2 The Dialectic of Landscape in Italian Popular Melodrama

In his book on landscape painting, Political Landscape, Martin Warnke briefly discusses the derivation of his title, a term that he assumed had a long history.1 Instead, he discovered that the phrase was coined only in 1849, and then in relation to a landscape painting that quite literally described a political, rather than a pastoral, landscape. Its first use as a description of the terrain of a national politics was by Joseph Goebbels, who criticized a film for not being fascist enough for the German political landscape. This discovery alarms Warnke, and he rapidly returns to the painting, using this earlier and safer version to justify his book’s title. But these two origins are more suggestive of the relationship between politics and visual representations of landscape than Warnke’s brief discussion would imply.

There is, first of all, an unremarked connection between these deployments of the term: in each case, what is being discussed is not any actual political situation but a visual text—first a painting and then a film. Landscape, after all, is a visual concept. But there is equally a difference in their deployments insofar as there is a switch in the levels of metaphor between the two uses of the phrase. In 1849 the landscape has a material existence, and politics is the metaphor employed to explain the image; by the 1940s real politics are at stake, and landscape is the metaphor evoked to explain them. This latter meaning has become the dominant one: has become, perhaps, a figurative cliché by which politics as a field is conjured rhetorically. It is telling, therefore, that Warnke would be determined simultaneously to retain his title and to disavow its more substantive origin. It is understandable, of course, to want to avoid using a Nazi turn of phrase, but the origin of the term in Nazi Germany, and its close connection to images, underwrites a nexus of meanings around landscapes, representation, and politics that is both potent in postwar European culture and inevitably tinged with suspicion.

The spatializing rhetoric of the “political landscape” condenses what Walter Benjamin called the aestheticization of politics in fascism2 at the same time as it hints at landscape as nationally charged space, with all the overtones that the materiality of European land implied during World War II. And yet despite, or perhaps because of, this rhetoric, landscape has figured frequently in postwar visual culture in Europe, especially in cinema, and often with a quite different political valence. We could point to Italian neorealism as a key countering discourse, where images of landscape such as those in Roberto Rossellini’s Paisà (1946) are deployed precisely as an anti-fascist strategy, making a claim for landscape’s contribution to a progressive politics, resignifying European space. By the 1990s, however, the perceived spectacularization of politics in the mass media formed part of a renewed anxiety around the politics of the spectacular image, an anxiety manifested in relation to cinema with the Marxist critique of a postmodern culture of surface and image. Because landscape images form an important part of contemporary European cinema’s emphasis on mise-en-scène and visual pleasure, they have become central to this critique (think of the critical response to the widescreen vistas of The English Patient [Minghella, 1996]).3

In the context of post-Wall European cinema, however, when the physical space of Europe was once again politically central, it becomes crucial to interrogate the geographical, historical, and ideological stakes of any claim to visualize national landscapes. These images tap into a powerful nexus of ideas about European identities and cannot simply be dismissed as postmodern eye candy. In fact, I would suggest that landscape images in film are uniquely able to investigate this relationship of politics, representation, and history because landscape as a mode of spectacle provokes questions of national identity, the material space of the profilmic, and the historicity of the image. By examining a group of Italian films that narrativize postwar national histories in the context of spectacular and visually pleasurable locations, I want to think about the specificity of landscape images in cinematic terms: to read mise-en-scène as an ideological articulation of space and as a political landscape that invokes a particularly European formulation of history.

Italian Heritage

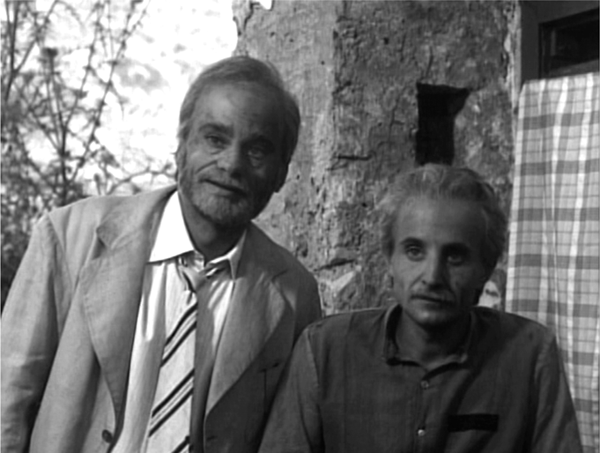

Cinema Paradiso, Mediterraneo, and Il Postino appear to be readily categorizable as a group of related films, a strand within a historically specific cinematic practice. All three are set from near the end of World War II to the early 1950s; or, rather, they are principally set at this time, for all three also have a narrative coda at a later date, usually in the present. All three have as protagonists young Italian men or boys growing to manhood in the postwar Italian context, and all are structured by a melodramatic romance narrative. Cinema Paradiso tells the story of Totò, from his movie-obsessed childhood in Sicily, through a doomed first love affair, to a present-day career as a film director in Rome. In the lengthy first section of the film, Totò forms a bond with Alfredo, the projectionist at his local cinema, and the film’s melodrama deals with both this friendship and his romantic relationship with Elena. Similarly, Il Postino narrates hero Mario’s relationship with the poet Pablo Neruda, as well as his romance with Beatrice. Mario is the postman who brings Neruda’s mail during his exile in Italy, and the poet teaches Mario lessons in political awareness as well as in seduction. Mediterraneo takes place on a Greek island, where a group of Italian soldiers spend the war largely untouched by battle. The protagonist, Farina, falls in love with local prostitute Vassilissa and decides to stay in Greece when the war is over. Farina’s captain, like Pablo Neruda and Totò, ends the movie looking back on the postwar years from the present day.

In addition to these narrative similarities, all three films became immensely successful in the global market, most strikingly in the United States, where all were nominated for Oscars and were in the 1990s in the top ten foreign-language films in terms of box office grosses. In addition, all three films did well in Italy itself (although Cinema Paradiso was not popular immediately) and can be seen as key texts in an early 1990s renaissance in domestic film consumption that was in part jump-started by Cinema Paradiso’s success at the Cannes Film Festival (where the film won the Special Grand Jury Prize) and in the United States (where it won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film). And in the context of contemporary European film production, all three can be typed as heritage cinema, a genre characterized in part by elements of melodrama, historical narrative, and international distribution alongside a mise-en-scène of national nostalgia.4 As such, these films form a useful case study for looking at the workings of the heritage film in terms of its historicity and spectacle. However, the films are also fine examples of the problems inherent in using the “heritage” tag, for the heritage film is very much a generic mix—a complex amalgam of various genres, forms, and industrial factors. The apparent obviousness of the European heritage film, to both popular critics and academics, has prevented the kind of close analysis of individual films that is necessary for a more nuanced theorization of the category. The vagueness of the heritage category certainly produces as many problems as it solves for placing these Italian films.

Andrew Higson describes the genre as a middle-class product, “somewhere between the art house and the mainstream,”5 and thus far at least, his definition is applicable. Indeed, this formulation points to the historical specificity of such films, coming as they do at the moment in which such a blurring of the boundary between art cinema and mainstream cinema is not only possible but, for the beleaguered European film industries, economically necessary. European coproductions, and the rise of television funding for feature films in the 1980s through channels like Channel 4 in the United Kingdom, France Télévision 1 (TF1) in France, and Zweiten Deutschen Fernsehen (ZDF) in Germany, helped sustain a more commercial European mode of film production and exhibition, but they did so in a way that produced a redefinition of “art house” or art cinema, a shift toward films that could remain conceptually distinct from American higher-budget genre films but would have the potential for a wider distribution than an earlier form of modernist European art film. Cinema Paradiso and its successors fit into this rubric exactly, certainly in terms of their structures of production, distribution, and exhibition. Cinema Paradiso was coproduced by, among others, Radiotelevisione Italiana (RAI), the Italian state television network, and the production arm of the French channel TF1, while Il Postino was produced by a combination of Italian film production companies and Le Studio Canal Plus in France. To categorize the films through this mode of production is useful to the extent that many foreign films are circulated predominantly through this kind of branding process. All three films were released in the United States by Miramax and, at least in the United States, are recognizable as what has become known popularly as a “Miramax” kind of film: culturally respectable, while not overly demanding; more widely distributed than is common for foreign films; and often nominated for major awards.

While there may be significant overlap between the kinds of film production enabled by the new European coproduction bodies and what Higson means by heritage film, they are not quite coterminous. Higson describes heritage films as “quality costume drama,”6 a definition that makes perfect sense in regard to his examples of Merchant Ivory films set in Edwardian England or colonial India but sits uneasily with Italian films set in 1945 or later. Can a film set after World War II really count as a costume drama? This question perhaps shows up the uncomfortable fit between these Italian films and the heritage category, but it reveals further the difficulty of fitting this kind of historical film into any single genre. They feature narratives set in the past but are certainly not history films in the usual sense of relating historically significant stories of famous events or personalities. And while they have melodramatic elements, they are set rather too recently to include many of the pleasures that Sue Harper talks about with reference to costume drama and its historical mise-en-scène.7 They could be placed as period dramas, perhaps, although while this category is too vague to exclude any film with a historical setting, it connotes a more distant, more exotic, period of representation. Nor are they films in any other established genre that allows for narratives set in the past—they are not, for example, historically located gangster films such as Miller’s Crossing (Coen, 1990) and The Krays (Medak, 1990).

Outside their historical settings, we could consider them in terms of more broad cinematic genres, but again the films turn out to be hybrids. Certainly, the narratives include many melodramatic elements; I will discuss the effects of these structures in more detail later, but for now it is enough to note the films’ concentration on romance plots and their concern with affect. In all cases, the narrative operates to produce tears in the spectator. And yet, despite being based on narratives that are characteristic of women’s films, or perhaps their contemporary equivalent, “chick flicks,” they do not revolve around female protagonists, but young men, and tend to produce a wholly masculine subject position. Even generically, the melodramatic plot is undercut somewhat: in Mediterraneo, for example, the love story is embedded in both a war setting and a comedy. In addition, the “between art house and mainstream” structure that Higson points out clearly involves some elements of art cinema; the films are slow moving on occasion and more concerned with mise-en-scène and the pleasures of spectacle than is conventional in Hollywood melodrama. Characterization often takes precedence over narrative, and discourses of quality attend the historical and national cultural elements of narrative.

Higson himself discusses the difficulty of using heritage film as a genre, certainly as a coherent one, pointing out that because the category was largely invented by critics rather than either producers or audiences, and intended frequently as a negative criticism, it becomes something of a self-fulfilling prophecy. Only the bourgeois and conservative historical films are called heritage films, and so the category comes to seem defined by this critique. He suggests expanding the genre to include films set in the recent past and featuring working-class characters—such as Backbeat (Softley, 1994) and Distant Voices, Still Lives—and to include many European and, indeed, world examples. I am interested in his attempt to expand the genre insofar as it enables more room to rethink the terms of the heritage debate, which, certainly in reference to British films, had become somewhat stale. And it is certainly productive to compare, say, Cinema Paradiso with the films of Terence Davies, with which it has substantially more in common than with more conventional heritage films like A Room with a View. But what seems more productive than the addition of some less conservative films is to open out the terms of those critiques to inspection, to consider how and why we criticize heritage films, and to use these issues to approach the Italian films.

The first set of words commonly employed to critique heritage films are “sentiment,” “melodrama,” and “nostalgia.” When Cinema Paradiso topped a British newspaper poll of the best films of the 1980s, reviewers expressed surprise that such a sentimental film should be so popular with British audiences. One reviewer argued: “It seems that the golden-hued air of dreamy nostalgia placed in a Mediterranean setting, complete with shouting peasants, doe-eyed bambini, funny fascists, village idiots and the Araldite bonding of traditional family life, avoids all the baggage which a more explicitly British treatment inevitably brings on board—Victorian repression, twilight-of-Empire anguish, class struggle and greyness.”8 A similar review of Il Postino called the film a “lazily predictable tale of Mediterranean backwardness, stocked with cliché characters—local fisherman, smouldering dark beauty … black-clad widow, seedy politician, anti-Communist local priest … and helped along with sentimental detail.”9 And, again, with Mediterraneo: “It rests too comfortably for its own good on a string of clichés: loveable, incompetent Italian soldiers … thieving Turks … a buxom whore with a heart, and any amount of balmy evenings of hard drinking and soft landings.”10 The complaints of clichéd character types and sentimentality imply a melodramatic rather than a realist historical narrative, and reviews in other countries reiterated the same terms of description.11 The recurring complaints, then, are of sentiment, nostalgia, sloppy or whitewashed history, a touristic view of the region, and a reactionary political slant—all the same criticisms, more or less, that are made by academic critics of heritage films.12

One particularly pointed example of a related scholarly critique is Susannah Radstone’s discussion of Cinema Paradiso,13 which is useful in this context not only because these films have rarely been analyzed in any theoretical depth but also because she addresses several issues that will become of central importance to my argument. Like the journalistic critics, Radstone argues that the film is nostalgic and hence has no genuine engagement with history. Using Fredric Jameson’s concept of “history/nostalgia,”14 part of his discussion of postmodern history films and the retro mode, she accuses the film of rejecting any social critique or historical friction in favor of the easier pleasures of an airbrushed myth of a collective memory, a pastiche of history. For Radstone, the film is neither personal nor social but, rather, exemplifies a structurally regressive strategy that is characteristic of the patriarchal and ahistorical tendencies in postmodernity—what she calls “turning everything into an exhibit.”15

Her analytical focus here is on the films shown within the film, the many clips seen by Totò at the Paradiso, which come to define both his cultural memory and that of the nostalgic spectator. For Radstone, these sequences give the lie to the film’s claims of representing an individual memory, as they are recognizable and conventional clips from a canonical history of film—examples include La terra trema (Visconti, 1948) and The Lower Depths (Renoir, 1936). In their sameness and connection to a meditated narrative of history, they conflate the personal with the social in a way that is reactionary.16 I will return to the question of the films within the film, but what is particularly suggestive for us here is Radstone’s reading of this historicity through both Jameson’s argument on postmodern nostalgia and Benjamin’s concept of Erfahrung. For Radstone, these nostalgic film clips are the opposite of Benjamin’s theory of experience, and in falling into the less radical Erlebnis can be read not only as postmodern nostalgia but as a metadiscursive histoire, lacking the connective power of storytelling.17 Thus, Radstone extends the debate around nostalgia and historical memory, connecting these questions both to Benjamin’s theorizations of experience and to a historically specific debate around contemporary film form.

The second critique of this kind of historical text is inherent in the debate over heritage film itself, for, Higson’s self-awareness notwithstanding, the concept is defined almost purely through the deployment of a negative defining move.18 This move involves several levels of critical attack: at the level of extratextual history, at the level of narrative, and, most important, at the level of the image. The extratextual and narrative criticisms are linked, in an argument that the films fail to engage with contemporary politics and use historical settings as a way to avoid pressing issues of representation. Higson thus claims that the heritage film grew in the 1980s alongside more multicultural societies in Europe and so allowed the predominantly middle-class white audience to reenter a disappearing world of unchallenged white privilege.19 As a corollary to this historical case is the narrative argument that the films fail to engage with current social issues within their diegeses; they ignore marginal groups and do not offer, as more political films might, realist engagements with social realities.20

Most problematic for Higson, though, is the ideological effect of the image in heritage films, which he argues deploys an excessively pictorial and decorated mise-en-scène in a way that undercuts any political promise that the narratives might otherwise have contained: “Even those films that develop an ironic narrative of the past end up celebrating and legitimating the spectacle of one class and one cultural tradition and identity at the expense of others through the discourse of authenticity and the obsession with the visual splendours of period detail.”21 For example, in Howards End (Ivory, 1992), the narrative may valorize the newly created bourgeoisie or the bohemian Schlegel family, but the lengthy shots of plush interiors cannot help but privilege the aristocracy. A large part of this impulse, of course, is specific to British heritage films and to the mise-en-scènes of a class system based on property and land ownership. Richard Dyer implies as much in his discussion of heritage films in terms of a museum aesthetic and as heritage attractions.22 The attractions he is referring to are country houses, themselves on display in reality as a part of the tourist industry. But Higson’s argument, although it derives from the British films in which this critique has a specific object, is wider than Dyer’s and attempts to problematize mise-en-scène in heritage films in general. Thus, “the image of the past in heritage films has become so naturalised that, paradoxically, it stands removed from history: the evocation of pastness is accomplished by a look, a style, the loving recreation of period details—not by any critical historical perspective…. They render history as spectacle, as separate from the viewer in the present.”23 Or, more succinctly: “The pleasures of pictorialism thus block the radical intentions of the narrative.”24

This key critique makes explicit what is implicit in many of the other arguments against heritage history films: the sense of anxiety around the image and around the spectacular image as historical. This anxiety surfaces across theories of the heritage film, as well as in Radstone’s connection of heritage to retro postmodernism. I will return to this anxiety and will take issue with Higson’s ideological reading of the image and with Radstone’s use of Jameson and, more particularly, of Benjamin. However, I will begin with the question of narrative and consider in more detail how Il Postino, Mediterraneo, and Cinema Paradiso can be read as nostalgic and melodramatic. Rather than stopping with these terms as epithets of self-evident critique, it is necessary to examine both the films and their historical context in some depth in order to interrogate the significance of these narrative structures.

Italy Postwar: What Went Wrong?

Earlier, I quoted a magazine review in which Cinema Paradiso is criticized for showing “funny fascists”25—in other words, for failing to represent the seriousness of fascism. In light of discussions around such films as Life Is Beautiful, such a complaint is perhaps timely, but I bring it up again not for this ethical debate but to point out that it is, simply, historically wrong. There are no fascists in Cinema Paradiso, funny or otherwise, because the narrative takes place after World War II is over, or, at the very earliest, it begins in the closing months of the conflict in 1945. And, as the film is set in Sicily, which was liberated in 1943, this slight uncertainty is irrelevant as far as a fascist presence goes. It need hardly be said that my reason for uncovering this mistake is neither to discredit the reviewer nor to spot the kind of nit-picking historical glitches that spectators of historical films are traditionally fond of discovering. Failure to notice the end of World War II does seem to be somewhat more than a glitch, but the significance of this slip is not limited to the accuracy of the review. Instead, I would like to suggest that this blunder is symptomatic of a larger problem with the way these films are read: with a lack of attention to Italian political and cinematic history, which, in turn, facilitates claims of historical emptiness such as Radstone’s and enables critics to dispose of the films as apolitical. It becomes easier to dismiss a text as historically empty when the history at stake is misread or ignored. This is not an empiricist claim on historical knowledge or textual accuracy but a methodological question with a direct influence on how we can theorize the operation of historicity in these texts.

The misreading is a simple one and is contained both in Peter Aspden’s ignorance of the Italian postwar situation and in his presumption that the site of historical engagement (and its potential problems) must be fascism. There is a sense that for Italy only a discussion of the years of fascism or war can count as truly facing up to the past and that a choice of subject that postdates fascism by such a short period is, inevitably, evading the issue.26 This sense is compounded by a comparison with Italian art films of the 1960s and 1970s, when representations of fascism were a common topic, taken on by many of the most internationally lauded auteurs. Examples include The Conformist, Amarcord (Fellini, 1973), and Christ Stopped at Eboli (Rosi, 1979). Thus, just as 1980s and 1990s films are disadvantageously compared with the art house films of the decades before in terms of aesthetics, so they are easily considered at best less serious and at worst reactionary in their politics. If a history film is apolitical, then the symptom of this will be a lack of fascists (or only “funny” ones), and a lack of fascists can correspondingly signify only a lack of political engagement.

Such an interpretation fails to consider the political significance of the years immediately following the end of World War II in Italy, where from 1945 to 1948 a struggle took place over how Italian national identity would be remade, concluding with the formation of the First Republic and the installation of a party system that remained in power for fifty years. The breakup of the unified anti-Fascist Resistance (CNL), the defeat of the Italian Communist Party (PCI), and the victory of the rightist Christian Democrats (DC) speak of a moment that is far from safe historical territory for Italians, but is in fact more fraught than a reiteration of a fascism that all can agree on condemning. And while fascism may have been a crucial topic in the 1960s and 1970s, when the war was first being reconsidered in European culture at large, the years 1945 to 1948 became an equally compelling topic in the early 1990s, when the postwar republic came under increasing pressure and finally, in 1992, collapsed altogether.

For the Italian Left, the key historical question of the 1990s was not How did we allow fascism to happen? but What went wrong after the war? The long partition of Italy between 1943 and 1945 produced a strong partisan coalition that, by the end of the war, was already part of a national debate on the future government of the country. And when the Communist leader Palmiro Togliatti returned to Italy from exile in the Soviet Union with a new plan for the transformation of the PCI into a democratic socialist party, that debate was directed toward a wholesale rethinking of the role of the Left in the new order.27 Of course, the country was in a precarious condition, and the legacy of fascism was hardly dismissed, but nonetheless, as Elizabeth Wiskemann puts it, “there was a tremendous feeling of national exhilaration. This had been a second Risorgimento, the Italians felt, a more real one in which all classes had participated.”28 As the new constitution was drawn up in 1946, there was a moment of unique possibility, in which political parties were being created anew, and to speak of an entirely new nation appeared to be no exaggeration. This exhilaration was most evident in the Left, which, as the mainstay of the Resistance, had pushed successfully for a Left-leaning coalition government in 1945. This CNL-based government instituted a leftist policy program: the redistribution of wealth, introduction of a progressive income tax, economic reconstruction, and swift purging of Fascists from positions of power.29

But, as both historians and contemporary commentators have attested, this spirit of optimism was short-lived. As early as 1945, former partisan commander Ferrucio Parri was replaced as prime minister by Alcide de Gasperi, a rightist Christian Democrat, who effectively blocked most of the left-wing proposals. In Spencer Di Scala’s words:

Many Italians who fought in the Resistance believed it would be the starting point of a social revolution. Probably this hope was doomed from the start because Allied armies dominated the country, a reality the Communists rushed to recognise. Indirect Allied support allowed the conservatives to postpone indefinitely the economic provisions of the Parri government, end the purge of former Fascists and regular administrative officials tainted by Fascism, and replace CNL-nominated local authorities by traditional officials. Whether or not a revolutionary situation—or even the conditions for radical reforms—ever existed, it ended with Parri’s fall, which “marked the comeback of all the old conservative forces in Italian society.”30

As well as refusing to institute any of the Parri government’s more radical plans, the DC failed to effect the fundamental shift of power necessary to open up the state to real change. Former Fascists remained in their posts, and the structures of local and regional government were allowed to continue with little interference. And as Di Scala makes clear, Italy’s wartime allies exerted a good deal of influence at the crucial juncture. In 1947, de Gasperi made a trip to the United States, shortly after which he sacked all the leftists in his government: U.S. financial aid to Italy came on condition of a stable and rightist government, and de Gasperi was evidently taking no chances. Pier Paolo Pasolini summed up the viewpoint of the Left in claiming that “the events of 1945 were not the radical reformation of the Italian government that the Christian Democrats would claim them to have been. Rather they were superficial changes … made to ensure the continuity of power by Italian capitalists working together with the Catholic church, the politicians of the Right, and the U.S. State Department.”31 By 1948, the PCI was facing bad publicity not just from the powerful forces of the DC and its American backers but from a stream of newsreels showing Soviet troops invading East European countries and enforcing Communist regimes. The elections of that year were fought in what one critic has called an “atmosphere of anti-Communist hysteria,”32 and in April the DC won a landslide victory. It was to remain in power, almost without interruption, for the next forty-five years.

To a certain extent, the political impact of these years is explicitly present in the films, readable at the edges of the mise-en-scène and in the peripheries of the narratives. In Il Postino, an election campaign is being fought, mostly in the background of the main plot. But the stakes of this election are made visible in one sequence in which Mario tells the DC candidate Di Cosimo that he is voting PCI, only to have Di Cosimo denounce Mario and his hero Pablo Neruda, claiming that the Fascist Gabriele D’Annunzio is his poet. The right wing’s fear of the PCI is made clear in one shot of the village in which a DC election poster is visible toward the left edge of the screen, its image a hammer and sickle, with the slogan “because this isn’t your flag.” And when Di Cosimo is elected and immediately pulls out of a promised building deal, leaving Mario’s bar without its promised business, the rapid disillusionment with the DC government becomes briefly central to the narrative.

Mediterraneo does not deal with this period of disillusion, breaking off (except for its final sequence) in 1944. However, it does include the feeling of optimism about the chance to rebuild Italy among the characterizations of its rescued soldiers, verbalizing this concept quite directly through the characters of La Rosa and Lo Russo. Thus, when La Rosa arrives by plane and tells the soldiers the news of Mussolini’s fall, Italy’s division, and joining forces with the Allies, he adds: “There is much to do, we can’t remain outside of it, there are big ideals at stake.” And even more directly expressing PCI sentiments, Lo Russo tries to persuade Farina to return to Italy with him by telling him that Italy “needs rebuilding from the ground up … we’ll build a great nation, I promise you.” Similar sequences could be isolated in Cinema Paradiso, such as the scene from the other side of the political divide in which a family is forced to leave town, unable to get any work because the father is known to be a Communist.

Il Postino “Because this isn’t your flag.”

My contention is that the relation of these films to the political events of 1945 to 1948 is not primarily contained in these few direct references but is structured through a projection of politics onto romance. In each film, the moment of political possibility can be thought directly only as a moment of romantic possibility, embedded in melodramatic and nostalgic narrative of loss. In Cinema Paradiso, Totò is a young aspiring filmmaker who falls in love with Elena, the unreachable daughter of a local banker. His affair with her is brief, but he never forgets or entirely gets over her. The moment of political potential is thus rewritten in terms of his youthful belief in romance, while the scenes of his present-day cynicism construct that originary loss as determining all that comes after. Mediterraneo makes the narrative connection between the briefly textualized political excitement of La Rosa’s arrival and romance clear: in the sequence immediately after La Rosa’s patriotic speech, Farina announces his love for Vassilissa; in the following scene, the couple get married. Political potential is immediately translated into romantic potential, with the thought of Italy displaced directly onto the image of Vassilissa.

In Il Postino the imbrication of the two is even more explicit, as the film’s displacement of politics onto romance is enacted as the tension between Mario and his Communist boss over the meaning of Pablo Neruda. Whereas Mario is infatuated with the idea of Neruda as a Romantic artist, the “poet loved by women,” his boss insists that he is the poet “loved by the people.” This binary functions throughout the film to negotiate the spectator’s relationship to the narrative, in which our knowledge of Neruda’s political and historical reasons for being in Italy (and our knowledge that Mario’s boss is therefore at least partially correct) can come to function only through Mario’s textual need for poetic lessons in romance in order to woo his love, Beatrice. The text circles around this double bind of what is historically known versus what is narratively necessary. Thus, using the real historical personage of Neruda invokes extratextual knowledge: that Neruda came to Italy while in exile from Chile, and that political tensions within Italy almost had him expelled again. As Neruda’s biographer says: “He comes to Italy in search of a refuge and an amorous hideout, but even here he runs smack into the Cold War.”33 The tranquility of the island is undermined by historical tensions but is also still structured as an “amorous hideout.” What becomes central in the narrative is Neruda’s ability to coach Mario in writing poetry to seduce Beatrice, to help Mario become the “poet loved by women.”

This deflection of politics onto romance enables the films to represent the political mood of 1945, but they do so from a historically specific viewpoint: that of the time the films were made, which for the sake of brevity I will refer to as the early 1990s, although the films’ release dates span the years 1988 to 1995.34 That all three films should be made within a few years of one another, and that they should all deploy narratives of romantic loss to imagine the postwar years, is symptomatic not so much of the continuing influence of the postwar period in Italian cultural memory but of a more precise shift in the relationship between this particular history and the films’ present. This shift, which made a reimagining of the postwar years newly compelling and newly painful, included the events leading to the collapse in 1992 of the Italian First Republic.

The End of the First Republic

If the events of the early 1990s in Italy seem less well known than many of the other seismic shifts that composed the end of the Cold War in Europe, perhaps this is because there is still a debate over how much the end of the First Republic can be connected to international geopolitics and how much it was grounded in the Italian national system. For the purposes of this discussion, it is not possible to consider these questions in great detail, but it is important to understand how each element structured the postwar republic and how that system came apart when it did. The landslide victory of the DC in 1948, with its anti-Communist panic and promise of much-needed American aid, ushered in a system unique in Europe: a constitutional democracy in which, despite free elections, there was no real change of government in almost fifty years.35 As Sarah Waters has argued, Italy operated in a permanent and curiously stable state of crisis in which coalition governments rose and fell with startling frequency but remained composed of all the same politicians. The system worked principally to keep the PCI out of office, and it did so successfully by ensuring that the other two main parties, the DC and Italian Socialist Party (PSI), constantly entered into subtly changing coalitions. Cold War rhetoric and the fear of Communism, then, partly structured this oligopoly,36 but it was also composed of a vast and increasingly corrupt corporatist bureaucracy through which all elements of Italian society, from major industries to the most everyday transactions, eventually had to pass. The fact that power never changed into opposition hands enabled this system to grow unchecked, and by the 1980s the partitocrazia, or rule of the parties, was taken for granted as the definition of the Italian state.37

What precipitated the end of this system was the huge scandal that began to come to light in February 1992, when a Milanese city official was caught taking bribes.38 He named names, and those named named more names, and soon many of the country’s politicians and industrialists were implicated in what was known as Tangentopoli.39 The speed and scale of the scandal’s escalation spoke of a breakdown waiting to happen, and soon Operation Clean Hands (mani pulite) was threatening, in the words of Alexander Stille, “to overturn the party dominated system that has run the country since World War II.”40 The discoveries made by the judges were all-encompassing: from routine kickbacks in local government to the implication of top Fiat executives in bribery41 and of major politicians in Mafia deals. One-fifth of the sitting members of parliament (MPs) were put under investigation, and three former prime ministers were forced to resign, including Bettino Craxi, prime minister until the scandal broke, and Giulio Andreotti, arguably Italy’s most important postwar leader.42 Craxi fled the country to escape trial, while Andreotti stayed and was charged with advising the Mafia.43 The effect of the investigations is hard to overestimate; as one commentator put it: “Operation Clean Hands has hit Italian politics like a cyclone … after this, nothing will ever be the same.”44

A cyclone indeed. In less than two years, the entire party system imploded, as new parties such as the regionally based Northern League and media tycoon Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia appeared and won immediate support. The old parties collapsed, unable to reform themselves sufficiently to escape a total loss of public confidence. The PCI, which had split in 1991 into the moderate Party of the Democratic Left (PDS) and the hard-line Communist Rifondazione, was the only pre-1992 party still in existence by 1994.45 In April 1993, Italians voted overwhelmingly in a referendum for a change in their voting system, away from the proportional representation that had allowed for a succession of coalitions and in favor of a system closer to the “winner-take-all” or relative majority system used in the United Kingdom.46 The result of this constitutional, political, and popular upheaval was, as reported in Macleans, “what senior politicians are calling a peaceful revolution—one that promises to sweep away the web of political and financial power that has enmeshed Italy since the Second World War.”47

The collapse of the party system was sudden, but the pressures that caused it had been building up through the 1980s and had certainly reached a crisis point by the early 1990s. The conventional historical explanation for the sudden crisis is the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe: during the Cold War and thus for the entire duration of the First Republic, fear of the PCI had kept the DC in power. No matter how aware the population may have been of corruption, the status quo was successfully pitched as the lesser of two evils. When the Soviet Union broke up, there was no longer a threat greater than a corrupt regime, and so the scandals could be uncovered.48 Many historians have recently argued for a more complex explanation, not rejecting the influence of the events of 1989 but adding causes internal to Italy. Martin Bull and Martin Rhodes, for example, argue that the growing disjuncture between a successful private-sector economy and the failing state apparatus showed that the expropriation of public funds had gone as far as it could go before the whole system fell apart.49 In addition, the move toward greater European cooperation, and especially the promise of the single market in 1992, had produced a desire to become more European, in terms of both economics and culture. In this context, the Italian system seemed like a liability. In any case, it is clear that even before the final collapse of the party system, a climate was growing in which Italian public culture had to reexamine its own basic assumptions.

For Italy, such a national self-examination had to reconsider the institution of the First Republic, for only in this way could the system be viewed as historically contingent and open to change. As Stille says, “Italians are rebelling against a system they had regarded as eternal and inevitable,”50 the point being that the party system was so entrenched that political change required a change in the nature of the state. For Umberto Eco, the comparison is again to revolution: “We are living through our own 14th of July 1789.”51 Thus, the crisis forced not just a political shakeup but a reconsideration of national identity. In an article in an American magazine, Federico Fellini wrote that “all of us must reflect on what the Italian identity really means.”52 Cinema Paradiso, Mediterraneo, and Il Postino are made in this climate, and placed in context their look back to the immediate postwar years takes on a different valence. The national anxiety attending the end of the First Republic forces a return to the moment of its inception, and the leftist question What went wrong? is able to be articulated for the first time as a question of national significance.

It is for this reason that these films about the postwar years appear when they do, but this crisis of national identity also offers an explanation of why they take the form that they do. From the standpoint of the late 1980s and early 1990s, and certainly from a leftist position, 1945 signifies that moment of possibility that fails. Thus, for films to reimagine those years does entail a certain nostalgia, a yearning for the moment when a different outcome was still possible. But, contrary to the criticisms that accuse the films of using nostalgia to produce a stable and hence reactionary relation to history, the combination of 1945 and 1992 sets up a dynamic relation between past and present, in which nostalgia subtends a historical and political critique. This is why both Mediterraneo and Cinema Paradiso include sequences set in the present, in which their postwar romances are nostalgically revisited from a place of present-day loss. For example, Totò in Cinema Paradiso watches his old 8-mm films of his first love, Elena, knowing that he has never again recaptured such happiness. This loss is articulated as directly political in Mediterraneo, where the Communist Lo Russo has returned to the Greek island, decades after promising to build a new Italy. He tells Farina: “Life wasn’t so good in Italy. They didn’t let us change anything. So I told them: You win but don’t consider me an accomplice.” This moment acts as a coda to the character’s earlier optimism, but the weight of the relationship between these historical spaces cannot be borne by such direct references. Instead, such nostalgia for the moment of possibility, combined with knowledge of its inevitable failure, can be represented only in a form able to structure history in terms of loss and mourning, knowledge and desire: in other words, as melodrama.

Mourning and Melodrama

There is a substantial body of work in film theory on the ways in which melodrama has operated as a genre to psychologize ideological problems and to render them legible within a domestic or romantic frame.53 Thomas Elsaesser’s influential essay “Tales of Sound and Fury: Observations on the Family Melodrama” argues that the formal elements of mise-en-scène, alongside the claustrophobic familial narratives of classical melodrama, crystallize a particular historical and ideological structure: “This is why the melodrama, at its most accomplished, seems capable of reproducing more directly than other genres the patterns of domination and exploitation existing in a given society, especially the relation between psychology, morality and class-consciousness, by emphasising so clearly an emotional dynamic whose social correlative is a network of external forces directed oppressingly inwards, and with which the characters themselves unwittingly collude to become their agents.”54 This symptomatic reading precisely delineates a relationship among an individualized emotional narrative, a spectacular or excessive mise-en-scène, and a larger social structure, and it is within this nexus that we can begin to locate the Italian films’ staging of history.

One article that is particularly suggestive in the context of these films is Steve Neale’s “Melodrama and Tears,”55 in which Neale rereads a much-cited piece by Franco Moretti56 from a psychoanalytic and film-specific point of view. This article is useful with respect to the romance narratives of these films because it offers a way to focus on analyzing narrative structures and affect. For Moretti, the production of affect—the moment at which the reader cries—is achieved when the protagonist’s point of view is suddenly brought back into line with the reader’s, after a period in which the reader knows more than the characters. And, he argues, “what makes it produce a ‘moving’ effect is not the play of points of view in itself but rather the moment at which it occurs. Agnition is a ‘moving’ device when it comes too late.”57 Clearly, this narrative move depends on temporality, deriving its emotional effect on the reader from her realization of the irreversibility of time and the futility of any desire to make it take a different route. The Italian melodramas harness this structure of temporality and attach it to the look back on an irreversible history. Neale adds to Moretti’s outline the structure of “if only,”58 in which the moment of agnition comes with a wish that things could have been different; this wish structures the films’ look back from the present, and, in Elsaesser’s terms, translates Lo Russo’s sentiment of “if only we could have built a better country” into the protagonists’ sentiments in the domestic realm.

The final segment of Cinema Paradiso, in which a middle-aged Totò returns to his childhood home for his old friend Alfredo’s funeral, first refracts the painful look back across all the elements of his life and then condenses them by means of the film that Alfredo has left him. Here, the narrative of romantic loss operates as part of a much wider loss: that of his youth, his family whom he never sees, his best friend, his formative experiences of cinema spectatorship, and the isolated village culture that has now become modernized. These elements are invoked in turn as Totò meets his mother and sister, watches his film of Elena, revisits the now-modern square, attends Alfredo’s funeral, and returns to the Paradiso cinema for the last time before it is demolished. However, only when he goes back to Rome and views the reel of film that Alfredo left for him does the moving effect occur. The film consists of all the kissing scenes that Alfredo had been obliged to edit out of films for the Paradiso at the behest of the censoring local priest and that Alfredo had repeatedly refused to give to the young Totò.

Cinema Paradiso Totò sees Alfredo’s cinematic “letter,” provoking the film’s moving moment.

Neale discusses Moretti’s concept of point of view in filmic terms, arguing that the moving moment in film melodrama necessitates a shift of both optical and narrative points of view, although the two may not always coincide.59 This is such a moment, where the impossibility of optical points of view meeting produces tears in the spectator. In viewing this film, Totò finds out what the spectator knew all along: that Alfredo did love him and that sending him away was painful for him, done only so that Totò could succeed unhampered by his past. However, not only is Alfredo dead, but he was blind also, so Totò can see only that which Alfredo could not or, rather, that which Alfredo could have seen only in the distant past, in the postwar years of Totò’s youth. Thus a connection is made, but one structured through temporal distance and the lack of the loved object. Like Letter from an Unknown Woman (Ophüls, 1948), one of the films considered by Neale, there is a kind of letter from the dead to spark remembrance, but here the “letter” is a visual text in itself. And it is a text not of narrative but of symbolic meaning. It is not a direct message from Alfredo but consists of a performative statement: what was once unable to be seen (censored) is now visible, and Totò’s belated understanding of his own past provokes the historically located spectator to tears.

In Il Postino, the spectator does not witness the protagonist’s moment of agnition but discovers it at a remove; the realization is itself temporally displaced, too late. We discover when Neruda returns to the island some years after the events of the narrative that Mario was killed taking part in a leftist demonstration at which he was to read a poem. As Moretti says: “To express the senses of being ‘too late,’ the easiest course is obviously to prime the agnition for the moment when the character is on the point of dying.”60 And hence the moving moment occurs not because Mario has died but because of where and how he has died. Up until this point, the writing of Mario’s poetry has reflected the narrative’s displacement of politics onto romance: the poet loved by the people versus the poet loved by women. A further binary is set up between saying and doing, and in this structure the opposition between politics and romance is repeated. In its first version, Beatrice’s mother is convinced that Mario must have done something to Beatrice, not believing that he could have invented the intimate endearments of his poem. What he said, for her, is just as dangerous as what he did. In the final sequences of the film, this structure is reprised as we learn of Mario’s death. Mario never gets to read onstage, and instead we see shots of chaotic crowds and one of his poems, a piece of paper lying on the ground. What he said is once again conflated with what he did, as the “saying” of reading a poem becomes the “doing” of political action and martyrdom. But this time around, Mario’s action involves a realization of what the spectator, along with Neruda, has known all along: that politics is, after all, necessary to poetry and that speech can also constitute political action. His realization comes too late, however, and the terms are once again conflated as the political loss of the demonstration’s suppression becomes legible in the romantic loss of Mario’s death.

There is also a sequence in Il Postino that corresponds to Totò’s playing of Alfredo’s film reel and sets up another moment of communication that comes too late. Early in the film, Neruda asks Mario to describe something of the beauty of his island into a Dictaphone, for Neruda to send home to Chile. Besotted with Beatrice and unable to appreciate his surroundings, Mario can only repeat her name. Later, when Neruda has left, Mario uses the Dictaphone once more, now to attempt to record what he realizes is the true natural beauty of the island. He tries to capture the island with this inadequate technology, “recording” the color of the sky and the movement of waves. As with Alfredo’s film, Neruda does not receive this gift until Mario is dead, and hence there is no direct communication between the characters. These instances of technically mediated communication correspond to what Peter Brooks calls the “text of muteness,”61 in which melodrama is characterized by the points at which communication breaks down and only gestures are possible, not words. The mediated nature of these communications makes them something of a variation on this mute text. Mario does speak to Neruda in a way, but the speech is recorded and so, like Alfredo’s film, comes from the past. It cannot hear, and the hearer cannot reply; like film itself, the enunciation is determined through an apparatus of absence.

In this temporal displacement, the melodramatic structure reproduces the pain of historical loss; through the affective gap in the code of signification, the films condense not only the finality of the characters’ deaths but also the unbreachable space between the past moment of potential and its painful consequences in the present. Thus, temporality in these narratives works to regulate a nexus of knowledge, loss, and desire for a past state that Neale characterizes in psychoanalytic terms as the mark of failure of the fantasy of union, the falling away from the dyadic relationship of “effortless communication and mutual understanding”62 in which the subject must repeatedly mourn this originary loss. In this reading, the temporality of melodramatic affect is inevitably structured by fantasy, and, therefore, the films’ historicity also would have to be understood not simply in terms of a projection onto romantic themes but as bound up, as an affective experience, in psychoanalytic structures.

It is in this addition of a fantasy element to Moretti’s more straightforward narrative analysis that Neale’s argument offers its most productive avenue of investigation, for while these films do contain the “too late” structure of the moving text, they do so as part of a temporality that synthesizes narratives of subjective and historical loss and so involves both psychic and social mechanisms. Neale claims that crying does not occur when all conflict has ceased, as Moretti argues, but occurs as a function of an unresolved desire (the wish that things in the past could have been different), and he argues that this formulation enables a more open and more complex relation of temporality to desire. For Moretti, tears indicate a closing down of possibilities and, hence, a reactionary narrative effect. But for Neale, “an unhappy ending can function as a means of postponing rather than destroying the possibility of fulfillment of a wish. An ‘unhappy’ ending may function as a means of satisfying a wish to have the wish unfulfilled—in order that it can be preserved and re-stated rather than abandoned altogether.”63 Here, the focus shifts from the decisive point of resolution to the more ambiguous relationship between tension and resolution.

The Italian films respond to this more open-ended view of tears, whereby the “unhappy ending” performs a temporally doubled work. Within the historical narrative, the affective resolution could be said to produce tears of resignation. Alfredo and Mario are dead, and in political terms the optimism of the postwar years is definitively over. But by returning, in the present, to that history of failure, the films recontextualize the lost past in relation to an equally emotive political present that is open to change. If the past cannot be changed, its relationship to the present can be, and here the films engage with a temporality of possibility. Returning to the failed moment of the past enables a holding open of the wish and, hence, of possibility for the future. In this doubling, the films narrativize the moment of national crisis: the melodramatic production of affect does not close off movement but reenacts the historical closure of the 1940s in order to redefine, not abandon, the political stakes of the 1990s.

This notion of a doubled temporality changes our reading of nostalgia in these films, as the affective look back can no longer be thought of as simply an elision of history. If anything, the films suggest that it was the time between 1945 and 1992 that elided history and did so at the instigation of the foundational myths of the postwar nation. Thus, in Cinema Paradiso, Alfredo’s message to Totò that he must never come back, that it would be crippling and depressing, is readable as the state of Italy before it is forced to go back, as it were. The bribery scandals forced the country to reexamine its political system from the beginning, a process that required a nostalgia for lost leftist hopes and, as a corollary, the desire for change that needed to be rediscovered. If nostalgia is understood in this way, then Radstone’s critique of a Jamesonian emptiness is considerably weakened. She argues that “the endings of both Cinema Paradiso and The Long Day Closes therefore condense nostalgia for lost ideals with a pathos that suggests a wish that things might be different. Though undoubtedly ‘in question,’ phallic masculinity remains in place and History shores itself up against the incoming tide of memory.”64 But as Higson points out, the relationship between past and present in nostalgia is not always a reassuring one:

Nostalgia is always in effect a critique of the present, which is seen as lacking something desirable situated out of reach in the past. Nostalgia always implies that there is something wrong with the present, but it does not necessarily speak from the point of view of right wing conservatism. It can of course be used to flee from the troubled present into the imaginary stability and grandeur of the past. But it can also be used to comment on the inadequacies of the present from a more radical perspective.65

This is precisely the point on which Radstone’s reading of the films’ nostalgia breaks down, for while, as she says, the narratives do not end with any radical change, the impetus to critique the present vis-à-vis the specific past of the postwar years condenses exactly the historical tensions that would be instrumental in producing radical change in Italy only a few years later.

Radstone’s argument also has points of strength, and it is indeed possible to read these films’ referencing of well-known movies as mythifying a false, sentimental version of Italian-ness. Certainly, they are often referential, deriving narrative incidents and locations from films and other artifacts of Italian cultural memory. For example, Sicilian novelist Leonardo Sciascia describes his own youth at the cinema: “The showroom was an old theatre and we always went out on the balcony. From there, we spent hours spitting at the stalls; the voices of the victims burst out.”66 Cinema Paradiso contains a minor character who throughout the film does exactly this. However, just as the Sight and Sound reviewer quoted earlier felt that a British film could not represent the heritage past without the baggage of the British Empire, the nostalgic mythification of these scenes cannot help but revive the historical failure of the myth at the same time as it cites its pleasures. The generation of 1948 ultimately gave birth to Tangentopoli, and it is impossible to see images of those years without the baggage of this historical knowledge.

Nostalgia, in this context, has more in common with the psychic structures of mourning than with the regressive pleasures suggested by Radstone’s pathos or Higson’s search for “an imaginary historical plenitude.”67 Freud describes mourning as “the reaction to the loss of a loved person, or to the loss of some abstraction which has taken the place of one, such as one’s country, liberty, an ideal, and so on,”68 and it is significant that at the heart of this definition is a process of displacement. Mourning is the “normal” version of the more pathological condition of melancholia, but even within mourning, there is a complication or a perversion of the process when abstractions “take the place” of a loved person as the focus of the object loss. This is the case with the films, where the loss is of a particular idea of nation, and a historical moment stands in for a lost object. In a sense, the historical film must always invoke the process of mourning, for mourning is precisely about creating a representation of that which no longer exists. For Freud, the subject does not want to abandon his libidinal attachment to the lost object and, hence, turns away from reality to produce a fantasy in which the object can be kept alive.

But while all historical films may produce a libidinal attachment to an object that, by dint of its historicality, no longer exists, what is striking in these films is the binding together of this filmic structure both to a specific historical lost object and to a further displacement within which mourning can be narrated. Thus, in the process of mourning work, “each single one of the memories and expectations in which the libido is bound to the object is brought up and hyper-cathected, and detachment of the libido is accomplished in respect of it.”69 In these films, the memories and expectations of the postwar years are revisited through direct representation of that period but are also transfigured into romantic objects and narratives, and in this way they are hypercathected through the discourses of melodrama and affect. The plots around Farina and Vassilissa, Mario and Beatrice, and Totò and Elena70 provide a place in which mourning can occur. The films can thus be read as enacting an abstracted mourning process for the spectator, replacing an abstract object loss with the loss of a loved person at the level of narrative.

Hypercathexis is what binds mourning to melodrama: the tears that come from the object located in the past, its remembrance from the present, and the “too late” trope by which the past is made to speak more significantly in and to the present than it could in its own time. The temporality of Neale’s understanding of melodramatic affect is contiguous in these texts to the temporality of mourning: the return to the past in order to redefine the subject’s relation to the object world in the present. And in the films, both of these forms of temporal organization are imbricated with historicity—a relation to a past understood as historically determining, not merely temporally previous.

It is this nexus of relationships that readings such as Radstone’s, which take melodramatic affect as evidence for a lack of historical engagement, are unable to account for. Indicative of this problem is her placing of Cinema Paradiso as melancholic and hence as narcissistic rather than social, as “history/nostalgia” rather than truly historical. For Freud, melancholia is indeed both narcissistic and regressive, the outcome when the lost love object is removed from the other and returned to the self so that “an object-loss [is] transformed into an ego-loss.”71 Melancholia is a mourning gone awry, in which the lost object has too little resistance and the subject either does not know what she has lost or does not know what is lost in that thing. It is tempting to transpose this template onto many heritage films, to read plots that do not deal with politics or History (in either a classical or a countercinematic way) as a withdrawal from historical consciousness, and to read melodramatic structures as narcissistic, allowing the spectator only the pleasures of overidentification and empty emotion.

However, historical loss is not subsumed by ego loss in these films. Only by ignoring the specificity of Italian history would it be possible to read their postwar settings and contemporary codas as exhibiting a lack of historical friction. And while the films narrate this historical loss through individual romantic losses, this is a strategy of displacement, not replacement. The distinction becomes clear at the moments of agnition, where personal loss enables the expression of historical loss, rather than veiling or curtailing it. In Cinema Paradiso, to take Radstone’s own example, while Totò remains central to the narrative of loss, his eldest embodiment remains something of a cypher, impossible to identify fully as the child and adolescent of the majority of the film, too different an actor. And so, in the final scene, spectatorial identification is limited, and Totò functions primarily as a conduit for the spectator’s tears, tears that are provoked not by his loss but by the film reel’s signifiers of historicality, of a difference that is not contained by his character but encompasses the political and psychic gulf between that past and this present.

The Female Figure in the Landscape

What this reading of narrative in terms of nostalgia and melodrama elides is the question of gender. There is a fairly obvious feminist critique to be made here, for the films require that woman functions as a mere figure, a trope that always and only refers to something else. In locating the lost object of history within romance plots, the films map political desire onto sexual desire. The female protagonists of the romances are thus semiotically simple figures, anchoring this system of historical signification through the conventionally patriarchal codes of classical representation. All three are spectacularized and fetishized, their narrative significance defined by their excessive visibility and hence desirability in the mise-en-scène. Beatrice in Il Postino, in particular, tends to be figured in fetishistic close up, including several outstandingly extraneous shots of her cleavage. Elena in Cinema Paradiso is a cypher: first seen from the point of view of Totò’s 8-mm camera, she remains at a distance, and her disappearance from the narrative is self-consciously unexplained, a function of feminine mysteriousness. Beginning in Totò’s frame, she ultimately disappears out of the film’s frame. That both women function primarily as a shorthand of desire is clear from their names: Beatrice and Elena (Italian for Helen), both famous literary figures of beauty and loss. And while Vassilissa in Mediterraneo performs a more substantial narrative function, she embodies another kind of cultural shorthand, the stereotypical hooker with a heart of gold.

The displacement of meaning from narrative to mise-en-scène is familiar in feminist film theory, and much criticism of melodrama involves a consideration of the genre’s gendered tensions between narrative and image.72 Of course, theorists of melodrama such as Mary Ann Doane and Linda Williams73 focus on films that produce a less ideologically stable gendered image than these films do, and in which the social position of women is central. While the historical drama or heritage film is a somewhat feminized genre, these films are not women’s pictures per se, and the instrumental function of the female characters makes clear their peripheral status. It would certainly be possible to conceive of the films as male melodramas, given the passive protagonists who cannot find a place in traditional masculine domains of war or work.74 However, although such an avenue of investigation could prove productive, I bring up the question of gender not so much to offer another take on the films’ narratives but to point out a theoretical lack in the consideration of the heritage film’s image.

Cinema Paradiso Elena is a cypher, seen in Totò’s 8-mm films.

As I argued earlier, there is an anxiety around the image in criticism of these films, a fear of the spectacular historical image that implicitly looks to a formal realism to secure historical authenticity. Mise-en-scène does have a role within this discourse of grounding the narrative image accurately, but anything excessive to narrative necessity casts doubt on the seriousness of the enterprise. (Within this discourse, for example, a film like Saving Private Ryan [Spielberg, 1998] could deploy a visually excessive and affective mise-en-scène of broken and mutilated bodies, for the images were justified rhetorically as more realistic than those in any previous war film.) Thus, for Radstone or Jameson, the nostalgic image is too beautiful to be true, and for Higson the so-called heritage shots of aesthetically pleasurable views or buildings “fall out” of the narrative.75 Each claim about historicity is based on a splitting of the functions of narrative and image, a binary structure in which visual pleasure works only to undermine—or, better, to halt—the possibly radical signification of historical narrative.

What is striking is the extent to which this discourse is predicated on the structures of feminist film theory and yet deradicalizes its conception of the image. For clearly Higson’s spectacular heritage shots that “fall out” of the narrative owe a debt to Laura Mulvey,76 but in a simplified rhetoric in which these moments of spectacular freezing can indicate only a blockage of meaning. To be sure, the context of psychoanalytic theory is lost, but in shifting the terrain from patriarchal images to historical representation, the ideological complexity of spectacle is also left behind. For Mulvey, neither spectacle nor narrative is negative simply by refusing meaning; rather, both operate as part of an intensely productive ideological system. And in much psychoanalytic feminist theory following Mulvey, the image is a privileged site of contestation, the place where hegemonic meanings can start to break down. Thus, while questions of gender may be peripheral to the narratives of these films, I would argue that feminist film theory is crucial to theorizing the relation they propose between historical narrative and spectacular mise-en-scène. Against Higson’s logic, it is crucial to theorize as productive the pleasures of spectacular historical images.

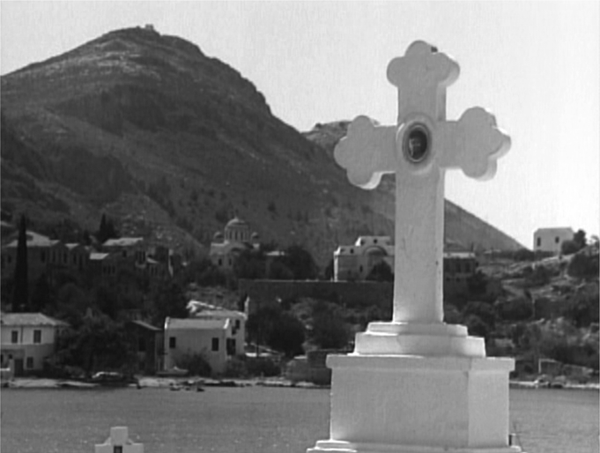

The chief locus of spectacle in these three films is landscape: an Italian rural landscape in Cinema Paradiso and Il Postino and a Greek island in Mediterraneo. Each film was shot on location, and the narratives take place within spaces coded as spectacular, from the sequences in which Mario and Neruda talk on the beach in Il Postino to Totò’s walks with the priest along a country road that overlooks a dramatic shoreline in Cinema Paradiso. In addition to these narratively motivated locations, there are many instances of shots and sequences that are not motivated, that function directly as visually pleasurable spectacles: landscape images that indeed “fall out” of the narrative. Mediterraneo, for example, begins by setting up suspense around its thus far largely unseen narrative space. The soldiers disembark from their boat to find an apparently deserted island and some graffiti that threatens “Greece is the tomb of Italians.” But soon this threat is dissipated as the inhabitants reveal themselves to be friendly, and montage sequences of the various spaces of the island, now unconnected from any narrative tension, reveal direct spectatorial engagement with the landscape to be one of the chief pleasures of the film. Such moments can readily be compared with the “heritage shots” in British heritage films, although the content of the images is naturally quite different. Rather than showing country houses or gardens, the Italian films focus on uncultivated spaces: mountains, bays, and seascapes; and pre-modern, peasant villages or small towns. These rural spaces work to connote historicality, for in addition to avoiding more up-to-date locations like cities, the unchanging nature of landscapes works alongside representations of traditional practices such as fishing to produce a sense of distance from the modern world.

Il Postino Pablo Neruda views the Mediterranean seascape.

Mediterraneo The soldiers are integrated into the local landscape.

This connection of landscape to pastness, or to a rural lifestyle that appears historically rather than merely geographically distant, certainly has a long history in forms such as naturalism in literature and pastoral landscape painting of the kind that Warnke discusses. But as cinematic images, these mountainscapes and seascapes need to be considered in relation to landscape photography, for it was in photography that landscape took on the discursive baggage that helps form the critical response to these films as spectacle. Rosalind Krauss argues that not only does landscape photography have to be understood in a different context from painting, but there are (at least) two very different discursive contexts for landscape images within photography and photographic texts tend to be misread when these get conflated.77

Krauss discusses the reception of a series of nineteenth-century photographs that were generally read within the dominant modernist art photography discourse as graphic images in which the surface of the photograph, its framing, and its composition are primary and the aesthetics of representation takes precedence over the realistic qualities of the image. She contrasts this interpretation with the photographs’ original context, a scientific mapping of geographic space. She connects this form to the introduction of “views” within Victorian mass culture and thus to a popular discourse of landscape as a form of scientific-touristic knowledge. Now, clearly, film is not the same thing as photography, and it is as important not to conflate the two as it is to avoid conflating nineteenth-century views with modernist art photographs. Still, Krauss’s discussion sets up the terms for the ways in which contemporary film landscapes are still read and, by extension, suggests how similar interpretative strategies in the context of cinema might produce new readings. For Krauss, the problem is that photographs that should be read within the epistemological context of the view are instead misunderstood as modernist art images. But in contemporary cinema, an ambivalent version of both these discourses is at work, producing an epistemology specific to contemporary film landscapes.

First, there remains a broadly modernist aestheticizing discourse that reads landscape graphically as surface. This mode is often valorized in the context of art cinema where a nonrealist mise-en-scène is part of a claim to radicality. And in postclassical film, art-cinematic visual strategies are sometimes central to the location of certain popular films as quality products, as in the epic vistas and self-consciously aesthetic cinematography of The English Patient. But this example demonstrates the ease with which the valorizing impulse can slip into a fear of pictorialism, producing a criticism of “all style, no depth.” This fear of mise-en-scène, in which landscape becomes readable as a screen blocking a perceived narrative depth, is peculiar to cinema, and especially to a postclassical cinema in which visual excess has become closely linked to claims of a process of “dumbing down”—of deteriorating content.78 Not identical to Higson’s critique of the heritage image, this ambivalence nonetheless imbues his reading of the pictorial.

Krauss’s second discursive context—the nonauthored, scientific, or popular view—is also part of contemporary cinema, and although as a mode of perception it has been less aesthetically dominant than modernism, recent work on the visual history of tourism and the touristic image has traced recurrent patterns from such nineteenth-century views to picture postcards and cinematic practices.79 Once again, what is substantially a positive rereading in Krauss applies mostly as critique in the context of film, where claims of a touristic view imply either a scholarly argument around colonialism and the gaze or a critical accusation like those leveled at Cinema Paradiso and Mediterraneo that the film is clichéd and stereotypical. Although the former claim is more relevant to an example like The English Patient, the problem is not with this argument in itself but with its indiscriminate application to all landscape images. For while Krauss is able to structure these two contexts as alternatives for interpreting photographs, in the field of contemporary cinema the two work together to form a lose–lose structure. On the one hand, the films are too artistic, posing landscape as graphic composition and favoring aesthetics as form over meaning. On the other hand, they are too popular, replicating a touristic gaze typical of bourgeois pop culture in which the landscape image can signify only distraction and a lack of geographic or historical friction. In either case, the image is once again the site of a lack, a falling away from meaning.

The difficulty, then, is to think landscape outside this epistemological bind: to read it not as a sliding surface, an aporia of meaning, but as a specific form of spectacular image that produces meanings and spectatorial relations as complex and ambiguous as those produced in other types of spectacle. To begin to rethink landscape in this way, it is necessary both to bring back to the surface the feminist work that offers a film-specific understanding of the structures of the image and to analyze what happens differently when the image is not tied to a gendered body. If the female characters in the films can, in classical terms, be seen as images standing for desire, what can landscape as spectacle stand for?

One way to address this issue is through the discursive context of another body of Italian films in which landscape became a privileged site of meaning: neorealism. Made mainly between 1945 and 1948, neorealist films are concurrent with the moment of political optimism that the 1990s films mourn, and neorealism represents many of the same geographic spaces. Furthermore, in neorealism, landscape is often claimed to be central to the films’ project of reclaiming Italy for an anti-Fascist identity. Thus, Paisà represents Italian resistance and liberation through a series of narratives, each set in a different geographic location, while La terra trema focuses on exploited workers in a rural Sicilian fishing village. On the films of Giuseppe De Santis (and particularly Tragic Hunt [1947]), Mira Liehm says that they work to create a “dramatically presented landscape, which was not permitted on the screen during the fascist regime.”80 There is an inkling here of the political historicity of landscape that I will address in more detail, but I want to concentrate for now on De Santis’s own valuation of his landscape imagery, which he outlines in an article entitled “Per un paesaggio italiano.”81