This chapter will set out the ways in which Hollywood has been conceptualised, and the endeavours to map the postmodern within these accounts. It offers a meta-critical analysis of the key concepts governing the theorisation of the development of Hollywood cinema, focusing on the classical, its relation to the modern, the post-classical and the postmodern. This involves looking at historical models of studio-era Hollywood, the Hollywood Renaissance and New Hollywood. My analysis is primarily conceptual – I am interested in the elements that fall outside the frame provided by the classical as well as the theoretical divisions that are kept in play by the characterisation of the different epochs in Hollywood’s history.

Within the limited take up of postmodern theory in Film Studies, the dominant trend is to map the postmodern onto existing paradigms and it is usually equated with aspects of the post-classical and new Hollywood. However, what I want to demonstrate across the course of this chapter is that taking up postmodern modes of theorising involves rethinking the nature of particular paradigms – specifically the limits of the classical – and indeed the whole project of historically periodising aesthetic styles. The final section of this chapter will take up Jean-François Lyotard’s conception of the temporality of the postmodern in order to escape unconvincing linear models of development or decline, as well as setting up a model of multiple aesthetic forms, including the postmodern.

David Bordwell, Janet Staiger and Kristin Thompson aimed to construct a new theoretical paradigm for analysing Hollywood that would forge strong links between its aesthetic, industrial and economic aspects. Their aim is made clear in the preface to The Classical Hollywood Cinema: ‘to see Hollywood film making from 1917–60 as a unified mode of film practice is to argue for a coherent system whereby the aesthetic norms and the mode of film production reinforced one another’ (Bordwell et al. 1985: xiv; emphasis added). Thus two things are instantly striking about the classical paradigm: its breadth of scope (textual to industrial) and its presentation as a single system. While the dates 1917–60 suggest the new paradigm is historical, the drive to singularity and universality indicate its basis within analytic philosophy: ‘the idea of a “classical Hollywood cinema” is ultimately a theoretical construct and as such it must be judged by criteria of logical rigour and instrumental value’ (1985: xv; emphasis added).

Bordwell’s account of the classical utilises traditional aesthetic definitions of the key features of classicism: ‘elegance, unity [and] rule-governed craftsmanship’ (1985: 4). The rules that govern Hollywood cinema are said to be derived from its own discourses, including trade journals, publicity material and screenwriting manuals. Bordwell consistently privileges narrative: ‘telling a story is the basic formal concern’ and stresses the unified nature of the film text: ‘unity is a basic attribute of film form’ (1985: 3). Hollywood films are said to be ‘“realistic” in both an Aristotelian sense (truth to the probable) and a naturalistic one (truth to historical fact)’ (ibid.). The impression of realism is compounded by editing techniques: ‘the Hollywood film strives to conceal its artifice through techniques of continuity and “invisible” storytelling’ (ibid.).

While the classical paradigm does not address the issue of audience reception (see Bordwell

et al. 1985: xiv), the audience is crucial to the formulation of two further rules. The film ‘should be comprehensible and unambiguous; and [possess] a fundamental emotional appeal that transcends class and nation’ (Bordwell 1985: 3). The universal model of spectatorship set out here requires that mainstream cinema be legible to everyone in the same way. Bordwell argues that this is possible because any viewer follows the protocols of reading derived from ‘the system of norms operating in the classical style’ (1985: 8). Thus the overriding principle of narrative causality in the classical is translated by ‘the viewer … into a tacit strategy for spotting the work’s unifying features … sorting the film’s stimuli into the most comprehensive pattern’ (ibid.). Borrowing terms from Ernst Gombrich, Bordwell argues that the classical film utilises well-known schemata, such as Hollywood film editing, which ‘constitute the basis of the viewer’s expectations or mental set’ (1985: 8). Thus the film’s schemata ‘elicit particular activities from the viewer’, the viewer deciphering the film by trying out and selecting the appropriate elements of their mental set (ibid.).

Bordwell argues that classical narrative takes the form of logical chains of cause and effect that are predominantly character-centred. ‘Here … is the premise of Hollywood story construction: causality, consequence, psychological motivations, the drive toward overcoming obstacles and achieving goals’ (1985: 13). Having made ‘personal character traits and goals the causes of action’ and thus the underlying structure of the narrative (1985: 16), Bordwell is obliged to conceptualise characterisation as fundamentally consistent: ‘a character is made a consistent bundle of a few salient traits, which usually depend upon the character’s narrative function’ (1985: 14). The classical film is said to have two main lines of action: the first is usually heterosexual romance – winning the love of a man or woman is a key goal of many classical protagonists – while the second can take many forms: ‘business, spying, sports, politics, crime, show business – any activity … which can provide a goal for the character’ (1985: 16). Importantly, the ‘tight binding of the second line of action to the love interest is one of the most unusual qualities of the classical cinema’ (1985: 17), giving these films their distinctive unity.

The unity of the classical film text is sustained by Bordwell’s analysis of openings and endings. He argues that the classical film offers an opening exposition of events that is ‘concentrated and preliminary’ (1985: 28). The opening introduces the main protagonists, sets up character goals and often provides key motifs that are utilised across the film. The audience is immediately immersed within the action, the film beginning in

media res, and thus the ‘exposition plunges us into an already-moving flow of cause and effect’ (ibid.). Bordwell notes that all the one hundred films in the primary sample had a clearly demarcated ending in the form of an epilogue defined as ‘a part of the final scene, or even a complete final scene, that shows the return of a stable narrative state’ (1985: 36). Endings frequently rhyme with the opening exposition as well as utilising key motifs and/or running gags from across the film. Importantly, classical narration is said to end only once all the gaps in the narrative have been filled, creating a tightly unified text (1985: 39).

The classical Hollywood film is typically said to show narrative events in temporal order. The exception to this is the complex use of flashbacks from the late 1930s to the 1950s (1985: 41–2). The compression of the story events into the screen time is achieved partly through the use of ellipsis and montage sequences. The ‘forward flow of the story action’ (1985: 45) is secured by deadlines and appointments, which also integrate with character goals thereby consolidating the cause and effect logic of the narrative. Bordwell comments that ‘as a formal principle, the deadline is one of the most characteristic marks of Hollywood dramaturgy’ (1985: 46). Another formal principle is the repetition of story information; indeed, he suggests that ‘the Hollywood slogan is to state every fact three times’ (1985: 31).

Classical Hollywood cinema is said to subordinate space to the construction of narrative. Classical editing techniques are characterised by invisibility, providing a transparent ‘plate-glass window’ (Bordwell 1985: 50, 59) onto another world. Importantly, Bordwell’s construction of classical Hollywood as a series of rule-governed processes is sustained by editing: ‘of all Hollywood stylistic practices, continuity editing has been considered a set of firm rules’ (1985: 57). Adherence to the 180-degree rule underpins a number of key devices including: shot/reverse-shot patterns, point-of-view editing, eyeline matches and matches on action (1985: 56–8). Moreover such devices act as ‘traditional schemata which the classical filmmaker can impose on any subject’ (1985: 57) thereby ensuring that the spectator is carefully cued to fill in any gaps. Thus the transparency of the diegetic world is achieved partly through its rule-governed presentation and partly through ‘the viewer, [who] having learned distinct perceptual and cognitive activities, meets the film halfway and completes the illusion of seeing an integral fictional space’ (1985: 59; emphasis added).

Bordwell’s vision of the classical can thus be seen to present the Hollywood film text as a tightly unified whole. In addition, his model of a rule-governed stylistic system has a profound impact on Janet Staiger’s conceptualisation of Hollywood’s production practices. She takes up a circular position, arguing that Hollywood’s modes of production are both ‘the historical conditions allowing a group style to exist [and] the effect of the group style’ (Bordwell

et al. 1985: 88). She traces the ways in which the institutional discourse – created by advertising, trade papers, professional and labour associations – served to standardise the Hollywood group style and production practices across the industry (1985: 96–108). ‘This institutional discourse explains why the production practices of Hollywood have been uniform through the years and provides a background for a group style which [is] also stable through the same period’ (1985: 108). Thus the rule-governed stability of the classical model actually acts as both effect and cause: it is the end product of an equally stable production process, and a template for industrial standardisation, uniformity and stability.

Hollywood’s production processes are frequently conceptualised as the epitome of capitalist mass production and paralleled with Henry Ford’s mass production of automobiles (Bordwell et al. 1985: 90). The Fordist-Taylorist assembly-line model of factory production involves a ‘detailed division of labour. Here the process of making a product is broken down into discreet segments and each worker is assigned to repeat a constituent element of that process’ (1985: 91). Each worker’s repetition of one element of the process maximises efficiency, while also ensuring that they have no relation to the end product as a whole. By contrast, Staiger argues that Hollywood’s production processes were closer to serial manufacturing ‘with craftsmen collectively and serially producing a commodity’, an end product to which they all had a relation (1985: 93, 336). She notes that Hollywood’s drive towards product differentiation, stressing novelty and innovation in order to lure audiences to the cinema again and again, constitutes a further departure from the Fordist-Taylorist model of the perfect replication of the same product (1985: 109–11).

Staiger’s analysis of the institutional discourse of advertising foregrounds the importance of stars, genre and spectacle in the development of Hollywood cinema (Bordwell

et al. 1985: 95–101). While she follows Bordwell, ultimately subordinating these elements to narrative, their potential to unsettle the paradigm of the classical is suggested at various points across the book. All three elements emerge in Bordwell’s analysis of narrative motivation, defined as ‘the process by which a narrative justifies its story material and the plot’s presentation of that story material’ (1985: 19). Motivation is said to take four main forms: compositional, realistic, intertextual and artistic. The example of compositional motivation involves cause and effect: ‘a story involving a theft requires a cause for the theft and an object to be stolen’ (ibid.). This is presented as the dominant form of narrative motivation, which serves to secure textual coherence. Realistic motivation is based on the principle of verisimilitude. Thus a historical drama will require costumes, props and settings that evoke the period in which the narrative is set.

The third form – intertextual motivation – has the potential to break down Bordwell’s model of the hermetically sealed film text because it covers features that are derived from previous texts, such as star persona and generic conventions. Bordwell notes that an audience would expect a film starring Marlene Dietrich to feature her singing a cabaret song at some point. His comment that her number could be ‘more or less causally motivated’ indicates that the song might challenge the precedence of compositional motivation, temporarily suspending the strict narrative logic of cause and effect (1985: 20). The example is also indicative of a set of viewer expectations established through an aggregate of previous texts rather than the application of particular schemata. Thus informed viewers would not just expect Dietrich to sing but would piece together aspects of her performance, costume and filmic presentation to form a much more complex set of expectations. Distinctive features of Dietrich’s star persona, including key elements of androgyny and bisexuality, are actually established via musical numbers, for example her famous appearance in black tie for the ‘Quand l’Amour Meurt’ number in Morocco (Josef von Sternberg, 1930).

The fourth and final type of narrative motivation that Bordwell delineates is artistic motivation in which specific features draw attention to the film’s status as a film. He acknowledges that the process of ‘calling attention to a work’s own artfulness’ (1985: 21) appears to challenge his conception of classical cinema as typically transparent and self-effacing. Artistic motivation encompasses all modes of visual spectacle, including displays of ‘flagrant technical virtuosity’ (ibid.) from lighting design to complex camera movements. It also applies to brief, self-reflexive moments, such as overt references to other films and stars, which draw attention to the film’s artifice. For example

My Favorite Brunette (Elliott Nugent, 1947) in which ‘Ronnie Johnson tells Sam McCloud he wants to be a tough detective like Alan Ladd; McCloud is played by Alan Ladd’ (ibid.). Bordwell acknowledges that an appreciation of visual virtuosity and aural in-jokes requires a sophisticated viewer: ‘To some extent artistic motivation develops connoisseurship in the classical spectator’ (1985: 22).

A film may also use artistic motivation ‘to call attention to its own particular principles of construction’ (ibid.). Bordwell gives the example of the ‘You Were Meant For Me’ number from Singin’ in the Rain (Gene Kelly & Stanley Donen, 1952). Don Lockwood (Gene Kelly) carefully places the machinery required to create the right atmosphere for a romantic musical number – coloured lights, mist and a soft summer breeze – before he begins singing to Kathy Selden (Debbie Reynolds), thereby drawing attention to the conventions for staging such numbers. This process of ‘baring the device’ is said to be common in comedies and musicals, the latter often having narratives which centre on putting on a show (ibid.). While acknowledging the importance of artistic motivation in two major genres, Bordwell asserts that classical cinema ‘does not bare its devices repeatedly and systematically’ (1985: 23), unlike avant-garde works such as Michael Snow’s La Région Centrale (1971). As a result, the classical is said to subordinate artistic motivation to compositional motivation.

It is important to note that Bordwell positions the avant-garde method of baring the device as exemplary of pure artistic motivation, setting up the contrast with the classical, which then appears unsustained and inconsistent. In this way reflexivity and the foregrounding of filmic conventions within the classical are positioned as brief, ornamental moments while the fundamental level of meaning is located within the narrative. The privileging of narrative motivation serves to contain the other forms, thereby subordinating a diversity of different aesthetic strategies, specifically intertextuality and reflexivity, in order to maintain the unity of the classical text.

Modernity/Modernism

Miriam Bratu Hansen argues that definitions of the classical within film theory utilise and reinforce long-standing oppositions between classicism and modernism from aesthetics and philosophy (2000: 335–6). E. Ann Kaplan notes the take up of the same oppositions to conceptualise mass culture in her analysis of MTV as a postmodern art form: ‘the aesthetic discourse dominant in Western culture from the late nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century has polarized the popular/realist commercial text and the “high art” modernist one’ (1987: 40). She unpacks the binary oppositions delineating the defining characteristics of classical and modernist/avant-garde texts in a useful table, suggestively entitled ‘Polarized filmic categories in recent film theory’ (1987: 41). Both theorists draw attention to the ways in which the classical film tends to accrue increasingly negative characteristics when conceptualised as the opposite of the modernist text.

Table 1 Polarized filmic categories in recent film theory

| The classical text (Hollywood) |

The avant-garde [modernist] text |

| Realism/narrative |

Non-realist anti-narrative |

| History |

Discourse |

| Complicit ideology |

Rupture of dominant ideology |

Kaplan runs together the classical text’s qualities of realism, narrative and history on the grounds that all three combine to achieve the ‘effacement of the means of production’, covering over the labour of directing and acting as well as technological processes of filming and editing (1987: 40). The Hollywood film creates a ‘realistic’ diegetic world by offering a narrative that appears to unfold transparently by itself: ‘the “story told from nowhere, told by nobody”’ (ibid.). This transparency is maintained by the techniques of continuity editing, which are also said to rigidly position the spectator within the narrative flow (ibid.). Moreover, the opposition History/Discourse, here basically synonymous with self-effacing/self-reflexive, simply erases the categories of narrative motivation that Bordwell was prepared to contemplate, presenting the classical as incapable of baring the device or offering self-reflexive commentary.

Crucially, the absence of such interrogative and self-reflexive techniques means that classical texts are seen simply to embody dominant ideology. Bordwell briefly touches on this aspect, noting that the figure of the goal-orientated protagonist is ‘a reflection of an ideology of American individualism and enterprise’ (1985: 16). However, Kaplan’s final tabular opposition draws on older critiques of mass culture, beginning with Theodor Adorno, in which studio-era Hollywood is seen to be absolutely complicit with the values of capitalism. By contrast, the self-reflexive modernist text can offer a ‘self-conscious play with dominant forms’ that may include ‘a critique of mainstream culture’, thereby rupturing and subverting dominant ideology (1987: 40–1). The binary of ideological versus progressive plays a crucial role in theories of counter cinema, offered by Peter Wollen, Stephen Heath and Laura Mulvey among others, which have been dubbed ‘political modernism’ (see Hansen 2000: 337–8). Kaplan’s table nicely encapsulates the ways in which aesthetic strategies become synonymous with stark political stances. In three stages the distinction between the classical and the modernist is transformed into an absolute division between ideological complicity and subversion.

Hansen argues that the positioning of Hollywood within the binary of the classical versus the modernist is enormously problematic for two reasons. Firstly, it covers over Hollywood’s relation to ‘mid-twentieth-century modernity, roughly from the 1920s through the 1950s – the modernity of mass production, mass consumption and mass annihilation’ (2000: 332). Secondly, the application of ‘stylistic principles modelled on seventeenth-century and eighteenth-century neo-classicism … to a cultural formation that was … perceived as the incarnation of the modern’ (2000: 337) is fundamentally anachronistic. Thus the take up of the terminology of the classical ultimately serves to hide Hollywood’s relation to a specific historical and cultural context – modernity as experienced in the United States of America.

Hansen suggests that these problems are largely caused by the concept of the classical itself, which ‘implies the transcendence of mere historicity’, setting up ‘a transhistorical [sic] ideal, a timeless sense of beauty, proportion, harmony and balance derived from nature’ (2000: 338). The shift away from the specificities of cultural context is most obvious in Bordwell’s universal model of spectatorship. Narrative and stylistic schemata lead to the development of spectatorial mental sets thereby ensuring that all spectators go about deciphering classical texts in the same way. By contrast, Hansen argues in favour of recognising the culturally diverse nature of Hollywood’s global audience. ‘If classical Hollywood cinema succeeded as an international … idiom … it did so not because of its presumably universal narrative form but because it meant different things to different people and publics, both at home and abroad’ (2000: 341). She notes that key contextual factors such as: programming, censorship, marketing and subtitling, would make for markedly different conditions of reception within different countries, thereby sustaining multiple, culturally diverse readings of the film texts.

Hansen argues that the solution to the problems of the classical model is the repositioning of Hollywood within its historical relation to modernity. She presents Hollywood cinema from the 1920s to the 1950s as ‘an aesthetic medium up-to-date with Fordist-Taylorist methods of industrial production and mass consumption, with drastic changes in social, sexual and gender relations, in the material fabric of everyday life’ (2000: 337). Thus Hollywood cinema is modern in both its modes of production and consumption as well as having the capacity to reflect on the conditions of modernity. Hansen argues in favour of reconceptualising Hollywood cinema as ‘a cultural practice … as an industrially produced, mass based,

vernacular modernism’ (ibid.; emphasis added). In this way, she sets up a distinction between two different modes of reflecting on modernity: modernist works of art and the popular cultural forms of vernacular modernism.

Hansen argues that the cultural forms of vernacular modernism were capable of articulating and embodying many different relations to modernity. Hollywood cinema constituted ‘a cultural horizon in which the traumatic effects of modernity were reflected, rejected or disavowed, transmuted or negotiated’ (2000: 231–2). Importantly, she suggests that this constitutes a mode of reflexivity that should be distinguished from modernist ‘formalist self-reflexivity’. The latter involves the foregrounding of technique for specific effects, typically the distancing of the spectator from the work of art in order to facilitate their developing critical awareness of the work and, indeed, capitalist society and ideology in general. Hollywood cinema is reflexive in that it offers a collective perspective on modernity, thereby acting as ‘an aesthetic horizon for the experience of industrial mass society’ (2000: 342). Following Siegfried Kracauer, Hansen argues that slapstick films offer this type of reflexive engagement with Fordist-Taylorist industrialisation. Films such as Modern Times (Charles Chaplin, 1936) are said to both articulate and disrupt ‘the violence of technological regimes, mechanization and clock time’ (2000: 343). Her focus on slapstick suggests that a more substantive engagement with the genre of comedy could generate awareness of a multiplicity of reflexive textual practices. Crucially, she challenges modernist definitions, where reflexivity is narrowly aligned with specific forms of social and political critique.

Hansen makes clear that her compelling vision of an ambivalent modernity arises from her position within contemporary postmodern culture; however, she does not address the nature of the transition from modernity to postmodernity (2000: 344). Moreover, her concept of vernacular modernism overlaps with the postmodern on two key issues: the status of mass culture and the delineation of reflexive aesthetic strategies. Finally, Hansen’s model draws together the epoch of modernity and the aesthetic strategies of vernacular modernism, presenting a model in which the economic, cultural and aesthetic are all intimately inter-related. This chapter will demonstrate that an effective mapping of postmodern aesthetic strategies requires a fundamental reconsideration of the inter-relations between these diverse aspects.

After the Classical

Determining the end-date of the classical is not at all straightforward. While Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson’s original study goes up to 1960, two of the authors have been vehement in their denial of the existence of the post-classical, arguing that contemporary Hollywood demonstrates the longevity of the classical paradigm (see Thompson 1999; Bordwell 2006). Other theorists argue that important changes to economic and industrial conditions in post-war Hollywood serve to usher in an era that has been variously entitled modern, new or post-classical. The key historical changes, such as the end of vertical integration and the demise of censorship, will be outlined here.

The era after the classical also comprises two very differently characterised periods: the ‘Hollywood Renaissance’, beginning with

Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967) and ending in the mid- to late-1970s; and ‘New Hollywood’, which is synonymous with the rise of the blockbuster, beginning with the advent of

Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975) to the present day. While the precise dates of each historical period are subject to debate, matters are further complicated by a lack of critical consensus concerning terminology. Geoff King notes that some critics use the term ‘New Hollywood’ for the entire era post-World War II to the present day, others apply it specifically to the decade of the Hollywood Renaissance, while a number use it purely with reference to a cinema dominated by the blockbuster (2002b: 3). This account will treat the Hollywood Renaissance and New Hollywood as two distinct periods, following the historical divisions given at the beginning of the paragraph, in order to set out the characteristic aesthetic features of each period and to trace the ways in which each reprises and reworks key binaries, specifically modernism/classicism, classical/post-classical and modernist/postmodern.

Historians charting the many economic and industrial changes to Hollywood typically assign a key role to the Paramount case of May 1948 in which the Supreme Court ruled that the studio system constituted an illegal monopoly (see King 2002b: 27–9; Krämer 2005: 20). By the 1930s the ‘big five’ studios – Warner Bros., Loew’s Inc., Paramount, Twentieth Century Fox and RKO – all had fully vertically integrated operations, which meant they controlled the production, distribution and exhibition of their films. Tino Balio demonstrates that such dominance resulted in a series of unfair practices, including: ‘[block] booking, the fixing of admission prices, unfair runs … discriminatory pricing and purchasing arrangements favoring affiliated theater circuits’ (1985: 402). While the big five did not directly control the majority of cinemas country-wide, they owned the majority of the ‘movie palaces’, major first-run cinemas in big cities, which comprised 70 per cent of the box-office takings for the home market (see King 2002b: 26). The successful prosecution of the big five under antitrust laws against monopoly practices had a number of significant effects.

The mandatory selling off of movie theatres made places of exhibition more independent. They no longer had to purchase blocks of films from one specific studio and no deals could be done between the big five to secure exhibition. Balio notes that the numbers of art-house cinemas across America increased from fewer than a hundred in 1950 to over six hundred by the mid-1960s (1985: 405). These independent cinemas acted as screening outlets for a diversity of products including reissues of Hollywood ‘classics’, European films and independently-made American films. The studios’ loss of their sites of exhibition had a profound effect on film censorship in that it made it impossible to secure the implementation of the Production Code. The Production Code Administration had been set up in 1934, reviewing scripts and previewing completed prints to ensure they met the guidelines of the code. All films had to gain a seal of approval from the PCA before they could be distributed and exhibited (see King 2002b: 29–34). However, the rise of independent art-house cinemas meant films that did not gain a seal could now find sites of exhibition (see King 2002b: 30). Eventually, this inability to enforce the Code led to its replacement with a ratings system in 1968 (see Krämer 2005: 47–9).

The timing of the Paramount decrees was unfortunate for the studios, because it coincided with a very significant decline in audience numbers. Krämer notes that ‘average weekly attendance … plummeted from 82 [million] in 1946 to 73 [million] in 1947’ with a further 10 per cent drop each year, falling to 42 million by 1952 (2005: 20). A variety of reasons are given for the decline in numbers: the post-war baby boom, new modes of urban planning that increased suburbanisation and the rise of alternative leisure pursuits, particularly the advent of television during the 1950s (see Balio 1985: 401–2; Bordwell

et al. 1985: 332; Krämer 2005: 20–1). Importantly, the significant decline of income coupled with the loss of secure sites of exhibition meant that the studios’ distinctive ‘factory-style system’ with ‘huge permanent staffs and in-house departments’ (King 2002b: 27–8) was now prohibitively expensive.

Historians agree that the period of the late-1940s to the mid-1950s saw the end of the factory-style studio and a rise in independent production (see Balio 1985: 404–5; King 2002b: 28). Janet Staiger charts this shift as a move away from a ‘producer unit’ system of production in which ‘a group of men supervised six to eight films per year … each producer concentrating on a particular type of film’, to a ‘package unit’ system (Bordwell et al. 1985: 320). In the first mode of production, the labour and materials to make a film were offered by a single company: the studio. While in the second, ‘a producer organized a film project: he or she secured financing and combined the necessary laborers … and the means of production’ (1985: 330). She notes that agencies could play the role of producer in the package unit system, charting the rising importance of the William Morris Agency and the Music Corporation of America (MCA) (1985: 333). Staiger contends that the shift from the producer unit system to the package unit system did not substantially affect the stability or uniformity of the classical Hollywood production mode (Bordwell et al. 1985: 334–5). However, others see the shift as a substantial change (see Schatz 1993; MacDonald 2000; Hall 2002; King 2002b).

The Hollywood Renaissance

Goeff King argues that while key changes to the exhibition, consumption and production of Hollywood films post-1948 ‘helped to create space for the Hollywood Renaissance’, the deciding factor was the financial crisis experienced by the studios in the mid-to-late 1960s (2002b: 34). Hollywood had two conflicting strategies for dealing with the decline in audience numbers: the targeting of films to specialised, typically adult, audiences, and the creation of lavish roadshow productions that appealed to the broad, family audience (2002b: 34–5). Peter Krämer notes that from 1960 to 1966, ‘between one and four of the top five films every year were epics or musicals with roadshow releases’ (2005: 40). These big-budget films were lavish productions that required a substantial initial investment, which would then be recuperated during the period of their theatrical run. The crisis came about when the majors ‘poured money into a series of musical extravaganzas’, such as

Doctor Dolittle (Richard Fleischer, 1967) and

Star! (Robert Wise, 1968), which failed at the domestic box office (see King 2002b: 35). At the same time, lower-budget, contemporary productions, such as

Bonnie and Clyde and

The Graduate (Mike Nichols, 1967) proved commercially successful, thereby encouraging a trend. The latter cost three million dollars to make and grossed US$105 million at the American and Canadian box offices, coming first in Krämer’s table of the ten highest grossing hits of 1967 (2005: 106–7).

Krämer argues that Bonnie and Clyde plays a key role in popular and critical conceptions of a new cinema emerging in the mid-to-late 1960s: the Hollywood Renaissance. On 8 December 1967 the cover of Time magazine featured a publicity still from the film alongside the caption ‘“The New Cinema: Violence … Sex … Art”’; the article inside the magazine celebrated the film for beginning ‘a new style, a new trend’, utilising elements of stylistic innovation pioneered by the European New Waves (see Krämer 2005: 1). The film was commercially successful, coming fifth in the top ten box office figures for 1967 after its re-release following critical acclaim in Europe (2005: 106–7). The article in Time concluded that ‘Bonnie and Clyde demonstrated … Hollywood was undergoing a renaissance, a period of great artistic achievement based on “new freedom” and widespread experimentation’ (2005: 1; emphasis added). It thus presciently outlines some of the defining features of the Hollywood Renaissance as it is conceptualised in later critical writing. It is viewed as a golden era of independent filmmaking, a new form of distinctively American modernism, and an epoch abounding in formally innovative and politically subversive films (see Krämer 1998: 303; 2005: 2).

Part of the novelty of the Hollywood Renaissance was its association with a new generation of film directors. Krämer notes that many of the top hits of 1967–76 were directed by newcomers from the interwar generation. These young directors had not come through the studio system but had instead received their training in television and theatre before starting to make films (2005: 82–4). Indeed both Mike Nichols and Arthur Penn worked on Broadway during the 1960s. This partly accounts for their willingness to directly present subject matter that the Production Code would have regarded as too controversial, such as the adulterous affair in

The Graduate (see King 2002b: 32). Krämer’s delineation of the key directors of this period differs significantly from his earlier summary of standard auteurist accounts of the new generation of directors emerging in the 1960s, which focus on ‘the so-called “film school generation” or “moviebrats”’ (1998: 303). The close-knit group comprises Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, Francis Ford Coppola, John Milius, George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. Critics have argued that the experience of formal education in film created a generation of cinematically and theoretically literate directors who styled themselves as auteurs (see Carroll 1982: 52–5; King 2002b: 88–90).

King’s analysis of the textual strategies deployed by films from the Hollywood Renaissance utilises two familiar sets of aesthetic criteria: the modernist and the classical. He offers a detailed analysis of the opening scene of Bonnie and Clyde, drawing attention to two jump cuts: the first while Bonnie (Faye Dunaway) turns away from viewing herself in the mirror and the second as she moves to lie, semi-naked, on her bed. Bonnie ‘[thumps] the bedstead in frustration. She pulls herself up, head framed through the horizontal bars. A sultry pose. The camera lurches awkwardly into a big close-up on her eyes and nose’ (2002b: 11–12). The obvious change of focus in the awkward lurch of the camera coupled with the jump cuts shows Penn utilising the techniques of the French New Wave to create an impression of ‘restlessness, edginess and … sexual hunger or longing’ (2002b: 12). The jump cuts were inspired by Jean-Luc Godard’s À bout de souffle (1960) and are deployed similarly to create a disorientation and uneasiness that forms the tone of the film (see King 2002b: 12, 36–7, 40).

Tonal disorientation is achieved through spatial dislocation created by eschewing some of the rules of continuity editing, specifically the 180-degree rule and matches on action. King argues that classical editing serves to create the illusion ‘of a world that is ordered and comprehensible’ (2002b: 39). Thus, disrupting the classical construction of space through the use of jump cuts has ideological significance. However, Penn’s departure from the classical construction of space is not sufficient to create a properly modernist text. King’s reading charts a course from the modernist to the classical: ‘departures from classical conventions can be seen as expressive devices [if they] are “motivated” by matters of character or narrative. As such they remain within the influential definition of classical style given by David Bordwell’ (2002b: 41). In this way, King re/reads his own analysis of the opening scene of

Bonnie and Clyde – the expressive use of disorientating editing techniques means it actually conforms to the classical paradigm. At stake here is a sense in which the binary of the modernist versus the classical contains and confines the aesthetic possibilities of the film text – it must be one or the other. In failing to be sufficiently modernist,

Bonnie and Clyde becomes classical.

Both King and Krämer are concerned to challenge conceptions of the Hollywood Renaissance as a golden era of politically subversive and/or modernist filmmaking. Krämer’s strategy is to show that this description does not apply to most of the top ten films released between 1967 and 1977. In contrast, King demonstrates that Renaissance films do not conform to modernist standards of subversion. While he acknowledges that some Renaissance films are ‘openly critical of dominant myths and ideologies’, many ‘remain within the compass of dominant mythologies’ (2002b: 45). Indeed, Bonnie and Clyde is seen to update the frontier mythology of the classical western. King notes that The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) and The Parallax View (Alan J. Pakula, 1974) subvert convention by denying their protagonists ‘any possibility of success’ or even a heroic death (ibid.). However, the social and political implications of such endings are ‘entirely negative. No alternative is offered. Diagnosis is not accompanied by a prescription for change’ (ibid.). Thus proper subversion is seen to involve both the deconstruction of the capitalist system and (ideally) the delineation of socio-political alternatives. Once again, the films of the Hollywood Renaissance fail to conform to the standards set by modernist aesthetics.

King’s repositioning of Renaissance films as stylistically classical, rather than modernist, expands the historical boundaries of classical aesthetics, moving the paradigm into the 1960s. Interestingly, although a number of the stylised, self-reflexive aesthetic strategies of Renaissance films could be regarded as postmodern, this period does not tend to be conceptualised in this way. In contrast, New Hollywood has been theorised as both the end of classical aesthetics and the beginning of the post-classical. While the post-classical is often collapsed into the postmodern, this account will note the divergence of some key aesthetic strategies.

New Hollywood

Thomas Schatz defines New Hollywood as the era of the blockbuster – suggesting that the label best applies to the post-1975 period, following the success of Jaws (1993: 9). Schatz parallels his deployment of the title with Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson’s definition of the classical: ‘Both terms connote not only specific historical periods, but also characteristic qualities of the movie industry at the time particularly its economic and institutional structure, its mode of production, and its system of narrative conventions’ (ibid.). I will address the problematic scope of these definitions later. Sheldon Hall notes that the term ‘blockbuster’ originates in 1943–44, referring to a bomb big enough to destroy a city block. Its first use with reference to film occurs on 14 November 1951 in a Variety review of Quo Vadis (Mervyn Le Roy, 1951) where praise for ‘plunging horses and necklines (Hall 2008)’ sets up immediate associations with action, visual spectacle and excess.

While it is clear that Hollywood has a long history of creating large-scale spectacles,

Jaws is positioned as exemplary of New Hollywood for a variety of reasons. Firstly, it is an example of a pre-sold property – the film is based on a best-selling novel – thereby ensuring a pre-existing audience for the movie (see King 2002b: 54). Secondly it conforms to the package unit system of production. The deal was brokered by International Creative Management, who represented the book’s author, Peter Benchley, and ‘the producing team of Richard Zanuck and David Brown [putting] together the movie project with MCA/Universal and

wunderkind director Steven Spielberg’ (Schatz 1993: 17). Finally, and most importantly,

Jaws both initiates and consolidates major changes in patterns of exhibition and promotion. In the roadshow release model, a limited number of prints toured the country and were exhibited at prestige cinemas. Hall notes that ‘publicity costs were typically shared with exhibitors at a local level’ and the film built up a reputation through press reviews and word of mouth during the course of the theatrical run (2002: 21).

Jaws marks a shift to simultaneous release patterns and a significant escalation of promotion. The film was released ‘on 464 domestic screens accompanied by a nationwide print and television advertising campaign’ (ibid.). The cost of the advertising campaign was US$2.5 million, most of which was spent in the week before the film opened. This campaign of saturation booking and advertising became the new norm, each successive blockbuster aiming to be released on more screens with greater publicity, thus driving up the costs of distribution still further (Hall 2002: 21).

Schatz argues that the shift in patterns of exhibition and promotion had the effect of placing ‘increased importance on a film’s box office performance in its opening weeks of release’ (1993: 19). The front-loading of the audience also ensures a film has an opportunity to recoup production costs before being undermined by any adverse publicity (ibid.). The blockbuster thus overcomes a significant disadvantage of the roadshow model, namely the length of time taken to cover the cost of production. The front-loading of the audience becomes increasingly pronounced with contemporary blockbusters aiming to recoup a large percentage of production costs in their opening weekend. King provides the example of Batman (Tim Burton, 1989) which had an estimated production budget of US$30–40 million and grossed US$40 million in its three-day opening weekend (2002b: 56). Profits are also maximised through the creation of multiple platforms of consumption. Schatz notes that ‘Jaws became a veritable sub-industry unto itself via commercial tie-ins and merchandising ploys’ (1993: 18).

The accumulation of further profits through marketing tie-ins, as demonstrated by Jaws, is part of an ever-expanding trend. The substantial profits for Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope (George Lucas, 1977), US$510 million by 1980, were augmented by sales of t-shirts and ‘intergalactic bubble-gum’, the latter grossing US$260,000 in July 1977 alone (see Pirie 1981: 53). King argues that from the 1980s to the early 2000s, the development of ancillary markets became crucial to Hollywood’s economic strategy: ‘a way of increasing revenues [during] a period in which growth in box-office income was outstripped by escalating production and marketing costs and an increasing share in gross profits was claimed by key creative talent’ (2002b: 68–9). Hall notes that throughout the late 1980s and 1990s a blockbuster could ‘earn two to three times its domestic gross’ (2002: 22) through ancillary markets, such as television and home video.

The shift to viewing the blockbuster as one element of an overall marketing strategy that encompasses a number of inter-related products – the book, the soundtrack, the video/DVD, the game, the bubble-gum and the theme park ride – is brought about by the conglomeratisation of the Hollywood film industry. King notes that the major studios – Warner Bros., Disney, Twentieth Century Fox, Paramount, Universal, Sony Pictures/Columbia and DreamWorks – ‘are located within the landscape of large media corporations’ (2002b: 67). This clearly spreads the significant financial risk involved in the production of expensive blockbusters. He traces the way in which the multiple mediums of the

Batman franchise, including comic books, soundtracks and video releases, demonstrate the potential for the development of ancillary markets through conglomeratisation (see King 2002b: 74–5).

The conglomeratisation of Hollywood can be seen as ultimately homogenising, creating a handful of giant corporations whose tentacles are everywhere. Indeed, King argues that New Hollywood displays two axes of integration: the multiple marketing platforms constituting a mode of horizontal integration while ‘old-style vertical integration exists in the combination of production/finance and distribution’ (2002b: 71). This has an effect on the range and scope of alternatives available; ‘corporate Hollywood sets certain limits on what can be achieved. Space for less obviously commercial or more challenging material is determined to a significant extent by the success of the mainstream blockbuster’ (2002b: 83). The takeover of independent distributors/producers by major studios, such as Disney’s acquisition of Miramax in 1993, would seem to indicate that even the innovative is now part of the system (ibid.).

In contrast to King’s picture of homogenisation, Schatz argues that the defining features of New Hollywood are fragmentation and diversification. He parallels the ‘increasingly fragmented entertainment industry’ epitomised by ‘diversified “multi-media” conglomerates’, and its ‘equally fragmented’ products – the blockbusters with their multiform marketing platforms (1993: 9, 10). Importantly, Schatz’s article is formative in the conceptualisation of New Hollywood as post-classical. The ‘vertical integration of classical Hollywood, which ensured a closed industrial system and coherent narrative, has given way to “horizontal integration” of the New Hollywood’s tightly diversified media conglomerates, which favors texts strategically “open” to multiple readings and multimedia reiteration’ (1993: 34). It should be noted that this formulation of the classical significantly reworks Staiger, presenting the studio era alone as the epitome of classical production.

Schatz conceptualises the key aesthetic qualities of the blockbuster as a negation of the classical. The blockbuster does not form an integrated whole and lacks causal narrative structures and effective characterisation. This is because marketing imperatives to create ancillary products have an ‘aesthetic corollary’: ‘films with minimal character complexity … and by-the-numbers plotting (especially male action pictures) are the most readily reformulated and thus the most likely to be parlayed into a full-blown franchise’ (1993: 29). Indeed, the blockbuster is so swamped by ancillary products, it ‘scarcely even qualifies as a narrative’ (1993: 33). The demise of characterisation is also attributed to the new star system. Key players have simply become ‘franchises unto themselves’ (1993: 31), making star vehicles that are devoid of character development. Schatz, like many others, presents the demise of narrative as a logical consequence of the rise of spectacle (1993: 12, 23, 32; see also King 2000: 3; King 2002b: 179). The construction of spectacle as destructive typically reduces it to big-budget special effects, which affect the audience in purely visceral and kinetic ways.

King explores the conceptualisation of the blockbuster as ‘a virtually non-stop roller-coaster “thrill ride”’ (2002b: 185) utilising Fred Pfeil’s quantitative analyses. Pfeil’s graphs set out three models of the relation between narrative duration (horizontal axis) and spectacular events (vertical axis) in a film. The third graph traces the trajectory of the blockbuster, its line charting ‘a series of peaks and troughs resembling [a] roller-coaster structure’ (ibid.). King provides his own quantitative analysis of the central section of Speed (Jan de Bont, 1994), charting the film after Jack Traven (Keanu Reeves) boards the bomb-laden bus. There are a series of problems: the driver is shot, the bus has to negotiate obstacles, from children crossing to hairpin bends, and, most famously, a gap left in the half-built, new freeway. ‘A graphic profile … would depict a line remaining high in the action-spectacle range and showing … rapid sequences of sub-peaks’ conforming to the roller-coaster pattern (2002b: 190). However, King concludes that the quasi-mathematical calculation of spectacle is problematic, arguing that Speed conforms to classical aesthetics in its presentation of a cause and effect narrative chain that is structured around character goals and actions (2002b: 187, 202).

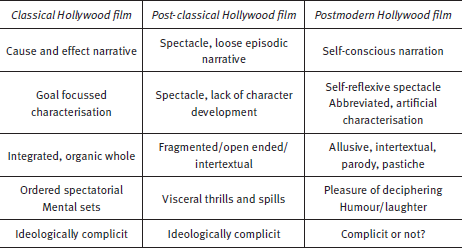

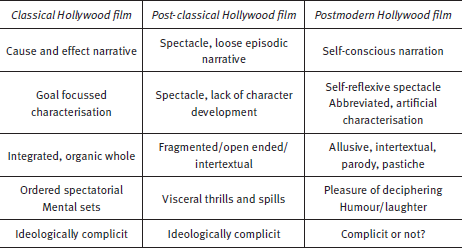

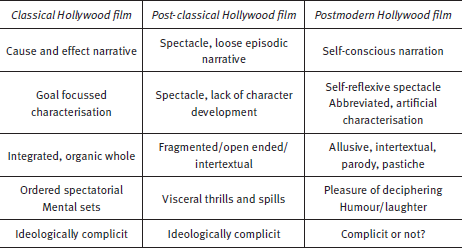

Although Schatz’s model of the post-classical has been frequently criticised (see King 2000; King 2002b; Bordwell 2006), it is widely circulated as a summary of the key aesthetic features of the films of New Hollywood and can be set out in the tabular form below.

| Classical Hollywood film |

Post-classical Hollywood film |

| Cause and effect narrative |

Spectacle |

| Goal focussed characterisation |

Spectacle |

| Integrated, organic whole |

Fragmented/open ended/intertextual |

| Ordered spectatorial mental sets |

Visceral thrills and spills |

| Ideologically complicit |

Ideologically complicit |

The post-classical film displays its characteristic fragmentation through textual strategies, particularly intertextual references and generic hybridity (see Schatz 1993: 18, 22, 34). Bordwell’s vision of the logical, rule-governed processes of classical spectatorship can be pitted against the visceral thrill-rides of the post-classical spectator. At the same time, the post-classical open-ended text does sustain the construction of multiple readings, suggesting the possibility of more complex modes of spectatorship. Both types of text are ideologically complicit for different reasons. The self-effacing narrative techniques of the classical secure its construction of a hermetically-sealed world thereby ensuring it fails to challenge dominant ideology. While the foregrounding of spectacle in the blockbuster might have reflexive possibilities, these are circumvented by its status as one product in a raft of commodities, and thus it epitomises and endorses capitalist ideology.

While the table sets out the key oppositions attributed to classical/post-classical film texts, it is clear from Schatz’s analysis that one pair of aesthetic terms, integration versus fragmentation, play a privileged role in welding the aesthetic to the economic and industrial elements. The aesthetic term thus functions as a crucial metaphor, holding the disparate elements together. Both Schatz and King analyse the rise of conglomeratisation, but each characterises the process differently – as diversification and ever-tighter integration respectively. This demonstrates that it would be equally viable to view the industrial conditions of conglomeratisation as integration, thereby destroying the industrial aspect of a paradigm of the post-classical based on fragmentation. At stake here is the recognition that the metaphor of fragmentation is under considerable strain in the production of the post-classical paradigm.

King’s deployment of classical aesthetics to analyse films of the Hollywood Renaissance and New Hollywood positions Bordwell’s account of classical style alongside historical accounts of modes of production that are seen as a break with the classical, such as the rise of independent production during the 1960s and the conglomeratisation of the 1980s. King thus fundamentally undermines the parallel between ‘aesthetic norms and the mode of film production’ that is the basis of the classical paradigm (Bordwell et al. 1985: xiv). If the products of the conglomeratised New Hollywood display classical aesthetic strategies, they cannot be causally related to classical modes of production. Moreover, the reverse postulation that the creation of classical narratives is a major aim of multi-media conglomerates seems even less plausible. The economic organisation of New Hollywood would suggest that Hollywood’s imperatives are mainly commercial (see King 2002b: 180–1).

Post-classical/Postmodern

Film theorists have taken up different aspects of the post-classical and related them to the postmodern. Linda Williams focuses on the shift in modes of spectatorship, from mental sets to visceral thrills, arguing that they demarcate a key transition from the classical to the postmodern. This shift in viewing techniques is said to be initiated by Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960). The unprecedented murder of the protagonist, Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), half way through the film, effectively deprives the audience of their locus of identification and their normal modes of deciphering narrative. Instead, spectators are left ‘to anticipate “Mother’s” next attack and to register the rhythms of its anticipation, shock, and release’ (2000: 356). Thus Psycho begins the process of recreating spectatorship as a series of visceral thrills and spills, encouraging a ‘“roller-coaster” sensibility’ (ibid.). This postmodern sensibility is further integrated with other aspects of the post-classical, in that it shows a dwindling of spectatorial ‘concern for coherent characters or motives’ (ibid.).

The problem with Williams’ equation of the post-classical and the postmodern is that it constitutes an unusual use of the terminology of the postmodern. Postmodern theory presents the world as a text, one that is constantly constructed and reconstructed through competing discourses, and thus is frequently criticised for its failure to conceptualise the bodily and the visceral except as a series of signs. As a result, the model of the bodily spectator that Williams wishes to promote would not seem to be best served by the label ‘postmodern’. Other endeavours to inter-relate the post-classical and the postmodern centre on the aesthetic strategies of fragmentation and intertextuality. I will explore one of these versions in detail, Roberta Garrett’s analysis of New Hollywood’s relation to the postmodern, which draws heavily on Nöel Carroll’s influential article on allusion in Hollywood cinema from 1982.

Carroll’s article focuses on films made from the 1960s to the early 1980s, thereby conjoining the periods of the Hollywood Renaissance and New Hollywood to form a single era entitled ‘new Hollywood’ (1982: 74–5). He argues that films from this era display a distinctive aesthetic feature – they contain unprecedented quantities of allusion (1982: 51). Carroll defines allusion as an ‘umbrella term’ that includes ‘quotations, the memorialization of past genres, the reworking of past genres, homages, and the recreation of “classic” scenes, shots, plot motifs, lines of dialogue, themes, gestures, and so forth from film history’ (1982: 52). The explosion of allusion in Hollywood cinema is the result of a general enthusiasm for film history that seized America in the 1960s and early 1970s (1982: 54). This was caused by the widespread dissemination of archive Hollywood films through independent cinemas and the medium of television.

This widespread enthusiasm for film history coupled with education at film school resulted in a new generation of cinematically literate directors who style themselves as auteurs (see Carroll 1982: 54–5). Importantly, Carroll initially argues that allusion both draws on and sustains auteurism. For example, some 1970s’ directors are said to refer to Howard Hawks’ films in order to ‘assert their possession of a Hawksian world view, a cluster of themes and expressive qualities that has been … expounded in the critical literature’ (1982: 53). Thus an allusion to Hawks both recreates elements from one of his films’ diegetic worlds and references critical writing on the distinctive perspective of Hawks the auteur (1982: 55). In turn, the use of allusion reconstructs the new directors themselves as auteurs in that they ‘unequivocally identify

their point of view on the material at hand’ (1982: 53; emphasis added). Importantly, in this initial definition, allusion is not equated with ‘plagiarism or uninspired derivativeness’, it is a vital ‘part of the expressive design of the new films’ (1982: 52).

Such allusive texts could only be fully appreciated by a cinematically literate spectator and Carroll develops a two-tier model of the audience: the naïve ‘adolescent clientele’ positioned below the ‘inveterate film gnostics’ who have the cultural capital to play the ‘game of allusion’ (1982: 55–6). Both types of spectator are at variance with the thrill seeker of the post-classical model. Carroll also conceptualises the film text as divided, comprising ‘the genre film pure and simple, and … the art film in the genre film’ (1982: 56). Successful blockbusters, such as Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark (Steven Spielberg, 1981), please both tiers of the audience by offering a ‘loving evocation’ of past genres, imitating and exaggerating the B-movie cliffhanger (1982: 62). The generic allusions in Raiders of the Lost Ark have expressive qualities, producing a nostalgic ‘wistfulness and yearning’ (ibid.). At the same time, the lavish quality of the reconstructions repackage ‘the potboiler prototypes so that they are finally as breathtaking as we want to remember them’ (ibid.). Carroll notes that such celebratory allusionism is neither ironic nor defamiliarising, and concludes: ‘the aesthetic risk of Raiders is that the line between a genre memorialization and tawdry genre rerun … may become all but invisible’ (1982: 64).

Carroll argues that the widespread practice of allusion ultimately changes ‘the nature of Hollywood symbol systems’, charting a movement away from a natural integration of form and content to a system of shorthand: ‘organic expression for a Hawks was translated into an iconographic code by a Walter Hill or a John Carpenter’ (1982: 55). The result is the formation of a specific type of allusion that works via ‘iconic reference rather than … expressive implication’ (1982: 69). The shift away from the natural and expressive to ‘style-as-symbol’ comes to be constructed as a form of decline. This is evident from Carroll’s later comments in which allusion is repositioned as ‘part of a more general recent tendency to strident stylization’ (1982: 78; emphasis added) evident in the films of the new Hollywood.

Carroll’s article constructs two narratives of decline: the shift from natural expression to an iconographic code and the transition from expressive allusion to mere affectation. Carroll’s first, positive form of expressive allusionism is related to a distinctive utopian social project: ‘a desire to establish a new community, with film history supplying its legends, myths and vocabulary’ (1982: 79). However, this utopianism is located firmly in the 1960s and later forms of allusion are in danger of deteriorating into ‘mere affectation [and] nostalgia’ (1982: 80). In this second form, allusion is the practice of the despised

metteur-en-scène rather than the auteur, ‘presenting the artist in terms of ultra-competence rather than genius, as technically brilliant rather than profound, as a manipulator rather than an innovator’ (1982: 80, fn. 16). In this second formulation, allusion is equated with derivativeness.

While Carroll’s article has been taken up to chart the relation between new Hollywood and the postmodern (see Dika 2003; Garrett 2007), he only touches on postmodern aesthetics in a single footnote. He distinguishes between Hollywood allusionism, which is expressive, and postmodern intertextuality, which ‘refers to artifacts of cultural history for reflexive purposes, urging us to view the products of media as media’ (1982: 70, fn. 14). The binary of expressive versus reflexive is problematic given Carroll’s own charting of the decline of expressive allusion and the rise of ‘strident stylisation’ across the era of new Hollywood. Moreover, the characterisation of the reflexive qualities of the postmodern – the foregrounding of the medium itself – sounds more akin to modernist aesthetic strategies.

Roberta Garrett takes up Carroll’s work in order to chart the development of new Hollywood and its relation to the postmodern. She argues that new Hollywood promotes two textual strategies that intersect with those of an emerging ‘popular postmodernist cinema aesthetic’ (2007: 28): allusions to classical texts and generic hybridity. Garrett sets up a three-stage model of allusion that constitutes a key map of the development of postmodern cinema within Film Studies (2007: 33, 42–44). The first two stages roughly correspond to the periodising explored in this chapter: the Hollywood Renaissance followed by the rise of the blockbuster.

Garrett’s model sets out an overall trajectory of decline, following Carroll’s narrative of the degeneration of allusion. There is a ‘first wave of auteurist allusionism – in which new Hollywood directors sought to pay homage to the best of classical and European art cinema’ (2007: 42). This is followed by ‘the blockbuster celebration of older action and adventure forms’, such as

Star Wars and

Raiders of the Lost Ark (ibid.). The third stage of ‘postmodernist self-reflexivity is marked by its range of “lowbrow” subcultural, popular references and specific appeal to … viewers whose formative years were steeped in an unprecedented exposure to classic and contemporary cultural forms’ (ibid.). Thus the key aesthetic feature of post-modern film is the sheer quantity and diversity of intertextual references. Postmodern allusionism is often viewed as undiscriminating, evident from its characterisation as ‘cinematic stew’ or a magpie collection or ragbag of references (Brooker and Brooker 1997a: 90; Booker 2007: 48).

The director who epitomises the third stage is, of course, Quentin Tarantino. Garrett contrasts his eclectic range of lowbrow references – famously gained from working in a video store – with the cine-literate backgrounds of the movie brats. The third form of allusion is the most debased because it constitutes a recycling of all past forms, regardless of their cultural status: ‘it reflects the … film industry’s tendency to plunder, cannibalise and repackage older forms as “classic” largely on the basis of their value as signifiers of the past as opposed to their continued relevance or cultural worth’ (2007: 42–3). The shift in terminology, from auteurist allusionism to mere repackaging, encapsulates both the narrative of decline and the impact of conglomeratisation. Defined as ‘repackaging’, the aesthetic strategy of allusion is simply synonymous with the marketing strategies of the multi-media conglomerates. Like Schatz’s use of fragmentation, the term ‘repackaging’ operates on a metaphorical level, welding together the aesthetic and industrial elements.

The problem with Garrett’s attempt to interweave the decline of allusion and the rise of conglomeratisation is the weakness in the delineation of the second stage. The allusionism of the second stage is characterised as unproblematically celebratory, yet this period marks the beginning of conglomeratisation. Indeed, the strategies of the blockbuster – simultaneous release patterns, saturation booking and the escalation of advertising – both constitute and initiate new extremes of capitalist economics. It is thus not at all clear how the allusionism of films of the second stage escapes the debasement of the allusionism displayed by films from the third stage. Indeed, Carroll’s ambivalence towards tawdry genre reruns suggests they do not (see 1982: 64). If the major difference between films from the second and third stages is simply the sheer quantity and diversity of references, then the transition is purely aesthetic and has no straightforward economic and industrial correlates.

The problems arising from Schatz’s definition of the post-classical and Garrett’s delineation of the postmodern foreground a fundamental issue: namely the sheer impossibility of delineating a single model that could weld together the economic, industrial and aesthetic elements successfully. Schatz’s explicit endeavour to create another version of the classical paradigm thus highlights the untenable scope of the original. Moreover, the presentation of post-classical and postmodern aesthetic strategies as the products of specific historical epochs is undercut by the recognition that only a proportion of the films made during the designated epoch will exhibit such strategies (see Schatz 1993: 35; Garrett 2007: 22). Garrett, like King, contributes to the perpetuation of classical aesthetics, arguing that numerous products of new Hollywood conform to this model (2007: 22).

The argument that new Hollywood films exhibit features of classical aesthetics has the logical corollary of drastically loosening the historical dimension originally indicated by the terminology of ‘the classical’. Indeed, the expansion of the classical era of 1917–1960 from 1917 up to the present day would seem to mark the end of its usefulness as a means of historical classification. Bordwell and Thompson’s demonstrations of the longevity of classical aesthetics focus on editing and narrative construction rather than the means of production, thereby shifting the terms of the original paradigm. Importantly, Bordwell’s defence involves a shift in the formulation of classical aesthetics from a rule-governed process to the rules underpinning the process. No longer (partly) presented as one of a series of aesthetic styles, such as classical versus modernist, Hollywood’s classical aesthetic becomes the rules of narrative and style, forming ‘the default framework for international cinematic expression’ (2006: 12).

Bordwell’s later presentation of the classical as a foundational framework is achieved through parallels with the Italian Renaissance. The classical premises of narrative and/or style established in the studio era are compared with ‘the principles of perspective in visual art’ (2006: 12). In contrast, the aesthetics of the post-classical – displayed by films from directors working after the demise of the studio system – constitute a specific aesthetic style. The post-classical directors’ efforts ‘to respond to the powerful legacy of studio-era cinema’ (2006: 16) are compared with post-Renaissance painters’ attempts to delineate their own styles in the shadow of their illustrious predecessors. Thus Bordwell suggests the strident stylisation of new Hollywood can be paralleled with Mannerism in Italian painting of the sixteenth century (2006: 188). Both exhibit the following key aesthetic features: overt stylisation, self-consciousness and a celebration of artifice (2006: 188–9). Importantly, the foundational principles of the classical remain unchanged by the transition. Indeed, just as the rules of perspective underpin Mannerism, the principles of the classical set up the possibility of a post-classical style.

This shift from aesthetic features to underlying rules can be seen in the analysis of classical narrative. Bordwell’s discussion of narrative experimentation in new Hollywood is grounded by a key question: ‘How could innovations be made comprehensible and pleasurable to a wide audience?’ (2006: 73). The question alters the status of classical narrative; it no longer functions as one type of tightly integrated story structure but rather as a set of rules of storytelling that ensure a narrative is comprehensible. The shift is made possible through a slippage in the precise purview of ‘the rules’. For example, cause and effect is first presented as ‘a premise of Hollywood story construction’ (1985: 13). Its purview is expanded to the audience when it is reintroduced as a chief principle of ‘intelligible exposition’: the means through which a narrative can be understood by the viewer (2006: 93). As a result, films as diverse as Groundhog Day (Harold Ramis, 1993) and Memento (Christopher Nolan, 2000) are repositioned as classical insofar as the viewer is able to construct a fabula that conforms to causal logic (see Bordwell 2006: 78–80, 91–3).

The repositioning of cause and effect as a principle of intelligibility simply foregrounds the highly tenuous nature of its link to the classical. The logical structure of causality and its usefulness for everyday reasoning has a long history within Western philosophy, beginning with Aristotle, thus preceding the model of classical Hollywood cinema by about two millennia. A viewer’s use of causal reasoning to understand narrative does not therefore constitute evidence of the dominance of the classical. Moreover, the reworking of the classical extends the aesthetic aspects of the first paradigm. Classical narration is initially defined by its forward flowing temporality (1985: 45), a feature that would seem to be undermined by the inclusion of

Memento. If most new Hollywood films are basically classical, it is not because they all obey the same fundamental rules, but rather that the aesthetic parameters of the model are being continually reworked, becoming so elastic that the designation of ‘classical’ is applicable to everything. Thus the apparent dominance of

the classical paradigm is attained through the constant reinterpretation of what constitutes the classical, thereby setting up a series of inter-related paradigms under a single name.

Bordwell keeps the term ‘post-classical’ in play in order to rebut the category by demonstrating that the products of new Hollywood are still classical. The eschewal of the post-classical is, unsurprisingly, accompanied by a rejection of the postmodern. Bordwell aims to ‘get past generalizations about blockbusters and postmodern fragmentation’ by showing that such texts adhere ‘to very old canons’ (2006: 35). This involves finding historical antecedents for the blockbuster in the ‘chases, stunts, fights and explosions’ (2006: 108) featured in early classical films, such as Our Hospitality (John G. Blystone & Buster Keaton, 1923). However, the delineation of precedents for the blockbuster’s celebration of spectacle merely repositions the blockbuster as a continuation of trends begun in the historical era of the classical. It does not address the crucial issue, namely that the narrative-dominated theoretical model of classical aesthetics makes it impossible to discern and map the development of such aesthetic trends. Incorporating the blockbuster within the paradigm of classical aesthetics forecloses any mapping of the different roles played by spectacle in different genres of film. This is the point at which the expanded paradigm of the classical ceases to be of instrumental value, its all-encompassing nature prevents the charting of different types of aesthetics.

The Meanings of ‘Post-’

Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson present their first paradigm of the classical as a model of scientific reasoning that is based on unbiased sampling (1985: 10). However, their view of the history of Hollywood cinema as the rise of a single paradigm, including production contexts, technological innovation and aesthetics, creates an overarching narrative that betrays the legacy of Enlightenment theorising. One of Jean-François Lyotard’s key examples of a grand narrative is Marxist theory. It offers an overarching telos of progress, the eventual overthrow of capitalism by the workers themselves, alongside a key foundational term, economics, which acts as the site of truth. Within the classical paradigm, the overriding metaphors of unity and integration serve to weld together the disparate industrial and aesthetic elements. The rhetoric of norms, rules and standards also functions to secure the singularity of the paradigm, acting as a bridge between Bordwell’s aesthetics and Staiger’s account of standardisation in production. Moreover, Bordwell’s conceptualisation of classical aesthetics positions narrative as the key foundational term – it operates as the privileged site of textual meaning. Bordwell’s later paralleling of studio-era Hollywood and the Italian Renaissance creates a pinnacle of attainment within the narrative of the classical, thereby outlining a trajectory of rise and fall.

Theorists who argue for the end of the classical set up competing but similarly overarching narratives: Schatz’s charting of the post-classical, Carroll’s delineation of the demise of allusion in new Hollywood, and Garrett’s account of the advent of the postmodern all offer teleological narratives of inexorable decline. The problem in all these cases is the attempt to construct the new era as a clearly delineated epoch. In these conceptualisations of the post-classical and the postmodern, the term ‘post’ ‘has the sense of a simple succession, a diachronic sequence of periods in which each one is clearly identifiable’ (Lyotard 1992: 90). Each new epoch is also characterised as a complete break: ‘a conversion: a new direction from the previous one’ (ibid.). Lyotard argues ‘this idea of a linear chronology is itself perfectly “modern”. It is at once part of Christianity, Cartesianism and Jacobinism: since we are inaugurating something completely new, the hands of the clock should be put back to zero’ (ibid.). For Lyotard, the modernist conception of a complete break is particularly suspicious: ‘this rupture is in fact a way of forgetting or repressing the past … repeating it and not surpassing it’ (ibid.).

Within Film Studies, narratives of conversion, such as Schatz’s model of the post-classical, have been swiftly followed by narratives of continuity – Bordwell’s defence of the classical. However, combatting narratives of conversion through the assertion of continuity also involves the suppression of the past. The key aesthetic features inadequately conceptualised within the original classical paradigm – intertextuality, spectacle and self-reflexivity – are repressed once again by the reassertion of the dominance of narrative. Importantly, the failure of every attempt to contain the aesthetic strategies of Hollywood cinema within specific historical periods, from the classical to the postmodern, shows that the division of aesthetic styles into discrete epochs simply cannot be done. The logical corollary of the widely held claim that classical aesthetics can be found in films outside the classical period (see Schatz 1993: 35; Garrett 2007: 22) is to accept that post-classical and postmodern aesthetic strategies can be found in texts made during the classical period.

Lyotard’s critique of the use of the term ‘post’ to indicate successive periods, leads him to argue that postmodern aesthetics cannot be equated with or confined to a postmodern era. For Lyotard, the postmodern continually erupts within the modern, destroying any construction of a linear timeline. Postmodern art differs from modern art in its relation to the sublime. Postmodern art is ‘that which searches for new presentations … in order to impart a stronger sense of the unpresentable’ (1984b: 81). Lyotard continues his analysis of the non-linear temporality of postmodern art forms by charting their relation to the formation of rules. ‘A postmodern artist or writer is in the position of a philosopher: the text he writes, the work he produces are not in principle governed by pre-established rules, and they cannot be judged … by applying familiar categories to the text or to the work. Those rules and categories are what the work of art is itself looking for’ (ibid.). Thus the incommensurability of the creation of postmodern texts and the later critical/theoretical understanding of their aesthetic strategies are part of the temporal paradox of the postmodern. Such postmodern texts help to bring new rules into existence: ‘The artist and the writer [work] without rules in order to formulate the rules of what will have been done’ (ibid.).

I want to draw on Lyotard’s conception of the temporality of postmodern aesthetics as a means of solving the problems arising from unsuccessful attempts to periodise aesthetics within Film Studies. Utilising Lyotard enables us to begin to chart the ways in which texts from different epochs in Hollywood history utilise postmodern allusive and intertextual strategies. The acknowledgement that Hollywood’s aesthetic strategies do not conform to neat periodisations does not imply that all historical periodisation is impossible. Charting local changes to specific conditions is essential to constructing the economic, industrial and technological histories of Hollywood cinema. Within this century-long period, historical demarcation points, such as the studio era or the decade of the Hollywood Renaissance, can be helpful.