“I am sorry for such a long letter. I didn’t have time to write a short one.”

- Mark Twain

Best-selling author and marketing expert Seth Godin estimates that the average American is barraged with 1 million marketing messages each year.

That’s about 3,000 per day.

But that figure only includes marketing messages, not messages delivered by media spokespersons in news stories.

So let’s call it 3,100 per day.

Now consider the average American. He or she holds down a full-time job, looks after two children, tries to maintain a few social obligations, and suffers from a chronic lack of sleep. That over-scheduled person has almost no time for messages about anything to seep in.

Despite that challenge, successful spokespersons regularly manage to cut through the clutter and deliver a message that reaches—and resonates with—those exhausted people. This section of the book will help you craft messages that allow you to do exactly that.

A message is a one-sentence statement that incorporates two things: one of your most important points and one of your audience’s most important needs or values.

Messages often include a call to action, in which the audience is asked to do something specific, such as sign a petition, visit a website, or buy a product.

Aim for three main messages. Three is widely regarded as the right balance between too few (leading to audience boredom) and too many (leading to low audience retention).

This book focuses on messaging for general audiences, but you can also develop more tailored messages for specific audiences (such as potential donors, prospective customers, a crucial voting bloc) using the same technique you’ll learn in the next several lessons. Although your messages for each individual audience may differ from the ones you create for your general audience, they should all reflect similar values and themes.

You will probably not use your messages verbatim in media interviews very often; rather, you will communicate the themes of your messages in your own words. But since messaging forms the foundation of everything you communicate—in the media, during public presentations, on your website, in brochures, and even during casual conversations—it is important to invest time in developing powerful messages up front.

Messages are not the same as slogans; they are fully formed one-sentence ideas:

“By investing in infrastructure today, we will create hundreds of thousands of jobs, resuscitate the manufacturing sector, and build world-class highways that last for generations.”

In contrast, slogans are bumper-sticker or advertising phrases that contain only a few words:

“Rebuilding America, One Brick at a Time”

You will find several more sample messages in lesson 15.

All effective messaging should contain five critical elements, which are summed up by the acronym CUBE A. The next five lessons will discuss the components of CUBE A: Consistent, Unburdened, Brief, Ear-Worthy, and Audience Focused.

Finish these famous advertising jingles:

“Like a good neighbor, _____ _____ is there.”

“GE: We bring good things ____ _____.”

“The best part of wakin’ up is _______ in your cup.”

Did you find yourself singing along? If so, you’ve just experienced the first part of CUBE A, which requires that all messages be consistent.

You remember those commercials because the advertisers—State Farm, General Electric, and Folgers—stuck with their catchy ads long enough for them to become almost universally known.

Like memorable commercials, good messages require consistency and repetition. Spokespersons who change their messages from interview to interview prevent their audiences from understanding, remembering, and acting upon their messages, which usually require numerous exposures to become effective.

Just how many times do you have to repeat your messages in order to achieve your goals? Advertisers rely on the concept of effective frequency to determine the number of times they should run an advertisement. Commercials for simple products with high name recognition might need to be seen only twice to result in a sales increase, whereas ads for less familiar brands might need to be seen nine times.

In the age of media and message oversaturation, those numbers strike me as low. I advise my clients that moving their audiences from unawareness to action requires anywhere from 7 to 15 exposures—and sometimes more.

Consistency is broader than just media interviews—you should apply it across all of your communications platforms. Your website, public speeches, newsletters, annual reports, and all other internal and external communications should reflect the same themes as your media messages.

Think about it this way: every time a member of your audience hears a consistent message from you, your clicker goes up one notch on your march to 7 to 15 exposures. If I read your on-message quote in a newspaper article, you’re at one. If I visit your website and see it again, you’re at two. If I see your on-message interview on the local television news, you’re at three. But if your message is slightly different each time you communicate, you will never move the clicker past one.

Repeating your main messages may sound confining, but it’s not. In a few lessons, you will learn how to keep your messages fresh by reinforcing them with new stories and the latest statistics.

From The Audacity to Win by David Plouffe, Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign manager:

“We live in a busy and fractured world in which people are bombarded with pleas for their attention. Given this, you have to try extra hard to reach them. You need to be everywhere. And for people you reach multiple times through different mediums, you need to make sure your message is consistent, so for instance, they don’t see a TV ad on tax cuts, hear a radio ad on health care, and click on an Internet ad about energy all on the same day. Messaging needs to be aligned at every level: between offline and on-, principal and volunteer, phone and e-mail.”

Answers: State Farm; “to life”; Folgers

Memory studies consistently find that people forget the vast majority of what they read, hear, or see, especially if they are only exposed to the information one time.

One early study by Herman Ebbinghaus, the 19th-century German psychologist who was among the first to study human memory, found that people forget most of what they learn within days. Although his pioneering research was conducted more than a century ago, it still rings true for those of us who can never quite remember where we left our car keys.

The “U” in CUBE A demands that your messages remain unburdened by three things: wordiness, jargon, and abstractions. The more a message tries to say—and the more abstractly it tries to say it—the less likely it is to be memorable.

As a general guide, aim for messages that:

Too many words: Resist the temptation to jam everything you can into a single message—omitting less important details makes good sense. After all, if editors are only going to include two of your quotes in a finished news story, don’t you want them to choose your two most important messages? If the editor decides to run your fourth and seventh most important messages instead, I’d question whether your interview was a success.

Technical jargon: Unburdened messages require you to throw jargon overboard. Our clients in technical fields—such as scientists, physicians, and engineers—are the worst offenders of this rule. In fairness, their professional lives are spent awash in technical gobbledygook, their office conversations littered with words rarely used and barely understood by the general public. But considering that the public suffers from information overload, any words that prevent people from quickly grasping your meaning will result in messages that are quickly forgotten.

Even if you think your audience will understand more complicated terms as long as you use them “in context,” don’t use them (or at least define them if you do). They won’t hear the end of your sentence if they’re still trying to process the unfamiliar word you uttered at the beginning.

As an example, here’s an actual quote from a real press release:

“The gradualness (oriented primarily towards actual users) of the new Handy Backup is the succession of interfaces. With all the maximal simplicity and refined usability, the new one is designed to look structurally associative to the previous version…”

Abstractions: Abstractions, or broad concepts or ideas, are difficult for people to visualize. “Justice,” for example, is an abstraction—just try instantly conjuring up a detailed image of that word. A more concrete message about justice might mention the need to punish thieves who rob old ladies by imprisoning them for the next 20 years. That type of concrete message is much more memorable, and therefore works better for media messaging than an abstract one does. Chip and Dan Heath, the authors of the excellent book Made to Stick, write that “trying to teach an abstract principle without concrete foundations is like trying to start a house by building a roof in the air.”

The goal of most communications is to move an audience from lack of awareness to awareness to action. The more unburdened your messages, the more likely you are to achieve that goal.

During our message development workshops, we help our clients develop three one-sentence messages.

Invariably, someone asks if they can add a second sentence to one of their messages. The person asks the question in the belief that their work is more complicated than that of most other groups, therefore requiring a more detailed explanation.

My answer is always the same: “No.”

Writers of newspaper headlines can summarize the world’s most consequential topics (domestic terrorism, international warfare, global health pandemics) in just a few words. If they can effectively communicate such complex matters using nothing more than a short phrase, surely our clients can articulate a main message in a single sentence.

The “B” in CUBE A, therefore, demands that your messages remain brief.

How brief? One study from Harvard’s Center for Media and Public Affairs found that the average quote airing on evening newscasts lasts just 7.3 seconds. Since most of us speak an average of two or three words per second, that translates to a measly 18 words per quote. I’ll cut you a little slack. Aim for no more than 30 words in each of your three messages.

Although the Harvard study focused on television news, the same need for brevity exists for the print media. Next time you read a newspaper, count the number of words in each quote. You’ll probably find that each quote runs somewhere between 8 and 20 words.

Before you dismiss the news media as shallow for running such short blurbs, consider their rationale. Excluding commercials, a half-hour television news broadcast lasts just 22 minutes. Minus sports and weather, the program might have 14 minutes left for news. That allows time for just seven two-minute stories, most of which require a set-up, a close, and an opposition voice. No wonder they only have 7.3 seconds for your quote!

Most people find it frustrating to reduce their three main messages to just three sentences. Don’t despair. Frustration is an important part of the process, and your disciplined self-editing will result in stronger, more effective messages that stand a greater chance of breaking through and reaching your audience.

I learned that lesson as a young staffer at ABC’s Nightline With Ted Koppel. After completing my first 16-paragraph feature for the Nightline website, my senior producer told me to cut it in half. When I presented him with the eight-paragraph version, he told me it was better—and to cut it in half again. I hated him for making me go through that exercise, but he was right. Four paragraphs were better than eight; eight were better than sixteen. That same lesson holds true for your messages.

Case Study: “Death” Tax vs. “Estate” Tax

Can you communicate something of meaning in just one sentence? Yes, and pollster Frank Luntz goes even further, suggesting you can be effective with one word.

In his book Words That Work, Mr. Luntz describes his work to help Republicans eliminate the estate tax, which taxed people who inherited a windfall from a wealthy relative.

He found that while Americans didn’t support the abolition of an “estate” tax, which evoked images of sprawling landscapes and mega-mansions, they did support the elimination of the “death” tax, which struck many Americans as inherently unfair. Proponents of its repeal adopted the phrase “death tax” and won the debate.

Before I trained the top spokespersons of one government agency, their public affairs team drafted a few messages for them. The messages were full of seemingly endless sentences that read well enough on paper (sort of), but were almost impossible to speak aloud during media interviews.

I changed this example slightly to protect the client’s confidentiality, but the complexity of the message remains intact:

“This multilateral agreement, and its steady progress forward, is critical because it will protect Americans who could otherwise be maimed or killed should they consume—knowingly or unknowingly—unapproved imported meats, unpasteurized dairy products, or dangerous unregulated alcoholic beverages.”

Now that you’ve read that message, go back and speak it aloud.

Since you probably don’t speak that formally in everyday conversation, you shouldn’t during media interviews, either. (If you still do so by the time you finish The Media Training Bible, you might get more value from the book by using it as a doorstop!)

The “E” in CUBE A is for “ear-worthy.” The above message fails because it was written for the eye, not the ear.

Below is an alternate version of that message; try speaking this one aloud:

“We need to sign this agreement quickly to protect Americans from dangerous meats, dairy products, and alcoholic beverages.”

The above sentence is written for the ear, and most speakers can deliver it in a much more natural manner.

Here are five tips to help you write for the ear:

Follow the lead of the great American writer Mark Twain, who once quipped, “I never write ‘metropolis’ for seven cents, because I can get the same price for ‘city.’ I never write ‘policeman,’ because I can get the same money for ‘cop.’”

According to Oxford Online, the most popular pronoun in the English language is “I.” That means if I listen to your message, I’ll need to know how I will be affected to determine whether I should act or if I even care.

So you may have noticed a small problem after reading the first four parts of CUBE A: They’re all about you, not your audience.

The “A” in CUBE A helps ensure that your message is “audience focused.” Effective media messages must incorporate your audience’s needs and values; those that do will resonate much more deeply.

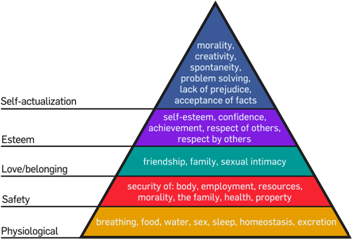

Needs refer to things people require or desire. In the 1940s, psychologist Abraham Maslow identified the most common human requirements in his “Hierarchy of Needs.” Human needs, he said, include safety and security, family and friendship, health, confidence, respect by others, and love. In today’s fast-moving world, I would add time, work-life balance, and convenience to his list.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Values refer to the guiding principles people and communities share, including patriotism, compassion or aggression, and self-reliance or collaboration.

Most values are subjective. For example, churchgoers believe in a higher power while atheists lack religious faith. Yet they both share the conviction that their values are correct. Those types of disagreements about which values are “right” drive political and social argument, something you see on display in debates and television commercials every four years during presidential campaign season.

For media messaging, the perfect marriage exists somewhere between your goals and your audience’s needs and values.

Case Study: IBM Press Release

I expected the worst when I came across a press release with this headline: “Southeast Texas Medical Associates Building Strong Post Treatment Care Programs with IBM Business Analytics Software.”

To my surprise, the release wasn’t a self-indulgent and product-focused pitch, but rather an audience-focused announcement framed within the needs of patients:

“Each day we challenge ourselves to respond faster, more efficiently and more effectively to the needs of our patients. You’d be surprised at the demand we get from our patients; they expect us to not just treat their ailments today, but to help them put plans in place to tackle ailments and challenges they will eventually face when dealing with a chronic disease like diabetes,” said Dr. James Holly, CEO, Southeast Texas Medical Associates.

This message succeeds because it isn’t about IBM’s software, but instead what that software can do for you.

There are many different types of media messages, but they frequently fit within one of the following four categories:

In the messages below, you’ll notice overlap among the categories. That’s because the same message can usually be written many different ways, depending on your goals.

1. The Fact/Result Message

This message spells out the link between a fact and its implication.

“Pennsylvania’s unreasonable malpractice laws have resulted in thousands of pregnant women living more than 100 miles from their obstetricians, a potentially life-threatening distance during medical emergencies.”

“Children in low-income communities receive a much poorer education than children from wealthier areas, and are too often doomed to a lifetime of low-paying jobs as a result.”

2. The Problem/Solution Message

This type of message describes the problem in the first clause and its solution in the second; that formula can also be reversed.

“Sterling Lake has become badly polluted and is no longer safe for swimming or fishing, but by closing it for three years, we can restore it and open it for swimming and fishing again.”

By loosening Pennsylvania’s unreasonable malpractice laws, thousands of pregnant women will be able to find a local obstetrician who can help in case of a medical emergency.”

3. The Advocacy or Call-to-Action Message

This kind of message goes a step further than the previous ones, providing your audience with a specific call to action.

“Call your state senators and tell them to pass this bill so that pregnant women no longer have to drive 100 miles to visit their obstetrician.”

“More American workers are living in dire poverty than at any other time since the early 1900s, so I’d ask everyone listening to sign our petition to Congress demanding a fair minimum wage at (Insert Website Address Here).”

4. The Benefits Message

Benefits messages focus on selling points for potential buyers.

“We are taking the hassles out of air travel by offering passengers the airline they’ve long wanted, with free itinerary changes, more legroom, and Internet access.”

“Using our print-on-demand service, our customers can upload their work on Thursday and have it bound and delivered on Friday—for half the price of traditional printers.”

When you begin crafting your three messages in the next lesson, mix and match these message types. For example, a nonprofit organization might use two problem/solution messages along with a call-to-action one, while a small business might use a fact/result message, a problem/solution message, and a benefits message. If you’re stuck, create four versions of each message to determine which one helps you accomplish your goals best.

This lesson will focus on crafting three winning messages about your company or organization for the general public. You can also use the same technique to develop more specific messages for individual topics or campaigns, or for different audiences.

If you create messages for individual topics or campaigns, remember that those messages should also reinforce your overall organizational messages.

For example, a women’s health nonprofit might have three overall messages: one that emphasizes treatment, another that focuses on prevention, and a third about research. The group may also have numerous specialty areas, such as neonatal health, breast cancer, and bone loss. The messages about a specific specialty area, say breast cancer, should help reinforce the overall messages about the importance of treatment, prevention, and/or research.

Step One: What You Want

What are the most important things the public needs to know about your organization’s work? Begin typing some ideas. Don’t be self-critical—just brainstorm and type anything (a word, a phrase, a sentence) that comes to mind. When you’ve run out of gas, save and close the document. Come back a few days later with fresh eyes and add anything you might have missed.

When you’re satisfied that you’ve fully completed your brainstorming, select the three thoughts that represent what you most want the public to know about your organization’s work. Write them out in sentence form as three separate messages, similar to the examples provided in the previous lesson. Don’t be discouraged if you aren’t creating perfect messages immediately—you’re aiming for a starting point, not perfection.

Step Two: What They Need

Put your messages aside for a while. Open a fresh document and brainstorm everything you can about what the general public wants or needs from you.

Let’s say you were part of the group trying to help pregnant women in Pennsylvania. While brainstorming what the general public wants related to that issue, you might have said:

When you finish brainstorming, select the three items you think your audience wants or needs from you most. Then, pull out your messages. Are those three needs represented in your messages? If so, you’re finished. If not, edit your messages to articulate them within the context of what your audience needs.

As an example, consider this message:

“By loosening Pennsylvania’s unreasonable malpractice laws, thousands of pregnant women will be able to find a local obstetrician who can help in case of a medical emergency.”

That message reflects the first two audience needs listed above: to protect the health of mother and child, and to ensure easy access to obstetricians.

Step Three: Begin Your Message Worksheets

Once you’ve completed your three messages, turn to lesson 93. Recreate the worksheets on a piece of paper or on your computer, and write your messages down, one on each of the three message worksheets.

Congratulations! You’ve now created three terrific messages, a significant achievement. Of course, if you simply repeat those three sentences over and over during your next media interview, you’ll infuriate the audience and alienate the reporter.

You can easily avoid that fate by using “message supports” to reinforce your messages. There are three types of message supports: stories, statistics, and sound bites. For each of your messages, you should develop at least two of each type of support, which will allow you to articulate the main themes of your messages in every answer without ever sounding repetitive.

The Message-Support Stool

Message supports can be paired with a message or used on their own. For example, you might answer one question using a message, the next using a message paired with a story, and another using only a statistic.

The key is to make sure that all of your statistics, stories, and sound bites reinforce your messages.

The first two legs of the stool are stories and statistics. When speaking to general audiences, it is important to maintain an equal balance of both—stories will resonate better for some people, while statistics will be more effective for others. As author Frank Luntz notes in his book Words That Work:

“Women generally respond to stories, anecdotes, and metaphors, while men are more fact-oriented and statistical. Men appreciate a colder, more scientific, almost mathematical approach; women’s sensibilities tend to be more personal, human, and literary.”

Although social science indeed suggests that gender helps determine whether a person is more likely to prefer stories or statistics, my personal experience is that a person’s profession is a much more accurate indicator. For example, scientists tend to be “statistics” people regardless of gender, while social workers usually lean toward the “stories” side. Therefore, make sure you balance your interviews. If you tend to be a “stories” person, add an extra statistic or two; if you’re a “statistics” person, do the opposite.

The third leg of the stool is for “sound bites,” those short quips most people wish they could think up on the fly. The good news is that most great spokespersons plan their sound bites well in advance—they just deliver them as if they were improvised.

The following five lessons will teach you how to dazzle your audiences by using message supports in your next interview.

According to Howard Gardner, a professor at Harvard University, “Stories are the single most powerful weapon in a leader’s rhetorical arsenal.” Yet most people struggle to think of compelling stories that reinforce their messages.

That’s usually because they’re trying to think of a “big” story. In order to help people get unstuck, I tell them to think smaller. I encourage them to think of a single customer whose life was improved because of their product or a community that is enjoying the benefits of a new public school.

A story can be many things: your personal experience with a person, place, thing, or topic; somebody else’s experience; case studies in the news; or a historical or fictional example.

Take this message from a few lessons ago:

“By investing in infrastructure today, we will create hundreds of thousands of jobs, resuscitate the manufacturing sector, and build world-class highways that last for generations.”

A “story” to go with that message might say:

“The owner of one steel factory in Pennsylvania told me that his company is on the verge of bankruptcy, but that this bill would keep his factory open and his 200 workers employed. Plus, he said it would be nice to finally be able to build roads that don’t fall apart after every snowstorm!”

The message itself likely didn’t help you create a clear mental picture, but the story probably conjured up images of a factory floor, steelworkers, or potholed roads. Good stories do exactly that: they bring abstract messages to life through more tangible examples.

In Made to Stick, authors Chip and Dan Heath identified three types of “story plots” that are most commonly used to energize and inspire others. If you’re having a difficult time thinking of stories, these plots may help you brainstorm:

Case Study: Hurricane Mitch Strikes Honduras

When Hurricane Mitch hit Honduras in 1998, thousands of people died and hundreds of thousands were left homeless.

By the time ABC News anchor Ted Koppel made it to the Honduran capital, the magnitude of the hurricane had already been widely reported. He knew a show highlighting the number of deaths wouldn’t add much to the story.

While walking around the city, he came across a man holding a shovel in a debris field. Koppel asked what he was digging. “My house used to be here, and it was destroyed,” the man said. “But I built the front door of my house with my own hands, and damn it, I want it back.”

That poignant moment became the centerpiece of a program called “The Door.” The show focused on that man – who he was, what had happened to him, and what he was planning to do next. By telling that small story well, the audience was able to extrapolate and understand the much larger disaster.

Four and a half million Americans have Alzheimer’s disease.

Did that number make you think, “Wow!” Did it evoke a specific image of what 4.5 million people looks like? I’m guessing not.

The problem is that most of us can’t remember raw numbers or place them into a larger perspective. Yes, the second leg of the message support stool is statistics, but that isn’t the same as raw data. Your job is to take boring, impersonal numbers and provide them with meaningful context that elicits a powerful reaction.

For example, imagine you’re giving an interview to a Boston radio station. You might cite the Alzheimer’s statistic this way:

“Fenway Park seats 37,000 people. It would take 122 Fenway Parks to hold every American with Alzheimer’s disease. That’s four and a half million people in total who are afflicted with this awful disease.”

For most people that statistic, loaded with context, is more powerful. It paints a memorable mental picture and produces a “wow” response. Here are four additional ways to cite statistics:

“One in three adults living in Washington, DC, is functionally illiterate. Next time you’re on the Metro, look around you. Odds are that the person to your left or right can’t read a newspaper.”

Case Study: Christian Children’s Fund Commercials (V)

If you’re of a certain age, you probably remember those old television commercials for the Christian Children’s Fund. In them, actress Sally Struthers (All in the Family) sold viewers the promise of saving a child for “the price of a cup of coffee.”

A quarter-century later, those ads are still memorable. And the way Ms. Struthers used numbers in those commercials is a big reason why.

The ads succeeded by reducing numbers down to a manageable price tag for most viewers: “For about 70 cents, you can buy a can of soda.…In Ethiopia, for just 70 cents a day, you can feed a child like Jamal nourishing meals.”

Imagine if Ms. Struthers had used an annual price tag instead of a daily one by saying, “You can save a child for just $255 a year.” Few people would have anted up, and the ads wouldn’t be remembered today.

Have you ever noticed that certain media guests seem to have the knack for always coming up with the perfect quip?

It’s true that some of those people possess a rare gift for ad-libbing. But for the rest of us, Mark Twain captured it best when he said, “It usually takes about three weeks to prepare a good impromptu speech.”

A sound bite is a short phrase or sentence that expresses one of your messages in a particularly memorable or witty manner (they are occasionally slightly longer). The media love sound bites and audiences remember them. They make dull stories livelier and boring guests more interesting.

Below are 10 examples of media-friendly sound bites. In the next lesson, you’ll learn how to create memorable sound bites that will hook the media and the public.

”It’s like trying to fill the bathtub with the drain open.” – Mary Johnson, Medicare policy analyst

“Any one flight in space on the space shuttle is as dangerous as 60 combat missions during wartime.” – John Young, astronaut

“We’re burning the furniture to heat the house.”— John H. Quigley, Pennsylvania Department of Conservation, on hydraulic fracturing

“She couldn’t get elected if two of her opponents died.” – Peck Young, political consultant

“Not only is the president’s honeymoon over, he now has a divorce on his hands.” – Marshall Wittman, pundit

“With all the money we owe China, I think we might rightly say, ’Hu’s your daddy.’” – Rep. Michele Bachmann (R-MN), referring to Chinese president Hu Jintao

“I outwit them and then I out hit them.” – Muhammad Ali, three-time heavyweight boxing champion

“Our choices right now are not between good and better; they’re between bad and worse.” – Alan Greenspan, former chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve

“My favorite recent movie is Hereafter. I didn’t cry at the end—but I thought about it.” – Michael Jordan, former NBA star

“How many times are we going to gamble with lives, economies, and ecosystems?” – John Hocevar, Greenpeace USA

Case Studies: History’s “Impromptu” Sound Bites (V)

Two of the late 20th century’s most memorable sound bites were planned well in advance:

O.J. Simpson Trial, 1995: At the O.J. Simpson murder trial, attorney Johnnie Cochran instructed the jury, “If [the glove] doesn’t fit, you must acquit.” Cochran’s line wasn’t improvised; it wasn’t even his. Another member of Simpson’s legal team, Gerald Uelmen, created the sound bite. Either way, that quip was the key to Simpson’s acquittal.

Vice-Presidential Debate, 1988: When young Republican VP nominee Dan Quayle defended his preparedness for office by saying he had the same amount of experience as John F. Kennedy, his opponent pounced. “I knew Jack Kennedy,” said Democratic VP nominee Lloyd Bentsen. “Jack Kennedy was a friend of mine. Senator, you’re no Jack Kennedy.” The crowd cheered enthusiastically at his “improvised” line. But the line wasn’t improvised. A clever political consultant created it in advance.

Few people can compose captivating sound bites in a single sitting. Don’t give up. You can develop media-friendly sound bites.

Great sound bites are all around you. Listen closely during conversations with friends and colleagues. What are intended as throwaway comments during casual banter often contain a gem worth saving—so keep pen and paper nearby to record the unexpected gold.

Marcia Yudkin, the “Head Stork” of Named At Last, a naming and tagline development company, came up with 17 tips to help spokespersons create memorable sound bites. I highly recommend her ebook The Sound Bite Workbook. Among other ideas, she advises spokespersons to brainstorm a list of keywords related to their topic area, look in a thesaurus for unexpected word options, and identify relevant homophones.

Below, you’ll find 10 types of sound bites the media regularly quote, along with examples for each. (Thanks to Marcia for her help with this list.)

Exercise: Complete Your Message Worksheets

Take out your message worksheets (see lesson 93), on which you should have already written or typed your three main messages. Brainstorm at least two stories, statistics, and sound bites that reinforce each of your three messages, and add them to your worksheets.

This lesson will illustrate how the individual pieces you’ve created—your messages and message supports (stories, statistics, and sound bites)—fit together.

You may remember this message, about the risks pregnant women in Pennsylvania face, from lesson 15:

“By loosening Pennsylvania’s unreasonable malpractice laws, thousands of pregnant women will be able to find a local obstetrician who can help in case of a medical emergency.”

A story that would fit beneath that message might say:

“Jane Jackson, a 26-year-old from Altoona, was in her seventh month of pregnancy last year when she went into labor. She was by herself and called 9-1-1. The paramedics got there in time but didn’t have the skills to help when her baby was unable to breathe. Her baby son died. If her skilled obstetrician lived closer, he likely would have been able to save her baby.”

A statistic under that message might be:

“More than 18,000 women of childbearing age in Pennsylvania live at least 100 miles from the closest obstetrician.”

A sound bite supporting that message might read:

“Having your doctor 100 miles away is kind of like keeping your Band-Aids at a friend’s house—they’re useless when you need them most.”

The following sample interview shows you how to embed your messages and message supports seamlessly into every answer.

SAMPLE INTERVIEW

Question 1: Why is there a shortage of obstetricians in Pennsylvania, and what is your group trying to do about it?

Answer: There’s a shortage because our state’s unreasonable malpractice laws are chasing doctors away. We’re trying to loosen those overly restrictive laws. Doing so would allow thousands of pregnant women to find a local obstetrician who can help in case of a medical emergency.”

Question 2: How big of a problem is this in Pennsylvania?

Answer: It’s a huge problem. You know, I met a 26-year-old woman recently who was in her seventh month of pregnancy last year when she went into early labor. The paramedics got there in time but didn’t have the skills to help when her baby was unable to breathe. Her son died, and he probably would have survived if her skilled obstetrician worked nearby. I’m hearing far too many of those stories lately, and we need to change these malpractice laws immediately to prevent any more of these tragedies from taking place.

Question 3: What do you say to those who believe that it’s a good idea to keep tough malpractice laws in place?

Answer: I would remind them that more than 18,000 women of childbearing age in Pennsylvania live at least 100 miles from the closest obstetrician, which places them at great risk. Having your doctor an hour away is kind of like keeping your Band-Aids at a friend’s house—they’re useless when you need them most. It’s a dangerous and sometimes life-threatening situation, and something has to change.

-------------

In question one, the spokesperson answered using a message. For question two, the spokesperson began with a story and then transitioned back to the message. To answer the third question, the spokesperson used a statistic followed by a sound bite.