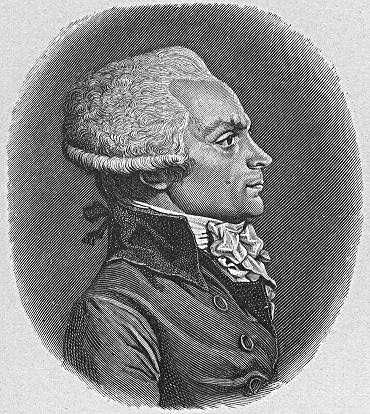

Maximilien de Robespierre (1758-1794):

The Enlightenment’s Butcher

Students of philosophy and history think of the Age of Enlightenment as Western Civilization’s glorious transition from the religious-based ignorance of the Middle Ages to modern-day secularism. What they do not learn, however, is that Enlightenment-era anti-rationalists, namely Maximilien de Robespierre, launched campaigns of widespread death and violence in the name of human advancement.

Robespierre was a student of Jacques Rousseau, who rejected the rationalist-based thought of the Enlightenment. According to Rousseau, feelings were a more reliable guide than reason. This notion was coupled with his faith-based belief in God and the conviction that all civil society must see their leaders as having religious power. If the people believed their leaders acted out of divine sentiment rather than reason, then the people would follow them. For Rousseau, the content of the belief did not have to correspond to traditional Christianity; any collective belief system would do. This was such an important concept that Rousseau wrote in The Social Contract that the state cannot tolerate disbelievers, even if they had personal reasons for this. Capital punishment was therefore appropriate for these people, as, “If, after having publicly recognized these dogmas, a person acts as if he does not believe them, he should be put to death.”

As Stephen Hicks presents in his book “Explaining Postmodernism,” following Rousseau’s death in 1778, Robespierre took up this call, particularly in the destructive third phase of the French Revolution. He was a member of the radical Jacobin Party and committed himself to Rousseau’s call to kill apostates from the collective identity of the state. He is quoted as saying: “Rousseau is the one man who, through the loftiness of his soul and the grandeur of his character, showed himself worthy of the role of teacher of mankind.” However, the lessons that Robespierre would apply from this teacher were to use the “universal compulsory force” Rousseau dreamed of to kill all those who did not agree with the extremist aims of a French Republic. As a result he and Jacobin sympathizers used the guillotine to kill nobles, priests, and anyone who had a hint of political opposition. Supporters marched through the streets of Paris with the heads of decapitated priests on the end of pikes. Thus begun the infamous Reign of Terror that reached its nadir with the 1793 executions of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, and it would not end until Robespierre's execution.

Born in 1758, Maxilimilien Marie Isidore de Robespierre hailed from Arras, France where he later served as a lawyer, opinion writer and the self-appointed public consciousness, touting the virtues of political change. Considered an extremist by many, Robespierre was vocal about his opinions very early in his public career. He was a strong advocate of equality and the dignity of all men. He rebuked the practice of slavery and was a proponent for basic human rights, not just the rights and privileges of property owners. His views naturally won him favor with the Jacobins, a radical political club committed to pursuing egalitarianism. Robespierre and his Jacobin cohorts escorted France into the Reign of Terror.

In 1788, Robespierre was elected to the Estates General, the French legislature, where he served until 1791. He often delivered speeches extolling the virtues of equality and morality. He was a harsh critic of King Louis XVI and most certainly contributed to the king’s eventual trial, conviction and execution two years later. The execution of the king only compounded troubles in France. The absence of a monarch sent the country into a tailspin of civil war, in addition to the threat of being overrun by other territories in Europe. In July, Robespierre, along with eight other officials, was elected to the Committee of Public Safety. Originally, the group was created as a watchdog group to protect the interests of France amidst the wars, chaos and rampant corruption. Its duties, of course, included singling out and bringing to justice those who conducted themselves in a manner that was not in the best interest of the republic. Almost immediately, terror was used as a surefire tactic for ensuring that those who would presume to do wrong were swiftly punished for their betrayal.

A moving and passionate orator, Robespierre warned listeners of the perils that would result from ignoring the chaos that threatened to paralyze France from within and defeat France from without. He insisted a revolution was in order. Over the course of one year, the Committee executed thousands of people -- those who were suspected of supporting the king or who had been accused of overthrowing the government. Many were executed without the benefit of going to trial to prove their innocence, or at least to disprove their guilt.

Central to his aims was marginalizing Christianity in society through the execution of priests and nuns. A notorious episode of Jacobin-inspired crowd violence is the prison massacres of 1792. Approximately 2,000 political prisoners, including priests and nuns, were dragged from their prison cells and executed. He was committed in his belief that such acts of terror against the clergy could actually serve to create public virtue: “The first maxim of our politics ought to be to lead the people by means of reason and the enemies of the people by terror...the basis of popular government in time of revolution is both virtue and terror: virtue without which terror is murderous, terror without which virtue is powerless. Terror is nothing else than swift, severe, indomitable justice; it flows, then, from virtue.”

Robespierre and the other members of the Committee faced strenuous and continuous opposition. The Committee’s actions were not improving the way of life for French citizens. The war was over, but prices were still going up and resources were still scarce. Now, in addition, citizens had to worry about Robespierre and his increasingly swift justice. Two of the more active groups who opposed The Committee, the Hebertists and the Indulgents, were adamant that the Committee’s conduct was no longer in the best interest of the republic. In response to their outcry, leaders from both groups were rounded up by the Committee and executed. Some of those executed had once been close personal friends and supporters of Robespierre.

The seeds for his downfall were planted in May 1794 when he had a decree passed by the Convention that affirmed a state deist religion known as the Cult of the Supreme Being. Furthermore the decree of 22 Prairial, which expedited executions by sentencing to death those only thought to be counter-revolutionaries, was presented to the public without passing the Committee. Terror was now an official government policy. Robespierre’s opponents were able to raise enough concern to have him and his supporters arrested. They were quickly released and while in the midst of planning their revenge, Robespierre and his entourage were themselves recaptured and executed without the benefit of trial, much like the thousands that had died in the immediate years previous for “opposing” the revolution.

His legacy is that of a brutal dictator who used the rhetoric of liberty to violently seize power. Despite his role in the French Revolution, he is disliked in his homeland. Today there is no statue in France for him; there is only a metro station in a poor suburb of Paris that bears his name. However, the most terrifying aspect of his legacy that has remained in popular imagination is that Robespierre was not a sneering monster beset by all of his terrible actions. He was not a cynic or a misanthrope. Rather, by all accounts he was a kind, polite man fully convinced that his actions were moral and virtuous. For this reason Ruth Scurr's biography of him is entitled “Fatal Purity.” His true danger came from the sincere belief that his actions were virtuous, which affirmed through every execution and infringement on human dignity. This clarity of purpose would stay with Robespierre all the way to his trip to the guillotine, in which one day before his execution he gave one last defense of terror to establish the French Republic:

“But there do exist, I can assure you, souls that are feeling and pure; it exists, that tender, imperious and irresistible passion, the torment and delight of magnanimous hearts; that deep horror of tyranny, that compassionate zeal for the oppressed, that sacred love for the homeland, that even more sublime and holy love for humanity, without which a great revolution is just a noisy crime that destroys another crime; it does exist, that generous ambition to establish here on earth the world's first Republic.”