The heart is special in that it is the only organ to completely generate its own electrical impulse, conduct it completely through the entire muscle, and operate completely free on innervation. Four properties contribute to this unique ability of the heart.

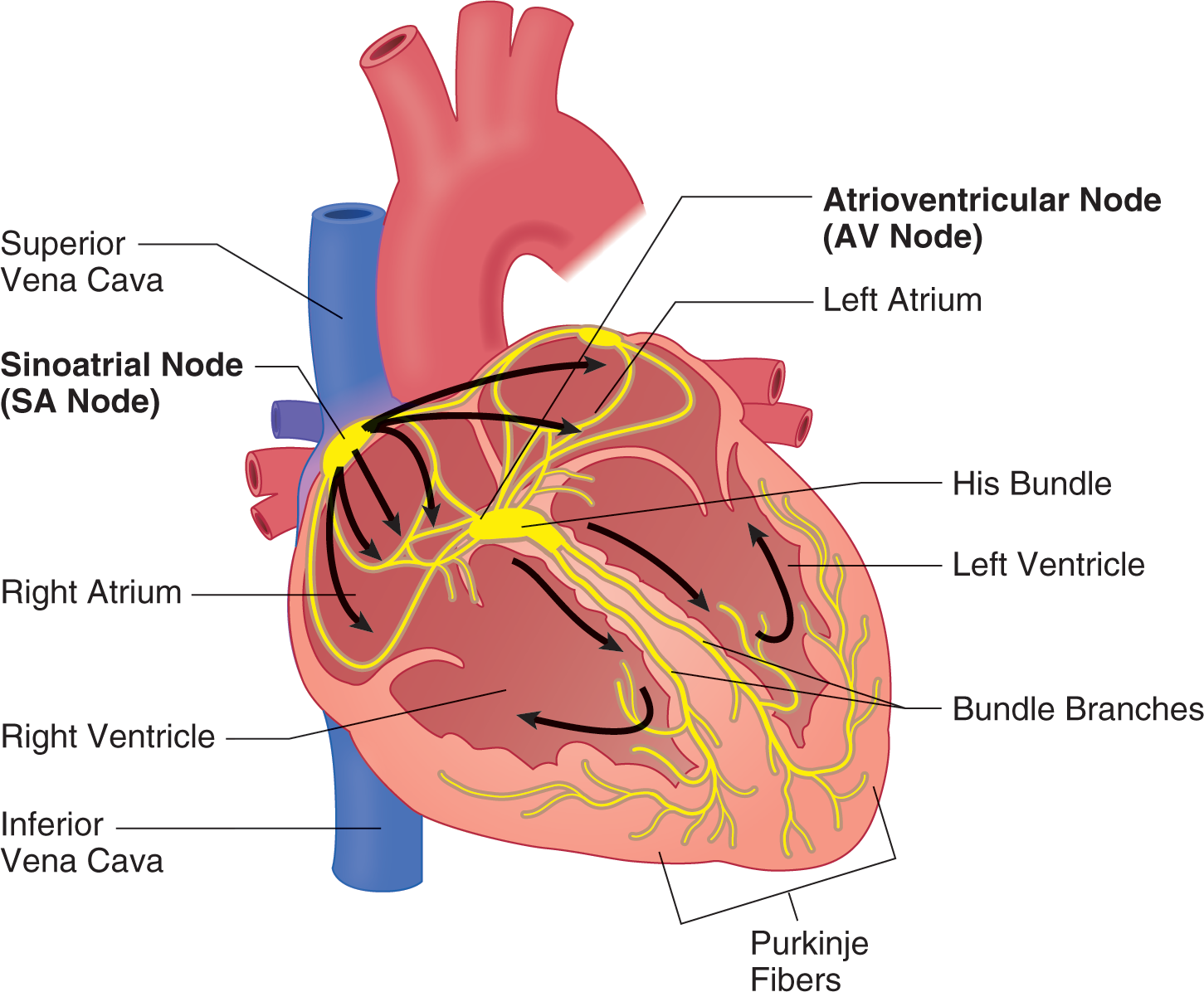

The SA node is the pacemaker of the heart and is an area in the right atrium that normally sets the rate of the heart. However, any area that sets the heart rate is called the pacemaker site. For now, the focus will be on the normal electrical pathways of the heart and what passage of the electrical impulse through these pathways means for both the mechanical action of the heart and the appearance on the electrocardiogram (ECG). To fully understand all of this, a discussion on cellular polarity, depolarization, and repolarization is needed.

When muscle cells are relaxed, an electrical potential is established across the muscle cell membrane. Muscles actively pump out positively charged sodium ions into the intercellular space, which leaves the inside of the cell negatively charged relative to the outside. This establishes an electric gradient across the cell membrane of approximately –90 millivolts (mV), indicating that the inside of the cell is negatively charged. Once this is established, the cell is said to be polarized.

When the cell receives the signal from the nervous system, or in this case the electrical conduction system of the heart, this polarized muscle cell depolarizes. When this happens, the permeability of the muscle cell membrane changes, and Na+ ions rush into the cell along with some calcium ions, effectively reducing the electrical gradient to 0 mV. In muscle cells, a depolarized cell is contracted. Therefore, when it is said that, for example, “the ventricles are depolarized” or “a part of the ECG refers to the depolarization of the ventricles,” this means that the ventricles are contracted or contracting at that time.

Once a cell has depolarized, it cannot do anything more until it has repolarized. Repolarization can begin only when the stimulus to the cell to contract or depolarize is removed. To begin repolarization chemically, the sodium and calcium channels that allowed those ions into the cell during depolarization close, shutting off the flow of these ions into the cell. Meanwhile, the potassium channels simultaneously open, allowing potassium to flow out of the cell, which allows for a rapid reestablishment of the electrical gradient needed for depolarization to occur. However, potassium is not the correct ion that is needed on the outside of the cell. Next, the potassium channels close, and specialized pumps aptly named the sodium-potassium pump in the cellular membrane work to move 3 Na+ ions out of the cell and 2 K+ ions back into the cell. At the end of this process, Na+ ions are back outside the cell, and K+ ions are now back inside the cell where they belong, and the polarity of the cell has been reestablished at –90 mV. The cell is now ready to depolarize once again.

As mentioned earlier but worth repeating, while the cell is depolarized, it cannot respond to any electrical stimulus any more than it already has. This is referred to as the refractory period. In the heart, there is an absolute refractory period and a relative refractory period. During the absolute refractory period, no amount of external stimulus will cause another contraction. During the relative refractory period, cells that have fully repolarized can and will depolarize if the stimulus is strong enough, whereas the others that have not yet completed repolarization will remain unaffected. Stimulus during the relative refractory period can cause electrical rhythm disturbances that could prove to be lethal, such as ventricular fibrillation.

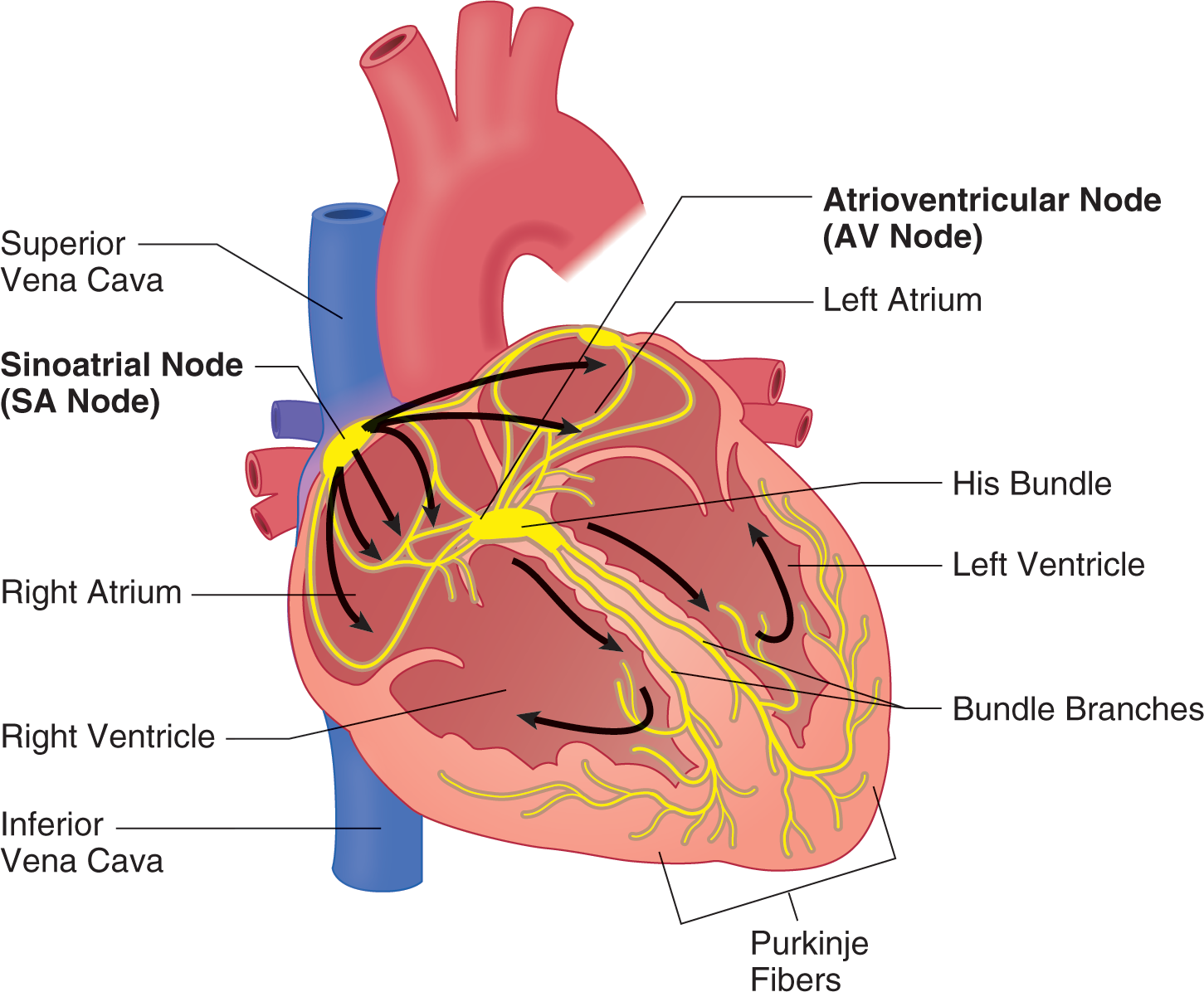

After understanding depolarization and repolarization chemically and what it means for the heart mechanically, it will now be applied to the creation of a normal ECG. When the SA node discharges, the electrical impulse travels down the internodal pathways and pauses briefly at the atrioventricular (AV) node near the AV junction. As the impulse travels through the internodal pathways, the atria are caused to depolarize and contract. On the ECG, this event is represented as the 1st upward deflection or the P wave.

The AV node then “collects” the charge transmitted through the internodal pathways and delays transmitting it for approximately 0.12 seconds, which gives the atria time to empty into the ventricles. This pause is represented on the ECG as the PR interval (PRI). When the AV node discharges, the electrical charge travels through the bundle of His. The bundle subsequently divides into the right and left bundle branches, which travel down the septum and divide further into the Purkinje fibers. The Purkinje fibers divide countless times, and each branch will ultimately innervate only a single cardiac muscle cell. This system is efficient enough to deliver the charge to every cell in the ventricles in about 0.08 seconds, allowing the large ventricles to depolarize and contract simultaneously and uniformly. This event is represented on the ECG as an upright spike called the QRS complex. The final notable part of the ECG is a hump immediately after the QRS complex, which is the repolarization of the ventricles and is referred to as the T wave.

;

; (see Figure 4-6)

;

;

, , and .

The SA node, as the pacemaker of the heart, has an intrinsic rhythm of approximately 60–100 beats per minute. This means that, under normal circumstances, at rest, the SA node will discharge 60–100 times per minute, sending its electrical charge through the normal pathway and generating what is known as a normal sinus rhythm (NSR). If the SA node fails, the rest of the heart serves as a fail-safe pacemaker, capable of taking over and maintaining the heartbeat, though usually at a slower rate. The AV node is the first fail-safe and will take over the pacemaker activities if needed at a rate of 40–60 beats per minute. In the event that both the SA and AV nodes fail, the ventricles and the Purkinje fibers will take over at their intrinsic rate of 20–40 beats per minute. This rhythm can be generated from anywhere within the ventricles and often is referred to as a ventricular escape rhythm because, by its mere presence, a person escapes death.

The heart is under complete control of the autonomic nervous system, meaning that its activities are completely regulated outside of conscious direction. The autonomic nervous system has 2 branches that are always working in opposition to each other: the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. The parasympathetic nervous system exerts its control on the heart through the vagus nerve. The parasympathetic nervous system has a slowing effect on the heart and has as its neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which acts directly on the SA node. Parasympathetic stimulation unopposed by sympathetic nervous input may result in profound bradycardia. The sympathetic nervous system is responsible for speeding up the heart and increasing its contractility, conduction, and thus the cardiac output.

One of the most common procedures a paramedic will perform is placing a patient on the cardiac monitor. This is done alike for patients with and without a cardiac condition. Although it is rather simple to accomplish, accuracy is important to be able to get the best views of the heart that cardiac monitoring can afford, especially in cases of heart attack. Cardiac monitoring will allow you to observe the electrical activity of the heart from a variety of different views and allow you to determine the rhythm that the patient’s heart is displaying. It also can allow you to figure out not only if but also where a patient is having a heart attack or other ischemic problem. This section explains everything about cardiac monitoring, including how to apply it to your patient and what the paper can tell you about your patient’s rhythm. The section concludes by delving even deeper into the normal ECG, expounding on what has been learned already.

Every patient who requires advanced care beyond the scope of the EMT–Basic will need to be placed on a cardiac monitor for continuous monitoring. This is accomplished through any 1 of the 3 standard limb leads—lead I, lead II, and lead III—but most commonly lead II. Capturing the limb leads requires the placement of 4 electrodes on the patient, 1 on each limb, hence the name. The leads are color coded regardless of the manufacturer and can be placed on the patient in any order; however, they need to be placed in the following specific locations:

The leads are placed in these locations to establish Einthoven’s triangle. Similar to a battery that has positive and negative ends, or poles, each of the standard limb leads has 1 of the electrodes designated either positive or negative, which means that leads I, II, and III are the bipolar leads. The green lead is always the ground lead, which means that it helps minimize artifact generated from skeletal muscle activity or patient motion of any kind.

Using just these 3 electrodes, the cardiac monitor is able to generate 3 alternate views of the heart, called the augmented voltage leads. These leads are unipolar leads in that only 1 of the electrodes on the patient has a true polarity. The 2nd pole is an average of the 2 remaining electrodes. The augmented voltage leads are designated by the letters aV followed by the 1st letter of the electrode that is the positive pole. For example, the lead that has as its positive pole the red lead, near the left foot, is designated as lead aVF; the lead that has as its positive pole the white lead, near the right arm, is designated as lead aVR; finally, the lead that has as its positive pole the black electrode, near the left arm, is designated lead aVL.

| Lead | + Pole | - Pole |

|---|---|---|

| I | Black | White |

| II | Red | White |

| III | Red | Black |

| aVL | Black | Average of white and red |

| aVF | Red | Average of black and white |

| aVR | White | Average of red and black |

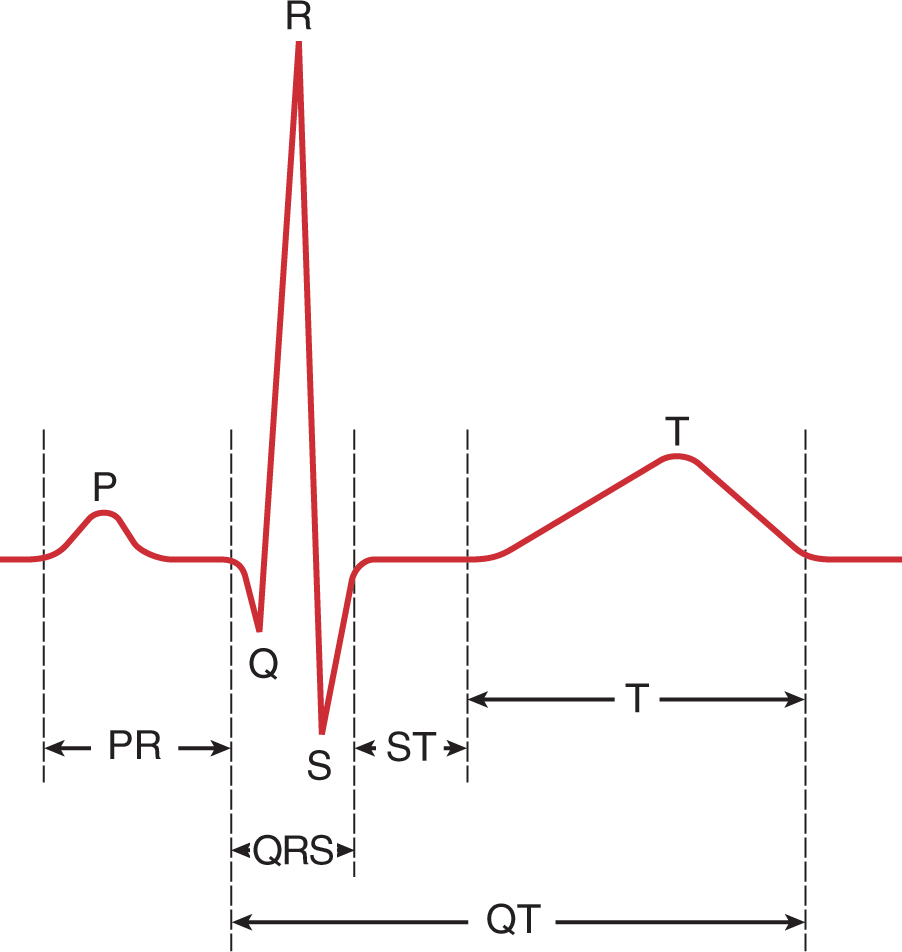

The precordial leads are 6 electrodes that are placed on the anterior and lateral left chest, basically circling around the heart. These 6 leads, combined with the 6 limb leads, comprise the 12-lead ECG, which is the gold standard in cardiology for determining cardiac events. These leads also are referred to as the V leads because they are all designated with a capital V followed by a subscript number, V1 to V6. The precordial leads are all unipolar leads that are positive at the point of electrode placement, and the negative terminal is at a calculated point of reference, which is called Wilson’s central terminal. The location and order of placement of these electrodes is specific:

All of the electrodes pick up small electrical currents traveling through the body, and the monitor converts these signals to the image on the screen and the rhythm strip on the paper. The flat part of the ECG tracing is known as the isoelectric line, and every electrical activity of the heart, whether depolarization or repolarization, can be seen as a deflection from the isoelectric baseline. If the overall direction of the electrical impulse is toward the positive electrode, it will be seen as a positive deflection above the isoelectric line. If the overall direction of the electrical impulse is away from the positive electrode, it will be seen as a negative deflection below the isoelectric line. When the overall electrical impulse is traveling perpendicular to the lead, there may be no discernible deflection at all in that lead, whereas it can be found in others. Finally, there could be a portion of time where the impulse is traveling toward the positive electrode followed immediately by a period of time where it is traveling away or vice versa. In this instance, the deflection is described as biphasic where part of it is above the baseline and another part is below the baseline.

ECG paper is designed to help you determine the rate and regularity of the heart’s rhythm. The paper moves at 25 mm per second under normal use, which means that horizontally, the paper represents time. The deflections generated by the heart’s electrical activity are vertical, which represent voltage, specifically millivolts. Each small box is 1 mm square. Two large boxes represent 1 mV; although this value is adjustable, it defaults to the 1 mV value. The small and large boxes are each necessary in discerning the time component to the ECG. Each large box has 5 small boxes. Each large box represents 0.20 second; therefore each small box is 0.04 second. It takes 5 large boxes to make up 1 second, and 15 large boxes to make up 3 seconds. At the top of the paper, hash marks represent 3-second intervals, which can help you count the heart rate. Each component to the ECG discussed previously will print out against this paper and, therefore, have normal interval ranges of which the paramedic needs to be aware in determining the rhythm.

| P Wave | |

|---|---|

| Event | Depolarization and contraction of the atria |

| Shape | Upright, smooth curve |

| Duration | <0.12 second, or 3 small boxes |

| Amplitude | <2.5 mm |

| PRI | |

| Event | Depolarization of the atria and the delay in the AV node |

| Duration | 0.12–0.20 second; 3–5 small boxes or <1 large box |

| QRS Complex | |

| Q Wave | |

| Event | If present in an otherwise healthy person, it represents the normal left-to-right depolarization of the ventricular septum. Q waves often are more indicative of an old, fully evolved infarction and are then referred to as pathologic Q waves. |

| Shape | First negative deflection after the P wave; generally pointed |

| Duration | <0.04 second, or 1 small box |

| Amplitude | <1/3 the overall height of the succeeding R wave; pathologic Q waves tend to be deeper. |

| R Wave | |

| Event | Depolarization and contraction of the ventricles |

| Shape | First positive deflection after the P wave; generally pointed |

| Duration | Because the R wave makes up the bulk of the complex, the R wave and, by extension, the entire complex should not be >0.12 second or 3 small boxes. |

| Amplitude | Could be in excess of 2 large boxes; much more than this could indicate other problems. |

| S Wave | |

| Event | Represents the final depolarization of the ventricles and is seen only when the electrical impulse is traveling away from the positive electrode. May not be present in the limb leads. A large S wave is present in V1, which should get progressively smaller with each successive V lead as the R wave gets larger. By V6, the R wave should be largest, and almost no S wave should be present. |

| Shape | First negative deflection after the R wave; generally pointed |

| Duration | Generally <0.04 second, or 1 small box |

| Amplitude | Lead dependent; could be in excess of 2 large boxes, although most often it is <1 big box. |

| J Point | |

| Event | Point where the QRS complex ends and the ST segment begins; elevation or depression of this point relative to the baseline indicates infarction or ischemia, respectively. |

| ST Segment | |

| Event | Begins at the J point and ends with the upslope of the ensuing T wave. This represents a delay between ventricular depolarization and repolarization. |

| Duration | Typically 0.08–0.12 second, or 2–3 small boxes |

| T Wave | |

| Event | Represents ventricular repolarization. From the start of the T wave to its peak represents the absolute refractory period. From the peak to the completion of the T wave represents the relative refractory period. |

| Shape | Typically upright (positive deflection) and a smooth curve; inverted or negatively deflected T waves also indicate ischemia. |

| Duration | Typically <0.25 second |

| Amplitude | Approximately 5 mm; taller, peaked, and more pointed T waves could indicate hyperkalemia. |

| QT Interval | |

| Event | Represents a full cycle of ventricular electrical activity; it is measured from the start of the QRS complex to the return to baseline of the T wave. |

| Duration | Should not be >0.44 second |