The experiences on the Western Front during World War I had a strong influence (both negative and positive) on post-war defence doctrine. The positive aspect of World War I to the Germans, from the doctrinal standpoint, was the development of what is informally known as the ‘elastic defence’ (elastische Kampfverfahren, literally ‘elastic battle procedures’). By 1916 it had been realised that solid multi-layered trench systems and an unyielding defence, aimed at holding on to every metre of ground, were impractical. Massive six-day artillery barrages would shatter defences and the defenders. General of Infantry Erich Ludendorff endorsed a more in-depth defence. While still relying on continuous interconnected trench lines, the defences were subdivided into three zones: (1) combat outpost zone with minimal lookouts to warn of attacks and keep patrols from penetrating deeper; (2) 1,500–3,000m-deep main battle zone with complex trench systems concentrated on key terrain (rather than rigid lines covering all areas) intended to halt the attack; and (3) rear zone with artillery and reserves. While the battle zone still relied on trench lines, to establish the new defences the Germans actually withdrew (previously unheard of) in some sectors to more easily defended terrain, placed many of the trenches on reverse slopes to mask them from enemy observation and fire, and established strongpoints on key terrain. The establishment of the combat zone, supported by long-range artillery, disrupted Allied attacks. After fighting its way through the outpost zone the attack would often exhaust itself in the battle zone. Rather than attempting to halt the attack outright, penetration of the battle zone was accepted. The attack would become bogged down among the defences, battered by artillery fire and counter-attacks. This was first implemented in April 1917, and by war’s end in November 1918 the defences were completely rearranged under this concept. It had proved itself, and was adopted by the post-war Reichsheer in 1921.

In spite of the much-vaunted blitzkrieg concept of mobile warfare, in 1940 only 10 per cent of the German Army’s 138 divisions were motorised. The infantry division’s 27 rifle companies walked, and most artillery and supply transport were horse drawn. The lack of mechanisation had a major impact on how the Germans conducted defensive operations.

There were negative influences too of the experiences on the Western Front. The horror, misery and prolonged stalemate of trench or positional warfare (Stellungskrieg) encouraged many, like Hans von Seeckt, to find another way to wage war. Some form of mobile offensive was preferred and defence was regarded as necessary only for local holding actions or a temporary situation until the initiative was regained and the offensive resumed.

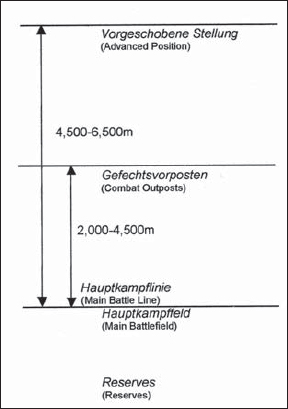

The elastic defence was codified in the two-volume manual called Führung und Gefecht der verbundenen Waffen (Leadership and Combat of the Combined Arms), published in 1921/23. This codification managed a compromise between those who still favoured the elastic defence (the old ‘trench school’) and those espousing a more mobile form of warfare. The manual stated that either form of warfare could be employed depending on the situation, but it clearly preferred the elastic defence, with improvements. These entailed more depth (both within each zone and in the distances between zones), and in fluid situations it called for a fourth zone forward of the three traditional ones. This was an ‘advanced position’ of light mobile units, infantry and artillery, which would disrupt the attack and force the enemy to deploy early into battle formation. The advance units would then withdraw and constitute part of the reserve. Anti-armour defence was addressed, but there were few effective anti-armour weapons at the time, being prohibited for the Reichsheer. This took the form of artillery concentrations and obstacles. The combat outpost zone would consist only of individual and infantry weapon positions not connected by trenches.

Such was the theory. In practice, Colonel General Hans von Seeckt, acting chief of staff, strongly discouraged any officer (with some being relieved of duty) from practising the elastic defence. Seeckt desired a mobile war of manoeuvre and shunned defence. Though Seeckt resigned in 1926, his successors continued to abide by his views, which remained in effect until the early 1930s. The practice of the elastic defence was permitted in exercises though. The rearmament of Germany in 1933 gradually saw the means become available to practise a highly evolved form of mobile warfare. This was by no means Army-wide, as the new deutschen Heer was still largely an infantry force relying on horse artillery and horse-drawn supply columns (4,000–6,000 horses per division). The infantry division’s 27 rifle companies may have walked, but the division did possess a degree of mechanisation via truck transport for headquarters, signal, anti-armour and pioneer elements. Divisional reconnaissance battalions too were increasingly mechanised, receiving motorcycles and scout cars, though horses and bicycles were still relied on.

The new defence doctrine, laid out in Truppenführung (Troop Command) in 1933, allowed the four previous zones a greater use of anti-armour obstacles, minefields, anti-armour guns behind the main battle position, and tanks assembled in the rear zone to support counter-attacks. The use of armour as a mobile counter-attack and manoeuvre force was not fully appreciated at this time though, as German tanks had played no role in defeating Allied tank breakthroughs in World War I. They would be held in the rear to engage enemy tanks that had broken through and to destroy them piecemeal as they wandered through the rear zone. There was disagreement on the employment of anti-armour guns. While some might be attached to the advanced-position forces, most were to be positioned behind the main battle position to block tank breakthroughs. Others urged that they be positioned forward to pick off approaching enemy armour and break up the attack early. Individual infantrymen were to attack roaming tanks with anti-armour rifles and hand mines, which proved to be inadequate. As the blitzkrieg (‘lightning war’) concept developed, the German Army became so offensively orientated that anything appearing too defensive in nature was at risk of being minimised. (Anti-armour gun Panzerabwehr units were redesignated armour-hunting Panzerjäger units on 1 April 1940: anti-armour guns were still called Panzerabwehrkanone or Pak. for short.)

The German ‘elastic defence’ concept.

In the first two years of World War II German defensive doctrine was of secondary importance. Units did of course assume defensive postures locally as the operational situation required. General defensive situations for large formations were for the most part unnecessary. While units developed coastal defences, and the Afrikakorps was forced on the defensive at times, there was no major test of Germany’s World War I elastic defence legacy. This would change in the winter of 1941. The broad expanses of the USSR, the necessity of defending on wide fronts, the decline in manpower, the loss of critical weapons and equipment, the massing of Soviet infantry, armour and artillery, and the terrain and weather themselves forced revisions in defensive doctrine. Other theatres of war, particularly North Africa and Italy, demanded additional changes and considerations. Eventually, soldiers fighting on different fronts would employ unique defensive tactics and adapt their fighting positions to local conditions.

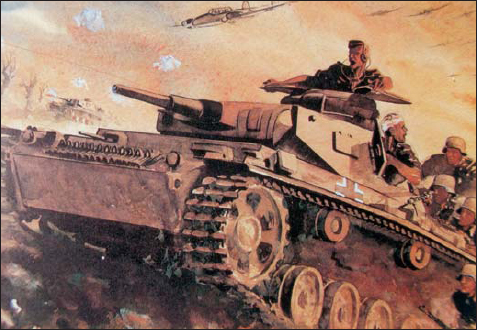

The Eastern Front, 1942: a Panzer III, supported by Bf 110s, pushes into the Soviet Union. From early-1943 the Panzerwaffe no longer spearheaded the German Army, but largely acted as a mobile reserve to support the relied-on German defensive positions. (E. Gross)

Regardless of the unique aspects of any given front, at all unit levels (defined by the Germans as regimental level and below) common principles for the establishment and conduct of defence were employed down to the squad. Space, distances, density of forces, and support would vary though, as would construction materials, types of fortifications, obstacles, and how they were deployed and manned.

Field fortifications were necessary during offensive movements too. Here infantrymen dig in for the night on a Russian steppe to provide protection to 7.5cm StuG III Ausf. F assault guns. These would be shallow slit trenches more suited to the role of a soldier’s bed than a fighting position.

High ground was always desirable for defensive positions for its observation advantages, extended fields of fire, and the fact that it is harder to fight uphill. In the desert even an elevation of a couple of metres would be an advantage. Natural terrain obstacles were integrated into the defence as much as possible. The routes and directions of possible enemy attacks were determined and infantry and supporting weapons were designated to cover these approaches. The goal was to destroy or disrupt the attackers by concentrating all available weapons before the enemy reached the main battle position. Effective employment of the different weapons organic to an infantry regiment was an art in itself, as each had capabilities and limitations: the weapons comprised light and heavy machine guns, anti-armour rifles, mortars, infantry guns, anti-armour guns, and supporting artillery to include anti-aircraft guns employed in a ground role.

A commander preparing a defence (and an attack) needed to identify the main effort point (Schwerpunkt). In attack, this was the point at which he would concentrate effort and firepower to break through the enemy defences. In defence, this was the point (assessed by the defending commander) where the enemy would attempt to break through: he would concentrate his defences and supporting weapons there. The defence would be established in depth, but not just using the four zones: each zone in itself would be organised in depth with the weapons providing mutual cover for each other. The employment of obstacles and minefields was critical, as it was fully understood that anti-armour weapons alone could not halt attacking tanks. Tank-hunting detachments with anti-armour rifles and hand mines were organised. In 1943 Panzerfaust and Panzerschreck shoulder-fired anti-armour rocket launchers began to replace these.

As the war progressed, anti-armour guns were increasingly employed in the main battle positions as well as in forward and outpost positions. Armoured fighting vehicles (AFVs – tanks and assault guns) tended to be held as mobile reserves to counter-attack breakthroughs. There were many instances though where AFVs were employed as mobile pillboxes. As Germany lost ever more AFVs and infantry units were reduced in strength, the availability of mobile reserves dwindled. Rather than large units conducting major counter-attacks, they became increasingly localised and smaller, greatly reducing the German ability to regain lost ground.

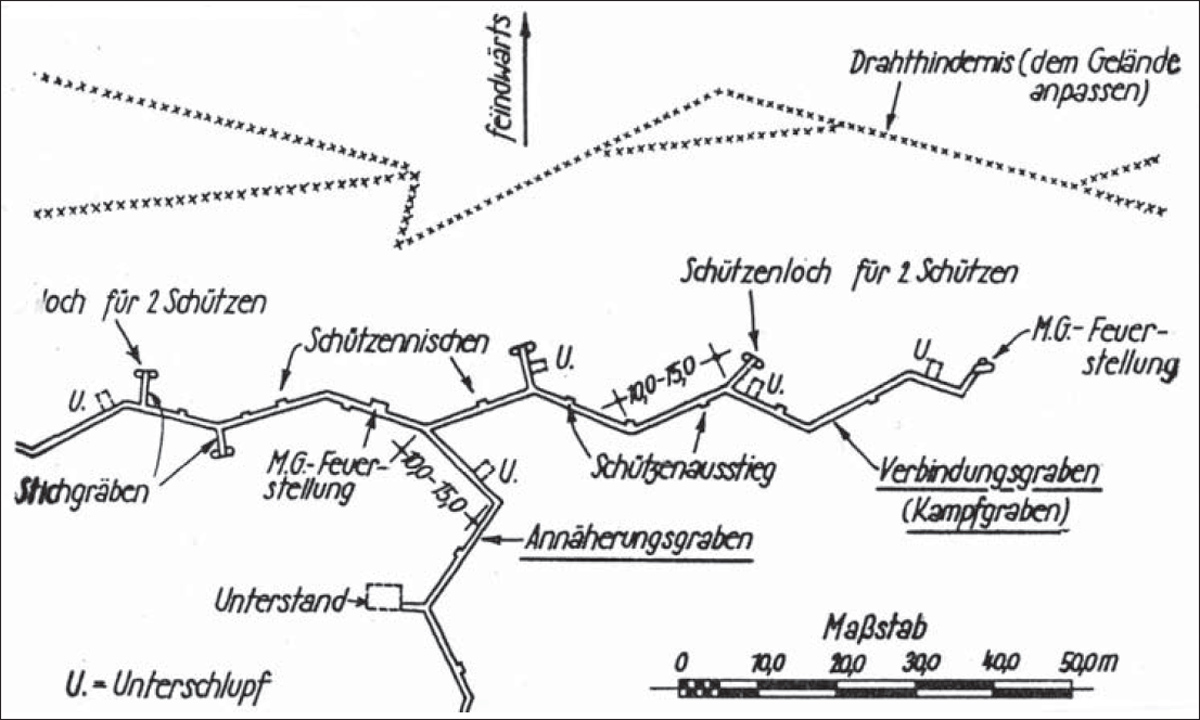

This squad battle trench (Kampfgraben) and approach trench (Annäherungsgraben) depicts the different positions incorporated into it: Schützenloch für 2 Schützen (rifle position for 2 riflemen), Stichgräben (slit trench), Schützennischen (fire steps), M.G.-Feuerstellung (machine-gun firing position), Unterstand (squad bunker), Schützenausstieg (exit ladder or steps), Unterschlupf (dugout). Note that the feindwärts arrow points in the direction of the enemy.

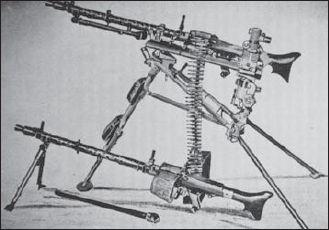

The 7.92mm MG.34 machine gun in the light and the heavy roles provided the weapon on which small unit defence tactics were centred. Maximum effective range of the MG.34 and the later MG.42 in the light role was 1,200m, although it was common to engage targets at much closer ranges. In the tripod-mounted heavy role, its range was 2,000m.

Because of the extensive defensive frontages often required, ‘strongpoint’ defence was adopted on many fronts: there were no continuous frontlines. The gaps between mutually supporting strongpoints were extensive, to be covered by outposts, patrols and observation, backed up by long-range fire. This reduced the numbers of troops necessary to defend an area, but not necessarily the number of weapons. Strongpoints had to be well armed with the full range of weapons. Strong mobile reserves were a necessity. Still, the basic German doctrine of four defensive zones was retained to provide depth to the defence.

Camouflage efforts and all-round local security were continuous during the development of defensive positions. Camouflage had to prevent the enemy from detecting positions from the ground and the air. Reconnaissance forward of the defensive zones was essential to warn of the enemy’s approach and his activities. The Germans developed a good capability of determining when and where the enemy might attack by closely watching for signs of offensive action.

A wide variety of anti-personnel and anti-armour obstacles were employed. Maximum use was made of local and impounded materials. While it was difficult to conceal obstacles, the Germans would emplace barbed-wire barriers along natural contour lines, on low ground, on reverse slopes (Hinterhang), along the edge of fields and within vegetation. Terrain was important: swamps, marshes, forests, rivers, streams, gullies, ravines, broken and extremely rocky ground, all halted or slowed tanks. They fully understood that to be effective an obstacle had to be covered both by observation and fire.

Obstacles

| Hindernis | Obstacle |

| Astverhau | branch entanglement – tree or branch barrier |

| Baumstämmen | abatis – interlocked felled trees |

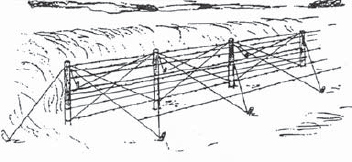

| Flanderzaun | ‘Flandrian fence’ (pictured, below left) – double-apron barbed-wire, fence |

| Hindernisschlagpfahl | barbed-wire picket post |

| ‘K’/‘S’ Rolle | concertina wire – coiled spring, steel wire; ‘K’= plain wire, ‘S’= barbed wire |

| Koppelzäune | cattle fence – 4 or 5-strand barbed-wire fence |

| Panzerabwehrgraben | anti-armour ditch |

| Panzersperre aus Baumstämmen | armour barrier of [vertical] tree trunks |

| Pfahlsperre | stake barrier – featuring timber, log, or concrete posts |

| Schienensperre | rail barrier – vertically buried train rails |

| spanischer reiter | Spanish rider – portable wooden frame barrier wrapped in barbed wire (a.k.a. knife-rest, chevaux de fries) |

| Stacheldraht | barbed wire |

| Stahligeln | steel ‘hedgehog’ obstacle – three crossed girders |

| Straßensperre | roadblock – a general term |

| Stolperdranht-hindernis | trip-wire obstacle – low entangling wire |