The spatial mapping of numbers: Its origin and flexibility

From looking at price tags to pressing elevator buttons, we interact with number symbols on a regular basis throughout our daily lives, making directional movements towards them and experiencing spatial consequences as a result. Pervasive and systematic biases in our spatial behaviour towards numbers have received much attention in the recent literature: small numbers (such as 1 or 2) are usually associated with left space and larger numbers (such as 8 or 9) with right space, and this population stereotype leads to attentional, manual, oculo-motor and decision biases (for reviews see Fias and Fischer, 2005; de Hevia et al., 2008; Wood et al., 2008; see also Ishihara et al., this volume).

The association between space and number magnitude is in the literature referred to as SNARC (for Spatial-Numerical Association of Response Codes). It is typically assessed in the parity task, by measuring how fast participants classify single digits as odd or even with horizontally separated button responses. Equally many small versus large and odd versus even digits are presented at a central fixation point; the response rule is changed half way through the data-collection process (either ‘respond with the left button to even numbers’ or ‘respond with the right button to even numbers’). Decision speed and accuracy are recorded on a computer. The difference between the average duration of a right-button response and the average duration of a left-button response is calculated separately for each digit. This computation usually results in positive values (i.e., faster left-button responses) for the smaller digits and in negative values (i.e., faster right-button responses) for the larger digits (see also Ishihara et al., this volume). Regressing these difference scores against digit magnitudes then yields a negative regression slope for most participants. Although the fit of this linear approximation (expressed as the amount of variance accounted for) may vary considerably across participants, this slope coefficient is a convenient summary of the direction and strength of each individual’s spatial-numerical association or SNARC. The average slope across a group of participants is usually reliably smaller than zero, with typical values around –5 ms/digit (see Wood et al., 2008, for a comparison of effect sizes across different tasks and a discussion of inter-individual variability). A similar bias in accuracy rates rules out an interpretation of the SNARC effect in terms of a speed-accuracy trade-off.

Where does the SNARC come from? In neuroscientific terms, there is considerable overlap between cortical areas for numerical cognition and for spatial processing, in particular along the intraparietal sulci (Hubbard et al., 2005). In functional terms, the association is usually accounted for by referring to the notion of a spatially directed ‘mental number line’. According to this hypothesis, participants have previously acquired a spatial association for numbers that leads to spontaneous activation of the concept ‘left’ whenever small magnitudes are processed, and to spontaneous activation of the concept ‘right’ for larger magnitudes. In other words, the SNARC effect is interpreted as reflecting the congruency between lateralized button presses and the spatial arrangement of magnitudes in the observer’s mind. This is, however, a mere re-description of the results because no systematic manipulation of the hypothesized spatial-numerical experiences has occurred in most of the published experiments. In the absence of systematic manipulations of the strength of SNARC, we are left to wonder what processes underlie SNARC, how it developed and how persistent it might be. These are important questions, especially in the light of recent evidence suggesting that SNARC extends from single-digit processing into the realm of mental arithmetic, with addition inducing right biases and subtraction inducing left biases (Pinhas and Fischer, 2008; Knops et al., 2009). A better understanding of the origin of SNARC may thus have both theoretical and practical implications.

This chapter reviews three possible accounts for the origin of SNARC. The first section discusses the influence of reading habits and documents the considerable flexibility of SNARC even during reading. These observations suggest that, contrary to the received view, spatially directional scanning is only a relatively minor contributor to SNARC. In the second section, a review of recent developmental studies of SNARC in pre-schoolers helps to identify other sources of SNARC. One candidate source is the universal habit of finger counting, a behaviour that is probably acquired through observational learning. The third section picks up this idea and reports new studies that begin to systematically manipulate spatial-numerical experiences in adults to better understand the mechanisms and thus the possible origins of SNARC. From this work it appears that observational learning is indeed a strong candidate in our search for origins of the pervasive association between numbers and space. The concluding section of this chapter places SNARC in the broader theoretical context of embodied cognition. In this view, sensory and motor experiences (such as directional scanning and finger counting) become part of our conceptual knowledge about number magnitudes. Documenting embodiment effects in the domain of numerical representations provides an important challenge to classical accounts of knowledge representation.

READING HABITS AND SNARC

One often-cited view is that SNARC reflects a population stereotype acquired through reading and/or writing habits. According to this view, small numbers are associated with left space because people in Western cultures start reading or writing on the left side of a page and also start counting with small numbers. The habit of interacting with written symbols and their associated concepts through spatially directional scanning might therefore ‘spill over’ and generalize from words to numbers, for example through directional counting habits: just as we tend to begin reading on the left side of a page, we tend to begin counting objects from left to right (see next section for evidence). Over time, this consistent sensory-motor association between small numbers and left space becomes part of the meaning of small number names and is then reactivated whenever we deal with small magnitudes, either directly or indirectly, in the form of digit symbols or number words. As a consequence, adults tend to look to the left when thinking about smaller numbers and to the right when thinking about larger numbers (Loetscher et al., 2010). Similarly, small numbers become associated with small grip apertures while large numbers become associated with wider grip apertures (Andres et al., 2008), suggesting that the magnitude meaning of a symbol reactivates the motor behaviour performed during actual interaction with physical magnitudes, such as small/light vs. large/heavy objects.

The notion that spatially directional visuo-motor activities might contribute to, and eventually shape, our conceptual representations has gained credibility in recent years within the theoretical framework of ‘embodied cognition’ (for recent reviews, see Barsalou, 2008; Fischer and Zwaan, 2008). This notion is hard to align with more traditional theories of human cognition as symbol manipulation, according to which meaning is represented abstractly and independently of the modality-specific sensory or motor activities that occurred during concept acquisition. Number meaning, in particular, has long been considered as a domain of abstract symbolic representation par excellence, with mental arithmetic as a prototypical instance of amodal symbol manipulation (e.g., Groen and Parkman, 1972). Therefore, it is theoretically important to clarify the possible influence of spatially directional reading habits on numerical representation and processing.

What do empirical studies of SNARC tell us about the influence of reading habits on the spatial content of number concepts in particular, and about the embodied nature of concepts in general? As a first step towards an answer, let’s look at the specificity of the influence from directional reading on to numerical cognition. If the reading/writing account of the origin of SNARC were true, one might expect there to be faster left responses to letters from the beginning of the alphabet and faster right responses to letters from the end of the alphabet. In other words, the effect should be equally present, if not even stronger, in the source domain of the spatial bias. The empirical findings concerning this expectation are contradictory. Dehaene et al. (1993, experiment 4) and Fischer (2003, experiment 2) both asked their participants to classify letters as consonants or vowels and failed to find reliable spatial associations with letter positions in the alphabet. On the other hand, Gevers et al. (2003, experiment 2) reported a spatial bias as a result of the ordinal qualities of letters in the same task (left bias for early and right bias for late ordinal alphabet positions). These conflicting results may be due to the larger statistical power in the latter study; but the strength of the spatial association for letters was surprisingly weak compared to that typically obtained for digits (see Wood et al., 2008, for further discussion of effect sizes of SNARC across different tasks).

A closer look at the experimental evidence offers further mixed support for the reading account of SNARC. Dehaene et al. (1993, experiment 7) measured the SNARC effect in Iranian students who initially learned to read from right to left and then moved to a Western country with left-to-right reading habits. The results showed a reversed horizontal SNARC for some Iranians who had only recently arrived in France, suggesting that they had not yet abandoned their original reading/writing habits, and thus mapped small numbers on to right space and larger numbers on to left space. This study was influential in generating the widely received view that reading habits form the basis or origin for SNARC. However, a closer look at the results shows that this conclusion is not convincing because no measurements of SNARC were taken from participants who were still in Iran, and who should then all show a reversed SNARC. Instead, the proposal of a reading-based origin of SNARC rested on extrapolating a regression line beyond the given data, merely predicting the reversed SNARC for participants still living in a right-to-left writing culture.

Addressing this prediction from Dehaene et al.’s (1993) seminal study, Zebian (2005) measured the time it took monolingual Arab (right-to-left) readers to answer the question ‘Are the two presented digits the same?’ In critical trials, the smaller of two digits appeared either on the left or the right side of the display, and both conditions required ‘no’ responses. Response latencies were recorded with a voice key. Zebian (2005, experiment 1a) discovered an advantage for small numbers on the right side of the display, and this was taken as support for the role of reading direction in the shaping of the reverse SNARC. However, the more typical finding with verbal responses is that no spatial-numerical bias emerges at all (e.g., Keus and Schwarz, 2005; Keus et al., 2005), and this was also the case in a control group of left-to-right reading Western participants in Zebian’s own study. This leaves open whether the adopted method actually tapped into the SNARC effect.

Several other studies are in conflict with the proposed link between SNARC and reading. First, Japanese participants (who read from top to bottom, as well as from left to right) show a SNARC effect that runs opposite to their reading and writing habits (Ito and Hatta, 2004): they associate small digits with lower response keys and larger digits with upper response keys.

Related to this point, it is hard to see how the reading/writing hypothesis could at all account for vertical SNARC effects in Western cultures that do not have vertical reading habits. A vertical SNARC effect in Western participants has been documented with eye-movement responses, showing faster downward saccade initiation in response to small digits and faster upward responses to larger digits (Schwarz and Keus, 2004). For hand movements, the available results pertaining to a vertical SNARC effect are somewhat mixed: Seron and Pesenti (2001) and Sciama et al. (1999, experiment 1) also found an association of small digits with lower keys and larger digits with upper keys, consistent with Schwarz and Keus’s (2004) finding and the report by Ito and Hatta (2004; see also Ishihara et al., this volume). Kim and Zaidel (2000), Stewart et al. (2004) and Hung et al. (2008) reported a response bias for the opposite association, the latter being consistent with the reading direction of their Chinese participants. Interestingly, Hung et al.’s readers were Chinese-English bilinguals, and their spatial mapping of numbers depended on the language they were shown in, with a horizontal mapping for Arabic digits only and a vertical mapping for Chinese symbols only (shown in separate blocks). Our own data (see below, the ‘Modification of SNARC’ section) support the small magnitude–lower key association, and this also makes sense from an embodied cognition point of view: small numerosities of objects lead to shallower piles when compared to larger numerosities, thus instantiating a bottom-to-top association for increasing magnitudes.

Returning now to the critical assessment of the influence of reading habits on SNARC, it has recently become clear that directional reading habits must be distinguished for text processing as opposed to number processing. The distinction was suggested after studying Israeli readers who do not normally show a SNARC effect. Hebrew script is read from right to left but the numbers are still read from left to right. Such opposing spatial activities seem to create directionally incompatible habits for the two types of materials, and it seems that these tend to cancel each other out in the parity task that is typically used to assess SNARC. This conclusion was reached by Shaki et al. (2009), who compared SNARC in Canadians, Palestinians and Israelis. Canadians, who read both numbers and text from left to right, showed the typical Western SNARC where small numbers were associated with left space and larger numbers were associated with right space. Conversely, Palestinian participants, who read both Arabic text and numbers from right to left, showed a reliable reverse SNARC, where small numbers were associated with right space and larger numbers were associated with left space. Most importantly, the Israeli participants showed no reliable SNARC, suggesting that the two conflicting reading habits might have prevented the development of a spatial mapping strategy for numbers.

A set of three recent studies of the relation between SNARC and the reading process itself converge on the conclusion that the influence of reading on SNARC is fleeting at best. In the first study, Shaki and Fischer (2008) asked bilingual Russian-Hebrew readers to perform the parity task both before and after they had read either a short Russian or a short Hebrew paragraph. The typical Western SNARC persisted after reading the left-to-right Cyrillic Russian script, but a significantly reduced SNARC effect was found after reading the right-to-left Hebrew script. Note that the relevant comparisons were taken within the same participants, and the order of reading conditions was counterbalanced, making this a methodologically powerful assessment of the reading claim. This finding shows that reading habits, as laboriously acquired as they may be, are not very persistent at all in their influence on SNARC.

In the second of this recent triplet of studies, Fischer et al. (2009) asked another group of bilingual Russian-Hebrew readers to continuously make parity judgements while alternately showing them Arabic digits and number words. Importantly, the number words were shown randomly in either Cyrillic or Hebrew script, thus unpredictably imposing different reading directions. This study found a rapid change of SNARC as a result of the previously required reading direction: the left-to-right SNARC appeared within the Russian context (both for number words and for the subsequent Arabic digits), but it vanished into insignificance in the Hebrew context, again within the very same participants, and literally from one second to the next. These results show that reading a single word is enough to change the mapping between numbers and space, thus affecting our numerical cognition. In both of these studies, an auditory control condition identified the direction of the recent scanning activity (as opposed to an aspect of language processing) as the factor that influenced the spatial-numerical mapping.

Could it not be argued that these two studies actually underline the role of reading for SNARC? After all, they show how reading exerts a powerful and immediate influence on SNARC. Thus, it may be the case that reading habits are the sole factor influencing SNARC after all. The third study in the set refutes this interpretation because it shows that SNARC changes even during reading. Fischer et al. (2010) asked their participants to read a set of 20 short cooking recipes, one per page. This genre contains many descriptions of quantities and so lends itself to the flexible positioning of digits in the text. The authors manipulated the position of digits in each text so that digits 1 to 4 were on the left side of the page and digits 6 to 9 on the right side for one group, whereas digits 1 to 4 were on the right side of the page and digits 6 to 9 on the left side for another group. This created SNARC-congruent and SNARC-incongruent reading conditions, respectively. The SNARC was measured before and after reading these recipes. Reflecting their random assignment to the two conditions, the two groups had similar typical SNARC effects before reading the recipes. Importantly, after reading these recipes for just 20 minutes (and answering two comprehension questions for each recipe), the SNARC incongruent group no longer mapped numbers on to space, whereas the SNARC effect was unchanged in the congruent group. A second experiment replicated this finding with two groups of Hebrew readers, assuring us that it is indeed possible to change SNARC during reading. This control experiment also succeeded in creating a rare occasion where Israeli readers do exhibit a SNARC effect: the post-test in the ‘incongruent’ (small numbers on the right side) group showed that their brief experience with small numbers in right-side locations was sufficient to remove the previously existing conflict with reading direction, and to reveal a reliable number-to-space mapping in Hebrew readers.

A further lesson from this last study is that positional associations of numbers are powerful determinants of SNARC. This insight suggests that it may be important to determine the systematic probability of a given digit appearing in the first, second, third, etc. position of real-life multi-digit numbers. Interestingly, there seems to be a universal bias in favour of small numbers to be associated with the leftmost position in long digit strings. This fact is known as the Newcomb-Benford law (Newcomb, 1881; Benford, 1938). According to this law, the probability of digit ‘1’ occurring in the first, second, third or fourth position of multi-digit numbers that are drawn randomly from real life (e.g., by measuring weights of crushed stone fragments; Kreiner, 2003), is usually 0.37, 0.19, 0.12, and 0.09, respectively (for review, see Burns, 2009). This lawful pattern in numerical descriptions of real-world facts raises the possibility that our encounters with digit strings may have contributed to the implicit association of small numbers with left space (in a digit string-based reference frame).

To summarize this section, recent studies converge in showing that the influence of reading habits on SNARC is not as persistent and long-lived as previously thought. Nevertheless, reading direction does exert an influence on SNARC, in a situation-dependent fashion and in conjunction with other influences. It is therefore worth looking at how these various spatial biases are acquired. This leads us to the second section of this chapter in which developmental studies of SNARC will be reviewed to show that SNARC emerges well before schooling in (very) early childhood.

Reading skills are typically acquired during the first few years of schooling and then further perfected throughout the rest of one’s life. Given the small contribution to SNARC from reading that was established in the first section of this chapter, one would therefore expect the SNARC effect to increase with age. Although there are apparently (and surprisingly!) no systematic studies of SNARC across different age groups available yet, Wood et al. (2008) conducted a meta-analysis of 17 SNARC experiments, some of which included older participants as controls for neurological patients. A linear regression of effect sizes against participant age (Wood et al., 2008: figure 3) confirms that the effect size of SNARC does increase by a third of a unit with each year of age. A possible explanation for this increased SNARC with age might be the well-known general reduction of inhibitory cognitive control processes in older healthy adults, as measured in priming and interference tasks (e.g., Hasher and Zacks, 1988). Thus, task-irrelevant spatial information associated with numbers may affect performance in older people even more when compared to younger adults.

Looking at the other end of the age continuum, the regression analysis by Wood et al. (2008) implies that a SNARC effect cannot be present under the age of 9.5 years, where their regression line first reliably deviates from a zero effect. Coincidentally, this prediction would be consistent with the results obtained by Berch et al. (1999). These authors showed that the systematic left-to-right spatial mapping of numbers in children performing the parity task first emerged after about three years of schooling, at the age of just over 9 years. Thus, it was argued that acquisition of reading and writing skills might be a prerequisite for the directional bias in numerical cognition. There is, however, a problem with the interpretation of this null effect in the younger groups: speeded parity judgements do require a considerable amount of attention and cooperation from participants, and it may have been the case that children younger than 9 years of age were simply not able to sustain their attention long enough to produce reliable data, thus making it difficult to detect the SNARC signature in the (possibly quite noisy) response times. Using simpler and more child-friendly tasks might be more suitable for detecting SNARC at a younger age. We begin this search by looking at experimental evidence before moving to more naturalistic behaviours that associate numbers with space.

With regard to experimental procedures, van Galen and Reitsma (2008) tested 7-, 8- and 9-year-old Dutch children. They found a significant SNARC even for the youngest Dutch children (aged 7 years) when a magnitude classification task was used instead of the parity judgement task. In this task the children merely had to classify each digit as being larger or smaller than a reference value, and responses were given on lateralized buttons in accordance with each of two counterbalanced rules (‘left button for smaller’ vs. ‘right button for smaller’). This result extends the age range for SNARC downward by two years compared to Berch et al.’s (1999) study, and reinforces the suspicion that the parity task is not suitable for measuring SNARC in young children. Interestingly, van Galen and Reitsma (2008) did not find evidence for an increase in the size of SNARC with increasing age, as would be expected on the basis of the meta-analysis by Wood et al. (2008). Thus, the (presumably) more advanced reading skills of the older children in their study were not associated with a stronger SNARC. A simple detection task, where centrally presented digits were randomly followed by targets in the left or right visual field, did not lead to attention biases in the youngest group, although it did in the older children, just as it does in adults (Fischer et al., 2003). Thus, a seemingly simple task that just requires pressing a single button was also apparently unsuitable for uncovering an existing SNARC. However, two explanations for the lack of SNARC in the detection task are possible: the youngest children may not have paid attention to the numbers, either because they were not predictive of the targets, or because they could not yet control their attention deployment as well as older children. A follow-up study with predictive numbers would resolve this issue.

A further experimental approach that may lend itself to studies of SNARC with young children utilizes the size congruity effect. The rationale is that, in order to associate numbers with space, children must first be able to interpret number symbols as indicators of magnitude. To assess this knowledge, they are asked to perform the magnitude classification task described above, but the digits appear randomly in either a small or a large font. This manipulation creates congruent and incongruent relations between symbol sizes and symbol meanings. A size congruity effect (faster and more accurate decisions in conditions with congruent compared to incongruent relationships between physical and numerical size) would then reflect spontaneous magnitude comprehension (Henik and Tzelgov, 1982). In their recent review of the developmental literature, Göbel et al. (2011) conclude that the size congruity effect already emerges between 5 and 6 years of age, but that the onset age varies across cultures and depends on cultural and linguistic differences in early acquisition and training of mathematics.

Both the magnitude classification task and the size congruity effect rely on the children’s ability to comprehend number meaning, and they infer the spatial association from differences in decision speed for spatial responses. Other tasks directly probe spatial perception and behaviour to assess SNARC in children. In a variant of Piaget’s classical conservation task, Lonnemann et al. (2008) asked 8- to 9-year-old children to indicate which of two numerical distances in visually presented triplets was larger. Numerical and spatial distances were orthogonally manipulated, such that nearby or distant magnitudes were either spatially close or far apart. This task-irrelevant spacing manipulation affected the comparison of numerical distances, showing that children, just like adults, experience an interaction between space and number meaning.

De Hevia and Spelke (2009) recently asked 5-year-old pre-schoolers and 7-year-old pupils to mark the midpoint of lines that were flanked by either Arabic digits or different numerosities of dots (while avoiding confounds of spatial extent). Already the youngest children showed a bias towards the larger numerosity, but number symbols failed to induce biases even at age 7, although they did so in adult controls (see also Fischer, 2001). Thus, in the light of the results reported by van Galen and Reitsma (2008), the apparently simple task of manually bisecting lines may not be suitable for discovering the presence of SNARC. Again, there are several possible explanations for this insensitivity of the bisection task. One unlikely possibility is that the manual aiming requirements of the task are too demanding for the younger children. Another unlikely explanation is a developmental difficulty in associating line lengths with magnitudes. This possibility has been ruled out with a recent habituation study by de Hevia and Spelke (2010). In this study, 18-month old infants were first habituated to increasing numerosity displays. They then dishabituated less when being exposed to increasing line lengths compared to decreasing line lengths. This shows that a propensity to associate numbers with space is already present in very young children, although it may or may not be spatially biased at this stage (see also Wagner et al., 1981). The most likely explanation is that the magnitude meaning of the flanker symbols was task-irrelevant (as in the detection task of van Galen and Reitsma, 2008).

Let’s now move away from artificially designed laboratory tasks and look instead at naturally occurring spatial-numerical behaviour to further determine the developmental origin of SNARC. One of the earliest numerical activities in children is counting, and it occurs either on physical objects or on one’s fingers. With regard to object-based counting, Opfer and Thompson (2006) reported that already at the very young age of 3–5 years 98 per cent of American children prefer to count a row of objects from left to right (see also Opfer and Furlong, 2011). Thus, a left-to-right bias is clearly present before reading training ensues. The question emerges where this bias comes from, and one obvious candidate is finger counting. Finger counting is a universal mechanism for the acquisition of number concepts (Fuson, 1988; Butterworth, 1999) and seems to date back at least 25,000 years (Göbel et al., 2011). The Romans, whose hand shapes during finger counting provided the inspiration for their number symbols, counted up to 99 on the left hand (Bechtel, 1909) and this was still the prescribed starting hand in medieval counting guides. Dantzig (1930/1954) argued that ‘primitive man rarely goes about unarmed. If he wants to count he tucks his weapon under his arm, the left arm as a rule, and counts on his left hand, using his right hand as a check-off’ (1954: 13).

In Western adults living today there is usually a preference to begin counting on the fingers of the left hand, regardless of their handedness (Fischer, 2008; Lindemann et al., 2011). This bias was presumably present since their childhood, but surprisingly, there are very few studies that have looked at the spatial preferences of finger counting in children. In a classical report, Conant (1896/1960: 437ff.) stated that almost all of 206 children (aged 4–8 years) in a US public school began to count with their left hand. But Sato and Lalain (2008) recently reported that from 4 years onwards there seems to be a strong tendency to use first the right hand to count from 1 to 5, and then to move to the left hand to count from 6 to 10. This observation is in conflict with several reports of a preference to start counting on the left hand in most adults, but it becomes clear that different countries in the Western world may have different counting preferences, due to as of yet unexplained cultural factors (Lindemann et al., 2011; see also Göbel et al., 2011).

From this brief review of some developmental studies it seems clear that there is a predisposition in children to associate magnitudes with space. This predisposition supports, and is later expressed in, the use of one’s fingers to enumerate objects. Nevertheless, it remains to be explained why there is a preference to start finger counting on the left hand (at least in several Western countries), so that small numbers become associated with fingers of the left hand and, by extension, with left space. One answer to this question is to refer to children’s powerful ability to learn from observing their caregivers. While there is a vast literature on observation learning and imitation, this literature does not seem to have addressed the systematic patterns of finger counting and their origin. Therefore, the next section describes a set of training studies that explored this important issue. The results of these studies lead to the suggestion that passive observational learning might be sufficient to shape one’s association of numbers with space.

MODIFICATION OF SNARC

Much can be learned about the origin of SNARC from looking at how it can be modified. Yet there are hardly any studies that have tracked the time course of spatial-numerical experiences in a systematic fashion. The reading studies by Shaki, Fischer and colleagues (described above in the ‘Reading habits and SNARC’ section) are an exception to this trend because they manipulated a spatial or spatial-numerical experience and assessed the consequences of this manipulation for SNARC. Further insights can be gained from measuring SNARC at several points during such experiences, and this section describes a few such studies.

Think back to the study that showed how SNARC changed while participants were reading 20 SNARC-incongruent cooking recipes (Fischer et al., 2010; see ‘Reading habits and SNARC’ section). How many cooking recipes have to be read before an effect of the incongruent number placement emerges? To answer this question, 21 new participants performed the parity test first as a pretest, and then again after reading the first, and another five, and another 14 SNARC-incongruent recipes only (methods were otherwise identical to Fischer et al., 2010). SNARC was reliable before reading, after one, and after five recipes, and only began to be diluted after reading all 20 recipes. Thus, a consecutive reading of more than 15 incongruent recipes appears to be needed before the default SNARC mapping is affected. Moreover, the intermittent experience of non-lateralized digits (in the parity tasks) may have diluted the spatial re-mapping effect induced by reading the incongruent recipes.

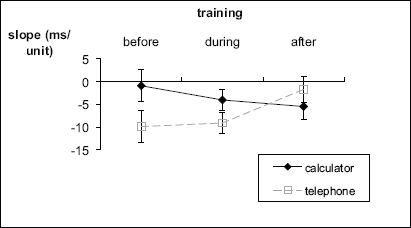

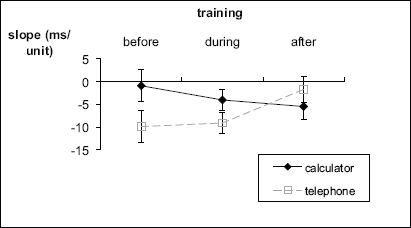

In a pioneering study Pieter Coeman used a data entry task to systematically modify SNARC over time (Coeman and Fischer, 2004, experiment 1). His task involved tapping numbers 1–9 that were visually presented on a screen into a 3x3 grid on a table. Importantly, half the participants were told the grid, which showed no numbers, reflected a calculator keypad (where digits 1, 2 and 3 constitute the bottom row, consistent with the population stereotype for vertical SNARC), whereas the other half were told the same grid reflected a telephone keypad (where digits 1, 2 and 3 constitute the top row). The vertical SNARC was assessed before, during and after data entry in a vertical parity task (by positioning keys 2 and 8 of the numerical keyboard centrally under the screen). Regression analyses confirmed a reliable overall vertical SNARC before training that changed systematically depending on the type of training (see Figure 12.1). Specifically, the vertical SNARC effect in the telephone group disappeared while it remained in the calculator group. Direct comparisons of SNARC slopes before and after training showed a significant change in the telephone group after only 24 minutes of data entry.

Figure 12.1 SNARC results from Coeman’s first experiment. Most participants showed the calculator-type association (small numbers are low, larger numbers high) before training. This association was strengthened by further calculator-based data entry (black diamonds) and abolished by only 24 minutes of data entry on a telephone-type layout (white squares).

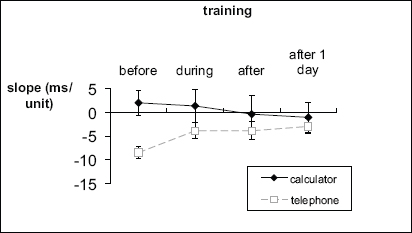

How much training would be required to reverse the SNARC completely in the telephone group? How long does the training effect last? And, most importantly, what cognitive aspect of the experience with numbers in space induces a SNARC effect? Two promising candidates for establishing such links could be active behaviour and passive observational learning. Previous research suggests that active movements are crucial in establishing spatial mappings (e.g., Held, 1965). With regard to numbers, Rossetti et al. (2004) showed that brief periods of pointing with prismatic goggles changed the response bias in a number interval bisection task in neurological patients. This research predicted that passively looking at another person typing numbers should not suffice to modulate one’s SNARC. Testing this prediction, Coeman studied pairs of participants who adopted different roles during data entry: the active participants again saw numbers on a screen and tapped them out on the empty grid in front of them, just as in experiment 1, according to one of two pre-instructed number-to-space mappings. The passive participants could not see the digits to be entered by the active participants but were individually instructed to interpret the grid as reflecting one of the two possible number-to-space mappings (telephone or calculator). They were also asked to verbally report the occurrences of certain target digits, so that we can be sure that they paid proper attention. The experiment typically lasted for 100 minutes. The next day, the participants returned and completed the parity task one final time. Coeman replicated his initial finding of rapid changes in SNARC, as shown in Figure 12.2. It is worth briefly noting here that the small numbers-top mapping (i.e. the telephone), which is less natural from an embodied cognition point of view, also appeared to be the less robust and more easily changeable mapping, but this prediction needs to be tested more thoroughly in future. More importantly here, Coeman also found very similar changes for active and passive participants (not shown in the figure). In other words, the SNARC changed even without actively responding to numbers in space. This finding is consistent with the results of the cooking recipe studies and supports the idea of observational learning as a sufficiently strong mechanism to establish SNARC, possibly even in very young infants. After all, infants and young children are exposed to the spatially directional behaviours of their caregivers, from counting off objects to reading bedtime stories (possibly even using an index finger to point to objects and words). These preliminary findings suggest that the visually observed component, not the motor component, of our visuomotor interactions contributes to the pervasive association between magnitudes and space that is captured in the SNARC.

Figure 12.2 SNARC results from Coeman’ s second experiment. Participants were grouped by their pre-experimental vertical SNARC and then trained with the conflicting mapping. Their SNARC was rapidly reduced and this training effect persisted for at least one day. Data are averaged across active and passive participants as they showed similar results.

CONCLUSIONS

The pervasive association between number magnitudes and space emerges during early development and might reflect our propensity to learn from visually observed experiences. Observational and other forms of associative learning have been proposed to lie at the heart of embodied cognition, according to which sensory and motor experiences become part of our conceptual knowledge (Pulvermüller, 2005). This view is supported by the empirical findings reviewed in this chapter, which will now be summarized. First, it is time to modify the long-held belief that reading habits are longstanding and robust. While it does take considerable time to acquire directional reading skills, they do not subsequently exert a persistent influence on the direction of SNARC. Instead, the immediate reading-related spatial scanning influences SNARC rapidly and flexibly, and even temporarily experienced positional associations of numbers in space can override these long-standing habits, consistent with an associative learning account that places heavier weight on more recent experiences. Independent of this, it is possible that the directional interaction with letter symbols constitutes an experience that supports and facilitates a similar spatially directional interaction with digits symbols. Second, well before we begin to learn to decode letter symbols and to read words, we are already biased in our spatial mapping of magnitudes. This bias could be the result of culture-specific observational learning, as suggested on the basis of some initial training studies with adults.

Understanding SNARC as an instance of embodied cognition brings the entire domain of numerical cognition, long thought to be a domain par excellence of abstract thought, into the focus of embodiment research. Spatial-numerical interactions seem well suited for such research because the same small set of digit symbols can be used to activate clearly defined knowledge representations in a wide range of people. A powerful repertoire of methods is already in place to determine the attributes of SNARC across a wide range of behavioural domains, thus furthering our understanding of human cognition more generally.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was sponsored by an EPSRC grant (EP/F028598/1) on ‘Vision, Action and Language Unified by Embodiment’ and by the AHRC ‘Beyond Text’ initiative.

REFERENCES

Andres, M., Olivier, E. and Badets, A. (2008). Actions, words, and numbers. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(5): 313–317.

Barsalou, L.W. (2008). Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59: 617–645.

Bechtel, E.A. (1990). Finger counting among the Romans in the fourth century. Classical Philology, 4(1): 25–31.

Benford, F. (1938). The law of anomalous numbers. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 78(4): 551–572.

Berch, D.B., Foley, E.J., Hill, R.J. and Ryan, P.M. (1999). Extracting parity and magnitude from Arabic numerals: developmental changes in number processing and mental representation. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 74: 286–308.

Burns, B. (2009). Sensitivity to statistical regularities: people (largely) follow Benford’s law. Proceedings of the Cognitive Science Society: paper 637.

Butterworth, B. (1999). The Mathematical Brain. London: Macmillan.

Coeman, P.D.N. and Fischer, M.H. (2004). Rotating the mental number line: rapid effects of training. Unpublished manuscript.

Dantzig, T. (1930/1954). Number: The Language of Science, fourth edn. New York: Doubleday.

Dehaene, S., Bossini, S. and Giraux, P. (1993). The mental representation of parity and number magnitude. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 122 (3): 371–396.

de Hevia, M.D. and Spelke, E.S. (2009). Spontaneous mapping of number and space in adults and young children. Cognition, 110(2): 198–207.

de Hevia, M.D. and Spelke, E.S. (2010). Number-space mapping in human infants. Psychological Science, 21: 653–660.

de Hevia, M.D., Vallar, G. and Girelli, L. (2008). Visualizing numbers in the mind’s eye: the role of visuo-spatial processes in numerical abilities. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 32: 1361–1372.

Fias, W. and Fischer, M.H. (2005). Spatial representation of number, in Campbell, J.I.D. (ed.), Handbook of Mathematical Cognition (pp. 43–54). New York: Psychology Press.

Fischer, M.H. (2001). Number processing induces spatial performance biases. Neurology, 57: 822–826.

Fischer, M.H. (2003). Spatial representations in number processing: evidence from a pointing task. Visual Cognition, 10(4): 493–508.

Fischer, M.H. (2008). Finger counting habits modulate spatial-numerical associations. Cortex, 44: 386–392.

Fischer, M.H. and Zwaan, R.A. (2008). Embodied language: a review of the role of the motor system in language comprehension. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 61(6): 825 – 850.

Fischer, M.H., Castel, A.D., Dodd, M.D. and Pratt, J. (2003). Perceiving numbers causes spatial shifts of attention. Nature Neuroscience, 6(6): 555–556.

Fischer, M.H., Shaki, S. and Cruise, A. (2009). It takes just one word to quash a SNARC. Experimental Psychology, 56(5): 361–366.

Fischer, M.H., Mills, R. and Shaki, S. (2010). How to cook a SNARC: number placement in text rapidly changes spatial-numerical associations. Brain and Cognition (in press).

Fuson, K.C. (1988). Children’s Counting and Concepts of Number. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Gevers, W., Reynvoet, B. and Fias, W. (2003). The mental representation of ordinal sequences is spatially organized. Cognition, 87: B87–B95.

Göbel, S.M., Shaki, S. and Fischer, M.H. (2011). The cultural number line: a review of cultural, educational and linguistic influences on number processing. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology (in press).

Groen, G.J. and Parkman, J.M. (1972). A chronometric analysis of simple addition. Psychological Review, 79: 329–343.

Hasher, L. and Zacks, R.T. (1988). Working memory, comprehension, and aging: a review and a new view, in Bower, G.H. (ed.), The Psychology of Learning and Motivation (Vol. 22, pp. 193–225). New York: Academic Press.

Held, R. (1965). Plasticity in sensory-motor systems. Scientific American, 213(5): 84–94.

Henik, A. and Tzelgov, J. (1982). Is three greater than five: the relation between physical and semantic size in comparison tasks. Memory and Cognition, 10: 389–395.

Hubbard, E.M., Piazza, M., Pinel, P. and Dehaene, S. (2005). Interactions between number and space in parietal cortex. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 6(6): 435–448.

Hung, Y.H., Hung, D.L., Tzeng, O.J.L. and Wu, D.H. (2008). Flexible spatial mapping of different notations of numbers in Chinese readers. Cognition, 106(3): 1441–1450.

Ito, Y. and Hatta, T. (2004). Spatial structure of quantitative representation of numbers: evidence from the SNARC effect. Memory and Cognition, 32(4): 662–673.

Keus, I.M. and Schwarz, W. (2005). Searching for the locus of the SNARC effect: evidence for a response-related origin. Memory and Cognition, 33: 681–695.

Keus, I.M., Jenks, K.M. and Schwarz, W. (2005). Psychophysiological evidence that the SNARC effect has its functional locus in a response selection stage. Cognitive Brain Research, 24: 48–56.

Kim, A. and Zaidel, E. (2000). Vertical representation of the number line in two cerebral hemispheres. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 12 (Suppl.): 16.

Knops, A., Thirion, B., Hubbard, E.M., Michel, V. and Dehaene, S. (2009). Recruitment of an area involved in eye movements during mental arithmetic. Science, 324: 1583–1585.

Kreiner, W.A. (2003). On the Newcomb-Benford Law. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung, Section A-A, Journal of Physical Sciences, 58(11): 618–622.

Lindemann, O., Alipour, A. and Fischer, M. (2011). Finger counting habits in Middle-Eastern and Western individuals: an online survey. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology (in press).

Loetscher, T., Bokisch, C.J., Nicholls, M.E.R. and Brugger, P. (2010). Eye position predicts what number you have in mind. Current Biology, 20(6): R264–R265.

Lonnemann, J., Krinzinger, H., Knops, A. and Willmes, K. (2008). Spatial representations of numbers in children and their connection with calculation abilities. Cortex, 44 (4): 420–428.

Newcomb, S. (1881). Astronomical observatories. Science, 2(60): 377–380.

Opfer, J.E. and Furlong, E.E. (2011). How numbers bias preschoolers’ spatial search. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology (in press).

Opfer, J.E. and Thompson, C.A. (2006). Even early representations of numerical magnitude are spatially organized: evidence for a directional magnitude bias in pre-reading preschoolers, in Sun, R. and Miyaki, N. (eds), Proceedings of the XXVIII Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Pinhas, M. and Fischer, M.H. (2008). Mental movements without magnitude? A study of spatial biases in symbolic arithmetic. Cognition, 109: 408–415.

Pulvermüller, F. (2005). Brain mechanisms linking language and action. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 6: 576–582.

Rossetti, Y., Jacquin-Courtois, S., Rode, G., Ota, H., Michel, C. and Boisson, D. (2004). Does action make the link between number and space representation? Psychological Science, 15(6): 426–430.

Sato, M. and Lalain, M. (2008). On the relationship between handedness and hand-digit mapping in finger counting. Cortex, 44(4): 393–399.

Schwarz, W. and Keus, I.M. (2004). Moving the eyes along the mental number line: comparing SNARC effects with saccadic and manual responses. Perception and Psychophysics, 66(4): 651–664.

Sciama, S.C., Semenza, C. and Butterworth, B. (1999). Repetition priming in simple addition depends on surface form and typicality. Memory and Cognition, 27(1): 116–127.

Seron, X. and Pesenti, M. (2001). The number sense theory needs more empirical evidence. Mind and Language, 16(1): 76–88.

Shaki, S. and Fischer, M.H. (2008). Reading space into numbers: a cross-linguistic comparison of the SNARC effect. Cognition, 108(2): 590–599.

Shaki, S., Fischer, M.H. and Petrusic, W.M. (2009). Reading habits for both words and numbers contribute to the SNARC effect. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 16(2): 328–331.

Stewart, L., Walsh, V. and Frith, U. (2004). Reading music modifies spatial mapping in pianists. Perception and Psychophysics, 66(2): 183–195.

van Galen, M.S. and Reitsma, P. (2008). Developing access to number magnitude: a study of the SNARC effect in 7- to 9-year-olds. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 101(2): 99–113.

Wagner, S., Winner, E., Cicchetti, D. and Gardner, H. (1981). ‘Metaphorical’ mapping in human infants. Child Development, 52: 728–731.

Wood, G., Nuerk, H.-C., Willmes, K. and Fischer, M.H. (2008). On the link between space and number: a meta-analysis of the SNARC effect. Psychology Science, 50(4): 489–525.

Zebian, S. (2005). Linkages between number concepts, spatial thinking, and directionality of writing: the SNARC effect and the REVERSE SNARC effect in English and Arabic monoliterates, biliterates, and illiterate Arabic speakers. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 5(1–2): 165–190.