4

Metaphysical Dependence, East and West

Ricki Bliss and Graham Priest

Introduction

It is a natural thought that many things have whatever form of being they have because they depend on other things: the shadow depends on the object which casts it, the beauty of a work of art depends on its line and balance, the goodness of a cricket team depends on the goodness of each player, and so on. Although it is often not put in these terms, discussions of metaphysical dependence are common in both Eastern and Western philosophy; and of recent years the topic itself has come in for some intense scrutiny in Western philosophy. However, the Eastern and Western traditions have evolved largely independently of each other. We feel that there can be mutual benefit by bringing them into contact. This is what this chapter aims to do.

In Section 4.3, we will look at some of the ways in which metaphysical dependence occurs in Eastern traditions, and in Section 4.4 we will look at its occurrence in Western traditions. In Section 4.5 we will spell out some of the ways each tradition can benefit by being informed of the other.

Before we do this, however, there is a necessary preliminary. The views on metaphysical dependence are many, and there is a great variety of answers to central questions such as “What sorts of things is it which are dependent or independent?”, “What is the nature of metaphysical dependence?”, and “What is the reality like that metaphysical dependence structures?” To get some order into the chaos we need a framework in which to fit views. We do this by providing a taxonomy, the subject of Section 4.2.

A Taxonomy

Properties of Dependence Relations

How many different kinds of metaphysical dependence relationships there are, and what the connections are between them, are somewhat contentious questions. However, we ignore this point for the moment, and produce a taxonomy by abstracting away from the nature of such dependence relations and focusing on structural features. For those who do not wish to work through the following in detail we give a brief summary at the end of the subsection, which will provide most of what is necessary to understand what follows.

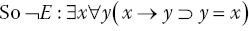

First, some notation. We write “x depends on y” as  .1 (We may write

.1 (We may write  as

as  .) Next, four structural properties.

.) Next, four structural properties.

- Antireflexivity, AR

[Nothing depends on itself.]

[Something depends on itself.]

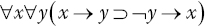

- Antisymmetry, AS

[No things depend on each other.]

[Some things depend on each other.]

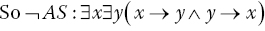

- Transitivity, T

[Everything depends on anything a dependent depends on.]

[Something does not depend on what some dependent depends on.]

- Extendability, E

[Everything depends on something else.]

[Something does not depend on anything else.]

There are certainly other properties of  that we may consider, as we shall see. However, considerations of combinatorial explosion require us to select a relatively small number of conditions to frame the taxonomy. We select AR, AS, and T, since in contemporary discussions these are often taken to be features of metaphysical dependence. We select E since it is fundamental to the issue of whether there is a “fundamental level” of dependence.

that we may consider, as we shall see. However, considerations of combinatorial explosion require us to select a relatively small number of conditions to frame the taxonomy. We select AR, AS, and T, since in contemporary discussions these are often taken to be features of metaphysical dependence. We select E since it is fundamental to the issue of whether there is a “fundamental level” of dependence.

The Taxonomy

We can now give the taxonomy, which is as follows. After the enumeration column, the next four columns list the 16 possibilities of our four conditions. We take up the next two columns in the next subsection.

| AR | AS | T | E | Comments | Special cases | |

| 1 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Infinite partial order | I |

| 2 | Y | Y | Y | N | Partial order | A, F, G |

| 3 | Y | Y | N | Y | Loops | I |

| 4 | Y | Y | N | N | Loops | F, G |

| 5 | Y | N | Y | Y | × | |

| 6 | Y | N | Y | N | × | |

| 7 | Y | N | N | Y | Loops of length >0 | I |

| 8 | Y | N | N | N | Loops of length >0 | F, G |

| 9 | N | Y | Y | Y | × | |

| 10 | N | Y | Y | N | × | |

| 11 | N | Y | N | Y | × | |

| 12 | N | Y | N | N | × | |

| 13 | N | N | Y | Y | Preorder | C, I |

| 14 | N | N | Y | N | Preorder | C, F, F′, G |

| 15 | N | N | N | Y | Loops of any length | I |

| 16 | N | N | N | N | Loops of any length | F, F′, G |

Discussion

Consider, next, the Comments column. Here’s what it means.

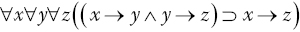

- There is nothing in categories 5 and, 6, since if there are x, y, such that x ⇆ y, then by T,

, contradicting AR. (

, contradicting AR. ( and T imply

and T imply  .)

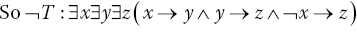

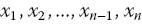

.) - There is nothing in categories 9–12, since if for some x

, then for some x and y, x ⇆ y, contradicting AS. (

, then for some x and y, x ⇆ y, contradicting AS. ( implies

implies  .)

.) - All the other categories are possible, as simple examples (left to the reader) will demonstrate.

- In categories 13–16, since

implies

implies  , the second column (AS) is redundant.

, the second column (AS) is redundant. - In categories 1 and 2,

is a (strict) partial order; and in category 1, the objects involved must be infinite because of E.

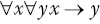

is a (strict) partial order; and in category 1, the objects involved must be infinite because of E. - In categories 13 and 14,

is a (strict) preorder, so loops are possible. (A loop is a collection of elements,

is a (strict) preorder, so loops are possible. (A loop is a collection of elements,  , for some

, for some  , such that

, such that  .)

.) - In categories 3, 4, 7, 8, 15, and 16, transitivity fails, and there can also be loops. In categories 7 and 8, there are no loops of length zero,

, since AR holds.

, since AR holds.

Turning to the final column, this records some important special cases.

- The discrete case is when nothing relates to anything. Call this atomism, A. In this case, we have AR, AS, T,

. So we are in category 2 (though this is not the only thing in category 2).

. So we are in category 2 (though this is not the only thing in category 2). - If

is an equivalence relation (reflexive, symmetric, transitive), we have

is an equivalence relation (reflexive, symmetric, transitive), we have  ,

,  , T, so we are in categories 13 or 14 (though this is not the only thing in these two categories). In category 13, there must be more than one thing in each equivalence class, because of E. A limit case of this is when all things relate to each other:

, T, so we are in categories 13 or 14 (though this is not the only thing in these two categories). In category 13, there must be more than one thing in each equivalence class, because of E. A limit case of this is when all things relate to each other:  . Call this coherentism, C.

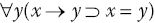

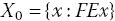

. Call this coherentism, C. - Call x a foundational element (FEx) if there is no y on which x depends, except perhaps itself:

. Foundationalism, F, is the view that everything grounds out in foundational elements. One way to cash out the idea is as follows.2 Let

. Foundationalism, F, is the view that everything grounds out in foundational elements. One way to cash out the idea is as follows.2 Let  , and for any natural number,

, and for any natural number,  :

:  iff

iff  or

or  ).

).  . F is the view that everything is in X,

. F is the view that everything is in X,  .3 Intuitively, this means that everything is a foundational element, or depends on just the foundational elements, or depends on just those and the foundational elements, and so on. E entails that there are no foundational elements. Hence, this is incompatible with F. So, given F, we must be in an even‐numbered case – except those that are already ruled out by other considerations. (All are possible. Merely consider

.3 Intuitively, this means that everything is a foundational element, or depends on just the foundational elements, or depends on just those and the foundational elements, and so on. E entails that there are no foundational elements. Hence, this is incompatible with F. So, given F, we must be in an even‐numbered case – except those that are already ruled out by other considerations. (All are possible. Merely consider  . z is foundational; add in arrows as required to deliver the other conditions.)

. z is foundational; add in arrows as required to deliver the other conditions.) - A special case of foundationalism is when the foundational objects, and only those, depend on themselves:

. Call this view F′. Since AR must fail in this case, we must be in categories 14 or 16 of the taxonomy.

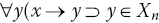

. Call this view F′. Since AR must fail in this case, we must be in categories 14 or 16 of the taxonomy. - Another special case of foundationalism is when there is a unique foundational object on which everything else depends:

. [Something is a foundational element, and everything else depends on it.] The x in question does not depend on anything, except perhaps itself, and it must be unique, or it would depend on something else. Call this case G (since the x could be a God which depends on nothing, or only itself). This is a special case of F, and could be in any of the cases in which F holds.

. [Something is a foundational element, and everything else depends on it.] The x in question does not depend on anything, except perhaps itself, and it must be unique, or it would depend on something else. Call this case G (since the x could be a God which depends on nothing, or only itself). This is a special case of F, and could be in any of the cases in which F holds. - Write

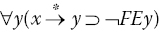

to mean that y is in the transitive closure of

to mean that y is in the transitive closure of  from x. That is, one can get from x to y by going down a finite sequence of arrows. An element, x, is ultimately ungrounded, UGx, if, going down a sequence of arrows, one never comes to a foundational element:

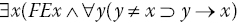

from x. That is, one can get from x to y by going down a finite sequence of arrows. An element, x, is ultimately ungrounded, UGx, if, going down a sequence of arrows, one never comes to a foundational element:  . Infinitism, I, is the view that every element is ultimately ungrounded:

. Infinitism, I, is the view that every element is ultimately ungrounded:  .4 We note that infinitism allows for the possibility of loops, that is, repetitions in the regress. Thus, we have the following possibility:

.4 We note that infinitism allows for the possibility of loops, that is, repetitions in the regress. Thus, we have the following possibility:  However, if

However, if  is transitive and antisymmetric (T and AS), such loops are ruled out. Infinitism entails extendability, E. So if I holds we must be in an odd‐numbered category of our taxonomy (which is not ruled out by other considerations). All such are possible, as simple examples demonstrate. (Merely consider

is transitive and antisymmetric (T and AS), such loops are ruled out. Infinitism entails extendability, E. So if I holds we must be in an odd‐numbered category of our taxonomy (which is not ruled out by other considerations). All such are possible, as simple examples demonstrate. (Merely consider  , where these are all distinct. Add in other arrows as required.) Note that if there are at least two elements, then C is a special case of I.

, where these are all distinct. Add in other arrows as required.) Note that if there are at least two elements, then C is a special case of I. - A final special case. Let x ⇄ y iff

. Then x and y are connected along the dependence relation, xCy, iff for some

. Then x and y are connected along the dependence relation, xCy, iff for some  :[Everything relates to everything else along some sequence of dependence relations.]

:[Everything relates to everything else along some sequence of dependence relations.]

itself is connected iff

itself is connected iff  . In all of the ten possible cases,

. In all of the ten possible cases,  may be connected or not connected. G is a special case of connectedness; C is an extreme case of connectedness; and A is an extreme case of disconnectedness.

may be connected or not connected. G is a special case of connectedness; C is an extreme case of connectedness; and A is an extreme case of disconnectedness.

Let us finish this section with an informal summary. The taxonomy is built on four conditions: (i) antireflexivity, AR: nothing depends on itself; (ii) antisymmetry, AS: no things depend on each other; (iii) transitivity, T: everything depends on whatever a dependent depends on; and (iv) extendability, E: everything depends on something else. This gives us 16 ( ) possibilities. Six of these are ruled out by logical considerations, leaving ten live possibilities. Within these, some special cases may be noted: atomism, A: nothing depends on anything; foundationalism, F: everything is a fundamental element or depends, ultimately, on such; F′: foundationalism, where the fundamental elements and only those depend on themselves; G: foundationalism where the fundamental element is unique; infinitism, I: there are no fundamental elements; coherentism, C: everything depends on everything else.

) possibilities. Six of these are ruled out by logical considerations, leaving ten live possibilities. Within these, some special cases may be noted: atomism, A: nothing depends on anything; foundationalism, F: everything is a fundamental element or depends, ultimately, on such; F′: foundationalism, where the fundamental elements and only those depend on themselves; G: foundationalism where the fundamental element is unique; infinitism, I: there are no fundamental elements; coherentism, C: everything depends on everything else.

Metaphysical Dependence in the Buddhist Traditions

Orientation

We will now turn to discussions of metaphysical dependence in Eastern traditions, specifically the Buddhist tradition. We do not wish to suggest that there are no interesting discussions to be found in other Eastern traditions, such as Vedic and Daoist traditions; but only so much can be done in one article, and the Buddhist tradition is the one we know best. (We would encourage those who know more about these other traditions to engage in the discussions.) Moreover, the Buddhist tradition, itself, is not homogeneous, as we shall see. We will talk of three parts of it. Again, we do not wish to suggest there are no interesting elements in other parts of the tradition; we choose the three we do because they provide particularly interesting and contrasting views concerning metaphysical dependence.

For those unfamiliar with Buddhist philosophy, let us start with a brief description of its historical development. Buddhist thought started with the historical Buddha, Siddhārtha Gautama. His dates are uncertain, but he flourished around 450 BCE, and his ideas were developed in a canonical way for the next 500 years or so. The philosophical part of this development was called Abhidharma (higher teachings). There were many Abhidharma schools. The only one to survive to this day is Theravāda (Way of the Elders).

Around the turn of the Common Era, novel ideas emerged which were critical of the older tradition. This generated a new kind of Buddhism: Mahāyāna. The foundational philosopher of this kind of Buddhism was Nāgārjuna. Dates are, again, uncertain, but he flourished around 200 CE. He founded the version of Mahāyāna Buddhism called Madhyamaka (Middle Way).

Buddhist thought died out in India around the twelfth century, but by that time it had spread to the rest of Asia, Theravada going south‐east, and Mahāyāna going north‐west into central Asia, and thence across the Silk Route into East Asia. It entered China around the turn of the Common Era, where it met the indigenous philosophical traditions Confucianism and Daoism. Daoism, in particular, exerted a crucial influence on Buddhist thought.5 This resulted in the emergence of distinctively Chinese forms of Mahāyāna Buddhism, around the sixth century. Some of these, such as Chan (Jp. Zen) are still extant. But perhaps the most philosophically sophisticated of these flourished in China for only a few hundred years (though it still has a presence in Korea and Japan). This was Huayan (Skt Avataṃsaka; K. Hwaeom; Jp. Kegon; Eng. Flower Garland) Buddhism, named after the sūtra it took to be most important. Many Huayan ideas were incorporated into other forms of Buddhism (and indeed into Neo‐Confucianism). The most influential philosopher in this tradition was Fazang, traditionally dated as 643–712.6

With this background, let us turn to our three views concerning ontological dependence: those of Abhidharma, Madhyamaka, and Huayan.

Well‐Founded Buddhism

It is common to all types of Buddhism that the world of our common experience is a world of dependent origination, pratītyasamutpāda. Nothing is permanent: things come into existence when causes and conditions are ripe, and go out of existence in the same way. Now, how should one think of a person in this context?

The understanding of a person that developed in the Abhidharma literature was as follows. Consider a car.7 This comes into existence when its parts are put together. The parts interact with each other and the environment; they wear out and are replaced; and they finally fall apart entirely. Persons are just like that. True, their parts (skandhas), unlike the car’s, are both physical (rūpa) and mental. But otherwise the story is the same. Of course we can think of this dynamically evolving bunch of parts as a single thing, a person; we can even give it a name, say “Bertrand Russell”; but this is just a matter of convenience.

The Abhidharma philosophers could see nothing special about people in this way. Anything with parts, like our friend the car, is exactly the same. Indeed, what anything in our common world of experience is, depends on what its parts are and how we think about them.

So take the car again. This depends on its wheels, engine, chassis, and so on. The engine depends on its combustion chambers, fuel‐injection system, and so on. If we keep deconstructing in this way, do we come to things where no further deconstruction is possible? The Abhidharma philosophers thought that the answer was obviously “yes.” If something is a conceptual construction, there must be something, dharmas, out of which it is constructed. You can’t make something out of nothing. This would seem to be the point when Asaṅga (fl. ca. fourth century CE), in a late Abhidharma text, says:

Denying the mere thing with respect to dharmas such as rūpa and the like, neither reality nor conceptual fiction is possible. For instance, where there are the skandhas of rūpa etc., there is the conceptual fiction of the person. And where they are not, the conceptual fiction of the person is unreal. Likewise if there is a mere thing with respect to dharmas like rūpa etc., then the use of convenient designators concerning dharmas such as rūpa and the like is appropriate. If not then the use of convenient designators is unreal. Where the thing referred to by the concept does not exist, the groundless conceptual fiction likewise does not exist.8

There was some dispute about the nature of the dharmas (a common view was that they are tropes of some kind). But, as all agreed, they are just as impermanent as anything else; what distinguishes them is the fact that they are what they are independently of anything else (parts, concepts, each other). They have svabhāva (self‐being).9

The Abhidharma philosophers described the picture as one of two realities.10 There is the fundamental reality composed of dharmas – ultimate reality (paramārtha‐satya); then there is the conceptual reality constructed out of this – conventional reality (saṃvṛti‐satya).

Clearly, the whole picture paints a story concerning metaphysical dependence. Where does it lie in our taxonomy of Section 4.2.2? It is obviously some kind of foundationalism, where Fx is “x is a dharma.” Does it endorse AR, AS, and T? We know of no explicit discussion of these matters in the texts, but let us extrapolate. The Abhidharma philosophers would probably have endorsed transitivity. If the car depends on its engine, and the engine depends on its fuel‐injector, the car depends on its fuel‐injector. Moreover, a whole would appear to depend on its parts, in a way that the parts do not depend on the whole.11 So the dependence relation would seem to be antisymmetric. Since antisymmetry entails antireflexivity, we have that as well. So this puts us in category 2 of the taxonomy.

Non‐Well‐Founded Buddhism

We now turn to Madhyamaka. Madhyamaka entirely rejected the notion of the dharmas. Nothing has svabhāva. Everything is what it is by relating to other things. The Madhyamaka philosophers accepted the Abhidharma view that the relations in question could be mereological and conceptual, but also added an important third dimension: causal (e.g., a person is what they are because of their relations to their parents, their genetic structure, etc.). Everything depends on other things in some or all of these ways. That is, all things are empty (śūnya) of self‐being.12

In much of his enormously influential text the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (MMK, Fundamental Verses of the Middle Way) Nāgārjuna mounts the case that nothing has svabhāva.13 He does this by running through all the things one might suppose to have it (causation, consciousness, space, etc.), and rejecting each one. Many of the arguments are reductio ones. We assume that something has svabhāva and show that this cannot be.14 We will not consider the arguments in any detail here.

More to the point in this context, one might expect Nāgārjuna to have rejected the distinction between the two realities. But he does not (MMK XXIV.8–10):

The Buddha’s teaching of the Dharma

Is based on two truths:

A truth of worldly convention

And an ultimate truth.

Those who do not understand

The distinction between these two truths

Do not understand

The Buddha’s profound truth.15

Conventional reality is the world of our familiar experience. But if there are no things with svabhāva, what is ultimate reality?

Though hardly explicit in the MMK, the view that emerged in Madhyamaka was that ultimate reality is what is left if one takes the things of conventional reality and strips off all conceptual overlays: emptiness (Skt śūnyatā; Ch. kong) itself. One might well think that this ultimate reality provides some foundational bedrock.16 It does not. According to Madhyamaka, everything is empty, including emptiness itself. In perhaps the most famous verse of the MMK (XXIV.18), Nāgārjuna says:

Whatever is dependently co‐arisen

That is explained to be emptiness.

That, being a dependent designation,

Is itself the middle way.

Emptiness, as the verse says, is a dependent designation. That is, emptiness depends on something. Conventional reality clearly depends on ultimate reality. But what does ultimate reality depend on? It is hard to extract a clear answer to this question from the MMK; let us set it aside for the moment.

We are now in a position to see how the Madhyamaka view fits into our taxonomy. In general it takes over the Abhidharma view, but simply rejects its foundationalism. That is, it endorses E. We have infinitism, I, and we are in category 1.

Buddhist Coherentism

Let us now turn to Huayan.17 This, like all Chinese Buddhisms, is Mahāyāna, and so inherited Madhyamaka thought. But whilst Madhyamaka held that all things depend on some other things, the Huayan universalized: all things depend on all other things. How did they get there? We come back to the question of what ultimate reality depends on.18

As we have noted, Chinese Buddhism was indebted to Daoism. According to a standard interpretation of this, behind the flux of phenomenal events there is a fundamental principle, dao, which manifests itself in the flux. To Chinese Buddhist eyes, it was all too natural to identify the flux with conventional reality, and the dao with ultimate reality. That is exactly what happened. Moreover, just as one cannot have manifestations without whatever it is of which they are a manifestation, one cannot have something whose nature it is to manifest, without the manifestations. So conventional reality depends on ultimate reality, and ultimate reality depends on conventional reality: they are two sides of the same coin. In his Treatise on the Golden Lion, Fazang explains the point in this way. Imagine a statue of a golden lion. The gold is like ultimate reality; the shape is like conventional reality. One cannot have the one without the other.

By this time in the development of Buddhist thought, the objects of phenomenal reality are called shi and ultimate reality is referred to as li, principle. Hence we have the Huayan principle of the mutual dependence of li and shi: lishi wuai. The matter is put this way by the Huayan thinker Dushun (557–640):

Shi, the matter that embraces, has boundaries and limitations, and li, the truth that is embraced [by things], has no boundaries or limitations. Yet this limited shi is completely identical, not partially identical, with li. Why? Because shi has no substance [svabhāva] – it is the selfsame li. Therefore, without causing the slightest damage to itself, an atom can embrace the whole universe. If one atom is so, all other dharmas should also be so. Contemplate on this.19

But if every shi depends on li, then by the transitivity of dependence, every shi depends on every other shi. Hence we have the Huayan thesis of the dependence (interpenetration) of every shi on every other shi: shishi wuai. Chengguan (738–839?), another Huayan thinker, puts the matter thus:

Because they have no self‐being [svabhāva], the large and the small can mutually contain each other… Since the very small is very large Mount Sumeru is contained in a mustard seed; and since the very large is the very small, the ocean is included in a hair.20

We therefore arrive at this: all things, whether li or shi, depend on each other.

The situation is depicted in what is arguably the most famous image in Huayan: the Net of Indra. A god has spread out a net through space. At each node of the net there is a brightly polished jewel. Each jewel reflects each other jewel, reflecting each other jewel, reflecting… to infinity. Fazang puts the metaphor thus:

It is like the net of Indra which is entirely made up of jewels. Due to their brightness and transparency, they reflect each other. In each of the jewels, the images of all the other jewels are [completely] reflected… Thus, the images multiply infinitely, and all these multiple infinite images are bright and clear inside this single jewel.21

Each jewel represents an object. And it is the nature of each jewel to encode every other jewel, including that jewel encoding every other jewel, and so on.

So where is the Huayan picture in our taxonomy? Clearly, this is coherentism, C, and we are in category 13 (since there is more than one object).

Metaphysical Dependence in Western Traditions

The General Picture

Now let us turn to discussions of metaphysical dependence in the Western traditions. In contrast to the Eastern literature, two aspects are immediately striking. The first is that, unlike in the Eastern traditions, there is an absolute orthodoxy on how reality is structured: some kind of foundationalism.22 The second is that the contemporary period, at least, in the West has seen concerted attempts to theorize about the dependence relation itself – in terms both of its nature and its structure. Discussions of metaphysical dependence in the West are, then, richer than those in the East in one sense, and poorer in another. We will see both of these in what follows. But, again, first some general background.

The idea that reality has a particular kind of structure is as old as the Western tradition itself. An example of this is the great chain of being of the Neo‐Platonists.23 First and foremost, there is the One, or God, who grounds successive layers of reality – hypostates – in a hierarchy of dependence.

Whilst it is certainly not the case that the Western literature is a long history of philosophers speaking in the idioms of metaphysical dependence, the ideas that, on the one hand, reality is hierarchically structured, and, on the other, there is something fundamental have cast a very long shadow over the tradition.24

In the footsteps of the ancient Greeks, the Medievals and the Moderns were also concerned with what was independent – substances and God, commonly – and the dependence ordering in relation to them. The works of Aquinas, Scotus, Kant, and Leibniz, amongst many others, are, in places at least, wholly focused upon arguing for a distinctively foundationalist picture. Empiricists such as Hume arguably also have foundationalist leanings, with the atomisms of Russell, Wittgenstein and, more recently, Armstrong continuing the tradition.

In Sections 4.4.2 and 4.4.3 we review some material from the history of Western philosophy. As it is clearly impossible to do justice to the whole of it here, we select two important figures: Aristotle and Leibniz. Indeed, we can hardly hope to do justice to the richness of their thoughts either, but we hope we can say enough to indicate the general lay of the land. In Sections 4.4.4 and 4.4.5 we turn to a consideration of some of the contemporary proponents of foundationalism and their reasons for holding the view, along with some reasons for rejecting it.

We end these preliminary comments by noting that there is a distinction drawn in the contemporary literature between two kinds of metaphysical dependence: ontological dependence and grounding. What exactly these are, and the relationship between them, are contentious matters; indeed, the terminology is not itself well defined.25 However, a few points can be stated with a relative degree of confidence. First, grounding is generally taken to be a relation between facts,26 whereas ontological dependence can obtain between relata of all ontological categories. Next, many hold that there is some kind of necessity involved in a relationship of metaphysical dependence. If so, it is often taken to run in different directions in the two cases. Where A ontologically depends on B, A necessitates B, whereas if A is grounded in B, B necessitates A. Finally, ontological dependence might involve explanatory connections, whereas grounding always does.

Some Historical Views I: Aristotle

So to Aristotle. It has become something of a common – if mistaken – assumption that Aristotle was not particularly concerned with what exists. Instead, it is said, Aristotle was concerned with what depends on what.27 He was, indeed, very much concerned with a particular kind of dependence ordering in nature.

To discuss dependence in Aristotle we must first begin by introducing some basic features of his account, and we choose here to focus upon the account offered in the Categories.28 For Aristotle, the categories of existents include substance, quantity, quality, and relation, with each category containing both individuals and universals. This means that we can distinguish individual substances from both universal substances and, say, individual relations, for example. An example of an individual substance for the Aristotle of the Categories is a horse; and an example of a universal substance is HUMAN. COLOR, on the other hand, is an example of a quality, a non‐substance. Henceforth, we refer to everything that is neither an individual nor a universal substance as a non‐substance.

One of Aristotle’s great concerns in the Categories is securing a certain ontological status for the individual substances. The distinction between individual substances and everything else is drawn by him in terms of a distinction between being in and being said of something else: individual substances are that of which things are said, or in which things are. What this means is that the subjects of predications are individual substances with predicates being in, or said of, them. So, for example, to say that Sam is human is to say of an individual substance, Sam, that he is human. Color, on the other hand, we say is in Sam.

On the relationship between individual substances (primary substances) and universal substances (secondary substances), Aristotle says:

A substance – that which is called a substance most strictly, primarily, and most of all – is that which is neither said of a subject nor in a subject, e.g. the individual man or the individual horse. The species in which the things primarily called substances are, are called secondary substances, as also are the genera of those species. For example, the individual man belongs in a species, man, and animal is a genus of the species; so these – both man and animal – are called secondary substances.29

The use of the expressions “primary” and “secondary” should give us our first clue as to what Aristotle is up to, for they convey the idea of one thing’s being more or less basic in an ordering than another. Metaphysical dependence is widely thought to be framed in the language of separation and priority in Aristotle.30 One thing is metaphysically dependent on something else just in case it is not separate from that thing; where that something else is prior to it. For Aristotle, non‐substances and universal substances are inseparable from that in which they are, or that of which they are said; where individual substances are said to be prior. Importantly, on the Aristotelian picture, the individual substances are that which, and only that which, are separate from all else: so only they can be without the non‐substances.31 The primary substances are said to play a particularly important role:

All the other things are either said of the primary [i.e. individual] substances as subjects or present in them as subjects… [C]olor is present in body and therefore also present in an individual body; for were it not present in some individual body it would not be present in body at all… So if the primary substances did not exist it would be impossible for any of the other things to exist.32

But what are we to make of all this talk of separability, priority, and substance? It seems very natural to understand them in terms of some kind of metaphysical dependence. What we might understand Aristotle as saying, then, is that where A is prior to and separate from B, B depends on A, in the sense of being metaphysically explained by it.33 Consider universal substances, for example, HUMAN. These appear to have their being in virtue of being said of individual substances. There would be no universal substance HUMAN were there no humans at all. So universal substances are posterior to and not separable from individual substances because they have their being explained in terms of them. However, individual substances do not appear to have anything in virtue of which they have their being explained. So individual substances are prior and separate because there is nothing in virtue of which they have their being.34

So where in our taxonomy should we place Aristotle? It seems clear that Aristotle was at pains to establish a priority ordering in which dependence was not symmetric, so we can take him as embracing AS. As Aristotle assumes that without the primary substances nothing else would exist, he seems to be committed to T. For this same reason, it seems safe to say that he denied E. This would put Aristotle firmly in category 2. As Aristotle is often cited as the grandfather of the foundationalist view that currently dominates Western traditions, this hardly comes as a surprise.

Some Historical Views II: Leibniz

Next, we turn to some aspects of Leibniz’ thought relating to metaphysical dependence. What is striking here is that although Leibniz’ picture of the world offers a radical departure from the standard view at the time, the picture presented is nonetheless a thoroughgoing foundationalism. Again, we can hardly do justice to all aspects of his thought, and we choose to focus on the grounding of modal facts as a special case of the grounding of everything in God. Although Leibniz certainly believed that everything within the created world was dependent upon the monads, we do not venture into the thorny issue of how the monads fit into Leibniz’ big picture.35

The idea that everything depends on God is a cornerstone of Leibniz’ thought (and, of course, of theistic philosophy in general). But what exactly does it mean? Is it enough that God exists to explain everything else, or is there something that God needs to do beyond merely existing to explain the world? As we will see, for Leibniz, God’s mere existence is necessary to explain the existence of everything else, but it is not sufficient: God’s intellect forms a crucial part of the story.

Let us first consider Leibniz’ cosmological argument for the existence of God. In the Monadology, Leibniz states:

[B]ut all this detail only brings in other contingencies…and each of these further contingencies also needs to be explained through a similar analysis. So when we give explanations of this sort we move no nearer to the goal of completely explaining contingencies. Infinite though it may be, the train of detailed facts about contingencies…doesn’t contain the sufficient reason, the ultimate reason for any contingent fact. For that we must look outside the sequence of contingencies.36

Invoking contingencies to explain contingencies leaves us in the unfortunate position, thinks Leibniz, of not having completely explained the contingencies at all. If what we want is a complete explanation of the contingencies – as Leibniz thinks we do – then we need something beyond the collection of contingent things in order to do that: what is needed to explain the existence of the contingent things is a necessary being. And this necessary being, thinks Leibniz, is God.

There is much that can be said about this argument, but for our purposes what is interesting is that, unlike many of the other arguments in the literature, this one makes appeal to a distinctive kind of metaphysical explanation. Leibniz is not concerned with efficient causation: he is not worried that if there were no first cause in time, nothing would exist whatsoever, for example. Instead, Leibniz is concerned with how the world can be fully accounted for – what sufficient reason we can uncover for its existence.

The story of how God explains the world is much more complex than this, however. After all, if it’s simply that we need a necessary being in order to explain the contingencies, there are plenty more mundane necessities around that would be available for the task.

Amongst the set of truths to be explained by God are the modal truths: truths such as that  is necessarily 4, and that Leibniz could have traveled to Kyoto. Let us narrow our focus to these for a moment. How might such truths depend on God? In broad strokes, according to Leibniz, modal truths express facts about essences which, in turn, are grounded in God’s intellect. The grounding of modal truths, then, is the story of how essences depend on the mind of God.37

is necessarily 4, and that Leibniz could have traveled to Kyoto. Let us narrow our focus to these for a moment. How might such truths depend on God? In broad strokes, according to Leibniz, modal truths express facts about essences which, in turn, are grounded in God’s intellect. The grounding of modal truths, then, is the story of how essences depend on the mind of God.37

But what kind of relation does God bear to all these essences for Leibniz? Does God thinking about the nature of something cause that nature to exist? No. God’s ruminations on essences are to those essences as substances are to modes.38 It is not that my apple causes its redness to exist but, rather, that my apple qua substance grounds its redness qua mode. The apple is ontologically prior to its redness, just as the redness depends on the apple. So too for essences and their dependence on the mind of God. Being thought of by God lends reality to and grounds the existence of essences.

So where in our taxonomy might we place Leibniz? Leibniz was certainly a foundationalist, which has him in categories 2, 4, 8, 14, or 16. As everything for Leibniz depended ultimately on God, we can assume that he accepted T. This rules out categories 4, 8, and 16. Leibniz denied, though, that dependence was antireflexive: God, for Leibniz, depended on Himself. This leaves us, then, in category 14 and with Leibniz, according to our characterization, endorsing G.

Contemporary Orthodoxy

We now turn to contemporary Western discussions of metaphysical dependence. First, we discuss the dominant contemporary picture. Then we consider some of the contemporary challenges that have been made to it, and relate these back to our taxonomy of possible positions. In the process we will see, as promised, how dependence itself has become an object of philosophical scrutiny.

Although contemporary philosophers tend not to concern themselves with the existence of God, and our understanding of the natural world has evolved considerably, without question the prevailing view amongst contemporary metaphysicians is that reality is hierarchically structured with chains of entities ordered by ontological dependence relations that terminate in something fundamental. This is obviously a species of metaphysical foundationalism, and it is not, in many important, abstract senses, a wildly different view of reality than that which has held sway for thousands of years in the West.

A quick look at our taxonomy reveals, however, that there are five different ways in which one can be a foundationalist. Is one of these views more common than the others? As the reader may have guessed, it most certainly is, and that is category 2: AR, AS, T, and  . But why? Why suppose that reality is hierarchically arranged by metaphysical dependence relations that are antisymmetric, antireflexive, and transitive, where those dependence chains terminate in something fundamental? Let us first consider the idea that our relations induce a partial order.

. But why? Why suppose that reality is hierarchically arranged by metaphysical dependence relations that are antisymmetric, antireflexive, and transitive, where those dependence chains terminate in something fundamental? Let us first consider the idea that our relations induce a partial order.

One quick justification for committing to the view is that it just seems plain obvious. Take the flagpole and its shadow. Common sense tells us that the shadow depends on the flagpole in a way that the flagpole does not depend on its shadow (antisymmetry). Similarly it seems right to suppose that where I depend on my vital organs and they on their cellular components, I also depend on those cellular components (transitivity).39 And the idea that anything depends on itself, some say, is plain ridiculous (antireflexivity).40

Why suppose there must be something fundamental? There is a host of sometimes not very well‐articulated arguments. Kit Fine considers that it is at least a plausible demand on the ground that chains ordered by the relation yield “completely satisfactory” explanations.41 Ross Cameron thinks that a theory that posits fundamentalia is ceteris paribus better than one that does not.42

Perhaps the most compelling argument available in defense of fundamentalia, however, is one from vicious infinite regress. According to such an argument, where one thing depends upon something else and that thing upon still something else, and so on ad infinitum, nothing within the chain has any being or reality whatsoever. As Jonathan Schaffer puts it: if there is nothing fundamental, being would be “infinitely deferred, never achieved.”43

Challenges to Contemporary Orthodoxy

Although category 2 of our taxonomy is the standard orthodoxy, it has not gone without challenge. Consider, first, the idea that we might accept extendability, and therewith reject the idea that there is something fundamental. A reality in which there is nothing fundamental would be a reality in which there are infinitely descending dependence chains: there is no fundamental level (infinitism). Both Tahko (2014) and Morganti (2014) have defended the possibility of species of infinitism. Other authors (e.g., Paseau 2010) have suggested it is at least advisable to remain neutral as to whether there is anything fundamental.

What would be so bad about such a picture, if anything at all, is more difficult to establish than commonly realized.44 One thought might be that there would just be too much stuff – a violation of quantitative parsimony. But this doesn’t seem like a legitimate worry: not only is parsimony normally understood qualitatively and not quantitatively, but the foundationalist is generally happy to admit that there may be an infinite number of fundamentalia.45

The worry might be that there is something special about our dependence chains that means that it is necessary that they terminate downwards. It might seem obvious that where our explanatory chains do not terminate, we don’t really have complete explanations of everything we have encountered along the way. Whatever the intuitive pull of this concern, it is very difficult to formulate it in a way that would actually allow us to motivate foundationalism. On the face of it, this concern just looks like the demand that we terminate our explanatory chains. As explanatory chains are not defective simply by dint of being incomplete, it is not entirely clear what the problem is supposed to be. Is there perhaps some appeal to an appropriate version of the Principle of Sufficient Reason?46 A closer examination of the arguments reveals that not much at all may be lost if we abandon our commitment to fundamentality.

Let us now turn to a consideration of the possibility of reflexive instances of dependence. Why suppose that ontological dependence relations are necessarily antireflexive? One way to respond to this question is with “They’re not!” Some philosophers consider that there is no in principle problem with the thought that ontological dependence can be reflexive.47 In fact, Jenkins has even argued that there appear to be instances of dependence that are reflexive.48 Many philosophers, however, are of the view that grounding cannot be reflexive. This seems to be due to the intimate connection between grounding and explanation: reflexive explanations are trivial and uninformative.

Similar reasoning would appear to be in operation in defense of the view that dependence is necessarily antisymmetric: symmetric explanations are epistemically undesirable. But what, if any, might be the metaphysical reasons to suppose that ontological dependence relations must be antisymmetric? One thought might be that where A depends on B and B depends on A, whilst we can account for A, and we can account for B, we haven’t really accounted for how A and B came to be in the first place. This worry, we suppose, is also what might drive the thought that loops of any size would be unacceptable. How to respond to such an objection might begin by noting that such explanatory loops are not altogether bereft of explanation – after all, we’ve explained both A and B. What we haven’t explained, though, is how the whole lot got going in the first place. But note that this is a different issue, and there are at least two ways that we can respond to it. The first involves claiming that the loop itself just doesn’t need an explanation. The second involves embedding the loop in a larger structure: what explains the fact that A grounds B and B grounds A is some further fact, C.

Some authors have also suggested that there are relatively clear‐cut cases of failures of transitivity. Consider the following. It seems reasonable to suppose that the fact that a ball has a dent in it grounds the fact that it has a certain shape, S. It also seems reasonable to suppose that the fact that that thing has shape S grounds the fact that it is more or less spherical. What does not seem acceptable, however, is the claim that the fact that some thing has a dent in it grounds the fact that it is more or less spherical.49 We appear to have a failure of transitivity.

Let us end this discussion by locating some of the unorthodox contemporary positions mooted or espoused with respect to our taxonomy as given in the table in Section 4.2.2. Let us begin by considering the view at line 1. We can think of this as a kind of metaphysical infinitism. It is like the standard view in the sense that reality retains its hierarchical structure, but unlike the standard view in that it denies that there is anything fundamental. Bliss (2013), Bohn (2009), Morganti (2014), Tahko (2014), and Schaffer (2003) (before he changed his mind) have all defended the possibility of this view. The views at both lines 3 and 4 are unique in that they allow the possibility of loops in which chains of phenomena ordered by an antireflexive, antisymmetric relation double back on themselves. Fine (1994) has expressed that the view at line 4 is at least a possibility.

Elizabeth Barnes (forthcoming) has argued that we have good reasons to question the dogged commitment to antisymmetry. Line 8, then, is also occupied. And the possibility of line 7 has been defended by Bliss (2012). Priest (2014, chs. 11 and 12) has defended the view that ontological dependence relations are reflexive, symmetric, and non‐well‐founded: a radical kind of metaphysical coherentism. So line 13 also has an occupant. And both Dasgupta (2014) and Lowe (2012) believe that whatever serve as our fundamentalia can be and are, respectively, self‐dependent, so line 14 also has takers. And the possibility of lines 15 and 16 has also been defended by Bliss (2012).

The Fruits of Dialogue

As we have seen, the literatures of the East and West involving ontological dependence and grounding look quite different. We believe that when brought into contact, these two literatures can mutually benefit one another and extract some of the possible fruits below.

First, Western traditions have been largely foundationalist and contain important arguments for foundationalism, whilst Buddhist traditions have been largely anti‐foundationalist and have no well‐developed arguments for this view. The Eastern anti‐foundationalist positions need to take the arguments from the Western traditions into account.

Second, an understanding of the view that there are major philosophical traditions that are not foundationalist can remove the myopia of the Western foundationalist view. Moreover, the Buddhist views are a rich source of anti‐foundationalist arguments, which Western views need to take into account.

Third, recent discussions of dependence in the West have cast a critical eye on the nature of dependence as such. What sorts of thing are they which are so related: objects? properties? facts? Or can all such things enter into dependence relations? Does this mean that there is more than one kind of dependence relation? And what are the structural properties of the dependence relation or relations? Is it (are they) transitive, antisymmetric, antireflexive? And what exactly is the connection, if there is one, between dependence and modal notions, or dependence and explanation?50 Debates in the West may certainly be inconclusive at the moment; but never mind. A closer philosophical scrutiny of dependence as such can only deepen an understanding of notions of dependence in the Buddhist tradition, making them more sophisticated.

Conversely, of course, the sorts of dependence relations present in the Buddhist traditions can only help to hone our understanding of dependence in general.

Much is therefore to be gained on both sides.

Conclusion

In this chapter we have looked at the relation (or relations) of metaphysical dependence as they feature in philosophy – both historical and contemporary. In an essay of this nature we have been able to do little more than sketch briefly some of the terrain; neither have we attempted to resolve any substantial philosophical issues. Our main aim has been to show that the notion of metaphysical dependence is an important feature of both Western and Eastern traditions, and to alert philosophers who are aware of only one side of this divide to the existence of the other. If it serves to bring the two traditions into dialogue, and so advance this central area of metaphysics, we will feel it has achieved its goal.51

References

- Ackrill, J.L., trans. 1963. Aristotle’s Categories and De Interpretatione. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Barnes, E. (forthcoming). “Symmetric Dependence.” In Reality and Its Structure, edited by Ricki Bliss and Graham Priest. Oxford University Press. http://elizabethbarnesphilosophy.weebly.com/uploads/3/8/1/0/38105685/symmetric_dependence.pdf

- Barnes, J., ed. 1984. The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Bennett, J., trans. 2007. The Principles of Philosophy Known as Monadology. www.earlymoderntexts.com

- Bliss, R.L. 2012. Against Metaphysical Foundationalism. Doctoral dissertation, University of Melbourne.

- Bliss, R.L. 2013. “Viciousness and the Structure of Reality.” Philosophical Studies 166: 399–418.

- Bliss, R.L. and Trogdon, K. 2014. “Metaphysical Grounding.” In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by E. Zalta. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/grounding/

- Bohn, E.D. 2009. “Must There be a Top Level?” The Philosophical Quarterly 59: 193–201.

- Cameron, R. 2008. “Turtles All the Way Down: Regress, Priority and Fundamentality.” The Philosophical Quarterly 58: 1–14.

- Chang, G.C.C. 1972. The Buddhist Teaching of Totality: The Philosophy of Hwa Yen Buddhism. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- Corkum, P. 2013. “Substance and Independence in Aristotle.” In Varieties of Dependence: Ontological Dependence, Supervenience, and Response‐Dependence, edited by B. Schnieder, A. Steinberg, and M. Hoeltje, 65–96. Basic Philosophical Concepts Series. Munich: Philosophia Verlag.

- Corkum, P. 2016. “Ontological Dependence and Grounding in Aristotle.” Oxford Handbooks Online – Philosophy. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935314.013.31

- Dasgupta, S. 2014. “Metaphysical Rationalism.” Noûs 48: 1–40.

- Dixon, T.S. 2016. “What is the Well‐Foundedness of Grounding?” Mind 125(498): 439–468.

- Fine, K. 1994. “Essence and Modality.” Philosophical Perspectives 8: 1–16.

- Fine, K. 2010. “Some Puzzles of Ground.” Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic 51: 97–118.

- Garfield, J. 1995. The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Jenkins, C.S. 2011. “Is Metaphysical Dependence Irreflexive?” The Monist 94: 267–276.

- Levey, S. 2007. “On Unity and Simple Substance in Leibniz.” The Leibniz Review 17: 61–106.

- Liu, M.W. 1982. “The Harmonious Universe of Fazang and Leibniz.” Philosophy East and West 32: 61–76.

- Lovejoy, A.O. 1936. The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Lowe, E.J. 2012. “Asymmetrical Dependence Individuation.” In Metaphysical Grounding: Understanding the Structure of Reality, edited by F. Correia and B. Schnieder, 214–233. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mitchell, D. 2002. Buddhism: Introducing the Buddhist Experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Morganti, M. 2014. “Dependence, Justification and Explanation: Must Reality be Well‐founded?” Erkenntnis 80: 555–572.

- Newlands, S. 2013. “Leibniz and the Ground of Possibility.” Philosophical Review 122: 155–187.

- Paseau, A. 2010. “Defining Ultimate Ontological Basis and the Fundamental Layer.” Philosophical Quarterly 60: 169–175.

- Priest, G. 2014. One. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schaffer, J. 2003. “Is there a Fundamental Level?” Noûs 37: 498–517.

- Schaffer, J. 2009. “On What Grounds What.” In Metaphysics: New Essays in the Foundations of Ontology, edited by D. Manley, D. Chalmers, and R. Wasserman, 347–383. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schaffer, J. 2010. “Monism: The Priority of the Whole.” Philosophical Review 119: 31–76.

- Schaffer, J. 2012. “Grounding, Transitivity and Contrastivity.” In Metaphysical Grounding: Understanding the Structure of Reality, edited by F. Correia and B. Schnieder, 122–138. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Siderits, M. 2007. Buddhism as Philosophy. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Tahko, T.E. 2014. “Boring Infinite Descent.” Metaphilosophy 45: 257–269.

- Tahko, T.E. and Lowe, E.J. 2015. “Ontological Dependence.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by E. Zalta. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/dependence‐ontological/

- Williams, P. 2009. Mahāyāna Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations, 2nd edition. London: Routledge.