When words trigger activity in the brain’s sensory and motor systems: It is not remembrance of things past

The observation of language-induced activity in the brain’s sensory and motor systems has recently revived the discussion of the potential contribution of these structures to language comprehension. This chapter briefly addresses some issues that underlie this embodied cognition hypothesis for language, namely associative learning.

IT IS NOT REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PAST

Over the last years, a large number of brain imaging studies provided evidence that written or spoken descriptions of motor actions activate regions of the brain that were typically associated with the planning and execution of motor actions (Aziz-Zadeh et al., 2006; Boulenger et al., 2009; Hauk et al., 2004; Kemmerer et al., 2008; Pulvermüller et al., 2001; Tettamanti et al., 2005). Words referring to face, arm, or leg actions, for instance, differentially activate areas along the motor strip that are adjacent to or overlapping with areas activated by a movement of the effectors involved in the described action (e.g., Hauk et al., 2004). Similar observations have also been made during processing of words describing visual attributes such as color (which activates an area near the color-responsive area V4; e.g., Chao and Martin, 1999; Martin et al. 1995), visual motion (which activates regions in the posterior-lateral-temporal cortex known to be involved in processing visual motion; e.g., Bedny et al., 2008), and so forth.

Given the arbitrary relationship between the phonological sounds of words and their meanings (but see sound-symbolism research: e.g., Imai et al., 2008, Kovic et al., 2010; Nygaard et al., 2009; Ramachandran and Hubbard, 2001), language-induced sensory or motor activity is necessarily the result of experience and learning. In fact, according to an idea first put forward by Pulvermüller (1999, 2005; see also Del et al., 2009; Keysers and Perret, 2004, for similar ideas), links between brain regions involved in language processing and brain regions involved in perception or action planning/execution could develop through Hebbian associative learning (see also Coello and Bartolo, this volume; Coello and Bidet-Ildei, this volume; Jacob, this volume; Rueschemeyer and Bekkering, this volume; Stieglitz Ham and Bartolo, this volume; Taylor and Zwaan, this volume). For instance, since “action words” (mostly verbs) are often acquired and experienced in the context of execution of the depicted actions (Goldfield, 2000), and given Hebb’s postulate that synchronous activity of neurons leads to the formation of neuronal assemblies (Hebb, 1949), Pulvermüller suggested that neural networks, including left hemisphere perisylvian language areas and motor areas, emerge with experience. By means of these shared circuits, perceiving an action word automatically triggers activity in motor regions of the brain. In keeping with this associative-learning account, Revill et al. (2008), who trained participants to associate novel verbal stimuli with motion changes of objects, demonstrated that once word-referent relations were acquired, participants showed language-induced activation in cortical regions that had been linked to the processing of visual motion (i.e., left MT/V5 and its anterior part). Similarly, Fargier et al. (in press), who studied the dynamic of novel word-action associations by analyzing motor-related brain activity (reflected by the desynchronization of EEG in the 8–12 Hz frequency range; “μ rhythms,” Gastaut, 1952), showed that desynchronization in the μ frequency band observed during viewing of action-depicting videos also became evident during listening to verbal stimuli that had been coupled with these actions.

Hence, like the rich associations triggered by the taste of the tea-soaked madeleine in Marcel Proust’s famous novel,1 language-induced sensory and motor activity emerges because of links that the brain establishes between words and their experiential referents. Yet, while few would claim that the associations triggered by Proust’s madeleine are anything else than involuntary childhood memories, the same does not hold for the interpretation of language-induced sensory and motor activity. For many researchers, the latter bears something about the word’s meaning (e.g., Allport, 1985; Barsalou, 2008; Boulenger et al., 2006; Gallese and Lakoff, 2005; Fischer and Zwaan, 2008; Pulvermüller, 1999, 2005). Why this difference?

ASSOCIATIVE LEARNING AND THE MEANING OF WORDS

Going back to Allport (1985), who proposed that the same neural elements involved in coding the sensory attributes of an object also make up the elements that represent object concepts in semantic memory, the majority of current theoretical positions sees conceptual knowledge as the result of the joint action of different brain regions that code for sensory, motor, and verbal information (e.g., Lambon Ralph et al., 2010; Patterson et al., 2007; Pulvermüller, 1999, 2005; Rogers et al. 2004). Within this theoretical frame-work, Mitchell et al. (2008), for instance, recently proposed a computational model that predicts fMRI activity associated with thinking about any of thousands of concrete nouns. The model is based on the assumption that the neural basis of the semantic representation of concrete nouns is related to the distributional properties of those words in a given language. Based on a large text corpus, the authors thus first identified how often a given concrete noun co-occurred with a set of 25 key words, corresponding to basic sensory and motor activity (e.g., see, hear, smell, eat, taste, enter, open, etc.). From these co-occurrence statistics (see Ji et al., 2008; Landauer and Dumais, 1997, for details for such statistical analyses), the authors then computed intermediate semantic features for the concrete nouns. For a word like celery, for instance, one such intermediate semantic feature is defined by the frequency with which celery co-occurs with the verb “eat”; another feature is defined by the frequency with which the word co-occurs with the verb “taste,” and so forth. The meaning of the word celery was then indexed as a vector of all intermediate semantic features. Based on brain-imaging data (fMRI), obtained while participants were processing the set of 25 key words and taking into account every voxel location in the brain, the model then successfully predicted the pattern of brain activity observed when participants processed the word celery (or any other concrete noun), by combining the fMRI signature associated with each of the 25 intermediate semantic features. However, while these results are impressive, the fact that various cognitive processes (including those triggered by Proust’s madeleine) arise from associative transformations implies that simply revealing underlying associative neural networks is not enough to account for how the brain computes word meaning. This point was also implicit in Mahon and Caramazza’s (2008) critique when they compared the embodied cognition hypothesis to Pavlovian conditioning:

Consider the Pavlovian dog, which salivates when it hears the bell. One may ask: How does all of the nervous system machinery that results in the conditioned response in the dog become “activated” by the bell? Does all of that activation constitute “recognizing the bell?”

(p. 65)

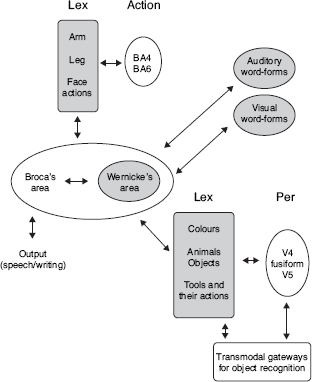

In an attempt to describe how diverse cognitive domains evolve from sensation, Mesulam (1998) proposed that all cognitive processes arise from analogous associative transformations. These transformations occur along a core synaptic hierarchy that includes primary sensory, unimodal, heteromodal, paralimbic, and limbic zones of the cortex. All these zones are highly interconnected and each cortical area provides a node for the convergence and divergence of afferents and efferents. The highest synaptic levels are housed in the heteromodal, paralimbic, and limbic zones, referred to as transmodal areas. These latter areas serve to bind information from unimodal and other transmodal areas into integrated multimodal representations. According to Mesulam, the resulting synaptic organization allows each sensory event to cause multiple cognitive and behavioral outcomes. Differences in the nature of the cognitive operations simply result from the anatomical and physiological properties of the transmodal nodes that act as gateway for the transformations. The hippocampal and entorhinal components of the limbic system, for instance, serve as transmodal nodes for memories of personal events (episodic memory such as Proust’s madeleine), while Wernicke’s (and Broca’s) area serves as a node for linking sensory (auditory or visual) word-forms to the sensory or motor associations that (might) encode their meanings. A slightly modified version of Mesulam’s proposal for language, in which we added a motor component (depicted in light grey) not present in the original, is given in Figure 16.1.

Figure 16.1 A highly simplified schematic representation of aspects of lexical retrieval and word comprehension according to Mesulam (1998). Arrows represent reciprocal neural connections. Lex = areas for encoding prelexical representations related to colors, tools and actions; Per = areas for encoding sensory and perceptual features related to color (V4), faces and objects (midfusiform area), and movement (V5). Elements in light grey (top left) represent corresponding regions in cortical motor areas. A grey ground marks the network that links word-forms and sensory-motor structures.

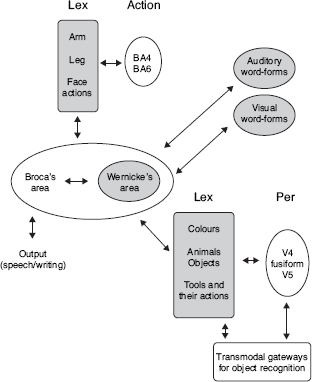

Figure 16.2 Various forms of learning and memory and their putative brain substrates (from Thompson, 2005).

Mesulam’s highly simplified proposal recalls an important issue, namely that different aspects and forms of associative learning and memory involve different brain systems. A schematic summary by Thompson (2005) of various forms of learning and memory and their putative brain substrates is given in Figure 16.2: Episodic memory and Pavlovian conditioning clearly involve distinct brain systems and neither compares to word-meaning associations. Yet, sensory and motor associations can be involved in many types of learning. Hence, if we seek to understand how sensory and motor processes relate to language (and conceptual thinking), reconsidering the broader neural language network might be beneficial because referring to associative learning alone is not sufficient.

MODAL OR AMODAL REPRESENTATIONS?

Another feature in Mesulam’s proposal that is worth stressing is that Wernicke’s (and Broca’s) area does not directly connect to areas that encode sensory and perceptual features related to color, objects, motion, etc., but to a region termed “Lex.” Without giving further details, Mesulam suggested that “Lex” corresponds to an “intermediary” lexical labeling area. This distinction was introduced because the pattern of neural activity for words depicting visual attributes, such as colors and motion, tends to be associated with activation of cortical areas that are nearby but do not (or only partially) overlap with regions associated with perception of the attributes (e.g., Bedny et al., 2008; Chao and Martin, 1999; Martin et al., 1995, 1996; Revill et al., 2008). The observed disparity, which has been clearly underlined for words describing visual attributes, also holds for words describing motor actions (e.g., Tremblay and Small, 2011; Willems et al., 2010), though in the motor domain it has been less explicitly mentioned. One possible interpretation of this finding is that “Lex” is a region that serves as “convergence zones” (Damasio, 1989) between structures that encode spoken/written word-forms and sensorimotor structures. According to Damasio (1989), convergence zones are local brain areas in association cortices that do not contain refined representations. Instead, these zones receive/send signals from/to different modalities, and enable correlated activity to occur in different regions of the brain. By way of these convergence zones—which evolve through learning—the brain can bind information represented in distinct regions into coherent events and can enact formulas for the reconstitution (remembering) of representations of events in sensory and motor cortices. Note, though, that in Mesulam’s model these convergence zones would be redundant with the function denoted to the transmodal node as represented by Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas.

Thompson-Schill et al. (2006), on the other hand, consider “Lex” rather as a potential reason to reject the embodied cognition view. With reference to Allport (1985), these authors argue:

there is a consistent trend for the retrieval of a given physical attribute to be associated with activation of cortical areas 2–3 cm anterior to regions associated with perception of the attribute. This pattern, which has been interpreted as coactivation of the “same areas” involved in sensorimotor processing, as Allport (1985) hypothesized, could alternatively be used as ground to reject the Allport model.

(p. 165)

According to Thompson-Schill et al. (2006), the observed “anterior shift” could, in fact, reflect an early step of a gradual process of transformation from modality specific toward amodal representations, stored somewhere else in the brain. As a consequence, sensory-motor reactivations, through which concepts might be comprehended, differ from those implicated in the acquisition of such concepts. Since “Lex” codes sensory and motor information at a more abstract level of representation, this region might provide a format that is particularly well suited to be associated with stimuli that have symbolic character.

Finally, the function that is supported by “Lex” could also arise as a consequence of associating sensory and motor information with word-forms. As a matter of fact, single-cell recordings in monkeys have shown that certain neurons in premotor cortex can represent fairly abstract descriptions of motor actions when these actions are associated with symbols. Nakayama et al. (2008) (see also Zach et al., 2008), for instance, trained monkeys to associate color cues with the command to reach and touch one of two simultaneously presented squares on a screen (e.g., when the cue is red or blue touch the left one of the two squares; when it is green or yellow touch the right one). Following training, in a large portion of the recorded premotor neurons, neural activity to the visual cues distinguished between left and right despite the fact that the pair of squares could appear at various locations relative to the monkey. That is, the actual movement triggered by a red cue could be to the left, the center, or to the right of the monkey, depending on where the two squares appeared on the screen in front of the monkey. Activity of these neurons thus signaled the selection of a forthcoming (abstract) action prior to the specification of the real motor plan (which was computed by a different set of premotor neurons, whose activity was conditional on the precise location of the target with respect to the monkey). Note, if “Lex” in the human brain codes comparable information, this would support the interesting idea that conceptual knowledge emerges as intermediary between sensory/motor knowledge and language (e.g., Coltheart et al., 1998).

THE PECULIAR CHARACTER OF WORDS

Unlike episodic memory or Pavlovian conditioning, another type of associative learning—i.e., multisensory perceptual learning—resembles greatly the Hebbian association learning that we discussed at the beginning of the chapter to account for language-induced sensory and motor activity. Research on multisensory perceptual learning investigates how partly redundant information from different sensory modalities is combined during perception (Shams and Seitz, 2008). For instance, when participants are asked to identify human voices, performance is better if, during the preceding training, voices are presented together with the speakers’ faces. In fact, during training, the coupling of voices and faces induces multisensory associations that subsequently facilitate unimodal voice perception: visual sensory cortices are recruited during auditory perception (von Kriegstein and Giraud, 2004). Hence, like action words, which by associations trigger activity in cortical motor structures, voices trigger activity in visual cortices. Evidently, the interpretation of multisensory associations is not the same as the one that is given to language–sensory/motor associations. Multisensory associations are seen as facilitators for the decoding of sparse and insufficient information from single modalities (von Kriegstein and Giraud, 2004). The crossmodal recruitment of visual sensory cortices during voice perception does not mean that visual faces are part of what voices are. One reason for the difference in interpretation in these two domains is that voices are not sign vehicles in the sense that words are.

Like the color cues in the study with monkeys described above, words are symbols because they stand for something other than themselves—yet, words are not proxy for their objects. The symbolic character of words results from the association of word-forms with the concepts they represent, not with the things themselves. While the traditional views of language underline the symbolic character of words, little is known about how words come to function as such. As the philosopher Susan Langer (1942) pointed out, one peculiar feature of words is that they have no value except as symbols: We perceive their meaning. The actual sounds are the vehicle by which meaning is expressed. Interestingly, the symbol function of words seems to outperform other types of sign vehicles.

As a matter of fact, infants as young as 3 months of age already treat words and tones differently vis-à-vis object categorization. In studies performed by Waxman and colleagues (Ferry et al., 2010; also Balaban and Waxman, 1997; Waxman and Markow, 1995), preverbal infants of different age groups were familiarized to various exemplars of a category (e.g., dinosaurs or fishes) accompanied by either a labeling phrase (e.g., “Look at the toma”) or a tone sequence (matched for basic physical characteristics to the phrase), both presented through a loudspeaker. Subsequent to the familiarization task, infants viewed novel category and new within-category exemplars. The results showed that infants who heard labeling phrases provided evidence of categorization, while infants who heard tone sequences did not. Hence, practically from birth, words exert an influence on human object categorization that is distinct from that of tones, despite the fact that tones could equally well serve as sign vehicle. Considering these aspects of the word-stimulus might thus also be critical for the understanding of how word meaning is established in the brain.

CONCLUSION

In this short chapter, we have pointed to some issues that might be worth investigating in order to advance our understanding of the role of language-induced sensory and motor activity in language processes. These issues range from the anatomical and physiological properties of involved brain substrates to the peculiar character of words as sign vehicle. However, the most crucial issue is probably the embedding of the observed phenomena within the broader context of research that aims at unveiling the mystery of human language.

NOTE

1 “And as soon as I had recognized the taste of the piece of madeleine soaked in her decoction of lime-blossom which my aunt used to give me (although I did not yet know and must long postpone the discovery of why this memory made me so happy) immediately the old grey house upon the street, where her room was, rose up like a stage set to attach itself to the little pavilion opening on to the garden …”. Marcel Proust (1913). Remembrance of Things Past. Volume 1: Swann’s Way: Within a Budding Grove (trans. C.K. Scott Moncrieff, 1922).

REFERENCES

Allport, D.A. (1985). Distributed memory, modular systems and dysphasia, in Newman, S.K. and Epstein, R. (eds), Current Perspectives in Dysphasia. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Aziz-Zadeh, L., Wilson, S.M., Rizzolatti, G., and Iacoboni, M. (2006). Congruent embodied representations for visually presented actions and linguistic phrases describing actions. Current Biology, 16: 1818–1823.

Balaban, M.T. and Waxman, S.R. (1997). Do words facilitate object categorization in 9-month-old infants? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 64 (1): 3–26.

Barsalou, L.W. (2008). Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59: 617–645.

Bedny, M., Caramazza, A., Grossman, E., Pascual-Leone, A., and Saxe, R. (2008). Concepts are more than percepts: the case of action verbs. Journal of Neuroscience, 28: 11347–11353.

Boulenger, V., Roy, A.C., Paulignan, Y., Deprez, V., Jeannerod, M., and Nazir, T.A. (2006). Cross-talk between language processing and overt motor behaviour in the first 200 msec of processing. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 18(10): 1607–1615.

Boulenger, V., Hauk, O., and Pulvermüller, F. (2009). Grasping ideas with the motor system: semantic somatotopy in idiom comprehension. Cerebral Cortex, 19: 1905–1914.

Chao, L. and Martin, A. (1999). Cortical regions associated with perceiving, naming, and knowing about colors. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 11(1): 25–35.

Coltheart, M., Inglis, L., Cupples, L., Michie, P., Bates, A., and Budd, B. (1998). A semantic subsystem of visual attributes. Neurocase, 4: 353–370.

Damasio, A.R. (1989). Time-locked multiregional retroactivation: a systems-level proposal for the neural substrates of recall and recognition. Cognition, 33(1–2): 25–62.

Del, G.M., Manera, V., and Keysers, C. (2009). Programmed to learn? The ontogeny of mirror neurons. Developmental Science, 12: 350–363.

Fargier, R., Paulignan, Y., Boulenger, V., Monaghan, P., Reboul, A., and Nazir, T.A. (in press). Learning to associate novel words with motor actions: language-induced motor activity following short training. Cortex.

Ferry, A.L., Hespos, S.J., and Waxman, S.R. (2010). Categorization in 3- and 4-month- old infants: an advantage of words over tones. Child Development, 81(2): 472–479.

Fischer, M.H. and Zwaan, R.A. (2008). Embodied language: a review of the role of the motor system in language comprehension. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 61: 825–850.

Gallese, V. and Lakoff, G. (2005). The brain’s concepts: the role of the sensory-motor system in reason and language. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 22: 455–479.

Gastaut, H. (1952). Electrocorticographic study of the reactivity of rolandic rhythm. Revue Neurologique (Paris), 87: 176–182.

Goldfield, B.A. (2000). Nouns before verbs in comprehension vs. production: the view from pragmatics. Journal of Child Language, 27: 501–520.

Hauk, O., Johnsrude, I., and Pulvermüller, F. (2004). Somatotopic representation of action words in human motor and premotor cortex. Neuron, 41: 301–307.

Hebb, D.O. (1949). The Organization of Behavior: A Neuropsychological Theory. New York: Wiley.

Imai, M., Kita, S., Nagumo, M., and Okada, H. (2008). Sound symbolism between a word and an action facilitates early verb learning. Cognition, 109: 54–65.

Ji, H., Lemaire, B., Choo, H., and Ploux, S. (2008). Testing the cognitive relevance of a geometric model on a word-association task: a comparison of humans, ACOM, and LSA. Behavior Research Methods, 40(4): 926–934.

Kemmerer, D., Castillo, J.G., Talavage, T., Patterson, S., and Wiley, C. (2008). Neuroanatomical distribution of five semantic components of verbs: evidence from fMRI. Brain and Language, 107: 16–43.

Keysers, C. and Perrett, D.I. (2004). Demystifying social cognition: a Hebbian perspective. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8: 501–507.

Kovic, V., Plunkett, K., and Westermann, G. (2010). The shape of words in the brain. Cognition, 114(1): 19–28.

Lambon Ralph, M.A., Sage, K., Jones, R.W., and Mayberry, E.J. (2010). Coherent concepts are computed in the anterior temporal lobes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 107: 2717–2722.

Landauer, T.K. and Dumais, S.T. (1997). A solution to Plato’s problem: the Latent Semantic Analysis theory of acquisition, induction and representation of knowledge. Psychological Review, 104 (2): 211–240.

Langer, S. (1942). Philosophy in a New Key: A Study in the Symbolism of Reason, Rite, and Art. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Mahon, B.Z. and Caramazza, A. (2008). A critical look at the embodied cognition hypothesis and a new proposal for grounding conceptual content. Journal de Physiologie, 102: 59–70.

Martin, A., Haxby, J.V., Lalonde, F.M., Wiggs, C.L., and Ungerleider, L.G. (1995). Discrete cortical regions associated with knowledge of color and knowledge of action. Science, 270: 102–105.

Martin, A., Wiggs, C.L., Ungerleider, L.G., and Haxby, J.V. (1996). Neural correlates of category-specific knowledge. Nature, 379: 649–52.

Mesulam, M.M. (1998). From sensation to cognition. Brain, 121: 1013–1052.

Mitchell, T.M., Shinkareva, S.V., Carlson, A., Chang, K.M., Malave, V.L., Mason, R.A., and Just, M.A. (2008). Predicting human brain activity associated with the meanings of nouns. Science, 320(5880): 1191–1195.

Nakayama, Y., Yamagata, T., Tanji, J., and Hoshi, E. (2008). Transformation of a virtual action plan into a motor plan in the premotor cortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 28: 10287–10297.

Nygaard, L.C., Cook, A.E., and Namy, L.L. (2009). Sound to meaning correspondences facilitate word learning. Cognition, 112: 181–186.

Patterson, K., Nestor, P.J., and Rogers, T.T. (2007). Where do you know what you know? The representation of semantic knowledge in the human brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 8: 976–998.

Pulvermüller, F. (1999). Words in the brain’s language. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22: 253–279.

Pulvermüller, F. (2005). Brain mechanisms linking language and action. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 6: 576–582.

Pulvermüller, F., Harle, M., and Hummel, F. (2001). Walking or talking? Behavioral and neurophysiological correlates of action verb processing. Brain and Language, 78: 143–168.

Ramachandran, V.S. and Hubbard, E.M. (2001). Synaesthesia: a window into perception, thought, and language. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 8: 3–34.

Revill, K.P., Aslin, R.N., Tanenhaus, M.K., and Bavelier, D. (2008). Neural correlates of partial lexical activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 105: 13111–13115.

Rogers, T.T., Lambon Ralph, M.A., Garrard, P., Bozeat, S., McClelland, JL., Hodges, J.R., and Patterson, K. (2004). Structure and deterioration of semantic. Psychological Review, 111(1): 205–235.

Shams, L. and Seitz, A.R. (2008). Benefits of multisensory learning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(11): 411–417.

Tettamanti, M., Buccino, G., Saccuman, M.C., Gallese, V., Danna, M., Scifo, P., Fazio, F., Rizzolatti, G., Cappa, S.F., and Perani, D. (2005). Listening to action-related sentences activates fronto-parietal motor circuits. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 17: 273–281.

Thompson, R.F. (2005). In search of memory traces. Annual Review of Psychology, 56: 1–23.

Thompson-Schill, S.L., Kan, I.P., and Oliver, R.T. (2006). Functional neuroimaging of semantic memory, in Cabeza, R. and Kingstone, A. (eds), Handbook of Functional Neuroimaging of Cognition (pp. 149–190). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Tremblay, P. and Small, S.L. (2011). From language comprehension to action understanding and back again. Cerebral Cortex, 21(5): 1166–1177.

von Kriegstein, K.V. and Giraud, A.L. (2004). Distinct functional substrates along the right superior temporal sulcus for the processing of voices. Neuroimage, 22(2): 948–955.

Waxman, S.R. and Markow, D.B. (1995). Words as invitations to form categories: evidence from 12-to 13-month-old infants. Cognitive Psychology, 29(3): 257–302.

Willems, R.M., Toni, I., Hagoort, P., and Casasanto, D. (2010). Neural dissociations between action verb understanding and motor imagery. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22: 2387–2400.

Zach, N., Inbar, D., Grinvald, Y., Bergman, H., and Vaadia, E. (2008). Emergence of novel representations in primary motor cortex and premotor neurons during associative learning. Journal of Neuroscience, 28: 9545–9556.