The way you think and feel about gardens and the things growing in them—flowers, vegetables—I can see must depend on where you come from, and I don’t mean the difference in opinion and feeling between a person from Spain and a person from England but a difference like this:

The implements of the little feast had been disposed upon the lawn of an old English country-house, in what I should call the perfect middle of a splendid summer afternoon. Part of the afternoon had waned, but much of it was left, and what was left was of the finest and rarest quality. Real dusk would not arrive for many hours; but the flood of summer light had begun to ebb, the air had grown mellow, the shadows

were long upon the smooth, dense turf … The great still oaks and beeches flung down a shade as dense as that of velvet curtains; and the place was furnished, like a room, with cushioned seats, with rich-coloured rugs, with the books and papers that lay upon the grass.

And this:

The smooth, stoneless drive ran between squat, robust conifers on one side and a blaze of canna lilies burning scarlet and amber on the other. Plants like that belonged to the cities. They had belonged to the pages of my language reader, to the yards of Ben and Betty’s uncle in town. Now, having seen it for myself because of my Babamukuru’s kindness, I too could think of planting things for merrier reasons than the chore of keeping breath in the body. I wrote it down in my head: I would ask Maiguru for some bulbs and plant a bed of those gay lilies on the homestead. In front of the house. Our home would answer well to being cheered up by such lovely flowers. Bright and cheery, they had been planted for joy. What a strange idea that was. It was a liberation, the first of many that followed from my transition to the mission.

The first quotation is from Henry James’s novel The Portrait of a Lady, and it can be found isolated in a book called Pleasures of the Garden: Images from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, by Mac Griswold, beneath a painting by Pierre Bonnard called The Terrace at Vernon.

The painting is rich, rich, rich: rich in color (a profusion of reds, oranges, yellows, blues, greens), rich in material things, rich in bounty from the land. And the quotation itself, with its “little feast,” its luxurious observations “splendid summer afternoon” and “flood of summer light,” could have been written only by a person who comes from a place where the wealth of the world is like a skin, a natural part of the body, a right, assumed, like having two hands and on them five fingers each.

It is the second quotation that immediately means something to me, especially this: “Bright and cheery, they had been planted for joy. What a strange idea that was.” These sentences are from a novel called Nervous Conditions, by a woman from Zimbabwe named Tsitsi Dangarembga, and I suppose it is a coming-of-age novel (and really, most people who come from the far parts of the world who write books write at some point about their childhood—I believe it is a coincidence); but the book is also a description of brutality, foreign and local. There are the ingredients for a garden—a plot of land, a hoe, some seeds—but they do not lead to little feasts; they lead to nothing or they lead to work, and not work as an act of self-definition, self-acclaim, but work as torture, work as hell. And so it is quite appropriate that the young narrator—her name is Tambu—finds in the sight of things growing just for the sheer joy of it, liberation.

And what is the relationship between gardening and conquest? Is the conqueror a gardener and the conquered the person who works in the field? The climate of southern Africa is not one that has only recently become hospitable to flowering herbs, and so it is quite possible (most likely) that the ancestors of this girl Tambu would have noticed them and cultivated them, not only for their medicinal value,

but also for the sheer joy of seeing them all by themselves in their loveliness, in afternoons that were waning, in light that had begun to ebb. At what moment was this idea lost? At what moment does such ordinary, everyday beauty become a luxury?

When the Spanish marauder Hernando Cortez and his army invaded Mexico, they met “floating gardens … teeming with flowers and vegetables, and moving like rafts over the waters”; as they looked down on the valley of Mexico, seeing it for the first time, a “picturesque assemblage of water, woodland, and cultivated plains, its shining cities and shadowy hills, was spread out like some gay and gorgeous panorama before them,” and “stretching far away at their feet were seen noble forests of oak, sycamore, and cedar, and beyond, yellow fields of maize and the towering maguey, intermingled with orchards and blooming gardens”; there were “flowers, which, with their variegated and gaudy colors, form the greatest attraction of our greenhouses”; and again: “Extensive gardens were spread … filled with fragrant shrubs and flowers, and especially with medicinal plants. No country has afforded more numerous species of these last … and their virtues were perfectly understood by the Aztecs, with whom medical botany may be said to have been studied as a science.” (All this is from The Conquest of Mexico, by William H. Prescott, and it is the best history of conquest I have ever read.) Quite likely, within a generation most of the inhabitants of this place (Mexico), spiritually devastated, would have lost touch with that strange idea—things planted for no other reason than the sheer joy of it.

Certainly if after the conquest an Aztec had gone into a shop and

said “It’s my husband’s birthday. I would like to give him some flowers. May I have a bunch of cocoxochitl, please?” no one would have been able to help her, because cocoxochitl was no longer the name of that flower. It had become the dahlia. In its place of origin (Mexico, Central America), the people who lived there had no dahliamania, no Dahlia Societies, no dinner-plate-size dahlia, no peony-, no anemone-, no ball-shaped-, no water-lily-, no pompon-flowered dahlia. The flower seems to have been appreciated and cultivated for its own sake and for its medicinal value (urinary-tract disorders—cocoxochitl means “water pipes”) and as animal fodder. And understandably, beautiful as this flower would have appeared to these people, there were so many other flowers and shrubs and trees and vines, each with some overpowering attribute of shape, height, color of bloom, and scent, that it would not be singled out; the sight of this flower would not have inspired in these people a single criminal act.

At what moment is the germ of possession lodged in the heart? When another Spanish marauder, Vasco Núñez de Balboa, was within sight of the Pacific Ocean, he made his army stay behind him, so that he could be the first person like himself (a European person) to see this ocean; it is likely that could this ocean have been taken up and removed to somewhere else (Spain, Portugal, England), the people for whom it had become a spiritual fixture would long for it and at the same time not even know what it was they were missing. And so the dahlia: Who first saw it and longed for it so deeply that it was removed from the place where it had always been, and transformed (hybridized), and renamed? Hernando Cortez would not have noticed it; to him the dahlia would have been one of the details, a small detail, of something large and grim: conquest. The dahlia went to Europe; it

was hybridized by the Swedish botanist Andreas Dahl, after whom it was renamed.

I was once in a garden in the mountains way above Kingston (Jamaica), and from a distance I saw a mass of tall stalks of red flames, something in bloom. It looked familiar, but what it resembled, what it reminded me of, was a flower I cannot stand, and these flowers I saw before me I immediately loved, and they made me feel glad for the millionth time that I am from the West Indies. (This worthless feeling, this bestowing special qualities on yourself because of the beauty of the place you are from, is hard to resist—so hard that people who come from the ugliest place deny that it is ugly at all or simply go out and take someone else’s beauty for themselves.) These flowering stalks of red flames turned out to be salvia, but I knew it was salvia only because I had seen it grown—a much shorter variety—in North American gardens; and I realized that I cannot stand it when I see it growing in the north because that shade of red can’t be borne well by a dwarfish plant.

I do not know the names of the plants in the place I am from (Antigua). I can identify the hibiscus, but I do not know the name of a white lily that blooms in July, opening at night, perfuming the air with a sweetness that is almost sickening, and closing up at dawn. There is a bush called whitehead bush; it was an important ingredient in the potions my mother and her friends made for their abortions, but I do not know its proper name; this same bush I often had to go and cut down and tie in bunches to make a broom for sweeping our yard; both the abortions and the sweeping of the yard, actions deep and shallow, in a place like that (Antigua) would fall into the category

called Household Management. I had wanted to see the garden in Kingston so that I could learn the names of some flowers in the West Indies, but along with the salvia the garden had in it only roses and a single anemic-looking yellow lupine (and this surprised me, because lupine is a temperate zone flower and I had very recently seen it in bloom along the roadside of a town in Finland).

This ignorance of the botany of the place I am from (and am of) really only reflects the fact that when I lived there, I was of the conquered class and living in a conquered place; a principle of this condition is that nothing about you is of any interest unless the conqueror deems it so. For instance, there was a botanical garden not far from where I lived, and in it were plants from various parts of the then British Empire, places that had the same climate as my own; but as I remember, none of the plants were native to Antigua. The rubber tree from Malaysia (or somewhere) is memorable because in the year my father and I were sick at the same time (he with heart disease, I with hookworms), we would go and sit under this tree after we ate our lunch, and under this tree he would tell me about his parents, who had abandoned him and gone off to build the Panama Canal (though of course he disguised the brutality of this). The bamboo grove is memorable because it was there I used to meet people I was in love with. The botanical garden reinforced for me how powerful were the people who had conquered me; they could bring to me the botany of the world they owned. It wouldn’t at all surprise me to learn that in Malaysia (or somewhere) was a botanical garden with no plants native to that place.

There was a day not long ago when I realized with a certain amount of bitterness that I was in my garden, a flower garden, a garden planted

only because I wished to have such a thing, and that I knew how I wanted it to look and knew the name, proper and common, of each thing growing in it. In the place I am from, I would have been a picture of shame: a woman covered with dirt, smelling of manure, her hair flecked with white dust (powdered lime), her body a cauldron of smells pleasing to her, and her back crooked with pain from bending over. In the place I am from, I would not have allowed a man with the same description as such a woman to kiss me.

It is understandable that a man like Andreas Dahl would not have demurred at his eponymous honor, because this was the eighteenth century and the honor was bestowed on him by a king (a Charles of Spain, who might well have named the flower after himself, or a close relative, or any one of the many henchmen in his service). Andreas Dahl was very familiar with the habit of naming, for he had been a pupil of Carlolus Linnaeus. This man, Carlolus Linnaeus, had been a botanist and a doctor, and that made sense, botanist and doctor: they went together because plants were the main source of medicine in that part of the world then, as was true in the other parts of the world then also. From Sweden (his place of origin) he had gone to the Netherlands for his doctor’s degree, and it was there, while serving as personal physician to a rich man, that he worked out his system (binomial) of naming plants. The rich man (his name was George Clifford) had four greenhouses filled with plants not native to the Netherlands—not native to Europe at all but native to the places that had been recently conquered. The Oxford Companion to Gardens (a book I often want to hurl across the room, it is so full of prejudice) describes Linnaeus as “enraptured” with seeing all these plants from far away, because his native Sweden did not have anything like them, but most likely what

happened was that he saw an opportunity, and it was this: These countries in Europe shared the same botany, more or less, but each place called the same thing by a different name; and these people who make up Europe were (are) so contentious anyway, they would not have agreed to one system for all the plants they had in common, but these new plants from far away, like the people far away, had no history, no names, and so they could be given names. And who was there to dispute Linnaeus, even if there was someone who would listen?

This naming of things is so crucial to possession—a spiritual padlock with the key thrown irretrievably away—that it is a murder, an erasing, and it is not surprising that when people have felt themselves prey to it (conquest), among their first acts of liberation is to change their names (Rhodesia to Zimbabwe, LeRoi Jones to Amiri Baraka). That the great misery and much smaller joy of existence remain unchanged no matter what anything is called never checks the impulse to reach back and reclaim a loss, to try and make what happened look as if it had not happened at all.

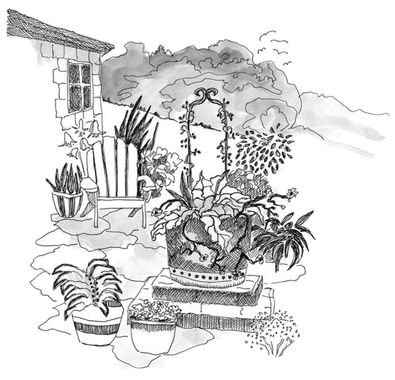

As I started to write this (at the very beginning) I was sitting at a window that looked out over my own garden, a new one (I have just moved to this place), and my eye began in the deep-shade area, where I had planted some astilbe and hosta and Ranunculus repens, and I thought how beautifully the leaves of the astilbe went with the leaves of the ranunculus, and I took pleasure in that, because in putting things together (plants) you never really know how it will all work until they do something, like bloom. (It will be two or three years before I know whether the clematis really will run up the rosebushes and bloom together with them and whether it will really look the way I have imagined.) Just now the leaves in the shade bed are all complementary

(but not in a predictable way—in a way I had not expected, a thrilling way). And I thought how I had crossed a line; but at whose expense? I cannot begin to look, because what if it is someone I know? I have joined the conquering class: who else could afford this garden—a garden in which I grow things that it would be much cheaper to buy at the store?

My feet are (so to speak) in two worlds, I was thinking as I looked farther into the garden and saw, beyond the pumpkin patch, a fox emerge from the hedge—the same spot in the hedge where I have seen the rabbits and a family of malicious woodchucks emerge (the

woodchucks to eat not the lettuce or the beans or the other things I would expect them to eat but the tender new shoots and tendrils of the squash vines). The fox crossed the garden and ran behind the shed, and I could see him clearly, his face a set of sharp angles, his cheeks planed, his body a fabric of tightly woven gray and silver hair over a taut frame of sinew and bones, his tail a perfect furpiece. He disappeared into the opposite hedge and field; he, too, had the look of the marauder, wandering around hedge and field looking for prey. That night, lying in my bed, I heard from beyond the hedge where he had emerged sounds of incredible agony; he must have found his prey; but the fox is in nature, and in nature things work that way.

I am not in nature. I do not find the world furnished like a room, with cushioned seats and rich-colored rugs. To me, the world is cracked, unwhole, not pure, accidental; and the idea of moments of joy for no reason is very strange.