The Network

Before tackling the domain of braiding, which I define as beyond breakdown, it is advisable to say a word about that which comes before the layout, which I propose to give the name gridding. It is an operation (or at least a stage of reflection that is not always incarnated) that intervenes very early in the process of elaboration in comics; it defines the apparatus of the comic prior to its actual appearance. Gridding consists of dividing the available space into a number of units or compartments. While remaining in question, it operates as a primary repartition of the narrative material.

At the level of the total space of the work (for example, that of an album), gridding starts at the instant where the writer divides the work into chapters or sequences, when he seeks to evaluate their respective lengths (in the number of pages). In the hands of the illustrator this can materialize in the elaboration of a complete storyboard, or in the form of thumbnail sketches of each of the pages. Gridding is therefore an approximate equivalent of what is known as preproduction in the cinema, an end-to-end layout of the shots. It is with this essential difference that comics begin where cinema ends: the nature of the finished form does not allow the illustrator to produce images without some preliminary knowledge of their location in space and their location in the story.

Applied to the manufactured unit that is the page, gridding corresponds to the moment of taking possession of the original space. The operation, as I have said, can remain purely mental and may not have a genuine graphic translation. It can also be realized in a sketch or a grid, which would have a double virtue: to overcome the intimidating effect of the blank page, and to announce the emergence of the drawing.

Thus, for Hergé, this consisted of tracing, on a draft page, three horizontal lines divided into four strips of more or less equal importance, in which a suggestion of the breakdown could be developed. This is handed down to us by the moving testimony of the forty-second (and last) page of sketches from Tintin et l’Alph’Art (Casterman 1986) where, under a completed first strip, the second is only started and the last two remain untouched.

Gridding, therefore, defines the first, and often crudest, configuration of the multiframe. This provisory configuration furnishes the author with a framework, a matrix. The page layout becomes an improved and corrected version of the gridding: that is to say the version informed by the precise contents and by the two other constitutive operations of arthrology, the breakdown and (if the case arises) the braiding.

It sometimes happens that the contents obey a strict periodization imposed by the narrative program. Thus, gridding is revealed as an essential operation, which aims to assign to each story sequence a part that is determined by the support. Dessous troublants (Futuropolis 1986), the album by Jeanne Puchol, provides us with a good example. The action is concentrated in an apartment composed of four rooms: bedroom, office, kitchen, and washroom. Each room is evoked through four characteristic objects (thus for the office: a book, an armchair, a lamp, a pen). The number four governs the narrative breakdown, the sequences, each consecrated to the exploration of one of the rooms, each counting four pages; a door appears that effectuates the transition to the next room in the last panel of the fourth page. Finally, the epilogue of this twenty-page album consists of four pages, which makes us successively return through each of the four rooms. As simple as it is efficient, gridding—as shown here: the division of the story into five sequences (4 + 1) of the same length—furnishes a global matrix, within which the apparatus for the page layouts are constantly renewed.

Less commonly used than the concepts of breakdown and page layout, the idea of braiding, which I briefly introduced in a special issue of CinémaAction published in summer 1990,1 has nevertheless known, since its debut, some critical fortune. The time has come to give it a little more precision.

It has been often repeated in these pages that within the paged multiframe that constitutes a complete comic, every panel exists, potentially if not actually, in relation with each of the others. This totality, where the physical form is generally, according to French editorial norms, that of an album, responds to a model of organization that is not that of the strip nor that of the chain, but that of the network.

Jan Baetens and Pascal Lefèvre have justly noted that “far from presenting itself as a chain of panels, the comic demands a reading capable of searching, beyond linear relations, to the aspects or fragments of panels susceptible to being networked with certain aspects or fragments of other panels.”2 Braiding is precisely the operation that, from the point of creation, programs and carries out this sort of bridging. It consists of an additional and remarkable structuration that, taking account of the breakdown and the page layout, defines a series within a sequential framework.

It is important here to clearly distinguish the notion of a sequence and that of a series. I recall, without modification, the definitions that I gave at Cerisy in 1987:

A series is a succession of continuous or discontinuous images linked by a system of iconic, plastic or semantic correspondences. . . . A sequence is a succession of images where the syntagmic linking is determined by a narrative project.3

(As well as being infra-narrative, the notion of the series is already opposed to that of the suite, which designates a collection of disparate uncorrelated images. Apart from the fact that they initially stem from a mathematical terminology, these terms have a frequent usage in the history of art and aesthetics. For example, “Suite, series, sequence” is the title of a page by the writer Hervé Guibert, whose definitions barely differ from mine.4 It is also the title of a volume collecting the acts of a symposium organized by the University of Poitiers and the Collège International de Philosophie.)5

The series that give birth to braiding are always inscribed within narrative sequences, where the first sense, independent of the perception of the series, is sufficient in itself. The series is inscribed like an addition that the text secretes beyond its surface. Or, to put it in another way: Braiding is a supplementary relation that is never indispensable to the conduct and intelligibility of the story, which the breakdown makes its own affair.

Contrary to breakdown and page layout, braiding deploys itself simultaneously in two dimensions, requiring them to collaborate with each other: synchronically, that of the co-presence of panels on the surface of the same page; and diachronically, that of the reading, which recognizes in each new term of a series a recollection or an echo of an anterior term. A tension can be established between these two logics, but far from ending in conflict, it resolves itself here in a semantic enrichment and a densification of the “text” of the comic. (The term braiding is inscribed in the topos that habitually associates notions of tissue or threads with the text.)

By its nature, a story develops in length in a linear and irreversible manner. Inherent to all narration, this progression finds itself reinforced by the printed form, the “bookish form” (mise en livre) of the comic. As Jan Baetens writes, “the book itself induces an undeniable vectorization of discourse; the book consecrates a linear, or more exactly monovectorized, reading, that distinguishes (and sometimes discriminates) a start and an end, an incipit and an explicit, a first and a last of the cover.”6

With respect to comics, this disposition finds itself constantly embattled, and in a certain measure neutralized, by the properties that we have seen in the panels. The network that they form is certainly an oriented network, since it is crossed by the instance of the story, but it also exists in a dechronologized mode, that of the collection, of the panoptical spread and of coexistence, considering the possibility of translinear relations and plurivectoral courses.

To put it in the vocabulary of Michel Tardy, reading in this case is the operation that puts into tension the plane of the process and the plane of the system.7 The panels of the disseminated series only form a constellation to the degree that the reading detects and decrypts their complementarity and interdependence. It is the very efficiency of braiding that incites this crazed reading.

Within the network, each panel is equipped with spatio-topical coordinates by the page layout that constitutes it as a site. These temporal (or chrono-topical) coordinates are themselves conferred by the breakdown. Braiding overdetermines the panel by equipping coordinates that we can qualify as hyper-topical, indicating their belonging to one or several notable series, and the place that it occupies.

As it is articulated to several of its likenesses by a relation that comes under the jurisdiction of braiding, the panel is enriched with resonances that have an effect of transcending the functionality of the site that it occupies, to confer the quality of the place. What is a place other than a habituated space that we can cross, visit, invest in, a space where relations are made and unmade? If all the terms of a sequence, and consequently all the units of the network, constitute sites, it is the attachment, moreover, of these units to one or more remarkable series, that defines them as places. A place is therefore an activated and over-determined site, a site where a series crosses (or is superimposed on) a sequence. Certain privileged sites are naturally predisposed to become places, notably those that correspond to the initial and final positions of the story, or the chapters that compose them. (Thus, in Little Nemo, a serial where each weekly page was a chapter in itself, the final panels constitute a remarkable collection of the hero’s awakenings.) But other places do not coincide with any privileged sites; it is the effect of braiding that brings them to our particular attention and constructs them as places.8

It is now time to give some examples of these remarkable structures that define a series. I will not attempt to sketch a typology of the specific diverse procedures of braiding here, as they would no doubt be impossible to enumerate. I will content myself with demonstrating several of them, across examples presented in the rising order of their amplitude, that is to say, the distance separating the terms of the series.

The strip, the page, the double page, and the album are nested multiframes, systems of increasingly inclusive proliferation. The first three have an essential property in common: They allow a dialogue in praesentia, a direct exchange between images that are in a situation of co-presence under the gaze of the reader. While if a panel from page 5 maintains a privileged relationship with a panel belonging to page 6 on the reverse side, or with a panel from page 27—as a simple example, imagine that the second panel is a reproduction of the first—this relation establishes itself in absentia, at a distance. The correspondences handled by braiding frequently concern panels (or pluri-panel sequences) distant by several pages, and that cannot be viewed simultaneously.

Let us note that no panel can be integrally repeated without modification. The reprise of the same panel at two locations in a comic, contiguous or distant, does not constitute a perfect duplication. The second occurrence of the panel is already different from the first by the sole fact of the citation effect that is attached. The repetition raises the memory of the first occurrence, if it is a matter of a rhyme (distant repetition),9 or manifests a singular insistence, if the two occurrences are contiguous. But most important is that, being isomorphs, these panels cannot be “isotopes”; by definition, they cannot occupy the same site. Even if it is not the object of a particular qualification (which is assuredly not the case if there is a rhyme), the site is an inalienable constitutive parameter of the panel.

An example that is both simple and famous is the triptych that occurs on page 35 of Tintin in Tibet, when Tintin and his friends, having given up trying to find Chang, abandon the carcass of the downed plane and prepare to leave. At this point in the story, the breakdown seeks to evoke the slow and derisory progression, in a vast snowy expanse, of protagonists reduced to the dimension of ants, in three contiguous panels. Braiding pulls on part of this contiguity to institute a continuity in the representation of the décor, which takes on the aspect of a large panorama; in the background, the circle of mountains is prolonged in all three of the contiguous panels. Not only does this relatively elementary braiding operate in praesentia, relying on panels offered as an ensemble at a glance, but the entire series draws a compact form and a linear suite.

Somewhat tempering the structuralist euphoria of the epoch, Georges Mounin observed not long ago that “a structure . . . holds interest only if we can show that it has a precise function in the work, that it is pertinent (and at which point of view it is).”10 This methodological requirement naturally applies for series that produce braiding. At its occurrence, the narrative pertinence of the Hergéan apparatus leaps out: widening the décor magnifies the immensity of the region to be explored in order to eventually find Chang, dooming the hero’s quest to failure.

In La Orilla, the two-page mute story by Frederico Del Barrio analyzed earlier (cf. 1.6, fig. 3), braiding identifies itself as an effect of plastic composition. It is the localization of the character in the image that is the agent. These successive positions draw a descending diagonal, and, symmetrically, an ascending diagonal, thus inscribing a giant V at the heart of the story.

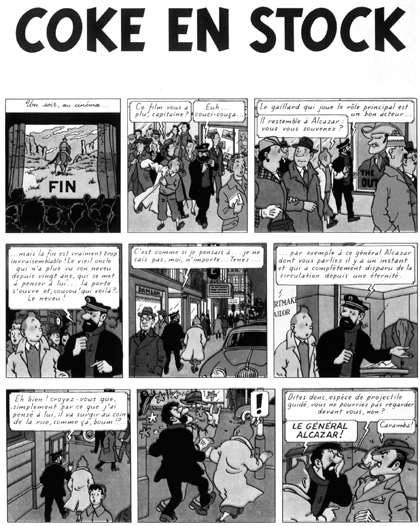

The inaugural page of The Red Sea Sharks (fig. 13) was the subject of a brilliant analysis by Jan Baetens, who brought to light a remarkable series, that of the three Alcazars.11 I will repeat the demonstration: the name of General Alcazar is cited three times, in the last panel of each of the three strips. The first of these panels shows a poster representing an actor that resembles the General; the third of these panels marks the appearance of the actual Alcazar, but an Alcazar whose gaudy civilian elegance, considering the fact that he is a military man, appears to be in disguise. The passage of the pseudo-Alcazar to the real one is effectuated through the headless mannequin that occupies the intermediate panel at the end of the second strip. The location of these three figures, always to the right of Tintin and the Captain, and the permanence of the repeated colors in the clothing (red and green) sufficiently attest that they behave as a concerted series.

Fig. 13. From The Adventures of Tintin: The Red Sea Sharks (1958) by Hergé. © Moulinsart S.A.

This series creates a compact, in the sense that the three panels are contiguous. But, distributed along a vertical axis, they are linked in a translinear manner, straddling other panels that are not concerned with the effect of braiding but which share the rest of the page. We must therefore emphasize that braiding invests these sites as doubly privileged: first because it is an inaugural page, further because the three panels occupy corresponding places at the different levels of the page.

Instead of this remarkable series, what the reader cannot help but notice in the page is evidently the fact that the album opens on a panel that contains the words “THE END.” The two phenomena (the paradox of this introductory inscription, and the braiding that sets the stage for the first appearance of Alcazar) are not to be dissociated. It has been little remarked that the inscription “START” can be found symmetrically in the last panel of the album (in a more discreet fashion, it is true). But the end to which the incipit points cannot be only that of the entire work, but also of the page itself, designated in anticipation as a privileged place. To the cinematographic image of a horseman riding away peacefully, can we not oppose the image of the General, who himself arrives in a violent manner?

Everyone has in their memory the scene at the start of The Shooting Star, where Tintin arrives at the observatory and discovers, through the telescope, a gigantic spider that seems to be attached to the asteroid that is approaching the Earth. This panel occupies the right side of the second strip of page 4. Tintin soon understands that it was nothing more than a small spider magnified by the telescope. He can then directly contemplate the asteroid, without the interposition of this disruptive intrusion. Thus, this second glance through the telescope occupies the panel situated to the right of the second strip of page 5, which is printed face to face with its precedent.

It suffices to examine the album for verification: The recurrence of the “ball of fire” observed by the telescope is much more striking because the two coupled panels have the same spatio-topical coordinates within their respective pages. The rhyme effect is considerably reinforced, so well that the disappearance of the spider (elsewhere called to reappear throughout the album under diverse forms) has the force of an immediately perceptible visual event. Braiding, once again, makes these naturally corresponding sites work.

As the two examples borrowed from Hergé illustrate, braiding is generally founded on the remarkable resurgence of an iconic motif (or of a plastic quality), and it is concerned primarily with situations, with strong dramatic potential, of appearance and of disappearance.

In adapting The Masque of the Red Death by Edgar Allan Poe, Alberto Breccia systematized translinear relations in absentia between corresponding sites of consecutive pages. The action is situated in the palace of Prince Prospero, which Poe fittingly described in these terms: “These windows were of stained glass whose color varied in accordance with the prevailing hue of the decorations of the chamber into which it opened.”12 In the fourth page of the story, Breccia shows us the open orgies in all the rooms of the palace, while outside the palace walls the plague ravages the country. But, at the stroke of midnight, the “Red Death” penetrates through to the prince, in the appearance of a spectre, interrupting the festivities. The spectre, Poe tells us, “made his way uninterruptedly . . . through the blue chamber to the purple, through the purple to the green, through the green to the orange, through this again to the white, and even thence to the violet, ere a decided movement had been made to arrest him. It was then, however, that the Prince Prospero, maddening with rage and the shame of his own cowardice, rushed hurriedly through the six chambers. . . . He bore aloft a drawn dagger.”

This sequence is translated by Breccia into two consecutive pages, the eighth and ninth of a twelve-page story (fig. 14). The crossing of the six rooms is materialized by the repetition of the same character. In spite of some minor variations in the silhouette, it appears frozen in a hieratic posture and endowed with ubiquity. Time and action seem suspended, as if the same instant found itself eternalized by a means of diffraction. The same procedure is applied successively to the spectre, then, in the following page, to the prince. The two characters never appear within the same image in this sequence (or even on the same page); the theme of the pursuit of one another across all the rooms in the palace seems to be elided. While it does not accede to a direct representation, the theme of pursuit is accomplished only by relating, two by two, the twelve implicated sites, namely the recognition of six chromatically differentiated series. (The two pages in question have sometimes been printed face to face, and sometimes not, depending on the edition.)

The spider in The Shooting Star, or the yellow badge in Watchmen, are two classic examples of motifs where the proliferation throughout the works, as appearances at essential moments in the story and/or naturally privileged sites by the book, produces rhymes and remarkable configurations. The texturing of intrigue, which is accomplished through the recurrence of these emblems, is itself accompanied with a considerable symbolic richness.

Fig. 14. From Le masque de la mort rouge (1982), by Alberto Breccia, adapted from the story by Edgar Allan Poe. © Alberto Breccia.

Watchmen, the work by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons that has already been cited several times in these pages, counts more than three hundred pages and makes intense use of all the procedures of braiding. It is notably structured by a declension of the figure of a circle, used both as a recurrent geometric motif that lends itself to plastic rhymes, and for its symbolic connotations (perfection, eternal recommencement, etc.). One of the occurrences of the circle that contributes in this way is the smiling badge, familiarly designated under the names happy face or smiley. The authors have contrived to put in place two narrative loops, the first circumscribed by the inaugural chapter, the second extending to the dimension of the entire work.

Indeed, the famous badge appears right in the first panel of the first chapter, and in the last panel of this same chapter, as well as in the last panel of the twelfth and final chapter. A remarkable relationship is established between these antithetical locations, predisposed to correspond under the emblem of circularity and through the use of style. (The relationship put into place by Moore and Gibbons is much more elaborate than the little bit that we have just looked at.)

There are other examples of the proliferation of a motif, in which it obeys only a sort of playful formalism. I’m notably thinking about the multiplicity of black circles and ovals in Yann and Le Gall’s album, La Lune noire (Les exploits de Yoyo, t. 1., Glénat 1986).

Once a graphic motif spreads across the entirety of the network that composes a comic, it can arouse several thematically or plastically differentiated series. Braiding therefore becomes an essential dimension of the narrative project, innerving the entirety of the network that, finding itself placed in effervescence, incites translinear and plurivectoral readings. We know of films structured in an analogous fashion; for example, Orson Welles’ Macbeth is entirely organized, as Jean-Pierre Berthomé has shown, “around the two motifs of the Celtic cross and pitchforks which incessantly recur, they meddle and affront, each affirming their pretension to invade space.”13 But, barring the use of a video or DVD, the vision of the film is, by definition, monovectorized and irreversible; the filmic images are fugitive, and the echo of an image already passed is without another reality, no verification is possible, other than that of memory.

Upon first reading, the seventeenth page of the first album of the series Sambre by Yslaire and Balac (fig. 15) is surprising. It seems that nothing happens, outside of the apparition (again!) of a light in an otherwise dark room. The long and complex “movement of the apparatus,” beyond the small forest, leads us to the familial home of the Sambres, nearby the cemetery where the father has just recently been buried. If it marks a remarkable pause in the action, it is certainly not a vain parenthesis. It represents a superb case of braiding, which I have chosen as my final example.

The Z path that the eye must accomplish to sweep over the seven panels that compose this page is highlighted entirely by the succession of circular motifs. The round window seen in close up in the first panel is visible in the second image, from much further away, just under the roof; afterward, the path hooks onto the white stain made by the moon, three times repeated along a senestro-descendent diagonal; to reach the bottom left side of the page, the path must return to the window, now lit, which inevitably makes us see the rosette, pierced by a clover-leaf opening that adorns the Sambre tomb.

In multiplying the circles and distributing them to eminently concerted spaces, the authors have not ceded to the temptation of a simple formalism. Here, the series of circles bears meaning: they speak to us of imminent justice and power, through the metaphor of the eye that sees, that knows, and that judges. Indeed, this window, whose name in the vocabulary of the architecture is “bull’seye,” belongs to the office of Hugo Sambre, the absent father. As for the familial motto inscribed on the front wall of the tomb, it is worded: “Sambre, the light of the moon looks upon you.” If the moon is looking, we must deduce that it is equipped with eyes, or is considered to be an eye itself. This eye in the sky that watches the intrigues of the Sambres can only be that of the father. In leaving his office, he merely changed his place of observation, taking it to a higher level. His point of view is now confounded with that of God. For a character buried in 1848, and that holds the name of Hugo, it is hard not to think of the celebrated poet of the same name: “The eye was in the tomb, and was looking at Cain.”

In the last panel, if the office is newly lit, it is because, as the following page attests, Sarah, the daughter of the deceased, has just moved inside. By taking possession of this room, she intends to establish her moral authority over the family, taking on the responsibilities of her father. She installs herself to work as well, having decided to recopy and complete the unfinished manuscript left by Hugo Sambre, a manuscript entitled The War of the Eyes. (The preceding page had already concluded with a close up of Sarah shooting the reader a livid stare. Her eyes justly occupy the same site as the bulls-eye that, now lit, reveals her presence.)

Fig. 15. From Sambre #1: Plus ne m’est rien (1986), by Yslaire et Balac. © Éditions Glénat.

Simply through a game of formal analogies a rather powerful semantic network is put into place that will later be revealed as rich in narrative consequences and symbolic implications. In this page alone we see the tying together of themes that will nourish the entirety of the work in several volumes, in particular that of the eye. I will quickly cite three other pages that, far from them being exhaustive, sufficiently attest to the repercussions of the series put into place, and to the extension given to the procedure of braiding that, in this comic, exerts a veritable imperialism on intrigue and the sequential breakdown.

Page 7 of Book 1: Julie, the poacher, the heroine of this tragedy, has red eyes, a sign of her allegiance to a cursed race that has been predicted to cause the ruin of the Sambres.

Page 37 of Book 1: the moon returns in an oneiric scene, and it returns in an explicit liaison with the idea of justice and punishment.

Page 46 (the last page) of Book 2: finally, the moon again, but this time red like the eyes of Julie. Pregnant with the seed of Bernard Sambre, Julie will deliver a new life. The bloodied moon announces, for Julie, the imminence of the revolution, which represents the hope of a new and better life for the people of Paris.

Braiding thus manifests into consciousness the notion that the panels of a comic constitute a network, and even a system. To the syntagmatic logic of the sequence, it imposes another logic, the associative. Through the bias of a telearthrology, images that the breakdown holds at a distance, physically and contextually independent, are suddenly revealed as communicating closely, in debt to one another—in the manner that Vermeer’s paintings, when they are reunited, are perceived to come in pairs, or in threesomes. As Pierre Fresnault-Deruelle justly noted, it is these “thousand and one forms of deviation and correspondence that makes of comics a text in the strongest sense of the term.”14