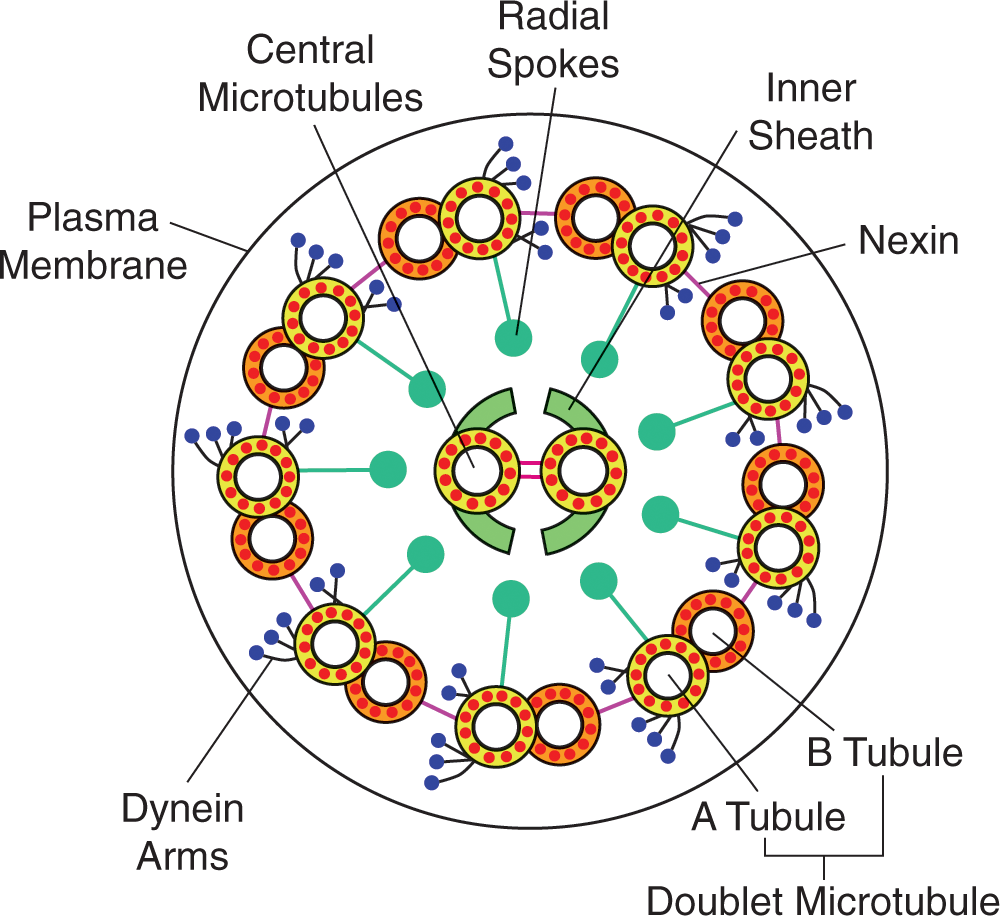

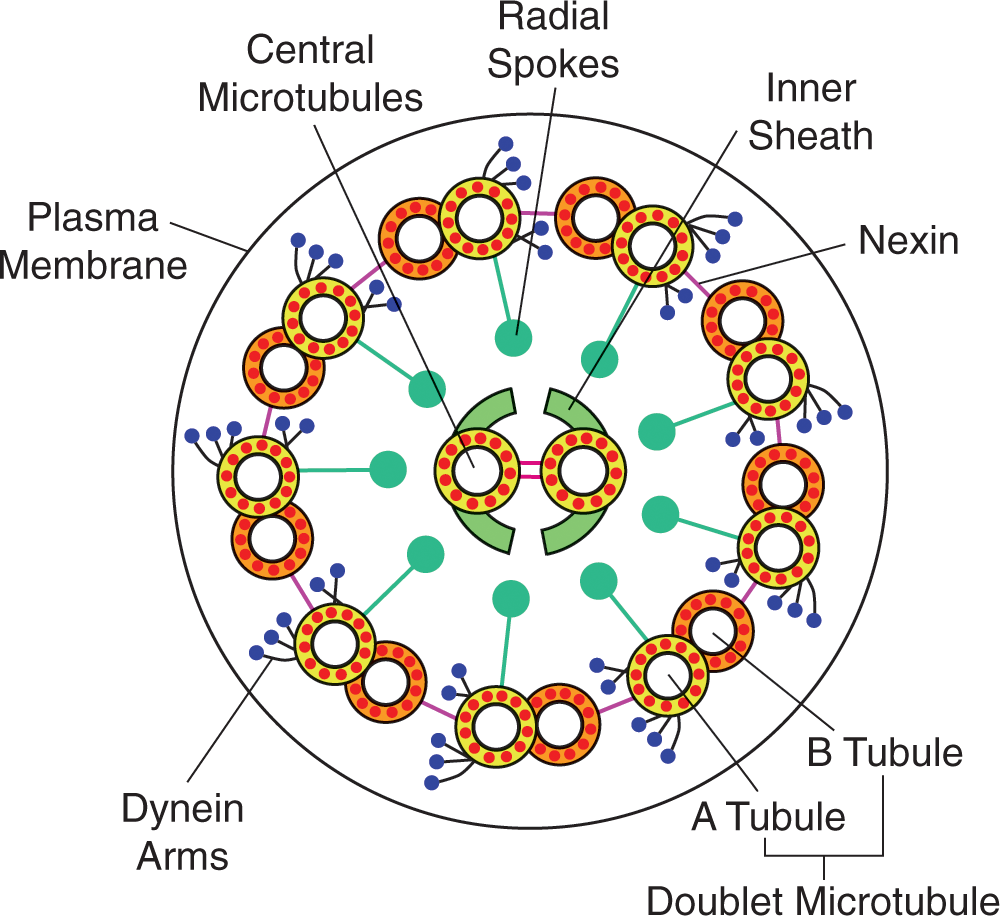

Microtubules are organized into a ring of 9 doublets with 2 central microtubules.

The human body contains approximately 37 trillion cells. These cells create tissues from which organs form. Each cell serves a purpose, communicating and carrying out the reactions that make life possible. Interestingly, bacterial cells outnumber the eukaryotic cells in our bodies about 10 to 1. But the sheer number of cells from which the human body is created is not nearly as impressive as the numerous functions these cells can perform, from conduction of impulses through the nervous system, which allow for memory and learning, to the simultaneous contraction of cardiac myocytes, which pump blood through the entire human body.

The first major distinction that can be made between living organisms is whether they are composed of prokaryotic or eukaryotic cells. Eukaryotic organisms can be either unicellular or multicellular. Eukaryotic cells contain a true nucleus enclosed in a membrane; prokaryotic cells do not contain a nucleus. The major organelles are identified in the eukaryotic cell.

Each cell has a cell membrane enclosing a semifluid cytosol in which the organelles are suspended. In eukaryotic cells, most organelles are membrane bound, which allows for the compartmentalization of functions. Membranes of eukaryotic cells consist of a phospholipid bilayer. This membrane is unique because its surfaces are hydrophilic, electrostatically interacting with aqueous environments inside and outside the cell; its inner portion, on the other hand, is hydrophobic, which helps provide a highly selective barrier between the interior of the cell and the external environment. The cytosol diffuses molecules throughout the cell. Within the nucleus, genetic material is encoded in deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), which is organized into chromosomes. Eukaryotic cells reproduce by mitosis, which results in the formation of 2 identical daughter cells.

As the control center of the cell, the nucleus contains all the genetic material necessary for replicating the cell. The nucleus is surrounded by a nuclear membrane or envelope, a double membrane that maintains a nuclear environment separate and distinct from the cytoplasm. Nuclear pores in the nuclear membrane allow for the selective, 2-way exchange of material between the cytoplasm and the nucleus.

The genetic material (DNA) contains coding regions called genes. Linear DNA is wound around organizing proteins called histones, which are then further wound into linear strands called chromosomes. The location of DNA in the nucleus allows for the compartmentalization of DNA transcription separate from ribonucleic acid (RNA) translation. Finally, in a subsection of the nucleus known as the nucleolus, ribosomal RNA (rRNA) is synthesized. The nucleolus actually takes up approximately 25% of the volume of the entire nucleus and often can be identified as a darker spot in the nucleus.

Mitochondria often are called the power plants of the cell, in reference to their important metabolic functions. The mitochondrion consists of 2 layers: the outer and inner membranes. The outer membrane serves as a barrier between the cytosol and the inner environment of the mitochondrion. The inner membrane, which is thrown into numerous infoldings called cristae, contains the molecules and enzymes necessary for the electron transport chain. The cristae are highly convoluted structures that increase the surface area available for electron transport chain enzymes. The space between the inner and outer membranes is called the intermembrane space; the space inside the inner membrane is called the mitochondrial matrix. The pumping of protons from the mitochondrial matrix to the intermembrane space establishes the proton-motive force; ultimately, these protons flow through ATP synthase to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP) during oxidative phosphorylation.

Mitochondria are different from other parts of the cell because they are semiautonomous. They contain some of their own genes and replicate independently of the nucleus via binary fission. As such, they are paradigmatic examples of cytoplasmic or extranuclear inheritance—the transmission of genetic material is independent of the nucleus. Mitochondria are thought to have evolved from an anaerobic prokaryote that engulfed an aerobic prokaryote, thus establishing a symbiotic relationship.

In addition to keeping the cell alive by providing energy, the mitochondria also are capable of killing the cell by releasing enzymes from the electron transport chain. This release kick-starts a process known as apoptosis, or programmed cell death.

Lysosomes are membrane-bound structures containing hydrolytic enzymes that are capable of breaking down many different substrates, including substances ingested by endocytosis and cellular waste products. The lysosomal membrane sequesters these enzymes to prevent damage to the cell. However, release of these enzymes can occur in a process known as autolysis. Like mitochondria, when lysosomes release their hydrolytic enzymes, apoptosis occurs. In this case, the released enzymes directly lead to the degradation of cellular components.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) comprises a series of interconnected membranes that are actually contiguous with the nuclear envelope. The double membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum is folded into numerous invaginations, creating complex structures with a central lumen. The 2 varieties of ER are smooth and rough. The rough ER (RER) is studded with ribosomes, which permit the translation of proteins destined for secretion directly into its lumen. Smooth ER (SER) lacks ribosomes and is used primarily for lipid synthesis (such as phospholipids in the cell membrane) and the detoxification of certain drugs and poisons. The SER also transports proteins from the RER to the Golgi apparatus.

The Golgi apparatus consists of stacked membrane-bound sacs. Materials from the ER are transferred to the Golgi apparatus in vesicles. Once in the Golgi apparatus, these cellular products may be modified by the addition of various groups, including carbohydrates, phosphates, and sulfates. The Golgi apparatus also may modify cellular products by introducing signal sequences, which direct the delivery of the product to a specific cellular location. After modification and sorting in the Golgi apparatus, cellular products are repackaged in vesicles, which are subsequently transferred to the correct cellular location. If the product is destined for secretion, then the secretory vesicle merges with the cell membrane, and its contents are released via exocytosis.

One of the primary functions of peroxisomes is the breakdown of very long chain fatty acids via beta-oxidation. Peroxisomes contain hydrogen peroxide, participate in the synthesis of phospholipids, and contain some of the enzymes involved in the pentose phosphate pathway.

The cytoskeleton provides structure to the cell and helps maintain the cell’s shape. In addition, the cytoskeleton provides a conduit for transporting materials around the cell. The 3 components of the cytoskeleton are microfilaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments.

Microfilaments are composed of solid polymerized rods of actin. The actin filaments are organized into bundles and networks and resist both compression and fracture, providing protection for the cell. Actin filaments also can use ATP to generate force for movement by interacting with myosin, such as in muscle contraction.

Microfilaments also play a role in cytokinesis, or the division of materials between daughter cells. During mitosis, the cleavage furrow is formed from microfilaments, which organize as a ring at the site of division between the 2 new daughter cells. As the actin filaments within this ring contract, the ring becomes smaller, eventually pinching off the connection between the 2 daughter cells.

Unlike microfilaments, microtubules are hollow polymers of tubulin proteins. Microtubules radiate throughout a cell, providing the primary pathways along which motor proteins such as kinesin and dynein carry vesicles.

Cilia and flagella are motile structures composed of microtubules. Cilia are projections from a cell that are primarily involved in the movement of materials along the surface of the cell; for example, cilia line the respiratory tract and are involved in the movement of mucus. Flagella are structures involved in the movement of the cell itself, such as the movement of sperm cells through the reproductive tract. Cilia and flagella share the same structure; they are composed of 9 pairs of microtubules forming an outer ring, with 2 microtubules in the center. This 9 + 2 structure is seen only in eukaryotic organelles of motility. Bacterial flagella have a different structure with a different chemical composition, which will be discussed later in this chapter.

Centrioles are found in a region of the cell called the centrosome. They are the organizing centers for microtubules and are structured as 9 triplets of microtubules with a hollow center. During mitosis, the centrioles migrate to opposite poles of the dividing cell and organize the mitotic spindle. The microtubules emanating from the centrioles attach to the chromosomes via complexes called kinetochores and can exert force on the sister chromatids, pulling them apart.

The diverse group of filamentous (intermediate) proteins includes keratin, desmin, vimentin, and lamins. Many intermediate filaments are involved in cell-cell adhesion or the maintenance of the overall integrity of the cytoskeleton. Intermediate filaments can withstand a tremendous amount of tension, making the cell structure more rigid. In addition, intermediate filaments help anchor other organelles, including the nucleus. The identity of the intermediate filament proteins within a cell is specific to the cell and tissue type.