Cease C’s and attain A’s

Picture this:

You have a test tomorrow morning on George Washington and the American Revolution. To study, you read over your notes and the assigned chapters, and it pretty much makes sense. You get a good night’s sleep, chomp down cereal for breakfast, and march confidently into the test. You get a C+.

What went wrong?

Not enough sleep? Unlikely, since you got nine hours. (Useful statistic: Nine hours of sleep is recommended for mental alertness.)

A problem with your choice of breakfast? Very unlikely—while cereal is not the healthiest breakfast you can eat, there’s no evidence that it makes any difference in social studies test performance.

Much more likely is that you weren’t studying actively enough. You weren’t making good use of Your Mind’s Activator.

Regrettably, this is a problem for many students. If you just read over your George Washington notes and remember what they say, you’re going to get pounded if the test asks something really hard. For the best results, and to shift from C+ to A, you have to actively do something with the information you’re studying. That’s true for George Washington, geometry, geology—almost any subject at school. This chapter shows you how to shift from passive to active studying.

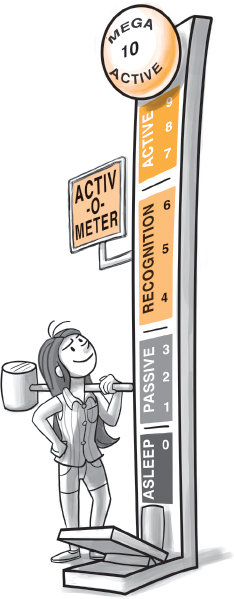

To help you understand the difference between passive and active studying, check out the Activ-O-Meter.

0: Asleep. This is the lowest level of mental activity, and obviously, the worst for studying. Fact: If you study about George Washington while sleeping, you will learn nothing about George Washington. (Though at least you’ll feel rested while failing the test.)

1–3: Passive. You’re not asleep, but you might as well be. You see and hear information but don’t really think about it.

4–6: Recognition. A little better. At this level, you read over the material and understand it. The problem is that “understanding” it is not the same as “remembering” or “explaining” it. Sure, you might understand something when you read it Tuesday night, but that doesn’t mean you’ll remember it for a test Wednesday morning. It also doesn’t mean you’ll be able to explain it in an essay or apply it to a new problem.

7–8: Active. Much better. At this level, you’re making connections in your mind. And these connections are what enable you to remember and answer best. For example, let’s say you learn the definition for the Stamp Act, and even write it down:

Stamp Act: American colonists had to pay extra taxes for stamped paper.

That’s nice, and if the test asks you to define the Stamp Act, you’re probably okay. But what if the test asks you to “explain the relationship between the Stamp Act, the French and Indian War, and the American Revolution”? For tests with questions like this (which are common), you need to study more actively. You need to make connections. With the Stamp Act, for example, the important connections are:

1. England had just spent lots of money on the French and Indian War and needed to raise taxes to pay for it.

2. Colonists found this unfair. They started to think about a government of their own.

When you make connections like these, you understand the Stamp Act (or whatever you’re studying) in a much deeper way. You’re also much better prepared when the teacher asks you difficult questions about it.

9–10: Mega-Active. Best. Here, you do more than make connections in your mind. You extend and apply them to something completely different. This gets into the really intense questions teachers love to dish out, and also the hardest questions on tests. These are questions like, “If you were King of England in 1770, what would you do to stop the revolution in America, and why?” or “How might the Revolution have turned out differently if George Washington hadn’t been in command?” When you can answer questions like these, you understand the material a whole lot better.

When you really need to understand something, crank up your mental activity. Here is a four-step method for doing that. Use it when studying for tests.

STEP 1.

PREDICT WHAT YOU’LL NEED TO KNOW

The first step in studying for any test is to know what to study. Sometimes this is very clear: The teacher specifically spells out the topics and questions beforehand. Sometimes, on the other hand, this seems impossible: The teacher doesn’t explain or says things that confuse you. Most often, it’s somewhere in between: The teacher gives hints and messages, and it’s the students’ job to figure them out.

Here are some clues:

• What’s been emphasized so far? If the teacher spent 45 minutes on Battle X and two minutes on Battle Y, expect to see much more of Battle X on the test.

• What were prior tests like? “Given that she asked this about Christopher Columbus, and that about the Mayflower, what’s she likely to ask about George Washington?”

• Prepare for the worst. For example, maybe you’re not sure whether the test will ask “Who were the first three presidents of the United States?” or “What was Washington’s influence on Thomas Jefferson’s presidency?” Don’t just cross your fingers and hope for the easy one. Instead, make sure that you can answer both.

Tip. If you’re still unsure what will be on the test, ask the teacher. Many teachers love to help.

Keeping It REAL

“When I have to get ready for tests that have essays, I make a list of possible essay questions. I think of the main things that we covered in class. I predicted one that showed up on the history test we just had!”

—Nicole

STEP 2.

RECALL THE CONTENT

It’s usually not enough to be able to recognize the material when you see it. Most tests require that you actively remember it. So when studying, test yourself to make sure you can actually recall what you’ve studied.

Here’s a good method:

• Every time you finish reading a chapter or notes, cover everything below the title for each section. Then retell the content in your own words. This is called paraphrasing. If you can do that, make a plus sign (+) in the margin—if not, mark a minus (-).

• Repeat that process until you’ve earned three plus signs for a section. Now you can be pretty sure you know that material and don’t need to review it again until just before the test.

• Move on to other sections until you’ve earned three plus signs for each section.

STEP 3.

MAKE RELATIONSHIPS

Here’s where you crank up into very active thinking. First, think about the relationships involved: How is one idea similar to another? How is it different? How did one event lead to the next?

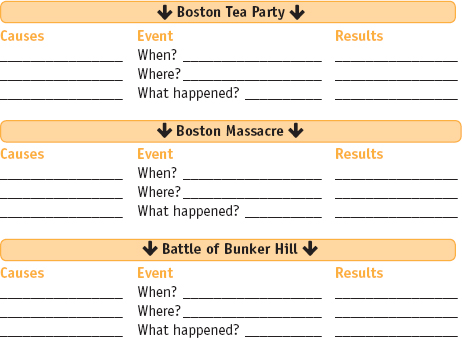

Second, take ideas, which can get pretty abstract, and convert them into visual images—something to actually show the relationships. Three ways to do that are using visual organizers, timelines, and Venn diagrams.

Visual Organizers

These are useful when you have a lot of information. With so much to think about, it’s hard to keep it all straight. Visual organizers help arrange the information into one compact space that’s easy to see. Check out this example:

Keeping It REAL

“What I usually do is I make this big poster with all the things that I need to know, separate it into sections, and look through it all the time. I put it up on my wall and look at it every day.”

—Ruth

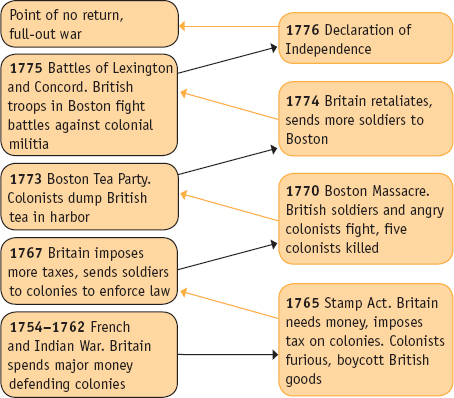

Timelines

These are especially useful for tracking events over time. Timelines can help you see how one thing leads to another and another. Indeed, most major events, like the American Revolution, don’t just happen overnight. They build up for a very long time. To keep track of all this and see it clearly, use a timeline. Here’s an example:

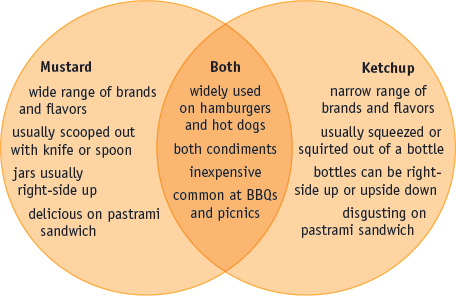

Venn Diagrams

These are great for the age-old compare and contrast questions, such as, “How are George Washington and Ben Franklin similar and different?” Even if you don’t think questions like that will be on the test, doing Venn diagrams can help you understand the material in a deeper way. To make one, you draw circles to show where the two things overlap (similar) and where they don’t (different).

For example, here’s a Venn diagram that answers the question “Compare and contrast mustard and ketchup.”

Venn diagrams can be useful in just about any subject. In English language arts, you can learn more about your reading material by making a Venn diagram for two major characters. Or you could use a Venn diagram to compare two different pieces of literature. In biology, a Venn diagram could be very useful for comparing species of living things or habitats.

STEP 4.

APPLY AND EXTEND

Apply and extend means you take the material and apply it to something new or extend it in some novel direction. Many teachers put apply-and-extend questions on tests, and these can be really tough.

There are four types of apply-and-extend questions that pop up again and again. If you can handle these four kinds of questions, you’ve probably nailed the material. Invent apply-and-extend questions for yourself after you read over your notes or chapters. Then spend time answering them. For extra mind activation, write down your answers.

Here are four typical kinds of apply-and-extend questions:

You Go There

In this question type, you’re magically transplanted into a different time and place and asked what you’d do there. This usually takes one of two forms: Imagine that you are somebody famous (“If you were the prime minister of Canada, would you have supported joining World War II? Why or why not?”). Or imagine that you are somebody normal (“If you were a Toronto business owner in 1939, would you support or oppose joining the war, and why?”).

This kind of apply-and-extend question works in many subjects. In literature: “Imagine you are the main character in the story. What would you do when you find the lost treasure?” In science: “You’ve invented a machine that takes you to the center of the earth. What geological layers do you pass along the way, and what dangers do you face at each layer?”

They Come Here

This is the flip side of the “You Go There” question type. In this format, someone famous is transported to the here-and-now and you’re asked to explain his or her position on some modern-day issue. For example, “If Darwin were alive today, what would he think about global climate change?” Or “If a T. rex reappeared on Earth, on what continent would it best flourish?”

What-If

In these apply-and-extend questions, you consider what would have happened if important events had turned out differently. For example, “If England had defeated the American Revolution, how would your life be different?” What-ifs can also be used for literature by asking questions like “How would the story be different if the main character had not answered the doorbell?” Or in science: “What if a meteor landed in the Pacific Ocean—how might our lives be affected?”

Evaluate

In this apply-and-extend format, you’re given a statement and asked to agree or disagree and explain why. For instance: “Evaluate the statement ‘Power companies should create much more electricity from wind.’” In this case, your job is to evaluate both sides of the argument—reasons why power companies should use more wind and reasons why they shouldn’t. Then choose one side or the other and support it.

App Demonstration: Robert

Math is my hardest subject at school. I used to dread math tests. But last semester I started using my mind’s Activator to prepare for tests, and I have been doing a lot better. Here’s how I’m preparing for my next test.

STEP 1.

PREDICT WHAT I’LL NEED TO KNOW

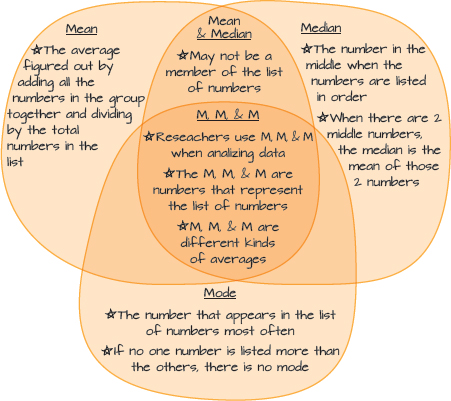

For the past two weeks, we’ve been going through Chapter 6 about analyzing data. My teacher, Ms. Z, has also spent forever talking about mean, median, and mode. We measure mean, median, and mode in all kinds of ways: temperatures for particular time periods, population growth over time, popularity of different YouTube videos. As a result, I’m almost positive that she’ll put something like that on our test.

Also, when I think back to the last couple of tests, I noticed that she starts out with easy problems like in the homework. Then the last few are always “stretch questions.” I bet she does the same for this test.

STEP 2.

RECALL THE CONTENT

To make sure I can recall mean, median, and mode from memory, I cover up the definitions I wrote in my notebook. Then I retell them in my own words. I also make up examples of each. Once I can do that correctly three different times, I know that I’ve got it.

* Mean is the mathematical average. The mean of 8, 9, and 19 is 12 (8 + 9 + 19 = 36, and 36 divided by 3 equals 12).

* Median is the middle number. The median of 8, 9, and 12 is 9.

* Mode is the most common or “popular” number (what’s in fashion or in mode). The mode of 8, 9, 12, 12, 17 and 19 is 12.

STEP 3.

MAKE RELATIONSHIPS

Unfortunately, just being able to state the definitions won’t get me all that far on the test. Knowing Ms. Z, I’ll probably also have to compare and contrast all three: how are mean, median, and mode similar and different from each other? Time for a Venn diagram:

STEP 4.

APPLY AND EXTEND

To get ready for Ms. Z’s stretch questions, I apply and extend.

First, I come up with different situations or sets of data. Second, I ask which one works best for each—mean, median, or mode—and why. (This is totally the kind of thing Ms. Z loves to put on tests.) Third, I answer the questions.

Which Work Best? Mean, Median, or Mode?

1. Given the following test scores, how did the class do on last year’s math final? 83, 87, 88, 95, 92, 89, 99, 86, 52, 55, 60

2. How many students come to school by foot, bus, train, car, or bicycle?

3. What’s the average of the following yearly salaries among professional hockey players? $2 million, $1.5 million, $2.5 million, $2 million, $2.25 million, $1.75 million

Answers

1. Median is the best measurement here. Because there are outliers (52, 55, 60), those scores pull the mean way down, making the class average look too low if using a mean. (The median is 89.)

2. Mode is best here. Mode means “what’s the most common value,” and this question is asking about the most common form of transportation.

3. Trick question. Mean, median, and mode all come out to $2 million here.

Here is a reading about a topic from history. This kind of reading can be boring and hard to focus on. Imagine you now are going to face a test on this topic. Use Your Mind’s Activator to learn it well and prepare for the test.

Asian Nobility of the 18th Century

In Asia during the 18th century, nobles were the highest class of society. Nobles were only one step below the ruler. Although they enjoyed wealth, power, and prestige, they were tightly controlled by their rulers. In Japan, that ruler was the shogun. In China, it was the emperor.

Japanese nobility were called daimyo. Daimyo were military lords who had power over a large territory given to them by the shogun. The shogun controlled the daimyo by forcing them to spend every other year in the capital city of Edo. During years when daimyo went back home to their estates, their family members were required to stay in Edo. The shogun figured that daimyo would be less likely to attack him if their family members were living nearby. The shogun also kept the daimyos’ wealth in check by forcing them to contribute money to help build roads, bridges, and urban buildings.

In China, the political power and influence of nobles was diminished by a merit testing system. Many top-ranking government officials were required to pass a difficult academic test rather than simply inheriting their jobs. There was also a complicated ranking system that prevented families from keeping too much power. Very often, a noble’s oldest son could only inherit a rank one step lower than his father’s. Earlier in history, Chinese nobility were forced to live in Beijing. They could only leave if given permission by the emperor.

Follow the four steps of Your Mind’s Activator.

1. PREDICT WHAT YOU’LL NEED TO KNOW

The first step in preparing for this imaginary test is to figure out what will probably be on it. Start by predicting questions for the test, and be sure you can answer them. When doing this, consider the following:

• What are the most important points in this reading? (And therefore what is the teacher most likely to ask?)

• What issues in this reading has the teacher emphasized the most in class?

• What kind of questions has the teacher asked on prior tests?

Better yet, put yourself in the teacher’s shoes and make up the test yourself. What are the best questions to ask about this reading? When you imagine you’re teaching, that’s very active. You’re selecting what’s important and explaining it in a way that makes sense.

2. RECALL THE CONTENT

Test yourself to be sure you can actually recall what you’ve read. Do the +/- review. Go back to the reading and check off whether you can paraphrase each section from memory. When you earn three + marks on Japan, move on to China.

3. MAKE RELATIONSHIPS

Think about how Japanese and Chinese nobility were similar and how they were different. Make a Venn diagram: two overlapping circles that visually show the similarities and differences.

4. APPLY AND EXTEND

To get your mind Mega-Active, answer the following questions:

1. If you were a noble in the 18th century, would you rather live in Japan or China? Why?

2. If the Japanese daimyo took over the U.S. Congress tomorrow, would it work better, worse, or no differently? Why?

|

Use Your Mind’s Activator |

Don’t Use It |

|

Earn better grades |

Earn poorer grades |

|

Connect and get engaged with schoolwork |

Sit back and stay bored |

|

Go deep, answer hard questions |

Stay on the surface, answer easy questions |

|

Make connections that register information in your mind |

Forget stuff right after you learn it |