Children’s use of spatial reference frames in verbal and non-verbal tasks

INTRODUCTION

When trying to understand a verbal description of a spatial configuration, a listener or reader normally goes beyond the information given, and forms an elaborate mental model in which various attributes of the described scene are inferred (Struiksma et al., 2009; see also Taylor and Zwaan, this volume). When parsing a spatial description and forming a mental model, one always needs to choose a reference frame (RF), which denotes the point of view that is taken when perceiving spatial relations (see also Miller and Carlson, this volume). The observer can choose his or her own viewpoint, take that of an object that is part of the scene, or take one that relies on omnipresent cardinal directions or local/distal landmarks. Depending on the frame of reference, the representations and descriptions of spatial relations within and between objects differ. In the spatial literature two particular RFs are generally dissociated: the egocentric RF in which locations of objects are represented with respect to the observer; and an allocentric RF in which locations of objects are represented within an external framework (i.e. configuration of landmarks). In the language literature other taxonomies have been used to denote linguistic RFs, i.e. viewer-centred, object-centred or environment-centred RFs (see Miller and Johnson-Laird, 1976). In this chapter we use the terms intrinsic, relative and absolute RFs as proposed by Levinson (1996, 2003). A relative RF defines the relations among objects with respect to the observer’s position. Note, however, that the relative spatial location of (an) object(s) change(s) when the observer changes his or her position. Consequently, the use of a relative RF may create ambiguity. The intrinsic RF takes the perspective of one of the objects in the spatial scene, labelled the ‘ground object’ and relates the locations of other objects (‘figures’) to it. For this RF the location of the observer is irrelevant and the definition of a spatial relation does not change when the observer moves. Finally, the absolute RF uses a fixed point of view that is located on an invariable axis, such as the cardinal axes. Since the application of this frame to a scene remains unaltered upon the rotation of either the observer or the object(s), it is essential to be aware of its orientation when perceiving or describing a spatial configuration.

An interesting question arises as to how, which and under what conditions these spatial and linguistic RFs are employed. Regarding the ‘how’ question, consensus seems to exist about the way spatial and linguistic RFs are activated for use: when a spatial scene is presented, all relevant RFs are automatically activated and one frame is selected for the response (Carlson-Radvansky and Logan, 1997; Taylor et al., 1999; see also Miller and Carlson, this volume). However, in the literature there is still ongoing debate about the ‘which’ and ‘under what conditions’ questions. Therefore, in the present study we were specifically interested in these questions, not only from an adult perspective, but also from a developmental perspective. In the following paragraphs we will discuss what is known about this topic from the adult literature.

Starting with the ‘which’ question, previous research suggests that the use of a specific RF could be predicted on the basis of one’s native language. Levinson (2003) conducted an experiment in which adult Dutch and Tzeltal speakers were asked to reconstruct a spatial scene of several objects after having been rotated. Based on the observed response patterns, participants’ RF use could be revealed. It was demonstrated that choice of RF largely corresponded to the RF conventionally employed in the native language: Dutch speakers preferred a relative (egocentric) RF, whereas Tzeltal speakers showed a preference for the absolute (allocentric) RF. This finding did not show that participants were incapable of understanding different conceptualizations of space; it suggested that they had interpreted the test situation in a way that was most plausible given their linguistic conventions (Newcombe and Huttenlocher, 2003). Provided that speakers of English and Dutch, among many other languages, habitually use both relative and intrinsic RFs when communicating spatial relations, they often face ambiguity. For example, the term ‘left of’ in the sentence ‘the bone is left of the tiger’ can denote ‘left’ with respect to the observer (relative RF) or ‘left’ with respect to the tiger, the ground object (intrinsic RF). This confronts speakers and listeners with a dilemma. So, ‘which’ of these RFs do we select, and ‘under what condition’ do we do so?

Many studies have attempted to identify the factors that determine the selection of a frame of reference. Some state that RF selection depends on situational factors (e.g. objects’ characteristics, the functional relation between objects, the purpose of the task, and the perspective taken on the scene), and it requires cognitive flexibility to switch between RFs depending on these factors (Carlson-Radvansky and Irwin, 1993; Carlson-Radvansky and Logan, 1997). Others suggest the existence of a generally preferred, or ‘default’ RF (Taylor and Rapp, 2004; Taylor et al., 1999). Evidence for the favoured use of an intrinsic RF in a verbal task comes from a study with adults by Taylor and colleagues (Taylor and Rapp, 2004). Participants viewed spatial scenes with two objects, of which one always had intrinsic sides (e.g. a chair) and the other had the shape of a doughnut (technically a ‘torus’). Upon the presentation of a spatial description involving these objects, participants were to decide whether it matched the configuration depicted. The majority of the participants spontaneously applied the intrinsic RF (Taylor and Rapp, 2004). Although the authors of the study did not provide an explanation for this finding, favoured use of an intrinsic RF makes sense in the light of cooperative communication. Adult speakers and listeners understand that ambiguity is a problem in spatial reference, and will opt for the reference frame that is the least ambiguous, i.e. a non-egocentric one (Grice, 1975; Newcombe and Huttenlocher, 2003). The fact that an ‘intrinsic RF preference’ was not found on a non-verbal task in which spatial RFs were required (see study of Levinson, 2003, described above) might be in line with the hypothesis that RF preference is task dependent. In a verbal communicative task, adults tend to use a non-egocentric (e.g. intrinsic) RF for politeness reasons, whereas in a non-verbal task they prefer the use of an egocentric (e.g. relative) RF, possibly for the reason that this allows them to economize on cognitive effort (Keysar et al., 1998).

Regarding the RF applied in a verbal task, an obvious, and open, question would be if, and at what age, children prefer the use of an intrinsic RF? Put differently, do children have, and if so at what age, the spatial knowledge, the linguistic skills and the ‘social understanding’ for effective spatial communication? From earlier studies we know that, by 6 years, children have sufficient spatial knowledge and linguistic skills for effective communication; however, what supposedly develops during mid-childhood is the ability to understand listener needs (Newcombe and Huttenlocher, 2003). We aim to determine the age at which this latter ability develops, by studying the appearance of an intrinsic RF preference in a verbal task. In addition, to make sure this is not a generally preferred (or default) RF in children, we present children with a non-verbal control task similar to the one used by Levinson (2003). We expect (Dutch) children who share the same linguistic conventions as (Dutch) adults to show a preference for the relative RF in this latter task. To also test participants’ cognitive flexibility, an ‘intrinsic’ condition was included in which a cue was provided that was expected to make the intrinsic RF more salient. Accordingly, two tasks (in one test occasion) were assessed: one in which linguistic RFs were required (‘sentence–picture matching task’), and one in which spatial RFs were required (‘spatial reconstruction after rotation task’). Dutch children between 5 and 12 years of age and adults were tested on both tasks, first to examine the development of the application of RFs in a verbal task, possibly teaching us something about children’s ability to take into account listeners’ needs (by applying an intrinsic RF), and, second, to see whether this ability is not task dependent.

METHOD

Participants

Twenty-eight adults (number of females = 16; mean age = 19.89; SD = 1.87) and 113 children participated in the study. The children comprised four age groups: 5–6 years (n = 28, number of girls = 12; mean age = 5.54; SD = 0.51), 7–8 years (n = 29, number of girls = 10; mean age = 7.48; SD = 0.51), 9–10 years (n = 31, number of girls = 16; mean age = 9.58; SD = 0.50), and 11–12 years (n = 25, number of girls = 14; mean age = 11.72; SD = 0.54). The adults were students at Utrecht University, who gave their written consent and received a small payment. The children’s parents gave consent for their child’s participation in the study. All participants reported to be healthy, were native speakers of Dutch, and were unaware of the purpose of the study.

Sentence–picture matching task

The first experimental task comprised 52 stimuli that were presented in random order on a computer touch screen. Each stimulus consisted of an auditorily presented sentence (i.e. ‘the bone is left of the tiger’) and three pictures (standardized for brightness) that were presented at the same time. The set of pictures for each trial always contained one picture that depicted the verbal description from a relative perspective, one picture that depicted the verbal description from an intrinsic perspective, and one picture in which the objects mentioned in the verbal description were presented but in a constellation that did not match either perspective. The pictures were always presented with two pictures at the top of the computer screen, and one picture at the bottom (see Figure 9.1). However, the position of each type of picture (i.e. matching the relative RF, the intrinsic RF or none of both RFs) was determined randomly. Participants were instructed to select the picture that was described by the sentence, by touching the picture on the screen. They were told to do so instantaneously in order to ensure that a response would reflect their spontaneous choice rather than a conscious selection between the two possible correct responses. Responses were registered automatically. The stimuli included equal numbers of ‘in front of’, ‘behind’, and ‘to the left/right of’ relationships between animate and inanimate objects, of which the ground object always possessed intrinsic sides. The ground object of (at least) the pictures (that correctly depicted the sentence) always faced the same side, in order to make sure participants did not use different strategies for towards/away and left/right object-facing directions (Taylor and Rapp, 2004). The test trials were preceded by three practice trials, one of each type (behind, front and left/right). Participants did not receive feedback on their responses.

Figure 9.1 Two stimuli examples of the verbal (‘sentence–picture matching’) task, each consisting of three pictures with two pictures presented at the top of the computer screen, and one picture at the bottom. Each stimulus (i.e. set of pictures) contained one picture that depicted the verbal description from a relative perspective (left stimulus example: bottom picture; right stimulus example: upper left picture), one picture that depicted the verbal description from an intrinsic perspective (left stimulus example: upper left picture; right stimulus example: upper right picture), and one picture in which the objects were presented in a constellation that did not match either perspective (left stimulus example: upper right picture; right stimulus example: bottom picture).

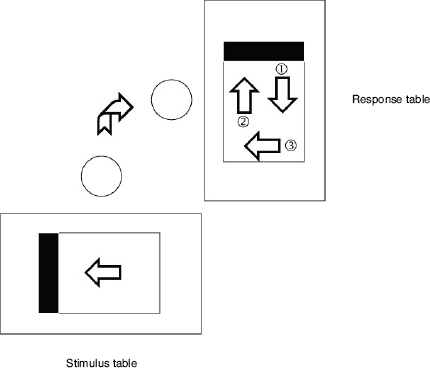

Spatial reconstruction after rotation task

In the second task, participants’ spontaneous use of spatial RF was assessed. The task was adapted from Levinson (2003). Two tables (stimulus and response table) with identical boards were placed at 90° relative to each other (see Figure 9.2). The boards had a coloured stripe (i.e. an intrinsic marker) on one of the surface sides. On the first two trials, both boards were placed with the unmarked side facing up, so that no salient intrinsic markers were present. On the third trial, the marker was visible. To prevent a confounding effect by drawing attention to the procedure of changing the sides of the boards between the second and third trial, the boards were replaced after each trial. During each of the three trials, the experimenter put three small toy animals in a predetermined order on one of the boards. Participants were asked to sit on a chair facing one of the tables (i.e. the stimulus table) and to remember the arrangement of the toy animals on the board so that they could reconstruct the scene on the response table. Before reconstruction participants were rotated 90° with the chair so that they faced the response table. The assignment of either ‘stimulus’ or ‘response’ to the tables was counterbalanced within and between subjects. Different responses to the task were possible: a response was classified as relative when the participant placed the toy animals facing (i.e. left or right) the same way with respect to him- or herself; intrinsic when the participant placed the toy animals with respect to either the ‘insides’ of the tables (i.e. where the tables ‘met’) or the ‘outsides’, thus facing the left side of the response table if they had faced the right side of the stimulus table, and vice versa; absolute when the participant placed the toy animals in the same direction in absolute space, i.e. north, south etc. During testing, participants’ reconstructions of the animal configurations were written down by the experimenter. In order to pronounce the intrinsic sides of the scenes, on the third trial the marked sides of the boards were facing up. NB: When the marked side of the board on the stimulus table would be on the participant’s right side, it would appear on his or her left side on the response table and vice versa.

Figure 9.2 Experimental set-up of the non-verbal (‘spatial reconstruction after rotation’) task, adapted from Levinson (2003). Two tables (stimulus and response table) with identical boards were placed at 90° relative to each other. The boards had a coloured stripe (i.e. an intrinsic marker) on one of the surface sides. Different responses to the task were possible: a response was classified as relative when the participant placed the toy animals facing (i.e. left or right) the same way with respect to him- or herself (arrow 1 in the Figure); intrinsic when the participant placed the toy animals with respect to either the ‘insides’ of the tables (i.e. where the tables ‘met’) or the ‘outsides’, thus facing the left side of the response table if they had faced the right side of the stimulus table, and vice versa (arrow 2 in the Figure); absolute when the participant placed the toy animals in the same direction in absolute space, i.e. north, south etc. (arrow 3 in the Figure).

RESULTS

Sentence–picture matching task

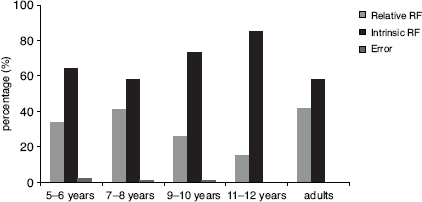

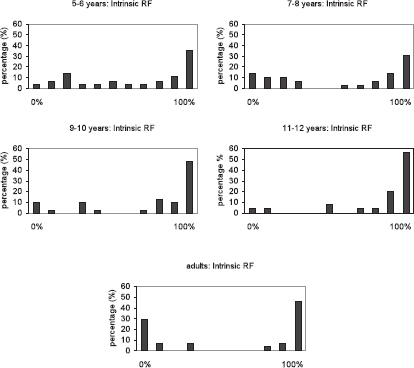

Figure 9.3 presents the mean percentages of relative RF responses, intrinsic RF responses and errors made on the ‘sentence–picture matching’ task for each age group separately. The percentage of children and adults employing an intrinsic RF was high in all age groups: 64 per cent of the 5–6 year-olds; 58 per cent of the 7–8 year-olds, 73 per cent of the 9–10 year-olds, 85 per cent of the 11–12 year-olds, and 58 per cent of adults. However, from this figure it cannot be derived whether children switched between the use of different RFs between trials. For this reason, we have depicted the consistency of participants’ RF use in Figure 9.4, with from the left to the right 0 to 100 per cent intrinsic RF use, i.e. 0 per cent intrinsic RF use means 100 per cent relative RF use. As shown in this figure, within each age group most participants used a 100 per cent intrinsic RF strategy, whereas fewer used a 100 per cent relative RF strategy. Interestingly, the consistency with which participants employed either of both RFs seems to develop with age: young children switched more between the RFs than older children and adults did. Statistically, though, the response patterns did not differ between the age groups.

Figure 9.3 Mean percentages of relative RF responses, intrinsic RF responses and errors made on the ‘sentence–picture matching’ task for each age group separately.

Figure 9.4 The consistency of participants’ RF use with from left to right 0 to 100 per cent intrinsic RF use, i.e. 0 per cent intrinsic RF use means 100 per cent relative RF use.

Spatial reconstruction after rotation task

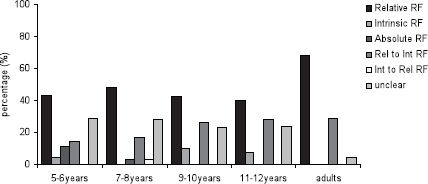

Figure 9.5 presents the data across the three trials. Different response patterns were possible: (1) participants could use a relative RF on all three trials; (2) participants could use an intrinsic RF on all three trials; (3) participants could use an absolute RF on all three trials; (4) after the introduction of the intrinsic marker participants switched from the use of a relative RF to the use of an intrinsic RF; (5) after the introduction of the intrinsic marker participants switched from the use of an intrinsic RF to the use of a relative RF; (6) participants switched between RFs already at the first two trials, not showing a preference for the use of either RF (called ‘unclear’ in the figure). The percentages of children who spontaneously used either one of these response patterns are shown for each age group separately. Again, the age groups did not differ significantly from each other in overall RF use on this task, i.e. the percentage of children and adults employing a relative RF was high in all age groups. In addition, it was shown that, with the introduction of the intrinsic marker, in each age group a given percentage of participants (around 20–30 per cent) switched from the use of a relative RF to the use of an intrinsic RF (option 4, as described above). This means that already at a young age participants were cognitively flexible.

Figure 9.5 Percentage of participants showing certain response patterns across the three trials: (1) participants could use a relative RF on all three trials; (2) participants could use an intrinsic RF on all three trials; (3) participants could use an absolute RF on all three trials; (4) after the introduction of the intrinsic marker participants switched from the use of a relative RF to the use of an intrinsic RF; (5) after the introduction of the intrinsic marker participants switched from the use of an intrinsic RF to the use of a relative RF; (6) participants switched between RFs already at the first two trials, not showing a preference for the use of either RF (‘unclear’ in the figure).

DISCUSSION

The present study investigated choice of RF in participants of various age groups in different experimental settings. Dutch children between 5 and 12 years of age and adults were tested on a task in which linguistic RFs were required (‘sentence–picture matching task’), and on a task in which spatial RFs were required (‘spatial reconstruction after rotation task’). In the first task we examined children’s ability to take into account listeners’ needs, and the second task served the purpose of a control task to see whether this ability is not task dependent. Given that previous research showed that RF selection depends largely on situational factors (e.g. task purpose), we expected the verbal and the non-verbal task to elicit different RF preferences at least for adults, and possibly also for children.

Studies with adult participants showed a favoured use of an intrinsic RF in verbal situations (Taylor and Rapp, 2004; Taylor et al., 1999), and a relative RF preference on a non-verbal task (Levinson, 2003). To start with the intrinsic RF preference on verbal tasks, adults seem to use a non-egocentric RF since they are aware of the fact that ambiguity is a problem (Newcombe and Huttenlocher, 2003), thus they do so to sort (more) effective communication. We were interested to see at what age this so-called ‘social understanding’ or ‘the ability to understand listener needs’ would appear. The children and adults were confronted with an auditorily presented sentence and three pictures on a computer screen, and subsequently were asked to select the picture that was described by the sentence. The results showed that the age groups did not differ from each other in overall response pattern, i.e. the intrinsic RF was preferred over the relative RF by all age groups. This finding might suggest that already from a young age (i.e. at least from 5 years onwards) children use a non-egocentric RF for effective communication. Provided that participants were instructed to select a picture instantaneously indicates that this ability might, at least to some extent, be automated. It should be noted, however, that the task included relatively simple verbal descriptions. Therefore it should be interesting to extend these findings to more complex verbal descriptions, e.g. the verbal description of a route. In addition to overall preference we looked into the consistency of RF use over trials, i.e. we examined whether children and adults switched between the use of different RFs between trials. As shown in Figure 9.3, within each age group most participants used a 100 peer cent intrinsic RF strategy. However, interestingly, the consistency with which participants employed either of both RFs develops with age: young children switched more between the RFs than older children and adults. The finding that adults respond consistently and economically by applying the same RF on all trials of a task is in line with previous research (Carlson, 1999; Carlson-Radvansky and Jiang, 1998). To our knowledge, this is the first study that shows a developmental trend.

To make sure that the overall intrinsic RF preference on a verbal task at already an early age does not merely represent a generally preferred (or ‘default’) RF in young children (Taylor and Rapp, 2004; Taylor et al., 1999), we tested all age groups on a spatial RF task that would almost certainly result in the opposite pattern, i.e. an overall relative RF preference. Since children (at least from 5 years onwards) and adults share the same linguistic conventions, we expected them to perform comparably on the ‘Levinson task’ (2003). This task was previously shown to be capable of predicting RF use on the basis of one’s native language, and had resulted in Dutch speakers preferring a relative RF. The children and adults in our study were confronted with a spatial array consisting of three toy animals placed on a board. After a rotation of 90°, participants were asked to reconstruct the scene on a different board. Based on the response pattern of the participant, it could be decided what RF he or she had used. As expected, overall, all age groups preferred the use of a relative RF. Besides the finding that adults’ performance is in concurrence with the adult data obtained in the study of Levinson (2003), children’s preference for a relative (i.e. egocentric) RF confirms earlier results of studies investigating spatial RF preferences in young children (Bullens et al., 2010; Nardini et al., 2006; Nardini et al., 2009; Newcombe and Huttenlocher, 2003). This means that, indeed, RF selection depends on situational factors (Carlson-Radvansky and Irwin, 1993; Carlson-Radvansky and Logan, 1997), and that the preferred use of an intrinsic RF in a verbal task is inherent to its nature.

Additional evidence for RF selection depending on situational factors comes from our finding that the introduction of an intrinsic marker in the nonverbal task just described made participants switch RFs: after the introduction of the intrinsic marker, about 20 to 30 per cent of the participants in each age group switched from relative RF to intrinsic RF, whereas the opposite pattern (i.e. from intrinsic RF to relative RF) was (almost) never observed. This strongly supported the idea that, already from a young age, children possess the cognitive flexibility to change RF depending on situational factors. In all, we showed that, at the age of 5 years, like older children and adults, children use a non-egocentric (e.g. intrinsic) RF for politeness reasons, whereas they prefer the use of an egocentric (e.g. relative) RF in a non-verbal situation. Although the verbal task included relatively simple verbal descriptions, these findings indicate that, at this age, children already have sufficient spatial knowledge, linguistic skills and understanding of listener needs, all of which are necessary for effective communication. New challenges lie in designing similar (and possibly more complex) (non-)verbal tasks on which even younger children can be tested in order to more thoroughly determine the (transitional) age at which children learn to take into account listeners’ needs.

It should be noted here that the ultimate goal of spatial communication and the subsequent construction of cognitive representations is to guide a listener’s actions. That is, it may instruct the addressee to pick up a specific object and move it to a new location; it may help in searching for a certain target; and it may be used for planning and carrying out sequences of manoeuvres. We may speculate that this action focus has been a prime driving force for the evolution of the human spatial communication system. In line with this, various studies have implied that the choice of reference frame in spatial descriptions appears to depend on functional action relations. Carlson-Radvansky and Radvansky (1996) demonstrated that intrinsic reference frames were preferred in describing a visual scene with a mail carrier and a mailbox when the mail carrier was facing the mailbox, whereas a relative frame was more often selected when the mail carrier was facing the other way and the functional action relationship had disappeared (see also Coventry and Garrod, 2004; Miller and Carlson, this volume). Future studies may address how far young children are already sensitive to the observed action influences in their spatial communications or whether they have to learn this on the basis of experienced communication failures.

REFERENCES

Bullens, J., Igloi, K., Berthoz, A., Postma, A. and Rondi-Reig, L. (2010). Developmental time course of the acquisition of sequential egocentric and allocentric navigation strategies. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 107: 337–350.

Carlson, L.A. (1999). Selecting a reference frame. Spatial Cognition and Computation, 1(4): 365–379.

Carlson-Radvansky, L.A. and Irwin, D.E. (1993). Frames of reference in vision and language: Where is above? Cognition, 46: 223–244.

Carlson-Radvansky, L.A. and Jiang, Y. (1998). Inhibition accompanies reference-frame selection. Psychological Science, 9(5): 386–391. Carlson-Radvansky, L.A. and Logan, G.D. (1997). The influence of reference frames selection on spatial template construction. Journal of Memory and Language, 37: 441–437.

Carlson-Radvansky, L.A. and Radvansky, G.A. (1996). The influence of functional relations on spatial term selection. Psychological Science, 7(1): 56–60. Coventry, K.R. and Garrod, S.C. (2004). Saying, Seeing and Acting: The Psychological Semantics of Spatial Prepositions. Hove and New York: Psychology Press.

Grice, H.P. (1975). Logic and conversation, in Cole, P. and Morgan, J.L. (eds), Syntax and Semantics, 3: Speech Acts (pp. 41–58). New York: Academic Press.

Keysar, B., Barr, D.J. and Horton, W.J. (1998). The egocentric basis of language use: insights from a processing approach. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 7(2): 46–50.

Levinson, S.C. (1996). Frames of reference and Molyneux’s question: crosslinguistic evidence, in Bloom, P., Peterson, M.A., Nadel, L. and Garrett, M.F. (eds), Language and Space (pp. 3–36). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Levinson, S.C. (2003). Space in Language and Cognition: Explorations in Cognitive Diversity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Miller, G.A. and Johnson-Laird, P.N. (1976). Language and Perception. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nardini, M., Burgess, N., Breckenridge, K. and Atkinson, J. (2006). Differential developmental trajectories for egocentric, environmental and intrinsic frames of reference in spatial memory. Cognition, 101: 153–172.

Nardini, M., Thomas, R.L., Knowland, V.C.P. and Braddick, O. (2009). A viewpoint-independent process for spatial reorientation. Cognition, 112: 241–248.

Newcombe, N.S. and Huttenlocher, J. (2003). Making Space: The Development of Spatial Representation and Reasoning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Struiksma, M.E., Noordzij, M. and Postma, A. (2009). What is the link between language and spatial mages? Behavioral and neural findings in blind and sighted individuals. Acta Psychologica, 32: 145–156.

Taylor, H.A. and Rapp, D.N. (2004). Where is the donut? Factors influencing spatial reference frame use. Cognitive Processing, 5: 175–188.

Taylor, H.A., Naylor, S.J., Faust, R.R. and Holcomb, P.J. (1999). ‘Could you hand me those keys on the right?’ Disentangling spatial reference frames using different methodologies. Spatial Cognition and Computation, 1: 381–397.