FEELING GOOD: THE POSITIVE AFFECTS

Once Tomkins figured out the basic nature of the affect system it became necessary to study adult emotion in an entirely new way. Everything we thought we knew about emotion turns out to be at least slightly wrong. Some of the experiences we have called “shame” turn out to be combinations of shame affect with other affects, stored and remembered in their own particular way, while many, perhaps most, of the uncomfortable moments made so by shame affect—emotional experiences every bit as miserable as the ones we know so well—never achieve the recognition of a label or name. I can assure you of one thing: The affect Tomkins calls shame–humiliation is utterly and completely involved with the positive affects of interest–excitement and enjoyment–joy. Shame feels so miserable because it interrupts what feels best in life. But there is no way of understanding shame until you learn about excitement and contentment, about the pleasures with which it interferes.

INTEREST–EXCITEMENT

Whatever causes an optimal increase in the intensity and rate of activity of anything going on in the brain will trigger the affect interest. The information capable of providing such a stimulus for the infant may come from situations we can figure out, like a chance sound in the room, a bright object above the infant’s crib, or the smell of mother, but interest may be triggered by a slight increase in hunger, by an image remembered, or by other internal sources of stimulation we may never discern. Nonetheless, when the proper conditions are met, the affect is triggered: The infant’s eyebrows lower, the face takes on the attitude of rapt attention, and the entire child seems to be tracking something.

The affect interest makes us more interested in whatever is going on, and, if interest has been triggered by the face of another person, these two people will now be locked in the highly pleasant state of mutual interest that is the forerunner of social interaction. Whatever has triggered this degree of interest is now linked or assembled with it, making it interesting by amplifying it in an optimal fashion. Interest can make us pleasantly hungry, excited to see an old friend when memory presents the proper cascade of neural stimulation, fascinated by a puzzle with problems that create stimulation within a certain range of neural activity.

The more mature the child, the more memory can be “brought to mind” when interest is triggered. Early in development memory seems to be stored as groups of images, rather than words, so we believe the interested infant is comparing the focus of its interest to whatever is already in storage or, when necessary, making new categories of memory. With increased maturity comes vast expansion of memory and, therefore, the potential for growing complexity of affect–experience linkages. Whereas each episode of affect is an identical, short-lived event, the addition of related memories defines the more complicated and longer-lasting phenomenon we call an emotion.

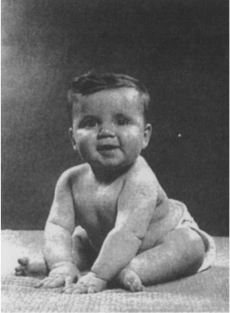

Fig. 3.1. Brow slightly furrowed, gaze riveted on whatever has triggered interest–excitement, mouth partially open. Often the tongue is thrust to the comer of the mouth.

Fig. 3.2. Ready to spring out of his potty chair in excitement, this little boy demonstrates the same affect at the upper end of its range.

An excited mood can be sustained when some external situation like an entertainment provides constant novelty or some internal source produces new thinking, as in the case of creativity. Anybody who writes, paints, composes, dances, or invents will gladly tell you how life can be taken over by the excitement generated in the wake of such novel thoughts. So alien to one’s normal life can be the excitement of creativity that the ancient Greeks believed new ideas and the emotionality associated with them were the gift of an external being called the Muse. When we say that someone has been “struck by the muse” we mean to indicate that this person is “helplessly” excited by the new ideas constantly triggering the affect interest–excitement.

Are there disorders of this mood, situations when excitement or interest have been triggered in the absence of real novelty? Often, as a psychiatrist, I have treated people with what we used to call manic-depressive illness, nowadays labeled bipolar affective illness. When these patients are depressed, they complain that nothing interests them, that they are incapable of becoming excited about anything. And in the manic phase of the illness, they experience an opposite reaction—everything is interesting, everything that occurs to them can be exciting. When manic, they think with extraordinary speed; when depressed, thoughts flow like molasses in January. Affects are contagious. Just being around someone with an intense affect will make us share that part of his or her experience. Anyone who has ever been around even mildly manic or moderately depressed people will tell you how quickly we are drawn into their mood.

In this illness, both the decreased ability to be interested and the increased ability to be interested are part of a biological disorder of mood now thought to be caused by interference with the metabolism of one of the neurochemical messenger systems, a disorder often normalized by the addition of lithium salts to one’s diet. So far as I can determine, since the innate affects provide the vocabulary for all normal emotion, no matter what interferes with or triggers inappropriately our experience of emotion, it is interpreted by us as some sort of affect. And this affect feels to us as if it were normal innate affect. What I find fascinating is that a problem in the circuitry of the brain, perhaps in the manufacture of a single chemical, leads to a distortion of normal mental experience that the patient can interpret only in terms of his or her lifetime experience of innate affect.

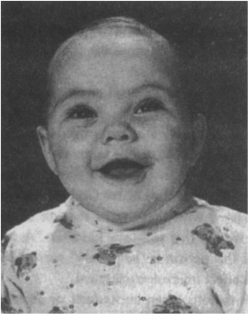

Fig. 3.3. The face of enjoyment–joy is always described as bright, or shining, muscles relaxed, lips open and widened. You wouldn’t be surprised if this child laughed a moment after the picture was taken.

Is there a difference between the excitement felt and exhibited by an inventor rushing toward discovery and the excitement felt and exhibited by someone who, through a disorder of neurotransmitter function, has been made hypomanic? Not at the level of innate affect mechanisms, for the identical affect has been triggered in each case. For the inventor, interest has been stimulated by the onrush of ideas. Occasionally these novel ideas, when amplified by interest, trigger more and more novel ideas, leading to intense excitement and the quite pleasant “high” of discovery. However, we call hypomania an illness because the intense interest and excitement are brought on by alterations in neurotransmitter function—the ideas expressed by the individual are the result of the excitement rather than the source of it. Rarely are they truly creative or truly useful, and the more severely manic the individual, the less clearly reasonable will be the ideas involved.

You will recall that one of the cardinal features of affect is that by its ability to amplify anything with which it is linked, affect is responsible for attention. Anything that may be said to occupy our attention has taken center stage and become the subject of consciousness simply because it now has affective amplification. So far, we have only considered the type of attention produced by one affect, interest–excitement; but it is intuitively perceptible that each of the other affects we have yet to discuss also produces its own quite specific form of attention and therefore its own form of consciousness.

Once thought to be only a disorder of childhood, the spectrum of conditions called attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADD or ADHD) may be reconceptualized in terms of the affect system. These children seem unable to focus attention on anything for more than a moment. We adults know boredom as a state in which there is an insufficient amount of novelty to trigger ongoing interest–excitement. When bored, we search for the sort of stimulus, of data flow that we call distraction. Children with ADHD seem distracted by stimuli most of us would fail to notice, and are unable to maintain interest–excitement in situations the rest of us would find compelling.

The hypomanic patient’s excitement seems to devolve from a constant and ongoing excess of the chemicals normally released only when the affect has been triggered by data flow—the conditions of stimulus gradient described by Tomkins. Manic hyperactivity is the result of the correlative function of affect; anybody is physically active when excited, no matter what the source of the excitement. Children with ADHD are hyperactive because affect has been triggered for some other reason. They are hyperactive simply because their attention shifts rapidly from one source to another and because the correlative function of interest–excitement raises their activity level.

Anything characterized as a problem with attention must somehow involve the affect system. All of the medications used to treat these children involve the neurotransmitters associated with the maintenance of normal affect mechanisms. Most of those who work with ADHD are pediatricians, pediatric neurologists, child psychiatrists, or child psychologists—all of whom tend to stop working with patients beyond early adolescence. Now we are beginning to consider the possibility that certain conduct disorders of adolescence and young adult life may represent the adult manifestations of ADHD. And those who treat this group of patients tend to prescribe the same group of medications as is used for the childhood disorder.

Most investigators approached ADHD as if it were analogous to the pediatric disorder known as infantile colic. Colicky babies cry constantly, distress–anguish apparently triggered by some failure of gastrointestinal development. Kids grow out of colic—indeed, the treatment consists mostly of calming the parents who are locked to a baby for whom solace seems so woefully inadequate. Colic usually disappears after a few months; we think it simply takes that long for some pattern of neural or digestive maturation to be completed. And there is no evidence that colicky babies grow up to be colicky adults. Since most children with ADHD seem to get better as they grow older, we have until recently paid little attention to the adult manifestations of this condition.

My own guess is that ADHD represents a genetic disorder of firmware, of the internal scripts responsible for normal affect. Although we treat these children and adolescents by making alterations in hardware function (using one or another form of artificial chemical mediator substance), it may be that the real source of the disorder is in the circuitry for affect stability. Tomkins introduced the concept of the central assembly, the parts of the brain responsible for affect utilization and the maintenance of attention. I suspect that ADHD may be linked to this locus of neurological function.

All through the history of medicine we have been able to learn about normal function through the analysis of disease. (Our earliest understanding of glucose metabolism and the role of insulin was made possible by the study of diabetes mellitus.) ADHD may be the sort of condition that allows us to peer into the circuitry for normal affect in a way offered by no other clinical entity. I have begun to discuss such research at a number of clinical centers.

Normal interest and excitement are always around us. Whether or not you have any interest in astronomy, it is hard not to be caught up in the exhilaration generated by an impending solar eclipse. Magazines, television, and newspapers all carry instructional material that can let even the least scientific among us get some understanding of the factors involved in this monumental exercise in space geometry. The total eclipse of 11 July 1991 was the longest in our lifetime, and its path over some of the most heavily populated regions of our planet let millions see it.

Reports from those who have seen such spectacles often contain information about the emotional reaction of observers. Almost universally, eclipse-watchers mention a rising tide of excitement as totality approaches. In the December 1991 issue of Sky and Telescope, columnist Dennis diCicco quotes one amateur astronomer: “The shadow came down on us over the ridge of mountains to the west enveloping everything in a single indrawn breath. The diamond ring flashed, followed by unbelievably delicate and gossamer coronal streamers stretching, stretching everywhere. Now everyone was yelling, hollering, screaming, pointing. ‘Look at that!’ ‘Look at this!’ ‘Look there!’ Just look! LOOK! . . . No grammatical gymnastics of mine can begin to describe what I saw in those precious, fleeting minutes” (p. 589).

But another astronomer, equally sensitive to the onrush of excitement felt by observers, pointed out something different: “We watched as a huge double sunspot group, perhaps 20,000 miles long, swam toward the Moon’s black rim (perceptibly wrinkled by mountains) and was swallowed, followed by two single tiny spots and another great group . . . I realized more clearly than ever before that it is the acceleration of the dimming daylight that drives the excitement” (p. 594, emphasis in original). Tomkins himself could not have said it better.

From its name you might think that Tomkins’s label for this affect is synonymous with such vaguely defined conventional terms as “happiness.” Far from it. It is a technical term, like interest–excitement in that it is a name for another highly specific biological condition. I ask you to accept the idea that anything capable of causing a decrease in the rate and intensity of neural firing in the brain of infant or adult will trigger the response of a smile, with the lips slightly opened and widened—a pattern Tomkins calls the affect enjoyment–joy. Perhaps a better term for the weaker forms of this affect would be contentment, which is less likely to be confused with the social phenomenon also (and more conventionally) called “enjoyment.”

I ran across a Latin proverb in an early 19th-century medical dictionary that conveys some of the sense of this affect: Omne animalium languo post coitum— all animals are calmed after intercourse. Do we need such a complex theory of emotion to tell us that an orgasm can leave us with a feeling of contentment? Surely not. But this theory does help explain in what way all feelings of calm resemble each other. Again, observe the infant and note that every time distress is relieved, the baby smiles and becomes calm. No matter what the source of distress, relief produces contentment. Similarly, the reduction in stimulus level accompanying the relief of any high-density experience will trigger the smiling face of enjoyment–joy and the calm spirit of contentment.

At times this experience of affective response to stimulus decrease will range from tinkling laughter to uproarious guffaw, while at other times we will barely smile. Darwin commented that monkeys also laugh and that they exhibit something like a smile; both he and other investigators have suggested that the smile is a milder or attenuated form of laughter. Tomkins believes that our ability to smile is the result of further evolution of this affect, and that the more sudden and dramatic the decrease in stimulus level, the more likely we are to laugh.

The laughing, smiling face of enjoyment functions to enhance social relatedness, much as does interest–excitement. Again, if you watch mothers and babies playing at face-to-face interaction, you will notice that they spend a great deal of their time oscillating between these two affects. Tomkins has commented that shared interocular contact—people merely gazing at each other—is the most intimate of human activities. How easy is this to understand when we recognize that the wonderful process of empathy depends entirely on the fact that each of us shares with the other this identical group of affect mechanisms.

Even though mothers and babies play at bouncing affect-based messages back and forth between them and thus learning a great deal about the feeling states going on in each other, their interaction is not limited to affective communication. The game of “making faces” at each other is quite complex. It seems that babies are true artists and experimenters—from the moment of birth on they seem to enjoy making up new combinations of facial expressions and bodily motions. Some of these expressions may involve the intentional display of an affect (used more in the spirit of a game than to indicate the presence of a feeling), while others will be quite unrelated to the facial displays of innate affect. Each mother-infant couple develops its own thesaurus of non-affect expressions, a shared vocabulary of meaningful looks and glances that grows in complexity and importance as the child matures. The interpretation of these expressions will depend on the history shared by this twosome—but whenever an innate affect is experienced and expressed by one, its meaning will be known unequivocally to the other.

What we as individuals call “having fun,” or an entertainment, usually involves something quite different from the affect Tomkins calls enjoyment–joy. Good times are characterized by frequent shifts between stimulus increases and stimulus decreases, producing sequences of excitement and contentment. When we watch a sporting event our attention is captured by the action on the field, which triggers interest by its novelty. Although it is true that by the time we are old enough to watch games we have a pretty good idea of the range of possible happenings (so that very little goes on outside an expected frame of reference), what does occur is unpredictable within certain limits. And it is that degree of unpredictability which triggers interest. Similarly, when an action is completed to our satisfaction (the outfielder catches a ball, the hitter does well, the goal is achieved, etc.), the immediate reduction in stimulus level produces the affect of enjoyment.

At the level of innate affect it really does not matter whether a splinter has been removed from one’s finger, or a burp has reduced the pressure in baby’s tummy, or a chiropractic manipulation has clicked something back in place, or a patient recovering from anesthesia realizes both that he or she has survived the procedure and that the surgeon has removed the source of terrible pain, or the punch line of a joke has caught us off guard and suddenly reduced the intensity of our attention. Each is an example of stimulus decrease; each a source of enjoyment affect.

Have you ever had a prolonged massage administered by a trained professional? Apparently my vertebrae never quite learned to hang in a straight line, and I endure a significant degree of chronic muscular discomfort. At regular intervals I will treat myself to a massage, and such treatment dissolves for a while the constant, low-grade pain with which I live. “Low-grade pain” is a fine example of what in Tomkins’s language would be called a constant level of stimulus density, and the relief of this pain triggers such a profound degree of “relaxation” that it takes me hours to return to my normal level of activity and alertness! The degree to which we are affected by enjoyment–joy is directly proportional to the intensity and prior duration of the preexisting level of stimulus. Does enjoyment–joy involve endorphins? Maybe so. I doubt morphine itself could have affected me more profoundly than the feeling of the first massage from which I arose completely relaxed and without pain.

This might be a good moment to repeat something I said earlier. Each of these first six affects is described by Tomkins as an analogue of its stimulus condition. Thus, enjoyment–joy is triggered by reduction in the level of intensity of any stimulus, and the affect itself produces a further reduction in all brain activity. It was easy to accept that interest–excitement amplified the condition of stimulus increase, but we have to bend our understanding of the concept of amplification to accept that enjoyment–joy can amplify a decrease in neural stimulation. This is the reason Tomkins describes the innate affects as analogic amplifiers of their stimulus conditions. Admittedly, this is a complex language. But what I like about it, and the reason I keep bringing it up from time to time, is that it seems to explain every single phenomenon ever observed in the realm of emotion. The importance of this will become increasingly clear as we proceed.

All of the examples noted above feature situations in which the decrease in stimulus level triggers enjoyment–joy, even though each one of these pleasant experiences will feel somewhat different. This is because each of these experiences represents the assembly of the affect with different sources and in different adventures. Emotion is defined by its context and its history, while affect is not.

As an affect, of course, joy is short-lived; recognition of the affect produces a somewhat longer feeling of pleasure, which is expanded into a pleasant emotion as we reflect upon similar experiences in our lives. When we muse about a whole group of such events, this pleasant emotion can give way to a prolonged mood of contentment sometimes called happiness. In such situations, the affect program, triggered continuously, provides a stable experience of stimulus decrease. There are those who, like the Puritans, avoid joy in fear that an unguarded moment might lead to danger (Leites 1986).

Can there be a disorder of this mood? Perhaps one such situation involves the type of drugs known as euphoriants, narcotics that can give one an experience of no feeling, which is interpreted by the individual as pleasant because it triggers contentment. Every drug user I have interviewed has convinced me that nobody resorts to these substances unless already in the grip of a chronically unpleasant mood, for chemical reduction of stimulus level only works to relieve misery. If you take a euphoriant when you’re already in a good mood it will “bring you down” to an unpleasantly low level of mental activity. These drugs rarely produce a pleasant experience for someone with a normal range of affective freedom.

I have heard clinical anecdotes about people in whom a chronic state of euphoria was traced to a brain tumor. Although most patients with multiple sclerosis are depressed, some will exhibit a degree of happiness singularly inappropriate for the extent of their neurological damage, which is probably due to the destruction of specific groups of brain cells. But by and large I think that disorders of mood characterized by steady and continued decreases in the intensity of stimuli must be quite rare, if only because there is a finite limit to the amount to which neural firing within the brain can decrease and life continue. We joke about feeling so calm that we might slip into coma, but I do not think such a thing really happens.

What about such common emotion labels as happiness and elation? Once again, it is almost impossible to know what another person means when using these words. As far as I can tell, elation seems to be a pleasant mood that follows a period of unpleasant mood; this pleasant mood contains elements of excitement and contentment. There is nothing wrong with using such words, but unless we can get a look at the face of the person who claims to be happy or elated, it is difficult to know what affects are involved. This is the difference between a theory of emotion based on adult experience and one built from what seems to go on in the brain of the infant. Later on, when we start talking about the affect we call shame–humiliation, you will see why these distinctions are important. Nevertheless, what little we have now said about the positive affects is enough to derive a theory about the nature of pride.