Chapter 13: Namib Naukluft – Kuiseb Canyon

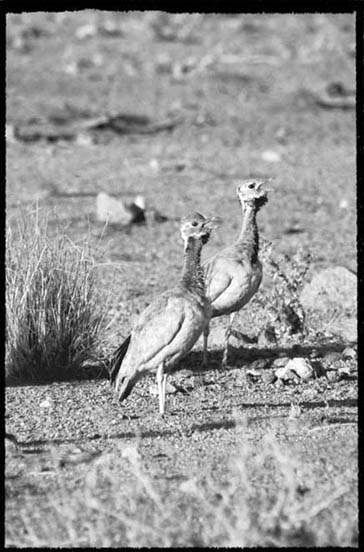

Three large birds flew overhead and landed not ten metres away.

“Rüppell’s korhaan,” whispered Jules, excitedly. “Try taking a photograph – you don’t see them every day.”

“Forget it,” I whispered back. “The minute I lift this camera, they’ll be off. You know about me and birds.”

We slowly advanced on the avian trio. I had my camera at half-port, wondering what evil deeds I had done in this life to make these blighters come down and taunt me so. I’m not famous, in any language, for taking great bird photographs. I’m far too impatient, under-lensed, ignorant of bird habits, lazy, not innovative enough, over-fond of whisky or something. In fact, until this 2004 Dry Lands journey to Namibia, no one would have mistaken me for a photographic St Francis. And yet there I was, preparing to have my heart broken once more by a wild bird flapping away into the distant mountains.

The korhaans advanced on us with purpose.

“All right,” I sighed, “Here goes.” And began burning up some digital camera space. They simply ignored me and waddled past to a little waterhole in front of our accommodation at the Namib Naukluft Lodge. Drank their fill and came walking back up to us again, with an expectant glint in their beady eyes.

Then they began to sing to us for their supper, in a rather throaty, nightclub fashion. Their sound was a 60-Lucky Strikes, late-night blues thing, but still pleasing to the ear. I filled the memory card with, well, memories of these rare Rüppell’s korhaans that were suddenly giving me great credibility as a bird paparazzo. As long as I never revealed the following, rather humbling, facts:

“Ah, that would be August, Sophie and their daughter, Petronella,” the lodge’s staff later told us. “They are habituated. If you keep very still, they’ll take bread from your hand. And if you don’t have any bread, they’ll shout.”

So it was on the wave of a faintly embarrassed bird-buzz that Jules and I wandered into the lodge boma for supper that night. A pleasant evening beckoned: clear skies above, warmish weather and the bonhomie of a German amateur photography school at the next long table. We walked into a steaming, roasting, frying, sizzling blitz of meat.

Within minutes, someone wearing a ridiculously tall, white chef’s hat had heaped our dinner plates with goat chops, boerewors, pork spare ribs and kudu steaks, leaving space for only one slice of cucumber. Jules and I grabbed a beer each and set to. Forgotten were the weeks of breakfast bars, two-minute noodles, beetroot in a box and the other spartan self-catering delights we’d indulged in. Here in medium-to-well Meatland we fell on the cutlets and sausages like timber wolves. And paid the price later, with protein dreams that turned into nightmares with a cast of thousands, as though directed by Bladerunner Ridley Scott himself.

At dawn, I said to Jules that perhaps we needed a very long walk to shake off the meat hangover.

“Mm. Maybe a long sleep first,” she mumbled, and disappeared under the duvet for another hour or so. I went off for some quality time with August, Sophie and their daughter, Petronella. Having just had a drink down at their waterhole, they thought that maybe I could rustle up some bread in the kitchen for them, even if it meant waking a chef up at this early hour. I demurred and asked if I could take some more photographs of them. They told me to piss off. And then I, too, woke up properly.

We had our long walk, Jules, me and about 50 kg of prime, barely digested Namibian braai meat. One of the lodge staff, Deon van der Berg, drove in front of us in his vehicle to a little track off the C19 highway and showed us the two-hour trail. Then he left us to our own peregrinations.

I knew there must be dassies about, culture-starved little hyraxes in need of a verse or two of Neil Young’s Helpless. So I obliged, yodelling across the canyon at unseen rock rabbits, singing and burping for accompaniment, while Jules looked on, suddenly bemused (perhaps shocked, although she still won’t admit it) at her choice of marriage partner. It was only when I broke into a bit of Jackson Browne (from the Running on Empty album, a true classic) that she begged me, on behalf of herself and everything that breathed in the canyon, to please stop. All right, then.

It was a wonderful, wonderful walk. Down the hard, stony canyon past Kanniedood (cannot die) trees (Commiphora saxicola). And rocks whitened by centuries of viscous dassie wee, granite-domed hills, sparrow weaver nests, zebra hoof tracks on the narrow paths, old animal bones in dry river beds and magnificent views over the petrified red dunes to the east.

Millions of years ago, these dunes held their shapes long enough to turn into red sandstone, and they were still frozen in the shapes of breaking waves, or so it seemed from a distance and with a dollop of imagination. Every now and then we came across the smell of cheap perfume, but it was only the flowering of the Ngquni bush.

We returned at mid-morning and the lodge manager, Chris Baas (his surname is the Afrikaans word for “boss” and he sometimes has trouble getting officials to believe this is his real family name), welcomed us back.

“And didn’t you just love the absolute silence of that canyon?” he enquired.

“Yes, yes,” I mumbled, remembering the Neil Young concert I’d given the dassies that morning. It was a kind of touristy, meat-hangover, Hawaiian-shirt thing to do, I admit. I have never again broken out in song to dassies, invisible or not.

We missed lunch and slept instead. Later that afternoon, Jules and I joined Chris for coffee and kuchen (cake) at the outdoor braai area near the korhaan hole. He was making a warthog potjie stew.

“The secret is never to use warthog fat,” he said, stirring the contents of a huge black pot. “It’s as rancid and inedible as zebra fat or horse fat.” And then he casually mentioned that most salami is made from horse meat. Jules blanched in horror, and hasn’t had a slice of the stuff since.

Chris Baas hailed from the Damaraland area up north, which was still on our itinerary. Even though Moose from Solitaire loved the starscapes down here, Chris said the Damara skies were even brighter.

“When I take my leave every two months, I don’t head for city lights,” he said. “I head for the skylights of Damaraland.”

As we chatted and sipped coffee, Chris occasionally added bits and pieces to his potjie, done in layered style, which was how the German amateur photographers preferred it. First in was the bacon, followed by the warthog pieces, water, carrots, dill, parsley and marrows.

Deon, however, was waiting to drive us around the farm, so we left Chris wielding an enormous wooden spoon like an assegai as he showed Chef Lebeus Shimonga the finer points of venison-stewing.

For my money, there’s not an antelope to beat the oryx (also called the gemsbok or Oryx gazella). He’s a stately fellow, standing out like a Royal Guardsman in the deep brown tones of a dune or prairie. So when Deon took us to a herd of 30 oryx in the early evening light, with the Naukluft Mountains turning mauve in the background, we had to take a moment.

This was just before the mating season, and a certain hierarchy was being established. Half-serious jousting was the order of the day, and scimitar horns caught the dying sun as they flashed this way and that, like long spears held aloft by knights in a tilt contest. Someone wise once told us that if you could teach the oryx how to pad up, he’d be the greatest cricketer on earth.

“He’s able to bat stones away with his horns, no matter how fast they come at him,” the sage person said. And we’ve never heard that statement challenged.

The oryx relishes these dry, hot lands.

On a hot day, you’ll find him on the crest of a sand dune catching the coolest breeze around. He’ll hang around in shade by day and feed by night, when the plants give up their moisture. His brain temperature is cooled by a network of blood vessels situated beneath the brain. He pants fast, cooling blood in his nasal sinuses. And besides all that, he looks simply majestic – even in the middle of a killer drought.

Before coming to work on the 17 000-hectare reserve, Deon van der Berg worked as a mechanic in the northern mining town of Tsumeb. We asked him if he had a sweetheart.

“No,” he replied, and then added into the patch of silence:

“But I do have a bakkie and a horse.”

He took us up to Marble Mountain for sundowners. It was a long, fine-grained, wind-cut ridge of white and pink marble. This was also where the lodge’s water came from, so sweet that it was bottled and sold on the open market.

The full moon rose like a silver coin over the rusty Naukluft Mountains. Among the dunelands to the west, the sunset had left a cloud with a neon-gold fringe. We toasted the moonrise with a lager and then drove back in the dark to our tender potjie supper.

As we dropped off our camera gear, a stunningly elegant Japanese model walked in, surrounded by photographic staff and guides. They’d been doing a nude magazine shoot in the dunes of Sossusvlei, one of the amateur German photographers confided in us.

“But very tasteful,” he added.

In my earlier, more coltish globetrotting days, I used to think Japanese tourists hung about in shy gaggles on trainer-wheel travels. That may have been the case back then, but it seemed to have changed. Now they white-watered in tuxedos, hiked 200 km into deserts and lay naked (tastefully, it must be added) on sand dunes in the middle of the day. Respect. I even heard about some of them riding their off-road motorbikes through the Nullarbor Desert of Australia. Double respect.

The next day we said goodbye to lodge staff and korhaan clan and swung by Solitaire once again to pump some air into a suspect tyre. Moose couldn’t get the air pump to register the tyre pressure so we said goodbye, see you one day soon, and headed off into Henno’s World.

During World War II, South West-based geologists Henno Martin and Hermann Korn avoided internment by escaping with their dog Otto into the depths of the Kuiseb Canyon for nearly three years. I’d read Henno’s classic account called The Sheltering Desert and was deeply impressed by their day-to-day survival techniques. Back at the Namib Naukluft Lodge, Chris Baas had given us precise instructions on how to get to their first hideout in the canyon.

As we took the winding road into the heart of the canyon, Jules spotted a lone Hartmann’s mountain zebra on a rocky ridge gazing down at us. We passed an old truck that had rolled off a low bridge, crested the canyon and looked down over spectacularly stark views. I wouldn’t have survived a week out here. Not without a Woolworths. Or, at least, a Solitaire and a Moose.

We found the unmarked road leading to a car park. Following a sign, we walked nearly 2 km on a narrow mountain pass to the legendary shelter, Carp Cliff. The rock formations all around us were conglomerates, studded with river pebbles like fruitcakes stuffed with raisins. It must have been a perfect environment for two people so fascinated by geology.

“This is where they prepared their suppers,” Jules indicated an old ring of rocks around what looked like the remains of an ancient fire. We both eased ourselves onto a rock and talked about this amazing story.

In most of the chapters of The Sheltering Desert, Henno seems obsessed with the search for food, adequate shelter and water. But when you put yourself in their place, you realise that nothing else really matters when you’re out here.

You exult with Henno, his buddy and his dog as, nearly starving, they come across a wild steer, shoot it and begin the laborious process of butchering such a large animal.

“For weeks, all they ate was red meat,” said Jules. And then we both remembered our recent protein overdose and shuddered. Just, I suppose, as Henno and Hermann shuddered after a while at the sight of yet another Texas-sized steak (Otto the dog, obviously, chomped bravely on).

Then they both have a sugar craving of note, and out here there’s no rushing off to an all-night convenience store for Mars Bars. So they give themselves each a tiny block of their precious chocolate and go in search of bees and, ultimately, honey.

Henno and Hermann also made a net of sorts and went carp fishing at a nearby pool, thus avoiding the prospect of yet another mouthful of red meat. Up there, they somehow established a garden that yielded radishes and “mangelwurzel tops”.

“I imagine mangelwurzel to be some kind of German turnip,” said Jules and I left it at that.

They set up a radio and listened to the war broadcasts at night. This month it was one-love to Germany, the next the Allies scored on the rebound, and so on. It must have all sounded quite silly to the two canyon refugees as they watched the shooting stars go back and forth in the night skies. And chewed another strip of biltong.

“Speaking of which, don’t you think it’s time we headed for Swakop?” urged my wife. We had almost no clean clothes left, the bakkie needed a new air filter and my cameras had to be checked in for medical treatment because they had a bad case of dust on the sensors.

On into the desert we drove, towards Swakopmund. The earth levelled out into flat ochre-monotony. Yet there, in the distance, we saw an oryx, looking ready for a fight.

On what we liked to call Kudu FM, they were playing some Crowded House, Simple Minds and Spandau Ballet. I fiddled with the knob and found Dolly Parton singing Jolene on Radio Strudel (the German service). I switched over to NBC, the national broadcaster, to find we’d just missed our weekly horoscope – Gemini. At a pinch, however, sensible travellers happily listen to someone else’s horoscopes:

“Those born under Leo,” the voice intoned, “are advised to connect with their inner selves, and avoid quarrelling with their partners over money.”

“Let’s go back to Dolly,” Jules begged, and who was I to refuse her?