THE COMPASS OF SHAME

So here we are. We have learned a lot about the nature of affect itself and concentrated on the operation of shame affect. We have a new theory for the nature of sexuality that explains why there is such a bond of union between sex and shame. All of the drives, including the sexual drive programs of the generative system, and all of the affects cause recurrent experiences that form the nidus of the self. We can see how affect and sex are linked to the birth of the self.

What we have discussed amounts to a survey of the major situations in which an individual will experience shame affect throughout life. These experiences become the library through which, as an adult, each of us will browse when attempting to think about any current situation in which shame affect has been triggered. We have shown how shame and pride are tied to matters of size, shape, dexterity, skill, dependence and independence, love, and sex, as well as the very idea of an individual self. It is affect that makes things matter, and shame affect that makes these particular things matter in the manner described.

Each of the drives creates a need which, when satisfied, brings pleasure, just as the mitigation of any negative affect becomes a positive experience. But there is more to pleasure than the satisfaction of drives or the release from discomfort. Every activity we find both pleasant and urgent has been made so or assisted by the positive affects of interest–excitement and enjoyment–joy. These particular affects lie at the heart of sociality and conviviality. They animate and enliven most of what we enjoy in life. Notwithstanding their immense power as motivators, both of the positive affects are capable of being interrupted by a host of stimuli that can act as impediments.

At all times it is important to remember that shame affect is triggered any time interest or enjoyment is impeded, and that relatively few of these many such situations are known to us as members of the shame family of named emotions. Reconsider the example of the young woman whose husband interrupted their sex play to ask that she yield to his demand for the ritual of candlelight and music as an accompaniment to intercourse. We have every reason to believe that the painful “hurt feelings” she experienced (on returning to their bed from the requested tasks to find him reading a magazine) were caused by shame affect. To her, this was an episode of “hurt,” which became the emotional experience of “rejection” only after she had “thought about it for a few moments.”

A generation ago, working without the concept of innate affect, Helen Block Lewis referred to such incidents as examples of “bypassed shame,” characterized by a “wince” or a “jolt” to the system. Like most of the previous investigators of shame, Lewis felt that there was a proper way to express or experience shame; the many variants she described were seen as defenses against “true shame.” She described “bypassed shame” as if the triggering incident had evaded some brain center in the path toward recognition; to her it was a form of shame in which we do not acknowledge the emotion because awareness would lead to bad feelings about the self. Nevertheless, she points out that “bypassed shame” is usually accompanied by the thought that another person holds us in disrepute.

Today, in the language for shame I have introduced, this would be considered just another script for shame affect. Rather than being bypassed, the affect has shown up in an assembly of trigger and response that does not appear in our library of experiences already labeled by the shame family of words. Nevertheless, what we experience as the “wince” or “jolt” she describes is the characteristic cognitive shock associated with the physiological phase of shame. In each case, it is easy to demonstrate that it had been preceded by an impediment to positive affect; the thoughts that follow it are typical of the cognitive phase of shame emotion.

To complicate matters, as we go through life we learn to attach shame to situations that might not have triggered it innately. (Only if society attaches importance to fashion will style be linked to shame.) The number of situations in which the innate affect shame–humiliation can be triggered is immense and constantly growing.

Yet it is improbable that every time any affect is triggered we are required to scroll through all our memories of similar situations and bring them into current awareness. It appears most likely that similar situations are grouped and stored as a bundle, and that a current experience of affect is compared to the bundles themselves. The existence of such bundles, which Tomkins calls scripts, allows us to bypass the full review that would be required by their absence. Such a script involves both a compression and a condensation of all previous episodes, summated as an experiential pattern. The death of a friend does not trigger a review of every shared experience. What we call mourning is actually a review of the scripts, the bundles of affect-laden experiences that involve us with that now-departed other.

Whenever we are aware of our affective reactions (in other words, should we happen to have a feeling), we are capable of forming an emotion by recalling previous instances of that affect. Thus, each time shame affect is triggered, we are drawn backwards in time to experience some representation of our lifetime of similar or related shames, whether or not we recognize the incident as typical of shame.

Providentially, the phenomenology of recall does far more than this, for such a use of memory might have led to the evolution of mechanisms for forgetting far more powerful than those now in place! Stored along with our reminiscences of shames past are our recollections of all the ways we have made ourselves feel better when hurt. To have lived until this moment, each of us has accumulated a library of defenses against painful experiences. The stacks of our library are loaded with entire scenes in which we, or others we have observed, have handled the noxious experience of shame affect in a tremendous variety of styles. Intimately associated with the affect is our history of reaction to it.

Until this point I have used the definition of emotion introduced by Basch in 1976—an assemblage consisting of an affect and our associations to previous experience of that affect. From the work presented so far, it seems clear that we must alter this definition to take into account both the trigger to affect and our reaction to it. Every emotion actually consists of a four-part experience initiated by some stimulus, which then triggers an affect, after which we recall previous experiences of this affect, and then, finally, react to the stimulus in some manner influenced by that affective history.

There are, then, four explicitly different phases of the shame experience. Each of the innumerable forms of shame is ushered in by some clearly discernible triggering event. Usually this will be some easily defined impediment to whatever positive affect had just then been in progress. Yet to be discussed are other, learned triggers to shame, some of which can be set off even when we are already in the throes of a negative affect—shame can take us from bad to worse. But always there is a trigger, some event that ushers in the unpleasant flow of events we call shame.

Second in this sequence, of course, is the innately scripted action of the affect itself, a series of physiological events occurring at sites of action all over the body. During this phase, whatever positive affect we had been experiencing is impeded painfully by a programmed mechanism that pulls our eyes away from whatever had been the object of our attention, dilates blood vessels in the face to make us blush, causes our neck and shoulders to slump, and brings about a momentary lapse in our ability to think.

Yet this cognitive shock, this transient inability to think, lasts but a moment before it is replaced by a flood of new thoughts as, quickly, we become aware that we have been “hit” by an affect. As if in swift compensation for its brief failure, our cognitive apparatus now makes access to its script library to find and organize all information relevant to shame affect; one attempts to see what script this new experience fits, or whether a script must be changed. Such is the cognitive phase of shame, the period during which feeling begins to blend into emotion. By and large, it is the history of our prior experiences of shame and the importance to us of these painful moments that will determine the duration and intensity of our embarrassment.

Notice that I did not suggest that the cognitive phase of the shame experience involves review of the individual memories, the discrete occurrences of shame which have until now occupied our attention. What we review in this brief period is the group of shame-related scripts. Each script is the equivalent of a computer chip—a miniaturized integrated circuit from which all relevant prior shame experiences can be retrieved, reconstituted, revived into full affective power. And each of these collections of memories has been grouped in such a way that the collection itself achieves further urgency by assembly with affect in the manner we defined earlier as affective magnification. It is the script (rather than the individual memories) that contains the real power.

There is a fourth and final phase of the shame experience, composed of our repertoire of responses to the felt quality of these scripts. Among the great variety of responses we note those that fall loosely into two major groups—patterns of acceptance or defense. Were we humans more creatures of assent than justification and preservation, I doubt there would be much need for books such as this. It is our avoidance of the lessons to be learned from shame that causes us the most trouble. Occasionally, however, we do examine the impediment and learn from it. Recognizing both the affect and our historical experience of it, we may decide to use this particular moment of shame as the spur to personal change—an unexpected opportunity to make ourselves different.

Say, for a moment, that I have fancied myself a trim and youngish individual, the dashing and debonair creature of my post-adolescent dreams. Now somebody produces a poolside photograph that reveals me as a paunchy, graying, middle-aged physician. I react, of course, with a degree of embarrassment directly proportional to the “importance” to me of my prior misconception of self. But what if I study the offending image, turn to my wife, and announce, “Look at this. You were right. I have gained a lot of weight. Time to diet.” Exposure has triggered shame but led me to work in order that I might approach more closely my idealized self-image. A year later I will smile tolerantly at the memory of that photograph and credit it as the stimulus that made me work toward a healthier, more modish figure.

All of us know that such a reaction is rare indeed. I am much more likely to respond defensively, to do something that mitigates the pain of shame but requires no alteration in my being. The moment of shame, this combination of physiological and cognitive factors to which we have devoted so much attention, always leads us to a psychological crossroads. Which way we turn, how we handle this moment, what we do next, turns out to be a major factor in the architecture of our character structure, our entire personality.

The reactive phase of shame involves all the habits, defenses, tricks, strategies, tactics, excuses, protections, buffers, apologies, justifications, arguments, and rejoinders that we have devised, witnessed, or stored over the highly personal series of events we know as our lifetime. So swiftly do we shift from affect to response that often the triggering stimulus is linked in our awareness neither with the intervening feeling of shame itself nor with the complex assortment of thoughts that follow it, but with the angry or tearful or humorous style of reaction that comes to define us as individuals.

Often these reactions are situational, linked directly to some feature of the triggering event. Take, for instance, the example of a man who has been involved in an extramarital liaison. Denounced in church by his religious leader, our miscreant is likely to bow his head in deference. Yet the same allegation, made by his wife in the privacy of their home, might lead to angry denial; made by barroom cronies, a host of amusing stories; and if by an enemy, a physical altercation. In each case, exposure has triggered shame affect that in its turn has called forth some series of remembered scenes. These four scenarios differ both in the style of reaction—the reactive phase of the shame experience—and the social milieu of the otherwise similar triggering event.

Remembered at all by our philandering protagonist, each of these would be recalled not in terms of shame, but as four completely different experiences. I do not mean to suggest that these experiences are devoid of reference to shame, but that certain mental mechanisms operate to shift his attention away from shame toward something else. For the experience in church he might use the term “disgrace”; by his wife he has been “unfairly” accused. He might think of the interaction with his friends as an opportunity to make a couple of good jokes; certainly he would see his reaction to an “insult” as reasonable and proper.

All of his life experiences of disgrace will be grouped to form a script—sequences linked by specific affects. These sequences of actions and affects must, of course, differ somewhat each time they are set in motion, but the important feature is that they tend to recur with regularity. Similarly might he form scripts that group his experiences of the avoidance of shame through denial or disavowal, or his use of self-deprecating humor to minimize the toxicity of shame, or the use of anger to turn the tables on whomever has caused him shame.

Tomkins’s use of the term derives from our experience of scripts in the theater, where an author sets down rules for the behavior of others. Psychological scripts are formed when we assemble a set of related scenes for the purpose of generating responses that will thereafter control and direct the outcome of such scenes. Scripts are how we realize that life events are apt to fall into predictable sequences and that our responses to both the events and the sequences tend to be predictable. Since many of these scripts contain rules for the handling of powerful affective experiences, we develop affective responses to the scripts themselves. So complex and pervasive are the habits and skills of script formation that we adults come to live more within these personal scripts for the modulation and detoxification of affect than in a world of innate affect. So it is that we adults “understand” or experience our emotions differently and find the very concept of innate affect so difficult to grasp.

If you share my fascination with the long history of theories about the nature of emotion, then this is the point at which you will exclaim “Aha!!” Now we know why nearly all of the competing theories have been at least partially correct. The definition of a mature emotion that I am promoting here takes into account the display noted by Darwin and the visceral changes so important to James and Lange, as well as the perceptions essential to their theory. In the chapters that follow you will see ample justification for DeRivera’s observation that mature emotion causes us to move toward or away from self, toward or away from other. Ideas and memories stored within the unconscious can also magnify affect-related scripts—Sartre, Freud, Jung, Hillman, and many other theorists are also partially right. And the neurobiologists are also correct when they demonstrate the existence of so many circuits that produce subroutines important in normal and abnormal emotion, and that can be triggered by aberrations in the chemistry and structure or the brain. Linking all is the concept that mature emotion depends on hardware, firmware, and software.

You will remember that each affect is both an analogue and an amplifier of its stimulus conditions—that is why we keep referring to shame affect as a painful analogic amplification of any impediment to positive affect. If the function of a defensive script is to reduce the toxicity of a particular affect, the very fact that the script reduces a negative affect makes it (as a whole) a positive experience and a source of positive affect. Alternatively, imagine that we group as a script some assortment of sequences that we find repulsive. Our sense of disgust at the entire sequence, at the script itself, will tend to color everything within that script with disgust affect. It is this coloration to which Tomkins refers as affective magnification. Scripts take on their own affective climate, which, in turn, magnifies all of the affect contained within the scenes themselves.

When an event occurs, we analyze it to see if it fits into a script; we try to interpret it as one of a series of events that has been analyzed before. We are capable of having an affective response to an imagined outcome or to a set of possible outcomes. It is to this set of possibilities that we now generate affect; since this new affect will influence everything within the set, we call the mode of influence magnification rather than amplification to distinguish between the higher and the lower orders of influence.

Affective magnification is affect multiplied by affect. If the affect contained within the scripts is the same as our affective reaction to those scripts, then the process of magnification produces something like “affect squared.” In the process of magnification, affect amplifies something that is already being amplified, conferring on it a new and far more intense quality of experience. It occurs when many scenes are grouped together into a script on the basis of their similarity, and when these scripts take on a life of their own because they have been made “more so” by affective magnification. You will recall that Demos explained innate affect as a mechanism that converted quantitative information into a qualitative experience. Now we add the idea that affective magnification causes both a quantitative and a qualitative increase in the intensity of that experience.

When something occurs that fits into a script, it is experienced with a degree and intensity of affect far exceeding what one might have expected on the basis of its action as a trigger to ordinary innate affect. This is akin to what I suggested as the rationale for the formation of normal mood—each remembered scene is capable of acting as a stimulus to further affect, accounting for the duration of mood. Mood, therefore, can result from a script that controls the time span of triggered affect more than its intensity. And, of course, there are loads of scripts in which affect rises in intensity, as when we become increasingly angry at something the more we think about it.

For many of us, almost any affect feels better than shame. If we are to convert the experience of shame into something less punishing, we must develop some group of defensive scripts that foster such a transition. All that is interesting or calming in life can be impeded; each experience of impediment will trigger shame. Great vigilance is needed to monitor life for the possibility of shame, to prevent it wherever possible, and to limit its toxicity when it cannot be prevented.

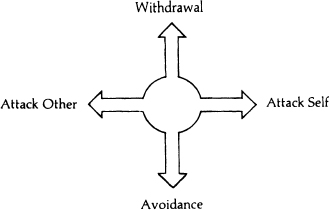

In the case of shame, our defensive scripts fall into four major patterns, which I have organized as the compass of shame. For the adult, depending on just what had triggered interest–excitement or enjoyment–joy and the “who, what, why, when, and where” of the source of the impediment that triggered shame affect, we will choose a defensive strategy that best fits these particular circumstances. In any such given sequence of events we will fly to one of the four points of this compass:

Each of these categories represents an entire system of affect management, a set of strategies by which an individual has learned to handle shame affect. They are characterized by widely divergent assortments of values. In each, shame affect is experienced differently—the purpose of the strategy is to make it feel different. All of us, from time to time, use the techniques and strategies of all four systems. Nevertheless, to the extent that we can be said to have a personal style (a group of attitudes and actions by which we are known to ourselves and others), we tend to favor one or another of these systems of defense. Essential to the birth of the self is the development of the reactive phase of the shame experience.

The four poles of the compass contrast and compare in many respects. Those who withdraw are the most willing to experience all of the physiological manifestations of shame and all of the thoughts that flood us during the cognitive phase. For them, the physiological qualities of the affect provide escape from an intolerable situation. Escape, in the language of withdrawal, is swift and occasionally total.

Raised in different families, in different circumstances, some people find the experience of shame so toxic that they must prevent it at all costs. Flocking to the avoidance pole of the compass, they engage in a number of strategies to reduce, minimize, shake off, or limit shame affect. It is at this locus of our compass that we will find most of those who abuse chemical substances, engage in defensively hedonistic activity, purchase the services of the plastic surgeon, and go out of their way to distract our attention away from what might bring them shame. Indeed, as a patient pointed out to me the other day, those who suffer the most from chronic shame are the most likely to be seen as “narcissistic” because of their constant attention to anything and everything that might produce even more shame.

Withdrawal and avoidance scripts have a peculiar relation to the idea of time—the former is a rapid, the latter a slow and deliberate movement away from an uncomfortable situation. As we will see later, in both script families one can react with different degrees of remoteness. Mild withdrawal and mild avoidance are considered quite normal, while those whose reactions to shame induce the greatest degree of remoteness or self-aggrandizement are considered truly ill.

Those who find intolerable the helplessness and isolation characteristic of shame-induced withdrawal will tend to take over the experience of shame, to place it under their own control within the system of behavior I call attack self. They are willing to experience shame as long as we understand that they have done so voluntarily and with the intention of fostering their relationship with us.

In the remaining quadrant of the compass we find the community of those who experience as most unbearable that part of the cognitive phase of shame which discloses information about their inferiority. “Someone must be made lower than I,” says the denizen of the attack other pole. Every incident of domestic violence, of graffiti, of public vandalism, of schoolyard fighting, of put-down, ridicule, contempt, and intentional public humiliation can be traced to activity around this locus of reaction to shame affect.

Just as the withdrawal and avoidance poles bear some special relation to the signifier of time, the attack self and attack other poles house scripts that focus on an object in space. These latter scripts recast our relationship to others in some way that reduces the toxicity of shame.

The four poles of the compass of shame function as libraries that house some of the most important affect management scripts in our repertoire. At each pole we will find a different assembly of auxiliary affects brought in to shore up its defenses: withdrawal is likely to be accompanied by distress and fear; attack self by self-disgust and self-dissmell; avoidance by excitement, fear, and enjoyment; and attack other by anger. Of all the drives, the one most closely identified with the sense of self is the sexual drive mechanism of the generative system. At the locus of withdrawal we will tend to find sexual abstinence, impotence, and frigidity; attack self will be characterized by sexual masochism; the avoidance pole by sexual machismo; and the attack other pole is likely to be rife with sexual sadism.

Poets, novelists, psychologists, playwrights, and all the other commentators on the human condition have forever been telling us there are vast differences in the ways men and women express and experience shame, some of which were easily explained in the previous chapters when we discussed gender dimorphism. Yet it is in the scripts formed by the reactive phase of shame that we will find the remainder of the reasons for these observations. Finally, each of these defensive systems operates over a wide range, from the most mild, useful, acceptable, and benign to behavioral systems that are clearly pathological.

In the pages that follow I will explain the features of the compass of shame, delineating for each pole all the mechanisms to which I have alluded in the paragraphs above. Viewing the adult experience of shame in this manner, it is easy to develop new ways of mitigating the toxicity of shame. From this schema will emerge a logical approach to the psychotherapy of shame-related problems. Too often, writers on shame confine their attention to behavior and feelings that represent only a small part of the full picture of shame. It is my hope that the very concept of a compass of shame will make clear the full range of shame-related experiences. Let us start with what my colleague Léon Wurmser calls shame simpliciter—shame itself, shame as withdrawal.