INTRODUCTION

When we face a perceived threat—anything that startles or scares us or is stressful or unexpected—our body’s reaction is to turn on the fight-or-flight response. This response, which erupts instantaneously in the oldest part of our brain, fires up the stress hormones, cortisol and adrenaline, and gets us ready to either run away from the perceived danger or, if we think we can overpower the threat, to stand our ground and fight. This response is not necessarily a bad thing. The two hormones are a helpful and life-saving part of our body’s response to stress and have saved our ass as a species for tens of thousands of years.

But it is important that the opposite reaction, the relaxation response, also be activated when the stress has passed so that the body’s functions can return to normal. This means we need to settle down and relax when the high-stress event is over. However, when the body’s stress response is activated so often that we don’t have a chance to relax, to come down and to return to normal, we end up in a state of chronic stress. Continuous stress, no matter what the source—be it reexperiencing a traumatic event, being deployed for the first time or continuously deployed, or our husband, wife, or boss yelling at us—takes its toll on our lives, our health, and our relationships.

Dr. Herbert Benson, the well-respected Harvard professor and author of The Relaxation Response, coined the term relaxation response over thirty years ago. He explained it as the polar opposite of the fight-or-flight response. One of the ways in which yoga works is by facilitating the activation of this response. Yoga practices give us things to do that bring our attention into the present moment through focusing on our breath, on our yoga posture, on a gazing point, or through the use of a variety of other yoga tools. In addition to the many physical benefits of a yoga practice that you might already be aware of, such as building strength, flexibility, balance, and agility, the corresponding mental effort to bring mindful attention to the present moment (in a safe and predictable environment like a yoga studio or gym or your living room) unites the body and mind. The effort to focus on the present moment steadies the mind, pulls it back into the body, and can create a calming and balancing response. This brings about many other physical and emotional benefits such as lower blood pressure, slower respiration and heart rate, and calmer, quieter mental activity that can directly contribute, over time, to improvement in overall quality of life—mental, emotional, and physical. That is surely something that can be a welcome aid to a returning veteran struggling to make sense of and adjust to a radically different environment than the one he or she just left. A regular yoga practice, whether meditation, breath work, or moving through postures, can help anyone in the military deal with the stress of facing deployment, being in the field itself, or transitioning back to civilian life.

Yoga develops awareness, and military training does the same. Almost all the military service men and women, both veterans and active duty, with whom I have worked, seem to be pretty conscious and aware of what is going on around them. That heightened awareness is perhaps what has helped you to survive, to be here now, reading this book. But that hypervigilance can turn into a liability rather than an essential tool for survival, and become a threat to your health and well-being.

In his book, Once a Warrior, Always a Warrior, Charles Hoge, a psychiatrist and retired US Army colonel, describes post-traumatic stress (PTS) as a paradox. Unlike “combat stress reaction”—which is an immediate reaction to severe stress on the battlefield, is not a mental disorder, rarely becomes PTS, and is treated immediately with rest and reassurance—PTS is defined by medical professionals as a specific set of symptoms that have gone on for at least a month. These symptoms fall into three categories: avoidance, reexperiencing, and hyperarousal. The irony is that every symptom is an essential survival skill in a war zone and that every one of them can also be a perfectly normal response to life-threatening events.

Everyone experiences trauma in life. Some people experience more catastrophic trauma than others. Not everyone who experiences trauma develops post-traumatic stress. In fact, relatively speaking, very few do. We don’t really know all the reasons that some people recover quickly while others struggle with lingering effects all their lives. Clearly there are many determining factors involved—genetics, upbringing, family history, personal health, and others. The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), categorizes post-traumatic stress as a trauma and stress-related disorder. But this diagnosis is changing. Post-traumatic stress is not an emotional or even a psychological disorder; it is a physiological condition that affects the functioning of every aspect of the body—the skeletal system, the cardiovascular and immune systems, inflammatory response, and hormone system balance. Yoga directly affects the physiological condition of all these various biomechanical and neurobiological systems, which is the main reason that the various yoga practices such as movement, breathing, and meditation can be so helpful. More and more, the preference for dropping the word disorder is finding its way into the medical lexicon, and many trauma specialists—both psychologists and psychiatrists—are in agreement that the condition is a normal response to an abnormal event, and not a psychological disorder. For this reason, I have chosen in this book to refer to post-traumatic stress (PTS), as simply that, and not as post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD.

Although warrior awareness can be an asset to help you see danger before others do and be more sensitive and compassionate to others’ suffering, the trick is to balance the ability to be aware and maintain the positive aspects of that sensitivity—without allowing that hypervigilance to run amok. Yoga can help. Although it isn’t a magic bullet and not intended as a substitute for therapy or as treatment for PTS or any specific disorder, it can help you to ramp the hypervigilance down. It is possible. And you, as a warrior, have great training for this work. You are a natural for yoga. The main difference I see between the discipline of being in the armed forces and the discipline of yoga is that the final objective in military training is to prepare the warrior for battle with an external force or enemy. In yoga training, the preparation is also geared toward battle, but the enemies are within!

If you are wondering how yoga can help you and your family restore a sense of normalcy to your lives after or during deployment, following are a few of the most frequently reported benefits received by the Give Back Yoga Foundation. This nonprofit, which I cofounded, supports yoga programs for military personnel all over the country and gathers feedback from veterans and active duty military members who are regularly practicing mind-body healing techniques like those found in the yoga practices of movement, meditation, and breathing exercises. The list of benefits is pretty amazing, and we continue to hear experiences like these every day:

• reduction of anxiety and depression

• better ability to regulate anger and hypervigilance

• improved concentration

• increased ability to relax

• increased focus on the positive rather than the negative

• greater mental clarity

• pain relief

• more oxygen in body to help repair wounds, burns, and physical injuries

• lower blood pressure

• improved sleep

• increased ability to deal with the mental and emotional strain of combat

• greater access to peace of mind

• support in addiction recovery

Some of the letters and emails we have received from our students and the students of our friends and colleagues tell us many warriors are recognizing the benefits of yoga in helping to manage and process their combat experience and “navigate life after war.”

I started yoga when I was in the Marines. It helped calm me down when I was feeling extremely anxious. When I got out, I really needed something to relieve my anxiety, anger, trauma, and depression. Eventually I got tired of feeling so negative about everything and so bad about myself. I had a bunch of injuries, and because I had trouble working out the way I once did, I had a lot of pent up energy in my mind and body. I [eventually] became a yoga teacher, and everything started to change. I learned to meditate, to breathe deeply, and to feel like I had some control of my mind when I felt lousy. Yoga saved my life.

CAPTAIN, US Marine Corps

When I first began yoga in 2001, the vast majority of military members were very doubtful about its benefits. Since then, more and more military personnel are accepting yoga. It is amazing how word spreads, and how much people like it. Military personnel don’t realize how much they need yoga until they try it.

US NAVY OFFICER, practicing in Iraq

I am an active duty soldier with over twenty-five years of service in the US Army. I have been jumping out of airplanes for about nineteen of those years. Last year, I went crashing through some trees on an airborne operation and hit the ground harder than normal. I was diagnosed with degenerative disc disease with arthritis. I’m currently deployed to Iraq and have incorporated yoga into my physical fitness regimen. My back feels great without the muscle relaxers and painkillers. Yoga has been the candy for my spine. I will be doing yoga well into my senior citizen years.

SERGEANT MAJOR, US Army

Whether you are just entering military service, preparing for deployment, or returning home after service, the transition from where you are to where you are going can be tough. The journey back home, for example, is a welcome thought but a challenging shift. You are not the same person you were when you deployed. You have changed, and life back home has changed. You have been trained in the skills of a warrior. These skills have served you well and can continue to serve you well. There is no reason to unlearn them. But some of these skills, which are essential to survival in a war zone, may be a bit over the top for a peaceful and relaxing life at home that is radically different from the place you just left. To be happy and to find your way as a warrior in a civilian environment, these skills might need to be adjusted slightly, ramped up or toned down, to adapt to your new home environment.

Yoga, like warrior training, also teaches skillful means. These means are developed through practice, much in the same way as military readiness is gained by a warrior, and in yoga that includes movement, breathing exercises, and meditation practices. These practices also build strength, courage, and awareness—again much like your military training. They help you to feel connected to the world in a positive way, give you firm ground to stand on, and show you ways to successfully navigate the tricky waters that lie between military life and home.

Whether or not you are ready for or even interested in taking a yoga class at a local studio, this book can be an alternative to attending public classes, or it can be preparation for taking a class at a studio. It can also, of course, be an adjunct to any class you may already be taking. However, no matter how experienced a teacher or yoga studio may be with trauma-sensitive yoga, there is always the possibility of many uncomfortable moments or “triggers” for you. How soon you may be ready to explore a class is up to you. It will be different for every person.

Depending on what studio or school of yoga you stumble into and what teacher you get, there can be physical contact between you and the teacher, the class may be very crowded, it may be hot or even overly hot, or instructions can be given in a very authoritarian or militaristic tone by some teachers. Be prepared.

The sequences presented in this book are pretty much my own invention, based on my personal experience both as a practitioner and as teacher working with veterans and military service personnel, so you probably won’t be able to find anyone who teaches this identical sequence, unless it is someone I trained. If it is helpful to you, you can find a listing of teachers who have been certified by me on my website, berylbenderbirch.com.

SPECIAL TIPS FOR WARRIORS WITH PHYSICAL LIMITATION OR DISABILITY

This book is for everyone, all warriors, regardless of limitation or disability. One of my students—a young, fit, and very tight veteran with one severely disabled arm—called recently to tell me about a modification he had figured out for an arm balancing posture called Crane Pose. I have always taught that all of the yoga practices—from movement to meditation—can be helpful to everyone because each posture and physical movement can be adapted. I asked this student for any tips he could offer warrior brothers and sisters who want to try yoga but might feel discouraged from attempting the physical practices due to physical limitation or disability. He said, “Just start where you are and do what you can. That’s what I did.”

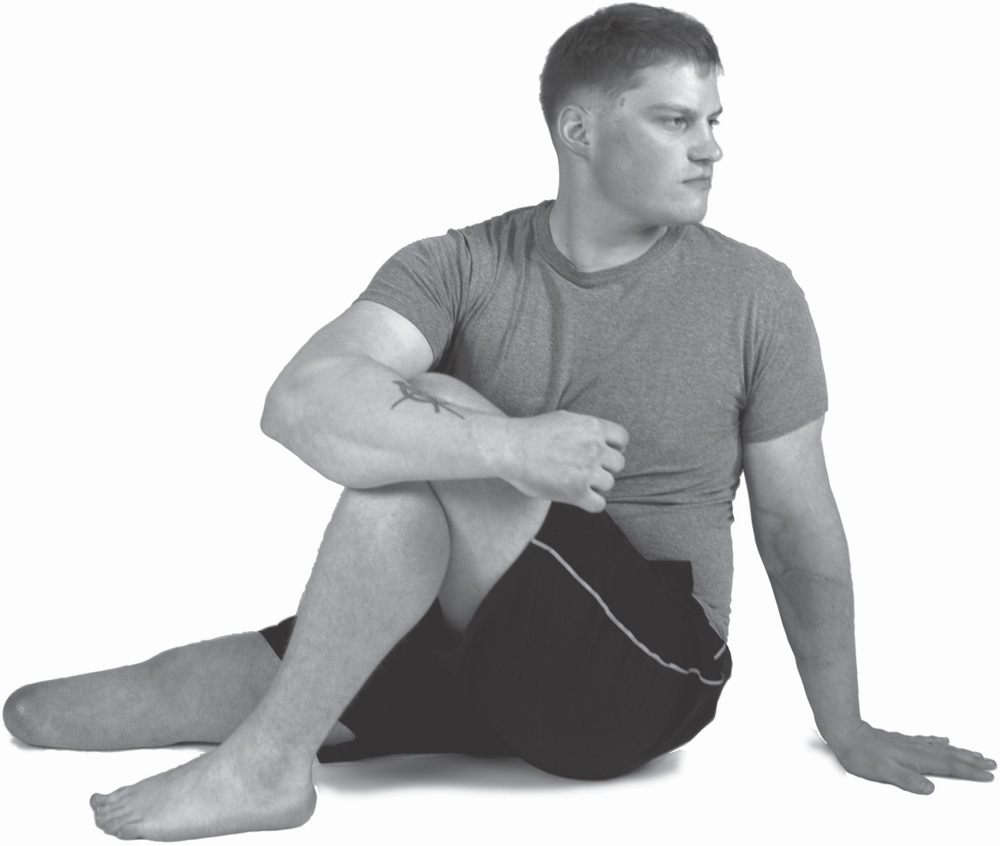

FIGURE I.1 Seated Twist Posture

Over the many years I have been teaching yoga, I have worked with a vast assortment of people with many different limitations, injuries, and disabilities. When designing a practice for an individual, with whatever limitation they might experience, I always go back to the basic practice as it is presented in this book and then I work from there. Along with my student, I look at a posture, and together we figure out how we can do this posture rather than why we can’t do it.

There is always something you can do. Ann Richardson Stevens has been teaching yoga in Virginia Beach military settings for many years. She specializes in adapting yoga for individual needs and works with a number of marines and navy SEALs, both in her studio and at various bases in the area. She shares my can-do approach. For example, one of her students cannot do standing postures because one of her legs was amputated. But the student can do the upper body part of the posture, so she does that.

Do what you can. If you can pick up this book and look through it, you can do this yoga stuff. Approach the book one page at a time. Work your way through it. If there is something that doesn’t work for you, for one reason or another, don’t just dismiss it. See if you can figure out a way to adapt or modify the posture or practice so that it does work. If you can’t do the standing postures, try a variation while seated. If you are lying on your back in a hospital bed and can’t move much, then just do the breathing practices. Because the most fundamental and important aspect of nearly every yoga practice is the breath. It is the “secret” key to how yoga works.

Breathing with awareness helps to regulate the nervous system, balance the energetic fields, and heal the body and mind. Plus, everyone can breathe. So breathe. Consciously. Learn the ujjayi breathing technique in chapter 2 and use it in the morning, at night, in the car, at work, or whenever you need physical or emotional balancing. As you approach each posture or breathing exercise or meditation practice, think about the benefits this particular practice might bring you. Then do a little. Do a little more. Be patient. Get a friend to do it with you. It will help. It will change you. You will feel better. And pretty soon, you will find yourself wanting to share these practices with others and become a conqueror who vanquishes enemies—not the enemies “over there,” but the enemies within.

If you need help personalizing your practice through modifications, turn to the International Association of Yoga Therapists to find someone local. Or you could find an experienced yoga teacher familiar with teaching yoga movement to persons with physical disabilities by emailing the Give Back Yoga Foundation.

INTRODUCING THE WARRIORS PHOTOGRAPHED IN THIS BOOK

Shane Billings, Sergeant, US Marine Corps. Shane lives in Pennsylvania and is pursuing an undergraduate degree at Penn State University.

Timothy Cole, Specialist, US Army. Tim lives in Crescent City, California, and is attending online college for an associate degree in renewable energy.

Elizabeth Corwin, Lieutenant, US Navy. Liz is a former F/A-18 pilot who lives in Stuttgart, Germany, and can be found upside down on her yoga mat or traveling teaching yoga workshops.

Philip Duguay, Lance Corporal, US Marine Corps. Phil lives in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. He manages a local hardware store, loves to garden, and grows his own food.

Alex Hampton, Lieutenant Commander, US Navy. Alex is currently a F/A-18 pilot and lives in Virginia Beach, Virginia, with his wife and three kids. He has accumulated over 2,500 flying hours and over 400 arrested landings with multiple deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan.

John R. Morgan Jr., Specialist 4, US Army, and Sergeant, Connecticut National Guard. John lives in Griswold, Connecticut. He owns a petroleum contracting company and enjoys farming and pottery.

FIGURE I.2 Thanks to Our Warrior Yoga Models. From left: Mike, John, Phil, Tim, Melinda.

Melinda Morgan, Lieutenant Colonel, US Air Force. Melinda lives in Virginia and is a public affairs officer with multiple deployments, most recently to Afghanistan for one year. She loves to paint and cook.

Michael A. Riley, Sergeant, US Air Force. Mike, a self-employed courier, lives in Bloomfield, Connecticut. He finds peace of mind through his yoga practice and now teaches yoga.

FIGURE I.3 Thanks to Our Warrior Yoga Models. From left: Shane, Alex, and Liz.