8. SUFISM IN INDO-PAKISTAN

THE CLASSICAL PERIOD

The western provinces of the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent had become part of the Muslim Empire in 711, the year in which the Arabs conquered Sind and the adjacent provinces northward up to Multan.1 The Muslim pious in these areas were, in the early centuries, apparently interested mainly in the collection of ḥadīth and in the transmission to the central Muslim countries of scientific information from India (mathematics, the “Arabic” numbers, astronomy and astrology, medicine), but their religious feelings may sometimes have reached the heights of mystical experience. Spiritual contacts between the Muslims and the small Buddhist minority, as well as with the large group of Hindus (who were slightly outside the main current of orthodox Hinduism), may have existed, though earlier European theories that tried to explain Sufism as an Islamized form of Vedanta philosophy or of Yoga have now been discarded. In 905, a mystic like Ḥallāj traveled extensively throughout Sind and probably discussed theological problems with the sages of this country.2

The second wave of Muslim conquest in India, that of the Ghaznawids about the year 1000, brought into the Subcontinent not only scholars like al-Bīrūnī (d. 1048), who made a careful study of Hindu philosophy and life, but theologians and poets as well. Lahore became the first center of Persian-inspired Muslim culture in the Subcontinent—the name of Hujwīrī, who composed his famous Persian treatise on Sufism in this town, has already been mentioned; his tomb still provides a place of pilgrimage for the Panjabis.

The full impact of Sufism, however, began to be felt in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, after the consolidation of the main Sufi orders in the central provinces of Islam. The most outstanding representative of this movement is Muʿīnuddīn Chishtī, born in Sistan and part-time disciple of Abū Najīb Suhrawardī. He reached Delhi in 1193,3 then settled in Ajmer, when the Delhi kings conquered this important city in the heart of Rajputana. His dwelling place soon became a nucleus for the Islamization of the central and southern parts of India. The Chishtī order spread rapidly, and conversions in India during that period were due mainly to the untiring activity of the Chishtī saints, whose simple and unsophisticated preaching and practice of love of God and one’s neighbor impressed many Hindus, particularly those from the lower castes, and even members of the scheduled castes. The fact that the Chishtī khānqāhs avoided any discrimination between the disciples and practiced a classless society attracted many people into their fold. Muʿīnuddīn reduced his teaching to three principles, which had been formulated first by Bāyezīd Bisṭamī (T 1:164): a Sufi should possess “a generosity like that of the ocean, a mildness like that of the sun, and a modesty like that of the earth.” Although the type of the soldier-Sufi, the fighter for the true religion, is sometimes found in the frontier provinces of India, as it is in other border areas between Islam and the land of the infidels,4 the Islamization of the country was achieved largely by the preaching of the dervishes, not by the sword.5

When Muʿīnuddīn died in 1236—not far from the beautiful mosque Quṭbuddīn Aybek of Delhi had erected in Ajmer—he was succeeded by a large number of khalīfas, who made his ideals known all over India. To a certain extent, the sphere of influence of a khalīfa was designated by the master, who determined the areas where the baraka of this or that disciple should become active—a territorial distribution of spiritual power frequently found in Indian Sufism.

Even today the tomb of Quṭbuddīn Bakhtiyār Kākī from Farghana, who came to India together with Muʿīnuddīn, is frequently visited. This saint, who died in 1235, was highly venerated by Iltutmish, the first king of the Slave Dynasty of Delhi, and the rather modest compound in Merauli near the Qutb Minar in Delhi is usually filled with pious pilgrims, who recite and sing their devotional poetry. The beautiful marble sanctuary of Muʿīnuddīn (erected by the Mogul Emperor Jihangir) is also still a center of religious inspiration for thousands of faithful Muslims.

Bakhtiyār Kākī’s successor was Farīduddīn (d. 1265), but because of the politically confused situation he left the capital and settled in the Punjab on the river Sutlej.6 His home has been known, ever since, as Pakpattan, “the ferry of the pure.” Farīd had been influenced in his early religious life by his pious mother. He performed extremely difficult ascetic practices, among them the chilla maʿkūsa, hanging upside down in a well and performing the prescribed prayers and recollections for forty days. His constant fasting was miraculously rewarded—even pebbles turned into sugar, hence his surname Ganj-i shakar, “sugar treasure.” Whether this charming legend is true or not, it shows the extreme importance Farīd placed on ascetic exercises, and we may well believe that “no saint excelled him in his devotions and penances.” Even his family life suffered under the restrictions he placed upon himself. He did not care for his wives or children, eight of whom survived. When he was informed that a child had died—so legend has it—he said: “If fate has so decreed and he dies, tie a rope around his feet and throw him out and come back!” This tradition reminds the historian of the attitude of some of the early ascetics, who rejoiced at the death of their family members. But as a consequence of this inhuman attitude, most sons of early Chishtī saints turned out to be worldly people, some even drunkards, who had no disposition at all for the religious, let alone mystical, life.7

The maintenance of Farīduddiīn’s khānqāh—and he is mentioned here as an outstanding example of the early Chishtī way of life—was difficult, since the sheikh relied exclusively upon gifts (futūḥ), and the khānqāh did not own or cultivate land from which the dervishes might draw their living. No jāgīrs (endowments of land) or grants from the rulers were accepted by the Chishtīs, for they refused to deal with the worldly government. One of their poets said:

How long will you go to the doors of Amirs and sultans?

This is nothing else than walking in the traces of Satan.

This mistrust of government, familiar from early Sufi literature, became more outspoken with these Chishtī saints, who considered everything in the hands of the rulers to be unlawful.

The dervishes in the khānqāh regarded themselves as “guests of God,” living and working in one large room; visitors were always welcome, and the table always spread for unexpected guests—if there was any food available. The residents had to serve the sheikh and the community, and their main occupations were prayer, worship, and the study of books of devotion and the biographies of saints. Farīduddīn and his fellow saints in the order, however, recommended a good education for the disciples and were interested in poetry and music. It is possible that Farīduddīn composed a few lines of poetry in the local dialect, which would place him in the chain of those mystics who helped disseminate Sufi teachings in popular songs, thus influencing the population, particularly the women, who used to sing these simple verses while doing their daily work.

Farīduddīn invested seven khalīfas with spiritual power; among his disciples, Jamāl Hānswī and Niẓāmuddīn must be counted as his special friends. The poet Jamāl Hānswī (d. 1260) wrote moving mystical songs in Persian—unsophisticated and sometimes slightly didactic, but attractive. Farīduddīn’s outstanding khalīfa, however, was Niẓāmuddīn, whom he met in 1257, only a few years before his death.

Niẓāmuddīn was one of the well-known theologians of Delhi; then, with his master, he studied Suhrawardī’s ʿAwārif al-maʿārif, the guidebook of almost all the Indo-Muslim mystics in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. After his third visit to Pakpattan, he was appointed khalīfa in Delhi. The name of Niẓāmuddīn Auliyāʿ, “Saints,” as he came to be known out of respect, marks the high tide of mystical life in Delhi. The saint was a strict follower of the Prophetic sunna, a student of and commentator on the Prophetic traditions, and, at the same time, a friend of poets and musicians. Baranī, the Indo-Muslim historiographer of the early fourteenth century, claims that it was Niẓāmuddīn’s influence that inclined most of the Muslims in Delhi toward mysticism and prayers, toward remaining aloof from the world. Books on devotion were frequently sold. No wine, gambling, or usury was to be found in Delhi, and people even refrained from telling lies. It became almost fashionable, if we are to believe Baranī, to purchase copies of the following books: Makkī’s Qūt al-qulūb and, quite logically, Ghazzālī’s Iḥyāʾ ʿulūm ad-dīn; Suhrawardī’s ʿAwārif al-maʿārif and Hujwīrī’s Kashf al-maḥjūb; Kalābādhī’s Kitāb at-taʿarruf and its commentary; and the Risāla of Qushayrī. Also in Baranī’s list are Najmuddīn Dāyā’s Mirṣād ul-ʿibād, the letters of ʿAynuʾI-Quḍāt Hamadhānī, and, the only book written by an Indian Muslim, Ḥamīduddīn Nagōrī’s Lawāmiʿ, a treatise by one of the early Chishtī saints (d. 1274) noted for his poverty and his vegetarianism. These books may have given succor to the population in the confused

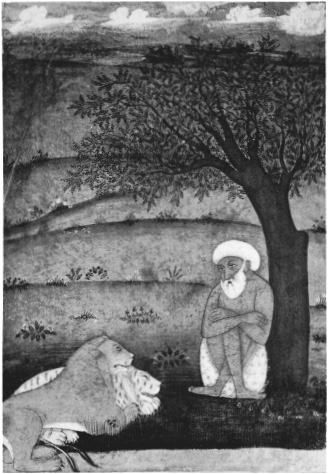

A saint with his tame lions, Indian, early seventeenth century. - Staatliche Museen, East Berlin

political situation. Niẓāmuddīn Auliyā (d. 1325), tenderly called by his followers Maḥbūb-i ilāhī, “God’s beloved,”8 outlived seven kings, and constant intrigues, bloodshed, and rebellions took place in Delhi and its environs during his life.

During Niẓāmuddīn’s time, Sufism became a mass movement in northwestern India, and the moral principles laid down by the early Chishtī saints did much to shape the ideals of the Muslim society in that part of the Subcontinent. A number of Punjabi tribes still claim to have been converted by Farīduddīn Ganj-i Shakar.

Close to Niẓāmuddīn’s tomb in Delhi—still the most frequently visited sanctuary in Delhi—is the tomb of his closest friend and disciple, Amīr Khosrau (1254–1325), the best-known poet of the early Muslim period in India. Versatile and witty, he composed lyrics and epics, historical poetical novels, and treatises on epistolography, but almost no mystical poetry. He was, however, the founder of the Indo-Muslim musical tradition; he was a composer and a theoretician, and this talent of his certainly developed in connection with his Chishtī affiliation. Austere as they were in their preparatory stage of life, the Chishtiyya allowed the samāʿ, the spiritual concert and dance; this predilection is reflected in many of their sayings and in their poetry. They have contributed a great deal to the development of the Indo-Muslim musical tradition, of which Amīr Khosrau—lovingly styled “the parrot of India” and “God’s Turk”—was the first great representative.

Khosrau’s friend Ḥasan Sijzī Dihlawī (d. 1328)—the disciple of Niẓāmuddīn who collected his master’s sayings—is less well known as a poet, but his verses convey more of the truly mystical spirit than Khosrau’s. They are winsome in their lyrical wording, replete with love and tender emotion. About the same time, a beautiful poem in honor of the Prophet Muhammad was composed by a third poet of the Chishtiyya, Bū ʿAlī Qalandar Panīpatī (d. 1323), whose verses were the first of the many eulogies for the Prophet written in the Subcontinent. The same mystic who wrote charming lines about the all-embracing power of love—“Were there not love and the grief of love—who would say, who would hear so many sweet words?” (AP 112)—wrote some remarkable letters to the Delhi kings criticizing their way of life.

From Niẓāmuddīn Auliyā the spiritual chain goes to Chirāgh-i Dehlī, the “Lamp of Dehli” (d. 1356) and then to Muhammad Gīsūdarāz, “he with the long tresses?” who migrated to the Deccan and enjoyed the patronage of the Bahmani Sultans. This saint, who died in 1422 and is buried in Gulbarga near present-day Hyderabad, was a prolific writer of both poetry and prose in Arabic and Persian. He also composed a book on the Prophet of Islam, Miʿrāj al-ʿāshiqīn, for the instruction of the masses, in Dakhni, the southern branch of Urdu. He was the first Sufi to use this vernacular, which was elaborated upon by many other saints in southern India in the next two centuries. Gīsūdarāz was probably the first author in the Subcontinent who tried to introduce the classical works of Sufism on a broad scale; he commented upon Ibn ʿArabī’s Fuṣūṣ al-ḥikam as well as upon Suhrawardī’s Ādāb al-murīdīn and wrote numerous treatises and books on mystical life and on Prophetic traditions. Thanks to him, both the refined love mysticism of ʿAynuʾl-Quḍāt’s Tamẖīdāt and the fundamental work of Ibn ʿArabī were made accessible to Indian Sufis and came to influence the development of mystical thought in later centuries. Gīsūdarāz’s Persian poetry gracefully translates the feelings of his loving heart—intoxicated by divine love, he feels himself to be beyond separation and union. The true lovers, who quaflfed the wine of love at the Day of the Covenant,

are the first page (dibāja) of the book of existence

and have become the preeternal title of endless eternity.

(AP 152)

The Chishtiyya remained for centuries the most influential order in the Subcontinent, but it never went beyond its borders.

Another important order was the Suhrawardiyya, the tradition from which Muʿīnuddīn Chishtī had drawn his first inspiration. Several of Abū Ḥafṣ ʿUmar Suhrawardī’s disciples reached India at the beginning of the thirteenth century. Among them was Jalāluddīn Tabrīzī, who went to Bengal, where he died in 1244. The order still flourishes in this area and has produced a number of mystics and political figures among the Bengali Muslims.

An even greater Suhrawardiyya impact on Muslim religious life was made by Bahāʾuddīn Zakariya Multānī (d. ca. 1262), a contemporary of Farīduddīn Ganj-i Shakar. It is revealing to compare the style of life of these two mystics, who were separated by only a few hundred miles—the stern ascetic Farīd, who gave no thought to any worldly needs and refused all governmental grants for his family and his disciples, and the well-to-do landlord Bahāʾuddīn, who looked after the needs of his family and never failed to keep a supply of grain in his house. His accumulation of wealth was sufficient to make him the target of accusations by other Sufis, but his sons, unlike the sons of most of the early Chishtī saints, followed in his path; the succession in the Suhrawardiyya became, generally, hereditary. As opposed to the open table in the poor Chishtī khānqāhs, Bahāʾuddīn was more formal and had fixed hours for visitors who were invited to partake in meals. And he was willing to mix freely with members of the ruling classes—just as Abū Ḥafṣ ʿUmar Suhrawardī himself had served the caliph an-Nāṣir.9 This contrasting attitude toward the world, and toward its most dangerous representative, the government, has survived through the centuries. It is interesting to compare the theories of the sixteenth-century Egyptian mystic Shaʿrānī about the relations between the Sufis and the government with the utterances of the Indian saints of either tradition.

It may be that Bahāʾuddīn Zakariya would not have been so well known if a noted love poet had not lived in his entourage for nearly twenty-five years. This poet was Fakhruddīn ʿIrāqī (d. 1289).10 He had fallen in love with a certain youth and had followed him and a group of dervishes who went to India. In Multan he attached himself to Bahaāʿuddīn, to whom he dedicated some impressive qaṣīdas. The story goes:

The saint set him in a cell. For ten days ʿIrāqī sat therein admitting nobody. On the eleventh day, overcome by his emotion, he wept aloud and sang:

The wine wherewith the cup they first filled high,

was borrowed from the sāqī’s languorous eye.

The inmates of the hospice ran and told the saint what was passing. Now this order followed the rule of Shihābuddīn Suhrawardī whose favoured pupil Bahāʾuddīn was, and Suhrawardī’s rule was that the devotee should occupy himself only with the recitation of the Koran and the expounding of tradition. The other brothers therefore viewed ʿIrāqī’s behavior with disapproval, and complained to the saint. He however replied that this was prohibited to them, but not to him.

Some days later, ʿImāduddīn, passing through the bazaar, observed that this poem was being recited to the accompaniment of music. Visiting the taverns he found the same thing there. On his return, he reported this to the saint recounting what he had heard as far as the lines:

Why should they seek to hurt ʿIrāqī’s fame,

since they themselves their secrets thus proclaim!

“His affair is complete,” said the saint, and arising he went to the door of ʿIrāqī’s cell.

“ʿIrāqī,”he called, “do you make your prayers in taverns? Come forth!”

The poet came out of his cell, and laid his head at the saint’s feet, weeping. The latter raised his head from the ground, and would not suffer him to return to his cell, but taking off the mystic robe set it upon him.11

Bahāʿuddīn, with the spiritual insight of a true saint, acknowledged ʿIrāqī’s greatness and true love. The tender and intoxicating love poems that the Persian poet composed are still being sung by Pakistani musicians at the door of the master’s tomb in Multan.

ʿIrāqī’s poetic interpretation of a classic Arabic verse about the wine and the glass, indistinguishable in the light of the sun, is one of the favorite quotations of later Sufis:

Cups are those a-flashing with wine,

Or suns through the clouds a-gleaming?

So clear is the wine and the glass so fine,

that the two are one in seeming.

The glass is all and the wine is naughted,

Or the glass is naught and the wine is all.12

For the history of Sufi thought, his Lamaʿāt, “Flashes,” inspired by Ibn ʿArabī”s theories, are highly important. He dealt in the traditional Persian form of mixed poetry and prose with a number of problems of mystical life in general and of his own life in particular: with love revealed through the medium of human beauty. For ʿIrāqī, love is the only thing existing in the world (lamʿa 7), and lover, beloved, and love are one—union and separation no longer pertain (lamʿa 2). The light of the cheek of the beloved is the first thing the eye sees, His voice the first thing the ear hears (lamʿa 18), and the separation that the beloved wishes is a thousand times better and more beautiful than the union desired by the lover (lamʿa 22). Thus he goes beyond the early formulation that love means staying at the friend’s door even if sent away.

ʿIrāqī sees God, the eternally beautiful beloved, everywhere and is in love with everything the beloved does and orders. Why should he himself wish anything? Heart and love are one; love sometimes grows out of the heart like flowers, and the whole world is nothing but an echo of love’s eternal song. Although the lover is bound to secrecy, the beloved himself makes the secret of love manifest. Why, then, was a lover like Ḥallāj punished for his disclosure of the secret of divine love?

Soon after Bahāʾuddīn Zakariya’s death, ʿIrāqī left Multan for Konya, where he met Ṣadruddīn Qōnawī and perhaps Jalāluddīn Rūmī. ʿIrāqī is buried in Damascus, close to the grave of Ibn ʿArabī, whose thoughts he had transformed poetically. ʿIrāqī’s influence on later Persian and Indo-Persian poetry can scarcely be overrated; the Lamaʿāt were often commented upon, and Jāmī popularized his thoughts.

In the history of the Suhrawardiyya in India the intensity of ʿIrāqī’s experience, the splendor of his radiating love, has rarely been repeated. One of Zakariya’s disciples, Sayyid Jalāluddīn Surkhpūsh (“Red-dressed,” d. 1292) from Bukhara, settled in Ucch, northeast of Multan, and is the forefather of a long line of devout mystics and theologians. Ucch was, for a while, the center of the Suhrawardiyya, thanks chiefly to the active and pious Jalāluddīn Makhdūm-i Jahāniyān, “whom all the inhabitants of the world serve” (d. 1383), a prolific writer in almost all religious fields. It was in Ucch that the first missionaries of the Qādiriyya settled in the late fifteenth century; from there this order spread into the Subcontinent, where it soon gained a firm footing and was carried to Indonesia and Malaysia.13

Another aspect of mystical life developed in the same period during which Muʿinuddīn Chishtī and Bahāʾuddīn Zakariya were preaching divine love and union: its representative is Lāl Shahbāz, “the Red Falcon,” Qalandar. From Marwand in Sistan, he was the saint of Sehwan, who lived in the mid-thirteenth century in Sind, at the site of the old Shiva sanctuary at the west bank of the lower Indus. Lāl Shahbāz was an intoxicated mystic who considered himself a member of the spiritual lineage of Ḥallāj, as some of his Persian verses seem to show. Around his sanctuary strange groups of bī-sharʿ, “lawless,” Sufis (malang) gathered, dressed in black, and the mystical current connected with Sehwan often shows Sufism in its least attractive aspects. The “fair” of Sehwan—celebrated between Shawwal 18 and 20—has become notorious for its rather illicit events.14 A lingam close to the actual tomb proves the Shivait background of some of the rites.

The orders grew in India in the following centuries, and new suborders emerged, among which the Shaṭṭaāriyya in the sixteenth century deserves special mention. The main representative of this order—which is restricted to India and Indonesia—was Muhammad Ghauth Gwaliori (d. 1562), for whom Akbar built a magnificent tomb. This Muhammad Ghauth is the author of an interesting book, Al-jawāhir al-khamsa, “The Five Jewels,” which deals with manners and practices of Sufism and also connects the meditation of the most beautiful names with astrological ideas. This book deserves a detailed study both in its original Persian and in its widely read Arabic translation.15 Another member of the Shaṭṭāriyya, Muhammad Ghauthī (d. after 1633), composed a voluminous work about the Indo-Muslim, especially Gujrati, saints that contains biographies of 575 Sufis, As time passed, the mystics became ever more preoccupied with collecting biographical notes and making compilations of second- and often third-hand information.

The early Indian Sufis had already displayed an amazing literary activity. Although the mystics often expressed their aversion to intellectual scholarship and writing, most of them were quite eager to put down their knowledge in books and treatises. In India, a special literary genre became very popular—the so-called malfūẓāt, collections of sayings of the spiritual preceptors. This was not an Indian invention—the classical handbooks of Sufism consist to a large extent of apothegmata and random sentences of the masters of old. The Indian Sufis, however, carefully collected the dicta of their masters from day to day, and, as Khaliq Ahmad Nizami has rightly pointed out, these “diaries” constitute a valuable source for our knowledge of life outside the court circles. They are a necessary corrective of the official historiography; they allow us interesting glimpses into social and cultural problems that the official authors wittingly or unwittingly overlooked.

The first important example of this genre is the Fawāʾid al-fuʾād, Niẓāmuddīn Auliyā’s conversations compiled between 1307 and 1322 by his disciple Amīr Ḥasan Sijzī Dihlawī, the poet. Only after a year had passed did he let his master know of his scheme. From then on Niẓāmuddīn himself helped him in filling the lacunae in the manuscript. Most of the fourteenth-century mystics, whether they lived in Delhi—like Chirāgh-i Delhi (Khayr al-majālis)—or settled in central India—like the grandson of Ḥamīduddīn Nagōrī, who compiled his ancestor’s sentences (Surūr aṣ-ṣudūr)—had their sayings recorded. In later times, collections of malfūẓāt were fabricated with more or less pious intent.16

Some other mystics set out to write histories of their orders. Mīr Khurd, a disciple of Niẓāmuddīn and friend of Ḥasan Dihlawī, like him and like many leading intellectuals of Delhi forced by Muhammad Tughluq to leave Delhi for the Deccan in 1327, felt guilty about deserting his master’s sanctuary, and, as expiation for this impiety, he undertook to write a history of the Chishtī order, the Siyar al-auliyāʾ. This book is still the most trustworthy account of the Chishtī silsila and of medieval Chishtī khānqāh life.

Another literary activity was the writing of letters, partly private, partly for circulation. The collections of the letters of Muslim Indian Sufis from the thirteenth century on are an extremely important source of our knowledge of the age and movement and, as in the case of Aḥmad Sirhindī, have played a remarkable role even in politics. Sufi thought permeated all fields of poetry, and even poets who are classified primarily as court poets could reach mystical heights of expression. An example is Jamālī Kanbōh (d. 1535), Iskandar Lodi’s court poet, whose famous lines on the Prophet have already been quoted (p. 221).

By the fourteenth century, the works of Sufis of the classical period were being continuously read and explained. Though the interest was at first concentrated upon the representatives of moderate Sufism, the theosophy of Ibn ʿArabī and his disciples soon became popular in India. The number of commentaries written on the Fuṣūṣ al-ḥikam, and the number of books that were composed to explain the theories of the Great Master, are myriad. From the late fifteenth century on, Ibn ʿArabī’s ideas became influential everywhere. ʿIraqī’s and Jāmī’s poetry, which were a poetical elaboration of these ideas, made them even more popular, since many people who would not read theoretical Sufi works certainly enjoyed these lovely poems. The name of ʿAbduʾl-Quddūs Gangōhī (d. 1538), a leading saint and prolific writer, is an outstanding example of Sufism tinged by the theories of the waḥdat al-wujūd. It should, however, be emphasized that ʿAbduʾl-Quddūs strictly observed the Muslim law, as did most of the influential spiritual preceptors.17

Under the influence of the theory of “Unity of Being,” some mystics might see points of correspondence between Sufi thought and the Vedanta system of Hindu philosophy and attempt to bring about an approximation between Muslim and Hindu thought—a current that was viewed with great distrust by the orthodox.

The question of the probability and extent of mutual influences of Muslim and Hindu mysticism has been discussed often by Oriental and Western scholars. India had, indeed, been known as the country of magical practices—Ḥallāj even went there “in order to learn magic,” according to his detractors. It is small wonder, then, that Sufi hagiography in India describes magic-working contests between Sufi saints and yogis or mysterious conversions of Indian yogis by Sufis.18 The Muslim saints and theologians discussed the question of the extent to which the experiences of the yogis were real, or whether they relied upon a satanic, or at least a magical, basis. They would usually admit the possibility of certain miracles performed by the yogis but would maintain the importance of following the Islamic Path for the performance of true miracles. The sharīʿa is the divine secret, as Gīsūdarāz said, and as late as the eighteenth century the view was expounded that even the greatest ascetic practices and the resulting miracles of a yogi could not properly be compared to even the smallest sign of divine grace manifested in a faithful Muslim.

Another question has to do with the extent to which the ascetic practices of Indo-Muslim saints developed under the influence of Yoga practices. It has been claimed that the strict vegetarianism of some of the Indian Sufis, like Ḥamīduddīn Nagōrī and others, might be attributed to contact with Hindu ascetics. But a story about Rābiʿa al-ʿAdawiyya told by ʿAṭṭār (T 1:64) makes it clear that this saint was credited with complete abstinence from animal products so that the animals no longer fled from her. Similar legends are told of North African saints, and from very early times some ascetics even avoided killing insects—a trend found in the Maghreb as well, where no Hindu or Jain influence can possibly have been present.19

To what extent the breath control advocated by early Sufis in their dhikr developed under the influence of Indian practices cannot be judged properly. It existed, like the “inverted chillah,” among the Sufis of eastern Iran before Sufism spread to India. For the later period, however, we may assume that a deepened interest in the ascetic practices of their Hindu neighbors might have colored some aspects of Indian Sufi life. Some theoretical works about Yoga practices were composed by Indo-Muslim scholars, and a few outstanding Sanskrit works in this field were translated into Persian during the Mogul period.20

On the whole, the boundaries between Muslim and Hindu saints remained quite well defined during the first five centuries of Muslim rule over large parts of India, though there were syncretistic movements, like that of Kabīr in the fifteenth century. The situation changed somewhat with the arrival of the Moguls in India. Babur, from the dynasty of Timur, who established the rule of his house over northwestern India with the decisive Battle of Panipat in 1526, was accustomed to showing reverence to the Sufis in his Central Asian homeland. In his lively and informative Turkish memoirs he tells some interesting stories about the connections between the Timurid princes and some of the mystical leaders of Central Asia. The influence of the Naqshbandiyya on Central Asian politics in the late fifteenth century and after will be discussed later. Babur himself translated into Turkish the Risāla-yi wālidiyya of ʿUbaydullāh Aḥrār, the leading Naqshbandī master of Central Asia (d. 1490), and in one of his poems called himself “the servant of the dervishes.” After his arrival in India, Babur turned his interest to the Chishtī order, which in the following decades became closely connected with the Mogul house.

It was Babur’s grandson Akbar (1556–1605) who, during the half century of his reign, tried to establish a religious eclecticism in which the best elements of all religions known to him would be contained. It seems that his ideas were, to some degree, influenced by the teaching of the Mahdawiyya, the chiliastic movement of Muhammad of Jaunpur, who at the beginning of the sixteenth century had declared himself to be the promised Mahdi.21 Akbar’s two most faithful friends, the court poet Fayżī and the historiographer Abūʾl-Fażl, were the sons of a mystic connected with the Mahdi movement; thus an influence cannot be completely excluded. The ideal of a golden age and restoration of peace all over the world, so typical of chiliastic movements, was in Akbar’s mind, and the “lying together of the lamb and the lion” in the peaceful reign of the Moguls was often represented in Mogul painting of the early seventeenth century.22 Akbar’s religious tolerance was, in its practical consequences, scarcely compatible with Muslim law, and the orthodox became highly suspicious of the dīn-i ilāhī, the Divine Religion invented by the Emperor. Badāūnī’s chronicle reflects the unalloyed hatred of the orthodox theologian who, because of his talents, had been one of the leading translators at Akbar’s court and was forced to translate into Persian “the books of the infidels,” i.e., the Sanskrit epics that were at such variance with the monotheistic ideals of the basically exclusive Muslim mind.

Akbar’s attempts could not bring forth a perfect solution of the problems confronting a large, multireligious country; on the contrary, they evoked much resistance in all segments of the population. Yet they are reflected in the poetry and the fine arts of his time. Persian poetry written at the Mogul court and throughout Muslim India, including Bengal, was dominated by the imagery developed in Iran—most of the leading poets between 1570 and 1650, in fact, came from Iran. Their verses revealed the same mystical feeling as the best poems of their motherland. The constant oscillation between worldly and divine love, the symbolism of roses and nightingales continued; now the vocabulary was enriched by allegorical stories from Indian sources and allusions to the newly discovered European world. But the general tenor of poetry remained by and large the same: endless longing for a beloved who can never be reached, unless the lover undertakes very difficult tasks and gladly offers his life on the thorny path toward the eternal goal. The nostalgia and melancholy so often found in classical Persian poetry was more pronounced in India, hidden under a dazzling exterior, and the later Mogul period once more produced great and truly touching mystical poetry.

It was in the house of a Chishtī saint that Akbar’s heir apparent Salīm, whose throne name was Jihangir, was born. In gratitude for the blessings of this saint, Akbar erected a wonderful Sufi dargāh in his new capital Fathpur Sikri. When Jihangir grew up, he adorned Ajmer, Muʿīnuddīn Chishtī’s city, with beautiful buildings of white marble. The close association of the Chishtiyya with the Moguls, so alien to their previous antigovernment attitude, is reflected in many stories about Akbar and his successors.

The mystical movement aiming at the unification of Hindu and Muslim thought, inaugurated by Akbar, reached its culmination in the days of Dārā Shikōh (1615–59), his great-grandson, the heir apparent of the Mogul Empire.23 This talented prince was the firstborn son of Shāh Jihān and Mumtaz Mahal, whose monumental tomb, the Taj Mahal, symbolizes the ruler’s deep love for the mother of his fourteen children. Dārā became interested in mystical thought very early. It was not the “official” Chishtī order to which he was attracted, but rather the Qādiriyya, represented in Lahore by Miān Mīr, who had come there from Sind, together with his mystically inclined sister Bībī Jamāl. Miān Mīr’s disciple and successor, Mollā Shāh Badakhshī, introduced the prince to the saint. Instead of involving himself actively in politics and military affairs, Dārā indulged in literary activities, to say nothing of his exquisite calligraphy. Widely read in classical works of Sufism, including Rūzbihān Baqlī’s writings, he showed ready ability at compiling biographical studies on the earlier Sufis and collecting their sayings (Ḥasanāt al-ʿārifīn). The Sakīnat al-auliyāʾ is a fine biography of Miān Mīr and the Qādiriyya in Lahore. The admiration with which his collection of biographies of the saints, the Safīnat al-auliyāʾ, was accepted in Indian Sufi circles is evident from the fact that the book was translated into Arabic by Jaʿfar al-ʿAydarūs in Bijapur during the prince’s lifetime. Dārā’s Risāla-yi ḥaqnumā was planned as a completion of Ibn ʿArabī’s Fuṣūṣ, Aḥmad Ghazzālī’s Sawāniḥ, ʿIrāqī’s Lamaʿāt, Jāmī’s Lawāʾiḥ, and other short mystical works, but it lacks the stature of these treatises, just as his mystical poetry, though it shows great skill in the use of words, is somewhat dry. In letters and short treatises Dārā tried to find a common denominator for Islam and Hinduism, and his disputations with a Hindu sage, Bābā Lāl Dās, show his keen interest in the problem of a common mystical language.

Dārā’s great work was the translation of the Upanishads into Persian—a work that he completed with the help of some Indian scholars, but that unmistakably bears the stamp of his personality.24 For him, the Upanishads was the book to which the Koran refers as “a book that is hidden” (Sūra 56:78); thus it is one of the sacred books a Muslim should know, just as he knows the Torah, the Psalms, and the Gospel. Dārā Shikōh’s translation, called Sirr-i akbar, “The Greatest Mystery,” was introduced to Europe by the French scholar Anquetil Duperron, who in 1801 issued its Latin translation under the title Oūpnekʾat, id est secretum tegendum. Neither Dārā Shikōh nor his translator could have foreseen to what extent this first great book on Hindu mysticism would influence the thought of Europe. German idealistic philosophers were inspired by its contents and praised its eternal wisdom in lofty language. Throughout the nineteenth century the Upanishads remained one of the most sacred textbooks for many German and German-influenced thinkers. Its mystical outlook has, to a large extent, helped to form in the West an image of India that has little in common with the realities.

Dārā Shikōh despised the representatives of Muslim orthodoxy. In the same tone as many earlier Persian poets, he could write: “Paradise is there, where there is no mollā.” In the true mystical spirit, he emphasized the immediate experience as contrasted with blind imitation: “The gnostic is like the lion who eats only what he himself has killed, not like the fox who lives on the remnants of other animals’ booty.” The feeling of hama ūst, “everything is He,” permeates all of his work. Dārā practiced his ideas of unity and was surrounded by a number of poets and prose writers who did not fit into the framework of orthodox Islam. There is the very strange figure of Sarmad, a highly intellectual Persian Jew.25 After studying Christian and Islamic theology, he converted to Islam; later, he came as a merchant to India, fell in love with a Hindu boy in Thatta, became a dervish, and eventually joined Dārā’s circle. It is said that he walked around stark naked, defending himself with the lines:

Those with deformity He has covered with dresses,

To the immaculate He gave the robe of nudity.

Sarmad is one of the outstanding masters of the Persian quatrain. Many of his mystical rubāʿyāt are extremely concise and vigorous, revealing the deep melancholy of a great lover. Several of the traditional themes of Persian poetry have found their most poignant expression in his verses. He followed the tradition of Ḥallāj, longing for execution as the final goal of his life:

The sweetheart with the naked sword in hand

approached:

In whatever garb Thou mayst come—I recognize Thee!

This idea goes back at least to ʿAynuʾI-Quḍāt Hamadhānī. Sarmad was, in fact, executed not long after Dārā (1661).

Another member of the circle around the heir apparent was Brahman (d. 1661), his private secretary, a Hindu who wrote good Persian descriptive poetry and prose. There was also Fānī Kashmīrī, the author of mediocre Persian verses to whom a book on comparative religion, the Dabistān-i madhāhib, is, probably wrongly, attributed. (Kashmir, the lovely summer resort of the Moguls, had been a center of mystical poetry since the Kubrāwī leader Sayyid ʿAlī Hamadhānī had settled there, with seven hundred followers, in 1371.)26

Dārā’s attitude was regarded with suspicion by the orthodox, and his younger brother ʿAlamgir Aurangzeb, coveting the crown, took advantage of Shāh Jihān’s illness to imprison his father and persecute his elder brother. After a series of battles, Dārā was eventually betrayed to Aurangzeb, who had him executed in 1659, to become himself the last great ruler of the Mogul Empire (1659–1707). It is worth noting that Dārā’s and Aurangzeb’s eldest sister, Jihānārā, was also an outstanding mystic and a renowned author of mystical works. Her master Mollā Shāh thought her worthy to be his successor, though this did not materialize.

One other member of the Qādiriyya order in Mogul India deserves mention—the great traditionist ʿAbduʾl-Ḥaqq Dihlawī (d. 1642), founder of the traditionist school in Indian Islam. In addition to a great many works devoted to the revival of ḥadīth and to the interpretation of the Koran, to hagiography and Islamic history, he is also credited with mystical treatises. As a member of the Qādiriyya, he commented upon and interpreted famous sayings of the eponym of his order. In a famous letter he expressed his disapproval of some of the claims a leading mystic of his time had made. The mystic in question was Aḥmad Sirhindī, with whose name the “revival of orthodoxy,” or the “Naqshbandī reaction,” is closely connected.

THE “NAQSHBANDĪ REACTION”

It is typical of the situation in Islamic countries, and particularly in the Subcontinent, that the struggle against Akbar’s syncretism and against the representatives of emotional Sufism was carried out by a mystical order: the Naqshbandiyya.27 “The Naqshbandiyya are strange caravan leaders/who bring the caravan through hidden paths into the sanctuary” (N 413). So said Jāmī, one of the outstanding members of this order in its second period. The Naqshbandiyya differed in many respects from most of the medieval mystical fraternities in the central Islamic countries. The man who gave it his name, Bahāʾuddīn Naqshband, belonged to the Central Asian tradition, which traced its lineage back to Yūsuf Hamadhānī (d. 1140). He was “the imām of his time, the one who knew the secrets of the soul, who saw the work” (MT 219).

Hamadhānī’s spiritual affiliation went back to Kharaqānī and Bāyezīd Bisṭāmī; these two saints remained highly venerated in the order. According to the tradition, it was Hamadhānī who encouraged ʿAbduʾl-Qādir Gīlānī to preach in public. Two major traditions stem from him; one is the Yasawiyya in Central Asia, which in turn influenced the Bektashiyye in Anatolia. Hamadhānī’s most successful khalīfa, besides Aḥmad Yasawī, was ʿAbduʾl-Khāliq Ghijduwānī (d. 1220), who propagated the teachings of his master primarily in Transoxania. The way he taught became known as the ṭarīqa-yi Khwājagān, “the way of the Khojas, or teachers.” It is said that he set up the eight principles upon which the later Naqshbandiyya was built:

1) hūsh dar dam, “awareness in breathing,”

2) naẓar bar qadam, “watching over one’s steps,”

3) safar dar waṭan, “internal mystical journey,”

4) khalwat dar anjuman, “solitude in the crowd,”

5) yād kard, “recollection,”

6) bāz gard, ”restraining one’s thoughts,”

7) nigāh dāsht, “to watch one’s thought,” and

8) yād dāsht, “concentration upon God.”

Although Bahāʾuddīn Naqshband (d. 1390) had a formal initiation into the path, he was blessed with an immediate spiritual succession from Ghijduwānī and soon became an active leader of the Khwājagān groups. His main activities were first connected with Bukhara, of which he became the patron saint. Even today, the sellers of wild rue in Afghanistan may offer their merchandise? which is to be burned against the evil eye, with an invocation of Shāh Naqshband.28 His order established connections with the trade guilds and merchants, and his wealth grew parallel to the growth of his spiritual influence, so that he and his followers and friends controlled the Timurid court and carefully watched over religious practices there. At almost the same time the order became highly politicized.

It may be true that as early as the twelfth century a ruler of Kashgar had been a disciple of Ghijduwānī. The Naqshbandīs had taken an active role in the constant internal feuds among the Timurid rulers. But it was not until Khwāja Aḥrār (1404–90) assumed leadership of the order that Central Asia was virtually dominated by the Naqshbandiyya. His relations with the Timurid prince Abū Saʿīd, as well as with the Shibanid Uzbegs, proved decisive for the development of Central Asian politics in the mid-fifteenth century, When Abū Saʿīd settled in Herat, most of the area toward the north and the east was under the influence of Khwāja ʿUbaydullāh Aḥrār, who even had disciples in the country of the Mongols, where Yūnus Khān Moghul, Babur’s maternal uncle, belonged to the order. Their leaders were, and still are, known as Īshān, “they.” It was the Khwāja’s conviction that “to serve the world it is necessary to exercise political power”29 and to bring the rulers under control so that the divine law can be implemented in every part of life.

The Naqshbandiyya is a sober order, eschewing artistic performance—mainly music and samāʿ. Nevertheless, the leading artists at the court of Herat belonged to this order, among them Jāmī (d. 1492), who devoted one of his poetical works to ʿUbaydullāh Aḥrār (Tuḥfat al-aḥrār, “The Gift of the Free”),30 though his lyrical poetry in general reveals little of his close connection with the Naqshbandiyya. His hagiographic work, the Nafaḥāt al-uns, however, is an important account of the fifteenth-century Naqshbandiyya, as well as a summary of classical Sufi thought. The main source for our knowledge of Khwāja Aḥrār’s activities is the Rashaḥāt ʿayn al-ḥayāt, “Tricklings from the Fountain of Life,” composed by ʿAlī ibn Ḥusayn Wāʿiẓ Kāshifī, the son of one of the most artistic prose writers at the Herat court. Jāmī’s friend and colleague, the vizier, poet and Maecenas of artists, Mīr ʿAlī Shīr Nawāʾī (d. 1501), was also an initiate of the Naqshbandiyya. He is the greatest representative of Chagatay Turkish literature, which he encouraged at the court. Thus the order had among its early members two outstanding poets who deeply influenced Persian and Turkish literatures and who, like Nawāʾī, actively participated in political life.31 More than two centuries later members of the “anti-artistic” Naqshbandiyya played a similar role in the Indian Subcontinent.

The center of Naqshbandī education is the silent dhikr, as opposed to the loud dhikr, with musical accompaniment, that attracted the masses to the other orders. The second noteworthy characteristic is ṣuḥbat,32 the intimate conversation between master and disciple conducted on a very high spiritual level (cf. N 387). The close relation between master and disciple reveals itself in tawajjuh, the concentration of the two partners upon each other that results in experiences of spiritual unity, faith healing, and many other phenomena (cf. N 403).

It has been said that the Naqshbandiyya begin their spiritual journey where other orders end it—the “inclusion of the end in the beginning” is an important part of their teaching, though it is an idea that goes back to early Sufi education. It is not the long periods of mortification but the spiritual purification, the education of the heart instead of the training of the lower soul, that are characteristic of the Naqshbandiyya method, “‘Heart’ is the name of the house that I restore?” says Mīr Dard. They were absolutely sure, as many of their members expressed it, that their path, with its strict reliance upon religious duties, Ied to the perfections of prophethood, whereas those who emphasized the supererogatory works and intoxicated experiences could, at best, reach the perfections of sainthood.

The order was extremely successful in Central Asia—successful enough to play a major role in Central Asian politics during the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. In India, the Naqshbandiyya gained a firm footing shortly before 1600, i.e., near the end of Akbar’s reign. At that time, Khwāja Bāqī billāh, a sober but inspiring teacher, attracted a number of disciples who were interested in a law-bound mystical life and opposed the sweeping religious attitude that prevailed in the circles surrounding Akbar.

It was Bāqī billāh’s disciple Aḥmad Farūqī Sirhindī (1564–1624) who was destined to play a major role in Indian religious and, to some extent, political life.33 Aḥmad had studied in Sialkot, one of the centers of Islamic scholarship during the Mogul period. In Agra he came in touch with Fayżī and Abūʾl-Fażl, Akbar’s favorite writers and intimate friends, who were, however, disliked by the orthodox because of their “heretical” views. Aḥmad Sirhindī, like a number of his compatriots, had an aversion to the Shia, to which persuasion some of the southern Indian rulers belonged and which became more fashionable at the Mogul court in the late days of Akbar’s rule and in the reign of Jihangir (1605–27), whose intelligent and politically active wife, Nūr Jihān, was herself Shia. The constant influx of poets from Iran to India during the Mogul period considerably strengthened the Shia element, and it was against them that Aḥmad Sirhindī wrote his first treatise, even before he was formally initiated into the Naqshbandiyya, i.e., before 1600. For a while, he was imprisoned in Gwalior, but he was set free after a year, in 1620. Four years later he died.

Although Aḥmad Sirhindī composed a number of books, his fame rests chiefly upon his 534 letters, of which 70 are addressed to Mogul officials. They were, like many letters by mystical leaders, intended for circulation, with only a few of them meant for his closest friends. He gave utterance to ideas that shocked some of the defenders of orthodoxy, as can be seen from some treatises published against his teachings in the late seventeenth century. The letters have been translated into Arabic, Turkish, and Urdu from the original Persian, and from them Aḥmad gained the honorific titles mujaddid-i alf-i thānī, “the Renovator of the Second Millenium” (after the hijra), and imām-i rabbānī, “the Divinely Inspired Leader.”

In modern times, Aḥmad Sirhindī has usually been depicted as the person who defended Islamic orthodoxy against the heterodoxy of Akbar and his imitators, the leader whose descendants supported Aurangzeb against his mystically inclined brother Dārā Shikōh. Yohanan Friedman has tried to show that this image developed only after 1919, in Abūʾl Kalām Azād’s work, and that it has been eagerly elaborated by many Indo-Muslim, particularly Pakistani, scholars. It may be true that Sirhindī’s direct influence upon Mogul religious life was not as strong as his modern adherents claim, but the fact remains that the Naqshbandiyya, though a mystical order, has always been interested in politics, regarding the education of the ruling classes as absolutely incumbent upon them. We may safely accept the notion that Aḥmad’s successor in the order had a hand in the political development that followed his death and that this situation continued until about 1740.

Aḥmad Sirhindī has been praised primarily as the restorer of the classical theology of waḥdat ash-shuhūd, “unity of vision,” or “testimonial monism,” as opposed to the “degenerate”—as the orthodox would call it—system of waḥdat al-wujūd.34 However, the problem can scarcely be seen in such oversimplified terms. Marijan Molé has interpreted Aḥmad’s theology well (MM 108–10); he explains the tauḥīd-i wujūdī as an expression of ʿilm al-yaqīn, and tauḥīd-i shuhūdī as ʿayn al-yaqīn. That means that the tauḥīd-i wujūdī is the intellectual perception of the Unity of Being, or rather of the nonexistence of anything but God, whereas in tauḥīd-i shuhūdī the mystic experiences the union by the “view of certitude,” not as an ontological unity of man and God. The mystic eventually realizes, by ḥaqq al-yaqīn, that they are different and yet connected in a mysterious way (the Zen Buddhist experiences satori exactly at the same point: at the return from the unitive experience, he realizes the multiplicity in a changed light).

Sirhindī finds himself in full harmony with the great Kubrāwī mystic ʿAlāʾuddaula Simnānī, who had criticized Ibn ʿArabī’s theories. As a good psychologist, he acknowledges the reality of the state of intoxicated love, in which the enraptured mystic sees only the divine unity. But as long as he complies to the words of the divine law, his state should be classified as kufr-i ṭarīqa, “infidelity of the Path,” which may lead him eventually to the sober state in which he becomes aware, once more, of the subjectivity of his experience. Such a reclassification of theories elaborated by the Sufis of old was perhaps necessary in a society in which the mystically oriented poets never ceased singing of the unity of all religions and boasted of their alleged infidelity. This “intoxication” is—and here again classical ideas are developed—the station of the saint, whereas the prophet excels by his sobriety, which permits him to turn back, after the unitive experience, into the world in order to preach God’s word there: prophecy is the way down, is the aspect of reality turned toward creation.

One of Sirhindī’s most astounding theories is, in fact, his prophetology. He spoke about the two individuations of Muhammad, the bodily human one as contrasted to the spiritually angelic one—the two m’s in Muhammad’s name point to them. In the course of the first millennium, the first m disappeared to make room for the alif, the letter of divinity, so that now the manifestation of Aḥmad remains, purely spiritual and unconnected with the worldly needs of his community. In a complicated process, the new millennium has to restore the perfections of prophethood. It is no accident that the change from Muḥammad to Aḥmad coincides with the very name of Aḥmad Sirhindī and points to his discretely hidden role as the “common believer” called to restore these perfections.

That fits well with certain theories about the qayyūm, the highest representative of God and His agent (Aḥmad wrote, in one of his letters: “My hand is a substitute for the hand of God”). It is through the qayyūm that the world is kept in order; he is even higher than the mystical leader, the quṭb, and keeps in motion everything created. Shāh Walīullāh, in the eighteenth century, seems to equate him sometimes with “the breath of the merciful,” sometimes with the “seal of the divine names” or with the universal soul.35 The qayyūm has been elected by God, who bestowed upon him special grace, and, if we believe the Naqshbandiyya sources and especially the Rauḍat al-qayyūmiyya, Aḥmad Sirhindī claimed that this highest rank in the hierarchy of beings was held by him and three of his successors, beginning with his son Muhammad Maʿṣūm.36 The Rauḍat al-qayyūmiyya is certainly not a solid historical work. Written at the time of the breakdown of the Mogul Empire (after 1739), it reflects the admiration of a certain Naqshbandī faction for the master and his family; yet it must certainly rely upon some true statements of Sirhindī and shed light, if not on Naqshbandī history, at least on mystical psychology. The theories about the qayyūmiyya have only begun to be explored by the scholars of Sufism. The role of the four qayyūms in Mogul polities has still to be studied in detail. It is a strange coincidence that the fourth and last qayyīm, Pīr Muhammad Zubayr (Aḥmad’s great-grandson) died in 1740, only a few months after Nadir Shah’s attack on Delhi. The Persian invasion in northwest India had virtually destroyed the Mogul rule,37 and now, the “spiritual guardian,” too, left this world.

Pīr Muhammad Zubayr was the mystical leader of Muhammad Nāṣir ʿAndalīb, the father of Mīr Dard, to whom Urdu poetry owes its earliest and most beautiful mystical verses. Once more, the Naqshbandiyya played a decisive role in the development of a field in which the founders of the order were not at all interested. Members of this order are closely connected with the growth of Urdu literature in the northern part of the Subcontinent.

Urdu, in its early forms, such as Dakhni, had been used first as a literary medium by Gīsūdarāz, the Chishtī saint of Golconda in the early fifteenth century.38 It was developed by mystics in Bijapur and Gujerat in the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. In addition to popular poetry to be remembered by the villagers and the women, several poetical works on mystical theories were composed in this language, which soon became fashionable for profane poetry as well. The first classic to be translated into Dakhni Urdu in the seventeenth century was ʿAynuʾl-Quḍat’s Tamhidāt.

Later, the greatest lyrical poet of the South, Walī, went to Delhi in 1707. It was the year of Aurangzeb’s death—a date that marks the end of the glory of the Moguls. Twilight fell on the political scene. The inherited values were scattered, the social order changed, and even the traditional forms of language and literature were no longer preserved. Walī attached himself to the Naqshbandī master Shāh Saʿdullāh Gulshan, a prolific poet in Persian who was fond of music and was apparently a lovable and soft-hearted person who played a definite role in the poetry- and music-loving society of Delhi. Gulshan was also a friend of Bedil (d. 1721), the lonely poet whose humble tomb in Delhi does not reflect the influence his poetry had upon Afghan and Central Asian, mainly Tajik, literature. Bedil, though not a practicing member of any order, was steeped in the traditions of mystical Islam.39 His numerous math-nawīs deal with philosophical and mystical problems and show a remarkable dynamism along with dark hopelessness. His favorite word is shikast, “broken, break”—an attitude the mystics had always favored for describing their hearts’ state. Bedil’s works of mixed poetry and prose, and his lyrics, offer the reader severe technical difficulties. The vocabulary, the conceits, the whole structure of his thought is unusual, but extremely attractive. His stylistic difficulties are surpassed only by his compatriot Nāṣir ʿAlī Sirhindī (d, 1697), who later became a member of the Naqshbandiyya and considerably influenced the style of some eighteenth-century poets in India without, however, adding anything to the mystical teachings of his masters.

This tradition of highly sophisticated, almost incomprehensible Persian poetry was the breeding ground from which Shāh Saʿdullāh Gulshan came. He quickly discovered the poetical strength of his new disciple Walī. After a few years, it became fashionable in Delhi to use the previously despised vernacular, rekhta or Urdu, for poetry, and in an amazingly short span of time, perfect works of poetry were written in this language, which was now generally used instead of the traditional Persian. The breakdown of the Mogul Empire was accompanied by a breakdown of poetical language. Not only did Urdu grow in the capital, but Sindhi, Panjabi, and Pashto developed literatures of their own during the last decades of Aurangzeb’s reign and continued to flourish during the eighteenth century.

This background must be kept in mind to properly understand the role of the Naqshbandīs in Delhi. Two of the “pillars of Urdu literature” belonged to this order: Maẓhar Jānjānān, the militant adversary of the Shiites, who was killed by a Shia at the age of eighty-one in 1782,40 and Mīr Dard, the lyrical poet of Delhi whose mystical poetry is sweeter than anything written in Urdu. These two men belong as much to the picture of eighteenth-century Delhi as the figure of Shāh Walīullāh (1703–62), the defender of the true faith, initiated into both Qādiriyya and Naqshbandiyya, a scholar and mystic whose works still await serious study in the West. (That he was attacked by a disciple of Maẓhar shows the manifold currents inside eighteenth-century Naqshbandī theology.)41 It was Walīullāh who tried to bridge the gap between the tauḥīd-i shuhūdī and the tauḥīd-i wujūdī, just as he tried to explain the differences between the law schools as historical facts with no basic difference of importance. Shāh Walīullāh also ventured to translate the Koran into Persian so that the Muslims could read and properly understand the Holy Book and live according to its words—an attempt that was continued by his sons in Urdu. He was also instrumental in inviting the Afghan king Ahmad Shah Durrani Abdali to India to defend the Muslims against the Sikh and Mahratta. From Shāh Walīullāh the mystical chain extends to his grandson Shāh Ismāʿīl Shahīd, a prolific writer in Arabic and Urdu, and Sayyid Aḥmad of Bareilly, both known for their brave fight against the Sikh, who had occupied the whole of the Punjab and part of the northwestern frontier.42 The Urdu poet Momin (1801–51), related through marriage with Mir Dard’s family, sided with the two reformers. The political impact of Shāh Walīullāh’s work helped to form the modern Indo-Muslim religious life and attitude toward the British. It has survived in the school of Deoband to our day, though without the strong mystical bias of Shāh Walīullāh’s original thought.

It would be interesting to follow the relations between the great mystical leaders of Delhi during the eighteenth century. Although Shāh Walīullāh was, no doubt, the strongest personality among them, we would prefer to give here some notes about Mīr Dard’s work, since he is an interesting representative of fundamentalist Naqshbandī thought, combined with a deep love of music and poetry. He was a poet of first rank, as well as a pious Muslim, who elaborated some of the Naqshbandī ideas in a quite original way.

KHWĀJA MĪR DARD, A “SINCERE MUHAMMADAN”

...and I was brought out of this exciting stage by special grace and particular protection and peculiar blessing to the station of perfect unveiling and to the Reality of Islam, and was granted special proximity to the plane of the Pure Essence Most Exalted and Holy, and became honored by the honor of the perfection of Prophethood and pure Muhammadanism, and was brought forth from the subjective views of unity, unification and identity toward complete annihilation, and was gratified by the ending of individuality and outward traces, and was exalted to “remaining in God”; and after the ascent I was sent toward the descent, and the door of Divine Law was opened to me ....

Thus wrote Khwāja Mīr Dard of Delhi (1721–85), describing the mystical way that led him from his former state of intoxication and poetic exuberance to the quiet, sober attitude of a “sincere Muhammadan.”43

This spiritual way is not peculiar to Mīr Dard; it reminds us of the traditional Naqshbandī theories. Even Aḥmad Sirhindī had spoken in his letters about his former state of intoxication before he was blessed with the second sobriety, the “remaining in God.” And the “way downward” is, as we saw, connected with the prophetic activities and qualities. Yet in the case of Dard such a statement is worth quoting, since he was usually known as the master of short, moving Urdu poems, as an artist who composed the first mystical poetry in Urdu. Scarcely anyone has studied his numerous Persian prose works, interspersed with verses, in which he unfolds the doctrines of the ṭarīqa Muḥammadiyya, of which he was the first initiate.

Dard was the son of Muhammad Nāṣir ʿAndalīb (1697–1758), a sayyid from Turkish lands and a descendant of Bahāʾuddīn Naqshband. His mother claimed descent from ʿAbduʾl-Qādir Gīlānī. Muhammad Nāṣir gave up the military service to become a dervish; his master was Saʿdullāh Gulshan, “rose garden,” whose role in the development of Urdu poetry has already been mentioned. It was in honor of his master that Muhammad Nāṣir chose ʿAndalīb, “nightingale,” as a pen name, just as Gulshan had selected his nom de plume in honor of his master ʿAbduʾl-Aḥad Gul, “rose,” a member of Aḥmad Sirhiridī’s family. Gulshan spent his later life in Nāṣir ʿAndalīb’s house, where he died in 1728. ʿAndalīb’s second master was Pīr Muḥammad Zubayr, the fourth and last qayyūm from the house of Aḥmad Sirhindī, and it was after Pīr Zubayr’s death that he composed his Nāla-yi ʿAndalīb, “The Lamentation of the Nightingale,” which he dictated to his son Khwāja Mīr, surnamed Dard, “Pain,”44 It is a strange mixture of theological, legal, and philosophical discourses in the framework of an allegorical story, the thread of which is often lost. Now and then, charming anecdotes and verses, dissertations on Indian music or on Yoga philosophy, can be found, and the ending—in which the hero “Nightingale” is recognized as the Prophet himself—is one of moving tenderness and pathetic beauty. Mīr Dard considered this book the highest expression of mystical wisdom, second only to the Koran. It was the source book for teaching the Muhammadan Path.

Muhammad Nāṣir had been blessed about 1734 by a vision of the Prophet’s grandson Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī, who had introduced him to the secret of the true Muhammadan Path (aṭ-ṭarīqa al-Muḥammadiyya). (Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī was considered by the Shādhiliyya to be “the first Pole,” quṭb.)45 Young Dard became his father’s first disciple and spent the rest of his life propagating the doctrine of “sincere Muhammadanism,” which was a fundamentalist interpretation of Islam, deepened by the mystical and ascetic techniques of the Naqshbandiyya. Dard succeeded his father in 1758 and never left Delhi, despite the tribulations that befell the capital during the late eighteenth century. Dard instructed a number of Urdu poets, who would gather in his house for mushāʿiras, and he was a prolific writer in Persian. His greatest work, the voluminous ʿIlm ul-kitāb (1770), gives a detailed account of his religious ideas and of his mystical experiences. It is a kind of spiritual autobiography, which bears an amazing similarity to that of the sixteenth-century Egyptian mystic Shaʿrāanī. Essentially, Dard’s ʿIlm ul-kitāb was conceived as a commentary on the 111 wāridāt, short poems and prose pieces that “descended” upon him about 1750; it then grew into a work of 111 chapters, each headed by the words Ya Nāṣir, “O Helper,” alluding to his father’s name. Whatever he wrote was connected with his father, with whom he had reached perfect identification. Between 1775 and 1785 he composed the Chahār Risāla, four stylistically beautiful spiritual diaries; each of them is divided into 341 sections, corresponding to the numerical value of the word Nāṣir.46

When Dard finished his last book, he had reached the age of sixty-six lunar years, and since his father had died at that age and God had promised him that he would resemble his father in every respect, he was sure that he would die very soon. In fact, he died shortly afterward, on 11 January 1785.

Dard’s close relationship with his father is the strangest aspect of his life. His love for his family meant, at the same time, love for the Prophet, since both parents claimed sayyid lineage and thus special proximity to the Prophet. His father was, for Dard, the mystical guide par excellence. Traditional Sufi theories regard the sheikh as the father of the disciple; for Dard the two functions actually coincided in Muhammad Nāṣir. This led him to interpret the theory of ascent and descent in a peculiar way. He begins, naturally, with the fanā fīʿsh-shaykh, annihilation in the sheikh, which leads to annihilation in the Prophet and annihilation in God; from there, the descent begins. This descent, usually called baqā billāh, was explained by Dard:

fanā in God is directed toward God, and baqā in God is directed toward creation, and one calls the most perfect wayfarer him who comes down more than others, and then again becomes firmly established in the baqā in the Prophet, and he who is on this descendent rank is called higher and more exalted than he who is still in ascent, for the end is the return to the beginning.

But higher than he who has reached this stage is lie who has found baqā in his sheikh, for he has completed the whole circle. This is the terminating rank which God Almighty has kept for the pure Muhammadans whereas the others with all their power cannot be honored by it. (IK 115–16)

This experience was born out of Dard’s relationship with his own father-sheikh and could not be shared by anybody else.

Many of the chapters in the ʿIlm ul-kitāb and the Risālas are devoted to the problems of unity and multiplicity; true “Muhammadan tauḥīd” meant, for him, “immersion in the contemplation of God along with the preservation of the stages of servantship” (IK 609). Dard frequently attacks those “imperfect Sufis” who claim “in their immature minds” to be confessors of unity, but are entangled in a sort of heresy, namely, believing in waḥdat al-wujūd. The vision of the all-embracing divine light—and “Light” is the most appropriate name for God—is the highest goal the mystic can hope for: a vision in which no duality is left and all traces of distinction and self-will are extinguished, but which is not a substantial union. Constant dhikr, fasting, and trust in God can lead man to this noble state. Creation is seen through the image of giving light to pieces of glass—an image known to the earlier mystics: “Just as in the particles of a broken mirror the One form is reflected, thus the beauty of the Real Unity of Existence is reflected in the different apparent ranks of beings. . . . God brings you from the darknesses to the Light, i.e., He brings you who are contingent quiddities from nonexistence into existence” (IK 217). But Dard was well aware that the “pantheistic” formulation so dear to the poets—“everything is He”—was dangerous and incorrect. In common with the elders of his order, he saw that “everything is from Him” and, as the Koran attests, ”whithersoever ye turn, there is the Face of God” (Sūra 2:109). “From every form in this worldly rosebed pluck nothing except the rose of the vision of God.”47 He does not shun the traditional imagery of Persian poetry when he addresses the Lord in his prayer: “We, beguiled by Thy perfect Beauty, do not see in all the horizons anything but Thine open signs . . . . The light of faith is a sign of coquetry from the manifestation of Thy face, and the darkness of infidelity is dressed in black from the shade of Thy tresses.”48

Dard elaborated the theories of the divine as they are reflected in the different levels of creation, a creation that culminates in man, the microscosm reflecting the divine attributes. It is man who is

the seal of the degrees of creation, for after him no species has come into existence, and he is the sealing of the hand of Omnipotence, for God Most Exalted has said: “I created him with My hands” [Sūra 38:75]. He is, so to speak, the divine seal that has been put on the page of contingency, and the Greatest Name of God has become radiant from the signet of his forehead. The alif of his stature points to God’s unity, and the tughrā of his composition, i.e., the absolute comprehensive picture of his eyes, is an h with two eyes, which indicates Divine Ipseity [huwiyya]. His mouth is the door of the treasure of Divine mysteries, which is opened at the time of speaking, and he has got a face that everywhere holds up the mirror of the Face of God, and he has got an eyebrow for which the word “We honored the children of Adam” [Sūra 17:72] is valid. (IK 422)

In fact, as he says in one of his best-known Urdu lines:

Although Adam had not got wings,

yet he has reached a place that was not destined even

for angels.49

It is this high rank of man that enables him to ascend through the stages of the prophets toward the proximity of Muhammad and thus toward the ḥaqīqa Muḥammadiyya, the first principle of individuation.

Like a number of mystics before him, Dard went this way, and his spiritual autobiography (IK 504–5) gives an account of his ascent—in Arabic, as always when he conveys the highest mysteries of faith.

And He made him his closest friend [ṣafī] and His vicegerent on earth by virtue of the Adamic sanctity [see Sūra 3:30].

And God saved him from the ruses of the lower self and from Satan and made him His friend [nājī] by virtue of the Noachian sanctity.

And God softened the heart of the unfeeling before him and sent to him people of melodies by virtue of the sanctity of David.

He made him ruler of the kingdom of his body and his nature, by a manifest power, by virtue of the sanctity of Solomon.

And God made him a friend [khalīl] and extinguished the fire of wrath in his nature so that it became “cool and peaceful” [Sūra 21:69] by virtue of the Abrahamic sanctity.

And God caused the natural passions to die and slaughtered his lower soul and made him free from worldly concern so that he became completely cut off from this world and what is in it, and God honored him with a mighty slaughtering [Sūra 37:107] in front of his mild father, and his father put the knife to his throat in one of the states of being drawn near to God in the beginning of his way, with the intention of slaughtering him for God, and God accepted him well, and thus he is really one who has been slaughtered by God and remained safe in the outward form as his father gave him the glad tidings: “Whoever has not seen a dead person wandering around on earth may look at this son of mine who lives through me and who moves through me!” In this state he gained the sanctity of Ishmael.

God beautified his nature and character and made him loved and accepted by His beloved [Muhammad]. He attracted the hearts to him and cast love for him into his father’s heart—a most intense love!-and he taught him the interpretation of Prophetic traditions by virtue of the sanctity of Joseph [Sūra 12:45].

God talked to him in inspirational words when he called: “Verily, I am God, put off thy shoes! [Sūra 20:12] of the relations with both worlds from the foot of your ascent and throw away from the hand of your knowledge the stick with which you lean on things besides Me, for you are in the Holy Valley” [by virtue of] the sanctity of Moses.

God made him one of His complete words and breathed into him from His own spirit [Sūra 15:29, 38:72], and he became a spirit from him [Sūra 4:169] by virtue of the sanctity of Jesus.

And God honored him with that perfect comprehensiveness which is the end of the perfections by virtue of the sanctity of Muhammad, and he became according to “Follow me, then God will make you loved by His beloved,” and he was veiled in the veil of pure Muhammadanism and annihilated in the Prophet, and no name and trace remained with him, and God manifested upon him His name The Comprising [al-jāmiʿ] and helped him with angelic support.

And he knows through Gabriel’s help without mediation of sciences written in books, and he eats with Michael’s help without outward secondary causes, and he breathes through Israfil’s breath and loosens the parts of his body and collects them every moment, and he sleeps and awakes every day and is drawn toward death every moment by Azrail’s attraction.

God created him as a complete person in respect to reason, lower soul, spirit and body, and as a place of manifestation of all His names and the manifestation of His attributes, and as He made him vicegerent of earth in general for humanity generally, so He also made him the vicegerent of His vicegerent on the carpet of specialisation, especially to complete His bounty in summary and in detail, and He approved for him of Islam outwardly and inwardly [Sūra 5:5], and made him sit on the throne of vicegerency of his father, as heritage and in realisation, and on the seat of the followers of His prophet by attestation and Divine success.

This description shows the steady ascent of Dard until he reaches the closest possible relation to the Prophet through his father.

Many mystics considered themselves to be united with the spirit of a particular prophet, but just as the Muhammadan Reality embraces the spirits of all prophets, Dard realized all their different stages in himself. The name al-jāmiʿ, “the Comprising”, which was given to him, is, in fact, the divine name specialized for man as the last level of emanation, as Ibn ʿArabī claimed.50

Dard’s list is not as comprehensive as the list of twenty-eight prophets shown by Ibn ʿArabī as the loci of particular divine manifestations, nor does it correspond with the list his father mentions: there, Adam manifests the Divine Will or Creativity; Jesus, Life; Abraham, Knowledge; Noah, Power; David, Hearing; Jacob, Seeing; and Muhammad, Existence—the seven basic attributes of God. One may also recall the list developed by the Kubrāwī mystic Simnānī, who connects the seven prophets with the seven laṭāʾ if or spiritual centers of man: the Adam of man’s being, connected with black color, is the qalabiyya, the outward, formal aspect; Noah (blue color), the aspect of the nafs, the lower soul; Abraham (red color), the aspect of the heart; Moses (white color), the aspect of the sirr, the innermost core of the heart; David (yellow color), the spiritual (rūḥī) aspect; Jesus (luminous black), the innermost secret (khafī); and Muhammad (green color), the ḥaqqiyya, the point connected with the divine reality (CL 182). According to these theories, the mystic who had reached the green after passing the luminous black is the “true Muhammadan” (CL 193).

Dard did not propound a color mysticism, but his claims are revealing. He was blessed with auditions, and he records, again in Arabic (for God speaks to His servant in the language of the Koran):

And he said: “Say: If Reality were more than that which was unveiled to me, then God would verily have unveiled it to me, for He Most High has completed for me my religion and perfected for me His favor and approved for me Islam as religion, and if the veil were to be opened I would not gain more certitude—verily my Lord possesses mighty bounty.” (IK 61)

After this report of an experience in which Dard was invested a the true successor of the Prophet, he goes on to speak of the names by which God has distinguished him. He gives a long list of his “attributive and relative” names: ninety-nine names have been bestowed upon him, corresponding to the ninety-nine most beautiful names of God. We cannot judge whether these names point to a veiling of his real personality or whether they are an expression of the search for identity reflected in his poetry and prose. It may be remembered that his father was predisposed to surrounding the heroes of his books with long chains of high-sounding names.

Only a few people probably knew these secret names of Dard or the comprehensive theological system hidden behind the short verses he wrote, which became the favorite poetry of the people of Delhi,

Delhi which time has now devastated—

Tears are flowing now instead of its rivers:

This town has been like the face of the lovely,

and its suburbs like the down of the beloved ones!51

He prayed for the unhappy population that God might not allow foreign armies to enter the town—as happened time and again during his lifetime. He was certainly being idealistic when he expressed the thought that it would be better for the poverty-stricken and destitute inhabitants of the capital “to follow the path of God and the Muhammadan Path, so that they may pluck the roses of inner blessings from the rose garden of their company and listen to the ‘Lamentation of the Nightingale, and understand his works.”52