This last chapter focuses on one major postmodern theorist, Linda Hutcheon, and examines the ways in which her work challenges the nihilistic models explored in chapter two. While Jameson’s work has been taken up in relation to Hollywood film, Hutcheon’s literary model is only rarely considered. This chapter will show how she provides a range of aesthetic concepts that facilitate an appreciation of the many textual strategies deployed by postmodern films, thereby offering a means of escaping the self-fulfilling conceptions of textual degeneracy and emptiness set up by the nihilistic models.

The chapter begins with Peter and Will Brooker’s analysis of circling narratives, setting out the ways in which their affirmative postmodern aesthetics draw on Nietzsche’s model of the eternal return. Brooker and Brooker demand that their readers ‘think with more discrimination and subtlety about the aesthetic forms and accents of postmodernism’ (1997: 91). This chapter rises to their challenge by combining key aesthetic concepts from Hutcheon’s work, including postmodern parody and complicitous critique, with the Lyotardian non-linear model of postmodern film aesthetics set up in chapter one. The chapter ends with a detailed analysis of the diverse postmodern aesthetic strategies presented by four films: Sherlock Junior, Bombshell, Kill Bill: Vol. 1 and Kill Bill: Vol. 2, the last two hereafter abbreviated to Vol. 1 and Vol. 2.

Brooker and Brooker’s analysis of the initial critical dissention over Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994) draws together a series of familiar criticisms. They focus on the controversy caused by the film’s presentation of violence, noting that both critical dismissal and approval of Pulp Fiction are likewise couched in the language of emptiness and loss. The film is castigated for being ‘empty of social and moral content’, a mere ‘ragbag of film references’, or, alternatively, celebrated as a knowing pastiche of cinematic violence that is so resolutely intertextual it is ultimately meaningless (1997: 90–1). Brooker and Brooker argue that the terminology attests to the critics’ adherence to a traditional romantic humanist aesthetic which ‘requires its bad twin in order to sustain it’ (1997: 90). Positioning post-modern aesthetics as a bad twin reveals the logic of negation underpinning the definitions of the familiar aesthetic categories.

Unsurprisingly, Booker’s later analysis of Pulp Fiction as the consummate postmodern film reprises the terminology of vacuity and superficiality. However, the initial diatribe against its moral emptiness has given way to a vocabulary that provides its superficiality with a level of cultural cachet. Thus, Booker extolls Pulp Fiction, as ‘a perfect illustration … of pastiche’ (2007: 89) and ‘one of the most self-consciously cool films ever made’ (2007: 13). In a shift from film to director, the intertexts are reduced to ‘signs of Tarantino’s famed coolness’, which are then said to operate as ‘in-jokes to help audience members feel cool themselves’ (2007: 89). The final shift from director to audience deploys the terminology of cool to trivialise the process of meaning construction involved in tracing intertexts. At stake here is Booker’s indebtedness to a Jamesonian model of pastiche in which recycling is equated with repackaging and thus demonstrative of aesthetic bankruptcy.

Brooker and Brooker’s article sets up an alternative to this purely negative conception of the aesthetics of recycling, through an analysis of repetition and intertextual referencing in circular and circling narratives. Their article focuses on

Pulp Fiction’s ‘episodic, circling … structure’ (1997: 91), presenting it as paradigmatic of a new form of postmodern narrative. Quoting the work of Edward Said, Brooker and Brooker suggest that post-modernity is marked by the disappearance of social and political structures that are underpinned by a model of linear narrative; thus, ‘narrative which posits an enabling beginning point and a vindicating goal, is no longer adequate for plotting the human trajectory in society’ (1997: 95). While for Said, this marks a closing down of options – ‘There is nothing to look forward to: we are stuck within our circle’ – Brooker and Brooker argue that the episodic, non-linear structure of

Pulp Fiction constitutes a series of circling mini-narratives in which key characters, specifically Jules (Samuel L. Jackson) and Butch (Bruce Willis), ‘gain new purpose and a sense of long-term direction’ (ibid.). Thus

Pulp Fiction is said to offer a model of circular repetition, which is opened out to encompass new possibilities.

Jules can be regarded as an exemplary instance of Brooker and Brooker’s model of repetition as recreation. Jules’ re-evaluation of his life and work is brought about by his and Vincent’s survival of a volley of six bullets discharged at close range by an unknown and unexpected antagonist. The attack leaves the pair entirely unscathed, leading Jules to read the incident as a miracle. Brooker and Brooker chart Jules’ transformation with reference to a key quotation that the character delivers three times across the film: Jules ‘sets [out] to reinterpret the text of Ezekiel 25:17 which he customarily recites before a killing to new ends. If he has been the “evil man” … he believes he can become the blessed man who “shepherds the weak through the valley of darkness”’ (ibid.).

Brooker and Brooker’s analysis of repetition and change focuses on Tarantino’s recreation of generic character types, such as the hit-man and the boxer. They argue that he ‘reinvents and extends these conventions, exposing their abstract “cartoon”-like rudiments, adding unexpected dialogue, fluent monologue, a concentrated intensity … or hyperbole of character’ (1997: 96). In this way, the characterisation of the pair of hit-men departs from the confines of the pulp tradition through ‘the undertow of gossipy, bickering dialogue’ (ibid.). The theme of being ‘granted new life’ thus occurs at the level of the narrative – Jules’ decision to bear witness; at the level of characterisation – Tarantino’s recreation of stock generic types; and finally, at level of the casting, in that the success of Pulp Fiction revived ‘the dipping, repetitive careers of actors such as Willis and Travolta’ (ibid.). Unsurprisingly, the sophisticated model of repetition and change sustains a positive analysis of audiences who trace the complex deployment of intertextual references within and across Tarantino’s oeuvre (1997: 93–4).

Importantly, Brooker and Brooker repeatedly characterise their circular model of revival and reinvention in terms of affirmation (1997: 92, 97, 99). Their ‘inventive and affirmative mode’ of postmodern aesthetics is said to be exemplified by the revival of Mia (Uma Thurman) after her overdose on Vincent’s (John Travolta) heroin (1997: 97). Her treatment with a shot of adrenalin, which Vincent administers as though stabbing a vampire in the heart, provides a brief foray into Gothic horror that unsettles the film’s generic base. Taking issue with a critical reading of the scene as demonstrative of the ways

Pulp Fiction showcases graphic violence, Brooker and Brooker argue it offers ‘the most graphic illustration of the film’s theme of re-invention and rebirth’ (ibid.). The inter-linking of affirmation, repetition and new life is also evident in the film’s manipulation of chronology in order to ‘return us to better moments’ (ibid.). The revival of Vincent in the final section offers a non-linear reprise of Mia’s return from the dead, thereby affording the audience the chance ‘to consider from a new angle what might have been’ (1997: 99). This is both an opportunity to reappraise the meaning of Vincent’s life and death and an invitation for the audience to consider how they might choose to rewrite the ending of the story.

While Brooker and Brooker do not trace the theoretical underpinnings of their own circular model, their inter-linking of affirmation and repetition strongly recalls Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return. For Nietzsche, the dynamic of the eternal return is not the endless repetition of the same but rather a repetition in difference. In spatial terms, it is not the two-dimensional, dead end of a closed circle, but rather a three-dimensional circling back and forth to create ‘a series of loops each of which constitute an emerging pattern, thus opening up the possibility of creating new relations’ (Constable 2005: 105) between the points on the circling structures. Looping back and forth is a mode of returning to key points from different directions, thus each circling structure offers the possibility of looking backwards and/or forwards from a new vantage point. In this way, the logic of the eternal return is linked to a reviewing of the past/future, which takes the form of a shift of perspective.

Sarah Kofman utilises the eternal return in her analysis of the role of the artist, the creator of appearances, in Nietzsche’s work. Providing her own translation of a key quotation from

The Twilight of the Idols: ‘appearance means reality repeated

once again, as selection, redoubling, correction’ (1988: 189), Kofman draws attention to the way in which the creation of art is a mode of repetition. This is not a mimetic model, in which art is a representation of reality; instead the creation of art is an imitation of the creative power of nature. Moreover, the relation between art and nature sets up a fundamental distinction between those appearances/fictions that devalue nature, such as the ascetic ideals of Christianity in which physicality and the material world are devalued in order to promote a living for death, and true art ‘in which appearance is willed and the world repeated … to enhance the creative capacity … of life’ (1988: 181). The positive valuation of physicality/materiality to be found in true art is key to its affirmative power: ‘art

wills for life yet again its eternal return in difference, a dionysian mimetic power at one with creation and affirmation’ (ibid.; emphasis added).

Brooker and Brooker’s utilisation of the vocabulary of affirmation is not reliant on the relation to nature that underpins Nietzsche’s writing on art and the eternal return. However, there is an interesting parallel between the logic of negation that characterises fictions that devalue nature and the writing on postmodern aesthetics examined in chapter two. For Nietzsche, Christianity is based on a perverse ‘ressentiment towards life’, nature and materiality; ‘the ascetic ideal is negative and destructive’, indeed the key concept of ‘the fictional, perverse world [of Paradise] is defined purely negatively’ (Kofman 1988: 180, 181). At the same time, ‘perversion is always also inversion and reversion’, a logic that results in the formation of a closed circle thus marking the null point of thinking – an inability to generate new categories and concepts. In the same way, the definition of postmodern aesthetics as the negation of modernist and/or humanist aesthetics simply promulgates a series of aesthetic concepts that are defined as necessarily debased. Thus the ostensible lack of creativity observed in postmodern art forms is simply a reflection and expression of the nullity of the logic of ressentiment that underpins the negative definition of the aesthetic concepts themselves.

Brooker and Brooker’s model of postmodern aesthetics is a mode of affirmative theorising that goes beyond the logic of negation in order to open up ways of appreciating and describing the aesthetics of recycling. This is not the simple substitution of the positive for the negative, a celebration of all postmodern art forms as necessarily valuable. They take up the vocabulary of affirmation and differential repetition to create a theoretical model that is capable of mapping different types of postmodern artworks. ‘If some examples of postmodern art are at once scandalous and vacant, or “merely” playful, others are innovative and deeply problematising … cultural postmodernism is various and contradictory: fatalistic, introverted, open, inventive, and enlivening’ (1997: 94).

Linda Hutcheon

Affirmative theorists of the postmodern share a characteristic conceptualisation of cultural postmodernism as both diverse and contradictory (see Brooker and Brooker 1997; Hutcheon 1988 and 1989; Collins 1989). Unlike Baudrillard and Jameson, such theorists resist presenting postmodernity as a single, self-perpetuating system, whether in the form of the endless circulation/floatation of capital, power, language and theory, or the unfolding of the logic of late capitalism. Hutcheon situates the post-modern in relation to two major dominants – economic capitalism and cultural humanism – thereby avoiding collapsing it into a single system. She notes that both discourses offer different and incompatible accounts of the individual’s relation to wider society: humanism presents ‘the individual as unique and autonomous’, capable of self-determination through choice; while economic capitalism reveals ‘the pretence of individualism (and thus of choice) is in fact … mass manipulation, carried out … in the name of democratic ideals’ (1989: 13). As a result, the de-centring of the individual subject that is said to be typical of postmodernism can be seen to have very different effects when considered in relation to the contradictory constructions of the individual offered by the two discourses. In this way, conceptualising postmodern culture as a plurality of incompatible and conflicting discourses means that any postmodern theoretical move can be understood in a variety of ways and thus, in turn, each move also initiates a myriad of unexpected effects.

Contradiction plays a central role in Hutcheon’s analysis of the post-modern: ‘postmodernism is a fundamentally contradictory enterprise: its art forms (and its theory) at once use and abuse, install and then destabilize convention in parodic ways, self-consciously pointing both to their own inherent paradoxes and provisionality and, of course, to their critical or ironic rereading of the art of the past’ (1988: 23). On this model, recycling is not the spiralling movement of the eternal return in difference but rather a pendulous swing to and fro in which both aspects, the repetition of the same and the differential reworking of past forms, constitute the two apexes of a single, swinging movement. This doubleness, evident in the simultaneous recapitulation and reworking of the art of the past, sustains a sense of the profoundly equivocal nature of postmodern art forms. While Hutcheon is keen to recognise the importance of both halves of the postmodern paradox of conservatism and innovation, she also opens up ways of appreciating the political and critical potential of the postmodern aesthetics of recycling.

Hutcheon’s own mode of theorising draws attention to the centrality of paradox within her conception of the postmodern and the specific paradoxes that structure her own position. The symmetry between her vision of postmodern theory and her own theorising gives her writing the characteristic self-consciousness of postmodern texts. Hutcheon draws attention to the provisional nature of her position by presenting it as an addition to a long line of fictions told by key postmodern theorists, including Brian McHale, Baudrillard and Jameson (1989: 11). Unlike Baudrillard who offers a plethora of incompatible stories demonstrating the proliferation of fictions within the hyperreal, Hutcheon unfolds one particular story, her own version of the postmodern featuring doubled perspectives and equivocal texts.

Like Baudrillard, Hutcheon argues that the postmodern marks the end of viewing representation as purely mimetic. For Baudrillard, the shift away from viewing the image as a copy of the real sets up a series of alternatives, including the fourth phase of the seamless, self-referentiality of the ‘pure simulacrum’ (ibid.), which dissolves reality and inaugurates the hyperreal. Hutcheon stages the conflict between reality and the simulacrum in different terms, as a ‘confrontation … where documentary historical actuality meets formalist self-reflexivity and parody’ (1989: 7), keeping both contrary elements in a state of perpetual play. For Baudrillard, the precession of simulacra also marks the primacy of the image seen in its defeat of other elements including reality, truth, meaning and all objective value. In contrast, for Hutcheon, the postmodern awareness of the power of images and fictions offers a different way of analysing their generative and constructive capacities, as ‘systems of representation which do not

reflect society so much as

grant meaning and value within a particular society’ (1989: 8). While Baudrillard constructs the loss of the objective ground of value as the end of all possible value systems, Hutcheon focuses on diverse, socio-cultural constructions of value. Importantly, this key shift enables her to argue that the postmodern is not synonymous with the loss of meaning and value but rather provokes discussion and analysis of how cultural meanings and values are constructed and negotiated.

For Hutcheon, the continual tension between the contrary elements of historical reality and textual reflexivity generates two key postmodern projects: ‘an investigation of how we make meaning in culture’, and an inter-related endeavour to ‘“de-doxify” the systems of meaning and representation by which we know our culture and ourselves’ (1989: 18). While both projects draw on deconstructive techniques, the second is explicitly political. To ‘de-doxify’ is to challenge long-held opinions and beliefs, ‘to point out that those entities that we unthinkingly experience as “natural” (… capitalism, patriarchy, liberal humanism) are in fact “cultural”’ (1989: 2). Drawing on feminist work from many different areas of aesthetics, Hutcheon concludes that ‘representation can no longer be considered a politically neutral and theoretically innocent activity’ (1989: 21). Crucially, this informs her sense of the vital issues at stake in postmodern art works: ‘Postmodern art cannot but be political, at least in the sense that its representations – its images and stories – are anything but neutral, however “aestheticized” they appear to be in their parodic self-reflexivity’ (1989: 3). Hutcheon is thus able to avoid Baudrillard’s sweeping conception of the postmodern as the end of politics because she does not simply focus on party politics (right versus left) but instead offers a feminist Foucauldian conception of the diffuse, complex interactions interlinking everyday activities with broader structures of social power.

For Hutcheon, postmodern art works have the capacity to present ‘politicized challenges to the conventions of representation’ (1989: 17) thereby offering a form of critique. However, the equivocalness of the postmodern text means that it cannot be regarded as purely subversive. Both ‘a critique … of the view of representation as reflective (rather than as constitutive) of reality … it is also an exploitation of those same challenged foundations of representation’ (1989: 18). The precariousness of postmodern critique is paralleled with the equivocal positioning of third-wave feminist theory: ‘both inside and outside dominant ideologies, using representation … to reveal misrepresentation and to offer new possibilities’ (1989: 23). Thus both postmodern and feminist texts deny the possibility of a pure space of critique that is securely positioned outside the system. The major difference between them is that the former are deconstructive while the latter are concerned to advocate forms of political action.

For Hutcheon, the equivocal nature of the postmodern text requires theorists to maintain a doubled perspective; however, she is also concerned to challenge theorists who define postmodern aesthetics entirely negatively, such as Fredric Jameson and Terry Eagleton. Both ignore ‘the subversive potential of irony, parody and humour’ in postmodern artworks because they treat it as the opposite of serious art, rather than looking at the role humour plays ‘in contesting the universalizing pretensions of “serious” art’ (1988: 19). Importantly, Hutcheon refuses to define post-modern playfulness as simply synonymous with superficiality and frivolity: ‘to include irony and play is

never necessarily to exclude seriousness and purpose in postmodern art’ (1988: 27).

Interlinking humour and contradiction, it is unsurprising that Hutcheon nominates parody as ‘a perfect postmodern art form’ (1988: 11). Its doubleness can be discerned in its etymology, the Greek word ‘para’ meaning both near/beside and counter/against, thus parody ‘paradoxically both incorporates and challenges that which it parodies’ (ibid.). While examples of parody from the eighteenth century are typically designed to ridicule the original, Hutcheon argues that postmodern parody has ‘a wide range of forms [from] witty ridicule to the playfully ludic to the seriously respectful’ (1989: 94). Her championship of parody leads her to challenge Jameson, whom she holds responsible for the ‘dominant view of postmodern parody as trivial and trivializing’ (1989: 113). She takes issue with his general definition of parody, arguing that it is entirely derived from the eighteenth-century model of ‘ridiculing imitation’ (1988: 26). This limited definition is then replaced by its opposite, postmodern pastiche, which is defined as ‘neutral or blank parody … “the random cannibalization of all the styles of the past”’ (1988: 26, 27).

On Jameson’s model the blank emptiness of pastiche is over-determined in that the heterogeneity of aesthetic styles available overwhelms and smothers the normative, which underpins the possibility of true parody, while, at the same time, the model of the individual subject who is able to create great works of art is no longer viable. In sharp contrast, Hutcheon argues that postmodern parody questions ‘our humanist assumptions about artistic originality and uniqueness’ (1989: 93). Thus, importantly, parody is not linked to a model of Romantic authorship – a send up of the truly individual styles exhibited by the great modernists – but instead is seen as a mode of writing in which the very concept of an individual style is itself questioned and contested. Parody is not linked to a set of norms – against which the individual stylistic tics of modernist authors can be sent up – but rather to a broad history of prior texts that it both evokes and reworks at the same time. Thus, for Hutcheon, parody is critical, historical and political: ‘a value-problematizing, de-naturalizing form of acknowledging the history (and through irony, the politics) of representations’ (1989: 94).

Hutcheon’s insistence on the historicity of postmodern parody is clearly intended to challenge Jameson’s account of postmodern aesthetics as nothing more than the ‘value-free, decorative, de-historicized quotation of past forms’ (ibid.). She argues that Jameson’s analysis of the nostalgia film as purely destructive of the real historical past is reliant upon a specific definition of ‘Marxist History’ with its ‘positive utopian notion of History and … faith in the accessibility of the real referent of historical discourse’ (1989: 113). Like Jameson, Hutcheon argues that History in the form of ‘a naturally accessible past “real”’ (ibid.) no longer exists. However, in sharp contrast, Hutcheon goes on to argue that history, in the sense of multiple and conflicting constructions of the past, is alive and well. Importantly, history is not effaced and displaced by texts, texts are absolutely crucial to its construction: ‘documents, eye-witness accounts, documentary film footage, or other works of art [are] our only means of access to the past’ (ibid.).

While Hutcheon challenges Jameson’s account of the nostalgia film, she is indebted to his conception of pastiche as a lesser aesthetic form, utilising it for intertextual works that do not aspire to the double encoding of complicity and subversion fundamental to postmodern parody. ‘Most television, in its unproblematized reliance on realist narrative and transparent representational conventions, is pure commodified complicity, without the critique needed to define the postmodern paradox’ (1989: 10). Other examples of pastiche include the plethora of allusions to traditional film genres in rock videos and the ‘vague and unfocused references’ (1989: 12) to classical architecture in shopping malls. Following Jameson, pastiche is characterised as a failure to quote properly; however, the terms through which it fails are different. For Jameson, pastiche fuses the aesthetic and the economic – its banal recycling expresses the logic of late capitalism. For Hutcheon, pastiche is a failed aesthetic because it is insufficiently paradoxical, rigorously deconstructive, and/or reflexive in its mobilisation of past forms.

Like Brooker and Brooker, Hutcheon offers a

range of types of post-modern text, from the vacant to the de-doxifying, encapsulated by the terms ‘pastiche’ and ‘parody’ respectively. While her wholesale dismissal of television is highly problematic, she does offer a broad definition of parody that is clearly applicable to a wide range of mass cultural products, including film and television: ‘What postmodern parody does is to evoke what reception theorists call the horizon of expectation of the spectator, a horizon formed by recognizable conventions of genre, style, or form of representation. This is then destabilized and dismantled step by step’ (1989: 114). In her analysis of film, Hutcheon utilises this definition to set out a spectrum of different forms of parody, from the light, Brian De Palma’s

Phantom of the Paradise (1974), to the overtly deconstructive, Maximillian Schell’s

Marlene (1984).

Both Booker and Hutcheon note the wide range of references utilised in Phantom of the Paradise, including The Phantom of the Opera (Gaston Leroux, 1911), Faust (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1999) and, more fleetingly, Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960) and The Picture of Dorian Gray (Oscar Wilde, 1992). The plot concerns a demonic record producer, Swan (Paul Williams), who steals a song from composer/singer Winslow Leach (William Finley) and frames him for drug dealing. Escaping from prison, Leach is mutilated in an accident and thus becomes the phantom, haunting Swan’s club, The Paradise. Recognised by Swan, Leach is persuaded to sign a contract in blood in exchange for having his music produced as he wanted, but Swan then double-crosses him. Booker views the film as a bleak satire of the music business, reading Leach’s supporting act to ‘The Juicy Fruits’ as a send up of the 1950s nostalgia craze that took place in the 1970s (2007: 63). Hutcheon briefly addresses the ways in which the film reworks its major and minor intertexts arguing that it engages with ‘the politics of representation, specifically the representation of the original and the originating subject as artist: its dangers, its victims and its consequences’ (1989, 115). Her reading pieces together the diverse traditions of representation evoked by the intertexts, thereby offering a rebuttal of more extreme models of the centrifugal fragmentation of the postmodern text (see Booker 2007: 5). Importantly, Hutcheon’s model allows her to trace both thematic overlaps and disparate contradictory elements; the post-modern text is thus neither utterly fragmented nor ultimately reconstructed as a seamless whole.

The humorous way in which

Phantom of the Paradise positively brandishes its references is the basis of its critical potential: ‘Multiple and obvious parody like this can paradoxically bring out the politics of representation by baring and thus challenging convention’ (Hutcheon 1989: 115).

Marlene offers a rather different mode of parody in its rigorous deconstruction of the documentary genre. ‘It opens asking the question: “Who is Dietrich?” and the question is revealed as unanswerable’ (ibid.). The film is metacinematic in its foregrounding of the means of production, showing the process of editing film clips and documentary footage, the reconstruction of Dietrich’s flat, and featuring a directorial commentary on the difficulties of piecing together the available material. The commentary is interspersed with extracts from aural interviews with Dietrich, attesting to the director’s difficulties, the elderly star offering tangential and often entirely inconsistent answers to his questions. The reflexive aesthetic strategies draw attention to the fragmentation of the star as subject and thus foreground the fictional nature of the humanist ideal of the coherent self that underpins the genres of biography and documentary (see Hutcheon 1989: 115–16).

Ultimately Hutcheon’s positive view of the critical potential of the range of forms that constitute postmodern parody is reliant on her take up of deconstructive rather than modernist definitions of critique. Her indebtedness to deconstruction is clear: postmodern parody’s destabilisation of the conventions of genre, style and forms of representation serves as a means of denaturalising and thus questioning the status quo. This leads her to define postmodern film, as ‘that which … wants to ask questions (though rarely offer answers) about ideology’s role in subject-formation and in historical knowledge’ (1989: 117). Importantly, the shift to asking questions enables Hutcheon to avoid confining critique to the provision of answers in the form of either pure utopian spaces (see Jameson 1991: 48) or action plans of social alternatives to capitalism (see Booker 2007: 40, 148–50, 188).

The rejection of pure spaces outside the system as a vantage point from which to conduct critique or the ideal end product of critique is central to Hutcheon’s position. Critique is always conducted from the inside, at once part of and different from the system that it simultaneously rein-scribes and calls into question. This doubled positioning also underpins Hutcheon’s analysis of the relation between film and the capitalist system. ‘Postmodern film does not deny that it is implicated in capitalist modes of production, because it knows it cannot. Instead it exploits its “insider” position in order to begin a subversion from within, to talk to consumers in a capitalist society in a way that will get us where we live, so to speak’ (1989: 114). This move is vital in that it sets out a key way in which mainstream Hollywood cinema might participate in deconstructive forms of critique. Moreover, this model of subversion acknowledges Hollywood’s position within corporate capitalism while preventing it from functioning as the end point of discussion (an economic and textual ‘bottom line’), thereby challenging the numerous analyses of postmodern films that take commercial success to be straightforwardly indicative of aesthetic and critical failure.

Hutcheon’s embrace of paradox, her deployment of deconstruction and indebtedness to feminism play key roles in the formulation of her model of the postmodern. Importantly, these resources enable her to move beyond the logic of negation, providing her with ways out of Baudrillard’s and Jameson’s nihilistic analyses of the destruction of reality, history, aesthetics and critique. She offers an affirmative mode of theorising that is expressed through the new formulations of postmodern parody and ‘complicitous critique’. Like Brooker and Brooker, she offers an affirmative model of postmodern aesthetics that provides a means of analysing and addressing a range of postmodern texts.

Re/thinking Hollywood’s Aesthetics

While Hutcheon’s work does provide the means for rethinking the aesthetic and critical potential of postmodern Hollywood cinema; her account of the derivation of postmodern aesthetics, particularly in relation to film, is more problematic. Her complex analysis of the development of post-modern aesthetics ultimately presents it as following on from modernism. ‘Postmodernism challenges some aspects of modernist dogma: its view of the autonomy of art and its deliberate separation from life; its expression of individual subjectivity; its adversarial status

vis à vis mass culture and bourgeois life … But, on the other hand, the postmodern clearly also developed out of other modernist strategies: its self-reflexive experimentation, its ironic ambiguities and its contestations of classic realist representation’ (1988: 43). In this quotation, key aesthetic strategies of the postmodern are presented as the legacy of modernism, and, importantly, it is this legacy that constitutes the basis of the critical/interrogative capacity of postmodern texts.

Two key proponents of entirely uncritical forms of classic realist representation are television and studio-era Hollywood films (see Hutcheon 1989: 106–7). Hutcheon builds on William Siska’s analysis of ‘traditional Hollywood movies about movie-making’ such as Sunset Boulevard (Billy Wilder, 1950) and Singin’ in the Rain (Gene Kelly & Stanley Donen, 1952), asserting that they simply ‘retain the orthodox realist notion of the transparency of narrative structures and representations’ (1989: 107). Siska is said to argue in favour of a modernist cinema that eschews spatial and temporal coherence and breaks down classical cause and effect narrative structures. Hutcheon’s summary of his position replicates the oppositional presentation of the classical versus the avant-garde/modernist text, specifically the opposition realism/narrative versus non-realist anti-narrative, presented by E. Ann Kaplan’s table of polarised filmic categories explored in chapter one. These well-worn oppositions form the basis of Hutcheon’s analysis of the ambivalence of postmodern cinema, constructing it as a Derridian third term that flits across the binary divide of classic realism and modernism, subverting and reinstating the conventions of the former by deploying and amending the techniques of the latter.

Importantly, in viewing the reflexivity of films such as

Sunset Boulevard and

Singin’ in the Rain as fundamentally contained by the conventions of realist representation, Hutcheon offers a model of postmodern cinema whose forms of parody are seen to have absolutely no relation to the reflexive and parodic structures offered by films of the studio era. The subordination of reflexivity to narrative parallels Bordwell’s argument (discussed in chapter one) in which key examples of baring the device, such as the ‘You Were Meant For Me’ number from

Singin’ in the Rain, were deemed to be merely momentary instances of artistic motivation and thus ultimately subsumed by compositional motivation (1985: 22–3). However, it seems clear that Hutcheon’s conception of light parody with its playful deconstruction of style, genre and past/present forms of representation is present in numerous Hollywood films from the studio era. It would seem more logical to acknowledge the connections between the comic deconstruction of stardom offered by the opening of

Singin’ in the Rain, where Don Lockwood’s catchphrase, ‘dignity, always dignity’, is juxtaposed with flashbacks of his far from dignified beginnings as a knockabout stuntman, referencing Douglas Fairbanks’ career, and the reflexive, intertexual satire of the music industry presented in

Phantom of the Paradise. Moreover, both films foreground the techniques of sound recording, playing with different forms of disjunction between the speaking/singing subject (Lena Lamont and the Phantom respectively) and their accompanying voices.

Importantly, tracing connections between Hutcheon’s form of light postmodern parody and the aesthetic strategies of studio-era Hollywood is not tantamount to arguing that there is no such thing as postmodern aesthetics. As argued in chapter one, adopting a Lyotardian model means that postmodern aesthetics can erupt at any point across the history of Hollywood. Moreover, Hutcheon’s careful definitions of postmodern parody, intertextuality, reflexivity, and compromised critique form the basis of an affirmative postmodern aesthetic that constitutes a lens through which we can view the products of Hollywood differently. Taking up her conception of the paradoxical, compromised postmodern text offers a way of avoiding the hierarchical logic that privileges narrative at the expense of all other textual elements. Taken seriously, her model enables a tracing of the ways in which deconstructive and reflexive moments might intersect with and be developed through narrative. At stake here is a repositioning of postmodern aesthetics as the aesthetic strategies of mass culture, which recognises that the products of mass culture are capable of offering a variety of forms of complicitous critique.

Tracing a new non-linear history of postmodern aesthetics in Hollywood is beyond the scope of this book; however, I want to look briefly at two very different examples of reflexive, intertextual parody: Sherlock Junior (Buster Keaton, 1924) and Bombshell (Victor Fleming, 1933). The former offers a celebrated example of comedy created through a reflexive play with the conventional forms of continuity editing (see King 2002a: 45). By contrast, the latter is an often overlooked comic example of a film about making films. The readings will show that taking up key concepts from Hutcheon’s postmodern aesthetics facilitates an appreciation of each film’s complex textual strategies, enabling the first to offer a de-doxification of film spectatorship, while the second presents a deconstruction and reconstruction of film stardom.

In

Sherlock Junior Buster Keaton plays a young film projectionist who is studying to be a detective. He gets engaged to the girl (Kathryn McGuire) only to be framed for the theft of her father’s watch by a rival suitor. Failing to capture the real thief, he returns disconsolate to the cinema and falls asleep while projecting the film

Hearts and Pearls. In his dream, the original cast of

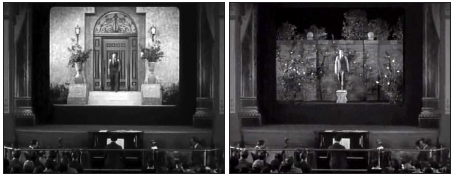

Hearts and Pearls are replaced by his former fiancée, her father, their handyman and the successful suitor, who proceeds to menace the girl in the confines of her bedroom. Attempting to rescue her, the projectionist’s dream double bounds into the screen world, only to be forcibly ejected by his rival. The long shot presents the film’s audience, the orchestra in the pit and the entire ‘celluloid’ screen, emphasising the hero’s trajectory across the screen’s frame. This doubled framing also underscores the doubled reflexivity of the dream film of the projected film within the film.

The scene changes to an exterior shot and the hero re-enters the dream film only to find he cannot get into the house. As he turns away from the front door and walks down the central steps, there is a cut to a long-shot of the garden. His forward momentum is continued via an action match but the change of setting means he now falls forward off a centrally placed garden bench. Leaning backwards to sit on the bench, the scene changes to a busy street and he falls back off the kerb into the traffic. The abrupt spatial transitions continue: ‘walking along the road, he almost goes off the edge of a cliff; peering over the cliff, he finds himself looking close up at a lion; wandering around he is relocated into a desert and suddenly a train rushes closely past’ (King 2002a: 45). There are eight cuts to different urban and natural locations from the city to the sea, finally returning to the garden and the scene fades to black.

The abrupt changes of location draw attention to the cuts, while the matches on action bring the disparate elements together to comic effect. The first transition, from the exterior shot of the house to the garden, sends up the convention of cutting from exterior to interior presented by the first two shots that are shown from the original

Hearts and Pearls: an exterior shot of a large mock Tudor mansion and a medium shot of a man in evening dress putting some pearls in a safe. The eight cuts draw attention to their key function as a mode of ellipsis, a means of omitting irrelevant information, and foreground the work of the viewer in inferring the physical relation between spaces. While the medium shot of the safe is comfortably read as taking place inside the mock Tudor house, the unexpected transition from the front door step to the garden forces the viewer to search for connections between the spaces – the ornate architecture of the walled garden with its espaliered trees is congruent with the imposing doorway and steps – thereby drawing attention to the work that is required to construct connections. The next seven cuts are transitions that defy any endeavour to read the spaces as interconnected, thereby mocking the whole process. Throughout the entire series of eight cuts the first rows of the auditorium and orchestra pit remain visible in front of the screen showing the dream film. The doubled framing makes overt the dream film’s reflexive deconstruction of both conventions of continuity editing and viewers’ techniques of reading.

The fade out in the garden is followed by a fade in to the couple in the bedroom and the camera tracks forward so that the dream film fills the entire frame. On discovering the theft of the pearls, the father calls for ‘the great detective Sherlock Holmes’, who is played by Keaton. The presentation of Holmes’ methodology within the house, eyeballing the suspects and declining all offers of information, is comic in its complete failure to conform to the techniques of painstaking forensic investigation and logical deduction set up by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Sherlock Junior is one of a large number of silent film parodies in which the great detective is presented as less than competent, beginning with the Mutoscope peepshow Sherlock Holmes Baffled (1900) (see Barnes 2002: 156).

Sherlock Junior overtly references its dramatic intertexts by changing the Dr Watson character’s name to ‘Gillette’. William Gillette was an actor-manager who wrote the first play inspired by Conan Doyle’s characters, which was produced across America and Europe from 1899 to 1907. The play utilises two short stories: ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’ and ‘The Final Problem’, diverging from them in presenting Holmes as a romantic hero who eventually ‘gets the girl’, and thereby reconstructing ‘the detective as hero-adventurer’ (Barnes 2002: 128). Keaton’s Sherlock both conforms to and departs from the heroic: a succession of accidents that showcase the star’s acrobatic virtuosity enable him to rescue the daughter of the house from kidnappers but the rescue mission ends with both of them floundering in a lake once their car/boat sinks. William Gillette himself played the role of the great detective at the age of 63 when the play was transferred to the screen in

Sherlock Holmes (Arthur Berthelot, 1916).

Sherlock Junior evokes and reworks the now lost earlier film by presenting the character of Gillette as an older man who is a master of disguise and demoting him to the role of assistant. Thus the film deploys its intertexts to both evoke and displace another Sherlock, constructing a succession in which William Gillette’s Holmes is surpassed by the youthful exuberance and physical virtuosity of Keaton’s Sherlock Jr.

The film’s final scene recalls the reflexivity of its formal play with the conventions of editing. Awakened from his dream, the hero is reunited with the girl who has successfully proved that he did not steal her father’s watch. There is a cut from a long shot of him standing beside her in the projection booth to a medium shot of him looking out through the framed window of the projection box towards the film, now playing the original Hearts and Pearls. The hero looks directly into the camera, towards the viewer, seeking inspiration from the film. There is a cut to a long shot of the auditorium and the film within the film in which a young couple are also reconciling and the girl’s partner leans towards her and pats her hand. This is followed by a medium shot of the projectionist noting the moves admiringly and proceeding to perform the same actions. The pattern of shot/reverse-shot continues as the awkward and inexperienced hero follows his debonair on-screen counterpart: kissing the girl’s hand, placing a ring on her finger and finally kissing her. Keaton imitates all the gestures to comic effect, swinging his shoulders from side to side to indicate youthful embarrassment and almost doing a double take at the thought of enacting the kiss, which takes the form of a very brief, chaste peck on the mouth.

The mimetic model of life comically imitating art is complicated by the framing of the medium shots in which Keaton appears to look directly at the audience, incorporating them within a relay of gazes and thereby adding a further level of mimesis in which the real viewers might also imitate the filmic character’s imitation of art. The complex mimetic model is abruptly shattered by the last shots from

Hearts and Pearls. The on-screen couple embrace and there is a fade to black followed by a fade in on an established family comprising mother, father and two children. The following shot of the hero shows his complete bafflement at this unforeseen turn of events, foregrounding his inability to immediately imitate it! The film thus reinscribes and calls into question the adequacy of the mimetic model as a means of analysing film spectatorship. The foregrounding of ellipsis in the final fade out and fade in explicitly draws attention to what is not shown, recalling the earlier sequence of cuts and summarising the film’s utilisation and deconstruction of the conventions of editing. Importantly,

Sherlock Junior is both comic and thought-provoking, utilising reflexivity, doubling and intertexts to offer a most enjoyable parody of Holmes and to deconstruct the means of representation.

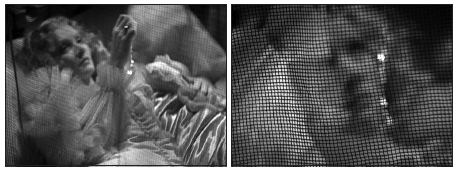

Bombshell offers a deconstruction and reconstruction of stardom in its overtly reflexive presentation of the sex symbol, platinum blonde Jean Harlow in the role of ‘It Girl’ film star Lola Burns. The fast-paced comedy explores the role of fan magazines and the media in the construction of stardom, referencing and parodying MGM’s campaigns for Harlow. The opening montage sequence displays newspaper headlines featuring the private life of Lola, magazines such as

Photoplay and

Modern Screen piling up hot off the printing press, and commercial tie-ins, including hosiery, face powder and perfume, linking the star’s image to the women who purchase and use the products. The frequent showers of gold coins consolidate the clear presentation of the star as commodity. The use of two brief clips of Harlow embracing Clark Gable incorporates the star’s films within the repertoire of the fictitious Lola.

The film footage is intercut with a series of close-ups of its spectators, each of whom is shown with their head slightly tilted to one side gazing coyly upwards at the embrace unfolding on the screen. The range of spectators, women and men, from adolescent to elderly, shows a vast fan base; while their identical worshipful attitudes construct Lola as a screen goddess. There is a wipe across the screen and a crane shot up to an apartment window followed by two dissolves, the dream-like transition linking a medium close-up of a young woman with a close-up of a male fan both day-dreaming about Lola. There is a third dissolve to a long shot of an exotic locale where satin-clad Lola is reclining on a low chaise, her lover seated on the floor beside her, while behind them a black servant waves a huge white feather fan. Two further shots of day-dreaming fans are superimposed over the long shot. The second fades and Lola embraces her lover. The editing indicates that the exotic scenario is a projection of the fans’ fantasies, which both recall and send up the Orientalism of exotic studio locales, the play on the feather fan and bright whiteness of the star’s hair comically exaggerated by an unexpected swan swimming in the foreground.

The fans’ fantasy is humorously juxtaposed with the scene that follows in Lola’s mansion, depicting ‘the reality’ of the star’s life. Lola is first presented as entirely glamorous, her beautiful face visible as she nestles beneath the satin covers of a huge bed, protesting about being woken at 6am. Her breakfast juice is delivered and her conversation with the new butler, whose name she misremembers, attests to the chaotic nature of the household. Matters worsen with the arrival of a trio responsible for preparing her for the day’s shoot, the hair-dresser and make-up artist talking continuously while attempting to do her hair and make-up simultaneously. Pulled in two different directions, Lola sits in the centre of the bed endeavouring to finish her juice, which spills all over her negligee. The final shot of the scene shows her far from glamorous: covered in juice, half made up with her hair falling all over her face.

The first scene contains numerous references to Harlow’s screen roles. The introduction to Lola in her bed recalls the presentation of Harlow’s character, Kitty, in George Cukor’s Dinner at Eight (1933). The telephone conversation with Lola’s secretary, Mac (Una Merkel), in which she reiterates the director’s instructions for Lola to wear ‘the white dress without the brassiere’ overtly references well-known aspects of Harlow’s costuming, beginning with her breakthrough film Hell’s Angels (Howard Hughes, 1930). In Platinum Blonde (Frank Capra, 1931) Harlow wears a series of ‘tight-fitting, see-through satin gowns and nightgowns with no undergarments’ (Jordan 2009: 41). The most overt film reference in Bombshell is a scene in which Lola goes to the studio to do retakes on Red Dust (Victor Fleming, 1932) drawing on Harlow’s performance as Valentine.

In the second scene of

Bombshell, Lola appears in a long white chiffon dress with matching hat. The soft drapes of the flowing chiffon accentuate her lack of bra and draw attention to the movement of her breasts as she walks down the stairs. The contrast with Lola’s previous appearance, covered in orange juice, emphasises the labour that goes into creating Burns’/Harlow’s star image. The division between Harlow’s on-screen star persona and her – equally constructed – private persona forms the reference point for the rest of the scene. Lola’s greeting to her father on finding him sneaking into the house utilises slang expressions: ‘You old rooster! You’ve been out all night and you’re still boiled!’ Her forceful, Chicago-accented delivery of these lines is contrasted with the upper-class English enunciation that she puts on for the journalist, Miss Carroll (Ruth Warren), who arrives to do an early morning interview on the star’s ‘early life’. Lola’s father (Frank Morgan) joins the interview, consolidating the sense of pretension by making improbable claims to extensive acreage in South Illinois. Susan Ohmer notes Jean Harlow’s ‘own “origin story” was firmly upper middle class and Midwestern. The

Los Angeles Times referred to her as a “Kansas City Society Girl” who nearly lost all her inheritance because her grandfather disapproved of Hollywood’ (2011: 176). The film’s parody of the construction of an upper-class Midwestern background references and sends up Harlow’s private persona, foregrounding its status as a construction.

Bombshell revolves around Lola’s arguments with the studio’s head of publicity, Space Hanlon (Lee Tracy), for his orchestration of salacious publicity to promote her role as a ‘Bombshell’ within the popular press. After he arranges for her escort, Marquis Hugo (Ivan Lebedeff), to be taken to jail, Lola demands that Space be fired from the studio. He visits her, claiming to have been fired, and says that he has finally provided her with publicity of which she will approve – an interview with the women’s magazine, Ladies Home Companion. Lola rings to have him reinstated at the studio, unaware that he never actually lost his job. The incongruous shift of publicity from bombshell to champion of domestic values references the abrupt change in MGM’s publicity campaigns for Jean Harlow following the suicide of her second husband, Paul Bern, in September of 1932, after two months of marriage (see Ohmer 2011: 182, 191); ‘They flooded the newspapers and fan periodicals with pictures of Jean in her kitchen, pictures of her in the garden with her pets, pictures of her covered with a huge apron engaged in baking a cake’ (Davies 1937: 31).

Lola’s costume for the publicity photographs in the kitchen is a fitted mid-calf-length dress whose lines are entirely spoiled by the additions of a huge white bow at the throat and a white apron. Her demonstration of prowess in the kitchen comprises spearing a boiled potato with a large cooking fork and wonderfully announcing: ‘I just love baked potatoes, don’t you?’ The interviewer, Mrs Pittcomb (Grace Hayle), is entirely uncritical, telling Lola that she has conformed to her expectation of meeting a ‘sweet unspoiled child’. Mrs Pittcomb then asks if Lola yearns for ‘the Right of all Womanhood’ and on seeing her bemused expression, clarifies: ‘the patter of little feet’. Lola responds by clasping both hands to her bosom as though in prayer and gazing upwards soulfully while affirming that she does want children. The pose parodies the discourse of the sanctity of motherhood espoused by women’s magazines, which is drawn from the Christian tradition.

The pose is repeated across the scene, while Lola gazes soulfully at a picture of a horse and foal. When the director, Jim Brogan (Pat O’Brien), arrives at the mansion Lola suggests that they pick up their romance, marry and have children. While enthusiastic about marriage, Jim dismisses her desire for children as a moment of theatricality. He flips the bow on her dress saying: ‘What’s the idea of this fancy dress costume?’ and expresses a wish to film her as she takes up her Madonna-esque pose. Later, Jim returns to the mansion to discover that Lola has taken his joking suggestion that she adopt an orphan literally. He repeats his offer of marriage so that she can have a child of her own, only to be rebuffed by Lola who now wants to adopt instead, saying: ‘It’s different now. It’s gone beyond anything fleshy!’ Lola’s rebuff references and sends up the Christian depiction of motherhood as a pure spiritual state beyond the material, her preference for adoption over child-bearing foregrounds the incoherence of the ideal by taking it to its logical conclusion. The theatricality of her performance of the Christian vision of the maternal de-doxifies this traditionally naturalised category and it is here that the film’s parody is at its most subversive. At the same time, the film’s presentation of the complete incompatibility of Lola’s two roles, mother versus ‘It girl’, exhibits the polarised logic of the Virgin/Whore dichotomy. While Space’s question: ‘Do you think I want my bombshell turned into a rubber nipple?’ continues the film’s denaturalisation of the maternal, it also reinforces a binary logic of feminine types, thereby demonstrating the film’s compromised critique of a broad history of representation.

Space sabotages Lola’s endeavour to adopt by orchestrating a fight between Jim Brogan and Marquis Hugo at precisely the moment at which she is being interviewed by two respectable women from the foundling home to assess her eligibility as a parent. The fight is covered by the avidly awaiting press to whom Space suggests appropriate headlines, such as: ‘Two Lovers Brawl In Burns’ Home’. As the Marquis and his lawyer go to the mansion with the intention of filing lawsuits against Lola and Jim, the audience are aware Space is misrepresenting the reasons for the brawl. The film thus presents the salacious publicity of the bombshell as fictitious, and by extension, suggests that the less savoury coverage of Harlow’s private life following Bern’s suicide, is similarly orchestrated. Lola’s loss of the chance to adopt leads to an outburst in which she condemns Space, Mac and her family as ‘a pack of leeches’, making clear her status as a commodity that is exploited for profit. The scene links Lola’s commercial exploitation by the studio and the press with her economic exploitation by both her household staff (Mac wears Lola’s clothes and holds parties at the mansion) and her own family (subsidising Pops’ and Junior’s endless bouts of drinking and gambling). Lola resolves to withdraw her labour and disappears.

Lola flees to a spa in Desert Springs and, just like her fans in the film’s first montage, pursues a romantic fantasy of escape that is based on the movies. Her new suitor, Gifford Middleton (Franchot Tone), is an aristocrat and poet, who showers her with mellifluously-delivered compliments that become ever more extravagant, the height being the wonderfully involved metaphor: ‘Your hair is like a field of silver daisies. I’d like to run barefoot through your hair!’ Lola’s delighted response to his professions of love foregrounds their theatricality: ‘Not even Norma Shearer or Helen Hayes in their nicest pictures were ever spoken to like that!’ Lola and Gifford’s romance meets with opposition from his highbrow, aristocratic parents, whose patent disapproval of both the movie industry and Lola’s family causes it to end. The interlude parodies the language of romance presented in drawing-room comedies, the pervasive sense of theatricality preparing the spectator for the later twist when it is revealed that the Middleton family are three stage actors and the entire romance has been orchestrated by Space in order to get Lola to return to work.

The presentation of Lola’s relation to capitalism is complicated in that she is both its success story, surrounded by the accoutrements of wealth, and unable to control the profits of her own labour. She is presented as a worker within the film industry and its chief commodity, her image being instrumental to the successful sales of products and magazines. Unlike Harlow’s previous characters, Lola is unable to capitalise on her commodification as a sex symbol because it is presented as a construct created by the industry and the press, which she embodies (to an extent) but does not control. Thus the role of Lola differs from Kitty in

Dinner at Eight whom Jessica Hope Jordan reads as a gold-digger who successfully trades on her sexuality to attain a luxurious lifestyle (2009: 31–3). This figure of the ‘hyper-feminine woman … utilizes commodity logic for her own personal profit

and … escapes the deadening bonds of conventional wage labor’ (2009: 33) ultimately commodifying her own body to pursue her own pleasure. Jordan argues that both Kitty and Helen from

Hell’s Angels are examples of a contradictory combination of agency within commodification/objectification (2009: 55–65). Importantly, both characters differ from Lola in having clearly demarcated goals and a consistency of purpose. While Lola’s costumes, such as the long white chiffon dress, present her as a sex symbol, she is utterly capricious and her admirers are not in thrall to her but pursuing their own schemes: the Marquis is after her money, ‘Gifford Middleton’ wants a debut in pictures and even Space wants the studio to continue making a profit. Thus the reflexive presentation of the sex symbol within the industry and the farcical comic narrative creates a character who enjoys more success and less agency than Harlow’s previous roles.

The film offers a complex deconstruction and reconstruction of Harlow’s star persona. It draws on the intertexts created by publicity to send up the star’s upper middle class ‘origin story’; at the same time Lola’s rejection of the Middletons and reconciliation with Pops and Junior reaffirms her working-class origins, which are typical of Harlow’s on-screen characters. Bombshell sends up the fans’ vision of the star as exotic goddess, positioning Lola alongside her fans as a worker within a large industry who escapes work via a romantic fantasy constructed by and through the movies. The fake romantic interlude also invests Lola’s and Space’s relationship with a level of integrity, their banter and arguments are typical of the ‘lively and combative style of screwball’ (King 2002a: 56) and thus indicate their compatibility. Harlow’s shift from narratives of seduction into screwball met with very positive reviews. The Atlanta Constitution praised her performance, saying ‘her first opportunity at almost unadulterated comedy and … the platinum-haired menace is amazingly competent in the difficult work’ (cited in Ohmer 2011: 187). In drawing on and sending up Harlow’s image as ‘It girl’, Bombshell provides a distance from the role that enables an appreciation of the star as an actress whose fast-paced delivery and comic timing are praise-worthy. Like the circling structure of the farce in which Space and Lola reunite to fight again, the film facilitates a reappraisal of Harlow’s star persona, drawing attention to qualities that are usually placed in the background: her capacity for hard work, directness and sense of humour, while reflexively demonstrating the process of deconstructing and reconstructing her image.

The theatrical presentation of feminine types across

Bombshell dedoxifies particular ideals of femininity by presenting them as constructions. However, Lola’s endeavours to embody these differing ideals, with varying degrees of success, and the shifting reconstructions of Harlow’s star persona do not correspond to Hutcheon’s model of extreme subjective fragmentation exemplified by the multiple and contradictory variants of Dietrich in

Marlene (1989: 115–16). Harlow as Lola offers a range of performances of diverse forms of femininity, from motherhood to ‘It Girl’. The roles are performed in a variety of ways pivoting the obviously theatrical – motherhood and the female romantic lead of drawing room comedy – against the roles that Lola/Harlow performs more successfully, those of ‘It Girl’, working-class girl made good, and screwball heroine. Lola’s characterisation across the film relies on the viewer responding to Harlow’s performance and key star intertexts in order to position some of her acts as more authentic than others: for example, working-class identity over upper-class identity, the screwball comedy with Space over the romance with Gifford. Harlow’s performance as Lola in

Bombshell can be seen as a series of acts that deconstruct and reconstruct both the character and public/private aspects of her star persona. Importantly, the shift to the surface provided by the film’s foregrounding of performance is not simply synonymous with lack of depth. Harlow as Lola offers a play of surfaces that intersect and overlap thereby creating moments of authenticity.

Kill Bill

Kill Bill offers an extraordinary variety of aesthetic strategies that foreground its status as a film about film and places its female hero within a history of representation. Edward Gallafent rightly notes that the opening of

Kill Bill: Vol. 1 immediately announces its status as ‘a film that will foreground cinematic techniques’ (2006: 101). It draws attention to ‘past and present technologies’ by juxtaposing the ‘fuzzy sound and wobbly image of the Shawscope and “Our Feature Presentation” screens’ with the immaculately detailed black and white close-ups of the Bride’s bloodied face and the ‘high quality of modern sound reproduction [in] Nancy Sinatra’s performance of “Bang Bang”’ (ibid.). The opening also offers a model of self-conscious narration. The credits introduce the actors/stars who feature ‘as the deadly viper assassination squad’ in the following order: Lucy Liu as O-Ren, Vivica Fox as Vernita Green, Michael Madsen as Budd, Daryl Hannah as Elle, and David Carradine as Bill. This order initially aids the deciphering of the hand-drawn, encircled ‘2’ that appears beneath the typed title, ‘Chapter One’ in that the first chapter depicts the killing of the second deadly viper on the cast list. The ending of chapter one offers the first shot of Beatrix’s own list, entitled ‘Death List Five’, with the encircled ‘2’ beside Vernita’s name, which is then crossed out. The reflexive gesture draws attention to the re-ordering of the narrative events, O-Ren’s name is already crossed out. The alignment of Beatrix’s fifth Death List with the cast list suggests that the protagonist is in the process of ordering and re-ordering the narrative.

While it is possible to rearrange the narrative events of Kill Bill to form a chronological fabula, the division and distribution of the chapters across the two volumes invite a non-linear analysis. Indeed, Gallafent’s reconstruction of the fabula draws attention to the chiming elements and his analysis of three key worlds can be reformulated in terms of the presentation of the hero (2006: 103–7). Both films show Beatrix adopting the role of ‘educator to instructor, or even disciple to master’ and becoming the possessor of ‘extraordinary powers’ (2006: 107): swordsmanship and Pai Mei’s techniques. These powers are particularly evident during the killing spree at the end of Vol. 1, and the aftermath of the failed assassination of Budd and successful killing of Bill in Vol. 2. The hero is presented in relation to motherhood: as the pregnant bride, as the mourner of a child presumed to have been born dead in Vol. 1, and as the mother of a living child in Vol. 2. The rhyming structures draw attention to the radical difference in tone of the two films, which has been noted by critics (see Gallafent 2006: 107; Booker 2007: 95).

Kill Bill abounds with quantities of intertexual references, which vary considerably in their scope and significance. Chapter two sees the arrival of the sheriff investigating the crime scene at the chapel in El Paso, played by Michael Parks in a brief reprise of his role as a Texas Ranger in

From Dusk Till Dawn (Robert Rodriguez, 1995). The sheriff’s accurate analysis of the crime scene rapidly establishes his status as a trustworthy observer. The scene presents a series of close-ups of Beatrix’s face taken from the sheriff’s point-of-view. The first is green-tinted, due to the sheriff’s sunglasses, and appears to present the bride in an advanced state of decomposition. The shot references

Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958) and the green tint used to present Kim Novak’s final transformation from Judy to Madeleine (the woman Scottie loves whom he believes to have died falling from a church tower). The necrophiliac aspect of obsessional love re-emerges in the sheriff’s speech as he gazes appreciatively at Beatrix’s dead face: ‘Look at her: hay coloured hair, big eyes, she’s a little blood-splattered angel.’ The film cuts back to the close-up of the bride for the last three words of the speech, the words explicitly cuing the viewer to look through the splatters of bright red blood and see the dead angel beneath. This is comically undercut by Beatrix suddenly demonstrating that she is still alive by spitting blood into the sheriff’s face!

The sheriff’s invitation to the viewer – to look through the blood splatter and see the angel beneath – is important because it draws attention to the way in which Uma Thurman is filmed across

Kill Bill. Gallafent draws on interview material in which Tarantino refers to

Kill Bill as his version of

The Scarlet Empress (Josef von Sternberg, 1934), paralleling the endless close-ups of Uma Thurman with von Sternberg’s presentation of Marlene Dietrich (2006: 120). While the blood-splattered bride might seem a long way from the beautifully lit, groomed perfection of Dietrich, the close-ups combined with the verbal cue set up a particular way of reading the splatter as a veil that both covers and displays the beauty of Thurman’s facial structure.

The Scarlet Empress contains three key scenes where a veil is foregrounded to the point of almost obliterating the view of Dietrich’s face beneath it: the wedding, the aftermath of the birth of the heir, and the final rejection of a former favourite. In the second, Catherine contemplates a jewel, a reward for providing an heir to the throne and there is a cut to a close-up that foregrounds the grain of the veil while drawing attention to the sculpted lines of Dietrich’s cheekbones beneath. For Mary Ann Doane, the veil’s play between what is seen and not seen is a model of seduction and thus ‘foregrounding [its] grain … merely heightens the eroticism, makes [the woman] more desirable’ (1991: 73, 74). Thurman’s veils become increasingly dense: from the artful blood splatter of

Vol. 1 to the engrained grime of dust and mud in

Vol. 2. While the visceral substances forming the veils do not appear to invite touch, Bill’s response at the beginning of

Vol. 1 is to clean up Beatrix’s face before shooting her himself, thereby combining eroticism and sadism. The references to Hitchcock and von Sternberg also serve to construct Tarantino as the latest in a long line of distinguished film directors famously obsessed with their blonde leading ladies.

Beatrix is repeatedly presented as apparently dead or near death across

Kill Bill. The credits for

Vol. 1 end with a shot of her prone profile in silhouette against a light-coloured background, her posture and stillness suggesting she has been laid out for burial. The shifting colour palettes of the close-ups of the apparently dead angel foreground the livid contrast between the red blood and white pallor of her face in the second. The dissolve from the sheriff’s bloodied face to Beatrix in the coma ward of the hospital offers yet another shift, from bright extremes of colour to subdued blue tones in which the now clean, still Beatrix appears grey, cadaverous and, if possible, even more dead.

Vol. 1 abounds in images of death that utilise an iconography of stillness, slenderness and whiteness that can be linked to Bram Dijkstra’s conception of the ‘consumptive sublime’.

Dijkstra argues that the late nineteenth-century cult of invalidism flourished because the social and economic status of middle-class men was measured by the conspicuous leisure and ‘helpless elegance’ of their wives (1986: 27). Invalidism was the zenith of feminine helplessness, requiring considerable economic support while also indicating the virtue of the sufferer. In ‘an environment which valued self-negation as the principal evidence of women’s “moral value,” women enveloped by illness were the physical equivalents of spiritual purity’ (1986: 28). Following the equation of feminine virtue with self-abnegation, ‘true sacrifice found its logical apotheosis in death’ (ibid.). Artistic depictions of such women drew on a specific visual vocabulary of illness presented by sufferers of tuberculosis (1989: 28–9). The cult of the ‘consumptive sublime’ was signified by extreme slenderness, a languishing state of physical degeneration, and bloodless pallor (1989: 29). Dijkstra notes in passing that ‘the fad of sublime tubercular emaciation … has continued to serve as a model of what is considered “truly feminine”’ to the present day (ibid.).

The presentation of Beatrix’s comatose state in the hospital utilises the signifiers of the consumptive sublime, the lighting emphasising her hollowed cheekbones while the broad lines of the bed draw attention to her long slenderness. However, Beatrix’s passivity is not a state of spiritual purity, but, instead, a desperate vulnerability. She is nearly assassinated by Elle and subjected to dreadful sexual exploitation by Buck who repeatedly rapes her comatose body before pimping it out to other men. One of the film’s intertextual references sets up a key contrast between gendered presentations of the inactive body. Following her escape from hospital, Beatrix sits in the back of Buck’s Pussy Wagon, willing her legs to work by repeating the words: ‘Wiggle your big toe.’ The phrase is spoken and sung to Frank ‘Spig’ Wead (John Wayne) by ‘Jughead’ Carson (Dan Dailey) in

The Wings of Eagles (John Ford, 1957). The scene shows Spig lying on his front, looking down at a mirror to view his immobile toes. The positioning of Wayne’s inactive, prone body emphasises its capacity for action, the muscular breadth of the star’s famous shoulders prominently displayed. In contrast, Beatrix is shot from the front, her long legs taking up the length of the back seat, their slenderness emphasised by the loose width of the blue scrubs and her voice-over comment on their atrophied state. Wayne’s body is displayed as an elegy to active masculinity, like a fallen oak, it is a reminder of lost power. The presentation of Thurman’s face and body draws on the consumptive sublime, her recovery is a move away from a model of femininity based on physical degeneration and passivity.

As Gallafent notes, it is significant that the sexual violence to which Beatrix is subjected is not directly represented; the mosquito bite that wakes her acts as a metaphor for other forms of penetration, both sexual (Buck and the Trucker) and medical (Elle’s syringe full of poison) (2006: 107). While Vol. 1 foregrounds its indebtedness to films of the 1960s and 1970s from the opening credits onwards, the refusal to directly present sexualised violence runs counter to the era being evoked. Peter Krämer argues that the greatly increasing levels of sex and sexual violence in Hollywood films from 1967 onwards reached their peak between 1971 and 1973 with films such as A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971) and Deliverance (John Boorman, 1972) (2005: 55). Moreover, the containment of Beatrix’s recollection of Buck’s abuse to his announcement of his name and intentions means the events of chapter two do not conform to a rape-revenge narrative, a form which also emerges during the 1970s (see Clover 1992: 137). While Beatrix’s attack on Buck is sequentially positioned as retribution, it constitutes a restoration of her former identity. The slow-motion presentation of Beatrix rearing from ground-level, cutting Buck’s Achilles tendon, before trapping his head in the door, visually reconstructs her as ‘black mamba’.

Chapter three presents the story of O-Ren Ishii’s revenge on her parents’ killer, the

yakuza boss Masumoto, in the form of Japanese

animé. The shift from live action foregrounds the mode of storytelling and the chapter offers a further meditation on the presentation of screen violence. The acutely stylised forms of blood-letting – the father becomes a geyser of blood while the mother’s blood showers gently onto O-Ren’s face as she hides beneath the bed – draws attention to their generic status. Writing of the mother’s death, Gallafent argues that the

animé form facilitates the provision of ‘images that would be overwhelmingly vicious if presented in live action’ (2006: 108). While chapter two does not directly represent sexual violence of a challenging nature, specifically the rape of a comatose woman, the shift to

animé allows sexual and violent images ‘impossible within the conventions of censorship … the 11-year-old Oren [

sic] astride the body of the paedophile

yakuza boss as she kills him’ (ibid.). Importantly, the shift in the mode of storytelling draws attention to the kinds of violence

Vol. 1 does represent, and the forms they take, positioning the film’s presentation of violence within a history of representation.

The soundtrack for the violent deaths of O-Ren’s father and mother is Luis Bacalov’s melodious theme tune for the spaghetti western, Il Grande Duello (Giancarlo Santi, 1972). Hiding beneath the bed, O-Ren almost gives herself away with a single ‘whimper’ that appears as words on the screen. After her mother’s death, the wailing sound of the amplified harmonica acts as a substitute for the girl’s own voice, articulating her unexpressed grief, loss and desire for vengeance. The use of this musical instrument to convey a child’s voice and these emotions references Once Upon a Time in the West (Sergio Leone, 1969), another spaghetti western, in which ‘Harmonica’ (Charles Bronson) pursues Frank (Henry Fonda) for killing his brother. The main difference between the films is that Vol. 1 uses Bacalov’s music to convey O-Ren’s emotions in one scene, whereas Ennio Morricone’s score for Once Upon a Time in the West provides the laconic Harmonica with an expressive voice, a mode of mourning for his brother, that grants the character emotional depth in accordance with a psychological model of trauma.

Chapter three’s combination of two sets of references, Japanese animation and the spaghetti western, draws attention to the status of revenge as a cross-cultural motif while also demonstrating a key feature of the formula. O-Ren’s insistent questioning as she kills Masumoto: ‘Take a good look at my face. Look at my eyes. Look at my mouth. Do I look familiar? Do I look like somebody … you murdered?!’ parallels Harmonica’s demand for recognition as he looks into Frank’s dying face after their duel. Both films pivot the figure of an innocent child against a psychopathic villain and the absolute distinction between good and evil is crucial to the presentation of exacting revenge as entirely satisfying. However, Harmonica is presented as traumatised by the past, while O-Ren endures a brutal rite of passage into a criminal underworld where she utilises extreme violence to rise to power.

Chapter five, ‘Showdown at the House of Blue Leaves’, builds on and reworks previous intertextual references. The musical cue for the showdown is the theme from the television series

Ironside (NBC, 1967–75) starring Raymond Burr as the eponymous paraplegic Chief of Detectives. It is previously used in chapter one, overlaying Beatrix’s brief flashback to the vipers’ attack in the wedding chapel, which prefaces her fight with Vernita. The repetition of the theme is a narrative recontexualisation – here the allusion to

Ironside underscores Beatrix’s recovery from coma and paralysis. Chapter five also builds on the previous references to spaghetti westerns, adding Morricone’s theme for