackets the difference between the purely motor representation underlying the execution of these acts and the various sensory (i.e. visual and acoustic) representations underlying the perceptual representations of these acts. On this assumption, one would expect that brain areas involved in the planning and execution of such motor acts should be part of the neural basis of the possession of the concepts of these acts. One would further expect that damage to the brain areas underlying the planning and execution of such motor acts might result in impairment in the neural basis of the mastery of such concepts—as revealed by the results of Boulenger et al.’s (2008a) experiment with PD patients off treatment.

Conversely, on this approach to the neural basis of the mastery of concepts of motor acts, one would also expect that impairments in the ability to understand the meanings of action words might be correlated with impairments in non-linguistic tasks of action understanding. Some evidence for this correlation is provided by the neuropsychological investigation of aphasic patients conducted by Saygin et al. (2005), showing that these brain-lesioned patients are not only impaired in processing the meanings of action words, but also in action–picture matching tasks. In the linguistic task, subjects were asked to fill in the missing complement of an action verb in an incomplete sentence. In the non-linguistic task, subjects were asked to select a picture of an object among a set of distracters to fit an incomplete picture displaying an action with a missing target. Saygin et al. (2005) report that aphasic patients performed poorly, not only in the linguistic task, but also in the non-linguistic task. These findings suggest that the brain lesion that produced the aphasic syndromes impaired the mastery of concepts of motor acts necessary not only to retrieve the meanings of action verbs, but also to grasp the non-linguistic content of pictorial representations of actions. This would be consistent with the classical non-embodied view of concepts as abstract and amodal representations of actions.

THE ROLE OF MIRROR NEURONS IN HUMAN VERBAL COMMUNICATION

Mirror neurons (MNs) were first discovered in the ventral premotor cortex of non-human primates: MNs are sensorimotor neurons that fire both in the brain of an agent that performs a transitive action and in the brain of the observer of an agent that performs the same kind of action. The activity of MNs has been interpreted in terms of the direct-matching model of action understanding. On this model, MN activity enables an observer to understand an agent’s action by directly mapping the agent’s observed movements on to the observer’s motor repertoire: ‘an action is understood when its observation causes the observer’s motor system to “resonate”’ (Rizzolatti et al., 2001: 661).

The direct-matching model of action understanding has been challenged by Csibra’s (2007) dilemma: both the agent’s overt act or movements and the agent’s goal are possible candidates for the direct-matching model of mirroring. As recognized by Rizzolatti and Sinigaglia (2010), at least among humans, an agent’s movements do not stand in a one-to-one relation to her goal: not only can an agent recruit different movements at the service of a single goal, but she can also put one and the same movement at the service of different goals. Consequently, if what is being mapped on to the observer’s motor repertoire by MN activity is the agent’s overt motor act (or bodily movements), then it is unlikely that mirroring could deliver a representation (or understanding) of the agent’s goal. Conversely, if the output of mirroring is a representation (or understanding) of the agent’s goal, then it is unlikely to be generated by the mapping of the agent’s observed movements on to the observer’s motor repertoire.

In response, Rizzolatti and Sinigaglia (2010) endorse the second horn of Csibra’s dilemma: on the basis of experimental results reported by Umiltà et al. (2008), they argue that, in the monkey brain, MN activity encodes goals. Umiltà et al. (2008) trained monkeys to grasp objects using both normal pliers and so-called ‘reverse’ pliers: grasping an object with normal pliers requires closing the fingers, but grasping with reverse pliers requires opening the fingers. Single cell recordings in area F5 in executive tasks by Umiltà et al. (2008) show that F5 neurons discharged during the same phase of grasping ‘regardless of whether this involved opening or closing of the hand’ (Rizzolatti and Sinigaglia, 2010: 266).9 In other words, what seems to matter to the firing of F5 neurons is the agent’s goal (grasping) irrespective of the difference between the agent’s closing and opening his fingers.

Furthermore, Rizzolatti and Sinigaglia (2010) also endorse a dual view of MN activity in human and non-human primates: whereas in non-human primates, only an agent’s goal can be mirrored, in humans both an agent’s goal and her movements can be mirrored by MN activity in an observer’s brain. As they put it:

in the earlier studies on the mirror mechanism, it was indeed not clearly specified that the parieto-frontal mirror mechanism in humans is involved in two kinds of sensory-motor transformation—one mapping the observed movements onto the observer’s own motor representation of those movements (movement mirroring), the other mapping the goal of the observed motor act onto the observer’s own motor representation of that motor act (goal mirroring).

(p. 269)

In a highly influential paper, Rizzolatti and Arbib (1998) have further proposed that:

the development of the human lateral speech circuit is a consequence of the fact that the precursor of Broca’s area was endowed, before speech appearance, with a mechanism for recognizing actions made by others. This mechanism was the neural prerequisite for the development of interindividual communication and finally of speech. We thus view language in a more general setting than one that sees speech as its complete basis.

(p. 190)

While Rizzolatti and Arbib (1998) assume that the main function of Broca’s area is to match action execution and action perception, Grodzinsky and Santi (2008) have recently argued that much neuropsychological evidence points towards two entirely different hypotheses about the main function of Broca’s area, one of which is that it serves syntactic complexity in general, and the other of which (favoured by Grodzinsky and Santi, 2008) is that it underlies computations dedicated to syntactic movement.

Now, in light of the distinction drawn in the second section of the present chapter, Rizzolatti and Arbib’s (1998) hypothesis about the mirroring function of Broca’s area can be given two different interpretations. The mirror mechanism that is taken to be the precursor of Broca’s area in humans can be conceived as the phylogenetic basis for either the human language faculty or the human mindreading ability to represent an agent’s communicative intention. As argued in the second section, one crucial property of the human language faculty is the recursivity of grammatical rules with the capacity to embed hierarchically organized phrases within phrases. The two options are distinct, since recursivity is a property of grammatical rules of natural languages and representing an agent’s communicative intention is required not only for human verbal communication, but also for human non-verbal communication, to succeed. Following Arbib (2005), several cognitive neuroscientists have explicitly explored the first option:

[we postulate] that the motor system is organized into neuronal chains, each coding a specific goal and combining different elements (motor acts) of the action. Further preliminary data on the monkey parietal and premotor cortex have shown that this type of organization is valid also for longer action sequences in which the same element of a chain is recursively involved in different steps of the sequence. Although this organization is certainly very basic, in terms of hierarchical arrangement, combinatorial power, achievement of meaning, and predictive value (i.e., every neuron coding a specific motor act of an action sequence facilitates predicting the outcome of that sequence) it has much in common with the syntactic structure of language. At present it is not clear how and whether this sequential motor organization could have been exploited for linguistic construction, but we can assume that, over the course of evolution, the more the motor system became capable of flexibly combining motor acts in order to generate a greater number of actions, the more it approximated a linguistic-like syntactic system.

(Fogassi and Ferrari, 2007: 140)

At this stage, as Fogassi and Ferrari’s (2007) quote recognizes, it is really an open question whether the mirror neuron system underlying the execution and the perception of action in non-human primates has the resources to give rise to the recursivity of the syntax of natural languages that is characteristic of the human language faculty.

However, there is another possible interpretation of Rizzolatti and Arbib’s (1998) hypothesis, in line with much work on MN activity since Gallese and Goldman’s (1998) classic paper: namely, that MN activity is the basis for the human mindreading ability to represent an agent’s intention. In particular, Iacoboni et al. (2005) have reported fMRI evidence that has been taken to show that MN activity enables an observer to represent an agent’s intention to drink. In the Context condition, participants saw only a teapot, teacups and food assembled as if either before or after tea. In the Action condition, they saw a human hand grasp a cup either with precision grip or with full prehension without any further contextual cues. In the Intention condition, they saw the same pair of hand actions within either the before-tea or the after-tea context. Since the Context condition contained no action, it served as a baseline. Iacoboni et al. (2005) report stronger activity for the fronto-parietal areas known to contain MNs in the Intention condition than in the Action condition. This suggests that MN activity recorded during the perception of an act of grasping a target can be modulated by the perception of further contextual cues.10

On the mirroring-first view of understanding another’s prior intention offered by Iacoboni et al. (2005: 539), these findings are taken to show that ‘premotor mirror neuron areas—areas active during the execution and the observation of an action—previously thought to be involved only in action recognition are actually also involved in understanding the intentions of others’. Thus, Iacoboni et al. (2005) speculate that MN activity enables an observer to discriminate two acts of grasping a cup, one of which is for the purpose of drinking from it, and the other of which is for the purpose of cleaning it. In effect, the mirroring-first view assumes that MN activity in an observer’s brain alone can take as input the perception of an agent’s act of grasping a target and generate as output a representation of the agent’s goal or intention, where the latter can be thought of as the agent’s prior intention to either drink a cup of tea or clean the cup.

There is, however, a rival interpretation of these findings according to which MN activity in the observer’s brain does not generate a representation of the agent’s goal or prior intention (to either drink from a cup or clean a cup) from the perception of the agent’s act of grasping a cup. Instead, MN activity results from an independent representation of the agent’s goal or prior intention (to either drink or clean a cup), which itself is based on the perceptual processing of contextual cues (see Csibra, 2007, and Jacob, 2008, 2009a, b). Unlike the mirroring-first view, this alternative interpretation of MN activity stresses the contribution of contextual cues to understanding another’s prior intention.11

Philosophers and psychologists (e.g. Searle, 1983 and Csibra, 2007) have drawn a two-pronged distinction between basic and non-basic actions and between motor intentions (or intentions in action) and prior intentions. For example, the non-basic action of turning the light on can be performed by executing several more basic actions (such as pressing an electrical switch or asking someone else to turn the light on). Similarly, an agent’s prior intention to turn the light on can be fulfilled by means of the fulfilment of several motor intentions (including the motor intention to press the electrical switch with her right index finger). In a couple of papers (Jacob and Jeannerod, 2005; Jacob, 2008), I have also argued for further distinguishing an agent’s non-social from an agent’s social prior intentions, where an agent’s social intentions are her intentions to affect a conspecific’s behaviour. Finally, some, but not all, of an agent’s social intentions are communicative intentions: in accordance with the Gricean tradition (see the second section of this chapter), I assume that an agent’s communicative intention can only be fulfilled if it is properly recognized by the addressee. For example, A’s intention that B believes that his wife is unfaithful to B is a social intention. But A’s intention counts as a communicative intention only if B acquires the belief that his wife is unfaithful to him as a result something A did together with B’s recognition that A intended him to acquire this belief.

An agent’s social intention, like his other prior intentions, stands to his motor intentions in a many–one relation. This is illustrated by the case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (from Stevenson’s novel). Dr Jekyll is a renowned surgeon who performs appendectomies on his anaesthetized patients. Mr Hyde is a dangerous sadist who performs exactly the same hand movements on his non-anaesthetized victims. It turns out that Mr Hyde is no other than Dr Jekyll. Dr Jekyll alias Mr Hyde may well execute twice the same motor sequence whereby he grasps his scalpel and applies it to the same bodily part of two different persons (one anaesthetized, the other suitably paralysed). If so, then Dr Jekyll’s motor intention will match Mr Hyde’s. Suppose that Dr Watson witnesses both Dr Jekyll’s and Mr Hyde’s actions. Upon perceiving Dr Jekyll, alias Mr Hyde, execute the same motor sequence twice, whereby he grasps his scalpel and applies it to the same bodily part of two different persons, presumably the very same MNs produce the same discharge in Dr Watson’s brain. However, Dr Jekyll’s social intention clearly differs from Mr Hyde’s: whereas the former intends to improve his patient’s medical condition, the latter intends to derive pleasure from his victim’s pain. The question is whether MN activity could enable Dr Watson to discriminate Dr Jekyll’s social intention from Mr Hyde’s (cf. Jacob and Jeannerod, 2005).

Becchio et al. (2008) report behavioural evidence relevant to this question. They compared three experimental conditions. In the single-agent condition, participants were asked to grasp an egg-shaped target located on a table 21 cm in front of them and to put it in a concave base located 28 cm to the right of the target’s initial position. In the social condition, participants were asked to grasp the same target at the same location and to pass it to a partner located to the participant’s right with his hand supine resting on the table 28 cm away from the target’s initial position. In the passive-observer condition, participants performed the action as in the single-agent condition in the presence of a passive observer seated at the far right of the table. After each trial, participants repositioned the target in its initial location. Becchio et al. (2008) measured four behavioural kinematic parameters: the length of the wrist pathway, the maximum trajectory height amplitude, the amplitude of the maximum wrist velocity and the time to peak velocity. They found that the social condition differed from both the single-agent and the passive-observer conditions along all four parameters: the length of wrist pathway and the maximum trajectory height amplitude were larger for the social condition than for the other two. The amplitude of the maximum wrist velocity and the time to peak velocity were smaller for the social condition than for the other two.

While this experiment shows the existence of kinematic differences between the execution of social and non-social tasks, it does not show that the kinematic differences between the social and the non-social tasks reflect the distinction between the agent’s social and non-social intentions. Arguably, the shape of a human hand (in the social condition) is perceptually more complex than that of an ovoid container. The kinematics of an agent’s transitive act might vary, not as a function of the agent’s social intention, but instead as a function of the perceptual complexity of the landing site of the agent’s hand action. If so, then application of Fitts’ law alone might account for the kinematic pattern of the participants’ hand actions. Furthermore, the experiment does not show that a human observer can pick up the kinematic differences between the agent’s actions in the social and non-social tasks—let alone via MN activity in an observer’s brain. In order to further test the impact of the contrast between an agent’s social and non-social intentions upon the kinematic profile of her hand action, it would be useful to compare the single-agent condition to a condition in which the agent would put the target in the same concave base hand-held by a human partner.

So far, the evidence does not show that MN activity could enable an observer to discriminate between Dr Jekyll’s and Mr Hyde’s respective social intentions. Now, consider the following instance of human non-verbal communication. Suppose Jill ostensively points her right index finger towards the wristwatch on her left wrist. (This is what Goldin-Meadow and Wagner (2005: 234) call ‘externalizing’ one’s thoughts.) Suppose further that she thereby makes manifest to Bob her communicative intention [that Bob believes [that she believes [that it is late]]]. If so, then the content of Jill’s communicative intention involves three levels of embedding (indicated by the brackets): it is a third-order metarepresentation. If now Bob comes to represent Jill’s communicative intention—if he ascribes it to Jill, then his own belief about Jill’s intention involves four levels of embedding and is, therefore, a fourth-order metarepresentation. The question is: could MN activity alone in Bob’s brain enable him to come to believe that Jill intends him to believe that she believes that it is late from the visual perception of Jill’s ostensive behaviour? Notice further that, by ostensively pointing her right index finger towards the wristwatch on her left wrist, Jill might also have conveyed an entirely different communicative intention, namely her intention that Bob believes that she believes that her wristwatch is not working. So far as I am aware, there is no evidence showing that MN activity alone could enable an addressee of a communicative act to select one of two competing communicative intentions an agent might have conveyed by means of a single piece of observable ostensive behaviour.12

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The goal of this chapter has been to review selected experimental evidence in favour of the symbol-grounding strategy characteristic of the embodied cognition (EC) research programme. As I argued in the first section, the symbol-grounding strategy amounts to the empiricist denial of any relevant distinction between conceptual and non-conceptual content. In the 1990s, the spectacular discovery of mirror neurons (MNs) showed that the same areas in the ventral premotor cortex of non-human primates are active during both the execution and the perception of transitive actions. In the next decade, the significance of the discovery of MN activity seemed confirmed and further extended by novel findings showing activities of the human motor and premotor cortices during language comprehension (i.e. understanding of the meanings of action verbs). These findings are indeed evidence of correlations between language understanding and motor activities, but they do not bear their interpretation on their sleeves. While the third section focused on the potential contribution of motor processes to the understanding of the meanings of action verbs, the fourth section focused on the potential contribution of MN activity to either the recursivity of the human language faculty or the human ability to represent an agent’s communicative intention. The take-home message of the third section is that, so far, the available evidence does not enable us yet to decisively rule out the possibility that the meanings of action verbs (or the concepts they express) are abstract contents of amodal symbols, i.e. neutral with respect to the sensory and motor differences between executing an action and observing the same action performed by another agent. The take-home message of the fourth section is that, so far, the empirical evidence does not support the hypothesis that MN activity (or the mirror system) could underlie either the recursivity of the human language faculty or the human ability to represent a speaker’s communicative intention.

NOTES

1 Only the third symbol-grounding strategy will be directly relevant to the rest of the present chapter.

2 Also see O’Regan’s (1992) claim that the world is an outside memory. Notice that this brand of anti-representationalism is slightly different from the eliminative materialist view espoused by P.M. Churchland (1981) and P.S. Churchland (1986), who recommend the elimination of propositional attitudes (e.g. beliefs and desires), not of all mental representations, from the vocabulary of neuroscientific explanations.

3 For a survey of experiments on change-blindness, see Simons and Rensink (2005).

4 Many philosophers (e.g. Dretske, 1978; Peacocke, 1998, 2001; Fodor, 2007) have argued for the distinction between the conceptual content of thoughts and beliefs and the non-conceptual content of perceptual experiences on the grounds that mastery of the concept of either the shape or colour of an object is neither necessary nor sufficient for a creature to enjoy a distinctive visual experience upon perceiving an object’s shape or colour. It is not necessary because there is something it is like to perceive, e.g. an octagonal object, whether or not one knows that what one is perceiving is an octagon. It is not sufficient because the finegrainedness of one’s ability to visually discriminate either the shape or the colour of an object far outstrips one’s ability to apply colour or shape concepts to the object.

5 There are non-grammatical limitations on the length of sentences, such as the fact that human life is finite and so are human attention and human memory.

6 Alternatively, if Bill were to combine Jill’s utterance with the contrary assumption that she enjoys rain (i.e. that if it is raining, then she is going out), then Bill could infer that Jill is going out.

7 See Jacob (2011) for further discussion.

8 As Frak et al. (2010) also put it, ‘the motor simulation thus provides the pragmatic knowledge congruent with the underlying action and complements the semantic recognition of the verb’.

9 Umiltà et al. (2008) report the results of single-cell recordings in area F5 mostly for executive tasks of grasping with normal and reverse pliers, but they also refer to ‘an example of F5 mirror neuron recorded during grasping with tools and during the observation of the same motor act’ (p. 2112), thereby offering evidence for mirroring of goals.

10 Using a similar experimental design and recording the activity of single cells in area IPL of macaque monkeys in both executive and observational tasks of grasping a target, Fogassi et al. (2005) report that distinct MNs respond to the execution/perception of a single act of grasping as a function of the next most likely act that the agent will perform.

11 The controversy between the two views is reminiscent of the controversy over whether motor activations are constitutive of one’s understanding of the meanings of action verbs or whether the former is a by-product of the latter (see the third section of this chapter).

12 In their recent review, Willems and Varley (2010) argue both that language and communication rely on distinct neural systems and that intention understanding recruits brain regions that extend beyond the mirror neuron system, including medial prefrontal areas and the temporo-parietal junction.

13 I am grateful to Yann Coello, not only for inviting me to a highly successful conference (held in Lille in early 2009) and then transforming it into a volume, but also for his critical comments on this chapter. I also acknowledge the comments of two anonymous referees. This work was supported by a grant from the French ministry of research (ANR-BLAN SOCODEV).

REFERENCES

Anderson, M.L. (2003). Embodied cognition: a field guide. Artificial Intelligence, 149: 91–130.

Arbib, M.A. (2005). From monkey-like action recognition to human language: an evolutionary framework for neurolinguistics. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28: 105–168.

Austin, J.L. (1962). How to do Things with Words. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Aziz-Zadeh, L., Wilson, S.M., Rizzolatti, G. and Iacoboni, M. (2006). Congruent embodied representations for visually presented actions and linguistic phrases describing actions. Current Biology, 16: 1–6.

Barsalou, L.W. (1999). Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22: 577–660.

Barsalou, L.W., Simmons, W.K., Barbey, A.K. and Wilson, C.D. (2003). Grounding conceptual knowledge in modality-specific systems. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(2): 84–91.

Becchio, C., Sartori, L., Bulgheroni, M. and Castiello, U. (2008). The case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde: a kinematic study of social intention. Consciousness and Cognition, 17: 557–564.

Boulenger, V., Roy, A.C., Paulignan, Y., Deprez, V., Jeannerod, M. and Nazir, T.A. (2006). Cross-talk between language processes and overt motor behavior in the first 200 ms of processing. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 18: 1607–1615.

Boulenger, V., Mechtouff, L., Thobois, S., Broussolle, E., Jeannerod, M. and Nazir, T. (2008a). Word processing in Parkinson’s disease is impaired for action verbs but not for concrete nouns. Neuropsychologia, 46(2): 743–756.

Boulenger, V., Silber, B.Y., Roy, A.C., Paulignan, Y., Jeannerod, M. and Nazir, T. (2008b). Subliminal display of action words interferes with motor planning: a combined EEG and kinematic study. Journal of Physiology, 102: 130–136.

Brooks, R. (1991). Intelligence without representation. Artificial Intelligence Journal, 47: 139–160.

Buccino, G., Riggio, L., Melli, G., Binkofski, F., Gallese, V. and Rizzolatti, G. (2005). Listening to action-related sentences modulates the activity of the motor system: a combined TMS and behavioral study. Cognitive Brain Research, 24: 355–363.

Carston, R. (2002). Thoughts and Utterances: The Pragmatics of Explicit Communication. Oxford: Blackwell.

Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic Structures. The Hague: Mouton.

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (2000). New Horizons in the Study of Language and Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Churchland, P.M. (1981). Eliminative materialism and the propositional attitudes, in Churchland, P.M. (1989), A Neurocomputational Perspective: The Nature of Mind and the Structure of Science. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Churchland, P.S. (1986). Neurophilosophy: Toward a Unified Science of the Mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Clark, A. (1997). Being There, Putting Brain, Body and World Together Again. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Clark, A. (2008a). Pressing the flesh: a tension in the study of the embodied, embedded mind. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 76: 37–57.

Clark, A. (2008b). Supersizing the Mind: Embodiment, Action, and Cognitive Extension. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clark, A. and Chalmers, D. (1998). The extended mind. Analysis, 58: 10–23.

Csibra, G. (2007). Action mirroring and action understanding, in Haggard, P., Rossetti, Y. and Kawato, M. (eds), Sensorimotor Foundations of Higher Cognition, Attention and Performance XXII. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Csibra, G. (2010). Recognizing communicative intentions in infancy. Mind and Language, 25(2): 141–168.

Dretske, F. (1978). Simple seeing, in Dretske, F. (2000), Perception, Knowledge and Belief. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fodor, J.A. (2007). The revenge of the given, in McLaughlin, B.P. and Cohen, J.D. (eds), Contemporary Debates in Philosophy of Mind. Blackwell: Oxford.

Fodor, J.A. (2009). Where is my mind? Times Literary Supplement, 31(3), 12 February.

Fogassi, L. and Ferrari, P.F. (2007). Mirror neurons and the evolution of embodied language. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(3): 136–141.

Fogassi, L., Ferrari, P.F., Gesierich, B., Rozzi, S., Chersi, F. and Rizzolatti, G. (2005). Parietal lobe: from action organisation to intention understanding. Science, 308: 662–67.

Frak, V., Nazir, T., Goyette, M., Cohen, H. and Jeannerod, M. (2010). Grip force is part of the semantic representation of manual action verbs. PLoS ONE, 5(3): e9728.

Gallagher, S. (2005). How the Body Shapes the Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gallese, V. (2008). Mirror neurons and the social nature of language: the neural exploitation hypothesis. Social Neuroscience, 3: 317–333.

Gallese, V. and Goldman, A. (1998). Mirror neurons and the simulation theory of mindreading. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12: 493–501.

Gallese, V. and Lakoff, G. (2005). The brain’s concepts: the role of sensory-motor system in reason and language. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 22: 455–479.

Glenberg, A.M. and Kaschak, M.P. (2002). Grounding language in action. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 9(3): 558–565.

Goldin-Meadow, S. (1999). The role of gesture in communication and thinking. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 3(11): 419–429.

Goldin-Meadow, S. and Wagner, S.M. (2005). How our hands help us learn. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(5): 234–241.

Goldman, A. and de Vignemont, F. (2009). Is social cognition embodied? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(4): 154–159.

Grice, H.P. (1957). Meaning, in Grice, H.P. (1989), Studies in the Way of Words (pp. 212–223). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Grice, H.P. (1967/1975). Logic and conversation, in Grice, H.P. (1989), Studies in the Way of Words (pp. 22–40). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Grice, H.P. (1968). Utterer’s meaning, sentence meaning and word meaning, in Grice, H.P. (1989), Studies in the Way of Words (pp. 117–137). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Grice, H.P. (1969). Utterer’s meaning and intentions, in Grice, H.P. (1989), Studies in the Way of Words (pp. 86–116). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Grodzinsky, Y. and Santi, A. (2008). The battle for Broca’s region. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(12): 474–480.

Haugeland, J. (1998). Mind embodied and embedded, in Haugeland, J. (1998), Having Thought: Essays in the Metaphysics of Mind (pp. 207–240). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hauk, O., Johnsrude, I. and Pulvermüller, F. (2004). Somatotopic representation of action words in human motor and premotor cortex. Neuron, 41: 301–307.

Hauser, M.D., Chomsky, N. and Fitch, W.T. (2002). The faculty of language: what is it, who has it, and how did it evolve? Science, 298: 1569–1579.

Iacoboni, M., Molnar-Szakacs, I., Gallese, V., Buccino, G., Mazziotta, J.C. and Rizzolatti, G. (2005). Grasping the intentions of others with one’s own mirror neuron system. PLoS Biology, 3: 529–535.

Jacob, P. (2008). What do mirror neurons contribute to human social cognition? Mind and Language, 23(2): 190–223.

Jacob, P. (2009a). The tuning-fork model of social cognition. Consciousness and Cognition, 18: 229–243.

Jacob, P. (2009b). A philosopher’s reflections on mirror neurons. Topics in Cognitive Science, 1(3): 570–595.

Jacob, P. (2011). Meaning, intentionality and communication, in Maienborn, C., von Heusinger, K. and Portner, P. (eds), Semantics: An International Handbook of Natural Language Meaning (pp. 11–25). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Jacob, P. and Jeannerod, M. (2005). The motor theory of social cognition: a critique. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(1): 21–25.

Jeannerod, M. (2001). Neural simulation of action: a unifying mechanism for motor cognition. NeuroImage, 14: S103–S109.

Jeannerod, M. (2006). Motor Cognition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Liberman, A.M. and Mattingly, I.G. (1985). The motor theory of speech perception revised. Cognition, 21: 1–36.

McDowell, J. (1994). Mind and the World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Mahon, B.Z. and Caramazza, A. (2008). A critical look at the embodied cognition hypothesis and a new proposal for grounding conceptual content. Journal of Physiology, 102: 59–70.

Noë, A. (2004). Action in Perception. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

O’Regan, J.K. (1992). Solving the ‘real’ mysteries of visual perception: the world as an outside memory. Canadian Journal of Psychology/Revue Canadienne de Psychologie, 46(3): 461–488.

O’Regan, J.K. and Noë, A. (2001). A sensorimotor approach to vision and visual consciousness. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24(5): 939–973.

Peacocke, C. (1998). Nonconceptual content defended. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 58: 381–388.

Peacocke, C. (2001). Does perception have nonconceptual content. The Journal of Philosophy, 98: 239–264.

Postle, N., McMahon, K.L., Ashton, R., Meredith, M. and de Zubicaray, G.I. (2008). Action word meaning representation in cytoarchitectonically defined primary and premotor cortices. NeuroImage, 43: 634–644.

Prinz, J.J. (2002). Furnishing the Mind: Concepts and their Perceptual Basis. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Prinz, J.J. (2008). Is consciousness embodied?, in Robbins, P. and. Aydede, M. (eds), Cambridge Handbook of Situated Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pulvermüller, F. (2005). Brain mechanisms linking language and action. Nature Review Neuroscience, 6: 576–582.

Pulvermüller, F., Hauk, O., Nikulin, V.V. and Ilmoniemi, R.J. (2005). Functional interaction of language and action: a TMS study. European Journal of Neuroscience, 21: 793–797.

Recanati, F. (2004). Literal Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rizzolatti, G. and Arbib, M.A. (1998). Language within our grasp. Trends in Neurosciences, 21: 188–194.

Rizzolatti, G. and Craighero, L. (2004). The mirror-neuron system. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 27: 169–192.

Rizzolatti, G. and Sinigaglia, C. (2010). The functional role of the parieto-frontal mirror circuit: interpretations and misinterpretations. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(4): 264–274.

Rizzolatti, G., Fogassi, L. and Gallese, V. (2001). Neurophysiological mechanisms underlying the understanding and imitation of action. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2: 661–670.

Saygin, A.P., Wilson, S.M., Dronkers, N.F. and Bates, E. (2005). Action comprehension in aphasia: linguistic and non-linguistic deficits and their lesion correlates. Neuropsychologia, 42: 1788–2004.

Searle, J. (1980). Minds, brains, and programs. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3: 417–458.

Searle, J. (1983). Intentionality: An Essay in the Philosophy of Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Searle, J. (1985). Minds, Brains and Science. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Searle, J. (1992). The Rediscovery of the Mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Shapiro, L. (2007). The embodied cognition research programme. Philosophy Compass, 2(2): 338–346.

Simons, D.J. and Rensink, R.A. (2005). Change blindness: past, present, and future. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(1): 16–20.

Sperber, D. and Wilson, D. (1986). Relevance, Communication and Cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tettamanti, M., Buccino, G., Saccuman, M.C., Gallese, V., Danna, M., Scifo, P., Fazio, F., Rizzolatti, G., Cappa, S.F. and Perani, D. (2005). Listening to action-related sentences activates fronto-parietal motor circuits. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 17: 273–281.

Umiltà, M.A., Escola, L., Intskirveli, I., Grammont, F., Rochat, M., Caruana, F., Jezzini, A., Gallese, V. and Rizzolatti, G. (2008). When pliers become fingers in the monkey motor system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(6): 2209–2213.

Willems, R.M. and Varley, R.A. (2010). Neural insights into the relation between language and communication. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 4(203): 1–8.

Wilson, M. (2002). Six views of embodied cognition. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 9(4): 625–636.