Redstone 15" × 22"

Redstone 15" × 22"

From a geologist's point of view, rocks are a wide-open subject—as many-colored as the rainbow, as richly textured as the sea. There are smooth rocks and rough rocks, rocks born in the liquid cauldron of a volcano or laid down over eons at the bottom of some prehistoric inland ocean. There are rocks sculpted by the wind or rounded by the patient action of water. There are rocks as pocked and punctuated as a sponge and rocks striated with delicate lines as fine as a feather's barbs. There are, in other words, as many forms and textures for the artist to explore as there are for the dedicated geologist—and as you can tell, this is one of my favorite subjects.

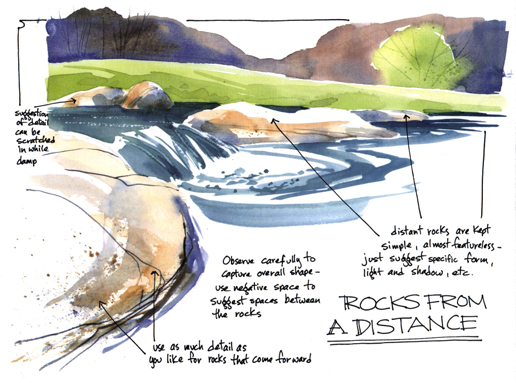

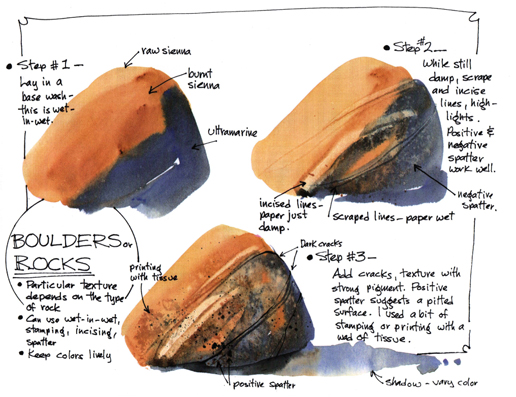

Capturing the varied forms of rocks, whether they are as faceted as a crystal or as voluptuously curved as a shoulder, is a constant challenge. It's necessary to pay attention not only to overall form but to the effects of light and shadow and how they help describe texture. But it's not as difficult as it sounds. Again, a logical approach can make even the most complex rock form easy to capture on paper: Look for the backbone of form first, then worry about detail.

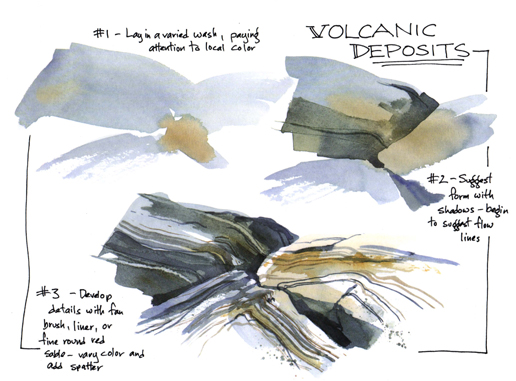

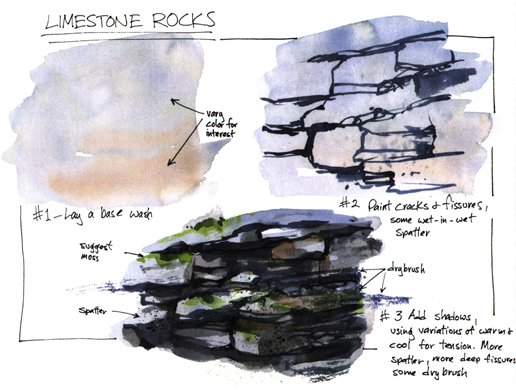

Use color to give a sense of place—Nevada's redstone formations are very different from the pale, lichen-and-moss-painted limestone of northern Missouri, where I live. The Payne's gray rocks of coastal Maine—remnants of ancient volcanoes—and the pinkish glacial erratics of the upper Midwest are a pleasure to paint. Texture comes into play when colors are similar. The rugged, iron-stained limestone of the Missouri Ozarks is very different from the slick rocks of the Southwest's canyon lands, though both share a reddish hue.

And of course, we use rocks as a resource. Here, we've suggested several ways to depict the rock walls of an old building using the same principles, and thrown in a bit of brickwork while we're at it—these man-made “stones” may be more uniform than nature's rocks, but they can still challenge the artist.