Embodied semantics for language related to actions: A review of fMRI and neuropsychological research

INTRODUCTION

Embodied semantics states that concepts are represented within the same sensory-motor circuitry that processes experiences of that concept (Barsalou, 1999; Damasio, 1989; Damasio and Tranel, 1993; Feldman and Narayanan, 2004; Glenberg and Kaschak, 2002a; Pulvermüller, 2005; Pulvermüller et al., 2005). For example, the concept of “throwing” would be represented in sensory-motor areas that represent throwing actions; the concept of “red” would be represented by sensory areas that are involved in color processing; and so forth. It has also been posited that metaphors may also be represented in the same manner. For example, the metaphor “bite off more than you can chew” would involve the motor representations related to biting and chewing (Lakoff and Johnson, 1999). As metaphorical speech is speculated to dominate a large portion of human thought (Lakoff and Johnson, 1999), embodied semantics, thus, would be a framework for much of human language and thought.

While this theory extends for all concepts, most research has been conducted on concepts related to actions. This is due, in part, to the discovery of the mirror neuron system, which, with its multimodal representations (Rizzolatti and Craighero, 2004), has been speculated to be important for conceptual representation of actions (Gallese and Lakoff, 2005; see also Borghi, this volume; Coello and Bidet-Ildei, this volume; Corballis, this volume; Gentilucci and Campione, this volume; Jacob, this volume). This chapter is not meant to be a comprehensive review of the literature on this topic; instead it aims to delineate trends in this line of research and suggest future directions. Here we focus on embodied semantics for actions (kicking, grasping, biting, etc.), review neuropsychological and brain-imaging studies, and specifically consider the theory for somatotopic activation for language in the premotor cortex. We conclude by considering a few studies on embodied semantics outside the motor regions.

NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

We first consider lesion data for assessing the degree to which motor regions are essential for action verb processing. Indeed, lesion data is the strongest test of the embodied semantic theory—that is, if motor regions are necessary for conceptual representation (and not just peripheral to it), then a lesion in the specific motor region should result in a deficit in conceptual representation of the corresponding action. Several neuropsychological studies have explored this question, and all point to a common result that motor regions are in fact involved in action comprehension. However, whether anterior or posterior regions are involved remains inconclusive. One study that supports posterior involvement is by Heilman et al. (1982), where individuals with left hemisphere lesions with apraxia were tested on action comprehension (see also Stieglitz Ham and Bartolo, this volume). While there were no detailed reports of the neuropathology, the patients were divided into two groups (posterior and anterior lesions). The latter would likely include parietal regions while the former the premotor cortex. Results indicated that only patients with posterior lesions showed a deficit in action comprehension tests, even though both groups had similar degrees of motor impairments (Heilman et al., 1982; Rothi et al., 1985). This result is reminiscent of Leipmann’s traditional model of praxis (Leiguarda and Marsden, 2000), which proposes that the left parietal regions have representations that can be utilized for both action production and comprehension (De Renzi et al., 1986; Kertesz and Ferro, 1984).

By contrast, other studies indicate that lesions to the frontal premotor areas result in an action comprehension deficit. One interesting case is the investigation of action comprehension in individuals with motor neuron disease (MND), a neurodegenerative disease selectively affecting the motor system (Bak and Hodges, 1999, 2004; Bak et al., 2001). Individuals with MND were found to have a selective deficit in action verb production and comprehension as compared to the processing of nouns. Damage to the motor and premotor cortex, including the inferior frontal gyrus (BA 44/45), was found in postmortem examination of affected MND patients. Thus, these frontal motor regions seem to be essential not only for motor processing, but also for processing action verbs (Bak et al., 2001). Examinations of patients with frontotemporal dementia (Cappa et al., 1998) and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) (Daniele et al., 1994) also support the notion that a deficit in verb processing may be associated with damage to frontal and frontostriatal brain areas.

Finally, a few other studies indicate that both anterior and posterior lesions affect action comprehension. In one study with a large number of participants (90 patients with various lesions in the left or right hemisphere), Tranel et al. (2003) investigated conceptual representation for actions. Subjects were asked to evaluate action attributes from viewing pictures of actions and to compare and match pictured actions. Using a lesion overlap approach and correlating this with scores on tests of action comprehension, they found that the highest incidence of impairment was correlated with lesions to the left premotor/prefrontal cortex, the left parietal region, and the white matter underneath the left posterior middle temporal region (Tranel et al., 2003). Another study that reported comprehension deficits in patients with either anterior or posterior lesions investigated comprehension of visually or verbally presented actions in aphasic patients. While both patients with lesions of premotor or parietal areas were impaired on these tasks, lesions in premotor areas were more predictive of deficits (Saygin et al., 2004). A more recent study investigated language related to the foot, hand, mouth, or no body part in patients with left hemisphere lesions. This study found that motor-related regions were indeed involved in language related to the body; however, there was no evidence for somatotopy and lesions in other brain regions were also correlated with a deficit in processing language associated with actions (Arévalo et al., in press).

Finally, in a large study of 226 patients who were given a battery of six tasks probing lexical and conceptual knowledge of actions, Kemmerer and his colleagues found significant effects in both motor and non-motor regions. Specifically, all six tasks were correlated to the following left hemisphere regions: the inferior frontal gyrus, the ventral precentral gyrus, and the anterior insula. Interestingly, they found that, of the four patients who failed all six tasks, three had lesions in the left inferior frontal gyrus and one in the left posterior middle temporal gyrus. These findings support the theory that the inferior frontal gyrus and perhaps also the posterior middle temporal gyrus are essential to lexical and conceptual representations of actions (Kemmerer et al., in press).

Taken together, results from lesion data indicate that both anterior and posterior components of action processing networks may be essentially involved in action verb processing. It may be that different components of action verb processing involve different components of the network. In addition, it should be noted that none of the neuropsychological studies supports a somatotopic representation for embodied semantics. The exception to this trend is a finding that a lesion to the precentral gyrus where the hand is commonly represented is correlated to deficits in conceptual representation of hand actions (Kemmerer et al., in press). However, this finding would benefit from a similar finding for the foot or mouth. To date, none of the lesion studies found that, for example, action comprehension for hand actions is correlated with dorsal premotor lesions as compared to ventral premotor lesions for the mouth. We come back to this latter result later in this chapter.

EMBODIED ACTION SEMANTICS IN THE PREMOTOR CORTEX

Unlike the lesion data, most fMRI studies on embodied action semantics have focused on the premotor cortex and most have found support for the theory. In one of the first imaging studies on this topic, Hauk et al. found that reading words associated with foot, hand, or mouth actions (e.g., kick, pick, lick) activated motor areas adjacent to or overlapping with areas activated by making actions with the foot, hand, or mouth (Hauk et al., 2004). In another study, Tettamanti et al. (2005) also reported somatotopic activation for reading action-related sentences (dorsal to ventral premotor activations: leg sentences, hand sentences, mouth sentences). Additional support for premotor involvement was found in a study by Aziz-Zadeh and colleagues (2006). They localized foot, hand, and mouth premotor regions of interest in each subject by having them watch foot, hand, and mouth actions. Subjects also read phrases associated with the foot, hand, or mouth. They found that, in each subject, the left hemisphere regions most activated for watching a foot action were also most active for language related to foot actions. A similar significant finding was found for the hand and the mouth (Aziz-Zadeh et al., 2006). However, in this study, somatotopic activation was found only for the hand and mouth (i.e., mouth dorsal to the hand), but not for the foot. Several other groups have also found support for embodied semantics for actions using fMRI (see, for example, Kemmerer et al., 2008; van Dam et al., 2010; Willems et al., 2009), transcranial magnetic stimulation studies (TMS; see, for example, Buccino et al., 2005; Glenberg et al., 2008; Pulvermüller et al., 2005), and electroencephalography (EEG; see, for example, Hauk and Pulvermüller, 2004). Interestingly, one study found that right- and left-handers activated opposite hemispheres when processing action verb meanings, indicating that conceptual representation for actions relies on the same laterality as the motor representations for that action (Willems et al., 2010).

Behavioral methods have also supported embodied conceptual representations for actions. In one study, when measuring reaction times, Glenberg and Kaschak (2002b) found that participants were faster responding to sentences if the response was compatible with the direction of the action implied in the sentence (e.g., “open the drawer” and moving the hand toward the body; Glenberg and Kaschak, 2002b; see also Taylor and Zwaan, this volume). A similar result was found at the word level, where words describing objects usually brought toward the body (cup) were responded to faster when making a compatible movement toward the body than when responding to words that elicit actions away from the body (Rueschemeyer et al., 2010; see also Rueschemeyer and Bekkering, this volume). Effector-specific effects have also been demonstrated, where subjects are faster responding to word pairs when they depict mouth action and the subject responds with the mouth or when they depict hand actions and the subject responds with the hand (Scorolli and Borghi, 2007).

As mentioned previously, in several of the brain-imaging studies, there is some evidence for somatotopic activation, though the regions active are diverse between the studies and the mapping of the foot in relation to the hand and mouth varies across studies. We turn next to the issue of somatotopic activation for action semantics.

SOMATOTOPIC ACTIVATION?

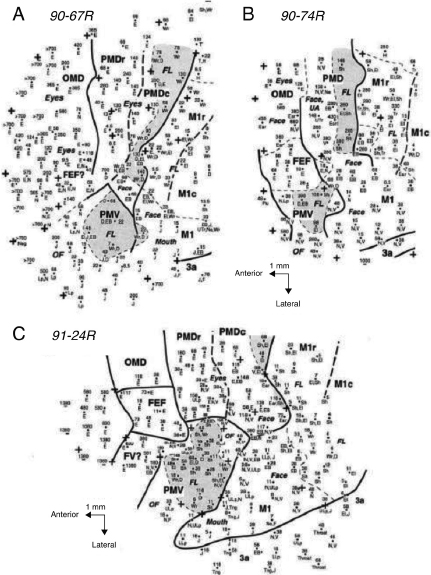

While several studies have claimed some degree of premotor somatotopic activation for action semantics, this is a topic that deserves some further consideration. Perhaps the first place to start is to consider somatotopy for action execution in the premotor cortex. It is noteworthy that two studies of premotor activations for action execution have failed to distinguish between peaks activated for the hand and the foot (Fink et al., 1997; Kollias et al., 2001). Taking a look at data from monkey studies, it is evident how complicated the premotor regions are (Figure 14.1). A simple somatotopy does not describe the organization. Furthermore, it has been noted that the representation of the muscles is not fixed, as previously thought, but fluid and continuously malleable depending on feedback (Graziano, 2006).

In fact, the more one reviews the basic motor literature on the premotor cortex, the more it is apparent that the organization of the human pre-motor cortex is extremely complex and needs further understanding. Unlike the primary motor cortex, which is organized somatotopically, the premotor cortex may be influenced by a number of general organizing principles. For example, Rizzolatti and colleagues have suggested that action planning (e.g. manipulating, reaching) is more important than the actual effector involved (Rizzolatti et al., 1987). Others have posited that distal versus proximal body parts are represented differentially in the premotor cortex (Schubotz and von Cramon, 2003). The current lack of understanding of premotor organization should thus be taken into account in discussing how specific conceptual representations are tied to specific premotor areas.

Nevertheless, some functional imaging studies on action observation, action sounds, and language related to actions have reported somatotopic activation. While a substantial amount of variability in peak coordinates has been reported for somatotopic responses to action observation and linguistic stimuli (Aziz-Zadeh and Damasio, 2008), in general, these studies find that the mouth representations are ventral to the hand representations. The foot representation is much more disputed (Aziz-Zadeh and Damasio, 2008). Indeed, this limited somatotopy may be a reflection of organization by effector, the goal of the action, medial versus proximal distinctions, and so forth, and need not reflect effector-based somatotopy (Schubotz et al., 2003). Furthermore, a lesion study by Arévalo et al. (in press) indicated that, while semantics related to hand, mouth, and foot actions involved motor representations, somatotopy was not found. Thus, it is extremely pertinent to take into account current understandings of the premotor cortex organization before one makes claims on how language representation reflects these patterns.

Figure 14.1 Variation and complexity of the premotor cortex. Microstimulation and architectonic maps for three owl monkeys (Preuss et al., 1996). Of particular interest are the ventral premotor regions (PMV) and rostral and caudal dorsal premotor regions (PMDr, PMDc). Looking at these maps at gross levels, first note the degree of individual differences in distinctions between areas. This should be taken into account when performing analyses using brain-imaging techniques. Second, note the complexity of how the body is represented, implying a much richer and more complicated representation in premotor regions than simply somatotopic organization. Additional information may be found in Preuss et al. (1996).

METAPHORICAL LANGUAGE

Another question that can be asked is how metaphorical phrases related to actions associated with the hand, foot, or mouth engage motor representations. One study that focused on metaphors related to actions (e.g., “bite the bullet,” “grasp the meaning,” “kick the bucket”; see also Rueschemeyer and Bekkering, this volume) looked for overlap between activations elicited by reading those phrases and activations elicited by action observation of the corresponding effectors (e.g., mouth, hand, foot; Aziz-Zadeh et al., 2006). This study did not find evidence for congruent somatotopic activation for action-related metaphors nor significant motor activation in general. However, it is possible that, as all the metaphors in this study were over-practiced metaphors, they no longer evoke motor representations. That is, perhaps during initial learning of a metaphor such as “grasp the idea,” representations related to grasping actions may have been used to understand the metaphor’s meaning. However, once it is learned and commonly used, it may no longer rely on these representations and be linked to, instead, other representations associated with the concept of “understanding.”

Another possibility for finding motor activations for metaphorical language may be to consider that metaphorical processing may take longer than processing concrete sentences. The previously discussed study by Aziz-Zadeh et al. (2006) considered BOLD response for the duration of reading the metaphorical sentences. However, it may be that metaphorical processing takes longer and looking at later times in the BOLD response may be advantageous. One study that performed precisely this later time range analysis did in fact find motor activity idioms corresponding to the hand (“John grasped the idea”) and the foot (“Mary kicked the habit”). Furthermore, they found that activity for foot idioms were dorsal to hand idioms in the motor strip (Boulenger et al., 2009). Further studies in this area are necessary and future research will be important to better understand this possibility and the relationship between action-related metaphors and the motor system.

EMBODIED SEMANTICS FOR THE FACE

Until this point, we have focused on representation of language related to actions made by the foot, hand, and mouth. However, one could ask: How do motor-related regions respond when describing a specific body part rather than an action related to that region?

There have been a few studies on language describing the face. In the first study, participants listened to sentences describing famous and generic faces of individuals as compared to control sentences (i.e., “George Bush has wrinkles around his eyes.”). Data indicated that language describing famous faces specifically modulated activity in the fusiform face area (FFA), a visual face processing area (Aziz-Zadeh et al., 2008). An electrophysiology study also found that language pertaining to faces affected early perceptual encoding (Landau et al., 2010). That study took advantage of a robust and reliable evoked neural response that peaks about 170 ms after the onset of seeing an image of a face (N170). Landau et al. (2010) asked what would happen if an image of a face were preceded by a sentence describing a face as opposed to a sentence describing a scene. They found that the N170 response was larger when face stimuli were preceded by sentences describing faces as compared to sentences describing scenes. While these data do not also test activations in somato-sensory or motor regions, they do support the notion that language can modulate activity even in early visual processing areas.

CONCLUSIONS

With the advance of new brain-imaging techniques, the theory of embodied semantics has now been tested in many studies using multiple approaches. Taken together, brain imaging and behavioral studies support the notion that motor-related regions are involved in conceptual representation of actions. Furthermore, neuropsychological data indicate that involvement of the motor areas is necessary to conceptual representation; however, the location of the involvement (anterior vs. posterior) and how these areas may be part of a larger network for conceptual representation is still disputed. In addition, data from neuropsychological studies and our knowledge of the premotor cortex indicate that somatotopy may not be the best means to investigate this topic, as representations may be more complex than simple somatotopy in the premotor cortex and conceptual representation may be spread to multiple areas. Understanding the network for conceptual representation of actions, how they relate to metaphorical processing, and how this differs from concepts related to body parts in general will be important future steps in this area.

Arévalo, A.L., Baldo, J.V., and Dronkers, N.F. (in press). What do brain lesions tell us about theories of embodied semantics and the human mirror neuron system? Cortex.

Aziz-Zadeh, L. and Damasio, A. (2008). Embodied semantics for actions: findings from functional brain imaging. Journal de Physiologie, 102(1–3): 35–39.

Aziz-Zadeh, L., Wilson, S.M., Rizzolatti, G., and Iacoboni, M. (2006). Congruent embodied representations for visually presented actions and linguistic phrases describing actions. Current Biology, 16(18): 1818–1823.

Aziz-Zadeh, L., Fiebach, C.J., Naranayan, S., Feldman, J., Dodge, E., and Ivry, R.B. (2008). Modulation of the FFA and PPA by language related to faces and places. Social Neuroscience, 3(3–4): 229–238.

Bak, T.H. and Hodges, J.R. (1999). Cognition, language and behaviour in motor neurone disease: evidence of frontotemporal dysfunction. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 10(Suppl. 1): 29–32.

Bak, T.H. and Hodges, J.R. (2004). The effects of motor neurone disease on language: further evidence. Brain and Language, 89(2): 354–361.

Bak, T.H., O’Donovan, D.G., Xuereb, J.H., Boniface, S., and Hodges, J.R. (2001). Selective impairment of verb processing associated with pathological changes in Brodmann areas 44 and 45 in the motor neurone disease-dementia-aphasia syndrome. Brain, 124(Pt 1): 103–120.

Barsalou, L.W. (1999). Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22(4): 577–609; discussion 610–560.

Boulenger, V., Hauk, O., and Pulvermüller, F. (2009). Grasping ideas with the motor system: semantic somatotopy in idiom comprehension. Cerebral Cortex, 19(8): 1905–1914.

Buccino, G., Riggio, L., Melli, G., Binkofski, F., Gallese, V., and Rizzolatti, G. (2005). Listening to action-related sentences modulates the activity of the motor system: a combined TMS and behavioral study. Cognitive Brain Research, 24(3): 355–363.

Cappa, S.F., Binetti, G., Pezzini, A., Padovani, A., Rozzini, L., and Trabucchi, M. (1998). Object and action naming in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Neurology, 50(2): 351–355.

Damasio, A.R. (1989). Time-locked multiregional retroactivation: a systems-level proposal for the neural substrates of recall and recognition. Cognition, 33(1–2): 25–62.

Damasio, A.R. and Tranel, D. (1993). Nouns and verbs are retrieved with differently distributed neural systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 90(11): 4957–4960.

Daniele, A., Giustolisi, L., Silveri, M.C., Colosimo, C., and Gainotti, G. (1994). Evidence for a possible neuroanatomical basis for lexical processing of nouns and verbs. Neuropsychologia, 32(11): 1325–1341.

De Renzi, E., Faglioni, P., Scarpa, M., and Crisi, G. (1986). Limb apraxia in patients with damage confined to the left basal ganglia and thalamus. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 49(9): 1030–1038.

Feldman, J. and Narayanan, S. (2004). Embodied meaning in a neural theory of language. Brain and Language, 89(2): 385–392.

Fink, G.R., Frackowiak, R.S., Pietrzyk, U., and Passingham, R.E. (1997). Multiple nonprimary motor areas in the human cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology, 77(4): 2164–2174.

Gallese, V. and Lakoff, G. (2005). The brain’s concepts: the role of the sensory-motor system in reason and language. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 22: 455–479.

Glenberg, A.M. and Kaschak, M.P. (2002a). Grounding language in action. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 9(3): 558–565.

Glenberg, A.M. and Kaschak, M.P. (2002b). Grounding language in action. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 9(3): 558–565.

Glenberg, A.M., Sato, M., Cattaneo, L., Riggio, L., Palumbo, D., and Buccino, G. (2008). Processing abstract language modulates motor system activity. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 61(6): 905–919.

Graziano, M. (2006). The organization of behavioral repertoire in motor cortex. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 29: 105–134.

Hauk, O. and Pulvermüller, F. (2004). Neurophysiological distinction of action words in the fronto-central cortex. Human Brain Mapping, 21(3): 191–201.

Hauk, O., Johnsrude, I., and Pulvermüller, F. (2004). Somatotopic representation of action words in human motor and premotor cortex. Neuron, 41(2): 301–307.

Heilman, K.M., Rothi, L.J., and Valenstein, E. (1982). Two forms of ideomotor apraxia. Neurology, 32(4): 342–346.

Kemmerer, D., Castillo, J.G., Talavage, T., Patterson, S., and Wiley, C. (2008). Neuroanatomical distribution of five semantic components of verbs: evidence from fMRI. Brain and Language, 107(1): 16–43.

Kemmerer, D., Rudrauf, D., Manzel, K., and Tranel, D. (in press). Behavioral patterns and lesion sites associated with impaired processing of lexical and conceptual knowledge of actions. Cortex.

Kertesz, A. and Ferro, J.M. (1984). Lesion size and location in ideomotor apraxia. Brain, 107(3): 921–933.

Kollias, S.S., Alkadhi, H., Jaermann, T., Crelier, G., and Hepp-Reymond, M.C. (2001). Identification of multiple nonprimary motor cortical areas with simple movements. Brain Research Reviews, 36(2–3): 185–195.

Lakoff, G. and Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the Flesh: The Embodied Mind and its Challenge to Western Thought. New York: Basic Books.

Landau, A.N., Aziz-Zadeh, L., and Ivry, R.B. (2010). Modulations of the N170 component by semantic priming. Journal of Neuroscience, 30(45): 15254–15261.

Leiguarda, R.C. and Marsden, C.D. (2000). Limb apraxias: higher-order disorders of sensorimotor integration. Brain, 123(5): 860–879.

Preuss, T.M., Stepniewska, I., and Kaas, J.H. (1996). Movement representation in the dorsal and ventral premotor areas of owl monkeys: a microstimulation study. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 371(4): 649–676.

Pulvermüller, F., Hauk, O., Nikulin, V.V., and Ilmoniemi, R.J. (2005). Functional links between motor and language systems. European Journal of Neuroscience, 21(3): 793–797.

Rizzolatti, G. and Craighero, L. (2004). The mirror-neuron system. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 27: 169–192.

Rizzolatti, G., Gentilucci, M., Fogassi, L., Luppino, G., Matelli, M., and Ponzoni-Maggi, S. (1987). Neurons related to goal-directed motor acts in inferior area 6 of the macaque monkey. Experimental Brain Research, 67(1): 220–224.

Rothi, L.J., Heilman, K.M., and Watson, R.T. (1985). Pantomime comprehension and ideomotor apraxia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 48(3): 207–210.

Rueschemeyer, S.-A., Pfeiffer, C., and Bekkering, H. (2010). Body schematics: on the role of the body schema in embodied lexical-semantic representations. Neuropsvchologia, 48(3): 774–781.

Saygin, A.P., Wilson, S.M., Dronkers, N.F., and Bates, E. (2004). Action comprehension in aphasia: linguistic and non-linguistic deficits and their lesion correlates. Neuropsychologia, 42(13): 1788–1804.

Schubotz, R.I. and von Cramon, D.Y. (2003). Functional-anatomical concepts of human premotor cortex: evidence from fMRI and PET studies. Neuroimage, 20(Suppl. 1): S120–S131.

Schubotz, R.I., von Cramon, D.Y., and Lohmann, G. (2003). Auditory what, where, and when: a sensory somatotopy in lateral premotor cortex. Neuroimage, 20(1): 173–185.

Scorolli, C. and Borghi, A.M. (2007). Sentence comprehension and action: effector specific modulation of the motor system. Brain Research, 1130(1): 119–124.

Tettamanti, M., Buccino, G., Saccuman, M.C., Gallese, V., Danna, M., Scifo, P., Fazio, F., Rizzolatti, G., Cappa, S.F., and Perani, D. (2005). Listening to action-related sentences activates fronto-parietal motor circuits. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 17(2): 273–281.

Tranel, D., Kemmerer, D., Damasio, H., Adolphs, R., and Damasio, A.R. (2003). Neural correlates of conceptual knowledge for actions. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 20: 409–432.

van Dam, W., Rueschemeyer, S.-A., and Bekkering, H. (2010). How specifically are action verbs represented in the neural motor system: an fMRI study. Neuroimage, 53(4): 1318–1325.

Willems, R.M., Toni, I., Hagoort, P., and Casasanto, D. (2009). Body-specific motor imagery of hand actions: neural evidence from right- and left-handers. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 3: 39.

Willems, R.M., Hagoort, P., and Casasanto, D. (2010). Body-specific representations of action verbs: neural evidence from right- and left-handers. Psychological Science, 21(1): 67–74.