FEELING BAD: THE NEGATIVE AFFECTS

Just as we are “wired” or “constructed” so that certain experiences are intrinsically pleasant our genetic programming causes us to develop into creatures who experience other stimulus conditions as inherently unpleasant. Our ability to govern and control our actions is influenced markedly by this fact of life. We seek out the pleasant and avoid the unpleasant. The innate affects of fear–terror, distress–anguish, and anger–rage are produced by yet another group of stimulus conditions. These three affects are alike in that they are responses to what we have earlier called “overmuch.” There are three types of overmuch, and three distinct affects triggered by these three distinct stimulus profiles.

FEAR–TERROR

Watch the face of an infant when too much seems to be going on at once, when information is pouring in to that central assembly system at a rate less than what is needed to produce surprise but greater than that optimal level capable of triggering interest. Quickly the baby begins to stare with fixed gaze at or just to the side of (a bit away from) whatever might be the source of the stimulus. All over the body individual hairs may begin to stand on end. While the face becomes cold, pale, sweaty, and uncharacteristically immobile, much more is going on inside. Fear will race the engine, speeding up pulse and respiration, amplifying attention and cognition at a fearful rate. Nearer the upper range of terror will appear additional somatic experiences, such as a gripping sensation in the chest. The more adult the individual, the more knowledge and experience are brought into play to become part of fearful thinking—yet always accompanied by the staring face of fear.

Where interest itself might trigger our memory of novelties past and enjoyment–joy remind us of contentments past, fear brings reminiscences of frightening scenes, which cascade upon our consciousness at a rate guaranteed to produce increasing amounts of fear. Too many memories of too many dreadful situations may shift us from the discomfort of a scare to a direful mood, especially when some of these images represent unsolved terrors of the past.

The affect we call fear, which at its height might be seen as terror, is (like all affects) initially only a physiological reaction—in this case to a rapid increase in data acquisition. Growing and developing, we fill a storage bin with remembered incidents of fear and their triggers. This process will both shape and color the emotion each of us calls fear—and it will make the experience of fear quite different for each of us.

You will notice that so far I have avoided the word anxiety, the form of fear most important in current texts of psychiatry and psychology. Freud thought it important to distinguish between the fear triggered by an external event and that produced by something kept hidden from conscious awareness. When we knew the source, Freud called it fear, but when the source was unknown, fear became anxiety. Nearly a century later this distinction seems a bit antique, for it is unlikely that the process of evolution has given us different mechanisms to produce the same experience. Yet Freud was right to call our attention to the existence of the unconscious, to focus us on the mental world pushed out of awareness by mechanisms his genius revealed with clarity.

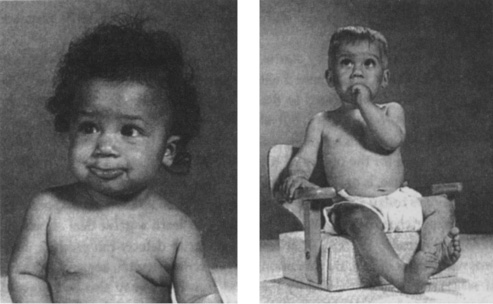

Figs. 6.1. and 6.2. Note the fixed stare and the frozen face of fear–terror.

At the level of innate affect it does not matter what triggered fear—all fearful emotion is at its core merely fear. Nevertheless, in psychoanalysis it is correct, even essential, to learn the relation between anxiety and the unconscious. I mentioned earlier that we can no longer use anxiety as the family name for all negative affects. In this book we will use it to represent the specific group of emotions in which the affect fear is triggered by a source whose origin lies in that portion of our memory kept hidden from us by a number of mechanisms.

There are so many marvelous expressions that capture the essence of anxiety. In Elizabethan prose a character might describe a sudden burst of anxiety with the expression, “Someone is walking on my grave.” I think that phrase describes the following sequence: (1) Some thought or memory peeps out from its hiding place in the unconscious, probably brought forth as an association to whatever was going on at the moment; (2) because of its intrinsic nature, this thought triggers the affect fear; (3) since the source of the fear is invisible to the individual, the memory bank is consulted to see if it contains any previous experience known to be capable of producing that type and degree of fear; (4) no real experience being found, the fear is declared equivalent to the colorful, fantasized situation then described.

In other eras this type of fear has been called “the heebie jeebies” or “the willies.” Always it is described with a sense of mystery because its source is occult.

When fear is preceded by startle, we say we were “scared by” whatever surprised us. When fear is mixed with shame, we are “caught unawares.” We can be frightened stiff, scared to death, aghast, panic-stricken, terrorized, apprehensive, timorous, or leery. But all of these emotions or attitudes bear some relation to the innate affect fear, assembled with its triggering experience in ways that make for the poetry of emotional life.

Panic, of course, is only another name for fear, and what are popularly called panic disorders today are nothing more than biological illnesses predisposing us to the experience of fear. We are beginning to learn a great deal about the biological circuitry for fear, or at least what circuit defects can produce inappropriate bursts of fear. As I mentioned in an earlier chapter, some of the sites of action normally stimulated by the affect fear-terror may also be triggered when our blood contains too much thyroid hormone, too much caffeine, or too much of the nasal decongestant pseudoephedrine.

It is fascinating that whenever these sites of action are triggered in a pattern resembling an innate affect, the brain assesses this pattern of responses as if it really had been caused by an innate affect. After all, since infancy we have been exposed to the patterns of muscular contraction, circulatory changes, odors, postures, and noises associated with innate affect, and we have learned to associate certain mental phenomena (which we call our feelings or our emotions) with those patterns. We have no such precedent for nasal decongestants. There is no intrinsic, prewritten script or program associated with hyperthyroidism, one that allows us to recognize it as such when it occurs. So biological malfunctions that affect any of the same sites of action that are triggered during innate affect can only be “understood” by us as peculiar episodes of ordinary innate affect.

This aspect of mental function is what we call pattern matching, and it is apparently one of the earliest attributes of the human brain. It seems that one of the basic characteristics of brain function is this activity of comparing current experience to the stored representations of previous experience. Time and again, in our study of human emotion, we run into this phenomenon. Everything that goes on, everything we do (or see, or remember, or in any way experience), is compared to what has been amassed as memory. Imagine how difficult would be our path through life were every situation always to be novel! The ability to compare immediate experience to past experience is the basis of all learning.

One of the great gifts brought by the psychoanalytic movement is the understanding that when people seem unable to learn from their experience one should consider the possibility that something has gone wrong with this mechanism of comparison. Empirically, it turns out that some life events accumulate too much negative affect. When even the memory of such an event brings with it a surfeit of unpleasant emotion, the event can be forced out of awareness by a group of mental mechanisms. By the time we reach adulthood we have accumulated enough such hidden uncomfortable memories and ideas that we give their warehouse a special name—”the unconscious.”

Since what is kept in this treasury is not available for normal business, it cannot be accessed for normal learning. As Freud taught us, some of it may leak out in dreams or those peculiar errors called “slips of the tongue.” But for general purposes, what has been restricted to the world of the unconscious is unavailable for the work of healthy comparison or pattern matching. Thus we believe that those who seem unable to learn from their experiences, to use failure or success as a guide to future behavior, may be blocked by their inability to make reference to certain memories that have been kept hidden within the unconscious. Part of psychoanalytic therapy or psychodynamic treatment is to use the special tools of psychoanalysis to investigate what is held as unconscious and to reduce the amount of negative affect bound with it. There are lots of ways to diminish the family of emotions called anxiety.

Yet recall the experience of fear described by people unprepared for the “side effects” of substances like the commonly available nasal decongestant I have mentioned so often. One of the concepts that will recur throughout this book derives from my observation of people in whom the emotion of the moment was triggered neither by current nor past events, but by an aberration of biochemistry and physiology. Whenever someone complains that an emotion seems inappropriate to the lived moment, we must first identify the affect involved and then search for the source of the affect. The system works in both directions—events trigger the neurobiology of affect, and disturbances of neurobiology that resemble the biology of normal affect can make us think of the kind of event that normally triggers affect. Particularly is this true for fear and for the myriad ills that can mimic the experience of anxiety.

Occasionally we meet patients in whom many or all of the sites of action normally associated with fear have been stimulated, but who seem unable to recognize these patterns of activity as an affect. Somewhat concretely, they describe the pounding of the heart as if it could mean nothing other than an affliction of that organ, appearing in one emergency room after another until referred to a psychiatrist by cardiologists who have exhausted their entire stock of test procedures.

John C. Nemiah and Peter E. Sifneos described a group of patients who had no language for emotion, coining the term alexithymia.* In my experience, these people fail to organize the subtle patterns of activity seen at the various sites of action I have described as associated with affect. They do not recognize its presence until affect reaches the upper limits of its range, at which time the heart does indeed pound as if it wished to leap from one’s chest, and thoughts of imminent death appear quite logical. Effective treatment often requires pharmacological suppression of extraordinary activity at these sites of action, and an intense, prolonged period of education leading to the recognition of affect as such. One critical characteristic of the patient with such forms of panic disorder is this inability to “know” the milder presentations of innate affect.

Nevertheless, no matter what quickens the pulse, pales the cheek, and arrests the freedom of gaze, it will be understood by us as some form of fear. It will be accompanied by an unpleasantly rapid increase in speed of thought and access to memory. And anybody looking at us will know we are afraid.

DISTRESS–ANGUISH

So far we have discussed only those situations in which the infant is programmed to respond to increases or decreases in the level of neural firing going on at any particular moment. Surely there must be periods of constancy, occasions when everything just goes along at the same speed. As you might guess, there are certain levels of stimulus density to which the affect system does not respond, levels which are acceptable to the system. This corresponds to those comfortable adult experiences we call periods of calm, moments in which a fair amount may be happening but with no augmentation by affect. So long sections of our day may be characterized by relatively constant levels of stimulus density accompanied by the phenomenon of no affect or very little affect. Not every moment is amplified by affect; not every moment is emotional.

The affect system contains a group of mechanisms responsive to a special range of such constant stimulus levels. What if some life situation immerses the infant in a batch of stimuli that remain constant but at a higher than optimal level? When the baby is cold, or hungry, or lonely, or wet, some organ of perception transmits data about these conditions to the central assembly system. For example, if the baby’s blanket falls off and the heat generated by its body is no longer kept within its tiny ecosystem, the temperature sensors of the infant’s skin report this as a constant stream of information. When this data stream is recognized by the central assembly system as a constant and higher than optimal level of stimulation, an affect is triggered in which the corners of the mouth are pulled downward, the eyebrows arched upward, and the infant begins to cry with tears and rhythmic sobbing. Distress–anguish produces varying levels of sobbing or crying, an activity that in itself is a constant-density experience, and that calls to the attention of the organism and its caregiver that some constant stimulus demands attention.

What the caregiver witnesses and experiences is the infant’s display of distress, after which this adult will react in a variety of ways to its sobbing or crying. The experienced mother will look over at her child, checking to make sure it is not exposed and cold, and next pick it up by slipping her hand under its buttocks, which will tell her immediately whether the baby is wet. If a dry, warm baby quiets immediately on being picked up, distress had been triggered by loneliness; if not, the mother checks for signs of pain or hunger. In a couple of seconds the caregiver has, without “thinking” about it, checked for all the common causes of a constant and higher than optimal level of stimulus density. If these maneuvers don’t work, she will look for other sources of distress.

It does not matter what organ of perception has transmitted information to the central assembly system of the baby. Distress can be triggered by data from memory, from a drive, from perception, from cognition. The affect we call distress is completely neutral with respect to its trigger. Any constant and unpleasant stimulus will activate the constant and unpleasant affect of distress. All this has something to do with the remarkable ability of distress to infect others—the contagion of crying that can take over an infant nursery or drive mad the parents of an inconsolable child.

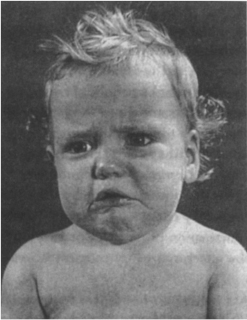

Fig. 6.3. Here is “the omega of melancholy”—corners of the lips pulled down in the unmistakable face of distress–anguish.

Anything that produces steady-state neural density within a certain range will make us feel like crying, and we can become distressed in a number of situations. We can sob, whimper, cry, or gulp for a moment when distress affect is triggered; and we can easily recognize it as a feeling. We can remember a couple of similar episodes and have the emotion of sadness, or our biography may contain so many tearful scenes that distressing memory can overwhelm and dominate our mood. One mood associated with distress is grief, a term that should be reserved only for prolonged periods of distress precipitated by the experience of personal loss. Grief requires distress, but not all distress is grief. Mourning and melancholy are other common moods involving the affect distress–anguish. There may be a great deal of distress in the wide variety of clinical conditions characterized by the “wastebasket term” depression, but depression is far more than distress.

By the way, since affect is independent of its source, anything that can cause even a minor degree of constant-density experience is capable of being added together with one or more low-grade stimuli that, when taken together, finally achieve the level necessary to trigger distress. We can handle a certain number of minor annoyances, but when the group of aches and pains that get to make up our day becomes large enough, we can unaccountably feel like crying. This is why the sort of thing that would never bother you on a good day is capable of driving you crazy when you are mildly ill. It probably is part of the reason women are more likely to cry when they are premenstrual. Some alteration of hormones, some change in the biochemical environment of the brain, may be producing the equivalent of a steady-state stimulus or decreasing the threshold for distress; with the addition of some “minor” pressure we can cry. Much that people call “stress” or being “stressed out” is the affect distress either in pure form or with a little bit of the affect fear thrown in for good measure.

Many of us slightly obese chronic overachievers eat when we are more tired than hungry. Just like hunger, fatigue is also a steady-state noxious stimulus. If we are the driven sort of personality that must ignore or disavow exhaustion in order to conclude what we declare to be the “more important” business of the day, we will pretend we are not tired. Since the trick of disavowal has prevented us from knowing” that we are sleepy, we search for another common source of distress. The result is a culture of adiposity—paradoxically linked with our culture-wide embarrassment that we are not modishly slim—and our energetic attempts to lose weight.

Why don’t adults cry as much as infants? Indeed, why are children so much more “emotional” than adults? In the case of distress we can see how social training alters and perhaps suppresses the expression of innate affect. Children learn very early that it is childish to cry—those who cry are babies. If you want to humiliate a child into not crying, you need merely call him or her a crybaby. The British tradition of the “stiff upper lip” is related to this system of affect control. The first thing that happens when distress is initiated is that the comers of both lips are drawn downward. But the act of crying is preceded by a wrinkling and trembling of the upper lip, which itself then becomes a constant density stimulus. Training a child to focus on the upper lip distracts attention away from the experience of distress, and any interference with the affect decreases its ability to create more distress. Throughout our lives we are encouraged to do nearly anything that will prevent us from crying in public.

“TEARS OF JOY”

I should mention one other situation in which people cry. Most of us have been embarrassed to find ourselves crying at weddings or other similarly happy events. There used to be a series of television advertisements for a popular brand of instant coffee in which a happy or loving scene (usually involving the resolution of loneliness) was assembled with information suggesting that the coffee tasted good. (“Times like these were meant for Taster’s Choice.”) Many, many people cried during these commercials, weeping in response to the deeply moving interpersonal scenes. I don’t know whether they sold a lot of coffee, but they sure affected people! Yet had you observed their faces as they reached for a handkerchief to dab a suddenly moist eye, you would have seen no other evidence of distress. Tearing was independent of the facial display of distress—no downturned mouth, no wrinkled and trembling upper lip.

Tomkins believes that in this very special case tears are triggered by the sheer density of memory brought to mind by the event being witnessed. In the case of the Taster’s Choice commercials, the scenes depicted by the advertiser are assessed by the central assembly system on the basis of their resemblance to our lifetime of powerfully affecting experiences of loneliness and coming together, of love lost and love redeemed, of social failure and healing success. The utter volume of such data suddenly brought into awareness is thought to be another specific trigger for tearing. In a letter to me, Basch referred to it as a form of “emotional sweating.” I believe that the human capacity for the storage and retrieval of memory has evolved more rapidly than has the integration of this power with the subcortical mechanisms that produce affect.

Recently, Mike Schmidt, Philadelphia’s lone baseball hero, retired after a generation of literally spectacular athletic achievement. Like Julius Erving, the superstar of the Philadelphia basketball team who had retired not long before, Schmidt decided to quit not when he was no longer able to play, but rather when his body could no longer allow him to work at a world-class level of performance. As befitting his stature within the world of sport, he announced this decision at a press conference—before an immense assembly of reporters, microphones, and cameras. Doubtless what he had planned to say was clear, cogent, and pithy, well in keeping with his character. “I felt lucky enough just to be able to make it into the major leagues,” he said, continuing as if to say what it had meant to him to have played so well for so long. Yet he was “overwhelmed with emotion” and nearly unable to speak for the tears that welled up. Embarrassed by this “lack of self-control,” Schmidt turned away and terminated the conference.

This sequence of events can be observed no matter whether the triggering scenes are pleasant or unpleasant. (Those of us who cry at weddings are rarely experiencing true sadness. And I doubt that the newly crowned Miss America is sad when, each year, she bursts into tears on learning of her victory.) As is typical of all situations involving innate affect, there does not seem to be any connection between the quality or meaning of the stimulus and the affective response. I suppose that this should be given the status of another innate affect, but the situation is uncommon enough that it is considered to be an oddity of the affect system. It makes sense, though. The bodily mechanisms that can be taken over by innate affect range from the involuntary to the voluntary systems. We are used to the fact that tearing (which certainly must have evolved as a method of protecting the eyes from physical danger) can be taken over by distress. So, at least until a better answer comes along, I suspect that we can accept Tomkins’s answer for the puzzle that in certain peculiar situations our eyes leak tears when we are not sad.

In the final chapters of this book I suggest some of the reasons modem life has become so complex, and, for many, so overwhelming. Evolution has “conferred” on us the ability to store and retrieve memories with a facility impossible for prior life forms. With such structural potential comes the proclivity for avalanche. Only of the human can it be said that memory is capable of over-loading our circuitry. The enormous amount of information made available to us by so many channels of data acquisition, as well as the huge and growing number of ways that the activities, interests, and accomplishments of individual humans can be brought into public consciousness, all encourage the likelihood for overload. The tearful response to such overload may very well be a major affective experience for the humans of our future.

ANGER–RAGE

A man stands in front of me at an airline counter. Nothing he can do will affect the inalterable rules of the airline. By his side is a package a few inches too tall to be brought on board as carry-on luggage and containing porcelain too delicate to be placed in the baggage hold where it will be thumped, bumped, and tumbled until it is returned to him. I observe the man, whose face is red, whose whole body is shaking with increasing intensity, and who begins to pound the ticket counter with his tightly clenched fist. His voice begins to rise in volume, as if the reason he is not being heard is that people cannot hear him.

Having checked in and received my boarding pass, I grab a bite of food at an airport restaurant. Ordering a meal and a bottle of wine at the table to my left is a young woman. Although she is smiling as she gives her order, everything about her seems tight. The hand clutching her menu is white-knuckled. When she pauses to listen to the waitress I can see from the rhythmic bulging of her cheek muscles that she is clenching and unclenching her jaw. She taps her foot impatiently while waiting for service. As luck would have it, the food that finally arrives is unacceptable, and she explodes in rage, denouncing the waitress, the airport, and the city she is leaving.

So many things can make us angry, and so many things can happen when we get angry. One problem for the student of emotion is that people vary so much in their expression of anger. Early in my career as a psychiatrist I saw a great many people for diagnostic evaluation. Disappointed with what I had been taught, I developed a new kind of standardized interview that allowed me to figure out not only what was wrong but what needed to be done next. I ask a lot of questions that will tell me how this stranger experiences each of the innate affects. Especially am I interested in the way he or she handles anger and the way each parent behaved when angry. Having now interviewed over a thousand adults, I have learned a great deal about the expression of anger.

Some people are never angry. Others are always angry. Some people explode like a summer thunderstorm—raging for moments and sunny thereafter. Others simmer and burn for hours. Some yell or hit, others clam up and withdraw. Some will never forgive, others forget immediately. Each of these people is experiencing the same affect, assembled in ways developed over a lifetime, magnified or damped by virtue of their having grown up in a particular family, neighborhood, and era—and, despite all these differences, perceived by them as real anger. Naturally, when I tell them about the ways other people get angry, they act surprised that anybody would behave in such a manner.

If we are going to understand anger, we had better return to our study of the newborn and ask how and where anger fits into the affect theory we have been discussing. Is there a red thread that connects everything we know about anger?

Everybody knows that a crying infant can become a screaming infant. Sobs of distress give way to the face of rage—the clenched jaw, furrowed brow, reddened cheek, and scream of anger. Why? How can an infant “know” what to be angry about? Tomkins draws an analogy to our understanding of the affects discussed above.

Just as certain low, steady levels of stimulus density are acceptable to the system and do not trigger any affect, and other steady-state but higher than optimal levels of stimulus density trigger distress–anguish, there is an even higher range of steady-state stimulus density that triggers the innate affect we call anger–rage. Again, the innate affect is not a state in which the organism is angry at somebody or angry about something. It is merely a state in which the affect anger is expressed because the program for it has been activated.

The affect anger is another of those circumstances in which we are dealing initially with quantities of stimulation, with what might on an oscilloscope screen be seen as the number and the height of little green blips. And these little green blips achieve a pattern that is recognized by a system that does not “care” what they “mean,” and which then sets in motion a series of events that becomes for us the qualitative experience we call anger. This is the implacable logic of the affect system. The newborn infant, squalling and raging on its changing table, fists and feet clenched, jaw alternately clenched and screaming, brow intensely furrowed—this infant does not know that it is angry and does not know what made it angry. “All” that has happened is that some group of stimuli has achieved a level of density adequate to trigger anger. Stated another way, some noxious steady-state stimulus has triggered an affect that tenses the muscles of the face and other parts of the body in a manner analogous to this triggering stimulus.

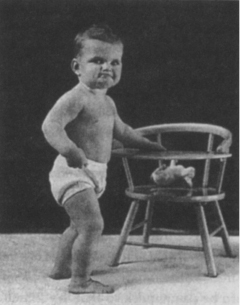

Fig. 6.4. Mouth and chin tight, eyes narrowed legs planted firmly, right hand about to make a fist—this is the isometric muscularity of anger–rage at the milder end of its spectrum.

Once you get the idea that anger in the infant is associated with muscular contraction and an intensification of all activity, you can see fascinating variants of the affect. A friend asked me to observe her infant, saying that she was frightened by one of his gestures. Whenever this two-month-old boy was unable to get what he wanted, he would clasp his hands and push them against each other as hard and as steadily as he could. Within a few moments his face and upper body became red with effort, and quickly enough the entire picture of anger-rage had been triggered. It was a perfect example of Tomkins’s observation that autosimulation of innate affect is one of the earliest realms of learning. I suspect that, having learned the association of anger and muscular contraction, he now knew how to make himself angry when he wanted to, to amplify intentionally whatever degree of anger he was then experiencing. He looked for all the world like someone practicing isometric exercises. I wondered whether that had anything to do with my observation that so many chronically angry people seem to be extremely strong.

Infants learn quickly. Just as we group by the pattern of their occurrence all the situations in which we have become excited or all the situations in which we cried, we begin to group the situations in which we became angry. From the massing of such memories comes our understanding of what it means to be angry. And from such experiences each of us develops our own private emotion, what we as individuals know as “our” anger.

Like all affects, anger calls to the attention of the organism and to its caregiver that something needs to change in order for the infant to be released from its discomfort. In the case of anger, the affect system says that change has to be damn quick so that the stimulus density will be reduced enough for the child to recover its composure. Anger, in the language of the psychologist, is instrumental. It makes things happen. Anger, with its tremendous expenditure of energy, can be the instrument of change.

Dr. Joseph Lichtenberg,† a psychoanalyst who studies child behavior, asked me to “watch a nine-month-old child pushing a toy around the room. He gets to a point where the toy won’t budge, and after pushing it for a little while, he gets angry at it and gives it a whack. Suddenly the toy goes flying. Now the child goes around the room happily whacking the toy.” Anger, which had perhaps in this instance been an affective response to the child’s experience of futility, turned out to provide the needed change in technique. Anger had taught the child just how much force and what kind of force was required to move the toy past an obstacle. The affect became the instrument of change. You can see something like this operating in the theater of professional sports, where anger and intensity of play often run hand in hand.

You will recall that one of the major features of the affect system is that, once it is triggered, each innate affect exerts its influence on any bodily action occurring concurrently. This is what Tomkins calls the correlative action of affect—it imprints its pattern of action on whatever is linked to it. That helps explain why a whining child is so irritating to us. In whining, a child speaks with great intensity and draws out each syllable as long as possible. Whining is a perfect example of an activity influenced by an affect that is both a response to constant-density stimulus and an amplified analogue of this constant-density stimulus.

Anger communicates broadly and rapidly. Just by looking at someone who is angry we can tell a lot about what is going on inside. So vividly does anger communicate that we learn to mask its display in order to retain some sense of privacy when we are angry. In some people the display of anger becomes so refined and contained that only tiny remnants remain, like the bulging jaw muscles or whitened knuckles of the woman I described a moment ago. Once I saw in consultation a young lawyer who professed to be the least angry of men. We smiled pleasantly at each other as we discussed both his needs and his biography. Later, when I thought that by my attentiveness I had earned enough of his respect for him to be willing to look at something he had not expected, I asked this calm, pleasant man to glance over at his right hand, which was clenched in as tight a fist as I had ever seen. “Huh. What d’ya know?” he said. “I’m angry.”

Nowadays most American cities have strict rules about when one is allowed to use an automobile horn. When you toot the horn in one or two short bursts you have activated the resetting affect of surprise–startle. But when you “lean” on the horn, maintaining its noise for a prolonged period of time, you have mimicked the profile of anger–rage, which indeed gets the attention of others but is capable of getting them quite angry. You might think of the ordinances that prohibit promiscuous horn honking as a public health measure aimed at the modulation of the affect anger–rage. In normal interpersonal life the most prominent stimulus to anger is humiliation. What makes the slings and arrows of everyday life into fortune that we find outrageous is some as-yet-unexplained link between shame and anger.

Anger as affect can be the fleeting tension of a moment, or it can be recognized as an angry feeling. To the extent that any particular episode of anger recalls to mind previous similar experiences, we are experiencing anger as an emotion. Too many angry thoughts about too many issues left too long unsolved can produce an angry mood capable of lasting until something brings relief. I have seen patients with brain tumors whose raging anger always seemed inappropriate to the situation at hand, and there are many documented cases of people in whom attacks of rage are caused by the kind of electrical discharge called an epileptic seizure. Cocaine and the amphetamines can arouse people to states of rage. Everybody who has any degree of manic-depressive illness is likely to have attacks of rage secondary to this biochemical condition, and the intensity of these bursts or periods of rage are a good measure of the seriousness of the illness itself. I cite these examples to remind you that the affect anger–rage can be seen as affect, feeling, emotion, mood, and disorder. We all have to deal with angry people from time to time, and it helps to know both the source and the meaning of their anger.

*See Nemiah et al. (1976) for a brief review of this fascinating concept.

†Lichtenberg’s text (1983) was the first to join the disciplines of infant observation and psycho-analysis.