Thorndyke was not a newspaper reader. He viewed with extreme disfavour all scrappy and miscellaneous forms of literature, which, by presenting a disorderly series of unrelated items of information, tended, as he considered, to destroy the habit of consecutive mental effort.

“It is most important,” he once remarked to me, “habitually to pursue a definite train of thought, and to pursue it to a finish, instead of flitting indolently from one uncompleted topic to another, as the newspaper reader is so apt to do. Still, there is no harm in a daily paper—so long as you don’t read it.”

Accordingly, he patronized a morning paper, and his method of dealing with it was characteristic. The paper was laid on the table after breakfast, together with a blue pencil and a pair of office shears. A preliminary glance through the sheets enabled him to mark with the pencil those paragraphs that were to be read, and these were presently cut out and looked through, after which they were either thrown away or set aside to be pasted in an indexed book.

The whole proceeding occupied, on an average, a quarter of an hour.

On the morning of which I am now speaking he was thus engaged. The pencil had done its work, and the snick of the shears announced the final stage. Presently he paused with a newly-excised cutting between his fingers, and, after glancing at it for a moment, he handed it to me.

“Another art robbery,” he remarked. “Mysterious affairs, these—as to motive, I mean. You can’t melt down a picture or an ivory carving, and you can’t put them on the market as they stand. The very qualities that give them their value make them totally unnegotiable.”

“Yet I suppose,” said I, “the really inveterate collector—the pottery or stamp maniac, for instance—will buy these contraband goods even though he dare not show them.”

“Probably. No doubt the cupiditas habendi, the mere desire to possess, is the motive force rather than any intelligent purpose—”

The discussion was at this point interrupted by a knock at the door, and a moment later my colleague admitted two gentlemen. One of these I recognized as a Mr. Marchmont, a solicitor, for whom we had occasionally acted; the other was a stranger—a typical Hebrew of the blonde type—good-looking, faultlessly dressed, carrying a bandbox, and obviously in a state of the most extreme agitation.

“Good-morning to you, gentlemen,” said Mr. Marchmont, shaking hands cordially. “I have brought a client of mine to see you, and when I tell you that his name is Solomon Löwe, it will be unnecessary for me to say what our business is.”

“Oddly enough,” replied Thorndyke, “we were, at the very moment when you knocked, discussing the bearings of his case.”

“It is a horrible affair!” burst in Mr. Löwe. “I am distracted! I am ruined! I am in despair!”

He banged the bandbox down on the table, and flinging himself into a chair, buried his face in his hands.

“Come, come,” remonstrated Marchmont, “we must be brave, we must be composed. Tell Dr. Thorndyke your story, and let us hear what he thinks of it.”

He leaned back in his chair, and looked at his client with that air of patient fortitude that comes to us all so easily when we contemplate the misfortunes of other people.

“You must help us, sir,” exclaimed Löwe, starting up again—“you must, indeed, or I shall go mad. But I shall tell you what has happened, and then you must act at once. Spare no effort and no expense. Money is no object—at least, not in reason,” he added, with native caution. He sat down once more, and in perfect English, though with a slight German accent, proceeded volubly: “My brother Isaac is probably known to you by name.”

Thorndyke nodded.

“He is a great collector, and to some extent a dealer—that is to say, he makes his hobby a profitable hobby.”

“What does he collect?” asked Thorndyke.

“Everything,” replied our visitor, flinging his hands apart with a comprehensive gesture—“everything that is precious and beautiful—pictures, ivories, jewels, watches, objects of art and vertu—everything. He is a Jew, and he has that passion for things that are rich and costly that has distinguished our race from the time of my namesake Solomon onwards. His house in Howard Street, Piccadilly, is at once a museum and an art gallery. The rooms are filled with cases of gems, of antique jewellery, of coins and historic relics—some of priceless value—and the walls are covered with paintings, every one of which is a masterpiece. There is a fine collection of ancient weapons and armour, both European and Oriental; rare books, manuscripts, papyri, and valuable antiquities from Egypt, Assyria, Cyprus, and elsewhere. You see, his taste is quite catholic, and his knowledge of rare and curious things is probably greater than that of any other living man. He is never mistaken. No forgery deceives him, and hence the great prices that he obtains; for a work of art purchased from Isaac Löwe is a work certified as genuine beyond all cavil.”

He paused to mop his face with a silk handkerchief, and then, with the same plaintive volubility, continued:

“My brother is unmarried. He lives for his collection, and he lives with it. The house is not a very large one, and the collection takes up most of it; but he keeps a suite of rooms for his own occupation, and has two servants—a man and wife—to look after him. The man, who is a retired police sergeant, acts as caretaker and watchman; the woman as housekeeper and cook, if required, but my brother lives largely at his club. And now I come to this present catastrophe.”

He ran his fingers through his hair, took a deep breath, and continued:

“Yesterday morning Isaac started for Florence by way of Paris, but his route was not certain, and he intended to break his journey at various points as circumstances determined. Before leaving, he put his collection in my charge, and it was arranged that I should occupy his rooms in his absence. Accordingly, I sent my things round and took possession.

“Now, Dr. Thorndyke, I am closely connected with the drama, and it is my custom to spend my evenings at my club, of which most of the members are actors. Consequently, I am rather late in my habits; but last night I was earlier than usual in leaving my club, for I started for my brother’s house before half-past twelve. I felt, as you may suppose, the responsibility of the great charge I had undertaken; and you may, therefore, imagine my horror, my consternation, my despair, when, on letting myself in with my latchkey, I found a police-inspector, a sergeant, and a constable in the hall. There had been a robbery, sir, in my brief absence, and the account that the inspector gave of the affair was briefly this:

“While taking the round of his district, he had noticed an empty hansom proceeding in leisurely fashion along Howard Street. There was nothing remarkable in this, but when, about ten minutes later, he was returning, and met a hansom, which he believed to be the same, proceeding along the same street in the same direction, and at the same easy pace, the circumstance struck him as odd, and he made a note of the number of the cab in his pocket-book. It was 72,863, and the time was 11:35.

“At 11:45 a constable coming up Howard Street noticed a hansom standing opposite the door of my brother’s house, and, while he was looking at it, a man came out of the house carrying something, which he put in the cab. On this the constable quickened his pace, and when the man returned to the house and reappeared carrying what looked like a portmanteau, and closing the door softly behind him, the policeman’s suspicions were aroused, and he hurried forward, hailing the cabman to stop.

“The man put his burden into the cab, and sprang in himself. The cabman lashed his horse, which started off at a gallop, and the policeman broke into a run, blowing his whistle and flashing his lantern on to the cab. He followed it round the two turnings into Albemarle Street, and was just in time to see it turn into Piccadilly, where, of course, it was lost. However, he managed to note the number of the cab, which was 72,863, and he describes the man as short and thick-set, and thinks he was not wearing any hat.

“As he was returning, he met the inspector and the sergeant, who had heard the whistle, and on his report the three officers hurried to the house, where they knocked and rang for some minutes without any result. Being now more than suspicious, they went to the back of the house, through the mews, where, with great difficulty, they managed to force a window and effect an entrance into the house.

“Here their suspicions were soon changed to certainty, for, on reaching the first-floor, they heard strange muffled groans proceeding from one of the rooms, the door of which was locked, though the key had not been removed. They opened the door, and found the caretaker and his wife sitting on the floor, with their backs against the wall. Both were bound hand and foot, and the head of each was enveloped in a green-baize bag; and when the bags were taken off, each was found to be lightly but effectively gagged.

“Each told the same story. The caretaker, fancying he heard a noise, armed himself with a truncheon, and came downstairs to the first-floor, where he found the door of one of the rooms open, and a light burning inside. He stepped on tiptoe to the open door, and was peering in, when he was seized from behind, half suffocated by a pad held over his mouth, pinioned, gagged, and blindfolded with the bag.

“His assailant—whom he never saw—was amazingly strong and skilful, and handled him with perfect ease, although he—the caretaker—is a powerful man, and a good boxer and wrestler. The same thing happened to the wife, who had come down to look for her husband. She walked into the same trap, and was gagged, pinioned, and blindfolded without ever having seen the robber. So the only description that we have of this villain is that furnished by the constable.”

“And the caretaker had no chance of using his truncheon?” said Thorndyke.

“Well, he got in one backhanded blow over his right shoulder, which he thinks caught the burglar in the face; but the fellow caught him by the elbow, and gave his arm such a twist that he dropped the truncheon on the floor.”

“Is the robbery a very extensive one?”

“Ah!” exclaimed Mr. Löwe, “that is just what we cannot say. But I fear it is. It seems that my brother had quite recently drawn out of his bank four thousand pounds in notes and gold. These little transactions are often carried out in cash rather than by cheque”—here I caught a twinkle in Thorndyke’s eye—“and the caretaker says that a few days ago Isaac brought home several parcels, which were put away temporarily in a strong cupboard. He seemed to be very pleased with his new acquisitions, and gave the caretaker to understand that they were of extraordinary rarity and value.

“Now, this cupboard has been cleared out. Not a vestige is left in it but the wrappings of the parcels, so, although nothing else has been touched, it is pretty clear that goods to the value of four thousand pounds have been taken; but when we consider what an excellent buyer my brother is, it becomes highly probable that the actual value of those things is two or three times that amount, or even more. It is a dreadful, dreadful business, and Isaac will hold me responsible for it all.”

“Is there no further clue?” asked Thorndyke. “What about the cab, for instance?”

“Oh, the cab,” groaned Löwe—“that clue failed. The police must have mistaken the number. They telephoned immediately to all the police stations, and a watch was set, with the result that number 72,863 was stopped as it was going home for the night. But it then turned out that the cab had not been off the rank since eleven o’clock, and the driver had been in the shelter all the time with several other men. But there is a clue; I have it here.”

Mr. Löwe’s face brightened for once as he reached out for the bandbox.

“The houses in Howard Street,” he explained, as he untied the fastening, “have small balconies to the first-floor windows at the back. Now, the thief entered by one of these windows, having climbed up a rain-water pipe to the balcony. It was a gusty night, as you will remember, and this morning, as I was leaving the house, the butler next door called to me and gave me this; he had found it lying in the balcony of his house.”

He opened the bandbox with a flourish, and brought forth a rather shabby billycock hat.

“I understand,” said he, “that by examining a hat it is possible to deduce from it, not only the bodily characteristics of the wearer, but also his mental and moral qualities, his state of health, his pecuniary position, his past history, and even his domestic relations and the peculiarities of his place of abode. Am I right in this supposition?”

The ghost of a smile flitted across Thorndyke’s face as he laid the hat upon the remains of the newspaper. “We must not expect too much,” he observed. “Hats, as you know, have a way of changing owners. Your own hat, for instance” (a very spruce, hard felt), “is a new one, I think.”

“Got it last week,” said Mr. Löwe.

“Exactly. It is an expensive hat, by Lincoln and Bennett, and I see you have judiciously written your name in indelible marking-ink on the lining. Now, a new hat suggests a discarded predecessor. What do you do with your old hats?”

“My man has them, but they don’t fit him. I suppose he sells them or gives them away.”

“Very well. Now, a good hat like yours has a long life, and remains serviceable long after it has become shabby; and the probability is that many of your hats pass from owner to owner; from you to the shabby-genteel, and from them to the shabby ungenteel. And it is a fair assumption that there are, at this moment, an appreciable number of tramps and casuals wearing hats by Lincoln and Bennett, marked in indelible ink with the name S. Löwe; and anyone who should examine those hats, as you suggest, might draw some very misleading deductions as to the personal habits of S. Löwe.”

Mr. Marchmont chuckled audibly, and then, remembering the gravity of the occasion, suddenly became portentously solemn.

“So you think that the hat is of no use, after all?” said Mr. Löwe, in a tone of deep disappointment.

“I won’t say that,” replied Thorndyke. “We may learn something from it. Leave it with me, at any rate; but you must let the police know that I have it. They will want to see it, of course.”

“And you will try to get those things, won’t you?” pleaded Löwe.

“I will think over the case. But you understand, or Mr. Marchmont does, that this is hardly in my province. I am a medical jurist, and this is not a medico-legal case.”

“Just what I told him,” said Marchmont. “But you will do me a great kindness if you will look into the matter. Make it a medico-legal case,” he added persuasively.

Thorndyke repeated his promise, and the two men took their departure.

For some time after they had left, my colleague remained silent, regarding the hat with a quizzical smile. “It is like a game of forfeits,” he remarked at length, “and we have to find the owner of ‘this very pretty thing.’” He lifted it with a pair of forceps into a better light, and began to look at it more closely.

“Perhaps,” said he, “we have done Mr. Löwe an injustice, after all. This is certainly a very remarkable hat.”

“It is as round as a basin,” I exclaimed. “Why, the fellow’s head must have been turned in a lathe!”

Thorndyke laughed. “The point,” said he, “is this. This is a hard hat, and so must have fitted fairly, or it could not have been worn; and it was a cheap hat, and so was not made to measure. But a man with a head that shape has got to come to a clear understanding with his hat. No ordinary hat would go on at all.

“Now, you see what he has done—no doubt on the advice of some friendly hatter. He has bought a hat of a suitable size, and he has made it hot—probably steamed it. Then he has jammed it, while still hot and soft, on to his head, and allowed it to cool and set before removing it. That is evident from the distortion of the brim. The important corollary is, that this hat fits his head exactly—is, in fact, a perfect mould of it; and this fact, together with the cheap quality of the hat, furnishes the further corollary that it has probably only had a single owner.

“And now let us turn it over and look at the outside. You notice at once the absence of old dust. Allowing for the circumstance that it had been out all night, it is decidedly clean. Its owner has been in the habit of brushing it, and is therefore presumably a decent, orderly man. But if you look at it in a good light, you see a kind of bloom on the felt, and through this lens you can make out particles of a fine white powder which has worked into the surface.”

He handed me his lens, through which I could distinctly see the particles to which he referred.

“Then,” he continued, “under the curl of the brim and in the folds of the hatband, where the brush has not been able to reach it, the powder has collected quite thickly, and we can see that it is a very fine powder, and very white, like flour. What do you make of that?”

“I should say that it is connected with some industry. He may be engaged in some factory or works, or, at any rate, may live near a factory, and have to pass it frequently.”

“Yes; and I think we can distinguish between the two possibilities. For, if he only passes the factory, the dust will be on the outside of the hat only; the inside will be protected by his head. But if he is engaged in the works, the dust will be inside, too, as the hat will hang on a peg in the dust-laden atmosphere, and his head will also be powdered, and so convey the dust to the inside.”

He turned the hat over once more, and as I brought the powerful lens to bear upon the dark lining, I could clearly distinguish a number of white particles in the interstices of the fabric.

“The powder is on the inside, too,” I said.

He took the lens from me, and, having verified my statement, proceeded with the examination. “You notice,” he said, “that the leather head-lining is stained with grease, and this staining is more pronounced at the sides and back. His hair, therefore, is naturally greasy, or he greases it artificially; for if the staining were caused by perspiration, it would be most marked opposite the forehead.”

He peered anxiously into the interior of the hat, and eventually turned down the head-lining; and immediately there broke out upon his face a gleam of satisfaction.

“Ha!” he exclaimed. “This is a stroke of luck. I was afraid our neat and orderly friend had defeated us with his brush. Pass me the small dissecting forceps, Jervis.”

I handed him the instrument, and he proceeded to pick out daintily from the space behind the head-lining some half a dozen short pieces of hair, which he laid, with infinite tenderness, on a sheet of white paper.

“There are several more on the other side,” I said, pointing them out to him.

“Yes, but we must leave some for the police,” he answered, with a smile. “They must have the same chance as ourselves, you know.”

“But surely,” I said, as I bent down over the paper, “these are pieces of horsehair!”

“I think not,” he replied; “but the microscope will show. At any rate, this is the kind of hair I should expect to find with a head of that shape.”

“Well, it is extraordinarily coarse,” said I, “and two of the hairs are nearly white.”

“Yes; black hairs beginning to turn grey. And now, as our preliminary survey has given such encouraging results, we will proceed to more exact methods; and we must waste no time, for we shall have the police here presently to rob us of our treasure.”

He folded up carefully the paper containing the hairs, and taking the hat in both hands, as though it were some sacred vessel, ascended with me to the laboratory on the next floor.

“Now, Polton,” he said to his laboratory assistant, “we have here a specimen for examination, and time is precious. First of all, we want your patent dust-extractor.”

The little man bustled to a cupboard and brought forth a singular appliance, of his own manufacture, somewhat like a miniature vacuum cleaner. It had been made from a bicycle foot-pump, by reversing the piston-valve, and was fitted with a glass nozzle and a small detachable glass receiver for collecting the dust, at the end of a flexible metal tube.

“We will sample the dust from the outside first,” said Thorndyke, laying the hat upon the work-bench. “Are you ready, Polton?”

The assistant slipped his foot into the stirrup of the pump and worked the handle vigorously, while Thorndyke drew the glass nozzle slowly along the hat-brim under the curled edge. And as the nozzle passed along, the white coating vanished as if by magic, leaving the felt absolutely clean and black, and simultaneously the glass receiver became clouded over with a white deposit.

“We will leave the other side for the police,” said Thorndyke, and as Polton ceased pumping he detached the receiver, and laid it on a sheet of paper, on which he wrote in pencil, “Outside,” and covered it with a small bell-glass. A fresh receiver having been fitted on, the nozzle was now drawn over the silk lining of the hat, and then through the space behind the leather head-lining on one side; and now the dust that collected in the receiver was much of the usual grey colour and fluffy texture, and included two more hairs.

“And now,” said Thorndyke, when the second receiver had been detached and set aside, “we want a mould of the inside of the hat, and we must make it by the quickest method; there is no time to make a paper mould. It is a most astonishing head,” he added, reaching down from a nail a pair of large callipers, which he applied to the inside of the hat; “six inches and nine-tenths long by six and six-tenths broad, which gives us”—he made a rapid calculation on a scrap of paper—“the extraordinarily high cephalic index of 95•6.”

Polton now took possession of the hat, and, having stuck a band of wet tissue-paper round the inside, mixed a small bowl of plaster-of-Paris, and very dexterously ran a stream of the thick liquid on to the tissue-paper, where it quickly solidified. A second and third application resulted in a broad ring of solid plaster an inch thick, forming a perfect mould of the inside of the hat, and in a few minutes the slight contraction of the plaster in setting rendered the mould sufficiently loose to allow of its being slipped out on to a board to dry.

We were none too soon, for even as Polton was removing the mould, the electric bell, which I had switched on to the laboratory, announced a visitor, and when I went down I found a police-sergeant waiting with a note from Superintendent Miller, requesting the immediate transfer of the hat.

“The next thing to be done,” said Thorndyke, when the sergeant had departed with the bandbox, “is to measure the thickness of the hairs, and make a transverse section of one, and examine the dust. The section we will leave to Polton—as time is an object, Polton, you had better imbed the hair in thick gum and freeze it hard on the microtome, and be very careful to cut the section at right angles to the length of the hair—meanwhile, we will get to work with the microscope.”

The hairs proved on measurement to have the surprisingly large diameter of 1/135 of an inch—fully double that of ordinary hairs, although they were unquestionably human. As to the white dust, it presented a problem that even Thorndyke was unable to solve. The application of reagents showed it to be carbonate of lime, but its source for a time remained a mystery.

“The larger particles,” said Thorndyke, with his eye applied to the microscope, “appear to be transparent, crystalline, and distinctly laminated in structure. It is not chalk, it is not whiting, it is not any kind of cement. What can it be?”

“Could it be any kind of shell?” I suggested. “For instance—”

“Of course!” he exclaimed, starting up; “you have hit it, Jervis, as you always do. It must be mother-of-pearl. Polton, give me a pearl shirt-button out of your oddments box.”

The button was duly produced by the thrifty Polton, dropped into an agate mortar, and speedily reduced to powder, a tiny pinch of which Thorndyke placed under the microscope.

“This powder,” said he, “is, naturally, much coarser than our specimen, but the identity of character is unmistakable. Jervis, you are a treasure. Just look at it.”

I glanced down the microscope, and then pulled out my watch. “Yes,” I said, “there is no doubt about it, I think; but I must be off. Anstey urged me to be in court by 11:30 at the latest.”

With infinite reluctance I collected my notes and papers and departed, leaving Thorndyke diligently copying addresses out of the Post Office Directory.

My business at the court detained me the whole of the day, and it was near upon dinner-time when I reached our chambers. Thorndyke had not yet come in, but he arrived half an hour later, tired and hungry, and not very communicative.

“What have I done?” he repeated, in answer to my inquiries. “I have walked miles of dirty pavement, and I have visited every pearl-shell cutter’s in London, with one exception, and I have not found what I was looking for. The one mother-of-pearl factory that remains, however, is the most likely, and I propose to look in there to-morrow morning. Meanwhile, we have completed our data, with Polton’s assistance. Here is a tracing of our friend’s skull taken from the mould; you see it is an extreme type of brachycephalic skull, and markedly unsymmetrical. Here is a transverse section of his hair, which is quite circular—unlike yours or mine, which would be oval. We have the mother-of-pearl dust from the outside of the hat, and from the inside similar dust mixed with various fibres and a few granules of rice starch. Those are our data.”

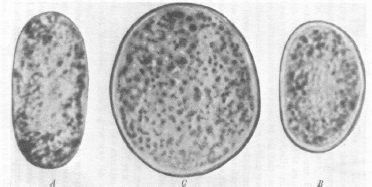

Transverse sections of human hair: A, of a Negro; B, of an Englishman; C, of the Burglar. All magnified 600 diameters.

“Supposing the hat should not be that of the burglar after all?” I suggested.

“That would be annoying. But I think it is his, and I think I can guess at the nature of the art treasures that were stolen.”

“And you don’t intend to enlighten me?”

“My dear fellow,” he replied, “you have all the data. Enlighten yourself by the exercise of your own brilliant faculties. Don’t give way to mental indolence.”

I endeavoured, from the facts in my possession, to construct the personality of the mysterious burglar, and failed utterly; nor was I more successful in my endeavour to guess at the nature of the stolen property; and it was not until the following morning, when we had set out on our quest and were approaching Limehouse, that Thorndyke would revert to the subject.

“We are now,” he said, “going to the factory of Badcomb and Martin, shell importers and cutters, in the West India Dock Road. If I don’t find my man there, I shall hand the facts over to the police, and waste no more time over the case.”

“What is your man like?” I asked.

“I am looking for an elderly Japanese, wearing a new hat or, more probably, a cap, and having a bruise on his right cheek or temple. I am also looking for a cab-yard; but here we are at the works, and as it is now close on the dinner-hour, we will wait and see the hands come out before making any inquiries.”

We walked slowly past the tall, blank-faced building, and were just turning to re-pass it when a steam whistle sounded, a wicket opened in the main gate, and a stream of workmen—each powdered with white, like a miller—emerged into the street. We halted to watch the men as they came out, one by one, through the wicket, and turned to the right or left towards their homes or some adjacent coffee-shop; but none of them answered to the description that my friend had given.

The outcoming stream grew thinner, and at length ceased; the wicket was shut with a bang, and once more Thorndyke’s quest appeared to have failed.

“Is that all of them, I wonder?” he said, with a shade of disappointment in his tone; but even as he spoke the wicket opened again, and a leg protruded. The leg was followed by a back and a curious globular head, covered with iron-grey hair, and surmounted by a cloth cap, the whole appertaining to a short, very thick-set man, who remained thus, evidently talking to someone inside.

Suddenly he turned his head to look across the street; and immediately I recognized, by the pallid yellow complexion and narrow eye-slits, the physiognomy of a typical Japanese. The man remained talking for nearly another minute; then, drawing out his other leg, he turned towards us; and now I perceived that the right side of his face, over the prominent cheekbone, was discoloured as though by a severe bruise.

“Ha!” said Thorndyke, turning round sharply as the man approached, “either this is our man or it is an incredible coincidence.” He walked away at a moderate pace, allowing the Japanese to overtake us slowly, and when the man had at length passed us, he increased his speed somewhat, so as to maintain the distance.

Our friend stepped along briskly, and presently turned up a side street, whither we followed at a respectful distance, Thorndyke holding open his pocket-book, and appearing to engage me in an earnest discussion, but keeping a sharp eye on his quarry.

“There he goes!” said my colleague, as the man suddenly disappeared—“the house with the green window-sashes. That will be number thirteen.”

It was; and, having verified the fact, we passed on, and took the next turning that would lead us back to the main road.

Some twenty minutes later, as we were strolling past the door of a coffee-shop, a man came out, and began to fill his pipe with an air of leisurely satisfaction. His hat and clothes were powdered with white like those of the workmen whom we had seen come out of the factory. Thorndyke accosted him.

“Is that a flour-mill up the road there?”

“No, sir; pearl-shell. I work there myself.”

“Pearl-shell, eh?” said Thorndyke. “I suppose that will be an industry that will tend to attract the aliens. Do you find it so?”

“No, sir; not at all. The work’s too hard. We’ve only got one foreigner in the place, and he ain’t an alien—he’s a Jap.”

“A Jap!” exclaimed Thorndyke. “Really. Now, I wonder if that would chance to be our old friend Kotei—you remember Kotei?” he added, turning to me.

“No, sir; this man’s name is Futashima. There was another Jap in the works, a chap named Itu, a pal of Futashima’s, but he’s left.”

“Ah! I don’t know either of them. By the way, usen’t there to be a cab-yard just about here?”

“There’s a yard up Rankin Street where they keep vans and one or two cabs. That chap Itu works there now. Taken to horseflesh. Drives a van sometimes. Queer start for a Jap.”

“Very.” Thorndyke thanked the man for his information, and we sauntered on towards Rankin Street. The yard was at this time nearly deserted, being occupied only by an ancient and crazy four-wheeler and a very shabby hansom.

“Curious old houses, these that back on to the yard,” said Thorndyke, strolling into the enclosure. “That timber gable, now,” pointing to a house, from a window of which a man was watching us suspiciously, “is quite an interesting survival.”

“What’s your business, mister?” demanded the man in a gruff tone.

“We are just having a look at these quaint old houses,” replied Thorndyke, edging towards the back of the hansom, and opening his pocket-book, as though to make a sketch.

“Well, you can see ’em from outside,” said the man.

Thorndyke’s strategy.

“So we can,” said Thorndyke suavely, “but not so well, you know.”

At this moment the pocket-book slipped from his hand and fell, scattering a number of loose papers about the ground under the hansom, and our friend at the window laughed joyously.

“No hurry,” murmured Thorndyke, as I stooped to help him to gather up the papers—which he did in the most surprisingly slow and clumsy manner. “It is fortunate that the ground is dry.” He stood up with the rescued papers in his hand, and, having scribbled down a brief note, slipped the book in his pocket.

“Now you’d better mizzle,” observed the man at the window.

“Thank you,” replied Thorndyke, “I think we had;” and, with a pleasant nod at the custodian, he proceeded to adopt the hospitable suggestion.

“Mr. Marchmont has been here, sir, with Inspector Badger and another gentleman,” said Polton, as we entered our chambers. “They said they would call again about five.”

“Then,” replied Thorndyke, “as it is now a quarter to five, there is just time for us to have a wash while you get the tea ready. The particles that float in the atmosphere of Limehouse are not all mother-of-pearl.”

Our visitors arrived punctually, the third gentleman being, as we had supposed, Mr. Solomon Löwe. Inspector Badger I had not seen before, and he now impressed me as showing a tendency to invert the significance of his own name by endeavouring to “draw” Thorndyke; in which, however, he was not brilliantly successful.

“I hope you are not going to disappoint Mr. Löwe, sir,” he commenced facetiously. “You have had a good look at that hat—we saw your marks on it—and he expects that you will be able to point us out the man, name and address all complete.” He grinned patronizingly at our unfortunate client, who was looking even more haggard and worn than he had been on the previous morning.

“Have you—have you made any—discovery?” Mr Löwe asked with pathetic eagerness.

“We examined the hat very carefully, and I think we have established a few facts of some interest.”

“Did your examination of the hat furnish any information as to the nature of the stolen property, sir?” inquired the humorous inspector.

Thorndyke turned to the officer with a face as expressionless as a wooden mask.

“We thought it possible,” said he, “that it might consist of works of Japanese art, such as netsukes, paintings, and such like.”

Mr. Löwe uttered an exclamation of delighted astonishment, and the facetiousness faded rather suddenly from the inspector’s countenance.

“I don’t know how you can have found out,” said he. “We have only known it half an hour ourselves, and the wire came direct from Florence to Scotland Yard.”

“Perhaps you can describe the thief to us,” said Mr. Löwe, in the same eager tone.

“I dare say the inspector can do that,” replied Thorndyke.

“Yes, I think so,” replied the officer. “He is a short strong man, with a dark complexion and hair turning grey. He has a very round head, and he is probably a workman engaged at some whiting or cement works. That is all we know; if you can tell us any more, sir, we shall be very glad to hear it.”

“I can only offer a few suggestions,” said Thorndyke, “but perhaps you may find them useful. For instance, at 13, Birket Street, Limehouse, there is living a Japanese gentleman named Futashima, who works at Badcomb and Martin’s mother-of-pearl factory. I think that if you were to call on him, and let him try on the hat that you have, it would probably fit him.”

The inspector scribbled ravenously in his notebook, and Mr. Marchmont—an old admirer of Thorndyke’s—leaned back in his chair, chuckling softly and rubbing his hands.

“Then,” continued my colleague, “there is in Rankin Street, Limehouse, a cab-yard, where another Japanese gentleman named Itu is employed. You might find out where Itu was the night before last; and if you should chance to see a hansom cab there—number 22,481—have a good look at it. In the frame of the number-plate you will find six small holes. Those holes may have held brads, and the brads may have held a false number card. At any rate, you might ascertain where that cab was at 11:30 the night before last. That is all I have to suggest.”

Mr. Löwe leaped from his chair. “Let us go—now—at once—there is no time to be lost. A thousand thanks to you, doctor—a thousand million thanks. Come!”

He seized the inspector by the arm and forcibly dragged him towards the door, and a few moments later we heard the footsteps of our visitors clattering down the stairs.

“It was not worth while to enter into explanations with them,” said Thorndyke, as the footsteps died away—“nor perhaps with you?”

“On the contrary,” I replied, “I am waiting to be fully enlightened.”

“Well, then, my inferences in this case were perfectly simple ones, drawn from well-known anthropological facts. The human race, as you know, is roughly divided into three groups—the black, the white, and the yellow races. But apart from the variable quality of colour, these races have certain fixed characteristics associated especially with the shape of the skull, of the eye- sockets, and the hair.

“Thus in the black races the skull is long and narrow, the eye-sockets are long and narrow, and the hair is flat and ribbonlike, and usually coiled up like a watch-spring. In the white races the skull is oval, the eye-sockets are oval, and the hair is slightly flattened or oval in section, and tends to be wavy; while in the yellow or Mongol races, the skull is short and round, the eye- sockets are short and round, and the hair is straight and circular in section. So that we have, in the black races, long skull, long orbits, flat hair; in the white races, oval skull, oval orbits, oval hair; and in the yellow races, round skull, round orbits, round hair.

“Now, in this case we had to deal with a very short round skull. But you cannot argue from races to individuals; there are many short-skulled Englishmen. But when I found, associated with that skull, hairs which were circular in section, it became practically certain that the individual was a Mongol of some kind. The mother-of-pearl dust and the granules of rice starch from the inside of the hat favoured this view, for the pearl-shell industry is specially connected with China and Japan, while starch granules from the hat of an Englishman would probably be wheat starch.

“Then as to the hair: it was, as I mentioned to you, circular in section, and of very large diameter. Now, I have examined many thousands of hairs, and the thickest that I have ever seen came from the heads of Japanese; but the hairs from this hat were as thick as any of them. But the hypothesis that the burglar was a Japanese received confirmation in various ways. Thus, he was short, though strong and active, and the Japanese are the shortest of the Mongol races, and very strong and active.

“Then his remarkable skill in handling the powerful caretaker—a retired police-sergeant—suggested the Japanese art of ju-jitsu, while the nature of the robbery was consistent with the value set by the Japanese on works of art. Finally, the fact that only a particular collection was taken, suggested a special, and probably national, character in the things stolen, while their portability—you will remember that goods of the value of from eight to twelve thousand pounds were taken away in two hand-packages—was much more consistent with Japanese than Chinese works, of which the latter tend rather to be bulky and ponderous. Still, it was nothing but a bare hypothesis until we had seen Futashima—and, indeed, is no more now. I may, after all, be entirely mistaken.”

He was not, however; and at this moment there reposes in my drawing-room an ancient netsuke, which came as a thankoffering from Mr. Isaac Löwe on the recovery of the booty from a back room in No. 13, Birket Street, Limehouse. The treasure, of course, was given in the first place to Thorndyke, but transferred by him to my wife on the pretence that but for my suggestion of shell-dust the robber would never have been traced. Which is, on the face of it, preposterous.