Chapter

2

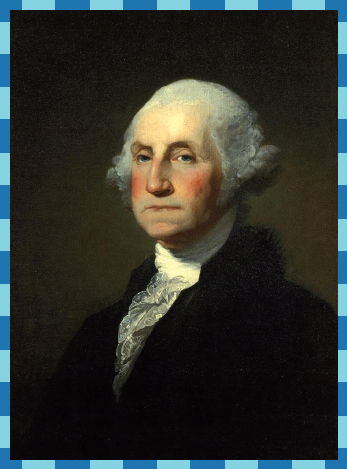

George Washington

His High Mightiness

Lived: Eighteenth century CE, America

Occupation: Commander-in-Chief, first President of the United States

How to Look Like a Hero

It’s time to take everything you think you know about George Washington and throw out at least half of it. You can start with his appearance. He was freakishly tall at six-foot, three-inches, had a pockmarked nose from smallpox, auburn (red) hair, and was built like a quarterback. The white-haired elderly gentleman we know from the dollar bill didn’t come until much later.

Washington was no dummy, though, so don’t worry about that. He knew his role in the United States of America would be too great for people not to be interested in his life. So he made sure to dot his i’s and cross his t’s. He even admitted as much when he said, “I walk on untrodden ground. There is scarcely any part of my conduct which may not hereafter be drawn into precedent.”

In other words, he knew he had better at least have the shiny veneer of a hero, unlike his actual veneers, which weren’t shiny at all.

Scary enough for Halloween.

Before he was unanimously elected as general of the Continental Army (sort of), before he led the Americans to victory at Yorktown (kind of), before he graciously came out of retirement to become the first president and set the course for the new country (somewhat), George Washington was just a small-time farm boy with no professional education and a chip on his shoulder the size of Virginia.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

We won’t even talk about the obvious fake myths surrounding George Washington, like his wooden teeth or the infamous cherry tree incident. Sure, Washington’s terrible teeth could scare a zombie, but they weren’t wooden. They were made from the pearly whites of humans and hippos. And he certainly could tell a lie. That sly old fox constantly covered up his secrets and misdeeds. His life depended on lying his red head off to Congress and to the British. Mostly because the entire British Empire wanted to kill him, and if they ever captured him or if the war was lost, Washington would have gotten a traitor’s death—hanged, drawn and quartered.

Bagging Bald Eagles

George considered it a good day when he was able to hunt. In true aristocratic fashion, foxes were his favorite prey, but he also got pretty excited when he shot five bald eagles and five mallard ducks in one day in 1768. For a man always worried about his historical reputation, bagging bald eagles didn’t faze him. Then again, they weren’t endangered yet like they are today, and the United States of America wasn’t even a twinkling in his eye.

This will never go out of style!

He also wasn’t the down-to-earth, calm hero everyone thinks he was. Washington tended more towards the pretentious side of Virginia aristocracy. Instead of shaking hands, he preferred to bow and would stare you down until you retracted your hand from his presence. Don’t even dream of actually patting him on the back, either.

And his temper was explosive when he couldn’t contain himself, although he usually could. Thomas Jefferson remembered one time in particular when George went crazy. He threw off his hat and stomped on it in a temper-tantrum most three-year-olds would envy.

George had good reasons to put on airs and fight for what he wanted. He had a lot to prove. No less than five deaths made it possible for him to become the legend we know and love. As the first son of a second wife, Washington was entitled to little of his father’s wealth. But with the deaths of his father, his older brother, his older brother’s wife, his future wife’s first husband, and his stepdaughter, Washington suddenly found himself rolling in the dough.

dough:

Money. Although his face wasn’t on those bills yet.

Without money, Washington wouldn’t have been Washington.

Hey, it takes a lot of gold to properly clothe His High Mightiness—as he once suggested a president should be called, before deciding on the more democratic, Mr. President.

Although he came from humble beginnings, George had more refinement and class in his little pinky than the king of England had in his whole palace. At least that’s what George thought. As soon as he came into some money, George made sure everyone else thought that, too.

When calling upon the Continental Congress to boycott all imported goods from Britain prior to the Revolutionary War, he was secretly ordering carriages, fancy clothing, guns, and Wedgewood pottery from London for his own personal use. At another meeting of Congress, he called for the end of slavery, then went home and bought himself some more slaves. (He preferred buying girls, so they could have kids and give him even more slaves. A sort of two-for-one deal.)

Yes, Washington was a ball of contradictions. Even in politics he wasn’t always a smooth operator. He went behind people’s backs, argued, and sulked. It wasn’t until later in life that he learned how to hide his temper under a cool exterior. Sometimes.

Puppet Master

Washington was a master when it came to fooling people. His early career is loaded with a long list of misdeeds, including:

1. Letting his men fire the shot that started the French and Indian War.

2. (Accidentally) admitting to assassinating a French diplomat.

3. Setting up a fort in a terrible location leading to its defeat.

4. And marching against a superior force, losing, and blaming it on others.

Second Continental Congress:

Representatives from the twelve colonies who gathered to complain about Britain. The Declaration of Independence was signed at this gathering too, on July 4, 1776—exactly twenty-one years to the day a young George Washington lost his first fort.

So his first command was a dismal failure. To top it off, he quit his position because he kept getting passed over for promotion. Weird. Somehow, he still came out smelling sweeter than a rose by the time the Second Continental Congress needed a military leader for their army. (To be fair, there weren’t a lot of military men to choose from. Most of the representatives from the colonies were politicians, not fighting men.)

When the French and Indian War ended, Washington was still a young guy trying to move up in a hierarchical society. After trying his hand at the military and finding “something charming in the sound of bullets” whizzing past his ears, Washington went to the dark side—politics. His first political campaign was for a seat in the Virginia House of Burgesses.

Virginia House of Burgesses:

As a burgess, Washington represented a county in Virginia. He had some power but was content to sit back and let the more outspoken (read: loud) burgesses like Patrick Henry (“Give me liberty or give me death!”) do the talking.

Mere technicalities didn’t stop George from using his imagination to gain voters. He really wanted that seat and the word “illegal” didn’t faze him. Washington didn’t like to lose, and after an embarrassing defeat in 1775, he stepped up his game in a big way. He had his supporters buy vats of wine, barrels of beer, and gallons of rum punch to help sway voters’ opinion of him. Washington wasn’t afraid to get caught buying votes. He was only afraid of not buying enough to claim victory.

He won, of course. You don’t mess with colonists and their alcohol.

To make his next move up the social ladder, he had to marry, and marry well. Luckily for him, the widow Martha Dandridge Custis was better than beautiful: she was rich and she had a thing for really tall guys.

Even though his own mother boycotted his wedding, and even though George was in love with another (already married) older woman, George and Martha ended up being a match made in a miser’s heaven. With their marriage, he came to own eight thousand acres at Mount Vernon and over three hundred slaves, but George didn’t stop there.

He was hungrier for land than a lion for a juicy zebra rump roast, and like the previous elections, employing shady dealings didn’t deter him. He secretly sent men over the invisible line dividing Indian and colonial lands to scout out prime real estate. When the British renegotiated a treaty allowing colonial expansion in 1768, Washington was ready to pounce.

It wasn’t like he was the only one grabbing the best for himself. Most colonists were land-mad. George was just better than most at underhanded dealings and secrecy, and he also had greater motivation for it. He knew that he would need to be pretty wealthy to get noticed by Congress. And he intended to get noticed.

Good Enough for Broadway

You might be thinking, Sure, George wasn’t the nicest guy when it came to getting what he wanted, but he had the undivided support from Congress and his fellow revolutionaries because his leadership and genius won the Revolutionary War. Men were practically flocking to his side!

Wrong.

The day the Second Continental Congress decided to name the head of the Continental Army, George came dressed to impress. He rolled up in his chariot and emerged in full militia uniform, despite not having been in uniform for seventeen years. Thankfully, he had a few slaves at home who were handy with a sewing needle. His strategy worked. Everyone agreed—he looked the part. Washington was now the first Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army almost by default. But A-lister looks aren’t exactly a substitute for a tactical brain.

Stud muffin in a saddle.

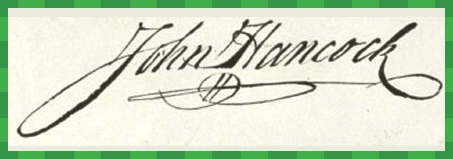

John Adams, eventually the second president of the United States, later wrote a letter stating that the “talents” that got George the general job were his “handsome face” and “tall stature.” Adams forgot to mention his own part in George’s success. See, John Adams really didn’t like John Hancock, George’s chief rival for the command of the Continental Army. Maybe it was Hancock’s obnoxiously large signature that Adams didn’t like. Everyone knew it wasn’t to make King George III take notice; it was to make Hancock popular. In order to make sure Hancock didn’t become general, Adams nominated George Washington instead.

Loud and proud.

Petty differences weren’t all that swayed the voters. Washington was from the South, and the delegates understood they needed to unite the colonies in order to beat the British. Washington would help to bridge the gap and tie the North and South together in one cause for freedom.

As he accepted the nomination, Washington said, “I do not think myself equal to the Command I am honored with.” In this case, he wasn’t being humble—he really was a terrible tactician with more “strategic retreats” than wins to date. That didn’t change in the next war. But who’s counting?

To solidify his reputation, he declined any payment. Instead, he magnanimously agreed to bill Congress for his expenses. Everything from liquor to spies’ salaries to a broom was carefully recorded. At the end of the war, Washington charged $160,074 to the new government. That’s somewhere in the millions of dollars today.

Despite being a meticulous record keeper via his thirty-two secretaries, George often found himself in debt. It might have been all those shopping sprees he enjoyed so much, but a lot of his money was also tied up in land. (He didn’t get better with age when it came to money. He even had to borrow a few thousand to go to his own inauguration in New York on April 30, 1789.)

So, he wasn’t good with gold, but what about his leadership qualities? Everyone must have liked him during the war once they realized what a good general he was. Right?

Wrong.

Washington had his army, his reputation, and his prestige. Nothing could stop him, except for the British. During 1775, Washington and the colonial army got really good at retreating. In 1776, things were going about the same way until Washington crossed the Delaware River at the end of the year and won the Battle of Trenton.

The next year, 1777, started off well for Washington and his army, with a second win at Princeton a few days into January, but then things started going downhill again with Washington racking up defeats like he was racking up a pool table. The next horrendous winter spent at Valley Forge (1777–1778), where Washington’s men starved and froze to death, was merely one low point in a year of low points.

It wasn’t just the British that wanted him dead. Even men in Congress were calling for his head. People had always groused about George’s lack of wins, his tactical faults, and his inability to see the big picture like keeping southern cities safe. George probably wondered if it was him when his aides tried to jump ship.

Truly Alarming

Despite being the poster boy for a new republic, George still had a bit of the pretentious in him. He really wanted to look elite and that meant surrounding himself with people that also looked elite. Obviously, he needed an entourage. So he formed his own personal Life Guard to follow him everywhere. They made sure he wasn’t kidnapped or assassinated, and they carried his personal papers.

It wasn’t enough that the men in his Life Guard were muscular and good at playing post-master. George had high standards down to every last plumed feather in their hats (because without a hat, a man’s appearance was just ruined according to Washington). They had to be at least five feet, eight inches tall, wear what he told them to wear, and own property. Washington spared no expense on them, but kept the group very hush-hush. It wouldn’t do for Congress to find out how expensive his kept men were. But Washington was a master of secret-keeping. He also kept an entire spy ring secret from Congress while he was general!

One aide secretly asked another general to take over the army, and Washington faced down mutiny on three separate occasions. Alexander Hamilton, future Secretary of the Treasury, pointed out that Washington was moody, difficult to work with, and had mild abilities as a leader—but they had beef, so that might all just be bluster. Hamilton also thought Washington was indispensable to the cause, if only outwardly. The man looked really good on a white horse, and looks were important.

Despite not knowing the terrain during important battles, despite being indecisive, and despite not having that spark of genius that marks most great generals, Washington was exactly what the American cause needed: a tough-as-tacks poster boy for freedom. His superhuman ability to dodge bullets didn’t hurt his image, either. Washington could come off the battlefield, his coat riddled with bullet holes, and not a scratch on him.

Somehow, even when he lost a battle, Washington still won. After the bloody Battle of Germantown (October 4, 1777), Washington lost his position and twice as many men as the British, but the French decided he was pretty brave and threw their weight behind his flailing army. (It helped that his generals were winning important battles at places like Saratoga.)

Mercifully, too, since the French were better at the whole “strategy” thing than the Americans. They had been using it against the British for a lot longer. It was thanks to French advice that the colonist won at Yorktown (1781), which was the beginning of the end for the British dream of one big Canada. It was also the beginning of Washington’s celebrity status and the end of Washington’s human status.

Casanova?

Washington had a habit of capitalizing on his good looks, like winning command of the army and charming French generals into helping the American cause. That’s because he knew the importance of looking the part. And while his marriage was a good one, he didn’t mind flirting and dancing with pretty, young girls after a few sips of champagne.

In fact, Abigail Adams, wife of John Adams, was so infatuated with him that in her letters to her husband she gushed about Washington’s goodness—and his good looks. Furthermore, Lady Kitty, the daughter of one of Washington’s generals, requested a lock of George’s hair, and Caty Greene, wife of General Nathaniel Greene, danced for three straight hours at a ball with Washington. Afterwards, she named her son after him. That must have been some two-step!

Getting Better with Age

Okay, so George wasn’t great at the whole “tactics” thing while leading the army, but he was really good at being strict with his troops. He was forever trying to make his soldiers look like soldiers—his own personal mini-me’s. He wanted them to stop gambling, drinking, and cursing. A man could get twenty-five lashes for uttering a curse word, fifty lashes for drinking, and fifteen hundred lashes for desertion. That is, until Washington had a gallows built and hanged a couple of repeat deserters as a warning to the rest of the soldiers.

Washington was constantly annoyed with his men unless they pulled off a miraculous feat, like trudging miles through snow with bleeding feet or winning against terrible odds. Then he liked them. After their shared suffering during the winter at Valley Forge—where up to ten men died a day from the cold, disease, and starvation—Washington became his soldiers’ biggest supporter. He stopped complaining about how worthless his volunteers and officers were and started defending them. He may have stayed in plusher quarters and ate dinner each night, but he knew they were miserable, and he felt bad enough about it to beg, borrow, and steal things they needed.

In time, Washington grew into his position. He gave better treatment to prisoners of war, inoculated his army against smallpox, operated a spy ring, mixed freed slaves into his army, developed a navy for the colonies, and finagled much-needed funds and arms from Congress. But it seems that the reality of the job finally hit home, and he once mentioned how he would have never taken the gig if he’d known how hard it would be.

freed slaves:

Even though Washington allowed freed slaves to fight with the army, it’s not as magnanimous a gesture as it first appears. If it had been up to him, he would never have allowed them to serve. But he desperately needed men, and the British were only too happy to arm black men for their cause. So Washington reversed his decision a year into the war, and the Continental Army was the most integrated army in America until the 1960s.

Washington may have lost more battles than he won and he was usually outmaneuvered by the superior British forces, but he held the army together, inspired loyalty in his men by his bravery, and persuaded men to reenlist. That’s no small accomplishment, no matter what kind of general you are.

First President—Kind Of

After the British surrendered and the Treaty of Paris was signed, Washington didn’t get unanimously voted in as first president, nor did he prance into the Oval Office as a thank-you for winning the war. For one, the first president to stay in the White House was John Adams (president number two), and the Oval Office wasn’t built until 1909.

Besides that, the states had to make a few mistakes at governing before Washington took the role as president. Enter the Articles of Confederation, which gave each state a ton of power and created a bunch of presidents in what was called the Congress Assembled.

It was a terrible idea. Nobody agreed and nothing got done. So that was scrapped and the United States Constitution was born in 1787. The Constitution balanced the power between the states and the federal government. It also made one person president, and that person was none other than George Washington, who was unanimously voted into office.

Now—finally!—you can start picturing the white-haired, dignified-looking Washington.

Don’t go crazy and start thinking he was the brains behind the operations. Washington knew enough to know he didn’t know enough. So he surrounded himself with geniuses, and he didn’t mind leaning on them for advice—a great tactic for once. Instead of dictating policy, like a dictator, he guided it with the wise advice of others, which became a precedent.

You don’t want to know what’s behind those pursed lips . . .

Even some of Washington’s speeches were written by others. George never attended a university, even though he really wanted to, so spelling and grammar weren’t exactly his forte. It was something that always bothered him. It also bothered one of his first historians, Jared Sparks, who went back through Washington’s old letters and cleaned up the truly horrendous grammatical errors and fancified his dull sentences.

Others helped create the myth of George Washington by gussying up details about his life. The famous painting of Washington crossing the Delaware shows George heroically standing in front of the first American flag. In reality, Washington was still flying the Grand Union during the crossing—which had the British flag in the corner with stripes across its body representing the thirteen colonies—but that didn’t seem as patriotic for the painter and the flag was changed to the new American flag.

Washington Today

Washington was lucky that there were no such things as televised debates and campaign speeches back in 1776. He never would’ve become president if there had been. He had a soft voice—John Adams sometimes had to repeat what Washington said in Congress so people could hear—and off-the-cuff questions made him nervous. Also, his dentures had the distinct possibility of falling out of his mouth whenever he spoke.

Some played up Washington’s Hulk-like physique, claiming that he threw a silver dollar across the Potomac River. Sadly, there were no silver dollars in circulation at the time of Washington’s life, and no one could do that except for the actual Hulk.

Even the infamous cherry tree story was phony thanks to Washington’s earliest biographer, Parson Weems, who apparently thought George wasn’t cool enough on his own to sell books.

The Grand Union flag: not the patriotic look they were hoping for.

Washington did accomplish a lot of real things, though. He set precedents that presidents still go by today, like only serving two terms, wearing civilian clothing, giving an inaugural address, picking his inner circle, reserving evenings for dinner parties, and retreating back home when the job got to be too much. (When in doubt, retreat!) He had to make tons of decisions not made explicit in the Constitution.

Washington set another precedent that seems to have been passed down through the years: leaving the next president with his really messy foreign problems.

Since the British were sore losers, they liked to take American sailors on the high seas and impress them—not by flexing their muscles or showing them the best Caribbean beaches, but by kidnapping them and forcing them into the British Navy. This was called impressment, and it was pretty obnoxious, but Washington didn’t plan on solving the problem while in office. In fact, Washington said sayonara, sucker to the second president, John Adams, and retired to Mount Vernon, leaving America open to another war with Britain—the War of 1812.

Paging Greatness

So for what should George Washington be considered great? Being a good leader and politician? Being the first president of a new democracy? It’s complicated since the revolution switched one set of old white guys for another set of old white guys with slightly less snobbish accents. Slaves didn’t get any more rights and neither did women.

Yet, despite Washington’s faults, who else in history has been asked to raise an army, stop a juggernaut (the British Empire), and start a new nation? And then after he succeeded, he did something kind of crazy. He gave up power not once, but twice.

Instead of riding into Congress and crowning himself emperor—kind of like Napoleon did a few years later in France—he handed in his title of military dictator. Then, Washington stepped down from office after two terms as president. This kind of thing sent a pretty strong message to the rest of the world.

True, he was sick of getting raked over burning hot coals by his one-time friends and prying media. He also wasn’t feeling well and the last tooth in his rotten mouth was gone, but he set the term limit as president at two, which has not been changed since. There would never be a king or emperor ruling for life in the United States of America.

term limit:

Except for Franklin D. Roosevelt who was elected four times, but only got to serve three before he died. After him, Congress quickly passed the Twenty-Second Amendment limiting term limits to two—just like George Washington.

In the end, maybe what made Washington appear so great (and what we still remember to this day) was looking exactly how a budding new country needed its founding father to look: majestic on a horse during war, and wise and measured on a dollar bill.