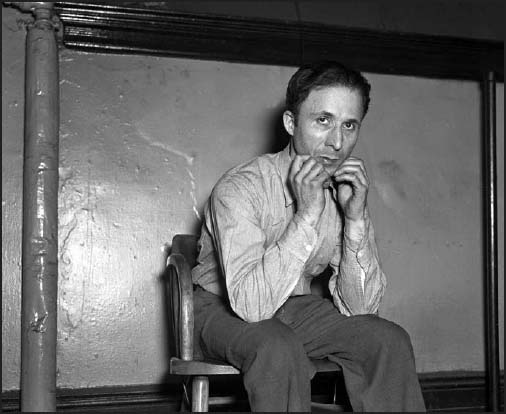

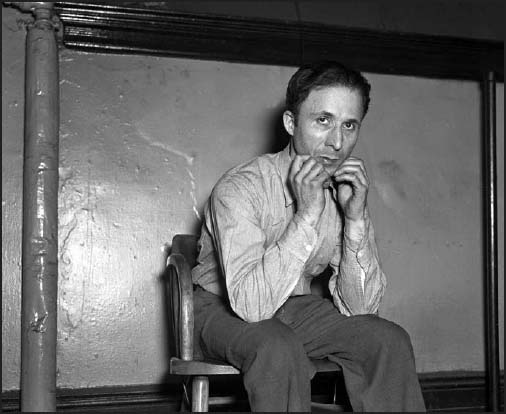

JOE HAD NO WAY of knowing how long he’d been sitting in the Hoboken jail. He was numb. What had happened? He had tried to help his family. Now he was in this dingy basement cell, waiting … waiting for something worse to take place. He couldn’t even turn around; the cell was as narrow as a coffin.1

He could barely focus. They had taken his glasses away. Was the old man going to die? That son of a bitch had insulted Anna, and now Joe had been charged with assault.2

He couldn’t think of what the police might do to him. Would he ever be able to see his wife and his children again? He sat in his cell and covered his face with his rough hands. What would become of Marie and little Joe? When he imagined his children’s upturned faces, he surely felt he’d be overcome by grief.3

But then he would have thought of Anna and grown calmer. Anna would do what she had to do to protect their children. Family was every-thing—a buffer against hardship, a leg up when needed. It could be a source of vindication, too, when that was called for. He’d known Anna ten years before they married, and this month they had celebrated their nine-year wedding anniversary. Anna would find a way.4

During the long Depression nightmare, he had seen how she could marshal her strength. She had certainly coped with their diminished income far better than Joe—probably because she had been poor before their marriage.5

Joseph Scutellaro in the Hoboken jail.

New York Daily News Archive/Getty Images.

One of eight children born to Italian immigrants, Anna Angelo had enjoyed the companionship of her many siblings and had also suffered with them when their longshoreman father, John, had fallen short on earnings.6 The older men downtown still spoke wistfully of the once-thriving wharves and industries of prewar Hoboken, but dock work had long been subject to the schedules of shipping companies and the whims of hiring bosses.

And even after John Angelo had turned to running a corner grocery, the family had struggled financially. To help make ends meet, one of Anna’s brothers, Christy, a chimney sweep during mild weather months, had worked for the Hoboken poormaster at Christmas. Christy Angelo knew Harry Barck as “a big politician” and the public face of city hall charity. Under Barck’s direction, he had distributed Christmas baskets to McFeely supporters who may or may not have been in need. Some people downtown grumbled that the city’s gifts of toys and candy were not really designed to help poor people anyway; the poor needed food or cash most of all.7

Anna remembered that Christy had asked Joe to join him in doling out Christmas baskets. This was before competition for city jobs—for any job—was so fierce. But Joe, she recalled, had vigorously declined to involve himself in “the vote-winning generosity of politicians.”8

It had been easy for Joe to say that then, when the Scutellaro family was flush. Unlike the Angelos, who, like other laborers across the country, routinely lacked steady employment, Joe and his father had enjoyed a certain employment security—or so they had thought.9

The Scutellaros’ financial descent—first with the loss of city jobs, then with the loss of all jobs—had been unexpected and, for the family patriarch, uncharacteristically humbling. Now in his sixty-fourth year, Frank Scutellaro had spent most of the preceding fifty vigorously establishing himself as an accomplished carpenter and contractor. He had been so driven, so intent upon advancement, that even on his wedding day in 1901, he had left for a job right after the celebration ended, peddling away on his bicycle. The twenty-seven-year-old groom’s single-mindedness had likely bewildered his nineteen-year-old bride, Marie Thomas, but she had been smitten by the handsome, ambitious carpenter—as many women had been. Frank Scutellaro had been quite the ladies’ man and an all-around charmer. And Marie, a Hobokenite by way of Alsace-Lorraine (she had left Europe at age four) must have sensed that his charisma and tenacity, combined with his carpentry skills, would help him succeed in a city with so many hungry workmen.10

In the years that followed, Frank Scutellaro could boast—and he did—that he’d made a good life for his family. But building it hadn’t been easy. When he was a teenager arriving in the United States, Italian immigrants had faced vicious bigotry. For some their harassment had begun as soon as they’d debarked at the Hoboken pier. German dock-men had shouted ethnic slurs at the swarthy, dark-haired strangers and had set upon them with sticks.11

But the men who had left their native villages had been desperate for jobs. Unlike Frank, who arrived as a trained artisan, many had disembarked with only their strong backs to sell. They settled in Hoboken for the work the city offered. Though the labor they were hired to do was arduous and often dangerous, and Italian workers were subjected to abuse by Irish foremen, at least they had work.12

For every other necessity, the new arrivals had drawn upon the Old World. They had re-created societies and feasts to honor the saints that had so ably protected their towns on the other side. The faithful marched through the downtown streets carrying ornately ornamented banners and jewelry-clad statues; and behind them, clusters of children followed, eager to hear the sizzle and rapid-fire pops of fireworks that punctuated the marchers’ path. When the weather was good, many gathered behind their tenements to celebrate. A backyard strip of dirt or poured cement—already narrowed by the installation of a henhouse or a grapevine—could be outfitted with a long communal table, around which family and friends would gather to eat a meal prepared in the tradition of the host’s native province, and homemade wine was sure to inspire jubilant music.13

In those prewar years, the Scutellaro household had cause to celebrate. A year after they were married, Frank and Marie became parents. They would have been very unusual indeed, if they had doubted that their American-born son, whom they named Joseph, would inherit and build upon the success of his immigrant father—a prospect that became an imperative after Marie’s later pregnancies failed.

Joe’s position as an only child was sufficient to set him apart from his schoolmates, who mostly lived in homes crowded with siblings, but his increasingly prosperous parents had also spoiled him. After she knew she was going to marry him, Anna informed Joe that when she’d first seen him around town, she thought he was a show-off, with his new clothes and nice things. Not until they’d begun dating did she realize that Joe was unpretentious and even a little timid—nothing like his self-important father.14

Frank had become well known downtown, and he’d enjoyed his elevated stature. Never one to be shy, he’d been especially fond of grand public gestures. If something was going on in town, if the local Democrats were sponsoring an event, Frank Scutellaro wouldn’t buy two or three tickets—he would buy a hundred. He was out to make an impression.

Over the next twenty-odd years, Frank bought and built properties, proudly showing off his series of brick apartment buildings and making neighbors aware of his string of west-side garages. The Scutellaros could now afford luxuries that many in the city could barely imagine. When Joe, just out of his teens, seemed tubercular and in need of a health retreat, Frank sent him to a resort in Pinehurst, North Carolina, where his recuperation included playing rounds of golf. And soon after, Joe became one of the first young men in town to have his own automobile—a gift from his father.

Joe’s car might have added to Anna’s perception that he was a showoff, but in the end, the car had helped him win her. The small parlor over the Angelos’ corner store had been filled with suitors drawn to Anna’s sunny nature and her splendid night-black hair. Joe gained a place in Anna’s affections when he offered to take her infirm mother along with them on a drive—and then continued to ferry them to the countryside, after seeing how deeply the older woman enjoyed the views beyond her apartment window.

When they were alone, the smitten young man, who rarely spoke while in the Angelos’ crowded apartment, would serenade Anna, singing in a clear and melodious voice Neapolitan love songs, tunes from popular American films, and German songs he’d picked up from his multilingual mother. And though a mutual friend had introduced Joe to Anna as “Harold Lloyd”—a reference to his striking resemblance to the handsome, dark-haired, bespectacled 1920s comedic film star—the man Anna fell in love with was not the go-getting character Lloyd most famously portrayed. No, Anna Angelo fell in love with a man who was mostly out of step with the noisy, frenetic, Jazz Age strivers; Joe Scutellaro was quiet and gentlemanly and—she would have had to admit—coddled. He had won her first with his slow, one-sided smile and then with his nearly desperate love. For Joe’s proposal of marriage to Anna had had great force, coming from one so often silent. He had cried out to her that he could not live without her and could not bear the thought of her with another.15

As he sat in the cold Hoboken jail, Joe would have pictured Anna and their children. Every day, before he’d set out to search for work and the day’s meager rations, he had drawn them close. He had noted his tiny son’s pallor. When he bowed to kiss Marie, she would scan his face and offer a small, hopeful smile—a gesture both uplifting and heartbreaking. Each day he would leave the apartment with them in mind, as if they were accompanying him on his anxious rounds.16

Along with his son and daughter, perhaps, there had been the specters of other children. For following reports of children dying of starvation in faraway cities like Oakland, California, and even across the river in seemingly distant New York City, had come terrifying local news that would have haunted Joe Scutellaro: a little boy named Donald Hastie had starved to death in Hoboken after his parents had been denied more relief by Poormaster Harry Barck.17

“Three-year-old Donald Hastie died of starvation at 9 o’clock yesterday morning at St. Mary’s Hospital, Hoboken,” the Hudson Dispatch declared on July 15, 1936, three months after the federal government, and then the state of New Jersey, had withdrawn from emergency poor relief and left Harry Barck in charge. By then the city’s poor would have been unlikely to afford a daily newspaper, but with vendors hawking tabloids on the street, most would have seen the startling headline and the accompanying photograph of the boy’s hollowed parents mourning beside a small white coffin.18

It would have been a difficult picture to forget.

The image would have instilled in Hoboken parents fear for the future of their children. For Joe and Anna Scutellaro, it surely stoked worries they already had. Their son, Joseph Jr.—born just a few months prior to Donald Hastie’s wasting death—was terribly small and frail.19

Word of the local boy’s starvation and his parents’ protracted struggle to keep him alive had spread quickly in Hoboken. The poorest families would have heard about the state of Donald’s body—”mere skin and bones,” according to one observer—and eyed their sons and daughters with alarm. For the Hasties’ story was all too familiar. Poormaster Barck had made the main breadwinner, thirty-five-year-old James, scurry for aid, and when it was finally granted, the unemployed father of three had received $5.40 in a biweekly check, or thirty-eight cents a day, to feed five people.20

The Hasties had left Scotland just before the onset of the Depression, hoping for a better future for their children in the United States. By 1936, faced with massive unemployment in their new location and lacking any relatives nearby, they sought simply to sustain themselves. James had begged the poormaster to approve more aid, so he could buy milk for his boys—eleven-year-old Jimmy, three-year-old Donald, and baby John, just over a year old. But Harry Barck had upbraided him for his audacity. “He told me I was no better than anyone else, that there was no money for ‘extras,’ and that I should be glad to get as much as I was getting,” James would later recall, adding that Barck “told me there were plenty of jobs if I would look for them.”21

After her son’s death, thirty-two-year-old Margaret Hastie said she prayed her family’s loss might bring about a change in the way relief was handled in Hoboken, “so that other babies of the unemployed will not go hungry or die like Donald.” She did not want his passing to be put down to hard luck or neglectful parenting. Nor would she stand for later attempts by the city to obscure the cause of her child’s death.22

Margaret told whoever would listen that two days before he died, Donald had been taken by ambulance from their first-floor Willow Avenue apartment to be treated for malnutrition in Hoboken’s St. Mary Hospital. City funds supported the hospital’s care for the destitute. Donald’s undernourished state was recorded in the police blotter, and, after an examination, a hospital intern noted the same condition.23

But after Donald died and Margaret viewed his death certificate, she discovered that another doctor at the hospital had cited “lead poisoning” as the cause of death. And though the hospital was required to report the death and its cause to the county, the county physician did not learn of Donald’s passing until contacted by a newspaper reporter.24

Margaret and James acknowledged that they had seen Donald eating chips of dried paint, peeled from the walls of their threadbare apartment, and they had tried repeatedly to stop him. But he had continued to do so, they asserted, to satisfy his unyielding hunger. “Donald often cried for milk and complained of being hungry,” Margaret Hastie said. “I would explain to him that we had no money for milk.” She protested that her son’s death had been from starvation and requested an autopsy.

Her appeal went unfulfilled. The doctor who signed the death certificate professed to newsmen that the undertaker had somehow claimed Donald’s body before a necropsy could be conducted. Nevertheless, he went on to assure them, the hospital had made X-rays and “other tests” to determine that the child’s death was “definitely” the result of lead poisoning.25

The night the doctor issued Donald’s death certificate, his parents held his wake in their front parlor. Neighbors helped with funeral expenses despite their own strained budgets. One contributed a suit for the boy’s burial. Others paid for sprays of white flowers, the hearse rental, and the cost of two professional pallbearers to carry the coffin from the home to the funeral car. They even paid the Hasties’ electric bill, so the tiny casket—donated by a local funeral director and opened to display Donald’s body—would not sit in the dark, as the family had for so many weeks before.26

No city officials attended the wake. Mayor Bernard McFeely was not available for interview at his office, and when a Dispatch reporter reached him by telephone at his home and asked if he intended to investigate the death, the mayor replied, “I have no comment to make at this time.”27

The reporter had pressed again. “Do you intend to check up on the relief situation to determine whether there are other cases like the Hastie case?” he asked.

“I have no comment to make at this time,” responded the mayor.

The poormaster was, at first, said to be “bewildered by the developments,” but his later published remarks were cool and unsentimental. Harry Barck informed a reporter that, regarding Donald Hastie, his conscience was clear. He had done all he could, he said, including making an offer to have his office pay for the child’s burial in the potter’s field, which the family had refused.28

On the morning of July 16, the Hasties, a few parishioners from the First Baptist Church, and its young minister, Reverend C. Robert Pedersen, assembled around Donald’s coffin for a brief home service before making the journey to Hoboken Cemetery. Margaret Hastie wailed as she viewed her child for the last time. A friend held her tightly, gripping one of her spindly wrists to keep her from tearing at her hair.29

Hundreds of the Hasties’ neighbors had gathered at the family’s Willow Avenue tenement. They crowded the room adjoining the parlor, packed the hallway and stairs, and spilled over into the street. Four policemen were posted at the address to keep clear an aisle for the pallbearers and mourners to accompany the coffin out of the building.

Newspapermen arrived in force, too. Hoboken’s more comfortable residents, the ones who could yet afford their daily newspapers and adequate food and who might have continued to believe that the poor were responsible for their own suffering, would now be faced with a damning account of the failure of the relief system.

The story would extend to readers well beyond Hoboken’s borders, including state lawmakers. More than a dozen journalists covered the boy’s funeral, and just as many photographers perched on fire escapes to best capture the developing scene. “Widespread publicity has been given the case,” one reporter commented, “and from its repercussions and the welter of conflicting opinions attending it, there has been sounded a note of its possible use as a political issue, involving the question of whether relief administration may be best handled by the state or by municipalities.”30

The state did initiate an inquiry into the “deplorable conditions in Hoboken.” But when their findings were made public sixteen months later, in January 1938, state investigators, who established that “abominable treatment” of relief clients had been combined with expenditures far below those in cities of comparable size, concluded only with a rebuke that Barck’s office had failed to meet adequate relief standards. There was to be no state takeover.31

“We did all we humanly could … ,” a state official charged with overseeing relief standards later declared, “but we cannot go into a municipality and dictate. We have no police powers and can only tell them what we think they should do in maintaining relief standards.” Under the law, he explained, “… administration is a local matter, with the state only an indirect supervisor. We make our investigations, and do what we can, but the matter of who gets relief and how much is up to the local overseers.”32 Mayor McFeely, who could have removed Barck from his appointed post, made no changes and issued no statements reproaching his overseer. Harry Barck remained in power for a few weeks after the state shrugged off responsibility for Hoboken’s poor. Then came the fatal altercation with Joe Scutellaro on February 25.