Chapter

4

Hiawatha

Incarnation of Wisdom

Lived: Fifteenth century, North America

Occupation: Cannibal-turned-Peacemaker

Scrambled Names

If you’re into nineteenth-century poetry (and who isn’t?), then you may at first confuse our Hiawatha, creator of the Iroquois Confederacy, with the Hiawatha of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem, The Song of Hiawatha. Easy mistake. It turns out that even Longfellow, the famous American poet, was confused. His poem details—in typical Romantic exaggeration—the exploits of men from the Chippewa tribe, possibly one in particular named Manabozho, but he called him Hiawatha of the Iroquois. Which is a little like confusing a New Zealander for an Aussie. Big mistake.

Longfellow thought the name Hiawatha was just another nickname for the Chippewa men. He also thought it sounded cooler and more poetic than Manabozho, which is debatable. Longfellow’s Hiawatha had lots of adventures, like slaying evil magicians and inventing writing, but eventually he saw the light and became Christian. Our Hiawatha did no such things.

So while Longfellow’s Hiawatha never existed, the real Hiawatha (possibly) did and so (possibly) did his buddy, the Great Peacemaker. Together, this dynamic duo brought peace to the various Iroquoian tribes and created the first republic—something the American Founding Fathers copied for their own republic as brazenly as a schoolyard bully before class.

cannibals:

They enjoy tasty morsels of their fellow human beings.

Through centuries of retelling his story, the real Hiawatha got lost under the weight of Longfellow’s poem and his own legends. Legends filled with cannibals and murderers. As usual, the truth has a hard time competing with cannibals. The world hasn’t known the real Hiawatha since.

Reforming a Cannibal

Before we get to the cannibals, however, you’re probably wondering how the Great Peacemaker got such an awesome nickname when his real name was Dekanawida. Well, it certainly wasn’t by killing and eating people. Even as a kid, Dekanawida refused to play any violent, war-like games. Instead, he preferred talking about his feelings and hanging out with his mom to throwing sticks at kids’ heads.

Yes, the Great Peacemaker was always destined for greatness. The prophecy at his birth even said so. The prophecy also claimed that he would bring about the end of his people, the Hurons, for his efforts. His grandmother didn’t like the sound of that and took a couple cracks at killing Dekanawida when he was an infant. Don’t worry, none of the attempts stuck, but his people still didn’t trust him. It didn’t help that he stammered when he got excited.

When Dekanawida grew up, he left the Huron people to preach peace to other tribes. His stuttering, however, squashed that dream. Through the grapevine, Dekanawida heard of a great medicine man who had lost his entire family to a murderer. In his grief, the medicine man had become a hermit. Oh yeah, he also ate people.

Before the cannibal thing got in the way, this man preached peace, just like Dekanawida. Better yet, he didn’t stammer. Dekanawida saw a great opportunity in this hermit; the bad habit of boiling limbs was just a minor roadblock. The hermit, of course, was named Hiawatha.

The Great Peacemaker sought him out, hoping to change Hiawatha’s mind and become his partner in peace, despite the fact that Hiawatha was busy stewing human limbs in his crockpot. It was definitely a strange first meeting for a couple of guys interested in peace. Luckily, it didn’t take much convincing for Hiawatha to put down the femur and follow Dekanawida into the light.

So to whom exactly were Hiawatha and Dekanawida planning on preaching? (Hint: it’s not the choir. Mostly because Christianity and their choirs didn’t arrive in North America until much later.)

Women in Charge

Thanks to culturally insensitive European explorers and their “dear diaries,” history thinks of North America as a Disney movie.

Disney movie:

The one where Pocahontas and all her animal friends canoed down lazy rivers and ran around meadows singing happy songs. P. S. Talking willow trees and pet raccoons were never normal in North America.

We imagine a pure land where the inhabitants skipped around picking berries all day, hung out with animals, and lived in bliss before the white settlers arrived.

This is false. The native tribes of North America had human problems, just like the incoming white settlers, because, well, they were human, just like the white settlers. (Although some Europeans convinced themselves those super tanned Indians might not actually be human.)

With regular problems like murder and revenge in the pure land of North America, it was up to two guys to form a multi-nation alliance between the tribes.

multi-nation alliance:

It’s hard to put an exact date on this pact, but it usually ranges from 1100 to 1660. Yes, this is a big range, which means no one knows.

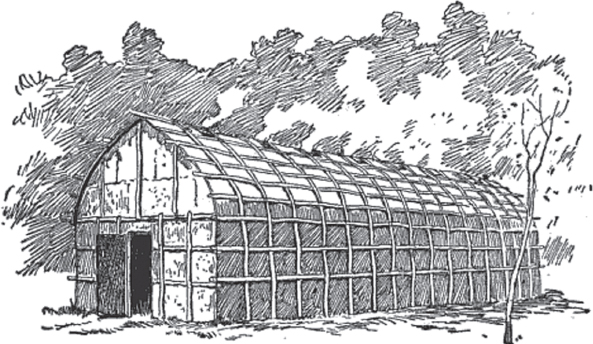

In this pre-settler time, the people living in what is now upstate New York weren’t much different than the Italians with their vendettas in the same period. Five tribes in particular were in a constant state of murder and revenge. We call them the Iroquois today, even though Iroquois is really a shared language and custom. The people who spoke it called themselves Haudenosaunee, which means People of the Longhouse. As you can probably guess, they lived in long houses.

Grandma's in charge.

Their lives centered on these longhouses, where multiple generations of one family lived in a single wooden structure. Sometimes up to sixty people lived together. Grandma lived in the front of the house, and she was always in charge because this was a matrilineal society. Matrilineal, in a nutshell, means that women tell the men where to be, when to be there, and what to do once they get there. When a man got married, he moved in with his wife’s family—at the back end of their longhouse.

The system worked out great. Men went off to war and hunted, while women got down to the business of running the village. But the relentless warfare against their fellow Iroquois was seriously getting in the way of living.

The Great Law of Peace

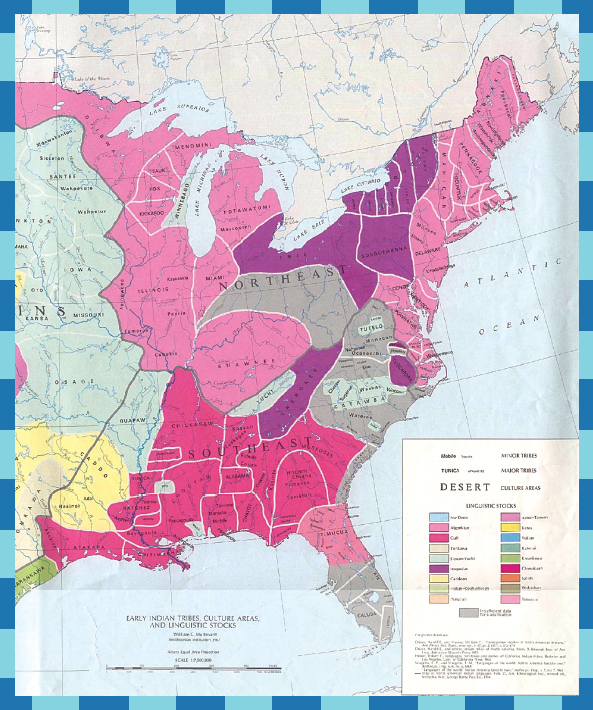

All Hiawatha and Dekanawida had to do was get five separate tribes to agree to meet at a council. The five tribes included the Mohawk, the Oneida, the Onondaga, the Cayuga, and the Seneca. History doesn’t know for sure, but Hiawatha was either a Mohawk or an Onondaga.

The two men traveled to each tribe to speak with their sachems (chiefs) and explain their plan for peace.

Each tribe could stay separate—that was most important. This Great Peace would connect the tribes through their shared culture and language, but each tribe would remain distinct. The whole point was to stop burying the hatchet in each other and bury it under the White Tree of Peace instead. (Although, before white settlers, hatchets weren’t really used in war. They killed each other with spears, clubs, and arrows.)

If a problem arose that affected all the tribes, a Great Council would be called. Each tribe would send their elected sachems to voice their tribe’s concerns. The sachems were men, but the women did the electing (and de-electing, if necessary) and before the sachems left, the women told them what to say at the meeting. The council would then collectively decide how to solve the conflict. They also would decide other things, like who they should make war on when the five tribes agreed on peace. (The Algonquins and Hurons were always a popular choice.)

The League of the Iroquois was sort of like the United Nations of today: separate nations coming together to solve shared problems—except with no nuclear weapons.

All the tribes seemed to be on board with this new league except for the sticky issue of revenge killings. If the tribes all lived in peace, what happened when someone was murdered? Fortunately, Hiawatha had an answer for this dilemma.

It’s hard to put a price on a human life, but Hiawatha managed fine enough. He figured that ten strings of wampum beads per male and twenty per female ought to cover the cost of any murdered person. An extra twenty beads would even save the killer’s own life.

laws:

Today, a reading of the Great Laws can take up to four eight-hour days. That’s a lot of laws.

Beads may not sound like a lot to you, but they were the hot commodity of the day. The beads weren’t used as money, but instead, wampum beads were traded and were used to propose marriage. They could even be woven together like a belt to tell a story, to show authority, to signify an adoption, to carry a message, or to stand as a memory aide when remembering all of Hiawatha and Dekanawida’s laws.

They were the perfect thing to give in retribution for a murder, and it was way better than an endless cycle of revenge killings.

The laws set down by Hiawatha and Dekanawida provided the foundation for the League of the Iroquois (also called the Iroquois Confederacy). The Wampum Belt showed the five nations with a line connecting them, but never running through them. Equal, but separate. The stage was set; peace was so close the two men could practically taste it.

The last thing standing in their way was a man Hiawatha knew a little too well—a nasty sort of fellow named Tadodaho, and a fellow cannibal. But the cannibal thing wasn’t the reason why Hiawatha knew him. There was no “I heart brains and hearts club.” No, they knew each other because Tadodaho had murdered Hiawatha’s family.

He struck more fear into the Iroquois than finding a worm lurking in that apple you’re about to nosh on. None of the other tribes wanted to join in the Great Law of Peace because Tadodaho promised to make their life miserable if he let them live at all. And the tribes couldn’t just give Tadodaho the cold shoulder—he might decide to eat that shoulder instead.

Dekanawida suggested that Hiawatha convince Tadodaho to join the league by talking to him. Probably because it takes one to know one, and by that, Dekanawida meant they were both as disturbed as Hannibal Lector (yet another cannibal).

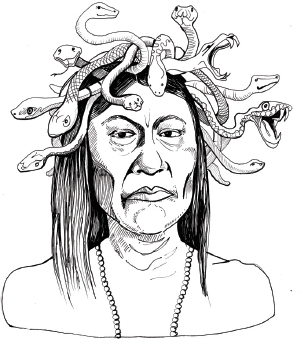

Hiawatha was understandably nervous as he and Dekanawida approached Tadodaho to discuss the league with him. According to legend, the guy had snakes living in his hair and he was munching on a victim right then and there. If the talk didn’t go well, he might decide to make them a part of the menu with a side of olive branch. Dekanawida knew he’d be fine—he was too handsome to be killed. Hiawatha, on the other hand, had reasons to be afraid, since this was the man who killed his whole family.

Practically Medusa.

Hiawatha proceeded very carefully as he approached Tadodaho. He began by using his lyrical voice to sooth the monstrous man, which got him close enough to discover the problem. Turns out, Tadodaho had relentless headaches caused by all that pent-up meanness. Since Hiawatha used to be a medicine man, he made some tea for him to drink and combed the snakes out of Tadodaho’s hair. Tadodaho, in turn, realized that he was tired of war and revenge, and of not having any friends. It didn’t take long for Hiawatha to talk him into joining their league as none other than the official host of the council—called the fire keeper.

Tadodaho accepted, and soon all five tribes were meeting at the first Council of the Great Peace. Legend has it, right after their work was complete, Dekanawida paddled out into a lake and was never seen again. Where he paddled to in a lake is anyone’s guess. Hiawatha hung around to help keep that peace alive.

It all makes for a great story, except that none of that stuff probably happened that way. Especially the cannibal parts. Sorry.

A Giant Game of Telephone

History will never know if a reformed cannibal named Hiawatha and his miraculously handsome partner, Dekanawida, ever existed in real life since their story wasn’t recorded until the late nineteenth century by Horatio Hale.

Horatio Hale:

An American scientist who studied native populations.

It’s safe to say that their names were sung around campfires in the Haudenosaunee oral tradition for centuries. Through the centuries the legends got wilder. This is probably how the cannibalism accusations got started—not because it was true, but because it sounded like it could be true, and it made the story better.

ethnologists:

People who study differences in cultures.

In fact, some ethnologists believe Hiawatha and Dekanawida represent multiple people, and they don’t mean guys with split personalities.

Instead, quite a few historical men helped the whole peace and unity thing along and through years of storytelling, they morphed into those two. It’s always easier to remember less, rather than more.

However many people it took, they made life good for the Haudenosaunee. The councils met, the sachems worked the tribes’ problems out, and all the laws were kept in memory by the wampum belts. The laws of Hiawatha and Dekanawida were passed down from generation to generation. The Iroquois could still make war on their neighbors, like the Hurons, but they had peace in their immediate territories.

Then came the Europeans—the French, Dutch, and English to be exact—and they brought all their friends to the party (not just actual friends, but smallpox, measles, guns, and rum too). The results weren’t good for the native populations.

You could say the Native Americans were decimated, but that would be an understatement. Decimated means one in ten are killed, which is a lot, but it’s nothing compared to being octodecimated, or even novemdecimated. It’s estimated that eight in ten, maybe even nine in ten, native peoples were killed in the first fifty years of continuous contact with European colonists.

Luckily for the Iroquois tribes, their influential league helped them survive the losses, mostly due to their ship-tight inner workings, just the way Hiawatha wanted it.

The council was divided into three parts. The center nation, the Onondagas, kept the council fire and hosted all the other nations. The “Older Brothers” (Mohawks and Senecas) discussed the issue until they came to an agreement. Then, the “Younger Brothers” (Oneidas and Cayugas) would do the same. If everyone agreed, the matter was sanctioned by the fire keepers, the Onondagas. If not, then the Onondaga fire keeper, named Tadodaho in honor of the original, would hear both sides and cast the tie-breaking vote. If a consensus still couldn’t be reached, then each nation agreed to handle the issue in a way that wouldn’t compromise the league.

Fulfilling a Prophecy

The Hurons—Dekanawida’s people—never joined the Iroquois Confederacy. That was all well and fine until the Dutch arrived. In order to get as many beaver pelts and other furs as possible, the Dutch traded things like guns and whiskey to the Iroquois. This created a power imbalance among the tribes, as now the Iroquois could really do some damage to their enemies, who only had bows and arrows as defense.

The Mohawks and Senecas attacked the Hurons while the Hurons were recovering from a smallpox epidemic—in the middle of winter, no less. The Mohawks and Senecas were mad that the Hurons had been secretly making treaties with the Cayugas and Onondagas behind their back. The sick Hurons didn’t stand a chance. A few villages put up resistance, but it didn’t take long for the Huron nation to run for their lives. Most died, some escaped to other tribes, and others were actually adopted by the Iroquois.

And so, ironically, Dekanawida’s great peace plan, the Iroquois League, ultimately destroyed his own people, just as his grandmother knew would happen.

Despite the natives’ plummeting populations during this time, the Iroquois Confederacy remained powerful. They mowed down their enemies and adopted survivors as their own. Soon, they were in control of upstate New York and parts of what is now Canada, about forty thousand square miles. It sounds like a good thing, but it turned out to be not so great. Mostly because it isn’t hard to spot a giant. Same goes for the Iroquois. Once the Europeans had the tribes in their sights, it didn’t matter how geographically strategic their locations were, or how well their councils worked. They were doomed.

Opposites Don’t Always Attract

The white settlers and native populations were about as different as video games and hide-n-go-seek. Communal farming was the way of life for the Iroquois. To the settlers, land was for individuals, and the more land one had, the better. Their dictionaries had different definitions of pretty much everything, to be honest.

Purple marks the spot.

When the French and Indian War rolled around (1753–1763), the Iroquois backed the English. Contrary to its name, the French and Indian War wasn’t actually between the French and the Indians. Rather, it was a war between the French and the British with different Indian tribes supporting either France or Britain.

For centuries, these two European powers hadn’t seen eye to eye. More like knife to eye. North America was just the latest place to take their battle. The British won, thanks largely to the Iroquois, and the French retreated. Instead of New France, New England survived.

During these wars, the Iroquois absorbed other tribes and refugees devastated by all the diseases and fighting, like the Tuscaroras. Now there were six tribes in the Iroquois Confederacy and all of them formed one really bad habit. No, not picking their noses in public and dining on boogers. The tribes had absorbed colonist culture over the years, making the entire Iroquois nation dependent on the settlers for things like flint, wool blankets, and guns. Even the wampum beads were worthless after white settlers started using machines to make porcelain beads. This is where it gets bad.

After years of trading, the white settlers wouldn’t accept wampum as a form of payment and that left the natives with nothing to trade except their land, which dwindled away. The giant was slowly dying.

Then came the death blow. You can call it the American Revolution. The Iroquois League was divided, unlike the colonists who were finally united in something—their hatred of Britain. Some tribes wanted to continue supporting the English, who treated them marginally better than the American farmers. Most wanted neutrality, but British and American agents made that impossible. And despite their tight-fitting breeches and bug-infested powdered wigs, those white men were really good at killing.

The League split like a log, which was exactly the opposite of what Hiawatha would have wanted. The Oneidas and some Tuscaroras sided with the colonists, but the rest backed the British, and we all know how that turned out. Backing a loser is never a good thing. When the British got booted from the colonies, it was only a matter of time before the longhouse people followed.

One illegal treaty after another deprived the Iroquois of their ancestral lands. The colonists’ terrible idea of a thank-you included taking land from the tribes who sided with them and slaughtering the tribes who didn’t. Nothing gets a message across like a few balls of fire rolling toward a wooden home.

Most Iroquois got the not-very-subtle message and retreated to Canada and northern New York, where the Iroquoian reservations to this day function under the laws of Hiawatha and Dekanawida’s legend. After centuries of power and peace, the Iroquois had lost everything—except their belief in the laws set down by their heroes.

White Men in White Wigs Always Get the Credit

How much did the league and its Great Law actually influence the fledging United States government? The two entities are obviously similar, but it’s still an ongoing debate. Benjamin Franklin did say, “It would be a very strange thing if Six Nations of Ignorant Savages should be capable of . . . forming such a union . . . and yet such a union should be impractical for ten or a dozen English colonies.” That’s what you call a double whammy. Not only were the Iroquois considered “ignorant savages,” but the colonists were even more ignorant for not being able to do what the Iroquois did.

Eventually, Thomas Jefferson took up the banner. He plucked ideas from the English Bill of Rights, Common Law, and ancient Greece and Rome. He wove them together to create something new. But the colonists also took cues from the Iroquois, such as representative government, checks and balances of power, the importance of a constitution, and interpreters of the law for their own government. So while many ideas and people influenced the United States Constitution, it’s important not to overlook the importance of Hiawatha’s vision and how it relates to our current government.

Jefferson wasn’t the only white man cherry picking all of the good stuff about the Iroquois Confederacy for his ideal government. All the way across the pond, two German philosophers, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, were also intrigued by reports of the Iroquoian way of life.

Their reaction was sort of the opposite of what most white men thought. Community living and sharing? Sign them up! So they each wrote a book on how everyone should live closer to the Iroquoian ideal of life.

A few years later, some Soviet leaders decided to model the new Russian government off of these books (and, as such, off the Iroquois). That means that two future rivals—the United States of America and Russia—both drew inspiration for their government and their societies from the Iroquois Confederacy.

Thanks, Hiawatha. Even if you weren’t a cannibal, and even if you weren’t real, the stories about you were real enough to change the world.

Roman, European . . . It’s Uncannily Similar

Europeans in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries liked to categorize civilizations according to how similar they looked to their own people. On the totally made up scale of “civilized or not,” they ranked people either “savage, barbaric, or civilized.” If you had servants to prop up your feet whenever you rang a bell, congratulations! You were civilized. If you lived in a communal housing situation and shared everything like the Iroquois, well you were still in the “savage” stage of development.

At the time, people used these theories to explain why some people (Europeans like themselves) were better off than other people (Indians and Africans like the ones they conquered). They must not have noticed all the poverty and misery in their own societies from their darkened carriage windows.

As bad as that sounds, they weren’t the first to rank people. When the Greco-Roman travel writer/geographer/historian, Strabo, explored the world in the first century BCE to the first century CE, he based a people’s moral worth on how much Roman civilization they had. Less Roman influence equaled less worth. Some things never change.