SHAME–HUMILIATION

There is good evidence to lead us to suspect that the physiological basis of the emotion shame is an inborn script that attenuates affects much in the same way that dissmell and disgust limit hunger. We believe that the affect Tomkins calls shame–humiliation is the inherent, internally programmed “innate attenuator circuit” for the positive affects. Since it is the mutualization of interest–excitement and enjoyment–joy that powers sociality, shame affect is therefore an innate modulator of affective communication. Just as dissmell and disgust are auxiliaries to a drive, mechanisms that have evolved to the status of affects, shame–humiliation is an auxiliary to the affects, one that has achieved a status equal to its predecessors.

Recall, asks Tomkins, all those times you have seen an old friend at a distance and waved vigorously to get his or her attention. When that other person gives us the smiling face of recognition we are rewarded by a surge of pleasure. But occasionally it turns out that we had hailed a stranger, having been fooled by an unexpected resemblance.*

The moment we recognize our error something surprising happens to us. Although one might think all we need do is maintain our composure, nod politely, and ask this person to excuse the intrusion, before we can get the words out of our mouths something else has taken place. As soon as we have seen the face of the other person our own head droops, our eyes are cast down, and, blushing, we become briefly incapable of speech. Sometimes a hand goes unbidden to the mouth as if to prevent further communication, and we feel a surge of confusion. This series of events is one adult manifestation of the innate mechanism Tomkins calls shame–humiliation. Like all the innate affects, shame–humiliation seems to be a script, a series of events initiated when its button is pushed and terminated when the entire script has been played out.

Shame differs from all the other affects in at least one significant feature. It appears to be triggered neither by variations in the shape and intensity of nonspecific internal neural events (as in the case of the six basic affects) nor by the detection of specific noxious chemicals, as in the case of the attenuators dissmell and disgust. Shame–humiliation is an inborn script, an attenuator system that can be called into operation whenever there is an impediment to the expression of either positive affect. It depends on the remarkable ability of highly organized, advanced life forms to assemble the data of perception into patterns and to compare those patterns to whatever has been stored as memory. In certain situations, as, for instance, when a pattern mismatch is detected while we are in the midst of interest or enjoyment, the affect shame–humiliation attempts to reduce the affect that had held sway a moment before.

I know you are disappointed that I didn’t say anything that resembled in any way your own experience of embarrassment, humiliation, shame, mortification, ridicule, put-down, and so on. Just as when I described the difference between the affect enjoyment–joy and the enormous group of adult experiences z we lump together as “fun” or “a good time,” there is a world of difference between the meaning-free physiological mechanism Tomkins calls shame–humiliation and the highly meaningful adult assemblages that we know as our own personal emotions.

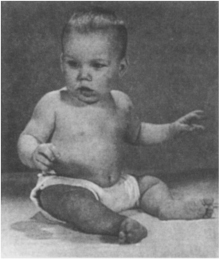

Fig. 10.1. Eyes averted and downcast, neck and shoulders beginning to slump. This is the purest presentation of the affect shame–humiliation.

Fig. 10.2. Here shame interferes with this baby’s ability to remain interested in the toy. Was the kiss intended to pull the baby out of its slump, or was it the trigger for shame–humiliation?

Trust me. There had to be a good reason that I asked you to learn the entire affect system before presenting the concept of shame. It is the most recent affect to develop through the process of evolution, with the possible exception of the tears leaked when we are “overwhelmed by emotion.” Shame requires the presence of other affects. Shame exists only in terms of other affects.

Let’s go back to review the positive affects interest–excitement and enjoyment–joy for a moment. Interest–excitement is a response to an optimal in crease in neural firing, a program triggered when a certain gradient of increase is sensed by the affect system. Interest itself is an intrinsically pleasant amplification of its stimulus. It makes us more interested in whatever is going on, more avid for whatever experience triggered it. Interest has a characteristic feel. We have experienced interest since birth. We know what it feels like, we know to a fare-thee-well every nuance of its rise and fall, its temporal profile.

|

Table 4 |

|

THE INNATE AFFECTS |

|

POSITIVE |

|

1. Interest–Excitement Eyebrows down, track, look, listen |

|

2. Enjoyment–Joy Smile, lips widened and out |

|

NEUTRAL |

|

3. Surprise–Startle Eyebrows up, eyes blink |

|

NEGATIVE |

|

4. Fear–Terror Frozen stare, face pale, cold, sweaty, hair erect |

|

5. Distress–Anguish Cry, rhythmic sobbing, arched eyebrows, mouth down |

|

6. Anger–Rage Frown, clenched jaw, red face |

|

7. Dissmell Upper lip raised, head pulled back |

|

8. Disgust Lower lip lowered and protruded, head forward and down |

|

9. Shame–Humiliation Eyes down, head down and averted, blush |

Enjoyment–joy is a response to any decrease in neural firing. It is a program triggered when a certain gradient of decrease is sensed by the affect system. Enjoyment itself is an intrinsically pleasant amplification of its stimulus. It makes us enjoy more whatever is going on by calming us pleasantly. Enjoyment–joy has a characteristic feel. We have experienced enjoyment–joy since birth. We know what it feels like, we know to a fare-thee-well every nuance of its rise and fall, its temporal profile.

But there are lots of times that something interferes with the operation of either of these intrinsically pleasant affect programs. For instance, take the situation where lovers are communing, sharing the interplay of interest and enjoyment. In such situations we are exquisitely sensitive to tiny alterations in the flow of affective resonance. Should our partner in love but for a moment decrease his or her degree of resonance, instantly there is a shift in the interpersonal field. This need be nothing more than a frown crossing the face of the other, or failure to smile when one said something intended as “funny” but which stimulates an unexpected memory and therefore an unexpected affect, or a slight alteration in the degree of relaxation taken for granted in the relationship. Where, a moment earlier, we could by all means expect a certain flow of affect expression, suddenly there is an impediment to this flow.

This concept of impediment is quite specific. It refers to anything that disturbs the normal, expected flow of the patterns for the positive affects interest or enjoyment. An impediment to positive affect is an interference with the pleasure of everyday life. Do you live in a home with a burglar alarm? Most likely it involves an ultrasonic system (something like radar) in which a signal is broadcast into the environment from one point and received and interpreted at another. Anything that interferes with the normal pattern of broadcast and reception will trigger an alarm mechanism. Affect is like that. We are so used to the normal ebb and flow of our interest and of our enjoyment that any interference with this well-known and oft-experienced sense of flow will be recognized immediately.

Naturally there must be occasions when an impediment to positive affect quite definitely turns off that preexisting state of excitement or enjoyment. One sunny summer afternoon, when my then six-year-old daughter and I were watching television together, the electricity for our neighborhood was knocked out by a local storm. The images that had so entranced her were suddenly replaced by a blank screen, and she screamed in terror. In this case the interruption of what had been maintaining the pleasant state of triggered interest and enjoyment, the interruption itself, had been so sudden as to trigger the affect surprise–startle, which then was followed by the affect fear-terror as she tried unsuccessfully to figure out what had happened to her friends—the characters on the television screen. In adults, such a sudden alteration in stimulus contour will also produce an immediate shift in attention despite our conscious and cognitive “wish” for that stimulus to continue.

The affect program for shame–humiliation is triggered in those common situations when an impediment occurs but whatever had been a competent stimulus for interest or enjoyment remains a competent stimulus for those affects. In other words, shame affect is a programmed response to an impediment to preexisting affect when there is every reason for that preexisting affect to continue! Shame affect is a highly painful mechanism that operates to pull the organism away from whatever might interest it or make it content. Shame is painful in direct proportion to the degree of positive affect it limits. As Tomkins has stated, shame will occur whenever desire outruns fulfillment. To the extent that we humans seek pleasure we must experience shame. Indeed, much of the folk wisdom about the nature of heaven seems to be a description of a realm with a better match between desire and fulfillment than that found in nature.

Once, while I was in college, Robert Frost, then poet-in-residence, quipped “Give us the life that the movies show us / That the party in power is keeping from us.” He paused for a moment, then said more seriously that we were all looking for “A world where ask is get / And knock is open wide.” Embedded in these thoughts of the great poet are some of the concepts to which I refer: Life is full of impediments to positive affect, impediments that cause the acute and the fleeting as well as the chronic and the indwelling experiences of shame that so influence our lives and the development of our personalities. We have yet to open the discussion of how this happens, how this affect gets involved in the specific assemblages by which we know shame; yet intuitively you will grasp the idea that any mechanism capable of causing a painful limitation of what we most enjoy is a mechanism capable of involvement in nearly any aspect of human existence.

But even though shame is an auxiliary to the positive affects, rather than a true innate affect in the sense of the first six we described, it bears all of the properties of the other affects. Shame affect is an analogue of its stimulus. Triggered by an impediment to positive affect is a highly amplified impediment to further positive affect. The specific “feel” of shame is that of an impediment to something we had wanted or enjoyed or which excited or pleased us. Although the affect is triggered initially by chance occurrence, later we learn new triggers for shame. The more information we can absorb, the more functions that can be handled by the ever-evolving brain of our species, the more triggers for shame can be found.

Notice that Tomkins does not claim shame to be an “off-switch” for interest–excitement and enjoyment–joy, a mechanism strictly analogous to the action of dissmell and disgust in turning off hunger for specific substances when hunger is at its height. Shame affect is a unique biological mechanism. It is called into action when the organism remains fascinated by whatever had triggered its interest or remains desirous of communing with whatever or whoever might next have been a source of the contentment, relaxation, or mirth associated with the affect enjoyment–joy.

So the innate affect shame–humiliation is conceptualized as a mechanism that throws the organism into a painful experience of inner tension by attempting to reduce the possibilities for positive affect in situations when compelling reasons for that positive affect remain. As in the example mentioned above, when we hail a woman who turns out to be a stranger, we remain quite interested in that person, quite fascinated by her appearance for the same reasons that made us hail her a moment earlier. Just because she has turned out to be someone other than we expected does not really make her a bit less interesting. Had she indeed turned out to be who we expected, she would have been someone quite accepting of our rapt attention to her face, body, and costume. But she is not that particular friend, and our searching gaze can be interpreted by her as an unwelcome intrusion. It is shame affect that is triggered to reduce our level of interest in a situation where every other stimulus operates to continue the process of amplifying our interest.

The more excited the organism, the more shame is triggered when this impediment is sensed; the more enduring our interest in the stimulus that triggered our attention, the more shame will be needed to reduce our interest. Similarly, the more we had been in the throes of enjoyment–joy, of the contentment produced by some stimulus capable of producing pleasure by reduction in stimulus level, the more shame affect will operate to interfere with the ability of the affect program to continue its action of amplifying the decrease in stimulus density!

A dauntingly difficult concept? You bet. Let’s take an example and see how it works. Consider the plight of a small child who sees an interesting stranger as a novel stimulus and is burning with excitement at the prospect of studying his or her face and body. Had the child no machinery for the recognition, storage, retrieval, and comparison of patterns, it might not know that this individual is a stranger. It is these complicated neocortical mechanisms that allow the child to understand the new person as novel and therefore a source of interest. Precisely because the face of the stranger does not conform to any pattern already present in its storehouse of remembered patterns, it becomes a stimulus for the investigation we call interest.

Faces, however, are more than mere sources of interest. They belong to people, and people differ greatly in how they respond to full, unthrottled, push-the-accelerator-pedal-to-the-floor investigation—which, of course, is the normal way small children undertake an investigation. There are rules for the investigation of faces. What starts out as a competent trigger for innate interest is now remembered to be a face, the face of a person who might object to staring, who might get angry—in general, who might not allow the mutualization of interest so important to friendly human interaction. The very pattern that had just a moment ago been the stimulus for interest now can act as an impediment to the further examination of the novel individual.

Suddenly, perhaps providentially, shame affect (the amplification of impediment) is triggered. Eyes that had only a moment earlier been burning with curiosity now are averted, the bodily posture of fervent interest abruptly afflicted by the slumped neck and shoulders of shame. Swiftly the child with-draws behind the safety of mother’s leg, peeking out from behind mother, darting a glance now and again, still burning with curiosity but now partially restrained by shame. Active, full-fledged interest has not been thwarted completely. It has been reduced, impeded, painfully constrained for a little while. The natural desire of the child to explore what it finds compelling will eventually win, but at the cost of experiencing shame.

The innate affect shame, like all the other affects, does not start out as anything remotely like an emotion. It is a biological system by which the organism controls its affective output so that it will not remain interested or content when it may not be safe to do so, or so that it will not remain in affective resonance with an organism that fails to match patterns stored in memory. Unlike the other innate mechanisms, the existence of which can be traced as far back in evolution as the reptile, it is quite recent. Shame–humiliation could not appear until life forms had developed powerful tools for the perception, storage, retrieval, and comparison of complex images. It protects an organism from its growing avidity for positive affect.

Let’s look at another aspect of this. There are lots of times that an advanced organism is fascinated or delighted and continues to experience that affect as long as the stimulus conditions meet the criteria for fascination or contentment. When the stimulus is no longer novel, interest fades; when there is no more stimulus to reduce, enjoyment fades. These are the conditions for what we call boredom.

But now and again, as mentioned a moment ago, the organism becomes fascinated by, or involved in, or starts sharing laughter with, a quite ordinary source for that affect but hits an impediment to the continuation of that affect. Sometimes what drew our interest remains compelling. Whenever we cannot immediately and voluntarily reduce the intensity of the affect so triggered, some mechanism sends a message to the affect center and an interrupt signal is dispatched. The method of interruption is simple—the face is removed from involvement with the fascinating or enjoyable source. It reduces the possibility that new data about this source will be received through perception and tends to limit, attenuate, or impede further affective resonance. It is the physiological mechanism that underlies all of the experiences we come to know as the shame family of emotions.

I think I know how one part of it works, but I haven’t as yet been able to get funding or time for the laboratory experiments to prove my theory. My hypothesis is that shame affect involves a neurochemical, a substance secreted in the ancient subcortical portion of the brain, a compound that causes sudden widening or dilatation of the blood vessels in the brain. I think this substance, which we would call a vasodilator, sets off the mechanism responsible for the sudden loss of tone in the muscles of the neck, causing the head to droop and the eyes to drop from contact with the shaming other. Sometimes you can see the entire body droop in the moment of shame, as when by defeat an athlete is humiliated in public. Perhaps public situations require more interest and attention, and therefore a larger “dose” of this chemical. We hold ourselves more erect in public and therefore are all the more reduced by shame.

Earlier in evolution, before the development of the “higher centers” of cognition, all that shame affect did was turn off the positive affects. But the more complex the brain became, the more functions came to be influenced by shame. In The Emotions, Jean-Paul Sartre described shame as “an immediate shudder which runs through me from head to foot without any discursive preparation” (261), a disruption so powerful that it felt to him like “an internal hemorrhage.” Darwin saw this “confusion of mind” as a basic element in shame: “Persons in this condition lose their presence of mind, and utter singularly inappropriate remarks. They are often much distressed, stammer, and make awkward movements or strange grimaces” (1872, 332).

I can’t think clearly in the moment of embarrassment, and I don’t know anybody else who can. It seems to me that this “cognitive shock” is the sort of thing that could happen if the higher thinking centers were suddenly to be bathed with a substance that dilated blood vessels.

The “time curves” of the other affects seem to fit Tomkins’s hypothesis that each is an amplifier of its stimulus conditions, with a “shape in time” just like its trigger. But shame is “a short fuse with a slow burn.” It lasts longer than I would expect just on the basis of its resemblance to the detection of an impediment. Perhaps it lasts a bit longer because its function is to limit interest or enjoyment when we don’t really want to give up that preceding affect. Continuing interest would then have to be blocked by continuing shame affect, which would make shame last as long as the interesting situation continued to be novel or enjoyable. Similarly, whatever made us experience contentment by reducing stimulus gradient and density might continue to attract our attention and tempt us to allow it to continue making us feel good, which would also make shame last as long as there was a stimulus for us to enjoy. Nevertheless, the other affects seem to be crisper mechanisms. Shame, even at its most fleeting, feels to me like the ebb and flow of a humoral mechanism, something operating over a longer period of time than the others.

Isn’t the blush merely a matter of dilated blood vessels? No one has ever explained why so many of the affects are associated with changes in the microcirculation of the face. We suspect that there are nerve fibers coursing from the subcortical brain to the facial blood vessels, just as the subcortical brain sends bulbofacial nerves to facilitate the contraction of the facial muscles during affect. (It is nerves from the neocortex, corticofacial fibers, that are responsible for voluntary movement of the facial muscles.) But that would not account for the frequent observation that some people blush all over the head and neck, even down to the entire chest! Here, too, I suspect that we are dealing with a chemical substance that dilates blood vessels and that people vary considerably in the amount they manufacture as well as the regions of the body outside the brain that may be affected. It is possible that the vasodilator substance can be manufactured at more than one location, thus accounting for the tremendous variability in individual sensitivity to blushing.

Maybe I’m wrong to postulate a neurohumoral vasodilator. Affect theory, as originally propounded by Tomkins, would suggest that shame affect works by another, equally simple mechanism. All that is needed is for the affect program to reduce tone in the neck muscles and turn the face away from contact with the now problematic situation. That alone would account for much of what we know about shame—whatever had triggered interest or enjoyment would be removed from view. And that movement itself might call attention to the nature of the just-detected impediment, accounting for the moment of confusion associated with shame. Given the wonderful new equipment available to the researcher, my addition to affect theory is easy to disprove. We need only hook up a willing volunteer to one of the harmless new devices that measure circulation inside the brain (by computer analysis of X-ray data) and see if shame causes a transient increase in cerebral blood flow.

Others among my colleagues have suggested that I set up a laboratory capable of detecting the levels of known vasodilator compounds and check the amounts of these substances in the blood of people before, during, and after a shame experience. I look forward to the opportunity to direct such research.

The existence of a “shame chemical” might make a lot of things easier for us psychiatrists. There are many people who are unusually sensitive to embarrassment, who seem always poised at the edge of shame. It might make their lives easier were we able to find and block a chemical system responsible for their discomfort. Such ideas are quite controversial because there is great debate over the very notion of “tampering with the mind.” But, for shame as well as all the other innate affects, such debates must be postponed until we start looking for the neurochemical systems that make them work.

For each of the eight preceding affects I have described some of the assemblies by which it is experienced as feeling, emotion, or mood, and the biological disorders in which it may figure. I will outline some of the ways shame figures in this sort of scheme, but it will take the remainder of the book to fill out this sketch to its full dimensions. It is not difficult to imagine that such an affect mechanism might find its way into a great many assemblies.

Consider, for a moment, some of the properties of shame affect that must occupy our attention. It is a painful experience. Shame interrupts affective communication and therefore limits intimacy and empathy. Shame interferes with neocortical cognition. In its basic role as an impediment to interest– excitement and enjoyment–joy, it can interfere with everything on earth that we enjoy, from the thrill of scientific discovery to the joy of sex.

I like to start with the ideas of Léon Wurmser, the psychoanalyst whose powerful book The Mask of Shame so affected me when I began the study of what was then called “the ignored emotion.” Using affect theory and infant observation, I try to take physiological affect programs that are equally present in all babies and watch them turn into emotions as the growing child accumulates experience. From the opposite vantage point, that of a psychoanalytic archaeologist who searches for the childhood antecedents to adult experience using the uncovering technique pioneered by Freud, Wurmser called shame a layered emotion.

During the moment of shame, he pointed out, certain thoughts are likely to occur—some near the surface, others accessible only by attention to the world of the unconscious as revealed in dreams and free association. “What one is ashamed for or about,” he says, “clusters around several issues: (1) I am weak, I am failing in competition; (2) I am dirty, messy, the content of my self is looked at with disdain and disgust; (3) I am defective, I have shortcomings in my physical and mental makeup; (4) I have lost control over my body functions and my feelings; (5) I am sexually excited about suffering, degradation, and distress; (6) watching and self-exposing are dangerous activities and may be punished” (27–28). Like most writers on shame, Wurmser agrees that the emotion usually follows a moment of exposure, and that this uncovering reveals aspects of the self of a peculiarly sensitive, intimate, and vulnerable nature.

One of the most prominent groups within the shame family of emotions consists of the feelings we know as guilt. Try as we might, we have been unable to find a physiological mechanism, an innate affect, that would explain guilt in any way other than its relation to shame. Included in the experience of guilt is a moment of discovery or exposure. In some cases the exposure is actual, while in other cases it is fantasized. But since shame follows the exposure of what one would wish hidden, we may be sure that shame is involved in guilt.

Certainly guilt feels different from shame; nevertheless, it appears that guilt involves, at the very least, shame about action. Usually this action is one that has violated some rule or law or that has caused harm to another person. Guilt, however, seems to contain some degree of fear of retaliation on the part of whoever has been wronged by our action, so we might say that it involves a coassembly of the affects shame and fear. Empirically, we know that guilt often involves both the shame that lies latent in hidden action and the fear of retribution. Since fear blanches the face, this might be the reason most people do not blush when guilty, despite how redfaced they get when embarrassed. And the vasoconstriction of fear might alter the ability of facial affect receptors to sense the presence of shame.

Such a definition of guilt fits our experience as adults. The most powerful among us feel the most free to undertake courses of action that violate all sorts of rules. Fear of retribution seems unimportant to those who can afford unlimited legal representation or against whom no one has power. Since lawyers can protect us from real damage, with maturity comes relative disdain for civil retribution. Shame is by far the more commanding affective experience in the life of mature, successful people. It is the fall from grace, the loss of face, the forfeiture of social position accompanying exposure, that we fear most.

Throughout the book I will demonstrate that the shame mechanism is triggered often in situations that we do not recognize as embarrassing, painful circumstances when our attention is drawn from whatever had attracted us and we are momentarily ill at ease. The psychologist Helen Block Lewis called this “bypassed shame,” when people experience what she called a “wince” or a “jolt to the self” (1971, 1981), and then begin to worry that the other person is thinking bad thoughts about them. There are many such situations in which we fail to recognize that we are in a moment of shame, so it is important to acknowledge that the affect is not always interpreted as one of the feelings normally associated with shame. In general, what we call “hurt feelings” is caused by shame affect—these are always moments when a positive affect is interrupted by the painful affect of shame.

For the most part, however, shame is known to us in a variety of feeling-states. Even though each of these states carries a different label, each resembles the other in that the core affect is shame. Thus some people might say that they are shy around strangers, embarrassed when they experience shame in the presence of others, and humiliated when this shame is the result of an aggressive attack on them by a valued other.

Later in the book I will show how shame gets to be associated with privacy and the world of the hidden, but for the moment let us look at some of the results of that association. We have noted that shame often attends the exposure of something that we would have preferred kept hidden, of a private part of the self. There are a host of exposure experiences in which we feel a variety of minor shame feelings, and a huge number of circumstances when the betrayal of a confidence leaves us feeling exposed and humiliated. I think that whether we call such experiences shame, embarrassment, humiliation, mortification, discouragement, or by other terms depends mostly on our lifetime experiences of shame affect.

So from my point of view, whenever we realize that our face has turned abruptly from the previously interesting or enjoyable or empathic other, and/or our eyes become downcast, and/or our confusion bad enough that we are unable to talk, we are experiencing some variety of shame. Each member of the shame family of emotions involves, like all the emotions, no more than one or another group of associations to shame—the coassembly of one’s memory of previous similar experiences of shame affect with the shame of the moment.

Everybody who writes about shame has his or her own idea of what these names mean, and I don’t think one list is any more valid than another. Sure, I would agree that the Latin root mort means death, and that the state of mortification implies being shamed to death, but I have no idea what you mean (or what any other individual means) when you differentiate between embarrassment and mortification unless we get to know each other very well and learn about each other’s lives. Implicit in the process of getting to know another person is the sharing of whatever information is necessary to enable us to understand each other’s emotions.

When memory brings forth an earlier but unresolved experience of shame, like the crushing sense of betrayal and loss that once accompanied the sundering of an important personal relationship, the aftershock of such a recollection may leave us in a shame-filled mood for a long period of time. Shame moods may become so toxic that they are interpreted by us and by others as “depression” and push us to ask for psychotherapy.

Nowhere has this been stated better than in this oft-quoted passage by Tomkins:

If distress is the affect of suffering, shame is the affect of indignity, of transgression and of alienation. Though terror speaks to life and death and distress makes of the world a vale of tears, yet shame strikes deepest into the heart of man. While terror and distress hurt, they are wounds inflicted from outside which penetrate the smooth surface of the ego; but shame is felt as an inner torment, a sickness of the soul. It does not matter whether the humiliated one has been shamed by derisive laughter or whether he mocks himself. In either event he feels himself naked, defeated, alienated, lacking in dignity or worth. (1963, 118)

Small wonder that the overwhelming majority of people who seek the aid of professional therapists bring complaints in the realm of shame. Of greater wonder is that until recently we failed to understand the many forms in which the pain of shame is disguised.

Can shame occur when there is no shamer, when no one has attempted to attack our integrity, when nothing has happened to expose us to ourselves? I think so. There are biological disorders of shame just as there are biological disorders of every other affect.

People who take medication to reduce high blood pressure, especially those drugs that decrease our sensitivity to the neurotransmitter norepinephrine, are likely to complain of “depression.” Questioned closely, these patients seem to have a disorder of guilt, telling us that they have done something bad for which they should be punished even when they “know” they have not. Early in the era of experimentation that led to the development of the antihypertensive drugs, patients were given a chemical called alphamethylparatyrosine—a compound that resembles the amino acid tyrosine, one normally found in the body and which is important in the manufacture of norepinephrine. Although the patients given this compound were described only as “depressed,” monkeys given the same medication were seen as socially withdrawn, unable to make facial contact with each other, likely to sit with bowed head and averted gaze. It is commonly said that these chemicals are interfering with the circuitry for normal mood, but I think they do this by producing an internal experience that can only be interpreted by the organism in terms of the innate affect shame.

As I have commented in the case of the other affects whose mechanism of action can be simulated by biological disorders, it seems likely that we interpret certain organic malfunctions in the language of shame. Patients with depression can be divided into two groups on the basis of whether their expressed symptoms are more shame-loaded or guilt-loaded. Those who complain more of guilt seem to respond better to the tricyclic antidepressants such as imipramine. These people are said to have a “typical” depression because psychiatrists have been trained to look for guilt.

Patients whose depression is characterized by complaints about their self-esteem or self-worth, about their need for the approval of others, their sensitivity to rejection, their sense of themselves as failures, or who say that they are in some way defective or deformed, are said to have an “atypical” form of depression or a “social phobia.”† Likely this is atypical only because psychiatrists have not yet been trained to recognize the stigmata of shame, the most prominent affect in each of the symptoms described. Nonetheless, in general these patients respond well to the group of medications called the monoamine-oxidase inhibitor antidepressants, what we call the “MAOI” drugs, and the relatively new family of antidepressants represented by fluoxetine (Prozac). Not long ago one of my patients stopped her MAOI medication more rapidly than I would have liked, and experienced great discomfort. “I’m so embarrassed,” she said over and over. “I feel so ashamed of myself.” She was astonished to see these feelings of shame disappear when she resumed her medication.

Shame is rarely mentioned in psychopharmacologic studies of depression. It would, however, seem logical to implicate shame in a patient complaining of a morbid fear of being deformed. Michael A. Jenike (1984) reports the case of a young woman who had sought psychotherapy for feelings of shyness, low self-esteem, and inadequacy. Two days before her therapist left for vacation, this patient developed the terrifying feeling that she looked like a “monster.” Translating this ideoaffective complex into the language of the body, she claimed that her face had become swollen to monstrous proportions, despite the inability of competent observers to see anything unusual. Tricyclic antidepressants made her feel less depressed but more “crazy,” while she achieved complete resolution of all symptoms within four days of taking her first MAOI drug.

Still other patients describe what I understand as shame due to interference with normal affect physiology—occurring not as a steady-state phenomenon, but all at once, in paralyzing bursts of incapacitating embarrassment or mental pain interspersed with periods of relative comfort. I view this latter syndrome as a disorder of shame affect directly analogous to panic disorder, in which the patient is afflicted by bursts of fear–terror. “Shame panic” usually responds well to varying doses of MAOI drugs or fluoxetine, either medication prescribed in combination with alprazolam (Xanax). Experience with this clinical condition leads me to suggest that in it, neither type of medication works adequately without the other.

I mentioned earlier my impression that guilt is a combination of shame and fear, the two affects fused and hooked together with a wide range of memories of situations in which we were caught doing forbidden things or breaking rules. It seems logical to me that there is one form of depression caused by biological interference with the circuitry for shame, and another form of depression that occurs when the circuitry for fear is affected as well. There are other affects gone wrong in depression, notably distress (which accounts for the tearful quality of depression); the term depression itself has become little more than a wastebasket for a large group of uncomfortable and persistent moods.

Some people are afflicted with chronic, unremitting shame. This noxious affective state can be produced by interference with the normal functioning of hardware or software; yet in either case the individual is equally uncomfortable. On occasion I have studied adults whose character structure was based on an apparent “decision” to hide shame through the false (and highly exaggerated) display of both interest–excitement and enjoyment–joy. Everything, everybody interests them; anybody, any situation can provide an opportunity for the mutualization of laughter. Woe to the unwary other who fails to accept such a brittle and artificial demand for mutualization, for such refusal of attunement is greeted by suspicion and anger quite resembling a paranoid display.

Tomkins (1963) and Kaufman (1989) have described another device used to disguise chronic shame: Unable to prevent the lowered lids and averted face of the innate affect itself, these individuals force themselves into direct gaze by tipping the head back, jutting the chin forward, and adopting a disdainful look through which they seem to be observing us as a lower form of life. Several well-known television interviewers/personalities utilize this system of defense against shame.

There is much more to say about all of these aspects of shame, but for the moment I wish only to remind you that the innate affect is a physiological mechanism, a firmware script that guarantees the operation of functions that take place at a number of sites of action. The script for shame is dependent on the integrity of certain structures in the central nervous system, on many chemical mediators that transmit messages, and on the organizing principle stored in the subcortical brain as the affect program. No matter what shame or any other affect “means” to us, it is essential for us to keep in mind that we are dealing first and foremost with a mechanism that is initially free of meaning.

“Shame,” says Tomkins, “strikes deepest into the heart of man.” Sota, in the Talmud, says that “humiliation is worse than physical pain.” Elsewhere in the Talmud, Baba Metzia says that “shaming another in public is like shedding blood.” The poet Vern Rutsala speaks of “the shame of being yourself, of being ashamed of where you live and what your father’s paycheck lets you eat and wear. . . . This is the shame of dirty underwear, the shame of pretending your father works in an office as God intended all men to do. This is the shame of asking friends to let you off in front of the one nice house in the neighborhood and waiting in the shadows until they drive away before walking to the gloom of your house.”

We have much to do if we are to explain how a physiological mechanism, one that evolved as a modulator of other physiological mechanisms, has evolved further into so potent a source of pain. Shame is intimately tied to our identity, to our very concept of ourselves as human. To the extent that man is a social animal, shame is a shaper of modern life. It may be that shame has built the border between what each of us knows as the outside world and the inner realm we have come to call the unconscious. Some have gone so far as to say that there would be no unconscious were it not for shame! It is to the ubiquity of shame that we will now turn our attention.

*Tomkins (1963), 123. This example is used by Izard (1977, 395), to whom it is often attributed incorrectly.

†Liebowitz et al., 1985