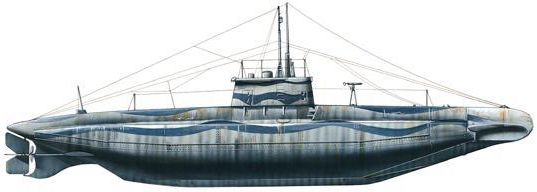

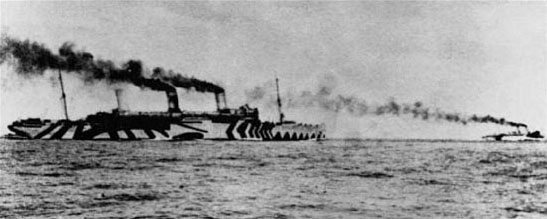

A German U-boat in the Mediterranean. The impact of submarines in World War I was greater than anyone had anticipated beforehand. The U-boat campaign was perhaps Germany's best chance of forcing Britain out of the war.

As war got underway, it became quite clear to the Admiralty that the threat posed by German submarines had been grossly underestimated. The world's most powerful navy was even briefly forced to retreat to distant harbours by the U-boats. Their main impact, however, stemmed from their use against merchant shipping. During several periods of unrestricted warfare, events such as the sinking of the passenger liner Lusitania ensured the notoriety of this potent underwater weapon.

Experiments with submarines began as early as the seventeenth century. Various governments showed interest in the early work of such pioneers as Robert Fulton and J.P. Holland, not least because it seemed to offer the possibility of attacking hostile warships that were engaged in a blockade. This was how the Confederate submarines were used during the American Civil War, which saw the first sinking of an enemy ship by a submarine. Interest in the potential of this new weapon grew rapidly towards the end of the nineteenth century. The internal combustion engine offered a superior source of propulsion compared to hand cranks operated by the crew, while torpedoes provided an effective weapon that could be used from a reasonable distance, as opposed to the spar torpedo, which had sunk as many users as targets. There were still reasons for scepticism, however, due to limited seaworthiness, poor reliability and limited range; yet as these characteristics improved, the submarine had to be taken more seriously.

Although there had been earlier experiments, the first time a submarine sank a ship was on 18 February 1864. The CSS H.L. Hunley sank the sloop USS Housatonic, which was blockading the harbour of Charleston, South Carolina. The Hunley used a spar torpedo (an explosive charge at the end of a long iron pipe), but itself sank with the loss of all hands due to damage sustained in the attack. The danger to the submarine's own crew was a common feature during its early years: before this final operation, no fewer than 35 men had died on the Hunley in accidents, including its builder, H.L. Hunley himself. As with other earlier submarines, the boat could travel short distances underwater, but attacked its targets on the surface, albeit operating partially submerged and presenting a small target that was difficult to see.

The Confederate submarine Hunley, the first submarine to sink an enemy warship.

France showed particular interest in early submarines, which were seen as promising a means of neutralizing Britain's advantage in battleships, preventing naval blockades and allowing a more lethal campaign against merchant shipping. By 1901, France had 31 on order. Interest was also shown in the United States (which by 1902 had ordered seven) and also Greece, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Sweden and Turkey.

Britain was a little slower to see the submarine as a useful weapon, with many in the government and the Royal Navy reluctant to encourage something that seemed to threaten the dominance of the surface warship, in which Britain held such an advantage. It was also seen by some as an immoral, even cowardly weapon: Admiral Sir Arthur Wilson called it ‘underhand, unfair and damned un-English’. Indeed, at the 1899 Hague Conference on the laws of war (where the delegates included such naval luminaries as Mahan and Fisher), Britain suggested banning the submarine and the torpedo, but other states were reluctant, not least because Britain was less keen to see similar restrictions placed on battleships. However, the fact that so many states were acquiring submarines, not least France, meant that building some was prudent, even if only for experiments in how to counter them. Hence, in 1901, Britain ordered five. Some of the submarine's proponents in the Royal Navy recognized its wider potential and within a few years of commissioning the first boats, Britain envisaged using them for defending ports and narrow straits. Others, such as Jacky Fisher, conceived a more ambitious, offensive role than mere coastal defence, realizing that Britain could use them near the enemy's bases or in other areas where he was locally dominant. Many remained sceptical, however, with Admiral Beresford nicknaming them ‘Fisher's toys’.

Germany was, ironically (in view of later events), one of the last great powers to adopt the submarine, which it did by ordering a single one in 1905 and beginning trials in 1907. Thereafter, there was a swift technological advance, with the development of larger, longer-range boats and trials of a diesel engine in 1913, which was safer, more reliable and promised a genuinely ocean-going submarine. This delay was due in large part to the priority placed on the battlefleet by Tirpitz in his naval expansion plans, despite his experience as head of the torpedo arm.

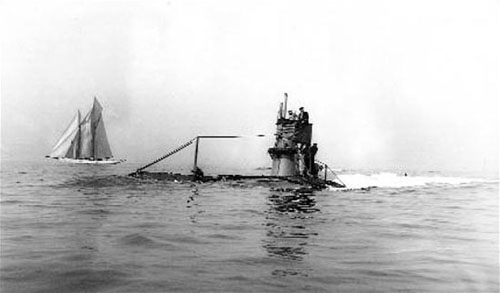

U4, an early German submarine. Germany was a relatively late entrant to the submarine trade, due to the emphasis placed on battleships. At the beginning of the war, she had one of the smallest submarine forces of a major naval power, but these included some of the world's most advanced boats.

A British A-class submarine at sea. The A-class was one of the first to enter service in the Royal Navy, from around 1903. They were small boats, designed only for short-range, coastal operations and served during the war in harbour defence.

The gun on a British E-class submarine. This class represented a considerable advance on the A class, and entered service from 1911 onwards. The boats were capable of overseas operations and were used offensively during the war, including in the Baltic and in the Dardanelles.

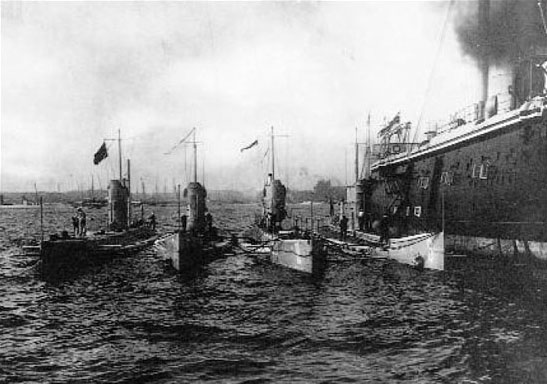

At the beginning of the war in 1914, France had the largest submarine fleet with 77 boats, with Britain in second place with 55, the United States third with 38 and then Russia with 33. Germany had only 28 U-boats (the term being an abbreviation of Unterseeboote). These figures are somewhat misleading, however, since most of the French and British boats were very small and limited in capability, whereas 10 of the German boats were very modern and powered by diesel engines, and Germany had many more under construction.

The great advantage that submarines possessed was their stealth, due mainly to the ability to operate beneath the water for short periods of time, though also because their low profile made them hard to spot when they were operating on the surface at night. This characteristic was useful both for evading patrolling forces and for ambushing surface ships, and allowed a navy to operate even when its opponent was dominant in traditional terms. Their main weaknesses – some of which would reduce as the early technical capabilities of the submarine improved – were that they had limited range and speed, especially when operating underwater, that they were relatively fragile and that they carried only a limited stock of torpedoes – typically six at the beginning of the war.

‘None of the main powers anticipated the use of submarines against merchant shipping. Most doubted that they could be an effective weapon due to international law restrictions’

Generally, the submarine was seen as useful for reconnaissance, and for the defence of coasts and harbours. Alternatively, for the more ambitious, it might be used to pick off enemy warships (especially damaged ones) in support of the battlefleet, which was still universally seen as the centrepiece of naval power. Ideas about using the submarine offensively and at a greater distance grew along with improvements in its capabilities, but the envisaged target was still enemy warships.None of themain powers anticipated the use of submarines against merchant shipping.Most policy makers and analysts doubted that they could be an effective weapon due to the restrictions imposed by international law, failing to appreciate how the pressures of warmight lead to the casting aside of legal conventions. One exception was Jacky Fisher, who warned about the dangers of attacks conducted without warning against merchant ships; however, his prediction was dismissed as unthinkable.

EARLY USE AGAINST WARSHIPS

The initial use of submarines by both sides was, as expected, against warships. Both Britain and Germany established patrols near their own bases and then began to send their boats over greater distances, seeking out the enemy rather than waiting for him to attack. On 6 August 1914, Germany dispatched 10 U-boats to patrol the North Sea. On 8 August, this force made contact with the enemy and U15 conducted the first, albeit unsuccessful, torpedo attack on a British warship, the pre-Dreadnought HMS Monarch. The following day, U15 was spotted on the surface, apparently suffering mechanical problems, and was rammed and sunk by the light cruiser Birmingham. One other U-boat was lost to unknown causes, probably a mine. The results of this first scouting foray by U-boats were a disappointment, inflicting no damage but losing one-fifth of the force. Nevertheless, this five-day patrol proved to German commanders that U-boats could remain at sea for longer periods and could operate over greater distances than had been assumed, which helped to advance more ambitious views as to the possible roles of U-boats.

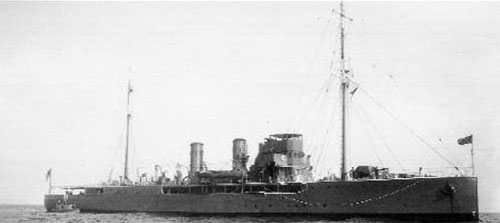

As it became clear that the Royal Navy was not going to behave as anticipated by charging headlong into German-dominated waters, more distant offensive patrols were conducted. U-boats were sent into the Firth of Forth where their first success was achieved on 5 September 1914, as U21 under Lieutenant Otto Hersing sank the light cruiser HMS Pathfinder. A heavier blow followed on 22 September when U9, commanded by Otto Weddigen, sank the three armoured cruisers Aboukir, Cressy and Hogue. On 15 October, the same U-boat attacked and sank the light cruiser HMS Hawke. Later in the month U27 sank a submarine and the converted seaplane carrier Hermes. On New Year's Day 1915, U24 sank the pre-Dreadnought Formidable. This was the greatest achievement so far by a submarine, although no Dreadnought had yet been sunk – indeed, none would be sunk by a submarine during the entire war.

These events made it clear to the Admiralty that the submarine threat had been grossly underestimated. The result was not only changes to operations at sea (with high speeds, zigzag courses and destroyer escorts becoming standard procedure) but also a withdrawal by the Grand Fleet from Scapa Flow for much of the period between September and the end of November 1914, while anti-submarine defences there were improved. The world's mightiest expression of naval power had been compelled to retreat by the threat from the submarine; it is difficult to imagine a more striking example of the impact of a new weapon. The naval arm that was of least interest to Tirpitz caused greater concern to the Royal Navy than the High Seas Fleet (on which he had lavished so much financial and political capital) would throughout the war.

The Baltic saw many clashes at sea between Germany and Russia. The Royal Navy considered various schemes for operations there, including some rather risky amphibious operations. In the end, British involvement was largely confined to submarines, which operated from Russian bases and caused considerable damage and disruption.

While the Royal Navy found its activities severely constrained by the perceived threat from U-boats, the impact of submarines was far from one-sided. Operations by British submarines caused much the same concern and operational inconvenience to the German Navy as the U-boats caused to the Grand Fleet. While the threat posed by submarines had helped compel the Admiralty to drop the close blockade conducted directly off the enemy bases, the submarine also provided an alternative. While small submarines guarded the British coast against attack, larger and longer-range Royal Navy boats scouted waters close to Germany, including the Heligoland Bight and the Skagerrak, which would have been prohibitively dangerous for surface warships. They achieved some successes, notably E9, under Lieutenant Commander Max Horton (who became famous in the Battle of the Atlantic in World War II). On 13 September, this submarine sank the light cruiser Hela – later hitting another cruiser with a torpedo that failed to explode – and on 6 October sank a destroyer.

The crew of HMS Swift, a destroyer flotilla leader, commissioned in 1907. She saw extensive service as part of the Dover Patrol, notably an action in April 1917 when, with HMS Broke, she sank two German destroyers from a large force aiming to attack anti-submarine forces.

Even a navy that was dominant in the conventional terms of the battlefleet could utilize the valuable ability of submarines to operate where the enemy enjoyed a local superiority. In October 1914, Britain sent three submarines into the Baltic, to disrupt German operations there. One was forced to turn back, but two, E1 and E9, succeeded in making the dangerous passage despite mining, heavy German patrols and difficult navigation. The impressive early results achieved by these two boats – damaging a pre-Dreadnought and sinking a destroyer, a collier, a minelayer and a naval transport – resulted in more being deployed in 1915. Four E-class boats braved the straits while four smaller C-class vessels were towed to Archangel and then transported by canal into the Baltic. They operated from Russian bases and achieved a number of successes, not least in helping to disrupt a German amphibious operation against Russia over the summer. E1 torpedoed and damaged the battlecruiser Moltke, E8 sank the armoured cruiser Prinz Albert and E19 sank the light cruiser Undine. Later, they switched to attacking the German shipments of iron ore from Sweden. Germany had much the same difficulty in countering submarines as her opponent and, just as the Royal Navy found, the wider disruptive effect of submarine operations was even greater than the direct losses. Training was adversely affected, in an area that had previously been considered safe, and destroyers were switched away from the High Seas Fleet to patrol against submarines.

HMS Aboukir. The sinking by a single U-boat of the three old armoured cruisers of the ‘live bait squadron’ was a great shock to Britain, and clearly demonstrated the dangers for such ships operating in areas where U-boats were present.

Submariners on both sides found it difficult to attack enemy warships. While a battlefleet was under way at reasonable speed and following a zigzag course, it was a challenging target for the slow U-boat. It was not possible to maintain submarines on patrol for extended periods, yet if they were dispatched only on definite warning that the opposing fleet had left port, they were usually too slow to get into position in time for an attack. Their low speed and the difficulty of communication between them and surface ships, as well as shore bases, also made it difficult to coordinate their activities with those of the rest of the fleet. Nonetheless, it was clear that an important new element had been added to naval power.

U9 photographed in 1914. On 22 September 1914, U9 (commanded by Lieutenant Otto Weddigen) came upon three Cressy-class armoured cruisers and sank all three in quick succession. This was a considerable achievement, not least since the U-boat was only carrying six torpedoes.

U-BOATS AGAINST COMMERCE

The use of submarines against merchant shipping had not been anticipated before the war other than by a few visionaries such as Fisher. This was largely due to the assumption that they would obey international law, which imposed restrictions on submarine operations – impositions that threatened to make it impossible to use them effectively.

Submarines were bound by ‘prize rules’ that had been developed for surface raiders. These held that a merchant ship could be stopped, boarded and searched for contraband (that is, war materials). If found to be carrying contraband, the vessel could then be confiscated or sunk – on the condition that the crew were first placed in a position of safety, which putting them in lifeboats would not fulfil unless it occurred very close to the shore. These rules were straightforward for a cruiser or converted auxiliary raider, which would overpower any merchant ship and had either enough personnel to put a prize crew on board a seized ship or had enough space to take onboard the crew of a ship that was to be sunk.

The rules caused great difficulties for submarines, however, since by surfacing to challenge a merchant ship they made themselves vulnerable to attack by a modest armament that would not trouble a cruiser, or even to ramming. Moreover, they could not spare a prize crew (typically having a complement of about 40 officers and ratings) and were too small to take on any captives. There was therefore a tension between observing international law, which meant imposing severe self-limitations, and allowing the U-boats to attack in their most effective manner. It was perhaps inevitable that as Germany began to feel the strain of the war, her strategy would shift towards the latter course.

Though many ships were lost to mines laid by U-boats, the first direct attack on a merchant ship occurred on 20 October 1914, and was conducted strictly in accordance with international law. The small British steamer Glitra, en route for Norway, was stopped by U17, inspected and scuttled by a boarding party only after the crew were placed in lifeboats, which were then towed to the Norwegian coast (the proximity of which made it acceptable to leave the crew in lifeboats). On 26 October, a different and more ominous attack was carried out, as U24 torpedoed, without warning, and damaged the French steamer Amiral Ganteaumme. The commander believed the people he could see on deck were troops; they were in fact refugees from Belgium, 40 of whom died in the attack.

From November 1914, some commanders in the German Navy began to advocate wider and more systematic attacks on British commerce. As the expected rapid victory on land failed to occur, there was a desire to identify alternative means of pressuring the Allies. Targeting Britain's trade seemed an obvious option, but as Germany's surface raiders were gradually hunted down and there seemed to be no imminent prospect of the German battlefleet defeating its British counterpart (particularly after its narrow escape at the Battle of the Dogger Bank in January 1915), the U-boats seemed to be the ideal alternative. The restrictions being observed fatally limited the effectiveness of the campaign, it was argued, and should therefore be shaken off. Other senior naval officers and, even more, the civilian members of the German Government (particularly the Chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg), opposed any widening of the U-boat campaign that would violate international law. Their principal concern was the risk of alienating neutral powers, perhaps even provoking them to join the war on the side of the Entente. Proponents of submarine warfare replied that observance of the niceties of international law not only jeopardized a potentially war-winning weapon, it also overlooked the fact that such actions could be portrayed as a legitimate response to the British blockade, which itself seemed to be straining accepted international conventions. Why should neutral ships carrying supplies to Britain be left unmolested while those supplying Germany were being intercepted?

Due to the relatively low number of torpedoes carried by individual U-boats, their commanders preferred to use gunfire against their targets, where possible – a risky venture if the intended victim turned out to be a Q-ship.

From the start of the war, Britain imposed an economic blockade on Germany to put pressure on its ability and will to continue waging war. It sought to prevent imports of war materials and even food, which also involved seeking to prevent imports into neutral states being re-exported to Germany. The blockade was enforced by cruiser patrols to check merchant ships and, if contraband were found, send them into British ports. These patrols were backed by intensive diplomatic and intelligence efforts. The blockade caused some friction with neutrals, although – much to the indignation of the German Government – less than the U-boat campaign, since at worst it resulted in the seizing and compulsory purchase of cargoes deemed contraband, rather than the death of merchant seamen and civilian passengers. Much war material still reached Germany through neutral countries, but the gradually tightening blockade began to exert severe pressure on her.

As the course of the war failed to take a turn for the better for Germany, and as the British blockade bit harder, pressure in the media and Parliament grew to unleash the U-boats. More naval officers and then finally the Kaiser himself were won over. On 4 February 1915, Germany proclaimed that all waters around Britain would from 18 February be treated as a war zone, with all British ships being sunk without either any warning or any measures to protect the crews. It warned that neutral ships were also subject to attack, since they could not be distinguished from British ships. Some naval officers felt that this statement was too much of a political compromise, since it failed explicitly to state that all shipping, including neutral vessels, was forbidden in the war zone. In practice, the protection for neutrals was considerably watered down by the instructions given to U-boat captains that the safety of their vessel was their first concern, therefore they should not surface to examine a ship and check whether or not it was neutral.

The United States protested strongly and warned the German Government that it would be held accountable for any American ships attacked. As a result, after some bitter debates, the German Government ‘clarified’ the initial statement, insisting that only enemy vessels, rather than all merchant ships, would be sunk, adding that measures would be taken to ensure the security of neutrals. For Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer, these modifications for diplomatic consumption ‘ruined’ the campaign. The navy was ordered to instruct U-boat commanders not to attack neutral-flagged ships unless it was certain that they were enemies using a false flag; yet the instructions passed on to the captains were surprisingly permissive, giving them as much latitude as possible to attack merchant ships. They were ordered to pursue the campaign ‘with all possible vigour’, but told that they should not attack neutrals – although flags and other markings suggesting neutrality were not to be taken as proof that a ship was truly neutral, and other factors, such as its course, should be taken into account; in addition, commanders would not be held responsible for any mistakes made.

U6, U7, U10 and U12 photographed in 1913. At the start of the war, the Imperial German Navy had no more than 28 U-boats. None of the four boats pictured here would survive the war: one was sunk by a British submarine, one by a mine, one by a British destroyer and one by another U-boat in a case of ‘friendly fire’.

The frequent changes in policy and in instructions to commanders reflected deep divisions within the German Government between its military and civilian members. They were torn between maximizing the impact of the U-boat campaign and minimizing its diplomatic repercussions. Germany was trying to have it both ways, reassuring the United States that American ships would not be deliberately targeted while also explicitly relying on the terror effect of attacks to deter neutrals from trading with Britain. ‘Unrestricted submarine warfare’ was really a misnomer, since some ships had been torpedoed without warning before 18 February, while even during the height of the campaign, restrictions of some sort were often imposed. The restrictions on U-boat operations were rarely either total or entirely absent, but were rather a matter of degree with considerable variation.

‘When the failure to achieve decisive success on land led Germany to start attacking commerce, both sides had to improvise – with Britain's efforts to do so rapidly becoming the key to her remaining in the war’

Germany had not envisaged waging war on commerce and had therefore made no plans for it. Similarly, though, Britain had not anticipated the need to defend merchant shipping against submarine attack. When the failure to achieve decisive success on land led Germany to start attacking commerce, both sides had to improvise – with Britain's efforts to do so rapidly becoming the key to her remaining in the war.

THE FIRST ‘UNRESTRICTED’ U-BOAT CAMPAIGN

The opening of the campaign on 18 February 1915 saw an average of only about five U-boats at sea each day; of the total force in service, some were incapable of long-range operations, others were involved in training crewmen or were under repair. Germany was slow to build more, due to the long-lasting assumption of a short war. Nevertheless, numbers grew, including the smaller UB and UC boats (the latter being minelayers) of the Flanders Flotilla, designed to operate from captured Belgian ports at Zeebrugge and Ostend. The larger boats operating from the bases of the High Seas Fleet in Germany were well placed for the North Sea, but in terms of reaching the Atlantic, they had a less favourable geographical position than their successors in World War II would enjoy with bases in occupied France and Norway.

On 19 February, the Norwegian tanker Belridge was torpedoed and damaged by U16, becoming the first neutral vessel to be attacked without warning. The United States protested furiously, since this was a ship belonging to a neutral state, heading from one neutral country (the United States) to another (the Netherlands). The German Government apologized. A few days later, U8 sank no fewer than five British ships in the English Channel. The campaign was rapidly taking effect and losses mounted.

By the end of 1914, only three merchant ships of 3048 tonnes (3000 tons) in total had been sunk by U-boats (all figures for losses are from Tarrant, V.E. The U-Boat Offensive 1914–1945). In January and February 1915, sinkings rose to seven ships totalling over 17,780 tonnes (17,500 tons) and nine ships of 23,165 tonnes (22,800 tons) respectively. In March, as the unrestricted campaign got fully underway, losses rose to 29 ships of 90,935 tonnes (89,500 tons) before falling back in April to 42,165 tonnes (41,500 tons), due to a reduction in the number of U-boats operating. In May, the tonnage sunk soared to over 108,700 tonnes (107,000 tons) – with another 20,300 tonnes (20,000 tons) sunk in the Black Sea – with the June figure even higher at 117,150 tonnes (115,300 tons). These losses, while serious, were lower than the rate of construction of new merchant ships, while the total tonnage available to the Allies was further increased by pressing into service impounded vessels belonging to the Central Powers. This was a one-off bonus, however, while future new construction would be lower due to the reallocation to military production of shipyards, skilled manpower and raw materials. By May, more than 20 neutral ships had been attacked without warning. That month, however, saw a striking incident that would eventually curtail the first unrestricted campaign.

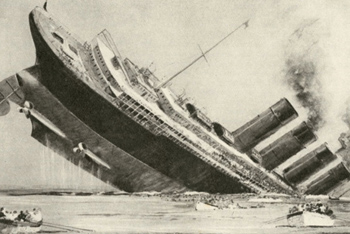

THE SINKING OF THE LUSITANIA

On 7 May 1915, U20 (commanded by Lieutenant-Commander Walter Schwieger) was heading home after sinking three merchant ships during her cruise. She sighted the passenger liner Lusitania, en route from the United States to Britain. The U-boat happened to be steaming a favourable course for an attack on this fast ship, so the captain submerged and, having recognized the distinctive vessel, ordered an attack in full knowledge that his target was a passenger liner. The torpedo struck home and blew an enormous hole in the side of the ship. It was followed by a large secondary explosion, caused (according to different theories) by the ship's steam generation plant, coal gas or the detonation of some of the munitions that the ship was carrying as part of her cargo. Lusitania sank rapidly, her increasing list as she went down hindering the launch of lifeboats and increasing the casualties. Some 1200 passengers were killed, including 128 Americans. The attack caused outrage among neutrals, particularly the United States, but President Woodrow Wilson was deeply reluctant to become involved in the war and confined the reaction of his government to a strong protest. Nevertheless, American public opinion shifted strongly against Germany – and was considerably less critical thereafter of the impact of the British blockade.

The result of an attack on a merchant ship. When Germany began to shrug off the restrictions of international law, the rising losses to U-boats began to have an increasing impact. The first campaign ended before large numbers of U-boats were available, but it was a warning of what was to come.

The threat to merchant ships from U-boats was very difficult to counter, given the surprisingly intense opposition from within the Royal Navy to the tried and tested solution of convoy and escort. Britain had little time in which to learn how to conduct an effective anti-submarine campaign.

There was much concern among the civilians in the German Government about the impact of such actions, though naval commanders insisted that the policy should continue. Although sinkings, including attacks without warning, continued over the summer, the German Government tightened restrictions somewhat, assuring the United States Government that there would be no more attacks on neutral ships or on passenger vessels of any nationality. The Chief of the Naval Staff, Admiral Bachman, objected that such demanding conditions were unworkable, and insisted for his crews that there be a clear choice between unrestricted warfare and ending the campaign entirely. He was replaced. His concerns that the modified policy would prove impossible to implement in practice were confirmed on 19 August, when the British passenger liner Arabic, en route for the United States, was sunk by U21, killing 44 people, including three Americans. There was renewed public fury in the United States at this violation of the pledge that no passenger ships would be sunk (a guarantee that was easier to offer than to put into practice). Another sinking of a passenger liner followed on 6 September when U20 torpedoed the Hesperian, killing 32.

Once again, the issue was debated within the German Government. Some in the navy, notably Tirpitz, pressed for attacks without warning to continue while the civilian officials, especially Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, urged a return to full observation of prize rules. This time, the Kaiser supported the latter viewpoint. On 18 September, U-boats were ordered to cease patrolling the Western Approaches and the Channel, and to act in accord with international law in the North Sea. The first ‘unrestricted’ U-boat campaign had ended.

The campaign had inflicted painful losses, but not on a scale that threatened Britain's participation in the war. The later part of the campaign had seen merchant ships sunk at a higher rate than new ones were being built, with over 165,615 tonnes (163,000 tons) plus another 15,240 tonnes (15,000 tons) in the Mediterranean and Black Sea sunk in August 1915. There was relief in the Admiralty that the campaign had ended and perhaps also complacency, though the latter sentiment was based on a misunderstanding: the British anti-submarine measures had, despite huge effort, been largely ineffective in meeting the technical and conceptual challenges posed by this new weapon.

Walter Schwieger was the commanding officer of U20, which on 7 May 1915 torpedoed and sank the liner Lusitania, killing about 1200 civilians. The outcry in the United States over this action compelled the German Government once again to tighten the restrictions on the U-boat campaign. Schwieger was killed in 1917 when his U-boat struck a mine.

The Cunard passenger liner Lusitania was more than a ship, she was a symbol. When she was launched in 1906, she was the largest passenger ship in the world, and had been designed explicitly to take back the Blue Riband for the fastest crossing of the Atlantic from German competitors. This she duly achieved, both westbound and eastbound. She was part of a programme by which the British Government provided a subsidy for ships that could be converted to armed merchant cruisers in wartime. As it happened, however, the Admiralty decided that she would not be useful in such a role and she continued as a passenger liner. Other liners had been sunk before the Lusitania, but her fame and the large number of people killed (especially Americans) made the reaction more furious.

COUNTERMEASURES

The Allies were fortunate that the U-boat campaign began on a relatively small scale, giving them precious time in which to devise counters. This advantage, however, was outweighed by the difficulty of creating effective means of anti-submarine warfare. The use of U-boats against merchant shipping was an entirely unprecedented and unforeseen type of threat. Experiments had been conducted before the war, but had not been a particularly high priority and had not produced any useful countermeasures.

The most obvious problem was the lack of any means of detecting and attacking submerged submarines. When operating on the surface, U-boats could be spotted – during the day, at least – and were vulnerable to attack by gunfire or even ramming. It was their ability to submerge quickly at the first sign of danger that made them so challenging. The common image of anti-submarine warfare as depicted in war films shows destroyers using sonar and depth charges to dispatch their prey, but these innovations took some time to emerge: an effective depth charge was not in service until 1916 and Asdic (the original, British name for what the United States called sonar) was invented at the end of the war, though never used operationally. Both of these problems, detection and attack, received a great deal of attention but a solution took time – and meanwhile, losses were mounting.

For detecting submarines, attention initially focused on hydrophones, underwater microphones that could pick up the sound of a U-boat's engines. These were first used in 1916 and represented a step forward but were subject to important limitations: they initially could not give any indication as to the direction of a detected submarine and they required the ship using them to be stationary (very dangerous if submarines were present), to prevent the noise of its own engines or of water passing its hull from drowning out the sound of any nearby U-boat. Another attempt to reveal the location of submerged submarines was the use of indicator nets, which were equipped with flares or contact mines that would alert patrolling forces if a U-boat became entangled in them.

As for attacking U-boats, the obvious solution was to destroy them in their harbours. The bases in Germany were too well protected to be attacked, so attention focused on those of the Flanders Flotilla in occupied Belgium. During 1915, they were subject to repeated attack by bombing raids and, later in the year, bombardment by purpose-built monitor gunboats. These efforts had little effect, due to the difficulty of achieving the accuracy required and to the heavy protection of the targets.

Some countermeasures to the U-boat threat were highly imaginative. This ship is protected by ‘dazzle camouflage’. Introduced late in the war, it was designed to make it more difficult for a U-boat commander to judge the course of his intended target and thus harder for him to attack.

The U-boats would therefore have to be destroyed at sea. Early use was made of ‘explosive sweeps’ or ‘explosive paravanes’, which were charges towed underwater that could be detonated if they struck a submerged U-boat. A better solution lay in depth charges, which were dropped behind a patrol ship to explode at a predetermined depth. The idea had been conceived before the war and the first request for them was made shortly before its outbreak, but it took some time to design one and there was then a further delay before it could be made available in the numbers needed.

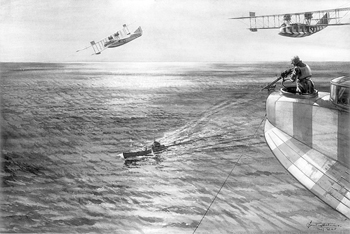

The threat from U-boats was met in part by the increasingly widespread use of an even newer technology: aircraft. They included slow, non-rigid airships (or ‘blimps’), aeroplanes operating from land bases, seaplanes (which took off from and alighted on the water, using floats attached where a land-based aeroplane would have wheels) and, later, flying boats (which, unlike seaplanes, floated on their main fuselage). Aircraft were able to search large areas of the sea to spot U-boats. They were less effective at attacking any U-boat that was spotted, however, since it was a difficult target for bombs, and air-dropped depth charges did not appear until the next world war. Aircraft could call up warships to attack a U-boat or could simply force it to submerge, reducing its range and effectiveness. The technical characteristics of aircraft improved rapidly during World War I, and hinted at the far greater role they would play in the 1939–45 anti-submarine campaign.

H12 Curtis ‘Large America’ flying boats attacking a submarine. Aircraft would eventually prove to be a vital element in meeting the threat from U-boats.

An alternative approach was to entice the U-boats to launch an attack themselves, luring them to the surface and to approach within range of a trap. Attempts to do this were assisted by the fact that it was appealing for a U-boat commander to surface and to sink a merchant ship with gunfire, or by placing explosives on board, rather than to use up his limited supply of torpedoes. One version of the U-boat trap used in summer 1915 was to have a trawler towing a submarine; when a U-boat challenged the trawler it would alert the submarine, which could sink the attacker. This practice resulted in the sinking of two U-boats, but others survived to report back and provide warning of this technique.

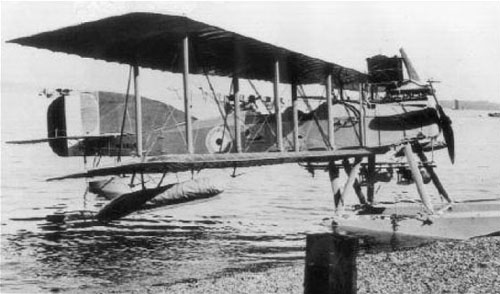

The Short ‘improved’ Type 184 Seaplane. This was one of the most widely used naval aircraft of the war, with over 900 being built from 1915. It was used for reconnaissance and as a bomber, and also holds the distinction of being the first aircraft to sink a ship with an air-launched torpedo (during the Dardanelles campaign).

The second form of the trap built on the longstanding practice of arming merchant ships to give them some capability for self-defence against raiders. A U-boat, highly vulnerable to gunfire, would not approach a ship on the surface that was evidently armed, so the Admiralty devised the Q-ship, a merchant ship with concealed guns, also first used in summer 1915. Believing the Q-ship to be a juicy target, the U-boat would surface and approach, often encouraged by some of the crew faking panic and abandoning ship, at which point the Q-ship would uncover its guns, run up the White Ensign (showing itself to be a warship) and engage the would-be attacker. During the war, Q-ships sank 11 U-boats, which some have seen as a modest return given the large number that went to sea (as many as 180 in 1917). On the other hand, the possibility of vessels being Q-ships forced U-boats to attack from underwater, where their speed was lower than on the surface, using up their torpedoes and thus reducing the number of attacks made on each patrol.

Yet another way to solve the detection and attack problem was to try to prevent the U-boat from reaching the shipping lanes by using mines and barriers. Britain placed considerable faith in minefields, laid off German bases or in narrow waters through which U-boats had to pass to reach their patrol areas. These had less success than hoped: the mines could be swept up by the German Navy, and, in particular, the early mines used by Britain were ineffective, often failing to detonate on making contact with a U-boat or tending to explode when no U-boat was near.

The English Channel was a critical stretch of water for the campaign, partly because of the amount of local traffic between Britain and France, partly because ships on longer journeys were concentrated there, and also because it was the quickest route for U-boats to reach the Western Approaches. Britain therefore devoted considerable resources to creating a barrier across the Channel, using nets, mines and booms, backed by patrolling warships and airships. This was difficult to achieve due to the strong tides and the weather, and U-boats could simply dive beneath the minefields. The result was not the expected impassable barrier but merely a nuisance, albeit one that caused sufficient inconvenience for the German Navy to order U-boats to avoid this route, and to take the longer alternative around the north of Scotland, between April 1915 and the end of 1916.

A British convoy leaves port with non-rigid (‘blimp’) airships. Airships were widely used in support of convoys during World War I. Their great advantage was the ability to remain on station for long periods, although their utility was reduced by their low speed and lack of manoeuvrability.

There was one way to protect valuable ships that had a long history of success: convoy. This involved gathering ships into groups that were guarded by escorting warships, rather than allowing them to sail independently. Some advocated convoy as a means of safeguarding essential merchant ships against attacks by U-boats, yet this response was rejected by the Royal Navy in the early years of the war. Some naval officers felt that modern conditions meant that convoy would no longer work, while others believed that it was merely defensive and trusted offensive patrols to seek out, hunt down and destroy the U-boats. Each time convoy was suggested, a range of arguments was raised against it, while losses rose. At first, they were below the level that would seriously threaten Britain's ability to keep fighting, because of the limited numbers of operational U-boats and the restrictions imposed from time to time on their activities. Yet eventually, the unity of convoy and escort would have to be reconsidered.

The Arabis-class sloop HMS Lupin, part of the larger Flower class, launched in May 1916. The U-boat threat presented an urgent need for small, relatively cheap escort vessels that could be built in the large numbers required. Several dozen Flower-class vessels were built as minesweepers and as convoy escorts.

A further problem for the Admiralty was the limited number of ships suitable for anti-submarine operations. There were many destroyers, but they were largely occupied with duties supporting the Grand Fleet. In any case, they had been designed for use against torpedo boats and other surface ships and lacked a capability against submarines. Nor did they exist in the number required. Britain therefore embarked on a rapid construction programme of smaller anti-submarine vessels, such as the 1220-tonne (1200-ton) Flower-class sloop. As an interim measure, some 500 trawlers were taken up and armed with guns to form the Auxiliary Patrol. Submarines proved useful in taking on other submarines, sinking some 18 U-boats by the end of the war, but still found it difficult to locate their prey.

Increasing use was made of aircraft, which had two great advantages: their height gave them a view superior to that of any ship, while their speed allowed them to cover a wide area. Britain made considerable use of various types of aircraft, which had different strengths and weaknesses against U-boats. Airships enjoyed a long endurance and an ability to carry heavy loads, including wireless equipment, but were slow and difficult to manoeuvre, making them all but incapable of attacking U-boats. Seaplanes were faster and more manoeuvrable, but gradually gave way to flying boats, which were faster, larger, capable of operating in rougher seas and had more crew members – and hence more eyes watching for U-boats; however, they were vulnerable to attack by enemy aircraft. One major limitation was reach, as much of the U-boat campaign took place in the Western Approaches, which were beyond the range of British aircraft. This range was further pushed out by creating new air bases in Cornwall and south Wales, as well as establishing bases for seaplanes and flying boats in the Isles of Scilly, but it remained limited.

Each of these issues – locating U-boats, attacking them, preventing their passage to patrol areas and the inadequate number of anti-submarine vessels – was challenging, and together they caused great difficulties. These problems were greatly magnified by a fundamental flaw in the way that the limited number of anti-submarine forces were used. Rather than adopt the familiar technique of ‘convoy and escort’, by which the Royal Navy had protected merchant ships for centuries, the Admiralty and the great majority of naval officers rejected its use against U-boats, deriding it as ‘defensive’, and clung to supposedly ‘offensive’ patrolling.

Some of the arguments against convoy were respectable, notably the concern that it would mean doing the U-boats’ job for them by gathering their targets together, allowing them to attack many ships at once. Besides, the advent of steam power gave merchant ships far greater choice of routes, so it was suggested that they were safer traveling independently. It was also argued that by delaying ships until a convoy could be formed, slowing merchant ships to the speed of the slowest and limiting the number of voyages that could be made, a system of convoy entailed reducing the efficiency of the Allies’ scarce shipping tonnage. Merchant crews would not be capable of keeping station, it was felt, especially at night or if the first language of captain and crew was not English. Moreover, having many ships arriving at once followed by long gaps without any arrivals was far from the most efficient use of port facilities. It was also objected that the total number of ships arriving at and departing from Britain's ports was simply too great to be put into convoys.

One of the problems facing the British anti-submarine forces in the early years of the campaign was the lack of any means of attacking a submerged submarine. Depth charges provided the answer to this problem, especially once they became available in larger numbers.

A German mine-laying submarine. As well as attacking merchant ships and warships directly, U-boats caused significant losses by laying mines off ports or in key stretches of water. This forced the Allies – who conducted their own mine-laying campaigns – to devote enormous resources to sweeping the mines.

Furthermore, convoys would be of little use without escorts, and early on in the war the number of destroyers available was hopelessly inadequate – and there was tough competition for them from the Grand Fleet, which also needed escorts.

It is not quite true that the Admiralty was totally against convoy, as it embraced the system for military transports such as troop ships. Convoy was firmly rejected for merchant vessels, however. The bias for offensive patrolling neglected the principal advantage of the U-boat, which was its stealth in the vast areas in which it could be operating. Offensive patrolling was not, in fact, the active, positive solution that it was portrayed to be. Charging around the seas looking for submarines was in fact remarkably ineffective, particularly when such an obvious alternative existed. The reluctance of the Royal Navy to embrace convoy seems, in retrospect, rather baffling and it came close to costing Britain the war.

THE SECOND U-BOAT CAMPAIGN

The second U-boat campaign began in September 1915 with the reimposition of prize rules following the Lusitania and Arabic incidents, and went on until 1 February 1917. During this period, the U-boats acted under varying degrees of restrictions. At first, this policy resulted in the German Navy deciding to withdraw most of its U-boats from the North Sea, the Channel and the Atlantic, with a correspondingly low level of sinkings in these areas: between October 1915 and January 1916, the monthly average loss there was just over 17,270 tonnes (17,000 tons).

The efforts of the U-boats were redirected to the Mediterranean, where during the same period the monthly total averaged about 82,800 tonnes (81,500 tons) sunk. The Mediterranean, with the Dardanelles operation underway, offered plenty of targets – few of them from neutral states. There was much British shipping passing through, to or from the Suez Canal, as well as the large amount of traffic to and from France and also Italy, which joined the Entente and entered the war against Austria in May 1915. Germany therefore deployed U-boats in the Mediterranean, some from the High Seas Fleet travelling by sea, while smaller boats were sent in pieces by land to Pola on the Adriatic and were assembled there. The U-boats were helped by the fact that the Allies pursued the same flawed anti-submarine strategy in the Mediterranean that they did elsewhere, relying on offensive patrols while merchant ships were sunk in large numbers. Generally, prize rules were observed in the Mediterranean, although it did not escape the notice of Germany that exceptions were not met with the same American protests that such actions in the Atlantic attracted. Losses became so high that the Allies stopped using the Suez Canal, accepting the far longer duration of rerouted voyages around the Cape of Good Hope.

The German submarine U11 in rough seas. The prevailing weather in the North Sea and North Atlantic often meant that the U-boats – not the most seaworthy vessels at the best of times – often had to cope with challenging conditions.

In February 1916, there was another change of policy. The previous month Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff, the Chief of the Naval Staff, had submitted a paper pointing out that the 1915 campaign had damaged Britain, causing shortages in some key raw materials and food, and that a new campaign could draw on a larger force of U-boats and would achieve even more. A restricted campaign, he argued, would cause greater damage than before, but there was no guarantee that it would force Britain to make peace. An unrestricted campaign, on the other hand, would offer the ‘definite prospect’ of forcing Britain to make peace in six months at the most. Further intra-governmental disputes followed. The German Navy pushed once again for the resumption of unrestricted attacks on merchant shipping, which was opposed by civilian members of the government due to wariness about provoking the United States. This bitter dispute resulted in a confused and frequently changing policy. On 1 February 1916, Admiral Scheer (now commander-in-chief of the High Seas Fleet) was told by the Chief of the Naval Staff that a new unrestricted campaign would begin from 1 March. On 23 February, however, he was informed that the Kaiser had been persuaded by the civilians in the government to reverse this decision.

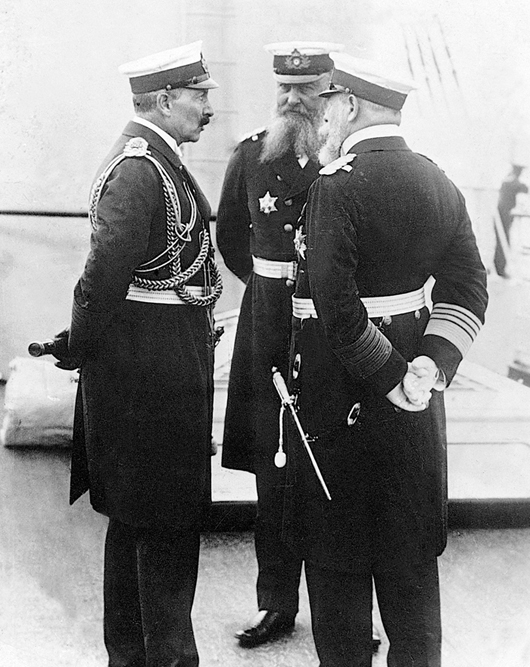

The Kaiser, Tirpitz and Holtzendorff in discussion. The extent to which Germany was to obey the conventions of international law – if at all – in the prosecution of the U-boat campaign was the cause of bitter and prolonged disputes within and between the naval leadership and the German Government.

The result of the renewed debate was that from the beginning of March 1916, U-boats were permitted to attack all enemy vessels without warning within the declared war zone around the British Isles and the Western Approaches. Armed merchant vessels could be attacked even outside this area, although only if positively identified as armed, which required a risky close approach for confirmation. No passenger liners were to be attacked without warning. The German Navy chafed over the remaining restrictions – indeed, Tirpitz resigned over the issue – and a number of passenger liners were still sunk, either deliberately or in error due to the confusing orders.

In early March, the balance of opinion shifted once more and the decision was taken to resume the unrestricted campaign from 1 April. Yet again, however, events intervened to complicate policy. On 24 March 1916, UB29 attacked without warning what her commander believed to be a troop transport. It turned out to be the French-owned ferry Sussex. The vessel managed to reach harbour, but the torpedo explosion killed 50 of the 300 passengers on board, including several Americans. Germany initially denied that the attack had been conducted by a U-boat, but when the truth was revealed, there was outrage in the American press and the United States Government sent an official protest, threatening to cut off diplomatic relations unless such attacks ceased. This embarrassing incident strengthened the hand of the civilian opponents of unrestricted warfare, and on 24 April, the U-boats were ordered fully to observe prize rules once again, including giving warning and ensuring the safety of crews. A furious Admiral Scheer decided that this instruction meant that the U-boats could have no practical effect and would suffer many losses due to the increased risk, so he recalled them from the Atlantic and North Sea. This decision seems to have been a bluff, an exercise of brinkmanship seeking to challenge the government and force it to reverse policy again in the face of pressure from Parliament and public opinion. Indeed, even the Naval Staff, believing Scheer to be ignorant of the wider diplomatic factors involved, sought to persuade him to resume operations under prize law, describing his position as ‘either everything or nothing’. He refused. The Chancellor held his ground and the decision stood.

Between April and September 1916, therefore, U-boat attacks on merchant ships were in effect confined to the Mediterranean, where losses remained high. Once again, this was a stroke of luck for the British, because while their anti-submarine measures were still woefully inadequate, the number of U-boats was steadily rising, with 36 operational boats in the High Seas Fleet and the Flanders Flotilla by March 1916. In his memoirs, Scheer argued that an unrestricted campaign should have begun at the start of 1916 – when there were enough U-boats to be effective and any delay would only strengthen Britain's defences – or at least immediately after the Battle of Jutland. He commented: ‘That we failed to do so fatally affected the outcome of the war.’

For the commanders of the German Navy, the temporary cessation of submarine operations against commerce around the British Isles offered one shred of comfort in that it freed the U-boats for use against the Grand Fleet. Admiral Scheer was now able to include them once again in his plans to reduce the Royal Navy's continuing advantage in capital ships. In May 1916, he planned to use a raid on Sunderland to lure the Grand Fleet into minefields and a U-boat trap. From 17 to 23 May, groups of U-boats took up ambush positions off the main British ports. Other boats laid minefields – one of which, west of the Orkneys, on 5 June sank the armoured cruiser HMS Hampshire, killing Lord Kitchener (Secretary of State for War), who was en route to Russia. The plan fizzled out as the sortie of the High Seas Fleet was delayed until 30 May; only one U-boat managed to identify a target and fire torpedoes, which missed. It was therefore an intact Grand Fleet that would fight the Battle of Jutland. The indecisive outcome of this battle would persuade Germany to resort once more to unrestricted submarine warfare in a last, desperate attempt to identify a weapon that could win the war. absent, but were rather a matter of degree with considerable variation.

Part of the funeral procession following the coffin of Lord Kitchener. The Secretary of State for War was perhaps the single highest profile victim of the U-boats. He was killed in the June 1916 sinking of the armoured cruiser HMS Hampshire, en route for Russia from Scapa Flow, when she hit a mine laid by U75.