Chapter

7

William Shakespeare

To Be . . . Or Not

Lived: Sixteenth century CE, England

Occupation: Actor, Playwright

Master? Or Monkey . . .

To be or not to be? Shakespeare probably never imagined people asking that question (and one of his most famous lines) about him, but then again, maybe he should have. Being the most famous English writer of all time comes with a price. In this case, the price is being called a fraud.

Perhaps it’s because when it comes to Shakespeare’s real life, there’s less to go on than a fake treasure map. Actually, a fake treasure map might be more helpful than what’s known about William Shakespeare’s life.

What? You thought the most brilliant playwright in history left behind stacks of plays, poems, and letters? You wish. The world doesn’t have so much as a couplet in Shakespeare’s own hand, only six shaky signatures on legal documents that look as if a trained monkey could’ve penned them.

No wonder the world’s largest literary manhunt turned into a wild goose chase long ago.

That doesn’t necessarily mean Shakespeare the playwright never existed, but you’ll have to decide for yourself. Don’t worry, there’s only about a billion books written on the subject if you really want to do some investigative journalism.

“There’s no more faith in thee than in a stewed prune!”

–“Shakespeare’s” play, Henry V

Party Like a Rock Star

Shakespeare’s story is the stuff of legends, which is maybe why it could be nothing more than one. When does a genius son of a failing glove maker morph from a country kid to a big city hot-shot? And when would he have time along the way to write the greatest plays in the English language and rubs elbows with the likes of Queen Elizabeth? Only in the story books.

So let’s start at the beginning. Will Shakespeare was born in Stratford-upon-Avon, a small town located about one hundred miles west of London.

His father was a successful merchant. He also held a number of official positions such as the town bailiff—a kind of local mayor. Things started out well for the Shakespeares. They weren’t royalty, but they weren’t starving either. Then, Will’s father got in trouble with the law. He became a dealer of the hottest Elizabethan commodity. Yes, Shakespeare Senior let all that bailiff power go to his head and got into the illegal wool trade, which was a lot riskier, and more dashing, than you’d think. At least, Shakespeare’s mom thought so, since she had six kids with Shakespeare Senior.

Shakespeare’s birth house oozes sublimity.

Getting caught was enough to sink the family’s fortunes and force Will to drop out of grammar school, probably to help his father make gloves.

grammar school:

Kids started grammar school around age seven in Elizabethan England, where they were taught to read and write, and learn dead languages like Greek and Latin by force.

At the age of eighteen, William married Anne Hathaway who was twenty-six and pregnant. Today, it could be a reality show, but back then it was just life. Around one-quarter to one-third of all women who got married during this period were already expecting a child when they said, “I do.”

Small town life didn’t suit Will, though. Instead of staying home and caring for his wife and three small children, he hitched a ride with a traveling theater company to go play dress-up. Shortly after, Will hit the big time. He produced 39 plays and 150 sonnets. He traveled between Stratford and London, managed a theater company, and was an all-around rock star. He lived the glamorous life, eating caviar and sipping champagne. He was a genius, and luckily for the world, even his poop came out in golden letters.

Eventually, he retired at a ripe old age (his late forties) and died in Stratford on his fifty-second birthday. And the world has loved him ever since.

At least, that’s the version we’ve been led to believe all these years.

Where There’s Smoke . . .

There are a lot of problems with the story we’ve been told about William Shakespeare. First of all, it doesn’t make any sense. Running away from home to become an actor was not considered okay in 1580s England.

actor:

Called a player in those days.

Today, actors are fawned over as celebrities and hounded by the paparazzi, but back then, they were about as cool as a hot steaming pile of horse poo.

Being an actor wasn’t even considered a real job. Since they wandered from town to town giving shows, their official occupation was vagrancy, and vagabonds could be arrested, whipped, and branded. This was to ensure that they kept the peace, because who knew when they might break into song and dance—the horror of it! So why would a man give up a respectable trade, like being a glove maker, to become an actor?

The second problem with this story is that it really doesn’t make sense. (Yes, that’s the same as the first reason.) Shakespeare’s works display more knowledge than C-3PO’s programming. A true Renaissance man, Shakespeare the playwright seems to have an intimate grasp of Elizabethan court life as well as life at foreign courts. His work also shows him to be a master of military terminology, astronomy, mathematics, languages, Classics, law, art, literature, medicine, music, and more.

This poses a big problem—like an eight-hundred-pound gorilla in the room problem—because there’s no record of the historical William Shakespeare having attended any school let alone a university. (However, if he actually went, Elizabethan grammar school wasn’t like your middle school today. Students either learned their Latin conjugations or it was beat into them with a nice-sized stick.) Although it’d be weird for a bailiff’s son not to get some schooling, so most people assume he went for a little while.

So where did all the other learning come from? All that court life know-how had to come from somewhere. Proper bowing techniques and other persnickety protocol wasn’t the sort of thing Shakespeare would have been taught in grammar school, and even a genius can’t pluck that kind of stuff out of the ether.

There’s also no record of Shakespeare ever meeting the queen, living at court, or traveling the world—and this was a time of meticulous record keeping. We have records showing how many times Shakespeare evaded taxes (four times), how many times he tried to sue for petty sums of money (three times), and how many times he was caught hoarding food during a famine (once), but nothing about him meeting Queen Elizabeth. Seems kind of strange, doesn’t it?

Perhaps a lot of this could be explained away, like pointing out that Shakespeare’s vast knowledge could have come from reading books or that he didn’t have to live at court to know its rules. He just had to ask a nobleman a few haughty questions like, “You sir, how dost thou bow?” and he’d know how low to go. One could also argue that he wasn’t actually considered a rock star until after he died, so nobody ever thought to save his to-do lists to hawk on eBay.

But the more you dig, the more you realize there are serious problems with each of these explanations. If Shakespeare were self-taught, for example, he would need to have a huge library of books. Where are they, then?

Lost Years

No one knows what became of the historical William Shakespeare from his twins’ birth in 1585 until he pops up again in London in 1592. There’s less evidence of what he did during these “lost years” than evidence of Sasquatch. At least there are a few grainy photos of the monster.

For all we know, Shakespeare could have been in Italy, mastering the art of being a gentleman, or traveling the world, becoming savvy in stars (and star-crossed lovers). Maybe he even spent a year in a law office absorbing all that lawyerly wit. But without evidence, that could all just be hogwash. And that’s why they’re called the “lost years.”

In Shakespeare’s will, he details everything he owns, down to his “second-best bed,” leaving them all to various people including his wife and fellow players. No books were mentioned anywhere in his will.

Books were expensive possessions back then. If Shakespeare had owned any, he wouldn’t have forgotten to include them. In fact, there’s no mention of him having a literary career at all in his will, and even his name is spelled differently than on his plays, when his name was written at all. One would think he would have wanted to preserve his literary legacy, and having the name “Shakespeare” written down would be the first step. It’s all about branding! But does that mean the world has gotten played by the player?

Because we have the plays (which are undeniable) and because so many questions surround the life of the historical William Shakespeare from Stratford-upon-Avon (also undeniable), two camps have formed about his credibility as the playwright.

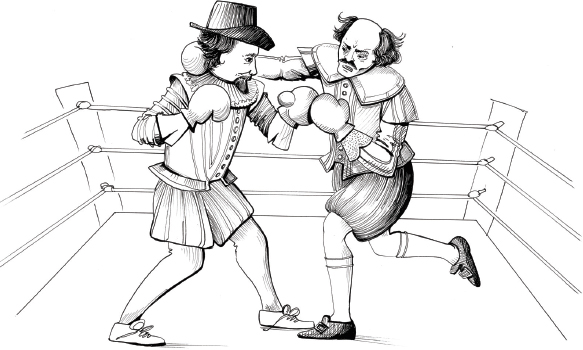

On the one side, there are the Stratfordians, who believe that the historical William Shakespeare from Stratford-upon-Avon wrote Shakespeare’s plays. On the other side, there are the Anti-Stratfordians. These individuals believe that a man named William Shakespeare existed, but that he wasn’t the self-taught genius of legend. The Anti-Stratfordians think he was an actor, possibly half-witted, and the front man for the real writer of the greatest plays in the English language.

How did all this doubt start?

Fighting words in Elizabethan times: “Your brain is as dry as the remainder biscuit after voyage.” –“Shakespeare’s” play, As You Like It

It wasn’t until the literary world made Shakespeare out to be the English god of really good writing that anyone took a step back and scratched their thick beards.

See, a contagious idea called bardolatry spread through the nineteenth century as quickly as the plague spread through the sixteenth century. This was the time in which Shakespeare became a god. Literary snobs who worshipped Shakespeare’s plays knew they were deeper than the ocean. Obviously, they must have been written for the high-class thinkers (like themselves). So instead of remembering his true origins, people began to worship him as the most intelligent human being to ever grace the earth.

Then, a guy named Samuel Mosheim Schmucker brought that house of cards tumbling down—accidently. Schmucker didn’t like the way people had begun to doubt the existence of Jesus Christ, so in 1848, he wrote a book. He aimed to show everyone just how very foolish it was to doubt a man’s existence just because he was born to a poor, lower class family, had little formal education, and left behind no historical records. Look at Shakespeare! He only left behind legal documents, but he was still a god of writing.

From Bear-Baiting to Theater-Going

Despite the inherent snootiness that comes to mind when you think of Shakespeare’s plays, they were pretty much the opposite in Elizabethan England. People didn’t break out their furs and monocles to go to the theater in Shakespeare’s day. Instead, they filled their pockets with rotten fruit and their bellies with beer. Then they stood jowl-to-jowl, hooting and hollering throughout the performance.

Shakespeare’s plays competed with bear baiting for its audience, which wasn’t exactly highbrow entertainment. In bear baiting, a bear was chained to the ground while dogs attacked it. As the dogs died, a new one replaced it until the bear died or people ran out of dogs.

Nobles also attended plays back then, but they sat above the riffraff. Thus, playwrights had to write stories that appealed to both classes. Shakespeare’s theater company, the King’s Men, was able to do both. That’s why they thrived in the common theaters like the Curtain and the Globe, and were also invited for special performances at Whitehall for royal eyes and ears.

Schmucker’s plan backfired. Instead of convincing people that Jesus was real, people started questioning Shakespeare’s existence too. Whoops.

Now that Shakespeare’s existence was called into question, those snobby elites remembered something else. The bard known as Shakespeare never went to Oxford or Cambridge—or anywhere else associated with higher learning—and the backlash began. Poor Shakespeare went from being dead, to being a near-god, to never existing in the course of a few decades. People started wondering how a self-educated son of a glove maker penned the greatest works of the English language when his signatures showed his writing wasn’t exactly “Shakespeare.”

The first alternative candidate to be proposed as the real Shakespeare was none other than Sir Francis Bacon, inventor of the scientific method. Leading the Baconian charge was a woman named Delia Bacon.

With the help of illustrious friends like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Samuel Morse (inventor of the Morse code), Delia Bacon traveled from America to England, determined to dig up the grave of Shakespeare. She wasn’t hoping to find just the bard’s bones, but secret documents proving the man was a fake.

She lost her nerve, though, and never dug up a corpse. Even though she wasn’t able to prove her hypothesis, she was still the first to throw out the revolutionary idea that Shakespeare was actually a group of writers all helping pen the plays with Sir Francis Bacon as the lead writer.

Everyone hated it. At least, at first. Unfortunately for Delia, no one really took her seriously until after her death. She died in an insane asylum, two years after the publication, devastated.

devastated:

She also convinced herself along the way she must have been related to the great thinker, Sir Francis Bacon. She wasn’t.

Shakespeare’s ghost sighed in relief and rolled back over in his grave, undisturbed. But he wasn’t out of the woods yet.

Whodunnit?

It’s possible the esteemed author of such masterfully witty phrases as, “More of your conversation would infect my brain,” couldn’t write a sentence, let alone some of the greatest insults ever thrown at another person. But someone had to come up with lines such as, “Methink’st thou art a general offense and every man should beat thee.” So who did?

At last count, seventy-seven candidates have been in the running for the real William Shakespeare.

Of course, in order to dethrone the king of playwrights there had to be more evidence than Shakespeare’s simple lack of education. So the manhunt began.

Since doubters convinced themselves it had to be a court insider, everyone started looking for a nobleman. Sir Francis Bacon was the first, but he wasn’t the last. It got pretty easy to see clues in every mundane detail the deeper into conspiracy theories people sank. They hunted through Shakespeare’s plays to find clues and cryptograms regarding the true author, and they came up with wild answer after wild answer.

By looking hard enough, some started to think the playwright was none other than Queen Elizabeth, herself. Maybe she used William Shakespeare as her face to the world, since she was a girl and girls weren’t allowed to publish plays. Especially if that girl was queen and the plays were for the common masses. It might sound crazy, but people like crazy. (For the record, it wasn’t the queen.)

More modern literary analysis (i.e., not simply digging up graves) studies patterns in the writings using computer programs. This way, scholars can pretend they’re CSI detectives. They look at things like repeated words and phrases in all Elizabethan works. Even the classical blunders in Shakespeare are used to prove that the man from Stratford didn’t need a college education to write the plays. In fact, it would make more sense if he didn’t have any university learning.

These experts also trace the development of the writing over the years as Shakespeare matured. Then, they compare it to the known writings from other candidates to compare writing tics, peculiar words, spelling patterns, and the handwriting itself. All of these linguistic (language) patterns act like fingerprints to help ID authors instead of bad guys.

These methods have allowed scholars to discover a number of things about Shakespeare’s plays. First, if some of the handwritten manuscripts are really Shakespeare’s, he had worse penmanship than a preschooler. But you already knew that from his signatures.

Second, at least five of the plays were co-written, but it may be many more. Like most playwrights working for theater houses of the time, Shakespeare didn’t write alone. He collaborated with actors and writers, hoping to beat out the other theater houses for best attendance. To do that, he needed lots of plays oozing with dirty jokes and potty humor. Even a genius can only come up with so many fart jokes and stinging insults, so he had lots of help from fellow bawdy players.

Third, almost all of Shakespeare’s plays came from an earlier source. Elizabethan writers wouldn’t call it plagiarizing back then and adapting older stories for a modern audience is nothing new. (Ahem, Homer.) Everyone did it.

Shakespeare’s most famous play—The Most Excellent and Lamentable Tragedie of Romeo and Juliet—was borrowed. Fellow Englishman, Arthur Brooke, published a poem titled The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Juliet in 1562.

Brooke’s version wasn’t even the first. There’s an older Italian version of the star-crossed lovers’ story. Clearly, this tale about doomed teenage love had been kicking around Europe for quite some time before Shakespeare added his own flair.

Besides tweaking some names, and adding enough suspense to make Hollywood sob with joy, Shakespeare also transformed the moral aspect of the Romeo and Juliet story. Arthur Brooke’s characters were “a couple of unfortunate lovers thralling themselves to unhonest desire, neglecting authority and advice of parents and friends.” In other words, they wind up dying because they’re young and stupid.

A little help here?

But for romantic Shakespeare, that ending simply wouldn’t do. He made Romeo and Juliet a “pair of star-crossed lovers” whose tragic deaths end their parents’ constant fighting.

That’s one for true love, but the real winner is the Grim Reaper. He gets his victims in both versions.

True love at first sight: 1. Grim Reaper: 2.

(It does say tragedy in both titles, after all.)

So forget what you think about Shakespeare making up all those devastatingly romantic tragedies. He wasn’t the first, and he won’t be the last.

Fame Game

Who doesn’t love a good scandal? A man who, for hundreds of years, parades around as the best playwright and poet in the Western world pretty much tops the list of good scandals. If it’s true—and William Shakespeare really was just a small town boy who became an actor and nothing more—then William Shakespeare the writer was more phony than baloney. He could’ve been a pen name for any number of noblemen (or noblewomen) but he wasn’t the man we learn about and revere today.

Pick Your Camp

When it comes to who produced Shakespeare’s work, the sides don’t just break down into Strafordian or Anti-Stratfordian camps. It’s way more complicated than that. Baconians are Anti-Stratfordians who believe Sir Francis Bacon wrote Shakespeare. Oxfordians believe it was Edward de Vere, the Seventeenth Earl of Oxford. Currently, Oxford is the top candidate and here’s why:

• He had classical training, a lawyer background, and the court know-how so resplendent in Shakespeare’s works.

• He was known as a writer by his contemporaries.

• He traveled all over Italy, where thirteen of Shakespeare’s plays are set.

• The plays seem to follow his life.

• Oxford’s family has links to the publication of Shakespeare’s First Folio, a collection of thirty-six plays printed after Shakespeare’s (and Oxford’s) death.

If that doesn’t convince you, then you probably don’t believe in Sasquatch, either.

On the other hand, maybe he did exist as William Shakespeare the writer, but not as the single genius slaving over quill and parchment, straining his eyes by candlelight. Maybe “Shakespeare” was a pen name for a collaborative set of writers trying to make a shilling or two off their witty wordplay.

The debate will rage on, but as Charles Dickens once said, “The life of Shakespeare is a fine mystery, and I tremble everyday lest something should come out.” In other words, maybe the mystery is the best part of William Shakespeare.

Or perhaps the mystery of the famous bard is really just a warning: Don’t get too famous, or in another five hundred years, everyone might wonder if you ever existed.