Chapter

11

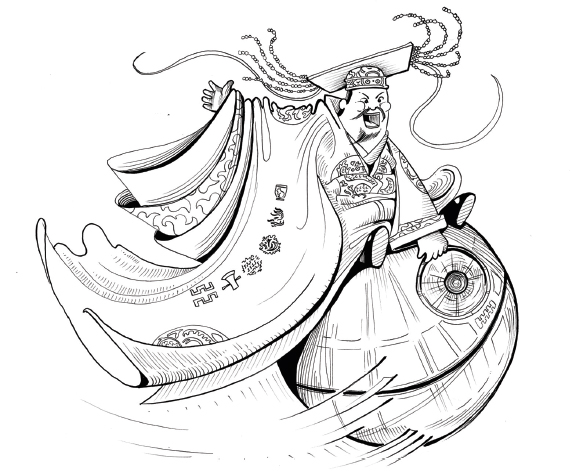

Huangdi

The Yellow Emperor Strikes Back

Lived: Twenty-seventh century BCE, China

Occupation: Ancestor of Chinese Civilization

Not Exactly Building the Death Star

What emperor chased a rebel, didn’t mind a little violence, and called up a magical force to help control an army? If you said the galactic Emperor from Star Wars, you’d be close, but you’d be wrong.

Huangdi (pronounced Hwahng-dee), the Yellow Emperor of mythical China, may not have chased Luke Skywalker around the galaxy, but his influence echoed across time and space, just like the evil Emperor Palpatine. They even had similar tactics, like using organized violence to maintain discipline in their empires. Okay, sure, instead of building the Death Star, Huangdi rode into battle on horseback and unified the rebels. And instead of using the Force, the Yellow Emperor called upon the drought goddess, Ba, for help. But besides that, they’re practically the same.

Including the fact that neither of them existed, those phonies.

Usually, a legend grows around a real person whose memory blows up to epic proportions. Not so with the Yellow Emperor. In fact, it’s kind of the opposite. Huangdi started out as the sky god, Shangdi (pronounced Shang-dee), which seems like a better gig. Eventually, he morphed into a man, who then became a god again. Confused? Don’t worry, so is everybody else.

My other ride is a yellow dragon.

Supposedly, the Yellow Emperor ruled around the twenty-seventh century BCE, and while it’s hard enough to verify the lives of people that far back in history, it becomes oh-so-complicated when the first records of his name come 2,300 years later.

From God to Man and Back Again

One of the early Chinese gods, Shangdi, figured into a lot of myths over the course of Chinese civilization. Even the earliest dynasties knew about Shangdi. His name looks a lot like Huangdi’s in Chinese. Some think that those living in the Warring States Period remembered the old stories, reworked them, and created a legendary emperor who represented their times, making everybody scratch their heads.

Huangdi is from the probably mythical dynasty that includes the likes of fellow sage emperors Yao and Yu the Engineer. While Huangdi didn’t get as cool a nickname as Yu, he became the supreme ruler of the five sages from this legendary period (a.k.a., the good ol’ days).

Even if the job didn’t technically exist, the Yellow Emperor definitely got better publicity than the Galactic Emperor. He’s sailed through history as the ancestor of everything Chinese, all thanks to some guys during a time called the Warring States Period, which, as you might imagine, waged a lot of wars.

This is that story.

Gentlemen Don’t Start Fights . . .

The Yellow Emperor’s legend starts with your typical half-dragon, half-human baby story. He rose to power in the regular fashion—that is, by brute force. He lived on the plains of Guanzhong (pronounced Guan-sha-ow), but instead of hunting and foraging like everyone else, he preferred kicking butt and taking names. Seriously. After he defeated one tribe and brought them into his fold, he’d take that tribe’s name into his own.

First on his list was the Yan Emperor, head of a plains tribe. Some of the other tribe leaders didn’t like the way Yan was looking at them; it kind of seemed like he wanted them. So they asked Huangdi for help. Huangdi saw rampant disorder all over and knew there was only one thing he could do. Huangdi decided it was time to take control of Yan’s men for Yan’s own good. You snooze, you lose, Yan.

As you can imagine, Yan didn’t quite agree with this assessment so the only thing left to do was to duke it out in the first big battle of Chinese history: the Battle of Banquan. (Note: extremely legendary. Possibly never happened. Evidence scarce.)

Luckily for Huangdi, he just so happened to have tamed six wild beasts before the battle, including bears and tigers. They really helped turn the tide in Huangdi’s favor. The Yan Emperor realized he was no match for these beasts and formed an alliance. Huangdi named the new, larger tribe Yan Huang, and they planned to have a swell time ruling the plains together.

Of course, people were jealous of Huangdi’s new tribe and all his power, even though he was only trying to keep the peace through war. Nothing wrong with that. However, Chi You (pronounced Chih-Yo) decided he was the rebel to challenge Huangdi. Some say he was a jealous minister to Huangdi; others say that he was a random guy on the plains who would have really enjoyed WWE or UFC (if such things had been around). If Chi You had been able to take his aggression out in a cage match, maybe he wouldn’t have tried to take it out on Huangdi.

Either way, Chi You led over seventy tribes against Huangdi in an all-or-nothing smackdown. It didn’t go Huangdi’s way this time. He may have tamed multiple beasts, but Chi You’s soldiers were made of bronze, which sounds suspiciously like men wearing suits of armor. Except bronze smelting probably hadn’t been discovered yet, and the oldest bronze armor ever discovered dates from 1,500 years after this battle.

After Huangdi’s humiliating defeat, he went up into the mountains to have a long think about what went wrong against the vicious Chi You. Like a three-year think.

While there, a goddess came to help him as they tend to do for heroes. She gave him sacred texts and tools that would turn the battle from a merely physical confrontation into a mental art. No more running around like mad, screaming and waving a sword. Huangdi would have to have style on the battlefield.

In serious need of a cage match.

The next time Chi You and Huangdi met was at The Battle of Zhoulu, which would decide the fate of all the tribes living on the plains. The fight didn’t start the way Huangdi hoped. For one, Chi You started burping out fog that made it hard to see, but Huangdi had a solution for that. He invented the South-Pointing Chariot, which is a chariot that points south, to help his soldiers out of the fog.

Then, Chi You made it rain. Instead of cats and dogs, it was more like demons and chaos and more rain. Huangdi called on his goddess friend, Ba, to conjure up a drought and dry out the land. It’s possible that Ba was also his daughter, which would make it easier to ask for help. Having solved the rain and fog issue, Huangdi captured Chi You. Since Huangdi didn’t want any demon blood on his hands, a dragon came down and slew the rebel for him.

All the tribes around the Yellow River were now his. Next on his list: world domination! Just kidding. Being the ancestor of all Han Chinese was good enough for Huangdi.

But They Finish Them

After all that war, the plains got a lot of peace, which led to a golden age. Before Huangdi, people wandered from tree to tree searching for safe places to sleep each night. As cool as a tree house sounds, it wasn’t as nice as a fluffy bed. He also showed them how to cook their food and tame animals, like he did for the battle. In other words, he created civilization, because without these things, humans were one small step away from being beasts themselves.

Huangdi didn’t stop there. Besides the South-Pointing Chariot, which was both a compass and a chariot, he created other vehicles like boats and carts, bowls for all that newly cooked food, a calendar, and cuju, a form of Chinese soccer. Huangdi wasn’t selfish. He let his loyal ministers get in on the action, too. His historian invented the Chinese character system in order to better record Huangdi’s awesomeness. His minister invented bamboo flutes and found the five tones and twelve scales needed to bring beautiful music to Huangdi’s ears.

Even Huangdi’s wives seemed to have a special touch. One invented chopsticks to go along with the bowls, and another came up with an idea for a comb. As cool as chopsticks and combs are, Huangdi’s most famous wife, Lei Zu, discovered something even better—a worm that burped up pure perfection! Okay, not perfection, but close enough. She discovered the secret to raising silkworms after a cocoon dropped in her afternoon cup of tea. And the worms weren’t exactly burping up silk, but spitting it up to make their cocoons. The heat of the tea unwound the silk of the cocoon, which is actually silkworm spit.

Huangdi’s brilliance in a nutshell.

tea:

Although tea drinking wasn’t a national custom until the eighth century CE during the Tang dynasty. Details!

After Lei Zu figured out the threads were soft as well as strong, she invented the silk loom and taught people how to make luxurious clothes fit for an empress, which happened to be her. Legend says she was the ugliest woman around, but Huangdi liked her best since she was smart.

In reality, most of these things weren’t invented until centuries later during (and even after) China’s Bronze Age, but that didn’t stop people from tacking their inventions onto the legend of the most famous sage, the Yellow Emperor.

Classics of Internal Medicine

This first book of medicine in Chinese history had a lot of radical ideas rolling around its pages. It included pearls of wisdom like demons not causing illness. At a time when Western doctors still believed a woman became sick when her womb went wandering, this was oddly on track.

Even though Classics of Internal Medicine was written during the Warring States Period (two thousand years after Huangdi “lived”), the text is supposedly a conversation between Huangdi and his ministers in the form of questions and answers. To them, old age, lack of exercise, bad diets, and rowdy emotions caused sickness. Sure, the diagnosis could be off the wall sometimes and often depended on things like the time of day, the season, and the gender of the patient, but the treatments were better than the hang-upside-down-for-a-day solutions the Greeks had in rotation around the same time. And the holistic knowledge imparted in the text is still used today in Eastern (and some Western) treatments, like acupuncture, circadian rhythms, and ying and yang.

Despite Huangdi being the personification of perfection, he couldn’t stay on earth ruling forever. A yellow dragon eventually came calling and whisked him away to heaven, making Huangdi immortal. No word on whether the dragon was related to him.

For the next two thousand years, give or take a few centuries, things got pretty quiet for Huangdi.

You Can’t Stop Violence without More Violence

The Warring States Period didn’t get its name by handing out flowers and candy every day. Instead, nobles handed out dagger-axes and swords and generally made life hard for regular people. If they had a motto it would have been: only violence stops violence.

It was a chaotic time and the Warring States elite looked to old stories, legends, and myths to help them stake a claim to someone else’s land. They justified a whole bunch of stuff based on these stories, as well as the new ones they made up about the sage emperors.

Nothing says, “Welcome to the neighborhood” like a dagger-axe.

A Pit Stop on the Way to Immortality

On his dragon-mounted trip to immortality, Huangdi decided to take a brief detour. In order to comfort his people, he dismounted in Yan’an City to say goodbye and to plant a cypress tree. This was a bad idea. His people didn’t want to be comforted. They wanted Huangdi to stay. As he tried to slip away on his dragon, they tore his clothes off and Huangdi had to flee butt naked.

Today, Huangdi’s mausoleum (a really big tomb) is located on the site, and yearly offerings have been made to his honor on and off since the Warring States Period. The cypress tree survives as well as an imprint of Huangdi’s feet.

Huangdi had a light step.

Since Huangdi pretty much lived the dream life— one guy conquering all the other guys—it’s no surprise that the Warring States nobles pegged him as their hero. His name appears for the first time in writing during this period (despite the fact that Huangdi invented writing). A bronze vessel mentions his name and the convenient fact that the Yellow Emperor had just used Tian to overthrow his enemies. People liked the sound of that.

He’s mentioned in passing in other texts, too, mostly associated with the idea of ruling by force. One text really liked the idea of killing as punishment and claimed the modern state came from Huangdi. The strong should overcome the weak and tell them what to do, just like Huangdi, otherwise everyone would go back to being beasts again. After all, Huangdi was made immortal, so it must be okay. Right?

A Period of War and Thoughtfulness?

Interestingly, the chaotic Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period are also the time of the Hundred Schools of Thought. Since there wasn’t one guy running around with a tiara on his head making up all the rules, lots of people had lots of ideas about the best way to live and govern. In addition to the ideas attributed to Huangdi, this time period boasts such legends as Confucius and Sun Tzu, author of The Art of War. Legalism and Daoism were also created during this time period, and Huangdi is connected to both.

In the end, all of these stories about Huangdi tell us one thing, and it wasn’t a biography of his fabulous life. They show us what the Warring States elite thought and honored above all else. War, duh.

After all those years of fighting, the last man standing was Qin Shi Huangdi (pronounced Chin Shee Hwahng-dee), the first emperor of the first dynasty, the Qin (say: Chin) Dynasty (221–206 BCE). Of course it’s no coincidence that he had a similar name to the Yellow Emperor. Qin Shi meant to do that. It gave him more power and prestige as a ruler. It must have worked, too, since Qin Shi began the tradition of Chinese emperors that didn’t end until 1911. He also passed on the tradition of adding “Huangdi” to each new emperor’s name.

Qin Shi, like his namesake, enjoyed the idea of ruling by force. Things didn’t exactly pan out for Joe Schmos during this time. They got conned into things like building the beginnings of the Great Wall. This really did suck, with 300,000 people dying to build those original foundations. But he also unified China after the Warring States Period, standardized writing and weights, and started a national road system.

Great Wall:

Eventually, the Great Wall got its other, less flattering, nickname: the longest cemetery on earth. It’s estimated a million people died during construction. But that’s just an estimate.

Qin Shi liked one more thing about his man, Huangdi. He really liked the way Huangdi never died.

Don’t Count Your Dragon Eggs Till They Hatch

Jumping on the back of a dragon and flying to heaven to become immortal sounded like the perfect ending to Qin Shi’s own story. At least, Qin Shi was sold. This immortality thing really suited an emperor. But Qin Shi wasn’t one to sit around and just dream, so he sent out searchers to find the secret to immortality ASAP.

He didn’t put all his dragon eggs in one basket. Qin Shi prepped for the worst by having an entire force of terracotta warriors assembled over the course of thirty-seven years specially gift wrapped for his own tomb. The clay warriors’ mission was to protect him and to help him rule over another empire; one in the afterlife.

Qin Shi’s terracotta soldier—probably to protect the Emperor in the next life from all the people who died building his Great Wall.

To make them more realistic, every warrior was unique. There are over eight thousand warriors in Qin Shi’s tomb, not including chariots, horses, acrobats, musicians, and officials. All for Qin Shi’s pleasure. He was definitely ready, just in case his people never found the secret to immortality. And according to our records, they didn’t.

Even though he finally realized he wouldn’t find personal immortality in this world, Qin Shi thought his dynasty would last forever. It hung on for three more years after he died, officially the shortest dynasty in Chinese history. According to the next rulers, the Hans, Qin Shi was a brutal, book-burning ruler who lost the Mandate of Heaven (see chapter 1), and they weren’t exactly wrong.

While Qin Shi may have begun the tradition of Chinese emperors, it was the Hans that decided just about everything else until 1911.

everything else:

Including the Confucian craze, the spread of Buddhism, the Silk Road, and inventions like paper, porcelain, and a seismograph for detecting earthquakes. The Han wrote the first history book of China and started China’s love of jade for its mystical properties. They were regarded as the most powerful dynasty in Chinese history, and other dynasties liked to reminisce and look to them for inspiration on how to unite an empire. The ethnic Chinese still refer to themselves as the Han.

Luckily for Huangdi, the Han emperor, Wudi (pronounced Woo-dee), installed Confucian principles as the main guidelines for life. He included rulers acting like the sage emperors in order to get their own shot at immortality—in other words, acting like Huangdi. Unluckily for everyone else, Wudi ended up not being so different from Qin Shi after all. By the last few decades of his fifty-four-year reign, only one of his seven chancellors died a natural death.

Besides getting his kicks off of chopping up everyone from commoners to family members, Wudi also enjoyed the idea of immortality of the Huangdi variety.

Like Qin Shi, Wudi could totally see himself flying around on a dragon of his very own all the way up to heaven with all his ladies, feeling the wind in his hair and eating dewdrops. But the ladies weren’t necessary. He (supposedly) said, “If I could become like the Yellow Emperor, I would leave my wife and children behind without hesitation.” Considering he went through women pretty quickly, this isn’t hard to imagine.

A naked man ran by here.

To keep all the good mojo flowing Huangdi’s way, and to give himself a great chance at immortality, Wudi and the rest of the Han continued to make sacrifices to the Yellow Emperor and built another shrine at the mausoleum at Yan’an. Today, the mausoleum is a symbol of the Chinese nation and remains important in the current politics of the country, even getting special festivities every April.

How to Survive the Centuries

As you may have noticed, the twentieth century is when everything changed for China. Emperors were no longer around, and the country went bananas. Again.

In 1911, the Qing (pronounced Ching) emperors were overthrown and the Republic of China was born (but you can call it China for short).

The buzzword became Zhonghua Minzu.

Zhonghua Minzu:

A nickname for one big Chinese family.

To them, Zhonghua Minzu consisted of the Han and four other ethnic groups, which made up one big, happy family. It was like the Brady Bunch on a dragon-sized scale, but they called it the Five Races Under One Union. It’s probably easy to guess who the father was. Huangdi was still around, and now he wasn’t just the father of the Han, but of all five groups. Times looked good for Huangdi.

That is, until two more revolutions arose, including the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s. The man in charge, Mao Zedong, didn’t appreciate tradition or all those ancestors. Too many cobwebs. Anything that was considered old or ancient was smashed. This included everything from old artifacts to old culture to old people.

As the ancestor of ancestors, Huangdi pretty much epitomized old stuff, so for a decade (1966–1976) he slunk around in hiding. But Huangdi had already survived thousands of years. He could wait a mere ten more to steal the spotlight again.

Five Races Under One Union

By the 1980s, Mao was dead and Huangdi was back, and he had an even bigger role. Now Huangdi wasn’t just the ancestor of the five ethnic groups, but of fifty-six.

That’s a lot of kids for Huangdi to support.

It hasn’t always been one big happy family, though. The claim that all fifty-six groups descended from Huangdi has been used to rationalize China’s expansion in the region. Huangdi is probably used to all the politics, but instead of justifying invasions in the Warring States Period, he’s justifying invasions in the modern period. Which is pretty convenient for Huangdi.

More Political Than Human

Whether he was only an oral tradition, a god, or just an invention of sly storytelling elitists, in the end, Huangdi was never an actual man. Almost five thousand years later this legend is still being used in political maneuvers in China.

Just remember, stories of the Yellow Emperor were first recorded over two thousand years after he supposedly took to the sky on his dragon. If this story doesn’t smell as questionable as rotting fish hanging out in a barrel under direct sunlight for a week, then your nose must be broken.

In the end, it’s important to remember that stories reflect the times in which they were written—not the actual time they describe. Including the new ones. End of story.