Chapter

6

Major William Martin

Operation Mincemeat

Lived: 1943, Britain

Occupation: Fake Dead Mailman during World War II

Every Good British Spy Story Needs a Little James Bond

No one expected a corpse to change the course of World War II, but then again, no one expected a dead man to be promoted to major in the British army, either. Desperate times call for desperate measures, and World War II was desperate times.

It was none other than Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond, who helped the Allies invent one crazy (the British would say barmy) deception scheme after another. At the outbreak of war in 1939, Fleming worked as a personal assistant to an admiral. (Hardly a glamorous job for a would-be famous author, but Fleming made the best of it by later turning all of his superiors into characters in his novels.) Together, he and the admiral drafted a top-secret document nicknamed the “Trout Memo,” which is a weird name when you think about it. Inside, the dynamic duo listed fifty-one ways to trick the enemy.

As anybody who has ever seen a James Bond movie knows, Ian Fleming had a fertile mind. Today, one might call it an overactive imagination. Most of the ideas in the “Trout Memo” were too flashy—and others, plain crazy. But one idea in particular, #28, hit just the right note. Appropriately, Ian Fleming entitled it: “A Suggestion (not a very nice one).”

Idea #28 was ambitious and bold. In order for it to work, the British and Americans would need cover stories for their cover stories. They would also need near perfect planning. But if they pulled it off, #28 could change the course of the war. And no one but the Nazis wanted to spend the rest of their lives saying “Heil Hitler.”

“Everybody But a Bloody Fool Would Know It Was Sicily”

The war wasn’t going as well as the Soviet Union, Britain, and America had hoped by 1943. Despite their super catchy, super cool nickname—the Allies—there were still dictators running roughshod all over Europe. The Allies needed to end the war soon, and taking the fight to Hitler’s doorstep seemed the best way.

When trying to break a strong chain, it’s always best to go for the weakest link. In this case, the weak link was with Hitler’s Fascist friend and Italy’s dictator, Benito Mussolini. Together with Japan, Hitler and Mussolini were the Axis Powers—another catchy nickname. The Allies wanted to invade Italy first, and to do this, they needed to secure Sicily—that funny-looking island always getting kicked around by Italy.

The Axis Powers used Sicily as a base for German Luftwaffe bombers to launch surprise attacks on the rest of Mediterranean Sea, destroying anything that flew or floated past. It was a real problem, and if Britain and America intended to win the war—and they did—they needed to secure Sicily and smash those death-dealing bombers. The Allies just needed to convince the Axis Powers that they weren’t going to do exactly that.

England’s Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, even quipped, “Everyone but a bloody fool would know it was Sicily.” And even if Hitler and Mussolini were dumb as dirt, they would catch on rather quickly when 160,000 Allied troops started assembling in that general area. Something like that is hard to miss.

Don’t be a bloody fool.

So the British generals realized they needed a daring plan. In order to gain the element of surprise, they needed to pretend their next target wasn’t Sicily by pretending that it was Sicily.

Confused yet?

That’s where Ewen Montagu entered the story. Despite the fact that his own brother was a Russian spy, Ewen Montague loved his country. He drank his tea, ate his crumpets, and served as a British spy. He also realized that idea #28 would be a perfect fit for the Sicily invasion. Of course, he later claimed that he didn’t get the idea from Ian Fleming’s memo, but that’s all in the past now.

So, what was idea #28, this not very nice suggestion?

Number 28 called for the Allies to use a dead body as a fake spy in order to plant false information in the mind of the enemy. Bogus spies were nothing new in WWII. Legions of fake “sub-agents” roamed Europe, “operating” under the employ of real spies. Having hundreds of fake spies running around distracted the enemy from the real spies, and they also helped validate false information. As you’ve probably noticed, spying isn’t just about stealing secrets or keeping secrets safe. It’s also about getting the enemy to believe things that aren’t true. That’s called disinformation, and #28 is a perfect example of that.

disinformation:

Intentionally leaving a false trail.

According to the plan, a corpse would wash up on a beach, presumably after a fiery plane crash in the Atlantic. Attached to the corpse would be documents of a sensitive nature. These top-secret letters—fake, of course—would refer to a plan to invade Greece, but they would also joke about using Sicily as a cover-up.

If the scheme worked, the Germans would get a hold of the letter, re-divert troop strength to Greece, and leave Sicily wide open. Not only that, but the Germans would see any build-up of American and British troops around Sicily as a trick—as part of the “cover-up” referenced in the letter. That would allow the Allied Powers to prepare for their real attack on Sicily without any suspicion on the enemy’s part.

Faker than a $3 bill.

As the finishing touch, Ewen Montagu dubbed their plan Operation Mincemeat, since, well, the corpse was kind of like mincemeat pie, minus the flaky crust.

And the Plot Thickens . . .

Before the British could put the plan into action, there were plenty of hurdles to overcome. First, Operation Mincemeat needed a good corpse, which was harder to come by than you’d think during a war where over 60 million people died.

Sure there were lots of bodies—just not the perfect body. The corpse had to be a man who was freshly dead and young. He also had to look like he belonged in the military, but he couldn’t have died in combat. They needed the Germans to believe that he had died in a watery plane crash.

Also, he couldn’t have any family back home. Mothers typically want those bodies back. A suicide would work—there were plenty of those in Europe during the difficult times of World War II—but most methods, such as ingesting chemicals and hangings, would be discovered during the inevitable autopsy.

autopsy:

Cutting open a body after death to figure out how they died.

Luckily for the British, a slightly deranged Welshman named Glyndwr Michael swallowed enough rat poison to kill himself in January 1943. Rat poison, you see, is undetectable in hair samples after death, unlike arsenic and other types of poison. The Germans would never know that’s how the man really died.

Ewen Montagu and team put the corpse on ice and began working on the next step in the plan—creating a fictional man to go with the body. He and his staff flipped through their war files and found a name: Major William Martin—a real British pilot. It had a certain ring to it, they decided. They bought the corpse a sharp uniform and took pictures for his ID.

Dead men aren’t exactly photogenic, so they got a guy in the office to pose for Major Martin’s ID card.

Just in case the Germans looked into Major Martin’s past, they even made up a fake engagement between him and a real woman and put it in the papers. Luckily for her, she didn’t have to go on any real dates with him.

Finally, they assigned the major to the Combined Operations. His new role: to transport the personal letters of Lieutenant General Archibald Nye. Now, it wouldn’t look suspicious when the Germans found the officer’s letters attached to Martin’s arm.

Meanwhile, the real Major Martin didn’t have a clue. He spent his days in Rhode Island, teaching the Americans how to fly, which was probably for the best. That way, he’d never hear about his name being used, which he might not be so keen on. Sure, there was the small issue of his death notice, which would probably appear in the local newspapers back in Britain. His friends and family would believe he had died. Maybe they’d even hold a funeral for him. But Ewen Montagu and his team figured they could clear all that up after Operation Mincemeat succeeded. After all, this was war, and sacrifices had to be made.

After all the difficulties finding a suitable corpse, it should have been smooth sailing once one was located. But after three months on ice, the body didn’t feel like cooperating. Glyndwr Michael’s feet had frozen solid at right angles, which was quite unfortunate when it came time to put on his new boots. Try putting on a boot. The ankle needs to move, but frozen ankles aren’t exactly bendy. Montagu’s team came up with the idea to defrost just the ankles, slam the boots on, tie them up, and hope the feet didn’t fall off. The corpse itself was a little worse for the wear after three months in deep freeze. The eyes had sunken, and the skin had turned yellow. Glyndwr was also skinnier than any British soldier they’d ever seen. But at that point, all they could do was cross their fingers and shove the body in the canister.

Next, Montagu’s team set about creating the fake letters that would be found on the body. Montagu didn’t waste time agonizing over them. Actually, he quite enjoyed impersonating Nye. It was everyone else that objected. Montagu filled his letters with corny jokes. He found himself hilarious, but everyone else pointed out the obvious—generals don’t joke and the Germans had to believe the letter was legit.

After months of countless edits and rewrites, the team finally came up with a solution. They asked Nye himself to write the letter. One would think that a team of creative geniuses would’ve thought of that earlier, but they were probably overworked and underpaid. As everyone but Montagu suspected, Nye made no jokes. It’s probably for the best, since the Germans wouldn’t have gotten the jokes anyway.

The letter now had everything it needed including authority. As a finishing touch, the British added a body part to the letter—an eyelash, to be exact. It sounds strange, but the British included one in every letter they sent. Cliché today, but effective during WWII.

Even if the German spies managed to get their hands on a letter and open it, they wouldn’t notice the eyelash hanging out in the folds, looking as innocent as a newborn baby. The German spies would re-seal the letter and send it on, thinking they were pretty smooth. Once the Brits got their letter back, that missing eyelash would tell them everything. They’d know that the letter had been read and the information inside compromised.

Now that they had a finished letter and a well-dressed corpse, the team turned to the final problem: where to drop the body? Spain was the obvious choice. Although it was neutral during World War II, it had plenty of German sympathizers and spies that would bring the body to German authorities. The Spanish were also Roman Catholic, meaning they hated autopsies. A few cuts, and they’d be done—nothing too invasive, which was exactly what the Brits wanted.

But Ewen Montagu and his team had to be careful. Spain also had its British sympathizers. What good would it do for the corpse to be handed back to the British with nothing more than a smug grin and a “de nada, amigos”?

Finally, Montagu’s team decided to drop the body in the town of Huelva, Spain—a spider’s web of German spies and sympathizers. It helped that Germany paid members of the town quite well to keep an eye on British ships passing by on the ocean. That extra cash in the pocket made saying, “Heil Hitler!” a little easier. Thus, the plan was ready to be set into motion.

It’s a Go!

Winston Churchill gave the thumbs up, and a date for the drop was set. The Brits even let American General Dwight D. Eisenhower in on the gag, since he ran Allied operations in the Mediterranean.

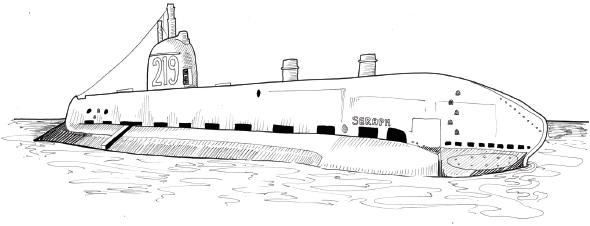

Montagu’s team filled a metal canister with twenty-one pounds of dry ice and stuffed the corpse inside with a bit more dry ice for good measure. Attached to its arm, they chained a briefcase with the fake letters inside. Then, they sealed the canister and put the whole package in a submarine, the HMS Seraph. No one but the officers on board knew the canister’s actual contents. Most of the sailors thought it was meteorological equipment. A few even used the canister as a pillow. They probably had some weird dreams.

The fastest way to deliver a “present” in WWII, including corpses and torpedoes.

Secrets Revealed—Decades Later

The body of Major Martin was buried in Huelva, Spain, shortly after its discovery. For years, the identity of the corpse remained a mystery. Finally, in 1996—over fifty years after Operation Mincemeat—an amateur historian found a document with Glyndwr Michael’s name on it. To honor his contribution after death, a small note was added to Major Martin’s grave in 1997. It reads: “Glyndwr Michael served as Major William Martin.”

What else came out over fifty years later? The commanding officer on board the HMS Seraph “forgot” to mention in his report that he had to use explosives on the canister. In fact, he didn’t come clean until 1991.

Early in the morning on April 30, the submarine surfaced just outside of Huelva at the drop-off site. The officers pried opened the canister and tried not to puke at the stink. Even though it wasn’t part of the plan, they said a quick prayer over the body before pushing it into the water, where it bobbed its way to shore at 4:30 a.m. It all went off without a hitch.

The canister, on the other hand, was a different story. The soldiers needed to sink it in order to hide the evidence, but it refused to go down. Complicating matters, Spanish sardine fisherman were already out, casting their nets in the distance. If they saw a submarine poking out of the water, it would all look pretty suspicious.

The officers considered their options. The sun was coming up and time was running out. They needed to sink that canister! So, they pumped it full of bullets. When that didn’t work, they crossed their fingers, threw an explosive in the tank, and dove under water. The bomb maybe lacked finesse, but it was just enough to sink the cargo.

It didn’t take long for the body to turn up on shore. One lucky fisherman found it that morning—the explosions and gun shots from the submarine officers probably helped. The British were quickly notified of the dead soldier, but so were the Germans. Now the Brits needed to stall. They had to appear as if they wanted the body back ASAP, but what they really wanted was for the German spies to get there first.

“Mincemeat Was Swallowed Whole”

German spies scrambled to get the briefcase, but unfortunately, it ended up in the hands of the Spanish Navy—and let’s just say that the Spanish Navy wasn’t a big fan of the Germans. At first, it looked as if the plan had failed, that the Spanish Navy would hand the briefcase right back to the Brits, exactly as Montagu feared. But then, at the last minute, the Spanish government’s slow bureaucratic system saved the day—maybe the first and only time red tape was a good thing.

red tape:

Piles and piles of paperwork.

Due to all the paperwork and forms that had to be filled out for a newly recovered dead body, it took twelve days for the briefcase to get handed back to the British. That delay gave the German spies just enough time to work their magic. They pressured the Spanish to hand over the papers. They got an hour, which was all the time they needed to make copies.

Even better, the documents ended up in the right man’s hands—Major Karl-Erich Kühlenthal. Major Kühlenthal was a quarter Jewish, something that could get a man killed in Nazi Germany. So maybe he wanted to impress his Nazi bosses with his great find. Or, maybe he was just a bloody fool. Either way, he didn’t question the letters. He personally carried photocopies of everything straight to Germany, where it was just the morale boost Hitler needed after losing Africa.

See, the best way to dupe someone is to use things already in their minds—your enemy’s fears and desires. The Germans wanted to believe that they had found top-secret documents, so they did. Anyone who didn’t believe the letters kept quiet. Hitler was a dictator, meaning he could pretty much do whatever he wanted, and he wasn’t exactly a people person. Good in front of large crowds, yes, but a loose cannon one-on-one. And no one wanted to end up on the wrong end of that cannon.

Really, though, things didn’t add up and the Germans should have been a bit more skeptical. There were no other bodies found and no wreckage. If the corpse came from a plane crash, how come nothing else had washed ashore? Plus, the body looked as if it had been dead for months, which it had. But instead of putting the pieces together, the German Intelligence explained it all away. They told themselves that the wreckage sank, that the other bodies were eaten by sharks, and that the sun’s rays accelerated the body’s decomposition. Anything to make the story make sense.

After Major Kühlenthal made copies, he had the letters expertly resealed and handed back to Spain, but with one minor oversight. There was no eyelash. When the Brits finally got their letters back, they knew that the German’s had seen their fake plans. The British authorities sent a telegram to London. It read: “Operation Mincemeat swallowed whole.”

Within a month, Hitler transferred much of his power to Greece. He stationed torpedo boats off-shore and built batteries and minefields along the coast. Then his army settled in and waited for the attack.

It never came.

Even after the Allied Powers began their invasion of Sicily, the Germans refused to budge from the Greek shore. Due to Operation Mincemeat, Hitler believed that Sicily was just a cover for an even bigger assault on Greece, and he wasn’t going to let those crumpet-loving Brits fool him!

How One Fake Spy Can Change a War

Though the invasion of Normandy on D-Day would eventually overshadow it, at the time, Sicily was the largest amphibious landing in the war to date. The Allies came out swinging, striking the enemy on their own land. And thanks to Operation Mincemeat, it went a lot better than it could have. Instead of taking ninety days, as the Allies originally thought, the offensive only took thirty-eight. Also, out of the 160,000 Allied men who went into battle, 153,000 survived. Italy surrendered in September, and its dictator, Benito Mussolini, toppled off his fascist perch.

offensive:

The Allies nicknamed this invasion Operation Husky, which has no connection to Sicily at all—just the way they wanted it.

Even better, Hitler was so embarrassed by the double-cross that he became paranoid. When his spies found real top-secret documents only a few months later, he ignored them, afraid of another Mincemeat debacle.

Of course, Operation Mincemeat didn’t single-handedly end the war, but as one well-placed nail in the coffin, it certainly helped. All it took was a real man’s name and a dead man’s body to create a fake spy who changed the course of the war.