The Naval Prayer · Department of National Defence

“O Eternal Lord God, who alone spreadest out the heavens, and rulest the raging of the sea; who has compassed the waters with bounds until day and night come to an end; Be pleased to receive into thy almighty and most gracious protection the persons of us thy servants, and the Fleet in which we serve. Preserve us from the dangers of the sea, and from the violence of the enemy; that we may be … a security for such as pass on the seas upon their lawful occasions …”

—Excerpt from “The Naval Prayer,” Divine Service Book for the Armed Forces (1950), Department of National Defence

Chapter IX

A Noise of War

War on the high seas and the defence of home waters are central to the Canadian experience. Indeed, Canadian naval forces have been shaped by many converging dynamics since the creation of the Royal Canadian Navy in 1910. Not the least of these are geopolitical, domestic, economic, cultural and societal pressures. Arguably, even the navy’s early roots in the Battle of Hudson’s Bay (1697) and the War of 1812 on the Great Lakes have contributed to its lore. The history of “The Naval Service,” as it is affectionately known, is one of a seagoing force that serves the people and legitimate authority, and is underpinned by both nautical and spiritual values.

Profile of a Navy

Marc Milner (1954– )

The common perception of a navy is that of a fighting service. In time of war it protects the nation’s coasts and trade, and it carries the war to the enemy’s shore and attacks his vital maritime interests. But the public perception of navies as armed services designed to wage war belies their more mundane, and more customary, functions. Navies are among the most potent symbols of a state. They represent the extension of national power onto the untamed sea. In times of peace they patrol, assert sovereignty, enforce the rule of law, deter aggression, or show the flag. It is, after all, at sea—what the famous American naval historian and theorist Alfred Thayer Mahan called “the great common”—where the interests of all trading nations converge and overlap. And where, until recently, no globally recognized system except national navies has governed the actions of the unruly—of pirates, poachers, and slavers …

Since its founding in 1910 the Canadian navy has fulfilled all the basic tasks expected of naval forces. It defended hearth and home—and trade—in two major wars and during the Cold War. It has supported peacetime national initiatives, including participation in NATO and United Nations operations, extension of maritime and arctic sovereignty, protection of fisheries, enforcement of international treaties and law, and disaster relief at home and abroad. And, typically, the construction and maintenance of the Canadian navy has also been an important source of government expenditure, of industrial and economic development—and of political largesse.

In the course of its first century the Canadian navy has achieved some noteworthy milestones. During the Second World War, when Canada was, briefly, a great maritime state, its navy became—also briefly—the third largest in the world. In the Cold War the Canadian navy achieved equal international fame for its innovations in anti-submarine warfare. At the end of the twentieth century Canada remains an innovator in modern warship design and construction. In the process the navy staked out a vast area of national interest well beyond the existing territorial waters of the country. In time these areas evolved into Canada’s extensive 200-mile coastal economic zones, which included control over the rich Grand and Georges banks.

Sadly, because of the nature of the country, few Canadians ever see their navy and few know much about it. Fewer still, perhaps, would describe Canada as a great maritime state, much less a seapower in the traditional sense. Although Canada was and remains a trading nation, and most of its imports and exports go by ship, the vast majority of Canadians have no contact whatever with the sea that girds their nation on three sides. Moreover, through the twentieth century, Canada has been allied, formally or informally, with the dominant seapower: first Britain, then the United States. The requirement for a navy, if defence of trade and protection from invasion were its primary tasks, has been fleeting at best since 1900.

And yet, since Confederation in 1867, Canada has needed something to protect its off-shore interest. In the early years these concerns consisted of little more than enforcement of fisheries agreements. The assumption of a greater Canadian role in the country’s own defence after 1900 and the rising military threat from Germany provided the final impetus for establishing a proper navy only in 1910. Even so, the future of the new Royal Canadian Navy was anything but certain. Before the ink dried on the legislation, Canadians were arguing over what kind of fleet should be built and where, and for what purpose.

Canadians have been arguing about those issues ever since, and with good reason. Navies are expensive to build and maintain, yet they seldom engage in combat. Governments and taxpayers need to be convinced that the heavy, long-term investment fulfils some practical need. In peacetime that need has often been sovereignty, policing offshore areas and protecting marine resources. Navies also fulfil a remarkably useful diplomatic purpose. Warships remain the most moveable manifestations of a sovereign state yet invented. Their good-will visits, a tradition of long standing, carry a cachet unlike any other act—other than a formal state visit. As one recent Canadian ambassador to the Middle East observed: “In two days a visiting Canadian warship accomplished more than I could in two years.” Moreover, as the Canadian government discovered as early as 1922, when the fleet was sent to Nicaragua to help settle a debt, or during the turbot dispute with Spain in 1995 when the deployment of Canadian submarines was mooted, navies provide enormous reach and versatility. Perhaps for those reasons, at the end of the twentieth century the Canadian government seems sold on the utility of naval forces.

—from Canada’s Navy: The First Century (1999)

The Battle of Hudson’s Bay

Peter C. Newman (1929– )

When war between England and France broke out in the 1680s, raiding parties of both countries regularly stormed and captured each other’s trading posts. Under the brilliant command of Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville, the French defeated the British at the Battle of Hudson’s Bay (1697) and captured York Factory. The French 44-gun Pélican faced the 118 guns of the three English ships, Hampshire, Dering and Hudson’s Bay—and won. Since its founding in 1987, the Naval Reserve Division HMCS D’Iberville, one of twenty-four such divisions across the country, stands as a memorial to the life and exploits of this remarkable explorer and naval officer.

Caught between the English-held fort on land and English cannon facing him at sea, d’Iberville had two choices, surrender or fight—and for him that was no choice at all. He ordered the stoppers torn off his guns, sent his batterymen below, had ropes stretched across the slippery decks to provide handholds and aimed his prow at the enemy. As he swept by the Hampshire, Captain John Fletcher, its commanding officer, let go a broadside that left most of the Pélican’s rigging in tatters. At the same time, the two HBC ships poured a stream of grapeshot and musket fire into the Frenchman’s unprotected stern.

The battle raged for four hours. The blood of the wounded French sailors bubbled down the clinkerboards through the scuppers into the sea. The ship’s superstructure was reduced to a bizarre accumulation of shattered wood; a lucky shot from the Dering had blown off the Pélican’s prow so that she appeared dead in the water.

In a brief respite, when the two tacking flagships were close enough for the commanding officers to see one another, Fletcher called across from the Hampshire demanding d’Iberville’s surrender. The Frenchman made an appropriate gesture of refusal, and the English captain paid tribute to his opponent’s courage by ordering a steward to bring him a bottle of vintage wine. He proposed a toast across the gap between the two vessels, raising his glass in an exaggerated salute. D’Iberville reciprocated. The ships were so close and the two hulls had so many holes in them that the opposing gun crews could see into each other’s smoky quarters. Minutes later, d’Iberville came up on Fletcher’s windward quarter and let go with one great broadside, the storm of fire pouring into the English hull, puncturing her right at the waterline. Within three ship’s lengths, the Hampshire foundered, having struck a shoal, and eventually sank with all hands.

It was barely noon and the desperate splashing of drowning seamen still echoed in the freshening autumn wind as d’Iberville manoeuvred his crippled ship to direct the force of his guns against the Hudson’s Bay. The Company ship let go one volley and surrendered. During a squall, the Dering fled for shelter in the Nelson River. As the Pélican’s crew began boarding the vanquished Hudson’s Bay, a sudden storm came in off the open water, the shrieking wind melding with the screams of the wounded as the rough heaving of the ships battered their bleeding limbs against bulkheads and splintered decks. The Hudson’s Bay was lucky enough to be driven almost ashore before she sank, so that those aboard could wade to land, but the Pélican dragged useless anchors along the bay-bottom silt in the teeth of the hurricane-strength onshore winds. Finally, her rudder broken, she nosed her prow into a sandbar six miles from the nearest bluff. Her lifeboats had been shot away; rescue canoes from shore were swamped as soon as they were launched. The survivors were forced to swim ashore, towing the wounded on a makeshift raft of broken spars. Eighteen more men drowned, and the others stumbled on shore to find the inhospitable land swathed in snow, with nothing but a bonfire and sips of seaweed tea to comfort them.

—from Company of Adventurers, Volume I (1985)

Press Gangs and Privateers

Thomas Raddall (1903–1994)

The American War of Independence (1775–1783) began as a war between Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America. However, it soon escalated into a series of international conflicts which placed increasingly heavy demands on Britain’s Royal Navy. Impressment, now known as “shanghai-ing,” was a violent and often crude way of recruiting for naval service. During this time of upheaval, Halifax served as an important British naval port and fortification—her young men rounded up by dreaded press gangs to serve on British fighting ships.

At frequent intervals the fleet came in, and the Dockyard rang with the labours of shipwrights, calkers, blacksmiths, coppersmiths, riggers, and breamers. These were the days of the press gang, a common feature of Halifax life for half a century. A man-o’-war captain short of seamen was expected by his superiors to pick up his own recruits, and the easiest way was to send his men about the streets of the port seizing every unfortunate youth who fell in their path. These press gangs were armed with cudgels and cutlasses; resistance meant a broken head and later on a taste of the cat-o’-nine-tails to cure the recruit of his stubbornness.

To preserve the form of law it was customary for the admiral to obtain a press warrant from the council, who granted it under pressure from the governor on the ground that the press would rid the town of idle vagabonds. But the vagabonds knew well how to vanish at the first warning cry of “Press!” in the streets, and it was the countryman up to town for the market, the fisherman, the ’prentice boy, the young townsman out for an evening’s lark, who fell into the toils. Those with influential friends or employers could count on release later on, but they were few. For two generations of almost incessant war young Haligonians vanished into the lower decks of His Majesty’s ships, to die in distant battles, or of the scurvy, the typhus, or the yellow fever which in those days scourged the British service.

—from Halifax: Warden of the North (1948)

War Games

Michael L. Hadley (1936– ) and Roger Sarty (1952– )

War gaming has always been an integral part of military and naval operations. It involves imagination, innovation, anticipation, foresight—and sometimes a good sense of humour. It’s the old story of trying to anticipate answers to the question “what would happen if?” Perhaps the earliest Canadian war game took place off Halifax, the “Warden of the North,” toward the close of the nineteenth century—before Canada even had a navy, and depended upon Britain.

“The Latest Improvements in Scientific Warfare” reached Halifax on 6 July 1881 in what the Halifax Morning Chronicle called a “Grand Torpedo Attack.” The headlines announced a major test of a new weapon in the fortress town’s defences. Military authorities had timed this thrilling event to climax the governor general’s visit to the imperial town. Thousands of people thronged the shoreline, from Freshwater to Point Pleasant Park, and the slope up to the summit of the Citadel, with its commanding view of the harbour. Others watched the war game from boats, steamers, and tugs, while some four hundred more held tickets for the governor general’s vantage-point on George’s Island. How well could Halifax defend itself against assault forces from the sea? The military hoped to provide an answer with a realistic scenario.

The idea of the mock attack was simple. According to the well-briefed press report, “an enemy’s squadron, taking advantage of a thick fog, had passed the entrance to the harbour unperceived, and intended to take possession of the Dockyard and the magazines.” The defenders had meanwhile seeded the approaches with “torpedoes,” or what we now call mines. The lone corvette HMS Tenedos, a converted wooden steam sloop with two seven-inch rifled muzzle-loader guns, represented an enemy squadron. On this occasion she enjoyed the brilliant sunshine of a glorious July morning instead of the fog for which the war-game scenario called. The audience watched as Tenedos anchored off the first “torpedo” and sent a boat’s crew to reconnoitre the dangerous waters. Armed with grappling hooks for tearing the electric cables connecting the mines from their control station on shore, the men probed the channel. This was precisely the method that a secret German memorandum had recommended His German Majesty’s Ship (SMS) Elisabeth use to combat moored mines in Panama in 1878: either a steam pinnace with trawls or two rowboats moving abreast, with a weighted line suspended between them. But in the British exercise at Halifax the enemy “accidentally” exploded a mine, thereby awakening the garrison to its imminent danger and triggering a withering mock battle between the attacking “squadron” and the artillery ashore.

By all accounts the experiment was a great success. In the Chronicle’s words: “The roar of the heavy guns to the immediate spectators was perfectly deafening. The simultaneous explosion of … mines was a grand sight, producing novel sensations to those unaccustomed to torpedo displays. The sudden upheaval of large masses of water … carrying with it all kinds of debris, mud and fish … accompanied by the angry rumbling roar of the explosion gave the spectators a faint idea of the grandeur … and horrors of modern warfare.” But the tumult had destroyed all the mines. The make-believe enemy slipped through the cleared passage and reached its ultimate target. Halifax faced defeat. But for the moment that did not really seem to matter: the governor general had been “highly delighted and edified” by the operation.

—from Tin-Pots and Pirate Ships: Canadian Naval Forces and German Sea Raiders 1880–1918 (1991)

Off Coronel

Archibald MacMechan (1862–1933)

On 1 November 1914 Canada lost her first sailors to naval warfare: four midshipmen of the Royal Canadian Navy, from the first class of the Royal Naval College of Canada. The Battle of Coronel took place off the coast of Chile near the city of Coronel where Graf von Spee’s powerful East Asia cruiser squadron encountered Britain’s much inferior 4th Cruiser Squadron under Rear Admiral Christopher Cradock, RN, in HMS Good Hope. The Germans handily destroyed their opponents before proceeding to the Falkland Islands, where they themselves were destroyed on 8 December by a British battle-cruiser force. A bronze plaque at the entrance to the Coronel Library in the former Royal Roads Military College (now Royal Roads University) commemorates the deaths of Midshipmen Malcolm Cann, John V.W. Hateway, William A. Palmer and Arthur W. Silver.

In the stormy Southern sunset, great guns spoke from ship to ship;

Swift destruction, death, and fire leapt from iron lip;

Till two crushed and flaming cruisers vanished dumbly in the night,

Sank, nor left a soul behind to tell of that disastrous fight.

In the dark, they died, our comrades, and without a sign they passed

But they fought their guns and kept the Old Flag flying to the last.

Death is bitter in lost battle, but they died to shield the Right,

So they swept from that brief darkness into God’s eternal light.

—from Songs of the Maritimes: An Anthology of the Poetry of the Maritime Provinces of Canada (1931)

Wartime Shipbuilding

James Pritchard (1939–2015)

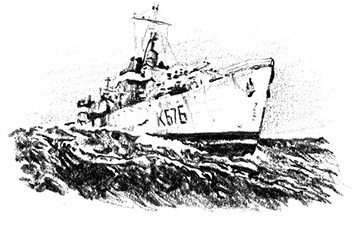

The title of the book from which this excerpt is drawn—A Bridge of Ships—is a graphic reminder of the vital importance of wartime shipbuilding. Canadian-built warships and cargo vessels of every description formed massive life-lines across the seas. In shipyards across the country Canadians not only built these essential warships and cargo vessels, but repaired and refitted them after their often gruelling voyages. The sites of most of these marine industries are lost to public memory today: yards like those at Prince Rupert and North Vancouver (BC), Lauzon (QC), Saint John (NB), Port Arthur (present-day Thunder Bay) and Collingwood (ON). Equally remote seem the shipyards and boat yards in the Great Lakes which, between 1940 and 1945, produced fifty Flower-class corvettes—the workhorses of the Battle of the Atlantic—as well as over a hundred minesweepers and fifty-nine Fairmile motor launches. At the peak of the war effort, Vancouver’s Burrard Shipyards typically employed fourteen thousand workers, including one thousand women. Welder E.H. Harris remembered those halcyon days in his “Shipbuilder’s Ballad”: “Each hour we spend in building, / The more ships can be put to sea; / A giant steel bridge of freedom / Built in the cause of liberty.”

The history of Canada’s shipbuilding industry during the Second World War is as astonishing as the history of the nation’s wartime navy. The personnel of both expanded by an order of fifty times. Yet, whereas the story of the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) is sufficiently well known as to arouse vigorous debates among historians, the history of Canada’s wartime shipbuilding industry remains virtually unknown …

Wartime shipbuilding had not required Canadian shipyards to develop an engineering design capacity. In the end, the typical Canadian yard was a large manufacturing concern without a design and development capability. The industry remained wholly dependent on what the British wanted built—the simplest ships possible—and on British naval architects and engineering talent. With few exceptions, wartime shipbuilding followed British plans and specifications. Little was conceptually new; in fact, the steam technology employed was more than a half-century old. Innovations and reorganization in the yards were limited to increased welding to replace riveting, often over the objections of British marine engineers and naval architects, and sometimes involved brilliant use of new machines such as “Unionmelt” welding on combustion chambers of Scotch boilers. Other improvements occurred outside shipyards among steel fabricators and machinery manufacturers …

Warship production, like other armaments, required a relatively sophisticated engineering industry and a machine-tool industry. Canada lacked both. Little original engineering design was carried out in Canada, which remained wholly reliant upon the United States and the United Kingdom for machine tools until 1942 … Although Canada developed and carried out a successful emergency program to construct escort vessels, it failed to develop a capacity to go beyond initial ship specifications. Much of the navy’s modernization crisis was due to its failure to learn from combat to modify its own escort ships. All improvements had to wait until they were received from the British Admiralty.

Ironically, the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN), which had been technologically challenged throughout the war, proved to be better positioned for the future than the shipbuilding industry. Since 1943 the navy had been maturing plans for its postwar fleet … Although the RCN still lacked a warship design capacity, at the end of the war it was swiftly acquiring one. These developments and the government’s response to the Cold War [1947–1991], rather than any wartime legacy, kept Canadian postwar shipbuilding alive …

Despite its magnificent achievement, Canada’s wartime shipbuilding industry left no lasting legacy. The great volume of ship production that Canada achieved was not planned in advance. It was forced upon the country during 1940 and 1941 by the desperate needs of war. Canadian North Sands, Victory, and Canadian types were designed for the sole purpose of providing as many ships as possible in the shortest time possible to move essential war cargos and supplies across the Atlantic faster than the enemy could sink them. That was the task, and it was accomplished.

—from A Bridge of Ships: Canadian Shipbuilding during the Second World War (2011)

Seapower

Joseph Schull (1906–1980)

During the crucial years of World War II (1939–1945) Canada’s navy served in dangerous waters from the Pacific to the Mediterranean. During the Battle of the Atlantic alone, Canadian warships escorted massive convoys between major ports in North America and Great Britain. As a fighting force, Canada’s navy kept the sea lanes open. In doing so it fought pitched battles with enemy forces, especially submarines, losing twenty-four warships to enemy action. Emerging in 1945 as a powerful maritime nation, Canada had owed her seagoing supremacy to an unprecedented confluence of forces: manufacturing and industry, shipbuilding, mobilization of people and supplies—and national will. In writing The Far Distant Ships as the government’s first official history of the navy, Schull aimed not only at providing a riveting account of Canada’s war at sea; he also argued for a “big-ship” post-war navy. Ultimately, modern technology and warfare irrevocably changed the old pattern; Canada now has one of the smallest navies in the world—yet one with a global mission.

“Those far distant, storm-beaten ships upon which the Grand Army never looked, stood between it and the dominion of the world (Alfred Thayer Mahan).” Mahan was writing of the army of Napoleon and the ships of Nelson. Yet his words apply unchanged to the war which began a hundred and thirty-four years after Trafalgar. When Hitler at the summit of his power looked westward from a conquered Europe, the long line of the Atlantic convoy and the grey menace of the Home Fleet rose, invisible and implacable, the barrier he was never to surmount.

Sea power made the conquest of the British Isles an essential for the mastery of Europe and a key to world rule. And sea power made that conquest an impossibility. Dingy, unseen tankers brought in oil for the Spitfires and Hurricanes over seas held open by the Royal Navy. Cargoes of food and supplies, rifles and cannon for the beaten armies returning from Dunkirk, came in by sea. Thereafter sea power—of the United States and Canada and of other nations as well as Britain, sea power moving both on wings and keels—made possible the gathering of mighty resources for the offensive. Sea power bridged the gulf between the old world and the new; linked farms and mines and factories, laboratories and blast furnaces and training camps, with the battlefronts. Sea power was the means of translating strength into accomplishment; the ability to mobilize and concentrate and thrust at the chosen time and at the vital point …

On the Atlantic, throughout the longest and most crucial struggle of the war, Canada’s navy grew to be a major factor. In almost every other naval campaign her ships or men were represented; playing frequently an obscure, sometimes a brilliant part. Their work was a share—and no more than a share—of the national effort. The men of the merchant ships wrote an epic which will not be forgotten while the nation remembers its past; and men toiling ashore performed daily impossibilities.

—from The Far Distant Ships: An Official Account of Canadian Naval Operations in the Second World War (1950)

The Maple Leaf Squadron

Author unknown

Sea shanties and nautical folk songs colour and communicate the seafarers’ life. In the nautical world, group singing accompanied many seamen’s tasks such as weighing anchor, rowing dories and whalers, and hauling sails. In the process, verses were added or dropped at will, and frequently shaped and re-shaped in order to deal with local circumstances. Such “occupational ballads” serve not only to bond a team of workers, but to create their characteristic mythologies. The zest of the performance—whether fantasizing on battle, rejecting authority and routine, or boasting of sexual prowess—captures youthful attitudes to lives that in wartime can be bitter and brief. Gallows humour frequently prevails. Such was certainly the case when depicting the life of convoy escorts during the Battle of the Atlantic (1939–1945).

Then here’s to the lads of the Maple Leaf Squadron,

At hunting the U-Boat it’s seldom they fail;

Though they’ve come from the mine and the farm and the workshop,

The bank and the college and maybe from jail.

Chorus:

We’ll zig and we’ll zag all over the ocean,

Ride herd on our convoy by night and by day.

Till we take up our soundings on the shores of old Ireland,

From Newfy to Derry’s a bloody long way.

We’re out from grey Newfy and off for green Derry,

Or swinging back westward while tall waters climb;

The grey seas roll round us, but never confound us;

We’ll be soon making port and there’ll be a high time.

So we’re off to the wars where there’s death in the making,

Survival or sacrifice, fortune or fame;

And our eyes go ahead to the next wave that’s breaking,

It’s the luck that’s before us adds zest to the game.

—Traditional

Down the Gangplank into the European Theatre of War

Earle Birney (1904–1995)

Some 368,000 Canadian troops served in Europe during World War II. They were transported overseas in scores of ships that had been converted from commercial liners in order to increase their carrying capacity. Some of them were as large as the 81,000-ton Cunard liner Queen Mary which reached speeds of 28.5 knots. When she sailed from Halifax with Winston Churchill on 27 August 1943 she carried 15,116 troops. While most ships sailed in convoy under naval escort, these “Monsters” as they were called in code, sailed independently. Given their high speed and manoeuvrability, and their secretly planned zigzag courses, they could outrun enemy submarines. Troops on board were never informed where they were going, nor by which route. It is in such a situation that Earle Birney sets his n’er-do-well, accident-prone, quixotic hero. Birney’s picaresque novel Turvey won the Stephen Leacock Memorial Medal for Humour in 1949.

At last the order raced through the camp and they were stuffed into another train and shunted into Halifax. There was a long day of standing in an embarkation shed rumbling with trucks and echoing with officers. Then with his overcoat buttoned by command to the neck, and his respirator on his left side and his water bottle full of coca-cola on his right, and his haversack slung on his left, and his rifle on his right, and his pack on his back, and his tin helmet joggling on his head, and ammo pouches full of chocolate bars across his chest, and his dunnage bag in his left hand, and a berth card and a mess card and a tag and an extra roll of issue toilet paper in his right, Turvey boarded the grey transport. Though the thought came to him that the Atlantic was even deeper than the transit camp, he descended into the ship’s bowels, smelling already of kippers and boiled cabbage, and struggled to the top of a four-tier bunk, with something like relief.

The Atlantic, it is true, proved even more monotonous than their waterlogged barracks: six days of zigzagging in a putty-coloured waste of waters, six days of life-boat drill and kit inspection and lining up for meals, seven queasy nights of rolling on an emaciated mattress in a man-packed hold. Since they were not in convoy, there was nothing to look at but the salt-chuck, of which Turvey thought there was far too much and all the same. Nor was he comforted by the ship’s name, Andes. It was such a heavy name, much heavier than water.

But somehow the Andes buoyed Turvey’s body safely, while his spirits, never easy to douse at any time, were sustained by his fairly consistent winnings at black jack and by the thought that he was approaching every moment nearer a glamorous new world …

And then with the seventh morning came sunlight on a bright green headland, and Catalinas in the air.

“Africa, like I said,” McQua muttered.

“Nerts. I bet it’s Greenland. Taint Nova Scotia anyway,” said a Haligonian.

“I see a castle,” Turvey shouted. “Maybe it’s Spain!”

“Why don’t you chaps get wise to yawselves. That’s Iahland dopes,” drawled the veteran Tank Sergeant.

Ireland it was, green as a pool table. And, in a few hours, the rockier coast of Scotland, real wrecks on English sandbars, destroyers circling a convoy, and the bombed docks of Liverpool. Turvey had arrived in a land where, if the tales of the Tank Sergeant and the warnings of the Security Officers were true, training schemes were conducted with live mines and honest-to-god shells, enemy spies listened in every restaurant, you didn’t dare scratch a match except behind blackout curtains, the ale was terrific, and the girls all blonde and all lonely. Britain, land of air-raids and thatched-roofed beer parlours—and Mac and the Kootenay Highlanders. A new land and a new Turvey, his crime-sheet cancelled in Halifax, and a shiny new pay book in his pocket in which the adjutant had forgotten to stamp any of his O-scores. Turvey straightened his helmet and marched down the gangplank into the European Theatre of War.

—from Turvey (1949)

U-69 Sinks the Ferry Caribou in Cabot Strait

Michael L. Hadley (1936– )

Among the major losses of the war years was the 266-foot, 2,222-ton Newfoundland ferry Caribou during her regular nightly crossing of the Cabot Strait. Her route ran the 110-mile stretch of open water between the Canadian National Railway’s railhead in North Sydney, Nova Scotia, and Port aux Basques, the western terminus of the Newfoundland Railway. Her courses cut across the convoy routes at a critical choke-point in the Battle of the Atlantic.

On the dark night of 13 October 1942 German submarine U-69 was lurking about for targets of opportunity in Cabot Strait. Its skipper knew that Canadian naval patrols and escorts faced heavy challenges: a harsh climate with its fog and gales; ice-choked passages in winter, and the severe oceanographic conditions that always seemed to favour the submarine. For here the fresh water of the St. Lawrence River mingled with the salt water of the sea, and produced protective layers under which a submarine could hide with impunity from probing sonar.

Ferries had been making regular runs between Sydney, Nova Scotia, and Port aux Basques, Newfoundland, since 1898. Whole families depended on the company. Sons followed fathers to sea in its ships. Perhaps more than anything else, this aspect of coastal life brought the realities of war at sea painfully home to the peaceful Gulf coast communities. Up to now they had felt relatively secure from the threat of the German submarine fleet. But with Caribou’s regularly scheduled run, crews no longer asked whether the U-boats might strike, but simply when.

The SS Caribou departed North Sydney on schedule at 7 pm that evening and exercised Life Boat Stations. Of the 237 persons aboard, scarcely a hundred would survive the crossing. Wartime conditions required the darkened ship to steer an evasive route. This evening she steamed at ten knots northward from Sydney towards Cape North before curving toward Port aux Basques with her single naval escort. U-69, commanded by 27-year-old Kapitänleutnant Ulrich Gräf, lay waiting.

Shortly before midnight local time, with relatively calm sea, very good visibility, and weak aurora borealis, Gräf sighted his target. He identified it as a large passenger freighter belching thick black smoke, followed by what he thought was a two-stack destroyer. He erred on both counts. The “destroyer” was a minesweeper, and the ferry was small. Both ships—Caribou and HMCS Grandmère—were running blind, for neither had radar.

SS Caribou was just 40 miles southwest of her destination at 2:21 am when the surfaced U-69 fired a single torpedo from a range of 650 metres. Forty-three seconds later the torpedo struck home, exploding the ship’s boilers. Her bottom torn out, the ferry sank in just four minutes. Shocked into wakefulness by the attack, and jolted from their bunks, passengers sought out family members under chaotic conditions before gaining access to the upper deck. Many became separated in the confusion. The submarine had dived, and could now hear the loud wracking noises of Caribou’s bulkheads breaking up as she sank to the bottom.

Meanwhile, scantily clad passengers scrambling along sloping decks, or in search of family members in the cabins below, had little time for reflection. Water was rushing into darkened cabins and passageways, passengers groped for lifebelts and hastened to safety. Some survivors reported the sheer terror, panic, and “indescribable chaos” before the ship went down. They told of passengers clutching for lifeboats and rafts, many of which had been shattered by the explosion; they spoke of a woman “in a frenzy of terror” who threw her baby overboard and then jumped after it to her death; they recounted the tale of 15-month-old Leonard Shiers of Halifax who was lost at sea three times—only to be saved each time by a different rescuer. He was the only one of fifteen children aboard to survive. In all, the situation was confused and desperate.

The swift destruction of the Caribou left survivors to a night of quiet desperation, debilitating hypothermia, and sometimes a lonely death. Exhausted and terrified as many were, the spiritual heritage of generations of seafaring Newfoundlanders gave them strength. Throughout the night one could hear praying and the singing of hymns. Clutching debris, an upturned boat, or huddled in overcrowded rafts for up to five hours, many survivors bore witness to selfless courage. Typical of this spirit was Nursing Sister Margaret Martha Brooke, RCNVR, of Ardath, Saskatchewan, who struggled all night long in the vain attempt to save her companion, Nursing Sister Agnes Wilkie, RCNVR, of Carmen and Winnipeg.

News of Caribou’s fate reached the Canadian public three days after the event. The Ottawa Journal proclaimed “Caribou Sinking Proves Hideousness of Nazi Warfare;” the Halifax Herald headlined “Women, Children among Victims as Torpedo Strikes.” It claimed the loss as the “Greatest Marine Disaster of War in Waters Fringing the Canadian Coast.” When the Caribou death-toll of 137 persons was finally established, the press could assert with little exaggeration that many families had been “wiped out.” Eye-witness accounts emphasized the viciousness of the attack; they highlighted the courage and stamina of those who survived, and the human dignity of those who succumbed. For the first time, Minister for the Navy Macdonald preached in a style he had not previously adopted: “The sinking of the SS Caribou brings the war to Canada with tragic emphasis. If anything were needed to prove the hideousness of Nazi warfare, surely this is it. Canada can never forget the SS Caribou.”

In 1945, Nursing Sister Brooke won the Order of the British Empire for her gallantry and courage on that fateful night. In 2015—when she was one-hundred years old—the navy named an arctic patrol vessel after her.

—adapted from U-Boats against Canada: German Submarines in Canadian Waters (1985)

Convoy to Tobruk

Osmond Borradaile (1898–1999) and Anita Borradaile Hadley (1938– )

The eight-month Siege of Tobruk, the strategically vital port on Libya’s eastern Mediterranean coast, was the scene of a number of running battles between Allied and Axis forces in World War II. Libya had begun the war as a colony of Italy, but as the Siege opened in 1941, had fallen under British control. Serving under special assignment with the British Army, Canadian cinematographer Osmond Borradaile was aboard the British minelayer HMS Latona proceeding from Alexandria to resupply the besieged port of Tobruk. En route, Latona and her convoy experienced a devastating attack by German aircraft. The state-of-the art Latona blew up and sank, thus ending her brief five-month career.

That evening I was enjoying a drink in the wardroom with some of the officers when action stations sounded. Grabbing my camera, I rushed onto the deck. A glaring sun hovered just above the horizon, and we were heading right into it. Planes suddenly appeared overhead out of the dazzling brightness. Once again we took evasive action. A low-flying plane, only fifty feet or so above the water, shot out of the sun and headed straight for us. The Latona swerved sharply as the aircraft dropped a torpedo and veered away. Just as I caught the plane in my camera finder, our pom-poms opened up right on target. A flash and cloud of smoke followed the steady thump of shells and the water below sprang to life as the disintegrating plane hit the surface.

The enemy attack slowed down sporadically, only to pick up again with added fury as reinforcements closed in. It was getting quite dark when a concentrated attack opened up on us. In the course of the ensuing action I think the Axis threw everything they possessed at us: torpedoes, bombs from both high-level and dive-bombing planes, flare after flare. All this together with our own guns made a spectacular display and provided me with enough light to get something really worthwhile. I had scarcely exposed three rolls when a heavy bomb landed by our four-inch gun turret. Knocked unconscious by the explosion, I saw no more of HMS Latona’s desperate fight for survival.

Eye-witness accounts allowed me to piece the story together. The bomb that had knocked me out had crippled the ship’s steering gear. Ablaze, she had become a sitting target. As the crew assembled on deck to abandon ship, two officers ordered batches of men to jump onto the deck of HMS Encounter as she passed close by. By the time the last group of men had jumped to safety, the section of the ship where they had been standing had become a mass of flames and the two officers were too late to make the jump themselves. They made their way to the stern to signal one of the destroyers to come back for them. A pile of land mines caught fire as they waited. The intense heat forced the decision to jump into the water and swim to the destroyer, when a body fell onto them from atop another stack of mines. Although badly burned, it seemed to move, and those two valiant officers decided not to desert it. Instead of leaping into the sea, they waited for HMS Encounter to make one final pass across the stern. Grabbing the unconscious bulk by the ankles and wrists, they tossed it to the passing deck before jumping to safety. I owe my life to those two brave men, for I was the dead weight they saved. Minutes later, the Latona blew up in a huge ball of flames and sank almost immediately, taking thirty-eight of our men with her.

I regained consciousness around midnight in the wardroom of HMS Encounter where the doctor was attending the wounded. I had second-degree burns from my neck up: my lips, ears, and scalp were crisp. These the doctor plastered with tannic acid jelly. But what grieved me more than my wounds was to learn that my cameras and negatives had gone down with the ship. Indeed, my precious Newman Sinclair camera must have acted as a shield, for it saved my face from severe lacerations. It possibly even saved my life.

—from Life Through a Lens: Memoirs of a Cinematographer (2001)

The Last Siege of Malta

Gordon W. Stead (1913–1995)

Many Canadians served with British forces during the two world wars. The seas on which they served shaped them as much as did the Forces with which they sailed. Whether going to sea in capital ships in the North Sea, motor torpedo boats in the Channel, or Fairmiles in the Mediterranean, their lives were irrevocably changed. Seafaring triggered self-reflection, and frequent meditation on human conflict and purpose. One such mariner was Gordon Stead, a naval reservist who fought in coastal craft in the Mediterranean against Germany and Italy at the height of the Siege of Malta. This was one of the most crucial theatres of war. Powered by two gasoline engines, the motor launches reached a top speed of 21 knots, but had a range of some 1,500 miles when cruising at 12 knots. They were floating “powder kegs,” for they carried 5,000 gallons of high-octane fuel.

In June of 1942, midway through the second year of the latest siege of Malta, one of the smallest ships to wear the proud White Ensign of the Royal Navy was at sea off the beleaguered isle, attended by a harbour craft. The sun was almost at its zenith in a cloudless sky, its glow rebounding from the serene blue water. In the near distance through the light haze loomed the pale gold margin of the land. No other vessels marred the even surface of the sea, and all that day no aircraft scarred the sky.

I was the captain of this little ship and this day stands out in my memory because it was so peaceful and because we were so alone. We—my ship, her crew, and I—were quite used to being alone at sea outside our fortress. Our striking forces had all been driven out to safer havens. But it was unnatural that we were not threatened from the air. Five days before, three front line German fighters had roared in upon us out of the sun and filled our wooden, petrol-driven vessel full of holes. For months the “blitz” had been continuous, and the rain of bombs had laid waste the dockyard and much of the surrounding built-up area. On this one day, although there were no friendly fighters anywhere nearby, we were left in peace.

The action was to westwards and to eastwards where two convoys fought to reach our Island a day’s sail away. While we prepared for their arrival at the focal point, the blitz descended on our approaching friends and left us be. Gerry had no time for us. Remnants of one convoy only made it into Malta, but that relief staved off surrender for lack of food and fuel. With the convoy there came also modest reinforcements. This was the turning point, although that could be no more than a premonition on that strangely tranquil day.

How came this small craft to be in this exposed position? How came I to be her captain? We were as far into this hostile sea as it was possible to get—a thousand miles from the nearest friendly base at either end—without starting to go out again. We had flouted this hostility to get here three months before, since when our larger colleagues all had left. We were now the very, very tip of British seapower in this historic sea. We would go on to continue as the leading edge of the naval thrust that cleared the Mediterranean …

While my own tale, it is as much the story of the ship, for I commanded her throughout her operational career and when I left she died—poignantly symbolic of the naval usage that a captain and his ship are one. Tossed by the winds of war, we, too, were like “a leaf upon the sea” an allusion reinforced by the maple leaf badge we wore upon our bridge front to assert that her commander was Canadian.

The context of this story is the most murderously destructive war that has yet been fought. More horrendous wars have been invented, but they have not so far been let loose upon the world.

However, my war differs from the current popular conception of a global conflict. It was not fought by people in front of radar screens pushing buttons to launch missiles at some target half a world away. Rather it was a deadly game of contact and manoeuvre and team play wherein one might see his adversary or at least his vehicle. Being personal, there was room for initiative and daring.

Moreover, my time was served at sea, and the sea imposes terms that are quite different from those permitted by the land. Mariners must first learn to live with every mood and hazard of a temperamental element. The menace of the enemy is just one more reason for being sharp. When the enemy appears, he comes in small packages—an aircraft or a ship—and the object of the exercise is to put the threatening package out of action. Once that is done, the people from the package become survivors to be rescued, since they no longer bear upon the outcome. For officers and crew, sea fights mean standing on an open bridge or manning armament or engines—it is the ship that does the running as though the adrenalin were flowing in her veins.

Scenarios like these mean lengthy periods of tension, sudden shocks of fear, and instants of high excitement—albeit tempered by the joys and challenges of being at sea—but they do not inflame the blood. There are no mass charges by wild hordes sticking bayonets into fellow humans. There can be pain and suffering, but no vast scenes of carnage. And, ordinarily, there is no call for hatred.

—from A Leaf Upon the Sea: A Small Ship in the Mediterranean, 1941–1943 (1988)

The Sea Is My Enemy

Hugh Garner (1913–1979)

During World War II—from 1939 to 1945—Canada’s navy had to draw on many young and inexperienced personnel. In response to the demands of war the naval force grew from four ships and some nineteen hundred personnel to over four hundred ships and ninety thousand personnel. Under such conditions, recruits unfamiliar with the ways of the sea—and who had perhaps never even seen it before— became professional seamen in astonishingly short order. They had to in order to survive. Wartime service in the Naval Reserve was a rite of passage. In Garner’s novel one such recruit sets off to sea in 1943 aboard a Flower Class corvette on his first tour of convoy duty across the Atlantic.

The pre-dawn air was chill with the wind which swept off the blue-glass ice shelf of Greenland a few hundred miles to the north-west, and the cold black sea was raised into sullen, turgid ridges, its fringe of white petit-point blown away with each gust of wind.

Ordinary Seaman Clark, nineteen years old, Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve, stepped quickly through the sliding door of the wheel-house, shutting it behind him, and stood in the darkness on the narrow platform staring out at the noisy, heaving sea. He looked up into the darkened sky, catching a glimpse now and again of a patch of star-studded heaven as it dipped and curtsied behind and between the wider ceiling of scudding clouds. The whole cosmos revolved around an axis formed by the jutting bow and fo’castlehead of the small ship, and the whistle of the wind through the struts and halyards accompanied the pirouette of the fading night.

As he stood still, fastening the top toggle of his woolen duffle coat against the wind, he became aware of the dark, dreadful loneliness of the sea. He was suddenly afraid, and he tuned his ears to the more familiar sounds of the ship and his fellows. From below him came the clatter of pans in the galley as the assistant cook, who had been baking his nightly batch of bread, cleaned up before his mate arrived to prepare breakfast. Up ahead the four-inch gun strained at its lashings with every rise and fall of the gun deck, and the shells clanked mournfully in their racks. There was the sound of feet being stamped on the boards above his head as the port look-out changed his position on the wing of the bridge. The noises from aft were swept away with the wind.

The sounds of the ship only accentuated the noisy quietude of the limitless expanse of the sea, so that the boy shivered, and his hands gripped the railing beside him. Suddenly he was afraid of losing his grip on this heaving thing which was his only connection with security, and he feared to be cast away into the sea which hissed and foamed as it reached with white-nailed fingers upon the free-board below.

Standing there he realized that the sea cannot be loved; it is an enemy upon which men sail their puny craft—an alien thing armed with a multitude of claws ready to pull them beneath it with scarcely a ripple or a trace. It is too vast and too black and too uncomprehending to be loved. It gives neither succor nor hope nor life to those who must depend upon it. It is beautiful and terrifying, and gigantic and insatiable; a desert of water over which men travel through necessity.

He no longer thought of submarines and torpedoes, for now his fears were those which have followed men from the dawn of time; the primeval fears of the elements: of wind, of lightning, of the sea.

He strained his eyes aft to try to catch a glimpse of the look-out on the ack-ack platform; to find another human being with whom to share his terror; but the man could not be seen; he was alone. He fought with himself against the dread which rose through his fibres like a scream. With a desperate urgency he stumbled down the steep steps of the ladder, his heavy coat buckling around his thighs and his hands sliding down the wet railings, not allowing himself to look at the water, his eyes fixed on the swiftly falling stern of the ship. Half-way to the bottom his rubber sea-boot slipped from the serrated step, and his hands lost their grip upon the rails. With a soft thud, and an imperceptible swoosh of clothing, he fell the remainder of the way to the steel deck, and lay there, one arm doubled behind him, and his terrified eyes hidden behind their curtained lids. To his unhearing ears came the slap of the stoical sea as the tips of its tentacles caressed him through the drains along the scuppers.

—from Storm Below (1949)

A Memory of the Merchant Marine

Alan Easton (1902–2001)

Having served in both the Merchant Marine and the wartime Canadian navy, Alan Easton well knew the character of seafarers and the challenges they faced. From his own perspective of having commanded warships throughout the Battle of the Atlantic (1939–1945) he ponders the courage of those seamen who manned the cumbersome, often unarmed merchant ships that he had escorted across enemy-infested seas.

I finished this voyage with the sober realization that it was the merchant seamen who took the real onslaught of the enemy at sea. Their ships could hardly fight back against the elusive submarine and, due to their ponderous bulk, could not manoeuvre quickly to avoid their attacker. They always presented the best targets.

The men who lived in these ships could not have been unaware of their vulnerability. They pushed their ships along, never knowing when they would be singled out for extinction. In convoy they had little knowledge of how the enemy was deployed, and not much more when travelling alone. They lived, as it were, on the edge of a volcano. The constant suspense must have been awful.

These men may have tramped from Cape Town to Rio alone and unprotected save for an old heavy gun, crossing an ocean where powerful German surface raiders roamed. Up the Brazilian coast and through the Indies, still alone, to North America, where soon there was to be such devastation that upwards of a hundred ships (half a million tons) a month would be lost. Then in convoy across their familiar Western Ocean where their lives were in constant jeopardy, not only from the enemy but from the perils of the sea. On the coasts of the United Kingdom they would be haunted by torpedo-firing E-boats and hidden mines, and hunted by the bombers of the Luftwaffe who might well bring to an abrupt end, under the very lee of their home port, their ten thousand mile voyage.

In the semi-silence of war few people knew of the colossal tasks these unsung, un-uniformed and unnoticed heroes achieved. If any became known, too often they were overshadowed by the epics of the fighting men who had done no more and probably less. None but their families really knew how dangerous were their missions. If they came home—which 30,000 British merchant sailors failed to do—they soon had to turn again and face the same onerous conditions.

We who served under the White Ensign did not go through the torments they went through, nor did the other fighting services. A merchant seaman could fortify himself with nothing but hope and courage. Most of them must have been very afraid, not for days and nights but for months and years. Who is the greater hero, the man who performs great deeds by swift action against odds which he hardly has time to recognize or greatly fear, or the man who lives for long periods in constant, nagging fear of death, yet has the fortitude and endurance to face it indefinitely and carry on?

There was a motto in my old boyhood training ship: “Quit ye like men, be strong.” It may have helped those who had been weaned to the sea by this foster mother and who could still remember it.

—from 50 North: An Atlantic Battleground (1963)

Finale

George Whalley (1915–1983)

Narratives about war at sea often indulge in a kind of romanticism untenable on land. For in land wars, the debris of mortal combat scars the earth. Not so at sea where the bloody battles between ships on the high seas leaves neither trace of carnage nor sites for national shrines. George Whalley’s poem “Battle Pattern,” of which this excerpt forms part of the seventh and final canto, puts the lie to that notion. Written to mark the sinking of Germany’s battleship Bismarck by Allied forces on 27 May 1941, the poem is marked by its realism and mythic dimension. This reflects Whalley’s own experience of war at sea as a Canadian naval reserve officer.

There is not elegy enough in all

the winds and waves of the world to sing the ships,

to sing the seamen to their rest, down

through the slow shimmering drift of crepuscule,

sinking through emerald green, through opal dimness

to darkness. Not all laving of all the world’s

oceans, loving moonwash of warm

tropic seas can ever heal the hearts

smashed to fragments of desolated darkness.

Sink now, life ended, down through the haunts

of trumpetfish and shark and spermwhale, down

to the still siltless floor of the ocean where

no light sifts or spills through the liquid drifting

of darkness, where no eye sees the delicate

dark-wrought flowers that open to no moon.

—from The Collected Poems of George Whalley (1986)