Molly in Mufti 11" × 15"

Collection of Molly Hammer

Molly in Mufti 11" × 15"

Collection of Molly Hammer

Think of the varieties of textures within this single topic—a baby's cheek is very different from that of a sailor accustomed to long hours on the ocean under an unrelenting sky. A face with a fine, woven net of lines has a texture quite removed from that belonging to a fresh young girl.

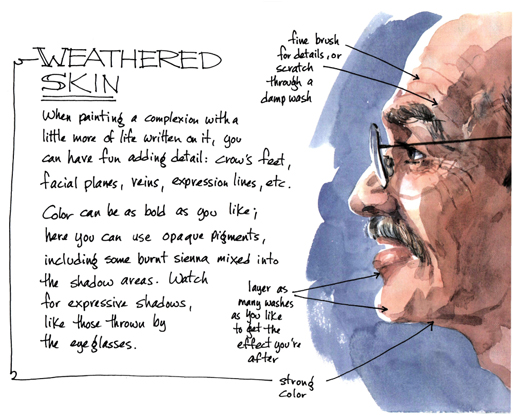

The technique you choose can go a long way toward exploring these differences. Wet-in-wet can be used to suggest soft, delicate skin, while drybrush can add all the texture you'd ever need. A combination of these techniques can cover literally any situation, allowing you to lay in a soft undertone of color, then build up layers of character on top. Even the pigments you choose can add to the illusion of texture. Transparent pigments like alizarin crimson can really express a glow, while the graininess inherent in some of the opaque, separating pigments like burnt umber or burnt sienna (cooled with ultramarine or manganese) contributes a texture of its own.

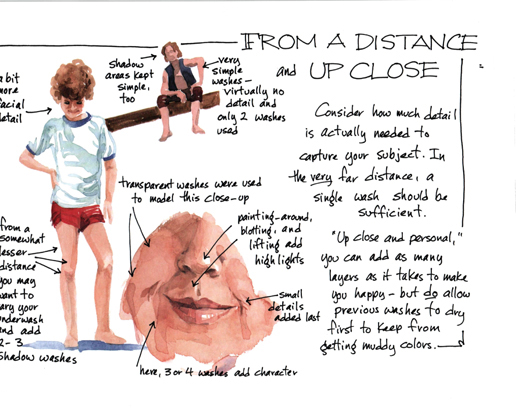

When working with young skin, keep your washes relatively simple. Lay them in quickly and decisively, then get out. Don't keep working over the area or it will become muddied—and may develop rough textures where you want smooth ones. When you're working with a subject with a bit more character, however, you can add as many washes as you like, although it's usually more satisfactory to allow each to dry thoroughly before adding subsequent layers. Reserve the bolder colors for these older, more highly textured subjects, and watch for areas that add character—smile lines, crow's-feet, and so on.

And of course, the distance between you and your subject will again affect how much texture you want; distant subjects require almost none, while those close up can take as many layers as you like.