Chapter 1: Jo’burg to Hotazel

Looking back on it all, I wonder why we didn’t pack the lounge curtains, the kitchen sink and the two cats.

We certainly stuffed everything else into our grey Isuzu diesel bakkie for our two-month Dry Lands journey: four kinds of sardines, mussels, whisky, pickled fish, candles, five torches, six kinds of beans, three dozen two-minute noodle-packs, bags of sucky sweets, wine and sauces of all descriptions. Two laptops, three cameras, six lenses, a big box full of double adaptors, USB leads, batteries, chargers, dusters, a wind-up radio and 100 compact discs. Oh, and a pack of playing cards, for the various gin rummy championships along the way.

I had just been reading about the eighteenth-century journeys of flamboyant Francois le Vaillant, an adventurous Frenchman who never travelled anywhere without his baboon Kees, hordes of camp followers, wagonloads of exotic condiments, trading tobacco, a fully stocked mobile kitchen, 4 kg of chocolate, thousands of beads, hundreds of scarves, an armoury of 15 muskets, a monster of a scimitar and an ostrich feather in his hat.

Maybe some Le Vaillant spirit had rubbed off on me. But this was 2004, a year by which, it may be said, a substantial amount of travellers’ comforts had been established in southern Africa, unlike the late 1780s. These days there are all manner of filling stations, snack shops, department stores, restaurants and yes, even camera stockists, along the way into the wilderness. And we weren’t even going into such a wilderness, just a couple of months of long tar and gravel travel with plenty of human settlements in between. But it’s fun to pretend, so we packed for the expedition as if our very lives depended on it.

We left Jo’burg in the early spring. When we go on long trips, Jules and I always escape from the city after dawn on a Sunday. There’s no traffic except for the breakfast-run Harleys with their trademark engine growls and shiny merchandising, the lycra-clad bicycle crowd with their praying mantis alien-bug helmets and the all-night party studs racing from red light to red light, their shades barely covering little piggy-eyes.

Heading west, we made a detour through the village of Magaliesberg to Koster, from where we would drop south towards Lichtenburg. For a few minutes, we tracked a hot air balloon full of tourists, Brie and champagne as it sailed silently towards the mountains. Approaching Koster, I had a sudden attack of heartburn, brought on by a 20-year-old memory.

The newspaper where I once worked sent a photographer named Noel Watson and me to cover a mampoer (moonshine liquor, sometimes also affectionately called stook) festival in these parts. For good luck we took along some beers and a Welsh Afrikaner called Llewellyn Kriel. We arrived in the early afternoon full of good cheer. We left under cover of darkness, having thrown our names away somewhere in a mealie field. Along the line, there had been a Minister of Agriculture, a bottle of Mafeking Relief and the wink of a farmer’s wife, all of which led to a hasty retreat to Jo’burg, with anxious glances backward.

The previous time Noel and I discovered the dubious pleasures of mampoer was on a farm outside Lichtenburg, at the end of a very long and emotional string of assignments in the vast north-west. Our last port of call was the home of a family who owned a 300-year-old distilling licence. A quick interview, a photograph and we’re outta here, was our plan.

“Sit,” the farmer’s wife instructed us, pointing to a couple of overstuffed chairs on her porch. She brought us a pint of clear, sluggish liquid and two litres of Coke. She warned us before leaving:

“Make sure you add the Coke.”

Well. Fancy an old boere tannie telling us how to drink. Noel and I shared a smirk and set about our business with the mampoer bottle. It was like having lots of little jet-fuel shooters. Then we had an argument about a girl we both fancied, made friends over some more mampoer and decided to fly home in our office car. Our hostess had vanished.

We made it as far as the farm entrance. The gatepost leapt out in front of us like a vicious kudu bull and broke itself on the front bumper. I left a R20 note in a tatty envelope under a stone at the battered gate, with a note saying sorry. Maybe we really should have mixed a little Coke into our jet-fuel shooters.

Jules and I cut through the Verwoerdian facebrick suburbs of Lichtenburg and the only signs of life were the vendors waving the Afrikaans Sunday newspaper Rapport in our faces. The headline read “Ai, Dis Lekker” (Oh, It’s Good). We had just beaten the New Zealand All Blacks in a game of rugby and the platteland seemed to glow briefly – with pride. Lichtenburg, however, looked like a hollow-cheeked, fever-eyed kind of place to live. Out here, it probably pays to be tough and thund’rous of brow. To know your way around a mealie and the innards of an old Mercedes-Benz.

But these were just drive-through observations. For all we really knew, the local Jews, Afrikaners, Englishmen, Indians and Tswana folk were gentle, peaceful and contented citizens.

One thing is for certain. Lichtenburg’s most exciting day ever was 13 March 1926. On that day, a young farmer called Kobus Voorendyk and his labourer Jan (I could not track his surname) were digging fence-pole holes, when Jan upped and yelled:

“Baas, hier’s a diamant!” (Master, here’s a diamond.)

Kobus took the object, which could well have been a shard of broken glass from a bottle left over from a hasty picnic during the Anglo-Boer War, rode off and showed it to the science teacher at the local school. They dropped it in an acid bath and left it for a couple of days. When they returned, it was intact.

That discovery sparked off a world-class diamond rush. By the end of the year, more than 100 000 men were scrabbling in the dirt around Lichtenburg. Such excitement! Kobus Voorendyk coined it Big Time. You had to pay him 15% of anything found on his farm – and you bought his water. Within months, Kobus’s farm was organised chaos. Church ministers and circus performers vied for the hearts and minds of the diggers, you couldn’t see for all the dust and in less than ten years more than seven million carats of diamonds had been excavated from the area. And then Lichtenburg slumped back into a coma. As far as we could see, it still awaited the kiss of a sweet prince – or perhaps a sharp-eyed tourism tout – to bring it back to life.

We slid onto the N14 south and entered the town of Sannieshof.

I’d been here six months before with my friend, photographer Les Bush. We saw a shop in Sannieshof that displayed an Osama bin Laden T-shirt on a rack outside. Which was rather strange, considering we were nowhere near his allegedly favourite spot, the north-west territories of Pakistan.

Les had come to teach me the time-honoured art of birdwatching. He had chosen Barber’s Pan, because it’s an all-year water source and the migrating birds love it here. Little-known fact: birds are South Africa’s most exotic foreign tourists. They fly down from Europe, Russia and Asia, dodging Spanish hunters and Chinese trappers on the way. En route we had seen the Russian-bred lesser kestrels chasing bugs in the mealie lands, perching on telephone lines and enjoying the prospect of a gathering storm, which was turning clouds into castles in the sky.

Once ensconced with beer and binoculars in a hide at Barber’s Pan, I heard Les luring the birds out with enticing calls like:

“Show yourself, or I’ll heave half a brick at you.” Les found a European nightjar dozing on the branch of a dead tree and behaved like an instant Lotto winner as he recorded a “lifetime twitch”, dancing a merry jig in the moonlight.

Never mind. In the face of persistent organic pollutants, expanding agriculture, devastation of habitat, hordes of humans, hunting, acid rain, damming, oil spills, pesticides, fire, electrocutions, the household cat, squatter encroachment, avian diseases, commercial fishing, the caged-bird trade, climate change, deforestation, drought and invasive aliens, it’s great to know there’s a place like Barber’s Pan, where they can rest, congregate and eat in peace.

It’s also a bit of a love nest for the likes of the Diederik cuckoo. The male of the species finds hairy caterpillars, calls the female over and lures her into having sex with him for the price of dinner. Very Old School, the Diederik cuckoo.

I also met the bar-tailed godwit at Barber’s Pan. This major international traveller is a stocky, stilt-like character who can fly up to 8 000 km without rest.

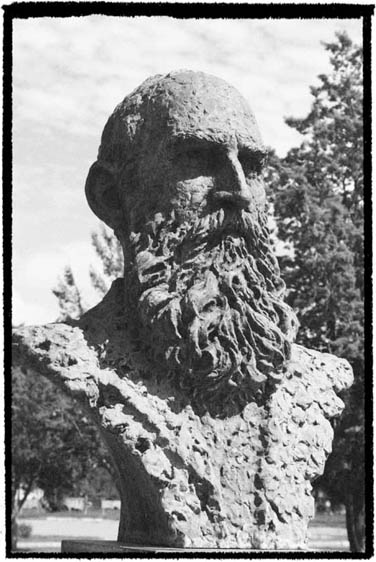

Now, six months later, we drove on, Jules and I, passing Barber’s Pan and entering the town of Delareyville, named after one of the giants of the west, General Koos de la Rey. With some keen foresight he was given the second Christian name of Hercules. De la Rey was considered to be one of the top Boer generals of the Anglo-Boer War, and he was practically invincible in this, his own back yard.

Although not officially schooled in military ways, General de la Rey was a natural soldier, especially in the new type of guerrilla warfare, in which a small, mobile force could successfully pit itself against a larger one. He also had his very own fortune-teller in the form of Nicolaas van Rensburg, aka Siener van Rensburg.

Van Rensburg, about whom much has been written, is an icon for the more apocalyptically focused Afrikaners of South Africa. And as we drove through the west, Jules and I often encountered, stuck mainly onto traffic signs, decals that read: www.siener.co.za. The Boer Nostradamus had a website dedicated to him.

Two of his major predictions were, according to historians, the Boer victory at Tweebosch and the death of General de la Rey, which still keeps conspiracy theorists up at night. Younger South Africans associate a red bull with a buzzy party drink, but the red bulls of Siener van Rensburg’s dreams were all symbolic of the British colonial presence. Every time he dreamt of a red bull injured, limping or dead, his followers would cheer.

The “Sienerism” that interested me the most, however, had more to do with the local diamond fields than the battlefields. Van Rensburg once dreamt about a diamond the size of a sheep’s head. When his son, after futile efforts, quit the diggings in disgust, he sent him back there. Soon afterwards, Van Rensburg Jnr came across a 42-carat diamond. Which isn’t exactly like finding one the size of a sheep’s head, but it means he didn’t leave the diggings empty-handed, either.

My favourite “digger quote” came from a guy called Franz Marx:

“Seeing a diamond in the pan is like spotting a gentleman in a tuxedo standing in a roomful of bums. You can’t mistake him.”

My favourite “digger story”:

Three brothers – built small and compact, like gnomes – once lived and dug for diamonds out near Makwassie. One day, they found a donderse groot goen (an extremely large stone of immense value) just when they’d practically given up on their diggings. Such was the shock of discovery that one brother immediately fell to the ground and had an epileptic fit. The other ran straight into the bush and was never heard from again. The third one, however, had a little more sense. He went into town, bought a bottle of brandy and celebrated until the wheels fell off.

And never you mind about mampoer, either. In the nearby diamond-digging district of Wolmaransstad, Oom Pieter Ernst makes a brandy that will bring tears to your eyes. I used to be a whisky guy, but three strong hits of Oom Pieter’s Klipspruit brandy (run over ice cubes, with a hint of spring water added) immediately converted me to the browner stuff. Although he had to pack for a holiday at the coast, I kept him there ruthlessly, pouring me drink after drink, on the pretext of wanting to hear all his brandy secrets. Smooth brandy from the harsh west – “out of the strong, something sweet” (Judges 14:7).

The western Transvaal, I assured my wife, had always been a place of reprobates. I told her about one Scotty Smith, whose life story reads like a dishevelled pile of facts garnished with fiction. They should erect a statue to this guy somewhere out here, just like they did with the Aussie Outback outlaw Ned Kelly. In fact, Scotty could bring one of these towns some much-needed tourist-fortune. Everyone loves a story, especially one told about a big strong gunman with a twinkle in his eye and couple of coppers for the poor.

Scotty, whose real name was George St Leger Gordon Lennox, came out here with the British army, deserted and made the southern fringes of the Kalahari his stamping ground. He stole horses, robbed stagecoaches, ran illegal firearms and generally behaved like an overgrown child with attention deficit disorder. He was finally caught and sentenced to four years’ jail for armed robbery. He served less than a year, and much of that time was not behind bars, unless you count the hotel bars of Griqualand West. He simply gave his jailers his word of honour and they told him to be back after closing time.

Finally, we arrived at Kuruman. The sky was watercolour-blue, the land sepia and the road a viscous black and white. Jules wanted to see the mission station where the Moffats had worked. She was quite taken with the fact that the explorer David Livingstone proposed to Mary Moffat in this town back in 1845. It was also here that Robert Moffat had the Bible translated and printed in Tswana.

With Yusuf Islam (formerly Cat Stevens) singing Miles from Nowhere on the bakkie tape, we finally drove into Hotazel. Ever since I began this insane road-trekking more than 30 years ago, I had wanted to come to the Kalahari town with the strange name. A manganese mining town, Hotazel had a deadly Sunday afternoon dorpie feel to it. Even the yard dogs were silent. A sign put up by the local Combined School invited us to a performance – later that week – of Ipi Tombi, the “smash hit musical”.

“Welcome to a long time ago,” I said to Jules …