Functional effects in spatial language

INTRODUCTION

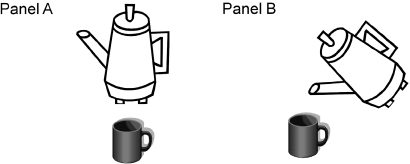

Imagine sitting down to breakfast at a friend’s place, and having them approach the table, coffee pot in hand, asking whether you want a cup. When you sleepily respond that you do, your friend tells you to “place your cup below the pot.” In an utterance such as this, the object whose location is specified (e.g., the cup) is referred to as the located object and the object used to describe its location (e.g., the pot) is referred to as the reference object (Hayward and Tarr, 1995; Landau and Jackendoff, 1993; Talmy, 1983). In order to interpret this utterance and decide where to place your cup, you must map the spatial term “below” to a suitable region of space around the pot (Logan and Sadler, 1996; Miller and Johnson-Laird, 1976). Generally, spatial terms such as “below” have been defined based on their geometric properties (Landau and Jackendoff, 1993; Logan and Sadler, 1996; Talmy, 1983), including center of mass (Gapp, 1995; Regier and Carlson, 2001). In the current example, the most appropriate geometric definition for “below” corresponds to a location below a bounding box drawn around the reference object, with the best location being geometrically centered (often referred to as “on-axis”), as shown in Panel A of Figure 10.1. However, research in spatial language has shown that the functional properties of the objects in addition to these geometric properties influence your interpretation of these types of descriptions (Carlson-Radvansky and Tang, 2000; Carlson-Radvansky et al., 1999; Coventry, 1998, 1999; Coventry and Garrod, 2004; Coventry et al., 2001; Miller et al., 2011; Ullmer-Ehrich, 1982; see also Coello and Bidet-Ildei, this volume; Coventry, this volume; Miller and Carlson, this volume). For example, knowing how cups and pots typically interact might lead you to prefer an interpretation of “below” that places the cup in the location shown in Panel B of Figure 10.1. This spatial configuration is consistent with one’s understanding that the goal of the interaction between these two objects is to transfer coffee from the pot to the cup, and this placement accordingly enables the flow of coffee to be directed toward the cup. Note that the functional placement in Panel B is still within the geometric “below” region, but shifted away from the geometrically defined best placement (often referred to as “off-axis”). This suggests that functional effects may act by re-prioritizing preferences for the different subregions of this “below” space.

Figure 10.1 Placements of a cup below a coffee pot. Panel A shows a geometric placement such that the cup is directly below the geometric center of the coffee pot. Panel B shows a functional placement such that the cup is directly below the actively functional part of the coffee pot (the spout) rather than the geometric center.

Interestingly, the influence of such functional and interactive features on the interpretation of spatial descriptions does not entirely depend upon the objects being semantically related or typically associated, as with coffee pots and cups in Figure 10.1. In fact, functional interactions between two unrelated objects may be encouraged by their spatial arrangement.

Consider Figure 10.2. Panel A shows a hammer and a nail, and the presumed interaction between the two objects is clear, based not only on their typical functional association, but also on the way in which they are spatially arranged and oriented—the hammer will clearly be used to strike the head of the nail. Panel B shows this same interactive pounding relationship between the hammer and a less typically associated object (banana). One can easily envision an interaction that will result in a mashed banana, even though these objects are not typically used together. Moreover, holding the objects constant but changing the spatial configuration (Panel C), one can highlight a different type of interaction between the hammer and the banana, one in which the hammer is used to peel the banana. Therefore, a functional interaction between two objects may be derived from the spatial configuration of the objects, and does not strictly depend upon their semantic association (Carlson and Kenny, 2006). Understanding the nature of these types of functional effects and interactions as well as how they influence a given interpretation of a spatial description will thus involve some computation of their semantic association, their spatial configuration, and their ability to interact.

Figure 10.2 Various placements of a hammer relative to a nail or banana. Panel A illustrates a typical relationship between two functionally related objects. Panel B illustrates a similar functional relationship between two objects that have no semantic relationship but can interact in a manner similar to that of the hammer and the nail. Panel C illustrates that by changing the spatial relationship between the hammer and the banana in Panel B, a new interactive relationship between two objects can be formed on the basis of their spatial properties. Namely, the hammer might be used to peel the banana.

The goal of the current chapter is to present a structured account of the way in which functional features affect spatial language by focusing on three important aspects of the functional influence. First, we define the scope of these functional effects, asking under what circumstances they influence spatial language. Second, we examine a possible mechanism that may give rise to these functional effects during the interpretation of spatial descriptions. Finally, we explore the locus of these functional effects, asking which processes are influenced during the apprehension of a spatial description. A central conclusion of this chapter is that the understanding of an object’s function may influence the apprehension of spatial descriptions, but this is not obligatory, and depends instead on the spatial configuration of the objects, as suggested in the opening examples. The focus on scope, mechanism and process offers a set of limits that will be helpful for embodied cognition accounts that strive to accommodate such functional effects.

SCOPE

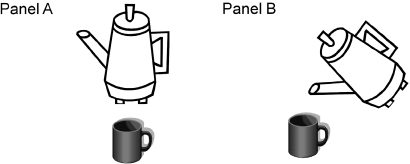

Functional features are components of objects that are linked to particular parts. For example, a pencil has a graphite tip used for writing and a rubber eraser used for erasing. Lin and Murphy (1997) show that the functionally important parts of an object are critical for their recognition and classification. Specifically, they had participants learn new objects, and highlighted particular parts in their descriptions of their function. They found that participants were more likely to categorize new items that possessed this functional part as tokens of this type of object, and were faster at perceiving that these functional parts were missing in a missing-part detection task. Given such a prioritization of functional features, Carlson-Radvansky et al. (1999) asked whether such functionally important parts of an object might influence the way in which spatial descriptions involving these objects are interpreted. For example, consider the piggy bank in Figure 10.3, with a coin slot as an important functional part. Carlson-Radvansky et al. (1999) hypothesized that the interpretation of a spatial instruction such as “Place the coin above the piggy bank” would be influenced by the knowledge that the slot is a functionally important part of the piggy bank, such that placements of the coin above the slot would be biased toward the functional part. This is illustrated by the arrow in Panel A.

In contrast, a geometric view would predict placements above the geometric center of the object, as illustrated by the arrow in Panel B (Gapp, 1995). In the task, participants were shown pictures of objects such as the piggy bank in which the functional part was offset from the geometric center of the object, and asked to place a located object above or below the reference object. There was no mention of the functional part. Moreover, two types of located objects were used: objects that typically interacted with the functional part of the reference object, such as a coin, and objects that did not typically interact with the functional part of the reference object, but could potentially interact in the same manner, such as a ring placed in the bank for safe-keeping. The dependent measure was the deviation of the placement of the located object relative to the center of mass of the reference object. If subjects interpreted the spatial term “above” with respect to the geometric features, placements should cluster around the center of mass, with a random distribution on either side. However, if subjects interpreted the spatial term with respect not only to geometry, but also with respect to the functional interaction between the objects, then placements should be biased away from the center, in the direction of the functional part. The results showed a strong and significant bias toward the functional part, with this effect strongest when the located object was typically related rather than atypically related, suggesting an additional contribution of the semantic association of the objects. This work is consistent with other work in the literature showing that the function of an object may influence one’s interpretation of space around that object (Carlson-Radvansky and Radvansky, 1996; Carlson-Radvansky and Tang, 2000; Coventry, 1998; Coventry et al.,

Figure 10.3 Examples of stimuli used in Carlson-Radvansky et al. (1999). Participants were instructed to “Place the coin above the piggy bank.” Placements that were clustered around a key functional part (the slot, see Panel A) were considered to be based on a functional definition of “above.” Placements of the coin that were clustered around the geometric center of a bounding box around the piggy bank (see Panel B) were considered to be based on a geometric definition of “above.”

One open question from the Carlson-Radvansky et al. (1999) study was whether subjects were indeed thinking of the functional parts of the reference objects. In the task instructions, there was no mention of the function of the object, and the results only really indicate that there was a bias to a given prominent part of the object (indeed, the one picked by experimenters). To assess whether this part was tied to the function of the object (as opposed to being preferred simply because of its size or location on the object), we asked a new group of subjects to segment the set of 16 reference objects into as many parts as they wished, and provided labels for the parts. For example, a toothbrush might be segmented into the brush, the neck, and the handle. Parts that were selected by the majority of participants were given to a new set of participants in a new task in which they were asked to assess function and typicality. Specifically, subjects were divided into one of three groups based on the set of materials that they were to judge: (1) reference objects alone; (2) reference objects with their atypical objects; and (3) reference objects with their typical objects. In the “reference object alone” group, subjects were asked to select the part of the reference object that was most functional for fulfilling an object’s interaction. In the “reference object with atypical/typical” groups, subjects were asked to select the part of the reference object that was most important for fulfilling the interaction between the two objects. In all three conditions, subjects selected the part deemed most functional by Carlson-Radvansky et al. (1999) at a rate that was significantly above chance, suggesting that participants in the spatial description study were sensitive to the function of this designated part, and that this biased their interpretation of the space around the object. There was also variability in functional strength, such that the functional part was selected most often with the typical object (88 percent), less often with the atypical object (69 percent), and least often when the reference object was alone (58 percent). These results support the idea that participants in the original Carlson-Radvansky et al. (1999) study were biased to interpret a spatial description relative to a given part of the reference object due to its functional importance.

Carlson and Kenny (2006) investigated three possible explanations of the functional effects observed by Carlson-Radvansky et al. (1999). First, functional effects may be driven by the prominence of the functional part of the object. Here, the interactive relationship between the two objects is not of principle interest; rather, a bias toward the functional part will always be observed because that part is most prominent. This is consistent with the finding in the follow-up study of selection of the functional part significantly above chance levels in all three conditions. This account also predicts that this prominent part is fixed, and that all located objects will be biased toward this given part. Second, functional effects may be a product of the typicality of the semantic association between parts and objects, such as the coin and the piggy bank versus the ring and the piggy bank. This is consistent with the finding in the follow-up study of stronger functional effects for the typical located objects than the atypical located objects. This account also predicts that when the located objects are changed, so that they typically interact with a different part of the object, the functional bias will be centered on that semantically associated part. Finally, functional effects may be grounded in an understanding of how the objects and their parts interact. That is, there is a semantic association between the located and reference objects, such that there is a bias to place the objects close to the parts with which they are semantically associated. However, according to this third account, this will only be observed when the objects can be placed in a manner that enables them to interact.

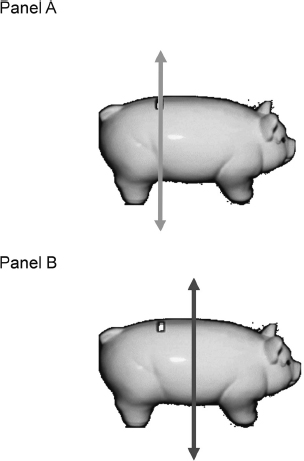

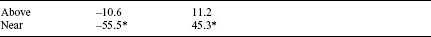

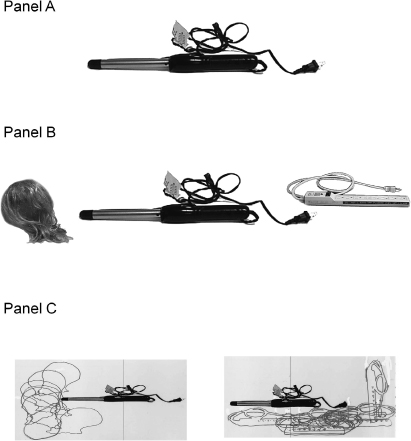

In order to address these possibilities, Carlson and Kenny (2006) had participants place a located object in some spatial relation to a reference object. The reference objects each had two distinct functional parts, located on different sides of the object. An example is shown in Panel A of Figure 10.4, which depicts a curling iron and its two functional parts: the iron and the plug. For each reference object, two located objects were selected, with each semantically associated with one of the functional parts, as illustrated by the wig and power strip in Panel B. Note that the direction of interaction between these objects and the reference object is from the side. The final key manipulation was of the spatial term used in the placement instruction, which could have been “near” or “above.” Spatial terms such as “near” convey proximity but not direction, and so allow a placement of one object at any point around the reference object, provided that it is at a relatively close distance (for work on the factors that influence this distance, see Carlson and Covey, 2005 and Morrow and Clark, 1988). Carlson and Kenny (2006) predicted that placements of the located objects would be biased toward their respective functional parts on these trials. As shown in Table 10.1 as well as Panel C of Figure 10.4, the data show strong functional placements for the spatial term “near.” In contrast, spatial terms such as “above” convey direction but not proximity, and so constrain the set of placements in the space around the reference object. Note that this subset of “above” placements does not enable an interaction between the located objects and the reference object, because these objects interact from the side. Thus, Carlson and Kenny (2006) predicted that, even though the same semantic association held between the objects, the placements would now be geometrically determined, because the constraints of the spatial term prohibited a placement that enabled the functional interaction to take place. The data also supported this prediction, as shown in Table 10.1 by the lack of functional effects in the placements for “above.”

Table 10.1

Percentage deviations from geometric center for functional object one (F1) and functional object two (F2) for the terms “above” and “near.” The asterisk indicates that the deviations are significantly biased toward the appropriate functional part for the term “near” but not for the term “above.”

Figure 10.4 Panel A shows an example of an object with two functional parts; here, the iron and the plug for a curling iron. Panel B shows two objects that could interact with the functional parts of the curling iron. Here a wig could interact with the iron and a power strip could interact with the plug. Panel C shows the placements of the wig and the power strip when subjects were asked to place each object “near” the curling iron.

This divergence indicates that interactive features are dependent not only on the semantic association of the objects, but also on the spatial features that may enable the interaction to take place. That is, spatial features seem to act as a gatekeeper for the effect of functional features; they must enable the interaction to be fulfilled in order for functional features to influence spatial language. As such, the scope of the functional influence of objects on spatial language is more complex than a simple semantic and functional association between objects, and is integrally tied to the spatial configuration in which the objects are embedded.

MECHANISM

A formal mechanism that may give rise to these types of functional effects is provided by the attention vector sum model (AVS; Regier and Carlson, 2001; see also Carlson et al., 2006). Originally, AVS was conceptualized as a means of defining spatial terms in a geometric fashion. In AVS, a spatial term such as “above” or “below” is defined by a vector sum weighted by attention (Figure 10.5). As shown in Figure 10.5a, an attentional beam is focused on a reference object at the point closest to the located object, extending out to encompass the located object. The direction of the located object relative to the reference object is computed from a set of vectors that are rooted at all points within the reference object, pointing up to the located object; sample vectors are shown in (b). Figure 10.5c illustrates the idea that the vectors are weighted by the amount of attention that is allocated to their roots, illustrated by the length of the vectors. Figure 10.5d shows that these weighted vectors are summed to produce a vector that corresponds to the overall direction of the target relative to the reference object. As shown in (e), this overall direction is then compared to a reference orientation (in this case, upright vertical because the spatial term is above). The greater the deviation of the overall direction from this reference orientation, the lower the acceptability of the spatial term as a description of the spatial relation between the two objects. This model does well in accounting for much of the empirical data concerning the influence of geometric features on spatial language; however, the original version of AVS was not designed to accommodate extra-geometric features such as function (Coventry and Garrod, 2004).

Carlson et al. (2006) show that a simple modification to AVS enables the model to accommodate both geometric and functional features and their influences on the interpretation of spatial language. Specifically, the model includes a parameter that modulates the amount of attention that is paid to a given part of an object, depending upon its functional status. For example, in Figure 10.5f, the outlined part of the rectangle is taken to be a functional part, and the weights assigned to the vectors rooted in these parts are adjusted, as reflected by their longer length. This translates to an interpretation of “above” that is a product of both function and attention, resulting in a shift of the interpretation of “above” toward the functional part of the reference object.

Figure 10.5 The attention vector sum model (AVS). (a) shows an attentional beam focused on a reference object closest to the located object, represented by the dot. (b) shows vectors rooted at various points in the reference object aimed toward the located object. (c) shows that these vectors are weighted by the amount of attention present at their root. (d) shows the result of the summation of the vectors; the overall direction of the target relative to the reference object. (e) shows the deviation of the location of the located object relative to the interpretation of a spatial term, in this case “above.” (f) shows a reference object with a functional part (outlined in bold). Here vector direction is determined both by function and attention.

The success of the functional version of AVS to accommodate geometric and functional effects (for details, see Carlson et al., 2006) suggests that attention may be one mechanism that can be used to express the functional effects. More generally, this modification to AVS argues that the traditional view of spatial language must be augmented such that it can account for not only information about what or where objects are but also how the processes of spatial language are linked to more general cognitive processes.

This idea that language processes may be grounded in more general cognitive processes is largely consistent with embodied approaches to spatial language (Glenberg and Kaschak, 2002; Zwaan, 2004). Indeed, the functional effects discussed thus far are consistent with embodied approaches to spatial language (Barsolou, 1999; Glenberg, 1997; Glenberg and Kaschak, 2002; Zwaan, 2004) that argue that language comprehension may involve a dynamic mental representation (see also Coello and Bidet-Ildei, this volume; Coventry, this volume). For example, Zwaan (2004) presents a framework in which language can be viewed as a set of cues that activate mental simulation of described events (see also Velay and Longcamp, this volume). Consequently, the description “The cup is below the coffee pot” may activate a mental representation of the typical interaction of a cup and a coffee pot that subsequently restricts the interpretation of “below” to an area underneath the coffee pot that more readily fulfills that functional relationship than the strictly geometric definition of “below.” Similar theories concerning the influence of conceptual structure on spatial language have argued that language is understood in terms of action (Glenberg and Kaschak, 2002) and that function is a complex relational concept that can lead to different senses of function (Barsalou, 1999).

LOCUS

Thus far, we have focused exclusively on the influence of functional features on the interpretation of a spatial term. The current section explores the possibility that the influence of functional properties affects not only the processes critical to the comprehension of a spatial description, but also those in the production of a spatial description (see also Coello and Bidet-Ildei, this volume; Coventry, this volume). Producing a spatial description involves not only the apprehension of a spatial term that relates the two objects, but also the selection of an appropriate reference object from which to spatially relate the located object. Given that objects are embedded in scenes that typically contain numerous surrounding candidate reference objects, an important issue is defining the dimensions upon which a reference object is selected. These could be spatial (Hayward and Tarr, 1995; Hund and Plumert, 2007; Logan and Sadler, 1996), perceptual (de Vega et al., 2002; Miller and Johnson-Laird, 1976; Talmy, 1983), or functional (Carlson and Kenny, 2006; Carlson et al., 2006; Carlson-Radvansky et al., 1999; Coventry, 1999; Coventry and Garrod, 2004). Indeed, Miller et al. (2011) showed that spatial features of an object are prioritized during reference-object selection, with objects placed on-axis with the located object preferred to objects placed off-axis.

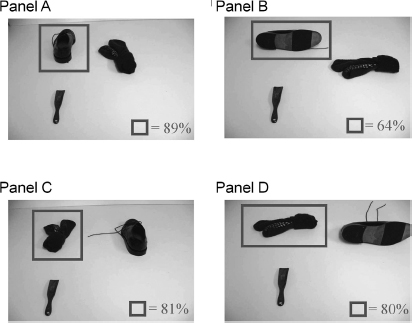

To assess whether functional features may also influence reference object selection, Miller et al. (2011) created displays, such as those shown in Figure 10.6, containing a located object (shoehorn) and two candidate reference objects (shoe and sock) that were matched in overall size and shape. Of the two candidate reference objects, one interacted in a typical manner with the located object (shoe and shoehorn) and one did not interact typically (sock and shoehorn). Across displays, they manipulated whether the typically interacting object occurred on-axis (Panels A and B) or off-axis (Panels C and D). In addition, across displays they manipulated whether the candidate reference objects were oriented in a manner to interact with the located objects (Panels A and C) or did not enable an interaction (Panels B and D). Subjects were asked to select the reference object that was “by” the located object by completing the frame “The located object is by the_____________.”

The data on the displays in Figure 10.6 show the percentage of participants selecting the on-axis object (outlined with a box) as the reference object. There are two primary effects of interest. First, the reference object that is on-axis should be selected more frequently than the reference object that is off-axis (Logan and Sadler, 1996). Indeed, subjects were much more likely to select the on-axis object across all conditions (78 percent), underscoring the importance of spatial features in reference-object selection. Second, any functional effects should only be observed when the functional object is on-axis. This follows the reasoning of Carlson and Kenny (2006) that the spatial term must allow the interaction to occur in order for functional effects to be observed. In support of this prediction, when the functional object was on-axis relative and positioned interactively relative to the located object (Panel A) it was very likely to be selected (89 percent) as compared to when it was on-axis but positioned non-interactively (Panel B, 64 percent).

Moreover, this effect was eliminated when both objects were off-axis (Panels C and D), indicating that the functional effects would only be observed when the spatial features enabled the interaction. This effect replicates the findings observed by Carlson and Kenny (2006) on the interpretation of a spatial term, and extends them to a new locus—that of selecting a reference object. Overall, the influence of functional features on spatial language seems to be inextricably linked to the concept of space itself such that spatial language or spatial features enable the influence of functional features.

Figure 10.6 Examples of the stimuli used in Miller et al. (2011). Panel A shows the functionally related object (shoe) positioned interactively and on-axis relative to the located object (shoehorn). Panel B shows the shoe positioned non-interactively and on-axis relative to the shoehorn. Panel C shows the shoe positioned interactively and off-axis relative to the shoehorn. Panel D shows the shoe positioned non-interactively and off-axis relative to the shoehorn.

This idea that the interpretation of functional features depends on both knowledge of the objects involved, and an understanding of the relations between objects, suggests that functional features can be defined in terms of their interactivity, which depends in turn on spatial features. In other words, unless the spatial layout of a scene, or the spatial term used to describe a scene, supports an interactive relationship, then functional features have difficulty strongly influencing spatial language. This is consistent with the idea that the function of an object or the interaction between two functionally related objects is not automatically activated (Bub et al., 2003), but is dependent on a situation model that suggests an interaction between two functionally related objects. Specifically, we argue that, when people want to spatially relate two objects, they consider two pieces of information in tandem: (1) how the objects interact with one another based on experience and action; and (2) whether the spatial term constraints or spatial layout constraints enable such an interaction.

The purpose of this chapter was to investigate the scope, mechanism, and locus of the functional effects observed during the apprehension of spatial descriptions. With respect to scope, functional features influence spatial language most strongly when an interactive relationship between objects exists and is fulfilled (Carlson and Kenny, 2006). With respect to mechanism, AVS provides a plausible account of the role of attention in the expression of these functional effects, grounding these linguistic processes in more general cognitive processes, a theme consistent with the central tenet of this volume. With respect to locus, the influence of functional features is found in at least two of the processes that are critical to the apprehension of spatial descriptions—the selection of a reference object and the interpretation of a spatial term.

Theoretically, the results discussed in this chapter are consistent with the idea that, when people spatially relate two objects, they consider both how the objects interact with one another and the spatial properties of the objects or term. That is, when people are engaged in a spatial task they actively consider how they interact with said objects based on experience, which is consistent with embodied approaches to spatial language (Glenberg and Kaschak, 2002; Zwaan, 2004). Importantly, we maintain that spatial features are essential and primary for spatial language interpretation, but that functional information about an object is active and used in certain cases depending on context. Overall, this account points to an emphasis on interpreting spatial language within a framework of action that considers experience, goals, and context.

REFERENCES

Barsalou, L.W. (1999). Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22(4): 577–660.

Bub, D.N., Masson, M.E.J., and Bukach, C.M. (2003). Gesturing and naming. Psychological Science, 14(5): 467.

Carlson, L.A. and Covey, E.S. (2005). How far is near? Inferring distance from spatial descriptions. Language and Cognitive Processes, 20: 617–632.

Carlson, L.A. and Kenny, R. (2006). Interpreting spatial terms involves simulating interactions. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 13: 682–688.

Carlson, L.A., Regier, T., Lopez, W., and Corrigan, B. (2006). Attention unites form and function in spatial language. Spatial Cognition and Computation, 6(4): 295–308.

Carlson-Radvansky, L.A. and Radvansky, G.A. (1996). The influence of functional relations on spatial term selection. Psychological Science, 7(1): 56–60.

Carlson-Radvansky, L.A. and Tang, Z. (2000). Functional influences on orienting a reference frame. Memory and Cognition, 28(5): 812–820.

Carlson-Radvansky, L.A., Covey, E.S., and Lattanzi, K.M. (1999). “What” effects on “Where”: functional influences on spatial relations. Psychological Science, 10(6): 516.

Coventry, K.R. (1998). Spatial prepositions, functional relations, and lexical specification, in Olivier, P. and Gapp, K.P. (eds), Representation and Processing of Spatial Expressions (pp. 247–62). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Coventry, K.R. (1999). Function, geometry and spatial prepositions: three experiments. Spatial Cognition and Computation, 1(2): 145–154.

Coventry, K.R. and Garrod, S.C. (2004). Saying, Seeing and Acting: The Psychological Semantics of Spatial Prepositions. Hove: Psychology Press.

Coventry, K.R., Prat-Sala, M., and Richards, L. (2001). The interplay between geometry and function in the comprehension of over, under, above, and below. Journal of Memory and Language, 44(3): 376–398.

de Vega, M., Rodrigo, M.J., Ato, M., Dehn, D.M., and Barquero, B. (2002). How nouns and prepositions fit together: an exploration of the semantics of locative sentences. Discourse Processes, 34: 117–143.

Gapp, K.P. (1995). Basic meanings of spatial relations: computation and evaluation in 3d space. Proceedings of the National Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Seattle, WA: 1393–1398.

Glenberg, A.M. (1997). What memory is for: creating meaning in the service of action. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 20(1): 41–50.

Glenberg, A.M. and Kaschak, M.P. (2002). Grounding language in action. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 9(3): 558.

Hayward, W.G. and Tarr, M.J. (1995). Spatial language and spatial representation. Cognition, 55: 39–84.

Hund, A.H. and Plumert, J.M. (2007). What count as by? Young children’s use of relative distance to judge nearbyness. Developmental Psychology, 43(1): 121–133.

Landau, B. and Jackendoff, R. (1993). Whence and whither in spatial language and spatial cognition? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 16(2): 255–265.

Lin, E.L. and Murphy, G.L. (1997). Effects of background knowledge on object categorization and part detection. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 23: 1153–1169.

Logan, G.D. and Sadler, D.D. (1996). A computational analysis of the apprehension of spatial relations, in Bloom, P., Peterson, M.A., Nadel, L., and Garrett, M.F. (eds), Language and Space (pp. 493–530). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Miller, G.A. and Johnson-Laird, P.N. (1976). Language and Perception. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Miller, J.E., Carlson, L.A., and Hill, P.L. (2011). Selecting a reference object. Journal of Experiment Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition, 37(4): 840–850.

Morrow, D.G. and Clark, H.H. (1988). Interpreting words in spatial descriptions. Language and Cognitive Processes, 3: 275–291.

Regier, T. and Carlson, L.A. (2001). Grounding spatial language in perception: an empirical and computational investigation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130(2): 273–298.

Talmy, L. (1983). How language structures space, in Pick, H.L. and Acredolo, L.P. (eds), Spatial Orientation: Theory, Research, and Application (pp. 225–282). New York: Plenum.

Ullmer-Ehrich, V. (1982). The structure of living space descriptions, in Jarvella, R.J. and Klein, W. (eds), Speech, Place and Action (pp. 219–249). Chichester: Wiley.

Zwaan, R.A. (2004). The immersed experiencer: toward an embodied theory of language comprehension, in Ross, B.H. (ed.), The Psychology of Learning and Motivation: Advances in Research and Theory (Vol. 44, pp. 35–62). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.