Chapter

8

Pope Joan

Not to be Confused with Pope John I-XXIII

“Occupation”: Pope

“Lived”: England, Germany, Greece, Italy

A Letter Off

One day in the Middle Ages—855 CE to be exact—Pope John was riding a horse to St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Whenever the pope went anywhere he was surrounded by lots of people who wanted to be close to his Holiness. That was usually a good thing. It meant he was loved and adored. But on this occasion, it was bad news for Pope John. Very bad news. That’s because the Holy Father was actually a holy mother—the world just didn’t know it yet. Yes, Pope John was really Pope Joan.

As soon as everyone realized the pope was a woman AND giving birth in broad daylight, they got so angry at being duped that they started throwing stones at her. Literal ones and probably pretty big ones, too, because they ended up stoning Pope Joan and the baby to death. Not a pretty sight.

stoning:

There’s a nicer version of the story that claims Pope Joan was whisked away to a nunnery and allowed to raise her son there, but most accounts prefer the gruesome ending.

You probably have a lot of questions right now. The biggest one is: How the heck did a woman ever get elected pope in the first place? Women aren’t allowed to be priests, let alone cardinals, bishops, and popes! Or, perhaps you’re wondering if the whole story was a fake, and if so, who started it?

You’re not alone. People have been talking about Pope Joan for centuries. They’ve debated her existence, tried to silence her story, and used her as a poster child of a corrupt church. What’s weird is nobody talked about a Pope Joan until hundreds of years after her unfortunate demise. It was as if nobody found the story strange. Then they couldn’t stop talking about her.

The Evidence

The first mention of Pope Joan comes from a Catholic source. According to Jean de Mailly, a Dominican friar writing around 1250, a really smart woman decided an endless life of mind-numbing chores and back-breaking drudgery in a mud hut didn’t suit her. She was too clever to spend all day hefting sacks of cow poo over her back and fertilizing gardens.

So she did something about it. She cut her hair, dressed as a monk, and went to study in Italy. Since she was so smart, she worked her way up the papal ladder until she was unanimously voted in as pope around 1100. De Mailly’s account ends with Pope Joan getting stoned to death. He also ended it with a caution, saying he doubts the truth of the legend and that someone should really look into it.

This story didn’t make any tsunami-like waves in the Catholic Church—or even a watery ripple—probably because, in 1250, the only people reading de Mailly’s chronicle were other monks. But then, years later, another Dominican writer found the legend of Pope Joan. Martinus Polonus must have liked the sound of a popess because he took the story and ran with it, giving the woman a name, fleshing out her backstory, and even adding a motive to the crime—ooey, gooey love. (You know what they say. Give a medieval monk an inch and he takes a mile.) His version became the version of Pope Joan and everyone excitedly copied it.

copied:

This was back when if you wanted to publish a story, you had to write it out by hand under dim candlelight—each and every copy.

According to Polonus, the woman’s name was Johannes, but she went by John of Mainz. She disguised herself as a monk in order to go traveling and studying in Athens with a boy, but ended up delighting all of her teachers with her exceptional brain once there. Then she went to Rome. It didn’t take long for everyone to realize “John” should become the next pope. Polonus thought she was elected around 853, so the dates are different from de Mailly’s account, but the ending is still the same—Pope Joan gives birth and dies under an onslaught of rocks.

Once again, no tsunamis of protest spewed from Polonus’s account. Why was this? Shouldn’t a cross-dressing, lying, female pope be what you’d call “a problem” for the Church?

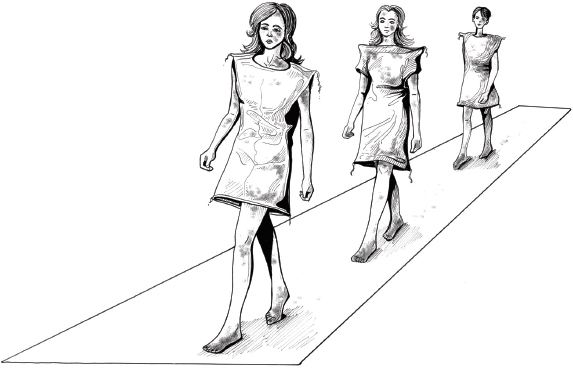

Not really. At least, not at first. The fact that a woman dressed as a man and got away with it wasn’t really an issue. That kind of thing happened more often than you’d think. It was easier to do at a time when people didn’t bathe as much and wore baggy linens for clothing. Monks’ outfits were even better for hiding womanly parts. Their potato sack couture covered everything, even delicate little wrists.

Actually, it might not be too difficult to keep the jig going—until death, at least. There are around twenty different male saints who ended up being women. No one knew until they died and started washing the body for burial. (Except for the most famous cross-dressing saint of all time—Saint Joan of Arc. She didn’t pretend to be a man. She just dressed like one, since riding a horse is easier in pants than a dress.) All twenty of them still got to be saints. So this sort of thing happened, and everyone went on with their lives. Throughout the fifteenth century, no one doubted the story of Pope Joan, and no one much cared.

Someone call the fashion police!

A few people used the story of the female pope to attack the current pope, but even then, no Catholics questioned her existence.

If a Girl Could Do It . . .

Even before the Protestant Revolution, people used the story of Pope Joan to criticize the Catholic Church. Here are two of the more famous critics:

Giovanni Boccaccio: an Italian humanist. Yes, Boccaccio was certainly human, but that’s not what a humanist is. Instead of focusing on religious stuff, humanists focused on the humanities: logic, grammar, history, and so on. Boccaccio is best known for the Decameron, a series of poems and tales, but he also wrote about Pope Joan. He put her among his “most famous women in history” book, De Claris Mulieribus (published in 1374). For Boccaccio, it wasn’t a question of whether Pope Joan actually existed. She clearly did. It was more of a question of the Church allowing bad leaders to take charge all the time. To Boccaccio, they needed some serious help. As for her death, he doesn’t mention it. He says a bunch of cardinals (not birds, but priests) put her behind bars for the rest of her life so she could think about what she did—that wicked woman.

John Hus: a Bohemian reformer. Hus really didn’t like the pope, but there weren’t a lot of options for changing religions in medieval Europe. So, instead, he wrote a bunch of angry letters stating things like the Church was perfectly capable of functioning without a pope. Look at all the times when a false pope was on the throne, like that woman, Joan. This didn’t exactly make him popular with the pope, who had John burned at the stake in 1415.

She’s even mentioned in a medieval guidebook from 1375 so interested travelers could visit the site of her stoning near the Colosseum, and probably search for bloodstained souvenirs. After the sixteenth century, Catholics everywhere decided the story was fake and denied it like mad. So, what gives?

One word: Protestants.

Collateral Damage

In 1517, Martin Luther, a soon-to-be fugitive, tacked to a church door ninety-five reasons why he felt the Catholic Church’s rules stunk and ways to make them stink a little less. Long story short, the Church didn’t appreciate his suggestions and excommunicated him.

excommunicated:

They kicked him out for good.

Luther didn’t go down easy. Or alone. He brought lots of unhappy Catholics with him, and this split led to a new sect of Christianity: Protestantism. It wasn’t an easy or happy split. In fact, it was even more bitter than when Yoko Ono split up the Beatles and it led to hundreds of years of name calling and bloody wars.

After the Church split into Catholics and Protestants, Pope Joan wasn’t the black sheep of the family anymore, or even just some embarrassing rumor. She became a sheep in both sides’ cross-hairs.

Protestants were positively giddy to come across the old story of a female pope. To them, it showed why the papacy had to go—it had become a sad joke. In the eyes of the Protestants, Pope Joan proved that Catholics were so corrupt that they had thrown all their traditions down the toilet, which in sixteenth-century Europe was usually a hole in the ground (cesspit) or a box with a lid for fancy folks.

To really drive the point home, Protestants turned Pope Joan into a sorceress, a necromancer, a demon, and a pawn of the Devil. There was no way a woman could be that smart! She must have signed her soul to the Devil in exchange for a brain. And the Catholics were too corrupt to see it happening or to stop it.

To be fair, this happened with male popes who were brighter than the average candle, too. Pope Sylvester II (pope from 999 to 1003) was also accused of signing away his soul to the devil, so it didn’t always pay to be smarter than everyone else in medieval Europe. Suddenly you got accused of inking blockbuster deals with the devil.

With all this hostility, there was only one thing the Catholic Church could do—play Peter and thrice deny. In 1562, an Augustinian friar set out to disprove all the Pope Joan stories. Soon, the whole Church backtracked, saying this story about a popess was nothing more than Protestant drivel. Then they tried to wipe out all traces of her. This included getting rid of any statues of her, like the one in the Siena Cathedral in Italy. Pope Clement VIII had it re-carved into a different pope in 1600—and he made sure it was a male one.

Aristotle Was Here!

Graffiti is very common today, but it isn’t a modern invention. People love to scribble their mark on the world. There’s graffiti from ancient times making fun of Julius Caesar, and there’s graffiti from medieval times in manuscripts. One manuscript has graffiti in the margins that states: “The Pope was a woman.” Now, clearly this sounds like something a sassy Protestant would scribble in a Catholic book, but when scientists tested the ink, they found it was older than Protestantism. Only a Catholic could have done it. So much for denial!

Protestants didn’t let the matter go that quietly, however. During the Protestant Reformation, Pope Joan had hundreds of pamphlets written about her. It was an all-out smear campaign. Just because there’s a lot of stuff written about her, though, doesn’t mean she was real. It means people liked the idea of her.

Protestant Reformation:

It started with Martin Luther in 1517 and ended in 1648 after a long, bloody war called The Thirty Years’ War—no points for imagination. By the time the war was over, people had forgotten what they were fighting about.

The only thing the Catholics could do was feign ignorance—who, us? And this leads to the big question: Why did they create a story about a woman pope in the first place?

Scared of a Girl

Back in the thirteenth century, when Jean de Mailly and Martinus Polonus lived, women started to want new things for themselves. Not shoes or purses, but positions of power in the Church. They could be just as religious as men, they insisted, so why couldn’t they be leaders, too? Why couldn’t they hear confessions and touch religious vessels? Women wanted to be priests and they wanted a chance at an education. It was a mini-renaissance in the thirteenth century, and it scared the mitre caps right off the men in charge.

This was also the time when a lot of cross-dressing happened. Women dressed as men so they could learn. The male priests didn’t like this, but there was one thing they didn’t like even more.

Large numbers of women were forming their own religious communities and they weren’t consulting any men first. These independent women were called beguines, and they didn’t need a man telling them what to do.

How about a sparkly pair of shoes instead?

To priests, this was even worse than the large number of women trying to get into the man-approved convents! Eventually, in 1312, the Council of Vienna outlawed the beguines and married them all off instead.

This political background explains one of the most popular theories about the source of the Pope Joan story. At a time when women were gaining more religious authority, some think that it was invented as a cautionary tale to help keep women in check. Look what happens when women try to be priests—they give birth, which is kind of a deal breaker. According to priests, you can’t be thinking about God if you’re having a baby.

beguines:

Religious women who weren’t nuns. They formed a girls only clubhouse and made up all their own rules about worshiping and religion, and generally annoyed/scared priests.

Another theory involves politics of a different kind. Some think the story of Pope Joan started because the Dominican authors wanted the popes at the time to stop acting like spoiled brats and start behaving themselves. (Obviously, those popes took power away from the Dominican priests ASAP.)

By pointing out that a woman was allowed to hold the highest position in the Catholic Church, the priest showed that mistakes happen even at the highest level. If a woman could become pope, so could a wicked man. (Hint, hint, he seemed to be saying. There might be a wicked man on the papal throne right now.)

Even if that wasn’t the source of the Pope Joan story, it was used that way. In 1332, a Franciscan friar, William of Ockham, went to a lot of trouble connecting the dots between Pope Joan and the current corrupt pope. The point of his exercise: if God allowed a false pope to be in charge once, he could do it again.

In either case, both possibilities highlight what men thought about women at the time, and it wasn’t very nice.

Knocking on Wood

Whether or not Pope Joan’s story was true (doubtful), superstitions surrounding it stuck with people. Some Italian families liked the story of a popess so much that they had their tarot card decks include Pope Joan as the trump card.

Trump that!

Popes in the fifteenth century always took a detour around the road where Pope Joan supposedly gave birth, although it wasn’t certain if she existed and therefore had a child. Even the street was named after her, Vicus Papissa. One pope, Innocent VIII, got in trouble for refusing to avoid the intersection. Popes don’t avoid it now, but that may be because the street was widened in the seventeenth century and their processions can actually fit down it today.

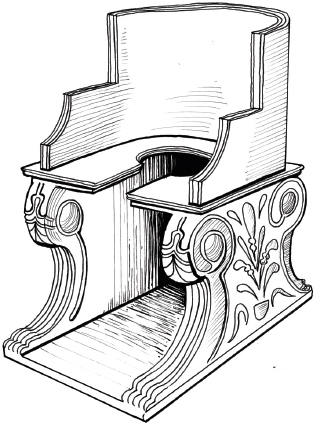

Another tradition stated that the prospective pope had to sit on a throne with a hole in it before becoming pope. A lowly deacon felt around, made sure the new guy had the goods, and declared to the world that the pope was indeed a man (just in case a cross-dressing woman ever tried that stunt again). This doesn’t happen today, if it even happened in the past.

Pope Joan was never meant to be fawned over and admired. She was too scary for that. Instead of illustrating that women can successfully hold power, the story of Pope Joan showed what happens when weak men were in charge—they let women grab their power. It also “proved” that intelligent women were dangerous, since they were probably in league with the Devil to get that smart in the first place. Thus, it became common practice to keep women locked away in the nunneries and the kitchens so they couldn’t test out their smarts.

Yet to this day, modern women look to Pope Joan to prove how far a smart woman can go—all the way to the top. Martinus Polonus said in his narrative that Joan was a successful pope until she gave birth. Some Protestant writers claimed that she was a better pope than all those really bad male ones—like the ones who had hordes of illegitimate kids or lived like kings instead of priests.

Just checking . . .

Pope Joan continues to be a twenty-first-century icon symbolizing what women could accomplish in the Church in the Middle Ages and beyond. Pope Joan really can’t be much more than that today since her story might be just that—a story.