from The Nine Lives of Charlotte Taylor · Sally Armstrong

“Land, bloody land—thanks be to God.”

— Sally Armstrong, from The Nine Lives of Charlotte Taylor (2006)

Chapter VIII

Migration and Exile

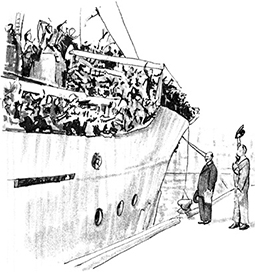

A nation built by immigrants on Indigenous land, Canada has become a multicultural, pluralist country. Even its earliest inhabitants likely came to it from other continents. Prior to the 1960s, when aircraft began to predominate on international routes, migrants came primarily by ship into the great sea ports on the Pacific and Atlantic coasts. The sea is therefore an overarching settlers’ experience. They came as entrepreneurs in the fur trade, as “daughters of the King” to be brides for the settlers of New France, as indentured workers from China and Japan, as displaced persons and war brides after the European wars. Following World War II, they came in response to successive government policies of immigration that actively recruited workers in a variety of trades and professions. These policies changed over the years: from attempts to preserve the predominance of British and European “whites,” to a gradual broadening of “acceptable” nationalities. In time, too, an increasing number of political and economic refugees found new homes in this “promised land,” this “land of unlimited opportunities.” Yet, Canada’s record of dealing with refugee ships has sometimes been harsh. One thinks, for example, of the 1914 expulsion from Vancouver Harbour of the SS Komagata Maru with her 376 British subjects from the Punjab. Or again, of the event in 1939 when an anti-Semitic Canadian government refused to grant sanctuary to the ocean liner MV St. Louis, carrying 930 Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany. Other vessels with asylum seekers followed into the twenty-first century. Whatever the challenges, neither the journey nor the resettlement process has ever been easy: even once having gained a foothold, some migrants may still encounter racism, marginalization, extradition—even exile.

The Voyage of Paul Le Jeune, 1632

Francis Parkman (1823–1893)

The storm-tossed ship that brought Paul Le Jeune, Superior of the Jesuit mission in Canada, to New France in 1632, carried a fervent missionary and educator. He spent seventeen years in the colony, avidly learning various Indigenous languages and teaching, not only among the Hurons, but also among the children of local African slaves. His descriptive anthropological account of the Hurons, and his personal recollections of the cold, hunger and conflicts he endured, are recorded in the Relations.

It was then that Le Jeune had embarked for the New World. He was in his convent at Dieppe when he received the order to depart; and he set forth in haste for Havre, filled, he assures us, with inexpressible joy at the prospect of a living or a dying martyrdom. At Rouen he was joined by De Nouë, with a lay brother named Gilbert; and the three sailed together on the eighteenth of April, 1632. The sea treated them roughly; Le Jeune was wretchedly sea-sick; and the ship nearly foundered in a gale. At length they came in sight of “that miserable country,” as the missionary calls the scene of his future labours. It was in the harbor of Tadoussac that he first encountered the objects of his apostolic cares; for, as he sat in the ship’s cabin with the master, it was suddenly invaded by ten or twelve Indians, whom he compares to a party of maskers at the Carnival. Some had their cheeks painted black, their noses blue, and the rest of their faces red. Others were decorated with a broad band of black across the eyes; and others, again, with diverging rays of black, red, and blue on both cheeks. Their attire was no less uncouth. Some of them wore shaggy bear-skins, reminding the priest of the pictures of St. John the Baptist.

After a vain attempt to save a number of Iroquois prisoners whom they were preparing to burn alive on shore, Le Jeune and his companions again set sail, and reached Quebec on the fifth of July. Having said mass, as already mentioned, under the roof of Madame Hébert and her delighted family, the Jesuits made their way to the two hovels built by their predecessors on the St. Charles, which had suffered woeful dilapidation at the hands of the English. Here they made their abode, and applied themselves, with such skill as they could command, to repair the shattered tenements and cultivate the waste meadows around.

—from The Jesuits in North America in the Seventeenth Century (1897)

The Bitter Taste of Freedom

Suzanne Desrochers (1976– )

Between 1663 and 1673 some nine hundred young women, known as the filles du roi, arrived in New France as wards of King Louis XIV. Provided with a small dowry, they were sent at state expense to become wives to the bachelors of the colony. Over time, their arrival achieved the desired effect. Whereas in 1663, there had been one woman to every six men, some twenty years later the sexes were about equal in number and the population had burgeoned. In the novel by Desrochers, Laure Beausejour is an indigent woman from the notorious Salpêtrière hospital and prison in Paris.

Beyond, at some distance into the sea, is the ship they will board for Canada. Laure doesn’t know if it is the cold misty air or terror at what lies ahead that makes her shiver. The boat, although one of the largest of its type, looks fragile, almost ridiculous, against the immense backdrop of the ocean. Laure has heard that early summer is the best time to undertake this journey to New France. Attempted too early or too late, their vessel would be shattered on rocks along the coast before they even reached the cruel centre of the North Atlantic …

The passengers are gathered in the hold at dusk for their dinner. The cook’s helpers, each carrying an end of the iron cauldron, descend below. One of the Jesuit priests comes out from behind his chamber curtain and heads upstairs for the captain’s table. The captain has his apartment and deck that looks out over the water. A few members of the nobility and the clergy, each with their own compartment below deck separated by a curtain from the public area, go up each night to dine with the captain. In the hold, along with the three hundred or so passengers, are the ship’s livestock. The animals are separated from the passengers by the boards of their pen, but the dirty straw makes its way through the cracks into the general filth of the ship’s bottom, and the smell of the animals permeates the air. A few of the sheep, cattle, and chickens are destined for the colony, but most are to be eaten during the crossing. But the animals are not intended for the indentured servants, ordinary soldiers, and women from the General Hospital. One calf was already killed for the first feast in the captain’s chamber. The passengers grumble that they hope the notables will be quick about eating the animals, as they are tired of sleeping with the smells and bleating of a stable.

Between the passenger hold, or the Sainte-Barbe as it is called, and the captain’s quarters is the entrepont [’tween-decks]. This is where the mail for the colony is kept, including letters from the King to the Intendant and the Governor. These bags are weighed down with cannonballs and are to be thrown overboard if their ship is accosted. In addition, there are religious supplies for the orders of New France, bolts of cloth, wooden furniture, dishes, tools, books, paper, spices, flour, oil, and wine, as well as the passengers’ rations for the journey: sea biscuits and lard in barrels, beans, dried cod and herring, olive oil, butter, mustard, vinegar, water, and cider for when the fresh water supply runs out or becomes too putrid to drink. If the passengers wanted additional supplies for the journey, they were responsible for packing them in their luggage. The girls from the Salpêtrière have nothing more with them …

Although they are crowded into a hold that is smaller than any of the dormitories at the hospital, Laure suddenly feels that there is a vast expanse around her. She doesn’t mind so much that she has no delicacies to add to her dinner plate. She spoons the monotonous mush into her mouth, savouring the cool thickness of it, because mixed in somewhere with the dry biscuits and fishy stench of her meal is the taste of freedom.

—from Bride of New France (2011)

A Hard Chapter in the Book of History

Antonine Maillet (1929– )

In 1763, the return of peace between the English and the French in North America was followed by a migration of Acadians returning to their homeland from enforced exile in the American colonies. Of the approximately three thousand who returned, most began their lives anew in the unsettled areas of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia; to this day, they represent a strong cultural force in Canada’s national fabric. Whereas the deportation had been conducted in overcrowded schooners, individuals generally returned by land. Maillet’s fictional widow, Pélagie, piling her cart high with family and belongings, epitomizes the courage and endurance of those who undertook the long trek home from exile. But the memory of the day of deportation is ever with her.

Exile is a hard chapter in the book of history. Unless one turns the page.

Pélagie had heard tell that all along the coast, in the Carolinas, in Maryland, and further north, Acadians from Governor Lawrence’s schooners, who, like her, had been dumped off at random in creeks and bays, were little by little resetting their roots in foreign soil.

“Quitters!” she couldn’t help shouting up at them from across the Georgia border.

For roots are also one’s own dead, and Pélagie had left behind, sown between Grand Pré and the English colonies to the south, father and mother, man and child, who for fifteen years had been calling her every night: “Come on back!”

Come on back!

Fifteen years since that morning of the Great Disruption. She was a young woman then, just twenty, no more, and already with five offspring hanging to her skirts … four to be exact, the fifth on the way. That fateful morning had found her in the fields, where her oldest boy, God rest his soul, had summoned her with his shouts of “Come on back! Come on back!” His cries clung to her eardrums. Come on back … and she saw the flames climbing the sky. The church was on fire. Grand Pré was on fire, and the life she had let run free in her veins until then suddenly boiled up under her skin and Pélagie thought she would burst. She ran, holding her belly, leaping over the furrows, her eyes fixed on her Grand Pré, that flower of the French Bay. They were already piling families into the schooners, pell-mell, throwing LeBlancs in with Héberts and Héberts with Babineaus. Bits of the Cormier brood seeking their mother in the hold, where the Bourgs were calling the Poiriers to look after their little ones. From one ship to another, Richards, Gaudets, Chiassons stretched out their arms toward fragments of their families on other decks, crying, “Take care of yourself! Take care,” their cries carried out by the swell to the open sea.

So it is when a people departs into exile.

And she, Pélagie, with the shreds of the family she had managed to save from the Great Disruption, had landed on Hope Island in the north of Georgia. Hope Island! Only the good omen in the name had kept this woman, this widow of Acadie with her four orphans, alive. Hope was a country, a return to the paradise lost.

—from Pélagie: The Return to Acadie (French original, 1979. English translation, 1982)

Do Not Trust Large Bodies of Water

Lawrence Hill (1957– )

Born in eighteenth-century West Africa, Aminata Diallo was abducted from her village and sold into slavery to an American plantation owner. Hill’s novel traces her appalling odyssey from Africa to the United States, to supposed “refuge” in racist Canada, and eventually her return to Sierra Leone in a futile bid for freedom on the continent of her birth. In her final years, living in London, sought after by the abolitionists for the eloquence she can bring to their movement, Aminata looks back on her life of abuse, denigration and extraordinary resilience. She reflects on sea voyages she has known, and the horrors they evoke for her.

Let me begin with a caveat to any and all who find these pages. Do not trust large bodies of water, and do not cross them. If you, dear reader, have an African hue and find yourself led toward water with vanishing shores, seize your freedom by any means necessary. And cultivate distrust of the colour pink. Pink is taken as the colour of innocence, the colour of childhood, but as it spills across the water in the light of the dying sun, do not fall into its pretty path. There, right underneath, lies a bottomless graveyard of children, mothers and men. I shudder to imagine all the Africans rocking in the deep. Every time I have sailed the seas, I have had the sense of gliding over the unburied.

Some people call the sunset a creation of extraordinary beauty, and proof of God’s existence. But what benevolent force would bewitch the human spirit by choosing pink to light the path of a slave vessel? Do not be fooled by that pretty colour, and do not submit to its beckoning …

Each rising sun saw more people die. We called their names as they were pulled from the hold. Makeda, of Segu. Salima, of Kambolo. Down below, at least, I couldn’t hear bodies hitting the water. Although the hold was dark and filthy, I no longer wanted to see the water, or to breathe the air above.

After what seemed to be several days, the toubabu [whites] started bringing us back up on deck in small groups. We were given food and a vile drink with bits of fruit in it. We were given tubs and water to wash ourselves. The toubabu burned tar in our sleeping quarters, which made us choke and gag. They tried to make us wash our sleeping planks, but we were too weak. Our ribs were showing, our anuses draining. The toubabu sailors looked just as ill. I saw many dead seamen thrown overboard without ceremony.

After two months at sea, the toubabu brought every one of us up on deck. Naked, we were made to wash. There were only two-thirds of us left. They grabbed those who could not walk and began to throw them overboard, one by one. I shut my eyes and plugged my ears, but could not block out all the shrieking.

Some time after the noise ended, I opened my eyes and looked out at the setting sun. It hovered just over the horizon, casting a long pink path across the still water. We sailed steadily toward the beckoning pink, which hovered forever at arm’s length, always close but never with us. Come this way, it seemed to be saying. Far ahead in the direction of the sun, I saw something grey and solid. It was barely visible, but it was there. We were moving toward land …

And so it happened that the vessel that had so terrified us in the waters near our homeland saved at least some of us from being buried in the deep. We, the survivors of the crossings, clung to the beast that had stolen us away. Not a soul among us had wanted to board that ship, but once out on open waters, we held on for dear life. The ship became an extension of our own rotting bodies. Those who were cut from the heaving animal sank quickly to their deaths, and we who remained attached wilted more slowly as poison festered in our bellies and bowels. We stayed with the beast until new lands met our feet, and we stumbled down the long planks just before the poison became fatal. Perhaps here in this new land, we would keep living.

—from The Book of Negroes (2007)

Land, Bloody Land—Thanks Be to God

Sally Armstrong (1943– )

Blending history, lore and imagination, Sally Armstrong’s novel re-creates the character of her indomitable great-great-great-grandmother, an early settler of New Brunswick’s Miramichi Valley. In 1775, strong-willed Charlotte Taylor ran away from her English home with her lover, the family’s black butler. Following his untimely death shortly after their arrival in Jamaica, an impoverished Charlotte accepted passage on a ship bound for the Baie des Chaleurs in northern New Brunswick—a land she would claim as her own. In 1980 a granite headstone on Charlotte’s grave proclaimed her “The Mother of Tabusintac.”

She is on her way back to her cabin when the coast comes into clear view. “Land, bloody land—thanks be to God,” Charlotte cries. Soon they steer around the high cliffs of Miscou still being swept by a stiff Atlantic wind and suddenly sail into the calm of the Baie des Chaleurs. Charlotte catches her breath at the sight of a land that captures her soul. A beautiful wilderness lies before her. Forests of fir trees drop off into fields of glistening seagrass that wave over long, sandy beaches. The water around her is teeming with fish. [Able seaman] Will is at her side and tells her the huge marine mammals with the horizontal flukes on their tails are called whales. They move like undersea mountains, riding up to the surface and slipping out of sight again. The smaller ones with tusks are walrus, he says. The cod are so plentiful, she thinks, she could scoop them from the water with her hands. She can hardly believe the long journey from England to the West Indies and now to this place called Nepisiguit is over. Standing in awe at the ship’s rail and remembering defiantly what has gone before, she vows, “I will make my own way.”

—from The Nine Lives of Charlotte Taylor (2007)

At the Rail

Alice Munro (1931– )

Alice Munro’s short story “The View from Castle Rock” is a semifictitious re-telling of the immigration to Canada in the early nineteenth century of her Scottish ancestors. Their long sea journey begins in the harbour of Leith, on the 4th of June, 1818. It evokes the experience of all who left their country of origin to make a new life in this vast land. Marked by birth, death, anxiety, doubt, homesickness and hope, the turbulent crossing is also an emotional divide that looks back to what once was—and is now forever gone—and forward to the unknown.

And on that same day but an hour or so on, there comes a great cry from the port side that there is a last sight of Scotland. Walter and Andrew go over to see that, and Mary with Young James on her hip and many others. Old James and Agnes do not go—she because she objects now to moving herself anywhere, and he on account of perversity. His sons have urged him to go but he has said, “It is nothing to me. I have seen the last of the Ettrick so I have seen the last of Scotland already.”

It turns out that the cry to say farewell has been premature—a grey rim of land will remain in place for hours yet. Many will grow tired of looking at it—it is just land, like any other—but some will stay at the rail until the last rag of it fades, with the daylight.

“You should go and say farewell to your native land and the last farewell to your mother and father for you will not be seeing them again,” says Old James to Agnes. “And there is worse yet you will have to endure. Aye, but there is. You have the curse of Eve.” He says this with the mealy relish of a preacher and Agnes calls him an old shite-bag under her breath, but she has hardly the energy even to scowl.

Old shite-bag. You and your native land.

Walter writes at last a single sentence.

And this night in the year 1818 we lost sight of Scotland.

—from “The View from Castle Rock” in The View from Castle Rock (2006)

Landfall in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, 1833

William Kilbourn (1926–1995)

Among the many migrants crossing the Atlantic in the early nineteenth century was an ambitious, diminutive Scot who would become one of the most colourful politicians and parliamentarians in Canada: William Lyon Mackenzie (1795–1861). A fiery journalist and businessman with a forceful cast of mind, he had first arrived in Upper Canada in 1820. Here he established The Colonial Advocate, a newspaper advocating reform of political life then dominated by the Family Compact with its grip on privilege, politics and wealth. His advocacy ultimately catapulted him into leading the Rebellion of 1837, an abortive armed revolt against the Canadian establishment. In 1832 he had returned to England in order to present his supporters’ grievances before the imperial government and to visit his native Dundee for the last time. His voyage back to Canada in 1833 matured his thoughts on the experience of migration, and on the political path that lay ahead.

The greater part of the Mackenzies’ fellow travellers on the return journey were not now returning British officials or businessmen, but poor emigrant families, crammed into pitching, choleric steerage quarters often occupied by timber or wheat on the eastward voyage, men and women and children who had given up forever the familiar hardships and comfortable custom-bound certainties of a thousand-year-old village for the hope and terror of the unknown. Mackenzie no longer entertained himself with confident hopes and thoughts about the omniscient benevolence of the persons who ruled the Empire, nor was he as certain as he had been at twenty-five on his first adventure on the Atlantic that only a Mackenzie knew how to be loyal. This trip meant committing himself as irrevocably to the New World as the humble folk that travelled with him.

Seven weeks out of port, at length, from the infinity of sky and sea came the land. For the emigrant for whom the village over the next hill meant “far” and the market town, for practical purposes, the end of the world, the first sight of their adopted country, where it did not freeze the senses into incomprehension, must surely have been awesome. Day after day the great shores of the gulf lay aloof from the frail busy society of the small ship, now all but disappearing from sight, now pressing in until the sheer black perpendicular mile of Capes Trinity and Eternity skidded vertiginously above them. How could anyone who knew the Thames or the Dee, who judged rivers by their human, civilized banks, accept the St. Lawrence? Only a few miles from where these others join the sea, kings have ridden on their waters—Saxon Edgar rowed by his thanes; Elizabeth in her royal barge greeted by Leicester; gouty periwigged George saluted by the “Water Music” of his court composer, Mr. Handel. But the coming together of the St. Lawrence and the Atlantic is hooded in the perpetual mists of the sub-Arctic.

Into the high sun of the gulf, the inhuman tallness of the blue and cirrocumulus sky, it is the same. Islands a day’s journey in the passing lie like the sleeping form of some species of monster unknown to Greek mythology or some giant never met by the gods of Valhalla. Beyond, on the shore, a forest bleaker by far than the haunted Teutonic woods that scared the Romans so. And the shore itself, the edge of a continental shield that would sternly test the man who believed he was the measure of all things. Gulf, sky, shore, each the infinitely receding and advancing perspective in the brain, the rim of madness, in a land still unthinkably abstract and virgin.

—from The Firebrand: William Lyon Mackenzie and the Rebellion in Upper Canada (1956)

Ghosts of History

Ingrid Peritz

The interweavings of memory, archaeology and forensic sciences can reinforce one’s relationship with the sea. Such is the case when relics of a nineteenth-century marine disaster came to light in Gaspé, Quebec, in 2011. The two-masted brig Carricks had sailed from Ireland in March 1847 carrying emigrants from the Irish estates of Lord Palmerston. On 28 April she ran into a heavy snow-laden storm in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and foundered on the shore near Cap-des-Rosiers. According to a contemporary report, the ship “went to pieces in the course of two hours.” Forty-eight of the approximately 176 passengers survived.

The Carricks left Sligo, Ireland, with almost two hundred passengers and crew, completing the transatlantic voyage before foundering off Cap-des-Rosiers. Accounts vary, but most report the deaths of as many as one hundred twenty passengers. The dead—weakened by cold, hunger and exhaustion—were said to be strewn along the beach the following day, then buried, anonymously, in a common grave nearby.

“For a whole day two oxcarts carried the dead to deep trenches near the scene of the disaster,” author Margaret Grant MacWhirter wrote in a book [Treasure Trove in Gaspé and the Baie Des Chaleurs] published in 1919. “In fall, the heavy storms sweep within sound of the spot. Thus peacefully, with the requiem of the waves and winds, they rest.” A half-century after the disaster, the parish of St. Patrick’s in Montreal erected a stone marker at Cap-des-Rosiers to the victims whose bodies were recovered and interred. “Sacred to the memory of one hundred eighty seven Irish immigrants from Sligo … eighty-seven are buried here,” its inscription reads.

The bones that surfaced in May [2011] were found near the monument, said Michel Queenton, a manager with Parks Canada—Cap-des-Rosiers lies within Forillon National Park. The coastline has been affected by erosion and heavy tides, the forces that exposed the human remains. However, a Parks Canada archaeologist says the precise spot of the Carricks’ burial ground was never documented, and it’s not known if it lies at the monument site. Some accounts say the bodies were interred further up the coast in a church cemetery …

“There is a strong probability the bones come from the communal grave,” said Geneviève Guilbault, a spokeswoman for the coroner’s office. “We want to be sure it’s the case.”

That prospect has stirred up the ghosts of history for those touched by the tragedy. Georges Kavanagh grew up within walking distance of the monument to the Carricks, and for him it has always been hallowed ground. His ancestors, Patrick Kavanagh and Sarah McDonald, came to the same shores aboard the Carricks (also referred to sometimes as the Carrick or Carricks of Whitehaven). They survived the harrowing transatlantic voyage with their 12-year-old son, but five daughters perished.

Georges Kavanagh, a unilingual francophone, feels a strong pull to the story of his Irish forebears, and he travelled to Sligo last year [in 2010] to connect with his roots. He says local oral history always placed the Carricks grave next to the monument, and if the bones prove to be those of the victims, they deserve a proper burial. “I consider that to be something of a sacred site,” the 71-year-old said from his home in Gaspé, about fifty kilometres from the monument, which he visits regularly. “To think that so many perished in a shipwreck just a few steps from their promised land. I have great admiration for what they tried to do, leaving everything behind for the hope of better living conditions.”

The Carricks was one of hundreds of migrant ships bound for the port of Quebec City in 1847, the darkest year of the famine in Ireland. The voyage required a stop at the quarantine station of Grosse-Île, where many refugees met their deaths from disease. Nearly four hundred ships sailed that year toward Quebec, the main immigrant gateway into Canada, filled overwhelmingly with Irish passengers. One in five never made it.

—from “Remains of a 19th-century tragedy?” in The Globe and Mail, 20 July 2011

Point of Entry

Jane Urquhart (1949– )

Grosse Île, in the mouth of the St. Lawrence River, served as a quarantine station for the port of Quebec from 1832 to 1937. Its early years witnessed the appalling fate of thousands escaping the Great Irish Famine of 1845–1849. Weakened by malnutrition, disease and filthy overcrowded ships, many who survived the nightmare of the transatlantic crossing died of cholera and typhus at Grosse Île. In 1847, at the height of the famine, over 7,500 were buried in the Irish Cemetery there. Today the Irish Memorial National Historic Site at Grosse Île commemorates the importance of immigration to Canada. Yet in his poem, “Grosse Isle,” poet Al Purdy recalls the past horrors of the place: “—a silence here like no mainland silence / at Cholera Bay where the dead bodies / awaited high tide and the rough kindness / of waves sweeping them into the dark.” In her novel, Away, Jane Urquhart writes of one Irish child who survived.

What the child had forgotten and would not remember until years later were the crowded docks of Larne and the journey there, the suffering, starvation, the desperate throngs on the wharf. He had forgotten the dark belly of the ship where no air stirred and, as the weeks passed, the groans of his neighbours, the unbearable, unspeakable odours, his own father calling for water, and the limp bodies of children he had come to know being hoisted through the hatch on ropes, over and over, until the boy believed this to be the method by which one ascended to heaven. He had forgotten his own sickness which drew a dark curtain over the wet, foul timbers of the ship’s wall and the long sleep that had removed him from the ravings of the other passengers until he wakened believing that the shrieked requests for air and light and liquid was the voice of the abominable beast, the ship that was devouring a third of the flesh that had poured into its hold. And after ten weeks crouched on the end of his parents’ berth on the New World, and six weeks confined to a bed with five other children at the quarantine station at Grosse Isle (some lying dead beside him for half a day), he had forgotten how to recall images, engage in conversation, and how to walk.

—from Away (1993)

The Alchemy of Immigration

Derek Lundy (1946– )

Fading photographs, yellowing letters and poignant memoirs are gold for the genealogist. For an immigrant country like Canada in particular, they are life-lines into the past. They help us recapture our identity, grasp our traditions and understand our roots. Emerging from the mists of a lengthy sea voyage these links can gain mythic dimensions. Derek Lundy begins his search for the past by contemplating a photograph of his great-great-uncle Benjamin, taken in 1895 on Salt Spring Island, BC, and tracing Benjamin’s journey from Ireland, and around Cape Horn, to British Columbia.

It was quite a journey, when you came to think of it. Immigrants to North America, including members of my own family, did it all the time—it was the quintessential immigrant experience—and that made it seem commonplace. But what an alchemy! The voyage away from the confines of European class, accent, religion, imperial diktat and the claustrophobic “close-togetherness” of everything to the space and light of the New World, its even-handed presentation of the possibility of success and failure. It was like the first true deep breath of a person’s life. Although he hadn’t followed the immigrant’s usual route—at first, perhaps, hadn’t even intended to immigrate at all—Benjamin had eventually made that leap too. I wanted to find out more about the man in the photograph, and at least part of the story of his trek from a two-up, two-down workers’ house in the Irish Quarter of Carrickfergus, under the shadow of a Norman-English castle in occupied Ireland, to become a landowner on an Edenic island in the Northwest rainforest.

It seemed to me entirely apt that Benjamin’s self-displacement from one species of existence to another had been accomplished by means of a sea voyage under sail. He changed his life, made it new, by crossing oceans to a new world. At the same time, his journey of six months on a wind ship, like all such passages, was a sea change in itself …

Each one was unique. From the moment the sailing ship up-anchored or unmoored, or dropped its tow, and began to move under the force of wind on sails alone, everything was thrown into the balance. No one could foretell the incidence or shape of the great things to come: storms, fire, stranding, collision, ice, Cape Horn’s disposition, the severity and duration of the inevitable struggle ahead. Nor was it possible to predict from moment to moment what claims, burdens, ultimatums the wind and waves would bring down on the ship and its crew. Every decision to take in or set more sail, each turn of the wheel in heavy seas, the speed and skill with which seamen hauled or furled, spliced or lashed, all the ways of devotion hour by hour, or even minute by minute, by which the ship was continually made able to sail on, or indeed to survive, in the endless chaos of the sea—all these were subject to chance and laden with the possibility of failure or ruin …

Benjamin’s passage as a sailor before the mast aboard the Beara Head [which he joined in May 1885] is, in part, the mere account of a young man learning the ropes; standing his watches; following orders; enduring cold, exhaustion and danger; helping to save the ship and himself; becoming a seaman. He is also a young man who, in the process of doing all that, learns the eternal lessons of the sea, which is to say that he finds out the sort of man he is, and that he is capable of doing things that, before or even after he did them, seemed almost unimaginably difficult and perilous. And although he is unaware of it, Benjamin is on a voyage freighted with the meanings and burdens of a whole world giving way to another.

—from The Way of a Ship: A Square-Rigger Voyage in the Last Days of Sail (2002)

Towards Gam Sun—Gold Mountain

Judy Fong Bates (1949– )

The Chinese Head Tax was imposed on all immigrants from China between 1885 and 1923. Beginning at fifty dollars per person, it was raised to five hundred dollars in 1903—the price of a house in Canada, or the equivalent of two years’ salary in China. Despite the financial hardship the tax represented, Chinese men from impoverished villages continued to cross the Pacific under wretched conditions in the hope of a better life in the “Gold Mountain.” Ultimately, these dreams were dashed by the Exclusion Act of 1923 which barred all Chinese immigrants from Canada until 1947.

One year later, Hua Fan boarded the large steamship that carried him and dozens of other Chinamen across the Pacific to Gam Sun. A tall, pale-faced man with strange orange hair loomed over them, herding the crowd in the right direction. He shouted at them in an odd-sounding language and yanked their long black queues when he wanted their attention. Hua Fan couldn’t stop staring. He had never seen a person with so much hair on his face.

For twenty-two days, Hua Fan lived with other Chinamen at the bottom of the boat. Some of the men were returning for the second or third time. A few of them teased him as they looked him up and down. “What’s a skinny fellow like you going to do over there? You think the streets are paved with gold? The lo fons treat their dogs better than a Chinaman.” But he ignored their taunts. He never complained about the terrible food, the tossing of the ocean, or the mingling stench of unwashed bodies and vomit. Some of the boat uncles though were kind and a few of them taught him how to count to ten in English, to say “yes” and “no,” “how much” and “thank you.”

When the ship docked in the harbour at Salt Water City [Vancouver], most of the Chinamen stayed there. It was a bustling town, and already the Chinese had established a community. But Hua Fan had to go to the middle of the country, to a small town in northern Ontario, where his uncle operated a small hand laundry.

—from China Dog and Other Tales from a Chinese Laundry (1997)

Farewell, My Bandit-Princess

Wayson Choy (1939– )

For Chinese migrants the sea was both a route of hope to the much-touted Gold Mountain, which Canada seemed to promise, as well as the road of peace “homeward” back to China once they had died. According to tradition, the deceased were interred in Canadian soil for seven years, when their bones were disinterred, cleaned and packaged for return by ship. It was not uncommon for an elderly migrant to accompany the bones from Vancouver on this, their final voyage. It was a final farewell to a country whose racist policies and practices since the 1880s had marginalized them and blocked any hope of integration. In Choy’s novel, a young girl recounts the departure of her beloved storytelling uncle, Wong Suk, with a shipment of bones. He used to regale her with fairy tales of princes, princesses and their captivating adventures.

We were not allowed to go past the customs landing and departure gates. Everyone started to say goodbye. The dock felt unsteady under my feet; everything smelled like iodine and salt and the sky was bright with light. Father gave a man in a uniform some money to carry Wong Suk’s luggage past the gates. I could only look about me, robbed of speech, spellbound. I remember Father lifting me up a little to kiss Wong Suk on his cheek; he seemed unable to kiss me back. His cheek, I remember, had the look of wrinkled documents. He looked secretive, like Poh-Poh, saying nothing. I felt his hand rest a moment on my curls, then a crowd of people began to push by us.

“Hurry,” Father said, gently lifting the old man’s hand from my head …

The Empress’s whistle gave a loud, long, last cry, sent seabirds soaring into manic flight; the giant engines roared, churned up colliding waves; the dock shook. The ship began to pull away. I think I saw Wong Suk on the distant deck of the ship. Then, as in a dream, I was standing beside Wong Suk, felt his cloak folding around me under the late afternoon sky. We were travelllng together, as we had promised each other in so many of my games. I wondered how he felt, unbending his neck against the stinging homeward wind.

What wealth should a bandit-prince give his princess? Wong Suk once had asked me, as I turned and turned and his cloak enfolded me, with its dark, imperial wings. And I answered greedily, too quickly, my childish fingers grasping imaginary gold coins, slipping over pearls large enough to choke a dragon, gripping rubies the colour of fire … everything … for I did not, then, in the days of our royal friendship, understand how bones must come to rest where they most belong.

—from The Jade Peony (1995)

Voyage of the Damned

Irving Abella (1940– ) and Harold Troper (1942– )

In May 1939, the SS St. Louis was one of the last passenger ships to sail from Germany on the eve of World War II. Carrying over nine hundred Jewish refugees desperate to escape Nazi persecution, she was refused permission to land, first in Cuba, then in the United States, lastly in Canada; this left her captain no option but to return to her home port of Hamburg. By allowing bureaucratic indifference and political expediency to trump human decency, Canada effectively used the sea as a defensive moat, thereby condemning asylum seekers to the concentration camps where many of them perished.

On May 15, 1939, nine hundred and seven desperate German Jews set sail from Hamburg on a luxury liner, the St. Louis. They had been stripped of their possessions, hounded first out of their homes and businesses and now their country. Like many who had sailed on this ship before, these passengers had once contributed much to their native land; they were distinguished, educated, cultured; many had been well-off but all were now penniless. Their most prized possession was the entrance visa to Cuba each carried on board.

The Jews on the St. Louis considered themselves lucky—they were leaving. When they reached Havana on May 30, however, their luck ran out, for the Cuban government refused to recognize their entrance visas. None of these wretched men, women and children were allowed to disembark, even after they threatened mass suicide. The search for a haven now began in earnest. Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay and Panama were approached, in vain, by various Jewish organizations. Within two days all the countries of Latin America had rejected entreaties to allow these Jews to land, and on June 2 the St. Louis was forced to leave Havana harbour. The last hope was Canada or the United States, and the latter, not even bothering to reply to an appeal, sent a gunboat to shadow the ship as it made its way north. The American Coast Guard had been ordered to make certain that the St. Louis stayed far enough off shore so that it could not be run aground nor any of its frantic passengers attempt to swim ashore.

The plight of the St. Louis had by now touched some influential Canadians; on June 7 several of these, led by [University of Toronto professor] George Wrong and including B. K. Sandwell of Saturday Night, Robert Falconer, past-president of the University of Toronto, and Ellsworth Flavelle, a wealthy businessman, sent a telegram to Prime Minister Mackenzie King begging that he show “true Christian charity” and offer the homeless exiles sanctuary in Canada. But Jewish refugees were far from the prime minister’s mind. King was in Washington, accompanying the Royal Family on the final leg of its triumphant North American tour. The St. Louis, King felt, was not a Canadian problem, but he would, nevertheless, ask [under-secretary of state for External Affairs, O.D.] Skelton to consult on the matter with [minister of justice, Ernest] Lapointe and [director of immigration, Frederick Charles] Blair. Lapointe quickly stated that he was “emphatically opposed” to the admission of the St. Louis passengers, while Blair claimed, characteristically, that these refugees did not qualify under immigration laws and that in any case Canada had already done too much for the Jews. No country, Blair added, could “open its doors wide enough to take in the hundreds of thousands of Jewish people who want to leave Europe: the line must be drawn somewhere.”

And the line drawn, the voyagers’ last flickering hope extinguished, the Jews of the St. Louis headed back to Europe, where many would die in the gas chambers and crematoria of the Third Reich.

—from None Is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933–1948 (1983)

Stolen Boats, Stolen Lives

Joy Kogawa (1935– )

In 1942, in the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Canadian government forcibly removed some 20,000 Japanese Canadians from the Pacific Coast, and confiscated the fishing boats of all the fishermen among them. These classic vessels were then sold off at bargain prices to “whites.” Despite advice from the RCMP that these people posed no threat, racism and war hysteria had triggered the move. The action uprooted families and destroyed a community. Only gradually during the late post-war period have Canadians of Japanese ancestry returned to coastal towns like Steveston at the mouth of the Fraser River, which at one time had boasted forty-nine fish canneries. Today in the municipality of Richmond one of the canneries—and a restored Japanese home—serve as museums. In Kogawa’s historical novel Obasan (“Aunt”) the narrator ponders family photographs and reflects on the troubling days of the past.

Grandpa Nakane, “number one boat builder” Uncle used to say, was a son of the sea that tossed and coddled the Nakanes for centuries. The first of my grandparents to come to Canada, he arrived in 1893, wearing a western suit, round black hat, and platformed geta on his feet. When he left his familiar island, he became a stranger, sailing towards an island of strangers. But the sea was his constant companion. He understood its angers, its whisperings, its generosity. The native Songhies of Esquimalt and many Japanese fishermen came to his boat-building shop on Saltspring Island, to barter and to buy. Grandfather prospered. His cousin’s widowed wife and her son, Isamu, joined him.

Isamu, my uncle, born in Japan in 1889, was my father’s older half-brother. Uncle Isamu—or Uncle Sam, as we called him—and his wife Ayako, my Obasan, married in their thirties and settled in Lulu Island, near Annacis Island where Uncle worked as a boat builder …

One snapshot I remember showed Uncle and Father as young men standing full front beside each other, their toes pointing outwards like Charlie Chaplin’s. In the background were pine trees and the side view of Uncle’s beautiful house. One of Uncle’s hands rested on the hull of an exquisitely detailed craft. It wasn’t a fishing vessel or an ordinary yacht, but a sleek boat designed by Father, made over many years and many winter evenings. A work of art.

“What a beauty,” the RCMP officer said in 1941, when he saw it. He shouted as he sliced back through the wake, “What a beauty! What a beauty!”

That was the last Uncle saw of the boat. And shortly thereafter, Uncle too was taken away, wearing shirt, jacket, and dungarees. He had no provisions nor did he have any idea where the gunboats were herding him and the other Japanese fishermen in the impounded fishing fleet.

The memories were drowned in a whirlpool of protective silence. Everywhere I could hear the adults, whispering, “Kodomo no tame. For the sake of the children …” Calmness was maintained.

Once, years later on the Barker farm, Uncle was wearily wiping his forehead with the palm of his hand and I heard him saying quietly, “Itsuka, mata itsuka. Someday, someday again.” He was waiting for that “some day” when he could go back to the boats. But he never did.

And now? Tonight?

Nen, nen, rest my dead uncle. The sea is severed from your veins. You have been cut loose.

—from Obasan (1981)

My War-Bride’s Trip to Canada

Janet McGill Zarn, Scottish War Bride (1919–1992)

Following the end of World War II, some 48,000 women—90 percent of them from the British Isles—came to Canada as “war brides.” They made the eight-day voyage “across the Pond” aboard liners that had been converted to troopships for wartime service—among them the Aquitania, Britannic, Letitia, Queen Mary, Île de France, Mauretania, Samaria. On board, the women experienced overcrowding, seasickness and homesickness—offset by camaraderie, “mountains” of good food and a sense of adventure. For many landing at Pier 21 in Halifax, the Atlantic Ocean was a barrier to returning to the “mother country.” Yet the eight-day crossing also represented a gateway to new horizons and a role to play in the post-war awakening of a vast land. Recalling the ceremonial singing of “O Canada” as her ship docked in Halifax in January 1947, Gwyneth M. Shirley wrote: “And war brides awaiting sang along / Not sure of the words but liking the song. / Their voices floated across the sea; / Their story passed into history.” The Pier 21 Society Resource Centre has archived the war brides’ impressions. Today some one million Canadians are descended from them.

During the night we heard anchors weighed and by morning light saw we were out in the Irish Sea in the middle of a convoy. Those of us from around the Clyde were quite familiar with the underwater boom across the Firth from Cloch Lighthouse to Cowal, Argyll and had seen the freighters file out through the gap between the guard ships for the open sea but beyond that knew nothing except that the navy took over for protection from the subs, based on the French and Norwegian coasts. It was a wondrous sight you could never forget it, all those ships surrounding us in their designated positions travelling in a huge group across the face of the ocean. On a clear day we could count 80 or so vessels, the two passenger ships and as far as we could guess the rest were freighters and tankers, and dimly in the distance you could catch a glimpse of the naval escort. Though separated by a considerable distance we could wave each morning to the crews of the merchantmen, our port and starboard neighbors. We moved south along the Irish coast but after Fastnet it seemed our last link with home had gone for ever, even the gulls finally abandoned us!

On board in daylight hours women, children and servicemen could all mix freely, in fact one girl had her husband aboard and could visit with him during the day until lights out. Blackout was enforced after dark and we were not allowed out on deck; our “boss” was an army man and he was strict, woe betide you if he found that you were not carrying your gas mask, you’d be sent back to your cabin for it, actually no hardship as we’d been doing that for years! Lifeboat drill took place every morning around 9:30 though one morning the alarm did go off at 5:30 and was a bit frightening as we could hear shell-fire; probably a U-boat was around, we’ll never know. In a convoy you have no idea where you are in the ocean but we must have traveled south a long way as it turned very warm but we hit very heavy swells and there was a lot of sea-sickness. With only the minimum of medical help aboard we had more or less to take care of ourselves, the children didn’t seem to be affected as much as their mothers so it was pretty hard on them but you do recover fast. The crossing took about 8 days then one morning we woke to find the rest of the convoy all gone, just the two passenger ships travelling up the Nova Scotia coast. I suppose the rest went south to New York or maybe to Newfoundland. That morning we sailed into Halifax.

—from My War-Bride’s Trip to Canada – Britannic, April 1945

Burial at Sea

Nino Ricci (1959– )

Burials at sea are ancient rituals. In the early days, the remains of those who had died of disease or of battle wounds had to be disposed of quickly. In the best of times, it was done in a variety of ceremonies, some of them conspicuously impromptu. Naval ritual involved two components: military and religious; for civilians, however, prayers and solemn sentences sufficed. Traditionally, one placed the body in a coffin, or wrapped it in sailcloth. Both would be weighted down with lead shot. Nautical lore has it that the final stitch in the body-bag called for a needle through the nose, leaving little doubt that the “dearly beloved” was in fact quite dead. In Ricci’s novel, a mother dies in childbirth on her journey to Halifax, leaving her young son to observe her funeral at sea through a grieving child’s uncomprehending eyes.

But all these later events happened in a mist. Before the mist set in, though, I was granted a few final moments of clarity—time enough to witness my mother’s funeral, which took place the morning after her death, and which I was allowed to attend because no one, not even myself, had noticed that I was burning with fever. The funeral was held at the ship’s stern, where the sun deck normally was, though all the chairs had been cleared away now. The sun was just edging above a still sea, the air cold but the sky stubbornly clear; and despite the early hour a small crowd of passengers attended—the ones my mother had befriended, Mr. D’Amico, the grey-eyed German, the honeymoon couple, and several others who I did not recognize, and who stood a ways back as if they were afraid of being turned away. Antonio [the third mate] was there, and the captain, hats in hands, as well as a few of the other officers, the ship’s chaplain, Louisa, a sombre and sober Dr. Cosabene. But only Louisa and Mr. D’Amico and the honeymoon couple cried through the service; the others retained a stony silence, stiff and awkward, as if the bright sun and clear sky made them feel unnatural in their mourning.

My mother’s body, enclosed in a canvas sack and covered with an Italian flag, lay on a small platform that rose up above the rails and pointed out to sea. After the chaplain had read from his missal Antonio gave the eulogy. But I wasn’t following—there had been a mistake, the kind of thing where dead people were not dead or where they could sometimes come back to life again, like that, the way the wheat around Valle del Sole, snow-covered in winter, could suddenly be green again in the spring. In a moment, I was sure, my mother’s head would pop out of her sack. “Vittorio,” she’d say, eyes all squinty and lips pouting, “look at you, always so serious!” And everyone would laugh.

But now Antonio, his voice hoarse with emotion, was ending his eulogy; and after a long moment of silence a young frail-eyed officer began to play a song on a bugle, while we stood with our heads bowed. When he had finished the chaplain made a sign of the cross, and on a nod from the captain Antonio’s hand slipped over a lever beneath the platform that held my mother, hesitated there a moment, then finally wrenched the lever back, hard. The platform tilted sharply towards the sea and the canvas sack slid out suddenly from under the flag; but before I could hear it strike the sea’s surface my knees buckled beneath me, and my mind went blank.

—from Lives of the Saints (1990)

One Time I Crossed the China Sea

Nhung Hoang (1955– )

From 1975 to the mid-1990s, over three million people fled widespread human rights abuses in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. Hundreds of thousands fled by sea in small, often unseaworthy vessels—of these, tens of thousands perished. As the story of the “boat people” unfolded, Canada offered refuge through a vast program of voluntary sponsorship and government assistance. In 1986 the United Nations High Commission for Refugees awarded its prestigious Nansen medal to the Canadian people for welcoming the desperate Southeast Asian refugees. Nhung Hoang’s poem captures the terror experienced by the fleeing “boat people.” Although the second part of their journey to Canada was by air, it too was filled with the same uneasy mix of apprehension and expectation common throughout history to people seeking a better life in a new place.

One time I crossed

The China Sea,

Full of fear,

In a small boat,

Two typhoons,

High waves

Fierce winds,

Death was so close.

One time I flew

Over the Pacific Ocean,

Full of expectation,

For a new life,

Also full of uncertainty,

For the days in a new country.

—from Refugee Love (1993)