To examine the conduct of a doctrinal early-war defence, the battalion level is the most useful to look at. The deployment of the companies and platoons, the key defensive subunits, and the allocation and employment of battalion and regimental support weapons can be best scrutinised at this level. The later strongpoint defence and other methods of defending were simply modifications of this basic doctrine. The Germans viewed battalions as the building block of a formation’s combat power. Regardless of how a unit was organised or what its reduced actual strength was, the number of battalions a division was able to field determined how it would be organised for combat and fight.

A battalion deployed two companies forward on its 800–2,000m front on defendable terrain with good fields of observation and fire. The third company was 100–300m to the rear, preferably too on defendable terrain, but also in a position from which to conduct an immediate counter-attack (Gegenstoss) in the event that the forward companies were pushed back. If the forward positions were penetrated and still partially intact, then the reserve company would serve as a blocking force (Sperrverband) to halt enemy penetrations or by manoeuvering into another position. The reserve company could also be manoeuvred to protect a flank if an adjacent battalion was penetrated or forced to withdraw.

A variety of support facilities were established in the battalion and company areas: command posts, ammunition points, medical aid posts, telephone exchanges, artillery observation posts, truck and wagon parks, and kitchen trailer positions.

Rifle platoons were positioned with their squads in relatively close proximity with narrow gaps between them; this was called a platoon point (Zugspitze). Three-squad platoons usually had all three squads on-line while four-squad platoons usually placed one to the rear covering the forward squads. In effect, each platoon position was a strongpoint and ideally would be partly surrounded by barbed wire and mines. Gaps between platoons and companies were wider, but covered by patrols, fire, and, if time and resources allowed, mines. Some rifleman and machine-gun positions might be located outside the immediate platoon perimeter to cover gaps and approaches that could not be covered from within the position.

The shadowy figure of a sentry stands guard over a canvas-wrapped machine-gun post. The position has been revetted with hay bails. Even though they were open-topped, these bails helped insulate the position.

Each company deployed its reserve platoon several hundred metres forward in a widely scattered line across the company’s sector. These were simple, hastily built positions serving to prevent surprise attacks, keep enemy patrols at bay, send out their own patrols, and warn of the enemy’s approach. The outpost positions were sometimes situated to make the enemy believe that this was a mainline or to mislead him into thinking the mainline was in a different direction. They would not attempt to conduct a stout resistance, but engage the enemy at long range and withdraw by concealed routes to the reserve position, which (if time allowed) had been prepared in advance.

It was found that artillery barrages and engineers easily penetrated continuous minefield belts laid across the front. Though dense mine belts were still employed on the Eastern Front and in North Africa, it was more effective to lay them within the main battle positions and at key points on roads, such as intersections and blockage points where off-road movement was restricted.

Field telephone lines were run down to platoon command posts and heavily relied on for communications. Radios were little used within battalions. Telephone lines were laid down gullies and roadside ditches, and time permitting, buried, to protect them from artillery and tracked vehicles. Messengers and signal pistols with coloured flares and smoke cartridges were also important means of communications.

The normal allocation of support weapons saw the regiment’s two light infantry gun platoons each attached to a forward battalion; the heavy platoon remained under regimental control. The four regimental anti-armour company platoons gave the commander a great deal of flexibility: two platoons each to the two forward battalions, one platoon per forward battalion and two in reserve, one platoon per battalion with the fourth in the combat outpost position or protecting a flank are just some examples. With a platoon attached to a battalion usually two guns were detailed to each of its forward companies, but they may have been positioned behind the forward platoons. Alternate positions were prepared for each gun. Anti-armour weapons were often sited to enable them to engage tanks from the flank. The battalion machine-gun company’s three platoons could be attached to each rifle company, or rather than one being attached to the reserve company, it could be under battalion control to secure a flank or in the combat outpost position. In forests and urban areas the heavy machine guns were often employed as light guns and deployed well forward with the rifle platoons to augment their close-range fire. Alternate positions were prepared for most machine guns. The mortar platoon’s six mortars were usually retained under battalion control, but a mortar squad (two mortars) or a single mortar could be attached to each rifle company, which was the case with the strongpoint defence. The rifle company’s three anti-armour rifles could be attached to each rifle platoon or grouped together as one element for volley fire against tanks.

The positioning of anti-armour guns and the sectors of fire they covered was based on the assessment of terrain over which enemy AFVs could approach. Terrain was classified as armour-proof (Panzerschier) – impassable to AFVs; armour-risk (Panzergefährdet) – difficult for tanks; or armour-feasible (Panzermöglich) – passable to armour. This determination was made by map and ground reconnaissance. Panzerschier terrain included dense forests, swamps, marshes, deep mud, numerous large rocks and gullies, steep slopes, railroad embankments or cuts, etc. Infantry on the other hand might attack across such ground requiring it to be covered by machine guns and mortars.

Infantry battalion defence sector

A full-strength infantry battalion normally deployed for defence with two companies forward on its 800–2,000m front. The positions of the heavy machine guns and mortars of the battalion machine-gun company (4th) are depicted along with the four 3.7cm anti-armour guns and two 7.5cm infantry guns attached from the regiment. Each platoon position (Zugspitze) contains three light machine guns and a 5cm mortar. Medical posts and ammunition points are located near each company command post. In this instance the 1st Company on the left has two platoons (1/1 and 2/1) deployed on the main battle line (Hauptkampflinie) with the 3rd Platoon (3/1) in outposts (Vorposten). It would withdraw to a reserve position behind 1/1 and 2/1 blocking the main road through the company sector. The 2nd Company on the right has its 3rd Platoon (3/2) also in an outpost position. It, however, would withdraw to a position on key terrain forward of 1/2 and 2/2. When forced to withdraw from that position it would occupy a reverse slope reserve position behind 1/2 and 2/2. The 3rd Company is positioned as the battalion reserve across the rear area. It can remain in position to block a breakthrough or conduct counter-attacks. The regimental boundary is shown by the ‘III’ line; the battalion boundary by the ‘II’ line; and the company boundary by the ‘I’ line. Contour lines for the terrain are also provided.

Weapons engaged the enemy at much closer ranges than their maximum effective ranges. Some anti-armour guns would open fire at ranges up to 1,000m, but most would hold their fire until 150–300m. Anti-armour rifles engaged at the same range. Heavy infantry guns and mortars fired smoke rounds approximately one-third of the way back from the front of the attacking formation’s lead tanks. This blinded the following vehicles, but did not screen the lead tanks from anti-armour gunners. The Panzerfaust had only 30, 60, and 100m ranges depending on the model, but tanks were engaged at much closer ranges to ensure a hit. The Panzerschreck usually engaged within 100m. Mortar and infantry gun concentrations were planned in front of and to the flanks of platoon and company positions, in the gaps between positions, in areas from which the enemy might attack, and in locations where he might emplace his own mortars. The infantry guns, possessing longer range than mortars, would be assigned deeper targets.

Early doctrine called for large-scale counter-attacks to be organised and launched, but this gave the enemy valuable time to consolidate on the objective and prepare to beat off the attack. Instead, counter-attacks were to be conducted as soon as possible on penetrating enemy forces in order to keep them off balance and delay their consolidating on the objective. Any unit in position launched squad or platoon attacks, rather than waiting for larger counter-attacks to be organised.

An Afrikakorps soldier attempts to create a hole in the crusty chalk gravel on a coastal plain. Blasting was often required, and piled rocks were used for cover.

In September 1942 Rommel’s offensive ground to a halt at Alam Halfa against stiff Commonwealth resistance. Having lost large numbers of AFVs and short of fuel, he chose to establish a strong defensive line rather than withdraw and lose the territory he had gained at great cost. He possessed sufficient mobile forces to halt British attacks with immediate counter-attacks. He did not possess enough for the mobile defence he preferred, and so would have to rely on a static, in-depth infantry defence.

A 61km-long defence zone was established from the coast 4km west of El Alamein south to the deep Qattara Depression providing a protected flank. The terrain was mostly flat, stoney desert with a few scattered ridges that became key positions. Some barbed wire was used, but the Germans relied on deeper, denser minefields than previously used. Existing British minefields were integrated into the German’s two main belts, Minefields I and H, the ‘Devil’s Gardens’ (Teufelergarten). Of the 445,000 mines laid, only three per cent were anti-personnel, lessening the danger to sappers breaching the fields.

Small observation and listening posts were established beyond the minefields to prevent infiltration by patrols. Within the western portion of Minefield I each infantry battalion positioned a company in the combat outpost line. Withdrawal lanes were provided through the fields. This zone was much thinner than normal and the British noted it during the offensive, having expected more resistance during the penetration of this area. The battalions’ other two companies were in the main battle line with the bulk of the 800 anti-armour guns 1,000–2,000m behind the combat outposts and protected by Minefield H. The mine belts were compartmented and connected by traversing mine belts. With six weeks to prepare, the infantry defences were well developed and adequately protected from the near World War I-intensity artillery barrages. Some German units were mixed among the Italians in the line rather than placing the worse led and poorly armed units in their own sectors. The Italians provided the bulk of the infantry though with five infantry divisions in the line and only one German. This occurred too in the mobile reserve with a Panzer division paired with an Italian mobile division. The mobile reserves were positioned 1–3km behind the main battle line. This placed them within range of British artillery, countered by wide dispersal and digging in, but ensured their deployment rather than moving forward to counter-attack under air attack. A German and an Italian motorised infantry division were positioned astride the coastal highway 5–8km behind the front.

The Eighth Army attacked on the night of 23 October supported by massive artillery and air support. Sappers, after much effort, breached the minefields in the north. A supporting armour attack in the centre was repulsed, as was a larger attack in the south on the 25th. The British, with twice as many tanks as the Germans and Italians, broke out on 4 November. It had taken the much superior Commonwealth forces 12 days of intense close combat to break through a 3km-deep defence belt. Rommel, short of fuel and ammunition, having lost much of his armour, artillery and many anti-armour guns, successfully withdrew west as the British became bogged down in torrential rains.

The Germans were adept at defending towns and those in Italy were especially suitable for defence, with their heavily constructed stone and concrete multistorey buildings with cellars. Combat in built-up areas was costly to both the defender and attacker. The Germans made the seizure of towns as punishing as possible for the Allies and took advantage of the cover and concealment towns provided from artillery and air and the time it bought. Ortona was to be the first town in which the Germans conducted a major defensive and delaying effort.

To the Germans a town was a ready-built strongpoint and a deathtrap for enemy tanks. The main defence line was located well within the town to deny the enemy observation and direct artillery and tank fire on the defences. Outposts and observation posts were placed on the town’s edge with others well outside the town to observe avenues of approach. Mines and other obstacles blocked roads, bridges were demolished, and mines and anti-armour ditches were emplaced across fields through which tanks could approach. Hills, clumps of woods, and groups of buildings outside the town might be defended as all-round strongpoints or at least combat outposts to deny or delay the enemy use of them or to prevent the town from being enveloped.

Troops of the 85th Infantry Division search a fairly well-camouflaged German machine-gun position on Mt Altuzzo, Italy, in September 1944. A dugout is located at the position’s right end. Two MG.42 machine guns were located in the position, providing a broad field of fire. Also in the position is a Torn.Fu.d2 radio indicating it may have doubled as an artillery observation post.

The main defence line was laid out in an irregular pattern to make it more difficult to locate, and prevent outflanking if penetrated. Particularly strong or dominating buildings were fortified as strongpoints on the main roads through the town. Snipers, anti-armour teams with Panzerfausts, and machine gunners were positioned in other buildings as well as placed forward of the main defence line along with small strongpoints. These disorganised the attackers before they reached the main defences. Secondary lines were prepared along with switch lines to contain penetrations. Even if a defended town was incorporated into a main defence line, it was prepared for all-round defence in case the external lines were penetrated and the town encircled. Reserves were positioned well inside the town in stout buildings while others might be held outside the town.

Streets could be blocked with roadblocks built of rubble, wrecked vehicles and streetcars, and heavy logs buried vertically. These log walls could be formidable obstacles up to 3–4m high and braced with angled logs, though these were more common in Germany. Rivers, streams and canals passing through towns were incorporated into the defence plan. Sometimes buildings were blown into streets blocking them with rubble. Mines were also used. Some streets were left unblocked to allow enemy tanks to move into close-range ambushes or tank-trapping cul-de-sacs. Side streets were sometimes blocked to prevent tanks from turning off when engaged. These roadblocks were recessed back into side streets to prevent their detection until passed. Town squares and traffic circles were set up as killing zones.

Buildings were booby-trapped and in some cases prepared with demolitions, to be detonated when the enemy occupied them. Doors and ground-floor windows were blocked with rubble and furniture, as were alleys. Other windows were left uncovered and open so that the enemy could not determine which windows were being fired from. Loopholes were knocked through walls and roof tiles and shingles removed. Many of these were unused, serving only to mislead the enemy. Positions were set up using chimneys for cover. Lookouts and artillery observers did use church belfries as posts, but once the enemy closed on the town they would evacuate them, as they were obvious targets. Snipers avoided them, despite what is often depicted in motion pictures. Attackers moved down streets hugging building walls. Defending riflemen and machine gunners took up positions on both sides of a street to cover the opposite side. Residences were mostly constructed as adjoining rows of houses. ‘Mouse-holes’ (Mauseloch) were knocked through interior walls to connect the buildings on different floors including cellars. Doors sometimes connected the cellars of buildings on the same block. This allowed troops to reposition or reinforce. They were also used to reoccupy buildings that had been cleared by the enemy. Mouse-holes were sometimes concealed by furniture. Storm sewers were also used for movement between positions. Anti-armour and machine guns were positioned in cellars and other machine guns mounted in upper windows. Tanks had limited gun elevation and could not engage higher floor firing positions. Rubble piles had firing positions hidden in them. Panzerfausts were fired from alleys and other hidden sites in the open as they could not be fired from within buildings. Tanks and assault guns were concealed in buildings to fire down streets.

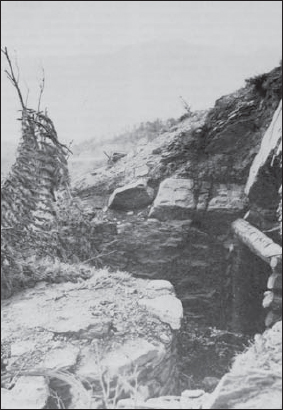

A log-reinforced dugout and rock-revetted fighting position on Mt Altuzzo, Italy, September 1944. This directed fire onto the forward slopes and across the La Rocca draw, which was an approach route. A camouflage net garnished with pine branches has been pulled away to reveal the position.

Ortona is on Italy’s east-central coast opposite Rome and was the eastern anchor of the Gustav Line. The 10,000-population town was on level ground with the outskirts open, offering little cover. There were no natural terrain features to aid the defence. It had been hoped that the Germans would abandon the town and defend further north. The northern old town had narrow, twisting streets, large squares, and the buildings were more heavily constructed. The newer southern portion had wide straight streets. The buildings were stone and masonry with many 3–5 stories.

The Canadian Army experienced a tough fight on the southern approaches to Ortona. Two reinforced German paratrooper battalions defended the town covering a 500m x 1,500m area. The Germans defended in-depth using most of the tactics and techniques discussed previously. Intentionally blown-down buildings blocked most of the streets leaving only one main thoroughfare through the town’s south-to-north axis, which chanelled the Canadian tanks into killing zones.

One extremely effective technique used to defend street intersections bounded by multi-storey buildings was to use demolitions to blow up the corner portions of the building on the enemy side. This exposed the interiors of the buildings across from the German-defended buildings. They might destroy a corner of one of their own buildings and use the rubble to barricade the street on the German side behind which were machine gunners and riflemen. They would withdraw when the attacker’s fire became too intense. As the attackers crossed over the barricade machine guns sited in second- and third-storey windows further back down the street opened fire. An anti-armour gun might be positioned behind a barricade down the side street to engage any tanks that might approach the barricade as it crossed the street. Large demolition charges were emplaced in some buildings and command-detonated when occupied by the Canadians. Many houses were booby-trapped as were rubble piles used as cover by the attackers. Mines were hidden in barricades that tanks might try and crash through. In the north part of Ortona defence lines were established along the broad squares and separate buildings were demolished to deny cover to the attackers and provide wider fields of fire.

The Canadians launched their attack on 21 December 1943. The Germans were gradually pushed back through the town, falling back on successive strongpoints. Both defender’s and attacker’s tactics and techniques evolved through the battle with the Germans constantly introducing new methods. On the night of the 28th/29th the Germans withdrew after causing a nine-day delay to the Allied approach to the Gustav Line. Ortona was knicknamed ‘Little Stalingrad’ by the Canadians. They took over 2,300 casualties in Ortona plus larger numbers suffering from combat fatigue, and the 1st Canadian Division was temporarily combat ineffective.

The extreme north flank of the Eastern Front rested on the Barents Sea in an area where the borders of Norway, Finland and the USSR touched. In September 1944, after a major Soviet offensive mauled the Finnish Army (allied with Germany) in the south, Finland signed an armistice. It required that Finland expel or disarm German forces in the country, most of which were north of the Arctic Circle. The Germans soon began withdrawing to Norway. Units remained on the extreme north flank though to protect this withdrawal, as they could not move through Sweden. Not satisfied with the pace, the Soviets attacked in early October.

In the area of operations the north-eastward-flowing Titovka River defined the Finnish-Soviet border. German positions were as much as 12km inside the USSR on a strongpoint line (Stutzpunktlinie) known as the Litsa Front (after the river it was anchored on). The narrow coastal plain is covered with tundra and low rock hills with scores of rivers and streams flowing into the sea. Inland the terrain is barren, featuring rock hills and ridges up to 580m above sea level with scattered low brush and scrub trees. The many streams, ravines and gullies between the hills and ridges provide countless concealed avenues of approach. The waterlogged low ground cannot support vehicles and roads were few and crude. The Germans had occupied the area for three years and built a series of strongpoints in three belts. Only the first line was occupied. The second line was 10–12km west on the Titovka River while the third was another 20–25km west on the Petsamo River. These would be occupied as the Germans fell back.

The strongpoint lines were divided into battalion sectors (Abschnitt) with two reinforced company strongpoints and several platoon and half-platoon strongpoints with one or two interspaced between the company strongpoints. In the 2.Gebirgs-Division sector there were ten company strongpoints located atop hills. There was no depth to the strongpoint line, no mobile reserves and far too many concealed routes between strongpoints, the interval varying from 2–4km. These gaps were protected to some degree by patrols, obstacles, anti-personnel mines and indirect fire. When it became apparent that the Soviets would launch an offensive, a few additional positions were constructed and existing strongpoints improved. The Germans had only about one-third of the artillery the Soviets had, but they did have some air support.

The existing strongpoints were well built, being dug into rock. Some reinforced concrete positions had been built and most positions had heavy timber and rock overhead cover, the timber being brought from the south. Each strongpoint was self-contained with 360° fire and observation, and surrounded by barbed wire and mines. A serious problem was the rocky ground: it prevented the Germans from burying telephone lines, although it was run down trenches within strongpoints. Exposed wires would be cut by artillery and bomb fragments and command and control over the remote strongpoints would disintegrate. The Soviets had each strongpoint and its defences accurately plotted.

The strongpoints, manned by mountain troops, were usually oval in shape following the contour of their hilltop’s crest. They were surrounded by single and double-apron barbed-wire fences with anti-personnel mines. Trenches connected all rifle and crew-served weapons position and support facilities. Each strongpoint was armed with light and heavy machine guns, 8cm mortars, 3.7cm anti-armour guns and 7.5cm infantry guns. Ammunition and ration stocks were abundant and all units were at about 90 per cent strength.

The Soviets attacked on 7 October with overwhelming artillery and air support. By the end of the second day Soviet troops had infiltrated the strongpoint line and were crossing the Titovka River in the south to isolate the strongpoints to the north and east of the river. Attacks were still being launched against the strongpoints. Late on the 8th the Germans were ordered to withdraw westward. Few of the strongpoints fell to direct assault and such attempts cost the Soviets heavily. With no in-depth positions or reserves, with communications often lost, the Germans were unable to hold out once the Soviets had infiltrated and got behind them. The strongpoint line was supposed to hold for 14 days allowing corps service units to withdraw, but they held out for less than three.

As the First US Army approached the Third Reich’s frontier in September 1944, its divisions readied themselves to fight a vicious battle to penetrate the much-vaunted Westwall. While beyond the scope of this book, the existing Westwall defences were incorporated into the German defence line, and are briefly examined here.

The 400km-long Westwall is often pictured as seemingly endless lines of concrete dragon’s teeth anti-armour obstacles covered by countless massive reinforced concrete bunkers stretching the entire length of the German frontier. While posing a formidable obstacle, the Westwall was far from being continuous and as densely fortified as many feared. Defences were built in-depth from 2–20km, but were scattered in many areas and of uneven distribution. This depth is what gave the Allies the most difficulty, not the strength of the individual fortifications themselves. Largely built in the 1930s, by 1944 the positions were obsolete with most unable to mount anti-armour guns larger than 3.7cm. Many of the weapons on special mountings had been removed and employed in coast defences. Standard weapons could not always be mounted inside. The fields of fire were limited to 40–50° and could fire in only one direction, but were well-sited, covering key approaches. Casemated artillery positions were few in number and found covering only the most likely avenues of approach. The positions did have the tactical advantage of being over-grown with vegetation. Some additional work had been accomplished in the areas where attacks were most likely, especially in regards to additional anti-armour obstacles. Because of the limitations of the existing bunkers, coupled with the very real fear of being trapped in them, the Germans used them mostly as troop shelters and local command posts. They provided a central protected position around which field fortifications were dug. The bunkers were usually positioned in clusters of two tiers providing mutual support for adjacent bunkers. Trenches often linked bunkers within a cluster. Mutually supporting bunkers were usually 80–200m apart with second-tier bunkers 100–500m behind. There were gaps though between clusters of bunkers. The bunkers could be from less than 30m to up to 400m behind the anti-armour barrier (comprising anti-armour ditch, 4–6-row dragon’s teeth, stone wall, steep-banked river, tank-proof dense woods, or railroad embankment). In sectors offering good infantry approaches from covered areas double-apron barbed wire was emplaced using steel picket posts. The Germans did an excellent job of tying the defences into natural terrain obstacles to limit the number of man-made obstacles built.

While there were many types of concrete fortications employed on the Westwall, those covering the defence zone usually contained a 3.7cm gun (mostly removed with a machine gun substituted) plus a machine gun or just a single machine gun in the battle room, one or two rooms for troop quarters, ammunition room, storage locker, and a gas-proof vestibule with one or two entrances. Most had an emergency exit. Walls were 2m thick and the roofs 2.5m. They were semi-sunken with most of the above-ground portion covered by sodded-over earth. They sometimes had a building façade built around them for camouflage. Tunnels did not connect them. Telephone cables buried up to 2m deep connected all positions and command posts. They contained folding bunks, lights (though generators had often been removed), tables, benches, wall-mounted telephones, stoves and gas filter systems. Five to seven men manned most. Three were on watch with the remainder inside resting. When shelled all sought cover inside. When attacked all but the machine gunners left the bunker and occupied field works. The doors were often unprotected from direct fire by exterior blast walls or trenches. A tank or bazooka round could penetrate the steel doors.

Strongpoints were prepared around bunkers or bunker clusters and small clumps of woods. These consisted of L-, V- and W-shaped rifle, machine-gun, and Panzerfaust/Panzerschreck positions covering all approaches. Some positions were dispersed along roads leading into the strongpoints and the roads were mined with many being booby-trapped. Anti-armour ditches were sometimes defended with firing steps and dugouts cut in their sides. Mortar positions were located to the rear to cover the approaches to the strongpoints and gaps between clusters. In areas where the risk of attack had originally been deemed slight there were fewer permanent fortifications and field works were denser.

Table 3: defences of Palenberg, Germany

1,500m anti-armour ditch

600m anti-armour ditch with a 700m ditch 600–800m behind it

1,500 and 600m sections were tied into railroad embankment

30 machine-gun bunkers (6 forward of anti-armour barrier)

8 machine-gun bunkers in second-line cluster north of Palenberg

5 troop bunkers (3 forward of anti-armour barrier)

1 open position with 3 x 2cm flak guns

To provide an ‘ideal’ model of what the permanent fortifications entailed, a 3km section of the Westwall at Palenberg, a small coal mining town 13.5km north of Aachen, defended by the 49. Infantrie-Division, is examined here – the point where the 30th US Infantry Division attacked. The terrain was gently rolling, mostly open ground. The scattered narrow bands of woods were incorporated into the anti-armour barriers. The Wurm River ran in front of the defences, but while only 10m wide, its steep banks and marshy adjacent ground provided an excellent tank obstacle. All bridges had been blown. A steep-sided double railroad track embankment traversed the width of this sector running parallel with the Wurm and was tied into anti-armour ditches. There were no dragon’s teeth in this sector. The bunkers were by no means evenly distributed across the front, but sited to cover the most likely avenues of approach. Grenadier and machine-gun battalions defended the sector backed by significant artillery with some armour in reserve.

A company hilltop strongpoint

Stutzpunkt Zuckerhutl was typical of the company strongpoints in the far north of Finland in 1944. It was surrounded by two parallel double-apron barbed-wire fences with anti-personnel mines. A firing trench revetted with rock and mortar ran around the entire perimeter with communications trenches connected to support positions in the centre. The defenders were a 1st Mountain Infantry Regiment, 2nd Mountain Division rifle company reinforced with a pioneer platoon, crew-served weapons from the battalion, and artillery forward observers. They were armed with 13 light and 8 heavy machine guns, two 8cm mortars, two 3.7cm anti-armour guns and two 7.5cm infantry guns, the normal allocation of weapons from the battalion heavy companies and the regimental anti-armour company. Two-man firing positions and machine-gun bunkers lined the perimeter. The reason for the apparently irregular spacing of these positions is their siting to cover the approaches across broken terrain. Troops were quartered in various support bunkers and two-squad bunkers. Note that the command post is on the forward perimeter enabling the commander to directly observe the enemy. The large red arrow indicates the direction towards the enemy (feindwärts).

Westwall defences, Germany, October 1944. The 1,100m2 area shown lies immediately to the south of Palenberg. The moated Rimburg Castle, to the centre left, was heavily defended, as was the large farm complex to the upper right of the castle. The Wurm River flows through the upper left area – itself an obstacle with its bridges blown. The double railroad tracks were on an elevated embankment, which was incorporated into the defences to form an anti-armour obstacle. Where the embankment is low an anti-armour ditch was built (the heavy grey line in the lower left). The end of a second-line anti-armour ditch is visible in the lower right corner. Ten concrete bunkers within this square covered the railroad embankment and anti-armour ditch, and a further one is shown covering the second-line anti-armour ditch. Some six or so rifle, machine-gun and Panzerschreck positions were dug around these bunkers, with some of them connected by trenches.

The US 30th Infantry Division attacked in this sector on 2 October after conducting extensive rehearsals and weapons training. Casualties were heavy the first day with many sustained by intense artillery and mortar fire. A foothold was secured within the defences even though supporting tanks experienced difficulties crossing the Wurm. Heavy machine-gun fire was directed on the bunker firing ports while mortars and machine guns suppressed adjacent field works. Three or four tanks or tank destroyers supported a rifle platoon attacking a bunker with bazookas, satchel and pole charges, and flamethrowers. Often the latter had only to fire a burst into the air and the Germans surrendered. 105mm self-propelled howitzers were especially useful for engaging bunkers. Most bunkers were blown once seized up using 1,200lbs (544kg) of TNT to prevent their recapture and use.

The defences of a German town annotated by US aerial photo interpreters. Warehouses are located on the left edge above a railway yard. A row of houses stretches to the right of the warehouses and more dwellings can be seen in the lower right. The continuous, barbed-wire protected, first-line trench stretches across the photo’s top with machine guns positioned in pairs. A position containing three 2cm Flak guns is in the upper right. Communications trenches run to the rear: these also served as flanking-fire trenches in the event of an Allied penetration of the first line. The second trench line covers the anti-tank ditch and it was from here that counter-attacks would be launched. The anti-tank ditch is linked to the row of houses and the warehouses, which probably have strongpoints located within some of the buildings. There were also probably mines and anti-armour obstacles blocking passages between buildings. Oddly, mortar positions are located forward of the second line.

The Germans counter-attacked that night supported by armour, but failed to dislodge the Americans. German morale was initially high, but once the main defence zone was penetrated their morale began to suffer. The defences had been completely penetrated in the 30th Infantry Division’s sector by 6 October. At that time the division swung south and began rolling up the flank and rear of the Westwall defences rather than continuing to advance eastward as the Germans expected. This unanticipated move caused German morale to rapidly crumble. By 16 October the division had cleared an area 12km south to the outskirts of Aachen from its original penetration of the Westwall and linked up with the 1st Infantry Division. The division had suffered 2,030 casualties, fewer than forecast, and created a 13km-wide breech into Germany. The Americans evaluated that the permanent fortifications, though extensive, only enhanced the German defence by 15 per cent over defences comprising field works only. Dug-in German tanks and assault guns were given an efficiency rating of 40 per cent and considered much more troublesome than bunkers.

This hastily built MG.34 position in Germany possesses a good field of fire, but is poorly camouflaged because of the exposed spoil around its forward parapet.