Blood Red, Soothing Green, and Pure White: What Color Is Your Operating Room?

Jeanne Kisacky

Chapter Summary. Until the early twentieth century, in the interests of cleanliness, operating rooms in American hospitals were all-white affairs. Between the 1910s and 1920s, doctors, hospital architects, and hospital consultants debated different colors for operating rooms as a means of reducing glare and improving the surgeon’s vision. While some continued to champion “whiteness,” many considered a blue-green color (the complementary color to blood) as a better, more “scientific” color choice. In the end, this debate reveals a shifting cultural configuration of color and sickness—as blue-green became the color of surgery, white shifted from signifying clean to standing for the uncomfortable sterility of the hospital.

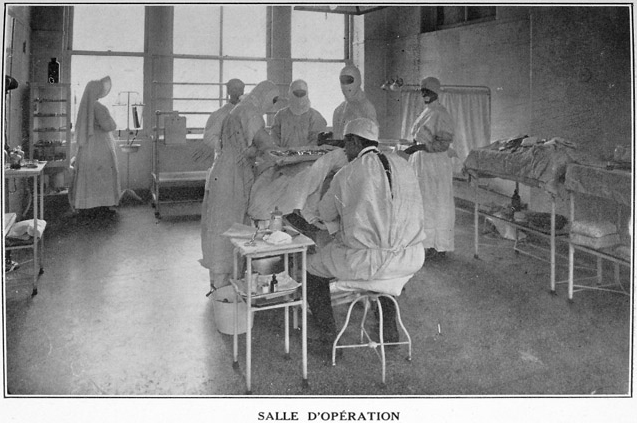

“White is the color of cleanliness,” wrote Miss M. E. McCalmont, a nurse and hospital superintendent, in 1913.1 She did not mean it figuratively. In the early twentieth-century hospital, interest in aseptic (germ-free) conditions gave the traditional Western cultural equation of white with purity a new hygienic field of operation. White made dirt visible, this visibility promoted hygienic vigilance. As one practitioner put it, “An all-white operating room will lend itself to habits of cleanliness better than any other color, because dirt of any kind will obtrude to such an extent that the nurses or cleaners will have to remove it.”2 In turn-of-the-century surgical spaces, white paint, white tile, white furniture, white uniforms, and white linens were ubiquitous. The most prestigious hospitals installed expensive white marble everywhere—walls, doors, floors, ceilings, and trim.3 White was an aseptic billboard; absence (of color, germs, dirt) was the message. See Figure 9.1.

But there was a problem with white surgical spaces; they were literally a pain in the eyes for the doctors. Operating rooms required shadow-free illumination of high intensity. In nineteenth-century hospitals, large windows and skylights provided extensive daylighting. By the early twentieth century, the skylights and windows grew larger while powerful electric lights also ringed the operating table. The glare from the all-white surfaces during surgery caused intense fatigue and eyestrain. That was dangerous. A surgeon who looked up from the wound to the glaring white walls might “find his eyes useless for a moment” when he looked back to “the less well illuminated wound.”4 But if not white, what color was an operating room to be? And why?

Figure 9.1 The all-white operating room of the French Hospital in New York City is relatively dimly lit, lessening the glare. From French Hospital, New York City, Société Française de Bienfaisance de New York. Rapport Annuel du Président, 1915, fp. 3.

In the early 1910s, to reduce glare, Dr. Carrell at the Rockefeller Institute in New York City covered his surgical subjects (lab animals) with dark cloths and operated in a dark green room.5 By July 1914, he was using black garments and linens in his operations on people. At the same time, Dr. H. M. Sherman inaugurated the use of spinach green walls in St. Luke’s Hospital, San Francisco. See Figure 9.2. Why dark green? According to Dr. Sherman, an operating room’s color scheme “should start from the red of the blood and of the tissues.” He chose spinach green, because it was complementary to, and thus would not visually compete with, hemoglobin or blood red. He also experimented with dark green linens, but because the green did not withstand steam disinfection, like Dr. Carrell, he resorted to black gowns, black sheeting, and black towels. The green room was soon the favorite of the hospital’s operating rooms; “no one who could get into the green room to do an operation ever went into the white room.” Doctor Sherman tried to explain the clear preference by speculating that the green lower walls, with bright (white) upper walls and ceiling, imitated “the optical environment out in the fields or among low bushes, where the ground of the surroundings, to above the level of the eyes is green, and the sky overhead is full of white daylight.” This was the “natural” environment for eyes.6

The colorful craze spread. The Edward W. Sparrow Hospital of Lansing, Michigan, got Dr. Sherman’s scheme upside down—its operating room had “white tiled floors and high, white vitrified tile wainscoting,” but above that the “walls and ceilings are painted a soft but decided green.”7 Champions of other colors appeared. In 1915, hospital consultant Oliver Bartine agreed with hospital architect Meyer J. Sturm that colorful operating rooms were useful, but rather than green, they suggested that “the walls should be treated in light tan color, with straw-color ceiling.”8 Another expert recommended a dull gray floor and lower walls with a darker gray above.9 By 1918, experts confidently stated “a soft gray or light green color” was “more suitable than white for the walls of operating rooms.”10

Figure 9.2 Dr. H. M. Sherman’s spinach green operating room and black linens and surgical garb in St. Luke’s Hospital, San Francisco, 1914. From “Green and Black Operating Colors,” Modern Hospital, 3/1 (July 1914): 67.

Nevertheless, champions of “whiteness” remained. In 1915, St. Mary’s Hospital in Green Bay, Wisconsin, proudly announced its use of white glass walls for its new operating room.11 In 1917, Texas doctor William Lee Secor broadened the argument for white. He noted that the original all-white operating room had been part of a spatial solution to the lighting problems of pre-electricity days—the large windows and the reflective white surfaces maximized daylight. By the 1910s, numerous experiments had also established that exposure to sunlight (and its UV rays in particular) killed microorganisms. White walls, by reflecting daylight, maximized this sterilizing effect. Secor worried that “to tint the walls of an operating room…makes it much more difficult to keep the room clean and sterile.” Colored walls hid the “macroscopic” dirt and, by darkening the room, interfered with the natural germicidal influence of bright light. Secor’s solution to the problem of all-white rooms was straightforward: “to obviate the effect of the glare we have used beaks on our caps, and on bright days large amber-tinted spectacles are worn.”12

The difficult interaction between color and lighting in the operating room created yet another problem. Color perception of the bodily tissues during surgery was critical to the surgeon’s assessment of the patient’s conditions. Daylight, or full spectrum light, provided accurate color perception, and white rooms with lots of windows provided daylight in abundance. Some worried that altering the colors of the operating room would alter the color of the light, and thus distort the surgeon’s color perception of the surgical wound.13 Others worried that colored operating rooms would be too “dark.” In late 1915, Oliver Bartine published the light absorption rates of different colors as a warning against redoing operating room color without considering the effects on a room’s ambient light.14 In response, hospitals installed more and stronger supplemental artificial lights. The increased use of non-full-spectrum artificial lights provided yet another source of color distortion and brought back the original problem; when brilliantly enough lit, even green rooms had glare.15

Green, however, was increasingly hard to escape even though the exact shade varied. Between 1915 and the early 1920s the Chicago Lying-In Hospital had a delivery room painted in grass green; the hospital of the Iowa State College had a moss green operating room; another hospital reported a two-tone scheme with “dead-faced green” on the lower walls and a lighter green above.16 Dr. Sherman stuck with his spinach green, noting that not only was it the complement of blood, it was a “mid-spectrum” color (then touted by several color theorists as the most desirable color range).17 It wasn’t until 1924 that Dr. Paluel J. Flagg, a New York doctor, used the new Munsell Color System to determine “scientifically” that the complement of blood-red was a blue-green. Dr. Flagg named it “eyerest” green.18 (The ubiquitous blue-green scrubs of late twentieth-century hospitals are a clear indicator of the winning green).

The shift from white to green operating rooms was made in the interest of utilitarian scientific practicality. Color, however, is rarely a wholly scientific, practical undertaking. Any extensive use of a specific color (like the hospital’s ubiquitous adoption of white or green) inevitably altered its cultural resonance. While green was being popularized “scientifically,” white was being reinterpreted culturally. As early as 1914, architect Robert J. Reiley, noted that the standard white enamel hospital interior had become “repellant to patients.”19 By the 1920s, William O. Ludlow, another architect, thought that white suggested sterility and coldness, “and [lacked] all power to create pleasurable and helpful sensation.”20 White was harsh, sterile, inescapable; it created a “hyper-aseptic atmosphere.”21 Hospital expert Wiley E. Woodbury made the cultural shift explicit when he commented that “glaring white walls and white enameled furniture are suggestive of sickness.”22 Excessive whiteness might even be harmful. M. J. Luckiesh stated that white in overabundance had proven psychological ill effects. Ludlow suggested that the “unbroken whitened sterility of walls and ceiling produces sterility of thought in the sick mind.”23 If hospitals had made green the color of surgery, they had also strengthened white as the color of cleanliness, but of a cleanliness so extreme as to be discomforting, sickening.

NOTES

1. M. E. McCalmont, “Practical Details in Hospital Planning and Equipment,” Brick Builder, 22/7 (1913): 161.

2. “All-White Operating Rooms,” Modern Hospital, 2/1 (January 1914): 45.

3. The world-famous Syms Operating Theatre of Roosevelt Hospital, in New York, (1891) was perhaps the most notorious use of extensive white marble.

4. “Green and Black Operating Colors,” Modern Hospital, 3/1 (July 1914): 67. With the advances of anesthesia, asepsis, and surgical technique, the increasing duration of surgical procedures compounded the problem. While early nineteenth-century surgeries had often been measured in minutes, early twentieth-century surgeries were measured in hours.

5. “All-White Operating Rooms,” 45.

6. “Green and Black Operating Colors,” 67–68.

7. Maude Landis, “The Edward W. Sparrow Hospital, of Lansing, Michigan,” Modern Hospital, 5/4 (October 1915): 236.

8. Oliver H. Bartine, “Artificial Illumination in Hospital,” Modern Hospital, 4/1 (January 1915): 47.

9. “Operating Room Floors,” Modern Hospital, 8/2: (February 1917): 148.

10. “Redecoration of Operating Room,” Modern Hospital, 11/2 (August 1918): 150.

11. “Green Bay Has New Hospital,” Modern Hospital, 4/1 (January 1915): 50.

12. William Lee Secor, “The White Operating Room,” Modern Hospital, 9/3 (September 1917): 171. The caps were similar to the “Mayo Caps” worn at the Mayo Clinic.

13. M. Luckiesh, “Artificial Daylight in Surgery,” Modern Hospital, 9/4 (October 1917): 311–12.

14. Oliver H. Bartine, “Hospital Construction,” American Architect, 108/2077 (October 13, 1915): 241.

15. Luckiesh, “Artificial Daylight,” 311–12.

16. “Operating Room Floors,” 148; “Chicago Lying-In Hospital,” American Architect and Building News, 108/2079 (October 27, 1915): 283; W. R. Raymond, “The Iowa State College Hospital,” Modern Hospital, 17/1 (July 1921): 4.

17. Harry M. Sherman, “The Green Operating Room at St. Luke’s Hospital, San Francisco,” Modern Hospital, 11/2 (August 1918): 97–98. Sherman cited works on color theory and the physiology of color perception by Hering, Landon, Heckel, Risley, and Cutting.

18. Paluel J. Flagg, “A Scientific Basis for the Use of Color in the Operating Room,” Modern Hospital, 22/6 (June 1924): 555–59; “Correct Color for Operating Room,” Modern Hospital, 28/5 (May 1927): 56.

19. Robert J. Reiley, “The New Hospital of the House of Calvary,” Modern Hospital, 3/2 (August 1914): 82.

20. William O. Ludlow, “Color in the Modern Hospital,” Modern Hospital, 16/6 (June 1921): 511.

21. M. Luckiesh and A. J. Pacini, “How the Light and Color Improve the Patient’s Room,” Modern Hospital, 29/6 (December 1927): 116; Frank E. Chapman, “Hospital Planning and Its Trend,” Architectural Forum, 49/6 (December 1928): 829.

22. Wiley E. Woodbury, “Some of the Special Departments of a General Hospital,” Architectural Forum, 37 (December 1922): 272.

23. William O. Ludlow, “Some Lessons the War Has Taught,” Modern Hospital, 12/4 (April 1919): 283.

REFERENCES

“All-White Operating Rooms” (1914, January), Modern Hospital, 2/1: 45–46.

Bartine, Oliver H. (1915, January), “Artificial Illumination in Hospital,” Modern Hospital, 4/1: 46–48.

Bartine, Oliver H. (1915, October 13), “Hospital Construction,” American Architect, 108/2077: 241–46.

Chapman, Frank E. (1928, December), “Hospital Planning and Its Trend,” Architectural Forum, 49/6: 827–32.

“Chicago Lying-In Hospital” (1915, October 27), American Architect and Building News, 108/2079: 283–84.

“Correct Color for Operating Room” (1927, May), Modern Hospital, 28/5: 56.

Flagg, Paluel J. (1924, June), “A Scientific Basis for the Use of Color in the Operating Room,” Modern Hospital, 22/6: 555–59.

Flagg, Paluel J. (1939), “Color in the Operating Field,” Modern Hospital, 52/6: 75–80.

“Green Bay Has New Hospital” (1915, January), Modern Hospital, 4/1: 50.

“Green and Black Operating Colors” (1914, July), Modern Hospital, 3/1: 67–68.

Landis, Maude (1915, October), “The Edward W. Sparrow Hospital, of Lansing, Michigan,” Modern Hospital, 5/4: 235–38.

Luckiesh, M. (1917, October), “Artificial Daylight in Surgery. Nearest Approach to Daylight Desirable Where Color Discrimination Is Required—a Study in Color Development,” Modern Hospital, 9/4: 311–12.

Luckiesh, M., and A. J. Pacini (1926), Light and Health: A Discussion of Light and Other Radiations in Relation to Life and to Health, Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins.

Luckiesh, M., and A. J. Pacini (1927, December), “How the Light and Color Improve the Patient’s Room,” Modern Hospital, 29/6: 116.

Ludlow, William O. (1919, April), “Some Lessons the War Has Taught. In Time of War Prepare for Peace—War Time Psychology Forced Us to Think of Men in Terms of Groups, but It Is the Individual Soul That Counts in Every Sphere, Including Hospitals,” Modern Hospital, 12/4: 283–84.

Ludlow, William O. (1921, June), “Color in the Modern Hospital,” Modern Hospital, 16/6: 511–13.

McCalmont, M. E. (1913), “Practical Details in Hospital Planning and Equipment. Part II—General Continued,” Brick Builder, 22/7: 158–61.

“Operating Room Floors” (1917, February), Modern Hospital, 8/2: 148.

Raymond, W. R. (1921, July), “The Iowa State College Hospital,” Modern Hospital, 17/1: 1–6.

“Redecoration of Operating Room” (1918, August), Modern Hospital, 11/2: 150.

Reiley, Robert J. (1914, August), “The New Hospital of the House of Calvary. An Institution for the Treatment of Sufferers from Cancer, Where, Although in Every Respect a Modern Hospital, It Has Been Sought to Create the Atmosphere of a Home,” Modern Hospital, 3/2: 79–82.

Secor, William Lee (1917, September), “The White Operating Room. Suggestion of Remedy for Its Defects—Beaked Caps and Amber-Tinted Glasses Used to Obviate Effect of Glare from White Walls,” Modern Hospital, 9/3: 170–71.

Sherman, Harry M. (1918, August), “The Green Operating Room at St. Luke’s Hospital, San Francisco,” Modern Hospital, 11/2: 97–98.

Woodbury, Wiley Egan (1922, December), “Some of the Special Departments of a General Hospital,” Architectural Forum, 37: 271–76.