12

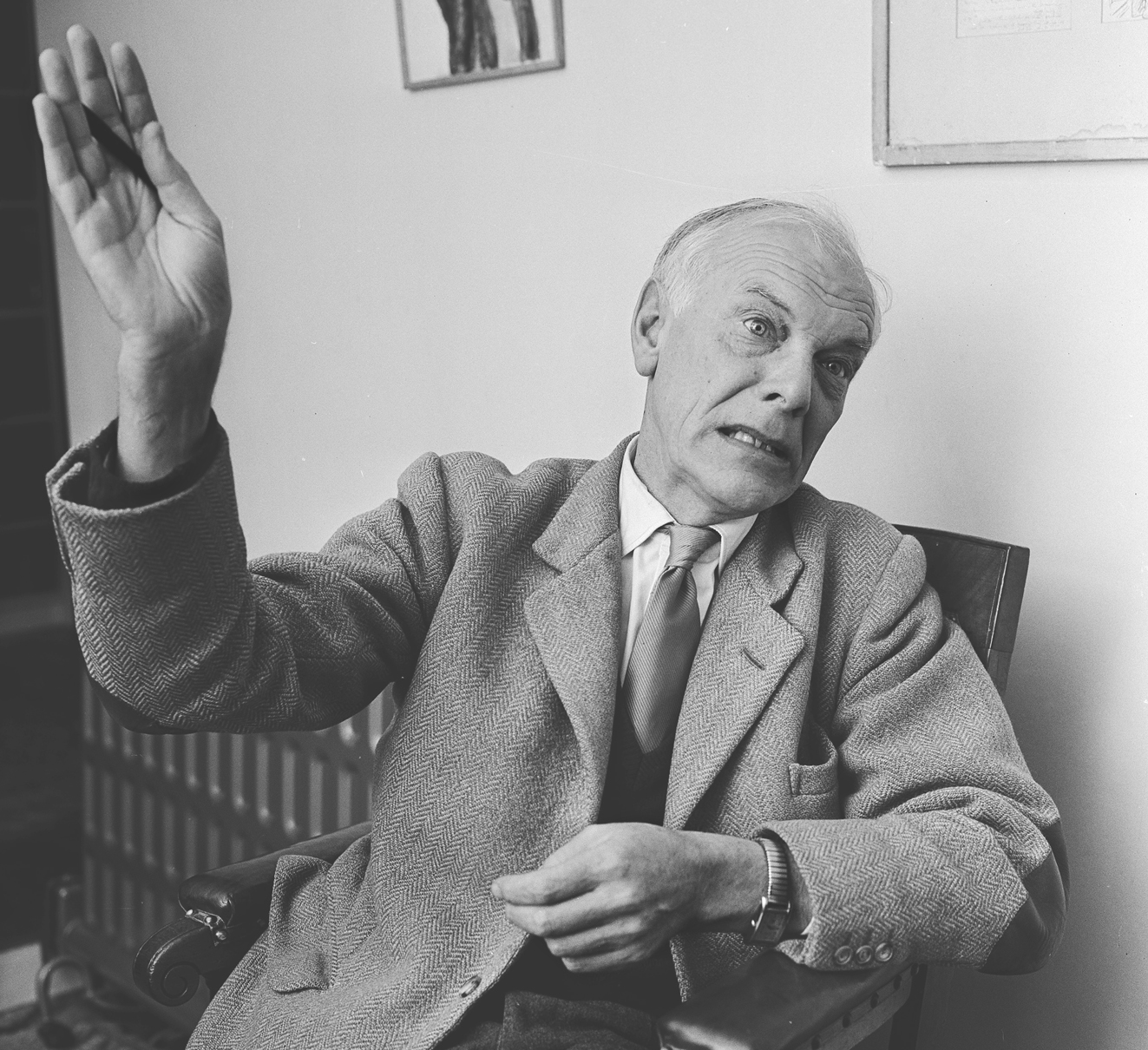

Already well-known as a journalist and editor, and rapidly becoming a household name as a television presenter, Malcolm Muggeridge took a flight from London to Hamburg on 7 June 1961. Two months earlier, he had recorded his distaste for the medium with which he would soon be identified.

As always deeply distressed by seeing myself on television … Decided never to do it again. Something inferior, cheap, horrible about television as such: it’s a prism through which words pass, energies distorted, false. The exact converse of what is commonly believed – not a searcher out of truth and sincerity, but rather only lies and insincerity will register on it.

Having visited the offices of Stern magazine, Muggeridge went out on the town. True to character, he took relish in finding it ‘singularly joyless; Germans with stony faces wandering up and down, uniformed touts offering total nakedness, three Negresses and other attractions, including female wrestlers. Not many takers, it seemed, on a warm Tuesday evening.’

Popperfoto/Getty Images

On a whim, he dropped into the Top Ten Club on the Reeperbahn, ‘a teenage rock-and-roll joint’. A band was playing: ‘ageless children, sexes indistinguishable, tight-trousered, stamping about, only the smell of sweat intimating animality’. They turned out to be English, and from Liverpool: ‘Long-haired; weird feminine faces; bashing their instruments, and emitting nerveless sounds into microphones.’

As they came offstage, they recognised Muggeridge from the television, and started talking to him. One of them asked him if it was true he was a Communist. No, he replied; he was just in opposition. ‘He nodded understandingly,’ observed Muggeridge, ‘in opposition himself in a way.’

‘“You make money out of it?” he went on. I admitted that this was so. He, too, made money. He hoped to take back £200 to Liverpool.’

They parted on good terms. ‘In conversation rather touching in a way,’ Muggeridge recorded in his diary, ‘their faces like Renaissance carvings of saints or Blessed Virgins.’