EMPATHY: AFFECTIVE RESONANCE AND THE EMPATHIC WALL

Just for a moment, let’s go back to watching babies. Sneak a look at a little person who doesn’t know you’re there. Watch how a baby brightens when looking at its crib mobile, reaching out to touch it, laughing in delight at its colors or at the feel of the brightly colored wood or plastic. As long as the mobile holds its interest, which can be a matter of seconds, the baby’s face is alive and shining with interest and enjoyment. When no longer involved the baby may grow quiet, its face reflecting the neutral state of no affect. Should a small noise startle it to full attention, we would see the next series of affective responses to whatever stimuli are perceived or experienced. The qualities we call “alertness” or “aliveness” seem to be due to the innate affects of interest and enjoyment that are triggered in the normal course of the infant’s day.

Although most people are fascinated by babies and charmed by their facial expressions (even though they may not know the relation between these movements, colors, or vocalizations and their origin in innate affect display), it is happy babies we like best. There are many reasons for this commonplace observation. The positive affects of interest–excitement and enjoyment–joy are so intrinsically rewarding that when we see an infant express them we are drawn into an interaction because happy babies make us feel good. Similarly, the basic wiring pattern of the human, the circuit design of the affect system, makes babies and adults alike enjoy the experience of sharing positive affect.

I have mentioned that each of these innate mechanisms becomes a powerful communication device. A baby in the throes of an affect is a broadcaster of affect, and we observers resonate with their transmission. The contagious quality of broadcast affect literally drags the observer into resonance. The intensity or effectiveness of this broadcast is decreased to the extent that this organism learns to modulate the display of innate affect. Babies, with their nearly pure, unmodulated display, are the most powerful broadcasters and the most compelling partners in affective interaction or “conversation.”

This is, of course, the physiological basis for what later will be called empathy, the sharing of emotion that accounts for much of the quality of adult interpersonal relationships. Around strangers we control our affective display more than with our intimate friends—we share our feelings in proportion to how safe we feel in the company of another. Nevertheless, we are lightning-quick to sense minuscule variations in the degree of resonance, the “fit” between ourselves and the other. This learned, adult achievement—the ability to exhibit affect over a wide range of display, from the most subtle and sophisticated to the most broad and infantile—allows us a wide variety of styles of interpersonal behavior. We “know” when it is permissible to “let it all hang out” or when we must be “contained.” Social awareness makes us take care to vary the extent to which we ask the other to handle our affective output.

I keep repeating that each affect is analogous to whatever has triggered it. Fear, which is triggered by an unpleasant cascade of data, makes that experience even more unpleasant when affect and source are joined; the calming affect of enjoyment–joy reduces brain activity in a manner parallel to what has triggered it; distress makes us more distressed because it is a constant-density experience quite capable of triggering further distress; and so on. As I have mentioned, Tomkins feels that it is from our awareness of the way the skin and muscles of the face have been “rearranged” or “distorted” by the affect as it “hits” us that we figure out what we are feeling. Most likely a host of tiny alterations in the microcirculation of the face increases the sensitivity of other receptors that in turn carry still more information back to the brain. These facial displays are capable of changing rapidly—some of them in tenths or hundredths of a second—and our awareness of what we feel is also capable of such rapid shifts.

Since such a significant portion of each affect is expressed as external display (always on the face but also over the entire body), the affects are as much social phenomena as they are internal experiences. Anyone who is “tuned in” to someone with a visible display of innate affect is looking at a face that has been “arranged” by the contraction and relaxation of specific groups of voluntary muscles. To the extent that we are willing to mimic the operation of these muscle groups, we can share the affect just triggered in the other person.

It does not matter whether the face we imitate is one projected on the giant silver screen of the motion picture theater, or our beloved beside us, or the newborn infant cradled in our arms. Whatever the source of the affect we imitate purposively or the contagion we accept passively, it becomes the source of the affect we now experience. This is the basis of empathy, the sharing of emotion that makes for so much of the pleasure of social experience.

Basch (1983a)* has pointed out that there are a number of separate steps in this process of empathic linkage. First, of course, we resonate with each other’s affective broadcast. Next, simply because we have agreed to experience an affect broadcast by someone else, we begin to recall previous experiences of that affect, just as if it had been triggered by some experience unrelated to other people. Now we begin to form an emotion in the sense Basch has described—the assemblage of this affect (which we have just received from someone else) and our associations to our own previous experiences of that affect. For this reason, empathy is nothing like what happens when two computers are wired together. Whereas each of us shares the identical vocabulary of nine innate affects, we differ so greatly on the basis of our life experience that what we think and feel during the period of empathic connection is similar, but actually quite different.

Fig. 7.1. Faces, hands, and posture all suggest the affects fear–terror and distress–anguish; the lassitude with which these people are painted suggests also that they may be in an early stage of depersonalization as a defense against intense negative affect. Yet artist George Tooker titled his painting “Birdwatchers,” leading us to expect the positive affects of interest–excitement and enjoyment–joy, therefore setting up a disturbing oscillation between what we feel through affective resonance and what we read.

People who are in tune with each other live in a fellowship of feeling. Yet this phenomenon, which I think of as affective resonance, is not always so pleasant an occurrence. Resonating to the broadcast of affect from a demagogue, we can become members of a mob. Taken in by the false display of affection that draws us into the confidence of a scoundrel, we can be fleeced of our earnings or seduced in a way “better judgment” might have prevented.

Affective resonance is so powerful, so distracting a system of interaction, that infancy is the only period of our lives during which we are allowed free range of affective expression. In every society on the planet, children are speedily taught how to mute the display of affect so that they do not take over every situation in which they cry, smile, or become excited.

Many years ago I heard a famous entertainer say that she didn’t mind hecklers or even a hostile audience now and then—that was a fair challenge to her. “But,” she told us, “never try to work a room with any kid under three. You can’t compete with a baby.” She knew that the pure and unmodulated expressions of affect transmitted by babies were capable of distracting the most attentive audience. It is okay for mommy and baby to be locked in an interaction based on the interplay of innate affect, but society demands that these interactions become increasingly private as we grow up.

Just as most or all of the affect we broadcast into our environment must be limited by social or cultural forces, we adults are also obliged to learn a number of skills to help us manage the affect broadcast by others. Imagine how difficult it would be to keep your mind on whatever interested you if you were forced to resonate with every burst of affect that came your way from someone else. Suppose, by way of analogy, that no one thought privately about anything, that humans were only capable of talking aloud instead of “thinking.” Privacy would depend on our ability to develop some kind of adaptive deafness.

Science fiction writers have tackled this sort of problem in their speculations about telepathy. If all our mental processes were broadcast into the space that surrounds us and experienced with clarity by our neighbors just as by ourselves, we would live not as individuals but as some sort of communal being—unless we developed some way of shielding our thoughts. Our whole concept of ourselves as private individuals is based on the idea that we can be alone, free from the intrusion of others, just as our concept of society is based on the idea that we can communicate with others. Adult life as we know it requires some balance between privacy and communion.

There are two reasons we do not walk around constantly being taken over by the affective experience of others. On the one hand, as I noted a moment ago, social form dictates that with maturity we will learn to express very little affect. Somewhere around the age of three we learn to trade the powerful language of affect for the more specific but far less compelling language of words and sentences. Affect is damped, suppressed, blocked, by social convention. Our whole concept of what it means to be mature is based on the expectation that adults can “control themselves.” Control of affective expression reduces the amount of affect broadcast into the interpersonal environment. It makes life easier for those around us.

This contagious quality of affect is so powerful that the normal adult has built a shield for protection from the affective experience of the other person, a mechanism I call the empathic wall. It is a skill, a learned mechanism by which we can tune out the affect display of others. One way of building an empathic wall would be by refusing to mimic the facial or bodily display of affect we see in other people, but there are other ways this can be accomplished, other places to block in the circuitry for the interpretation of innate affect.

One might, for instance, learn to recognize the feeling of contagion, learn to sense the very moment that another person’s affect begins to tickle our own receptors. Then we might decide to shift our attention to something else, to manipulate the central assembly system and stop the process of resonance. We can block completely the experience of affective resonance by this mechanism of distraction, or we can limit it over carefully graduated levels of connectedness.

Men, especially, will recognize this as the system most of us use to avoid being taken over prematurely by the sexual excitement of our partners during intercourse. Part of the skill required of a man for effective partnership in sexual intercourse is the ability to monitor his partner’s level of arousal. Through experience we learn to recognize the degree of her readiness for orgasm. When we sense that she is on the brink, we allow ourselves full resonance with her excitement, which moves us to the level of excitement and arousal that will trigger our own release. In well-matched couples, a woman will use (join with) this last increment in his broadcast excitement as an amplifier of her own, and the couple can share the pleasure of each other’s orgasm. Often the treatment of premature ejaculation involves little more than training in the modulation of affective resonance—shoring up the empathic wall.

It is this empathic wall that allows us to maintain our own boundaries in the presence of other people when they are experiencing or displaying affect. The empathic wall helps preserve the unity of the self. Adults who do not learn how to shield themselves from the emotional life of others suffer greatly because they fail to develop a secure identity, just as those who are overly “immune” to the affects of others suffer in the closet of emotional isolation. If the empathic wall is too rigid, we will be immune to the feelings of others; if too flimsy, we will tend to be taken over by powerful feelings broadcast from outside ourselves.

In general, then, we adults have learned to mute our own affect display so that we are acceptable to the society in which we live, to shield ourselves from the affect display of others, and to rely on the relatively drab and colorless transmission of data by verbal language. One implication of this developmental tendency is that most adults have to “learn” how to communicate with babies or to become “sensitive” to the feelings of their fellows. Most likely mothers learn to adjust to the affect display of their infants by giving up the empathic wall, by agreeing to allow themselves to be taken over. Doing this, of course, they achieve a degree of connectedness with their babies that is a major part of the complex group of emotions we call love. Despite the importance to each of us of finding a relationship in which our worst feelings are tolerated or accepted, for the vast, overwhelming majority of humans the experience of love implies mutual permission to share the positive affects of excitement and joy. The absence of love is experienced as lonely for those who enjoy such communion.

When we study that remarkable phenomenon called “good mothering,” we notice over and over again the caregiver’s ability to “tune in” on the affect display of her child. In recent years there has been much research on the transactions of “affective attunement,” and many scholars are now providing empirical evidence for the interactions between mother and infant that Tomkins described in detail nearly 30 years ago.

So special is the appearance of a healthy system for the reception and interpretation of innate affect that we tend to think of anybody with this kind of sensitivity as gifted. Mothers, therapists, novelists, actors, and confidence men are usually successful to the degree that they are empathic. Perhaps the reason it has taken so long for our civilization to understand the nature of the affect system is that each of us has grown up working hard to avoid and control our own affects.

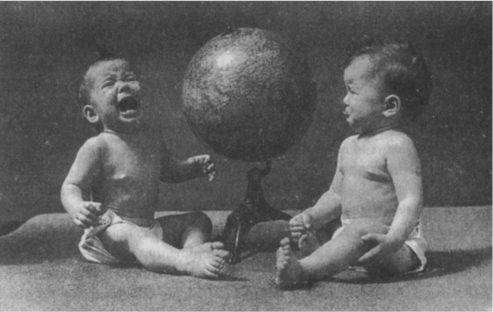

Fig. 7.2. No empathic wall here! The child on the left demonstrates distress–anguish at the upper end of its scale. Gazing directly at the face of his unhappy companion, the child on the right has begun to resonate with this broadcast affect and shows mild distress.

This is particularly important in the case of the affect distress–anguish, for we adults vary considerably in our attitude toward crying. Every once in a while, in every city, in perhaps every era of recorded history, the murder of an infant can be traced to the mechanism of unwanted and unbearable affective resonance. The stories are all pretty much the same. Recently, here in Philadelphia, a young mother told her husband she couldn’t stand the constant crying of her baby, which made her feel like screaming. One day, when the husband called to check in, the mother announced that she had drowned the baby in the bathtub to stop its crying. More often it is the father who kills a baby in such situations, but always the clearly stated reason for the murder is this inability of one parent to handle the constant and inalterable experience of an infant’s unmodulated anguish.

That such tragedies are rare speaks for the general observation that by and large people learn to modulate their own affects and to develop the interpersonal affect management system I call the empathic wall. That they can occur at all forces us to acknowledge the power and the nature and the inherent contagiousness of innate affect.

There are, of course, other family situations made unbearable by the presence of unmodulated affect—all characterized by manifest discomfort on the part of the receiver. Although alcohol can act as a calmative agent, many of those who are addicted to it drink until they become quite explosive. Children forced to live in the midst of such affective explosions are often deeply scarred by them. There is a wide variety of clinical syndromes produced by parental affective excess, among which are patterns of personality development characterized by literal terror of high-density affect. As adults, some who have grown up in such families tend to suppress the display of affect in themselves and in their children, to act as if they were allergic to affect itself. This strategy produces offspring with a limited experience of affect modulation, thus predisposing to the use of alcohol (as well as other drugs and diversions) as a modulation device (with the same pattern of noxious effects that started the cycle) or an explosive personality with no relation to alcohol.

The clinical disorder of alcoholism is extraordinarily varied in its presentation, and only a small fraction of alcoholic families develops in this manner. All dysfunctional families are islands, clusters of people with immense walls protecting one or another horrible system of affect modulation, walls that prevent the intrusion of other systems of modulation. The walls are meant to protect the protagonists from the shame of exposure to the outside; actually they immure the family illness.

Recently, on the basis of anecdotal evidence, it has become the fashion to claim that all dysfunctional families share the relation to affect modulation described above—and to claim that the cause lies in the use of alcohol rather than anything to do with affect. The benefit of this therapeutic maneuver has been to allow an immense number of people to group themselves into a supraordinate family within which they can feel a previously unavailable kinship. Unfortunately, in order to take advantage of the love and succor offered by these systems of group treatment, many lonely and distressed adults have been encouraged to redefine their histories in the language of this one specific theme.

There are lots of reasons for violence within the family, for manifest failure of affect modulation. Although shame plays an important role in every aspect of this dysfunction, no treatment method can be effective until it has been placed within a complete understanding of all affect. Even though it is the basis of all empathy, affective resonance can be torture for those forced to live in a system they cannot handle.

It is precisely this ability of broadcast affect to take over consciousness that must call to our attention another of Tomkins’s major points: Consciousness itself is a function of affect! Only those bodily or mental activities that achieve affective amplification will realize the degree of significance that makes them conscious. It is only through its assembly with affect that anything becomes important enough to us that it can be called the focus of our attention. Even psychoanalytic exploration, which brings into consciousness long-buried thoughts and memories, is totally dependent on this relation between affect and awareness. The analytic therapist’s muted display of affect assists internal reflection by avoiding distraction. Meditation is a system through which we agree similarly to allow affective amplification of thoughts normally left out of awareness.

Broadcast affect can take us over just as surely as that derived from purely internal sources. It is difficult enough for us to pay attention to anything for more than a few moments at a time, simply because our associations to whatever is going on trigger affect that then turns attention to those more internal sources. This is why we so often have to ask people to repeat what they were saying only a moment earlier. We simply cannot “hear” what fails to garner affective amplification, just as we can only hear whatever is currently being amplified by affect.

Once I heard a radio interview with a Walt Disney Studio artist who had worked on Snow White, the first full-length feature film done entirely in cartoon. What surprised him most was the degree of audience response to the scene in which the seven dwarfs were huddled around Snow White’s funeral bier. “Everybody in the theater was weeping simply because we had drawn the backs of the dwarfs with a certain curve.” Anything that signifies innate affect is capable of breaking through the empathic wall and taking us over.

Have you ever encountered someone who smiles at you during a difficult discussion, nodding emphatically and constantly in order to draw you into agreement? Such people are attempting to trick us into positive affective resonance (and therefore agreement) so that we will disregard some potential source of negative affect. It is the adequacy of the empathic wall that protects us from such maneuvers.

*An excellent review of some earlier theories for empathy may be found in Max Scheler, 1954.