The relationship between gesture and language in brain-damaged patients and individuals with autism

GESTURE AND LANGUAGE PROCESSING

One of the earliest accounts of a study of language and gesture dates back over 400 years to a ruler named Abkus, Emporer of Hindustan, 1542–1605 (Bonvillian et al., 1997). Abkus isolated twenty ‘sucklings’ and ordered them to be raised by nurses who did not speak to them throughout their development and, after a period of years, the children were to be evaluated to determine what language they spoke. The results revealed that the children who did survive communicated not by spoken language, but by gesture alone. This experiment was very cruel, and one that would not be carried out today. The results, however, support the view that language is built upon a primitive gestural system (Allott, 2001), suggesting that language and gesture are intimately related and are indeed a ‘close family’ (Bates and Dick, 2002; see also Corballis, this volume).

Corroborations of the relationship between gestures and language have been provided by a series of studies carried out by Gentilucci and collaborators (Gentilucci et al., 2001, 2004; see also Gentilucci and Campione, this volume). Their studies showed that language and gesture share the same communication mechanism. To give rise to this hypothesis, they first demonstrated a relationship between hand and mouth (Gentilucci et al., 2001), then they considered the link between hand gestures and language (Gentilucci et al., 2004). In the first series of experiments, Gentilucci and colleagues (2001) reported on a relation between hand grip and mouth aperture (opening). Specifically, when subjects were asked to make a grasping movement with their fingers towards a large or a small object, and at the same time were asked to open their mouth independently of the size of the object, they reported a consistent increase of the mouth aperture, which was in relation to the size of the grip aperture (hand). This result was also replicated in a reversed way. Subjects were asked to open their mouth towards a small or a large object, and to make finger aperture independently of the mouth. Lip/grip opening was affected by object size, suggesting a mutual influence between the two motor programmes (for the mouth and the fingers) that are simultaneously activated. Hand–mouth relationship was further explored by Buccino et al. (2004), who showed that the observation of hand and mouth movements activates the BA 44 (Broca’s area). Broca’s area was not activated during the observation of foot movements, suggesting that the activation of Broca’s area when observing hand and mouth movements cannot be attributed solely to verbalization, but rather to a relationship between hand and mouth.

In this chapter, the first section will be dedicated to a review of the neuropsychological studies of patients with deficits in gestural processing, and the relationship between praxis profiles and patterns of language impairments will be elucidated. In the second section, a review of the development of gestures and language in typically developing children and individuals with autism will be presented. Finally, the relationship between gestural processing patterns and language in individuals with autism will be explored.

LIMB APRAXIA

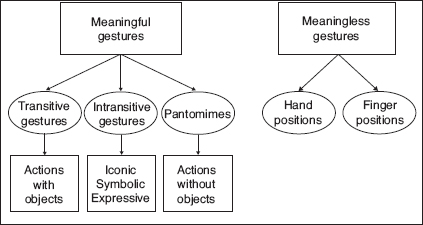

In cognitive neuropsychology, deficits in language processing in adults include aphasia (deficits in the production or comprehension of language), alexia (reading problems) and/or agraphia (difficulties in writing). A deficit in producing or comprehending gestures is described as limb apraxia. The term apraxia derives from the Greek language meaning a (without) and praxis (action). Limb apraxia is a specific form of apraxia defined as the deficit of purposive movements, which cannot be explained by elementary motor or sensory defect, by task comprehension problems or by inattention to command (De Renzi and Faglioni, 1999). Purposeful movements are distinguisthed in two main categories: meaningless and meaningful gestures. Meaningless gestures are gestures that carry no meaning for the examinee (e.g., fist under the chin). Three different types of meaningful gestures are traditionally tested in limb apraxia: transitive gestures – the actual manipulation and use of tools; intransitive gestures – gestures that convey expressive (e.g., ‘waving goodbye’) or symbolic (e.g., ‘military salute’) information; and pantomimes – the gestural description or ‘mime’ of tool use.

In the early twentieth century, Hugo Liepmann identified two main types of limb apraxia, ideational apraxia (IA) and ideomotor apraxia (IMA: Liepmann, 1920). To this day, this dichotomy still exists and is prevalent in the most recent literature on limb apraxia. However, these two praxis impairments are not agreed upon by limb apraxia experts. Some authors define IMA as a disorder of complex movements characterized by spatiotemporal errors in tool use, gesture pantomime and/or gesture imitation (Buxbaum et al., 2000; Rothi et al., 1991); while others report IMA as a deficit in gesture imitation only (Cubelli et al., 2000; De Renzi and Faglioni, 1999). IA is considered as an impairment of the performance of complex actions with objects (Buxbaum et al., 2000), or an impairment of the production of all meaningful gestures (transitive, intransitive and pantomimes: Cubelli et al., 2000). In this chapter, the definition of IMA and IA by De Renzi and Faglioni (1999) and by Cubelli et al. (2000) will be considered. More specifically, IMA is interpreted as a deficit in imitating gestures, and IA as a deficit in the production of meaningful gestures on command.

Cognitive models of limb apraxia

The relationship between language and gesture was investigated in one of the first papers published by Hugo Liepmann in 1905. Liepmann (1905) reviewed the data from 83 cases of patients classified as having either left or right brain damage, based on the side of their hemiplegia. He asked his patients to perform several tasks including imitating gestures, pantomiming the use of objects, performing symbolic gestures and using real objects. Liepmann did not identify signs of apraxia in any of the 42 right hemisphere-damaged patients. In contrast, 20 out of the 41 left hemisphere-damaged patients behaved similarly to what Liepmann defined as a ‘definite disturbance’, since they demonstrated deficits in performing the gestural tasks that he administered. These results led Liepmann to conclude that limb apraxia results from lesions in the left hemisphere rather than the right hemisphere. Since a lesion in the left hemisphere often impairs language functioning, it is common to find apraxic patients who have coexisting aphasia (see also De Renzi et al., 1980).

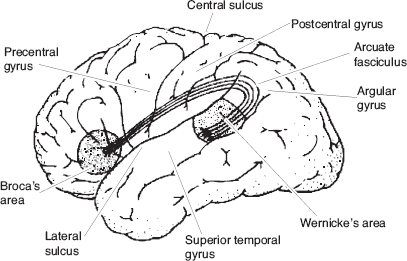

A more systematic approach to understanding language and action originating from the same neural system was provided by Geschwind (1965), who suggested that language elicits motor production using the same neural circuitry as Wernicke suggested for speech (Figure 15.1). He posited a hypothesis implicating a language and motor disconnection.

A disruption to the pathways connecting the motor association areas would, in fact, explain most apraxic disturbances according to Geschwind’s theory (see Heilman and Rothi, 1997, for review). Subsequently, various patterns of apraxia emerge depending on the area of disconnection. However, as more cases of apraxia were identified, Geschwind’s hypothesis failed to explain these newly identified patterns.

As an alternative to the Geschwind hypothesis (1965), Heilman et al. (1982) posited a representational hypothesis and were the first to suggest that there were ‘similarities between how the brain processes language and how the brain processes praxis’, comparing the gestural processing system to the modular processing systems of aphasia. Clearly, the classic dichotomy of ideomotor/ideational apraxia is not sufficient in explaining all of the dissociations reported in gesture production and imitation in patients with limb apraxia. Moreover, the interpretation of ideational and ideomotor apraxia according to Liepmann suggests that limb apraxia must be considered as a production deficit only; however, several cases have been reported of patients showing difficulties in tasks that do not require gesture production, including tasks of gestural recognition (Cubelli et al., 2000).

Figure 15.1 Geschwind Model (based on http://thebrain.mcgill.ca).

To account for the complexity of limb apraxia, several models have been posited (De Renzi, 1985; Rothi et al., 1991; Roy and Square, 1985). In particular, Rothi et al. (1991) proposed a model of praxis processing designed to separate the representations for gesture production and gesture reception. This new model was mapped on to a previously described cognitive model of language processing (Patterson and Shewell, 1987). Similar to the cognitive model for language processing, the authors proposed a dual route model of praxis processing that included a route for the processing of meaningful gestures (which pass through the long-term memory system storing the shape of all familiar gestures), and a direct route that allowed for the imitation of meaningless gestures, thereby bypassing meaning. This model marked a turning point in the understanding of gestural processing because it was the first to evaluate both the comprehension and production of gestures.

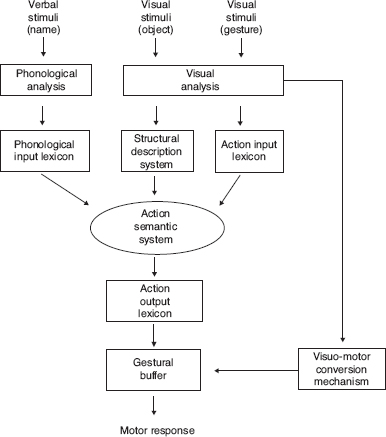

In 2000, Cubelli and colleagues modified Rothi et al.’s (1991) model and validated their version by testing 19 left brain-damaged patients (Cubelli et al., 2000). Differing from Rothi et al.’s model (1991), this model includes a visuo-motor conversion mechanism responsible for the production of meaningless gestures, which occurs by ‘transcoding visual information into motor programs’ (Cubelli et al., 2000: 148). This mechanism is similar to the graphemic/phonemic conversion mechanism of the model for reading processing. Cubelli et al.’s model includes an additional gestural memory buffer, equivalent to the phonological buffer in language models that ‘holds a short-term representation of the to-be-executed motor program’ (Cubelli et al., 2000: 148). See Figure 15.2 to view the cognitive model of praxis processing.

Figure 15.2 Cognitive model of praxis processing (Cubelli et al., 2000).

In line with Rothi et al.’s model (1991), the cognitive model of Cubelli et al. (2000) tests gestures across multiple modalities including visual modality for testing object use and gestures, and gesture production to verbal command. Furthermore, both models are based on the foundation of a language model. In particular, the action lexicon is similar to word recognition (input) and word production (output) in language processing models. As in the lexicon of language models, the lexicon in the cognitive model is based on the concept that there is a processing advantage for previously seen movements. This is analogous to language models in which there is a processing advantage for previously seen words with which the reader has had prior experience. The ‘form’ or representation of familiar gestures is stored in the long-term memory system of the gestural lexicon and therefore allows for gesture recognition. Again, this is akin to word recognition of language models. The output lexicon contains the procedural gestural knowledge and allows for production of all known gestures (Bartolo et al., 2003). The production component of the model contains the procedural knowledge of the action. Importantly, action requires the integration and coordination of both components: the conceptual and procedural knowledge held in the action semantic and action output respectively (Bartolo et al., 2003; Rothi et al., 1991). This is the difference between ‘knowing’ how an object should be used and actually having the recipe to use it. In everyday life we may know how an object should be used although we have no experience in using it (e.g., knowing how a kite should be used but not possessing the instructions to fly the kite: Bartolo, 2002; Bartolo et al., 2003).

Just as the ‘form’ is stored in long-term memory, the content of familiar gestures is stored in a long-term memory system of the action semantic system. Roy and Square (1985) suggested that a conceptual system included three kinds of knowledge: knowledge of objects and their functions; action knowledge; and knowledge of the sequencing of single actions. In addition to action knowledge, the semantic system also holds gestural meaning for pantomimes (e.g., the mime of object use) and intransitive gestures (e.g., communicative gestures: Bartolo, 2002). The visuo-motor conversion mechanism makes up the non-lexical route and is responsible for transforming visual information into motor action (Cubelli et al., 2000). The gestural buffer is similar to the phonological buffer in language models. The gestural buffer holds the motor programmes for both the lexical and non-lexical routes until the gestures are executed. It is the gestural buffer that allows for the time necessary to translate the abstract formations of gestures into accurate and timely sequences of motor commands necessary for ‘linked movement segments’ resulting in visible action (Cubelli et al., 2000: 147).

Deficits in language and gestural processing in adults

Theories on the evolution of the species claim that language originated from gesture, suggesting a strong relationship between the two (see also Corballis, this volume). However, in cognitive neuropsychology, when patients suffer from language or gesture deficits, to our knowledge little is done for simultaneously exploring language and gestures. This seems surprising given that the recent cognitive models of praxis processing (Cubelli et al., 2000; Rothi et al., 1991, 1997) are mapped on to the models of language comprehension and production (Patterson and Shewell, 1987; see also Coltheart et al., 2001). Furthermore, to date, experimental data on healthy subjects have shown a clear relation between language and transitive, intransitive and pantomime gestures (Bernardis and Gentilucci, 2006; Gentilucci et al., 2004). In this section, we will try to delineate the recent works carried out on limb apraxia, which are based on these recent cognitive models of praxis processing, in order to understand whether patterns of language processing are similar to those related to gesture processing. If there is a relationship between gesture and language, neuropsychological studies based on the cognitive models of limb apraxia should report patterns similar to those reported in the literature of language processing.

By looking at individuals diagnosed with dyslexia and apraxia, it is possible to see that they have similar cognitive profiles, as suggested by the fact that it is possible to map their gesture or language performance to similar cognitive models. If we suppose that meaningful gestures (transitive, intransitive and pantomimes) can be considered in relation to (meaningful) words, both regular and irregular, and meaningless gestures in relation to pseudo-words, it follows that both models predict patterns of dyslexia and limb apraxia that are complementary. A deficit at the level of the non-lexical route of language processing would result in difficulty in reading pseudo-words, with spared ability to read regular and irregular words (phonological dyslexia). An impairment in the same route for praxis processing would result in difficulty in imitating meaningless gestures, but not meaningful actions (ideomotor apraxia). Reversely, impairment along the lexical route would disrupt production of all meaningful gestures, but the capacity to imitate both meaningful and meaningless gestures should be spared, given the possibility of using the non-lexical route for imitation (ideational apraxia: Cubelli et al., 2000). The same suppositions hold for a deficit along the lexical route in the cognitive model of language processing. The capacity to read irregular words would be impaired; however, the capacity to read regular and pseudo-words would be spared (surface dyslexia).

Interestingly, not only are the profiles similar in both dyslexia and limb apraxia, but even when rare cases or patterns are reported in studies in language processing, rare cases or patterns are also reported in studies in praxis processing.

One such case in language processing is hyperlexia, defined as a specific ability of children to read aloud written words better than one would expect for their mental age (Snowling and Frith, 1986). In particular, Temple (1990) reported a child with hyperlexia, for whom accuracy in reading aloud irregular words was possible despite the absence of understanding of the meaning of these words. According to the models of reading aloud (Coltheart et al., 1980), irregular words cannot be read with accuracy using the phonological reading system, since for these words the graphemic–phonemic transformation would not be possible. In the absence of understanding of their meaning, this impoverished semantic knowledge of the words would suggest an impaired lexico-semantic reading system. This suggests the possible development of a direct reading system, within which words are recognized and abstract representations activate phonological representations for the pronunciation of the whole words, without ever activating meaning.

In parallel, cases of normal gesture production (pantomime) in the absence of object identification have been reported in patients with limb apraxia. Riddoch and Humphreys (1987) discussed the case of a patient with optic aphasia, JB, who was poor at both naming and accessing detailed semantic information about objects from visual input but who could make the pantomimes of the same stimuli. For instance, JB could make cutting and prodding gestures in relation to the observation of a knife on one occasion and a fork on another. However, when he was asked to decide which two objects were most related to each other, for instance matching together a knife and fork and rejecting a plate, he incorrectly pointed to the fork and the plate. His difficulty was modality specific and affected the visual input only; indeed, he could access the meaning of the object through the verbal modality. The authors argued that JB’s relatively preserved ability to make pantomimes in response to visually presented objects was due to the operation of a direct route to action that bypassed the semantic system. In particular, this is similar to what happens in hyperlexia; this case would indicate that a separate direct visual route to action operates independently of a semantic route. To account for hyperlexia, it has been proposed that there is a possible development of a direct reading system. Similarly, for cases like that of JB, Riddoch and Humphreys (1987) proposed the use of a direct visual route to action. This direct route to action was based on associations between stored visual representations of objects and learned actions, within which words are recognized. Abstract representations activate phonological representations for the pronunciation of the whole words, without ever activating meaning. These stored visual representations could be represented in a structural description system separate from semantic memory. Rothi et al. (1991), in their cognitive model, included this direct route, linking the stored structural knowledge about objects to the patterns of stored actions. Cubelli et al. (2000) reject the notion that it is possible to produce a gesture in the absence of semantic knowledge; therefore they did not include this route in their model (Cubelli et al., 2000). They also state that, in order to confirm such a pattern that we can call ‘hyperpraxia’, the patient should show intact ability to reproduce familiar gestures for which the meaning is unknown, but should not be able to reproduce unfamiliar gestures.

Another study showing the relationship between a cognitive deficit in language and gesture processing has been reported by Bartolo et al. (2001). The authors reported on the case of a patient, MF, who presented with a clear impairment in the production and imitation of all meaningful gestures (pantomimes, intransitive and transitive gestures) to be performed under different modalities of presentation (verbal, visual and imitation). Nevertheless, MF’s ability to imitate meaningless gestures was flawless. According to the model (Cubelli et al., 2000), the imitation of meaningful gestures could be processed using the lexical or the non-lexical route, so it was unclear as to why MF did not use the spared non-lexical route to imitate meaningful gestures. According to the authors, this result can be interpreted by suggesting that, once a gesture is recognised as familiar (spared input lexicon), it is processed using the lexical route, even though a deficit in (or in accessing) the output lexicon (production) is present. This result is similar to what has been reported in the literature of language processing (Bartolo et al., 2001). In particular, Margolin (1984) suggested two cognitive strategies to correctly copy written words: the lexical procedure and the pictorial procedure (non-lexical route). When using the lexical procedure, one reads the word and reproduces it as if writing under dictation; whereas by using the pictorial procedure the word is copied point to point as if it were a meaningless pattern. However, if the word to be copied is recognized as familiar, the lexical route is activated by default, preventing the implementation of the pictorial strategy. Similarly, the use of the non-lexical route to imitate a shown gesture recognized as familiar would automatically activate the input lexicon, leading to the selection of the correspondent motor programme within the lexical route (Bartolo et al., 2001).

Taken together, neuropsychological results of these studies suggest that language and gesture are processed in similar ways; however, this does not provide evidence of a relationship between language and praxis abilities if it is not demonstrated that a deficit in language processing is followed by a similar deficit in praxis processing. We recently tested a small group of children with (constructional) dyspraxia and dyslexia on a series of tasks assessing both reading and gesture processing. A battery of tasks taxing the lexical and non-lexical routes for gesture and language processing has therefore been devised. Let’s now consider that what is supposed to happen in evolution, happens also in the development of language and gesture across the lifespan. If language and gestures are related, or better, if, as suggested by Corballis (2009), language originated from gestures, we should expect to find that children with deficits in gestural processing also have difficulties in processing language (in this case reading). Results, although preliminary, support this hypothesis. All the children with difficulties in processing gestures showed difficulties at some stages of reading processing, whereas some dyslexic children did not show signs of gesture deficits (Dewaele, 2011).

In the next session, praxis and language abilities in typically developing children and individuals with autism will be discussed.

GESTURE DEVELOPMENT IN TYPICALLY DEVELOPING CHILDREN

The study of gesture in children provides a unique opportunity to peer into the window of parallel systems, including the development of language and action. The first speech–gesture link that appears to develop is the onset of canonical babbling together with the onset of rhythmic hand banging (see also Gentilucci and Campione, this volume). Canonical babbling is defined by Oller et al. (1998) to be well-formed syllables containing a ‘vowel-like’ and a ‘consonant-like’ element, such as /dada/, /ba/ and /dIdI/. This form of babbling is an important milestone, usually achieved in typically developing children between 6 and 8 months of age. Failure to produce canonical babbling by 10 months is a strong predictor of delays in word acquisition and word combinations in the second year (Paul, 2001). Ejiri and Masataka (2001) published their findings of the co-occurrence of vocal behaviours together with motor actions in 6- to 11-month-old infants studied for four months in the prelinguistic stage. The authors found that vocalizations co-occurred together with rhythmic actions, especially in the stage preceding canonical babbling onset. As a follow-up study, they conducted acoustic analysis that revealed that the vocalizations that co-occurred with the rhythmic actions were, in fact, similar to mature speech (rapid transitions and short syllables), thereby leading the researchers to the hypothesis that the rhythmic hand banging may, in actuality, contribute to the infant’s ability to perform articulatory actions that are necessary for spoken language acquisition. Therefore, canonical babbling does not appear to develop in isolation, but rather appears to be closely linked to rhythmicity of behaviour, which is action (Ejiri and Masataka, 2001).

The use of gesture has been reported to correlate with word comprehension, to predict expressive language development and to facilitate syntactic development in language production. In typical development, the first signs of word comprehension emerge between 8 and 10 months of age and it is around this same time that children begin to produce actions associated with objects in their environment. For example, the child may put a cup to his or her lips for ‘drink’. This gesture/action pair has also been termed gestural naming, or a recognitory gesture. These early gestures are critical to child language development because they precede first words and they soon co-occur with the production of first words (e.g., a child will point to a ball and say ‘ball’ at the same time). When a child says the same word as the intended gesture, this speech-gesture combination is known as a complementary gesture (McEachern and Haynes, 2004). Shore and colleagues (1990) outline several lines of evidence suggesting that these early gestures are a form of naming. Shore et al. (1990) show that recognitory gestures and naming emerge at the same time, that gestures and naming are positively correlated, and that these gestures and first words are similar in content. Interestingly, this correlation between gestural naming and word production is evident in typically developing children at only around 12 to 18 months (Bates and Dick, 2002; Paul, 2001; Shore et al., 1984). Bates and Dick (2002) suggest that, once language develops sufficiently, the more primitive gestural symbol system is no longer necessary, and the child then relies solely on verbal communication. Therefore, this correlation would only be evident when the child is developing early words, but not after the child is communicating in multi-word combinations. That is, ‘once children have cracked the code and entered into the richly cross-referenced cue structure of a real natural language, the pace of word learning increases exponentially, and eclipses the meager system of gestural symbols’ (Bates and Dick, 2002: 3).

The developmental trajectory of speech and gesture is tightly coupled, and gesture production has been explored in relation to future expressive language ability in children as young as 14 months. In one study, children’s gesture use at age 14 months was shown to be a positive predictor of expressive vocabulary at 42 months (Rowe et al., 2008). The authors suggested that gesture and vocabulary are influenced in two different directions: the first through the use of gestures that the children themselves produce; and the second through gestures that the parents produce that are directed towards the children (Rowe et al., 2008). Children with parents who gestured ‘a great deal’ also gestured more and developed larger verbal vocabularies than children with parents who did not gesture often.

Language and action in developmental neuropsychology

Similar to adult patient populations, the relationship between gesture and language and the relationship between language development and the development of motor control is an area of increasing interest in paediatric research (Iverson, 2010). ‘There is a relationship between motor development and language development, but it is complex and multi-faceted rather than simple and directional’ (Iverson, 2010: 258). In developmental neuropsychology, gesture refers to the ability to perform skilled actions and the ability to use tools (Dewey, 1995). Hence, developmental neuropsychologists define dyspraxia as a disorder in gestural performance resulting in deficits in representational (e.g., meaningful) and non-representational gestures (e.g., meaningless: Dewey, 1995; Dewey et al., 2007). In 1985, Cermak reviewed previous research in developmental dyspraxia and observed that the performance of different parameters was not being tested in children as it was in adults. Understandably, children are still developing, but while adults can be assessed in terms of pathological and non-pathological performance, children’s praxis skills need to consider modality-specific developmental standards. Children with developmental dyspraxia are often described in general terms as ‘clumsy’ or uncoordinated. Cermak (1985) stressed the importance of the need to develop a psychometric tool to assess developmental norms of praxis processing, spanning the age ranges into adulthood and assessing children with developmental disorders in a comprehensive fashion, just as adults with limb apraxia were being evaluated.

Language and action in autism spectrum disorders

One area of growing interest in the understanding of the relationship between language and gestural processing is the autism spectrum disorders. Autism is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by a ‘triad of impairments’ in the areas of social interaction, language and communication, and restrictive, repetitive and stereotypical patterns of behaviour (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Since the time of Kanner, gestural impairments in autism have been reported. Kanner (1943) published a description of a child from his original research: ‘Her expression was blank, though not unintelligent, and there were no communicative gestures’ (p. 240). One of the greatest sources of communication difficulty families and caregivers face when dealing with preverbal autistic children is that they do not compensate for their language deficit through the use of functional gestures, failing to spontaneously use conventional gestures to make their needs known (Woods and Wetherby, 2003). In autism, individuals may present with a disorder of gesture, a language disorder, or a combination of both, and this gesture–language link may be disrupted at any level. For the aforementioned reasons, fractionations within the gestural system will be highlighted in a group of individuals with autism in this chapter.

Testing language and action in autism spectrum disorders

In order to assess gestural processing in a population of high-functioning individuals with high-functioning autism and Asperger’s syndrome, a new battery of tasks was developed – the Apraxia Battery for children and adolescents. This new battery was based on tests used in adult apraxia research (Bartolo, 2002; Bartolo et al., 2008; Buxbaum et al., 2005; Goldenberg, 1999), but was substantially altered to make the tasks appropriate and engaging for the target developmental group. In the present battery, age-appropriate objects and gestures were presented using videoclips as stimuli and objects were tested both in direct imitation and in novel use modalities. Tasks assessing the imitation of meaningless gestures and the recognition, comprehension, production and imitation of meaningful gestures have been included (Figure 15.3).

Results of 19 children with either Asperger’s syndrome or high-functioning autism were reported in a series of studies (Stieglitz Ham et al., 2008, 2010, 2011). Twenty-three typically developing children were matched to the ASD group for age (range 7–15, mean 12; SD 2.1), gender, verbal intelligence (VIQ), performance intelligence (PIQ) and full-scale intelligence (FSIQ). IQ was measured using the Wechsler Abbreviated Scales of Intelligence (Wechsler, 1999).

Body part orientation errors

Meaningless gesture imitation was assessed using two tasks: imitation of hand postures and imitation of finger positions. The participants viewed ten hand posture stills and ten finger positions, which they were asked to imitate. The results revealed that the individuals with autism performed the imitation tasks more poorly than the controls, and the reason behind the failures was further explored. In this experiment, in order for body orientation to be considered correct, the imitation attempt had to be produced in the same position in relation to the various body parts of the person in the still photo. An interesting error pattern emerged; specifically, body part orientation errors significantly predicted group membership (Stieglitz Ham et al., 2008). One hypothesis that may explain these findings is found in the Self–Other Mapping Model of Rogers and Pennington (1991). Rogers and Pennington (1991) suggest that individuals with autism have difficulty ‘seeing others as a template of the self’. In other words, an impairment in imitation from infancy may affect bodily synchrony and mutual coordination. This dysynchrony, in turn, may affect the ability of the infant to coordinate both emotionally and physically with the caregiver, resulting in a deficit in self and other awareness. A deficit in self and other awareness and intersubjectivity would affect language in various ways. Rogers and Pennington (1991) suggest that echolalia may be a form of an alternative route to language learning, a way of learning language in the presence of an intersubjective deficit. In the case of echolalia, words are learned through associations and experiences with the environment, not in joint attention interactions. For example, a child may hear ‘Do you want juice?’ when he is given juice. Later, the child may say ‘Do you want juice?’ when he is thirsty, as a form of request. The authors suggest that pronoun errors may also be a manifestation of a deficit of shared meaning. If a child uses associative learning as a way to learn pronouns, pronoun reversals will result. Kanner described a pronoun reversal as one in which pronouns are repeated verbatim, with a failure to change the pronoun based on the perspective (Kanner, 1943).

Figure 15.3 Meaningful and meaningless gesture hierarchy.

Recently, Hobson et al. (2010) suggested that interpersonal communication requires the awareness of self and other and that this intricate concept is reflected in deictic terms and gestures, including the appropriate use of pronouns. Hobson and colleagues (2010) cited Kanner’s description of an example of pronoun reversal. For example, if a mother tells a child, ‘Now I will give you your milk’ and the child uses echolalia, consequently the child will come to speak of herself as ‘you’ and the other person as ‘I’. However, Hobson et al. (2010) point out that Kanner also described children’s inability to adjust to the ‘altered situation’ and that the use of inappropriate pronouns based on the speaker roles may ‘implicate the children’s limited engagement in the stances of other people’ (Hobson et al., 2010: 404). In sum, Hobson and colleagues (2010) suggest that children with autism may experience difficulty identifying with the ‘orientation-in-speaking of other persons’ and show atypical pronoun usage. Subsequently, body part orientation errors may also be a result of this same underlying deficit.

Dissociation between pantomimes and intransitive gestures

Bates and Dick (2002) noted that puzzling dissociations have ‘emerged between language and gesture, and between perception and action within language itself’ (p. 7). They suggested that dissociations might come apart in tasks of perception and action. At the time, the authors were unaware of any studies that tested elicited imitation across production and comprehension tasks in a developmental disorder. Dissociations in gesture performance have been well documented in adults with limb apraxia and fractionations within the gestural system in developmental disorders are currently being investigated (Hamilton, 2008; Stieglitz Ham et al., 2010, 2011). Interesting patterns of dissociations have been identified in studies by Stieglitz Ham and colleagues (2010) and will be discussed in turn.

JK (11-year-old male) was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) according to DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria and was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome. Gestural processing was evaluated by means of 12 tasks assessing gesture comprehension and production (Stieglitz Ham et al., 2010). Gesture comprehension was assessed using three separate matching tasks. For transitive gesture comprehension the participants were instructed to point to a picture of the object that was the most strongly associated with the target photo (e.g., book matched to backpack instead of desk). In the intransitive gesture task the participants observed the examiner producing a gesture and then matched the gesture to one of four photos of social scenarios (e.g., ‘stop’ gesture matched to the social scenario of a student running in the hallway). Similarly, participants viewed a target pantomime and matched the gesture to the correct photo (e.g., ‘brushing teeth’ gesture matched to toothbrush). Gesture production was assessed by means of five tasks assessing transitive gestures (object use) and the production of pantomimes and intransitive gestures in verbal and visual modality. In the pantomime production task, the participants were required to listen to the name of an object (verbal modality) or to view a real object and then to pantomime its use. Intransitive gestures were elicited after the participant listened to the description of (verbal modality) or watched a video of (visual modality) a social scenario. Imitation was assessed by means of four tasks testing the reproduction of transitive, intransitive, meaningless and pantomime gestures.

JK performed within normal limits in both gesture comprehension and imitation. Production of pantomimes and transitive gestures was also performed within normal limits. Although the TD (typically developing) group also showed higher scores in the production of pantomimes than in that of intransitive gestures, JK scored well below cut-off in the production of intransitive gestures in both verbal and visual modalities, showing for the first time a dissociation between intransitive gestures (impaired) and pantomimes (well executed). This dissociation was confirmed by Crawford and Garthwaite’s (2005) statistical method: JK’s pantomime production was statistically dissociated from that of intransitive gestures in both the verbal and visual modalities.

Whereas consistent findings show an advantage in the production of intransitive gestures over pantomimes (Bartolo et al., 2003; Carmo and Rumiati, 2009; Mozaz et al., 2002), JK is the first report of a selective deficit in the production of intransitive gestures, thus differing from previous studies reporting production deficits in both pantomimes and intransitive gestures (Rogers et al., 1996; Smith and Bryson, 2007). This pattern of production (poorer intransitive gesture performance) cannot be explained by arguing that intransitive gestures based on a storytelling task may be too complex for an autistic participant. Indeed, JK had an intact cognitive profile; in particular his language comprehension skills were adequate for following verbal instructions, participating in functional conversation, and completing a test of listening recall, all within normal limits. Moreover, his verbal IQ score was well above cut-off. This finding weakens the plausibility of attributing the impairment of gestural performance to a pure language comprehension deficit. Finally, JK was also able to comprehend the visual social scenario, since he could match a gesture to the correct situation, suggesting that his impaired socio-cognitive abilities did not affect his capacity to understand gestures. To understand the nature of JK’s performance pattern, it is worth noticing that, during conversational speech, JK demonstrated a reduced capacity to integrate gestures into social communication, and although his ‘I don’t know’ responses in the production of intransitive gesture task predominated, at times he also expressed correct knowledge of the gesture to be executed, further confirming this difficulty in integrating the appropriate gesture (action) in the specific context.

Research into gesture and language studies may inform this pattern of production. A deficit in the production of intransitive gestures paired with the lack of integration of social gestures in conversation may have negative consequences on JK’s narrative discourse success. Not only have gestures been shown to improve students’ (i.e., listeners’) comprehension twofold when gesture was accompanied by speech instruction (teachers used gesture together with speech: Church et al., 2004), but gesture has also been shown to facilitate lexical retrieval for the speaker (Morsella and Krauss, 2004). Morsella and Krauss (2004) suggest that lexical gestures participate in speech production by increasing semantic activation of words, hence facilitating retrieval of the word form. In other words, the use of gesture aids in comprehension for the listener and aids in word retrieval for the speaker. Therefore, JK’s lack of conversational gesture coupled with his lack of production of social gestures may negatively impact his communicative effectiveness both by decreasing his semantic activation during discourse production and by decreasing the listener’s comprehension of the narrative if gesture is not paired with speech. The combination of the two processes may lead to impairment in social communication and social interaction – two core deficits in ASD.

The theory of underconnectivity and a unique praxis processing pattern

JK was an example of a case study within a larger group study. In addition to JK’s findings, the group results of the same study revealed an interesting error pattern in the ASD group that, to our knowledge, had not been identified before in the autism or apraxia literature. In particular, the individuals with autism often provided a correct verbal response to a social scenario without generating a gesture. This error, coined ‘verbal response only’, is a unique type of error that was evidenced only in the ASD group. This error type captures a phenomenon that we suggest is related to a disconnection of language and action and one that may be related to deficits in social cognition (Stieglitz Ham et al., 2010). In other words, JK was able to name the gesture required for a social scenario; however, he could not perform this same gesture, suggesting a disconnection between verbal and praxis abilities. This disconnection may actually be caused by a deficit in social cognition that, in turn, affected his ability to retrieve the conceptual representation (e.g., idea) of the action. It is worth noting that the opposite pattern occurred in a patient JB, diagnosed with optic aphasia, who was able to produce gestures (in this case pantomimes) but was unable to provide the name of the object used for the gesture (Riddoch and Humphreys, 1987).

Next, theoretical accounts to explain this unique pattern of producing a verbal response without generating a gestural response were explored. Williams and colleagues found that, in tasks of discourse processing (e.g., reading stories requiring different levels of inferencing in language tasks), the individuals with autism used a processing pattern for discourse that the typically developing controls only used for the most difficult condition (Mason et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2007). Namely, the individuals with autism activated the right hemisphere homologues (right temporo-parietal junction) for all three conditions, even the easiest tasks requiring the processing of physical inferences. In contrast, the authors found that the typically developing control group only activated the right hemisphere homologues when the task was complex, requiring higher-level abstract inferencing. These findings show that individuals with autism do activate the right hemisphere regions, but they demonstrate an inefficient processing pattern (Mason et al., 2008).

These current findings may prove to be an extension of the underconnectivity theory (Just et al., 2004), describing a disconnection of language and action and suggesting that this unique processing pattern of providing a verbal response only, and not providing a gestural response, may be the result of a disruption of connectivity or disconnection across brain regions. The underconnectivity of brain regions may also affect the synthesis and processing of various types of information, in particular demands in information processing that require integration and coordination across multiple domains. In this current gestural processing task, this theory suggests that the individuals with autism may have been at their limit in terms of their ability to coordinate multiple levels of information, including language and action, and the default response resulted in a verbal response only, which required less coordination to produce.

Following the disconnection theory, another possibility of explaining JK’s ‘verbal response only’ pattern is to consider research in cognitive embodiment–the idea that many types of cognitive processing, including language, are grounded in perception and action (Meteyard et al., in press). Mahon and Caramazza (2008) suggest that ‘semantic content is grounded by interaction with sensory and motor information’ (p. 60). The authors explain that, once a concept is understood or realized, passive activation of both sensory and motor information subsequently follows this realization. JK verbally provided the name of the correct gesture without actually producing the action itself; he could not produce the gesture. It appears that JK realized the concept but a disconnection ensued and the sensory and motor information systems were not activated. Mahon and Caramazza (2008) further their argument by suggesting that disrupting the sensory or motor systems would, in turn, result in an impoverished realization of a concept. In this view, ‘sensory and motor information contributes to the “full” representation of a concept’ (Mahon and Caramazza, 2008: 68; see also Coello and Bartolo, this volume; Taylor and Zwaan, this volume). If the activation of sensory and motor systems indeed complements conceptual representations as the authors suggest, this would provide insight into JK’s deficits in social cognition as well. Although JK did demonstrate understanding of the basic concept, he was unable to activate the sensory and motor systems of the gesture, thereby losing the deeper conceptual realization that the sensory and motor systems provide. This, in turn, resulted in the diminished realization of the concept, or an impoverished concept as the authors suggest. In individuals with autism, we argue that they are unable to gain the full benefit of conceptual representations using sensory and motor system feedback, resulting in a decreased expression of social information in social contexts. Deficits in social cognition and social communication are core deficits in ASD, and a deficit in secondary embodiment may be one possible explanation for these impairments.

CONCLUSIONS

Although it is far from being a comprehensive review, an attempt to chronicle the relationship between language and action across the lifespan was proposed. This chapter described behavioural studies showing that, in adults, language and gesture share the same communication mechanism. Next, the relationship between language and gesture in neuropsychology was reviewed. This important relationship between language and gesture was investigated by describing models of praxis processing that were mapped on to models of word comprehension and production and by reviewing reported profiles of praxis and dyspraxic deficits in single cases of patients. We also proposed a short review of the research in typical and atypical development in children. The progression of gesture development from the co-occurrence of gesture in speech in young infants to the use of gesture preceding speech was examined. Finally, results describing gestural production deficits in individuals with autism spectrum disorder were discussed in order to show how the relationship between gesture and language might affect social communication and social cognition.

A thorough understanding of the relationship between gesture and language may inform therapeutic interventions that will help improve not only specific difficulties in language and gesture processing, but also communicative effectiveness for both paediatric and adult patient populations.

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Revised Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). Washington, DC: APA.

Allott, R. (2001). The Great Mosaic Eye: Language and Evolution, Brighton: Book Guild.

Bartolo, A. (2002). Apraxia: new tests for the assessment of a cognitive model and the evaluation of the semantic system. PhD thesis, Aberdeen University.

Bartolo, A., Cubelli, R., Della Sala, S., Drei, S. and Marchetti, C. (2001). Double dissociation between meaningful and meaningless gesture reproduction in apraxia. Cortex, 37: 696–699.

Bartolo, A., Cubelli, R., Della Sala, S. and Drei, S. (2003). Pantomimes are special gestures which rely on working memory. Brain and Cognition, 53: 483–494.

Bartolo, A., Cubelli, R. and Della Sala, S. (2008). Cognitive approach to the assessment of limb apraxia. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 0: 1–19.

Bates, E. and Dick, F. (2002). Language, gesture, and the developing brain. Developmental Psychobiology, 40: 293–310.

Bernardis, P. and Gentilucci, M. (2006). Speech and gesture share the same communication system. Neuropsychologia, 44(2): 178–190.

Bonvillian, J.D., Garber, A.M. and Dell, S.B. (1997). Language origin accounts: was there gesture in the beginning? First Language, 17(51): 219–239.

Buccino, G., Vogt, S., Ritzl, A., Fink, G.R., Zilles, K., Freund, H.J. and Rizzolatti, G. (2004). Neural circuits underlying imitation learning of hand actions: an event-related fMRI study. Neuron, 42(2): 323–334.

Buxbaum, L.J., Veramontil, T. and Schwartz, M.F. (2000). Function and manipulation tool knowledge in apraxia: knowing ‘what for’ but not ‘how’. Neurocase: The Neural Basis of Cognition, 6(2): 83–97.

Buxbaum, L. J., Kyle, K. and Menon, R. (2005). On beyond mirror neurons: internal representations subserving imitation and recognition of skilled object-related actions in humans. Cognitive Brain Research, 25(1): 226–239.

Carmo, J.C. and Rumiati, R.I. (2009). Imitation of transitive and intransitive actions in healthy individuals. Brain and Cognition, 69: 460–464.

Cermak, S. (1985). Developmental dyspraxia, in Roy. E.A. (ed.), Neuropsychological Studies of Apraxia and Related Disorders (pp. 225–248). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Church, R.B., Ayman-Nolley, S. and Mahootian, S. (2004). The role of gesture in bilingual education: does gesture enhance learning? International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 7(4): 303–319.

Coltheart, M., Patterson, K. and Marshall, J.C. (eds) (1980). Deep Dyslexia. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Coltheart, M., Rasile, K., Perry, C., Langdon, R. and Ziegler, J. (2001). DRC: a dual route cascaded model of visual word recognition and reading aloud. Psychological Review, 108(1): 204–256.

Corballis, M.C. (2009). Comparing a single case with a control sample: correction and further comment. Neuropsychologia, 47(1): 2696–2697.

Crawford, J.R. and Garthwaite, P.H. (2005). Detecting dissociations in single-case studies: type I errors, statistical power and the classical versus strong distinction. Neuropsychologia, 44(12): 2249–2258.

Cubelli, R., Marchetti, C., Boscolo, G. and Della Sala, S. (2000). Cognition in action: testing a model of limb apraxia. Brain and Cognition, 44: 144–165.

De Renzi, E. (1985). Methods of limb apraxia examination and their bearing on the interpretation of the disorder, in Roy, E.A. (ed.), Neuropsychological Studies of Apraxia and Related Disorders (pp. 45–64). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

De Renzi, E. and Faglioni, P. (1999). Apraxia, in Denes, G. and Pizzamiglio, L. (eds), Handbook of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology (pp. 421–440). Hove: Psychology Press.

De Renzi, E., Motti, F. and Nichelli, P. (1980). Imitating gestures: a quantitative approach to ideomotor apraxia. Archives of Neurology, 37: 6–10. Dewaele, J. (2011). Lien entre geste et langage. Elaboration d’une batterie de tâches gestuelles et langagières proposée aux enfants dyspraxiques et/ou dyslexiques. Unpublished Masters dissertation, Université de Savoie.

Dewey, D. (1995). What is developmental dyspraxia. Brain and Cognition, 29(3): 254–274.

Dewey, D., Cantell, M. and Crawford, S. (2007). Motor and gestural performance in children with autism spectrum disorders, developmental coordination disorder, and/or attention hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 13: 246–256.

Ejiri, K. and Masataka, N. (2001). Co-occurences of preverbal vocal behavior and motor action in early infancy. Developmental Science, 4(1): 40–48.

Gentilucci, M., Benuzzi, F., Gangitano, M. and Grimaldi, S. (2001). Grasp with hand and mouth: a kinematic study on healthy subjects. Journal of Neurophysiology, 86(4): 1685–1699.

Gentilucci, M., Stefanini, S., Roy, A.C. and Santunione, P. (2004). Action observation and speech production: study on children and adults. Neuropsychologia, 42(11): 1554–1567.

Geschwind, N. (1965). Disconnexion syndromes in animals and man. Brain, 88: 237–294.

Goldenberg, G. (1999). Matching and imitation of hand and finger postures in patients with damage in the right or left hemispheres. Neuropsychologia, 37: 559–566.

Hamilton, A. (2008). Emulation and mimicry for social interaction: a theoretical approach to imitation in autism. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 61: 101–115.

Heilman, K.M. and Rothi, L.J. (1997). Limb apraxia: a look back, in Rothi, L.G. and Heilman, K.M. (eds), Apraxia: The Neuropscyhology of Action (pp. 7–156). Hove: Psychology Press.

Heilman, K.M., Rothi, L.J. and Valenstein, E. (1982). Two forms of ideomotor apraxia. Neurology, 32(4): 342–346.

Hobson, R.P., García-Pérez, R.M. and Lee, A. (2010). Person-centred (deictic) expressions and autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(4): 403–415.

Iverson, J.M. (2010). Developing language in a developing body: the relationship between motor development and language development. Journal of Child Language, 37(2): 229–261.

Just, M.A., Cherkassky, V.L., Keller, T.A. and Minshew, N.J. (2004). Cortical activation and synchronization during sentence comprehension in high-functioning autism: evidence of underconnectivity. Brain, 127: 1811–1821.

Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic disturbances in affective contact. Nervous Child, 2: 217–250.

Liepmann, H. (1905). Der weitere Krankheitsverlauf bei dem einseitig Apraktischen und der Gehirnbefund auf Grund von Serienschnitten. Monatsschrift fur Psychiatrie und Neurologie, 17: 289–311.

Liepmann, H. (1920). Apraxia Ergebnisse der Medizinischen Gesellschaft.

McEachern, D. and Haynes, W.O. (2004). Gesture–speech combinations as a transition to multiword utterances. American Journal of Speech Language Pathology, 13(3): 227–235.

Mahon, B.Z. and Caramazza, A. (2008). A critical look at the embodied cognition hypothesis and a new proposal for grounding conceptual content. Journal of Physiology: Paris, 102: 59–70.

Margolin, D.I. (1984). The neuropsychology of writing and spelling: semantic, phonological, motor, and perceptual processes. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 36A: 459–489.

Mason, R.A., Williams, D.L., Kana, R.K., Minshew, N. and Just, M.A. (2008). Theory of mind disruption and recruitment of the right hemisphere during narrative comprehension in autism. Neuropsychologia, 46(1): 269–280.

Meteyard, L., Rodriguez Cuadrado, S., Bahrami, B. and Vigliocco, G. (in press). Coming of age: a review of embodiment and the neuroscience of semantics. Cortex.

Morsella, E. and Krauss, R.M. (2004). The role of gestures in spatial working memory and speech. American Journal of Psychology, 117: 411–424.

Mozaz, M., Gonzalez Rothi, L.J., Anderson, J.M, Crucian, G.P. and Heilman, K.M. (2002). Postural knowledge of transitive pantomimes and intransitive gestures. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 8: 958–962.

Oller, D.K., Eilers, R., Neal, A.R. and Cobo-Lewis, A.B. (1998). Late onset canonical babbling: a possible early marker for abnormal development. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 103: 249–263.

Patterson, K.E. and Shewell, C. (1987). Speak and spell: dissociations and word class effects, in Coltheart, M., Sartori, G. and Job. R. (eds), The Cognitive Neuropsychology of Language (pp. 273–294). Hove: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Paul, R. (2001). Language Disorders from Infancy through Adolescence: Assessment and Intervention. Austin, TX: ProEd.

Riddoch, M.J. and Humphreys, G.W. (1987). Visual object processing in a case of optic aphasia: a case of semantic access agnosia. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 4: 131–185.

Rogers, S.J. and Pennington, B. (1991). A theoretical approach to the deficits in infantile autism. Development and Psychopathology, 3: 137–162.

Rogers, S.J., Bennetto, L., McEvoy, R. and Pennington, B. (1996). Imitation and pantomime in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Child Development, 67: 2060–2073.

Rothi, L.J., Ochipa, C. and Heilman, K. (1991). A cognitive neuropsychological model of limb praxis. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 8: 443–458.

Rowe, M.L., Ozcaliskan, S. and Goldin-Meadow, S. (2008). Learning words by hand: gesture’s role in predicting vocabulary development. First Language, 28(2): 182–199.

Roy, E.A. and Square, P.A. (1985). Common considerations in the study of limb, verbal, and oral apraxia, in Roy, E.A. (ed.), Neuropsychological Studies and Related Disorders (pp. 111–162). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Shore, C., O’Connell, B. and Bates, E. (1984). First sentences in language and symbolic play. Developmental Psychology, 20: 872–880.

Shore, C., Bates, E., Bretherton, I., Beeghly, M. and O’Connell, B. (1990). Vocal and gestural symbols: similarities and differences from 13 to 28 months, in Volterra, V. and Erting, C. (eds), From Gesture to Language in Hearing and Deaf Children (pp. 79–91). New York: Springer.

Smith, I. and Bryson, S. (2007). Gesture imitation in autism: II. symbolic gestures and pantomimed object use. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 24: 1–22.

Snowling, M. and Frith, U. (1986). Comprehension in ‘hyperlexic’ readers. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 42(3): 392–415.

Stieglitz Ham, H., Corley, M., Rajendran, G., Carletta, J. and Swanson, S. (2008). Brief report: imitation of meaningless gestures in individuals with Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38: 569–573.

Stieglitz Ham, H., Bartolo, A., Corley, M., Swanson, S. and Rajendran, G. (2010). Case report: selective deficit in the production of intransitive gestures in an individual with autism. Cortex, 46(3): 407–409.

Stieglitz Ham, H., Bartolo, A., Corley, M., Rajendran, G., Szabo, A. and Swanson, S. (2011). Exploring the relationship between gestural recognition and imitation: evidence of dyspraxia in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41: 1–12.

Temple, C.M. (1990). Auditory and reading comprehension in hyperlexia: semantic and syntactic skills. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 2: 297–306. Wechsler, D. (1999). Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI). New York: The Psychological Corporation.

Williams, D.L., Kana, R.J., Mason, R., Minshew, N.J. and Just, M.A. (2007). A Functional MRI Study of Lexical Ambiguity in High-functioning Autism. Boston, MA: American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

Woods, J. and Wetherby, A.M. (2003). Early identification of and intervention for infants and toddlers who are at risk for autism spectrum disorder. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 34: 180–193.