She stood out vivid and present in the temperature-controlled half-light of her glass coffin, upright and at full human stature, her cloak hung to give the impression of a human figure underneath. She radiated epiphany. She filled the room with a smell like the seal-fur blankets Naaja’s mother gave us and an undertone of perhaps honey. It was strangely familiar and pleasant, not at all sickly. Her staff with the two-pronged antlers, still velvety with fur, sashed to it. On little fronds she had tiny bird skulls and shells. If she weren’t so very still they would click together like a cartoon skeleton falling to pieces. Clack-clack-clack-clack-clack.

In the park centre where I waited for the bus, there were displays on the natural and cultural history of the park. I floated around the room; there was movement from nothing but me. Time had stopped, looking exactly about to happen. There were irides-cent wings clamped open, feigning flight, above italicised names I could not get my tongue around. There were eyes, but we had taken the real ones out to put glass ones in and they stared from inside mounted skins, on placarded walls, from under glass domes, contorted majestically on rocks, on wooden plates, in awkward glory. There were tiny mottled eggs in counterfeit nests that looked as though they were about to burst out into life. And there were Dall sheep horns, a grizzly’s paw pad, skulls which though dry had all once held tiny brains, capillaries and veins.

There were artefacts of the original human inhabitants too: Athabaskan shawls, pipes and pottery. A model of a traditional toboggan and a crusty, worn dog harness. Grainy photographs of vacant-looking Eskimo men and women stood limpidly side by side with priests in robes. The plaque said missionaries won their trust with magical gifts of tobacco and medicine.

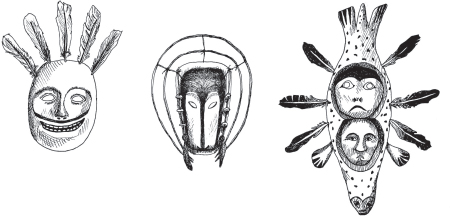

Prior to the arrival of Christian missionaries to the New World, indigenous religion was animistic, comprised of a worldview where humans are part of an on-going spiritual interchange between all manifestations of organic matter, often including the inanimate matter of the elements. A shaman was a human who was a seer into the spirit world.

Both men and women could be shamans, but many of the shamans were of female form as the idea of creation was sacred and bestowed to the feminine. However men could also have ‘feminine’ attributes. Gender was considered fluid, and there were thought to be at least four genders approximately: masculine men, feminine men, masculine women and feminine women. People who embodied the two opposites were known as Twospirit People.

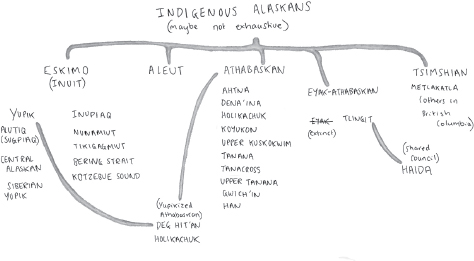

In the rest of the world Eskimo is a pejorative term and Inuit is preferred instead, but in Alaska the Eskimos prefer to be called Eskimos. There was a poster, a kind of family tree of the Alaskan indigenous peoples. Eskimo and Inuit are both the collective terms for distinct but similar cultures like the Yupik and Inupiat. Other natives of Alaska of separate cultures mostly distinguished by language are the Athabaskans, Aleuts, Eyak, Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian.

The distinctions are complicated because there are overlaps between the different cultures, and although they are distinguished by language, some of the languages are maybe not entirely separate languages. And why would the indigenous people care about absolutely distinguishing cultures if souls can transmigrate to rocks, are forever in animal-mineral-plant continuum?

On the 9 a.m. bus into the park, before disembarking, I kept my eyes porous out of the window, funnelling it all in. There were just two other people on the bus, a pair of middle-aged day hikers, and I could feel them staring at the gun leant against my seat while I jotted in my notebook.

I was waiting for the mountains to begin on the left and the treeline, which I knew to be mile 52 of the Park Road and the calculated point of my disembarkation.

The scenery flickered. It was gradual, like well-thought build-up in a feel-good coming-of-age story about a girl like me getting close to something sought. It was layer on layer. Each breaching hill might have been the one to reveal the mountains like a shroud, ghostly, slipping down. Each pre-emptive revealing was excited pressure hoarded.

Finally they were there. Mountains as turnstiles, thresholds to becomings. What do these ones mark? The ground crawled meekly to them, green and a blemished kind of red like blood soaked into moss, up and up until it rendered at rusty brown and rocky tips. Behind, another sort of brown, and behind still grey and white-capped. Each row of mountains was coloured a little differently. Layered and assembled like a collage, foreground in green. But no background of sky, instead clouds that hung and panelled forward as an overlay, disturbing the order of the layers. The mountains encroached into the sky, a challenge to its separateness.

I do not remember stepping off the bus, in a way that slightly alarms. But I do remember the light and colour: dappled impressions of moss and blood. Like Monet. Up close and in cardinal parts, tiny flowers and perfect tiny tear-shaped leaves of purple. Tiny but integral parts of a bigger whole. Micro/macro and indivisible. The timid parts actually prettier, like my own lone small journey to me. At the same time whole and partial, sublime and obscure but sentimental.

A couple of hours after disembarking from the bus and I am caught. Until that point I had been plodding along absent but receptive. Then it hits me very suddenly as I stop to drink some water from my bottle and sit on my haunches and look up at the sky, where a huge bloody eagle of some kind is wheeling about. This is it. This is everything. This is my moonwalk.

After the Apollo missions lots of the astronauts would talk about a similar sudden awareness of self. After giving all their concentration to lift-off and getting up there without exploding and feeling tense and so overridden by adrenaline that they were not even that aware of where they were and what they were doing, so that when it did hit them the feeling was potent and alarming. Others never experienced the feeling because they did not ever stop putting all their resources into the functionality of the mission. Many of the Apollo astronauts experienced their time in space not as selves but as detached scientists.

The tundra is always whistling and it is very empty. I have enough freeze-dried food as base rations to sustain me with hunted stuff for four weeks – the ecologist Aldo Leopold said that three is enough time to get to grips with real solitude and become truly immersed in wilderness. To get into the rhythms of it. Technically past two is classed as ‘settling’ rather than a camping trip and is against park regulations, but I have it from Stan that no one will notice. Stan showed me how to use a radio like the one that would be in the cabin to get in touch if I need him. He has one back in his house for when nobody is in the warden’s office.

It took me around nine hours’ marching with only a slight deviation. Stan told me, ‘If you hit the river where it leaves the forest then you are too far north,’ but I couldn’t see the river and had to just hope that this was because I was south of it. I was.

The cabin is everything I dreamed it would be. When I finally saw it from across the tundra I yelped and felt proud of my own tenacity. It is sat just left of some evergreens and looks out onto the tundra. There is an empty smokehouse outside and a tiny toilet shed, a collapsed and moss-covered pile of logs, and a broken pair of skis. Inside there is a mounted fox head, a row of gun mounts, where I have mounted Stan’s gun, some pots, a canvas cot, a fire grate, the radio on a desk with a chair and the supplies I bought. When I move about and unsettle the dust that is uniform and thick I have a sneezing fit. I fitted the radio with the batteries I bought first thing, but I turned it off this evening and intend to keep it so.

Of course, I also brought loads of books to the woods from a bookshop in town, a pile of the canonical texts on wilderness to help me decipher it. I have some Thoreau, Emerson, Hemingway, the Unabomber and a biographical book about various young male runaways. A heavy but a necessary burden. When Jack London went to the Klondike he read Origin of the Species (which explains a lot) and Paradise Lost.

Stan didn’t show me how to shoot the gun and I obviously did not ask. I have looked it over and it is pretty similar to a rifle I used to shoot with an ex-boyfriend whose family liked hunting. He used to say he was sad about hurting all the animals, and that was why he would just be the scarer that ran into the grass to get the pheasants up. The real reason was he was a terrible shot; he just didn’t want to say it to me because he was sore that I could shoot better than him. I would not shoot animals, mind, we just used to practise on targets in a field behind his house.

I am the only human being for miles around as far as I am aware. At least, that is what I was told by the bus driver, who thinks I am a day hiker too and was concerned enough for my welfare as it was that I did not correct him. He told me to look out for reindeer, caribou, foxes, pine martens, hares, wolves, wildcats and bears. Most are technically edible but I only fancy the smaller things. I have seen Bear Grylls killing and gutting many large animals and it always seems so unnecessary and superfluous. I mean, Bear Grylls obviously eats bears, that is where he gets his name from, right? He eats bears because it is essential to his identity as a born survivor. If he did not eat bears he would not have a job. I am only killing for one and I am only small. I think a hare a week will be more than enough to sustain me with the freeze-dried stuff.

Is it cheating to bring the ‘just add water’ survival packs? I had to really think about this before coming out. If I did not have them I would have to hunt for all my food. But people who do this kind of thing always bring supplies. Ernest Hemingway, writer of manly short sentences, took canned pork and beans. Inuits have supplies in the way of preserved foods. Modern Mountain Men buy sacks of pinto beans from Fairbanks. And if bringing supplies was cheating, maybe I should not really have technology like a gun or a radio. And that would not be survival technique, but a probable death-experiment. This thing, this authenticity, how close can you get to it? How pure can it be?

I also would not be able to make the video diary, which would undermine the entire point of the trip. The diary might seem a bit false, might add an inverted voyeurism so that it is really like I have company out here, but I don’t really know how to avoid this. When Bear Grylls cut open a camel to demonstrate how to sleep inside it I doubt if he actually stayed in there all night, snug in his authenticity, with his cameraman asleep in a tent pitched next to him.

How do you really front the essential facts of life authentically? Probably it is not even possible in our time of saturation. I can only try my best. Maybe writing is less inauthentic than the audience of a camera. But even then I am writing to be read, so again the ‘solitude’ is tainted by the inverse voyeurism. Go tell that to Thoreau and Heidegger and the Unabomber.

LITTLE SHORT SENTENcES

I went for a walk around yesterday to get to grips with the area in order to draw my first rough map. I had taken for granted that it would be easy to find something to eat, but after a few hours it started getting dark so I had to head back without finding anything (I did find a water source, though, a spring that is only a ten-minute walk from the hut but took me hours to find). It is difficult because I spent a lot of time singing to myself so that the bears would hear me coming and keep out of the way but that also scares away the food. When I got back I settled into the hut, arranged all my blankets on the cot, and got a little fire going in the fire grate.

I tried for about fifteen minutes, rubbing sticks together, then gave up and used the gas lighter, and cooked some instant noodles. I did feel kind of fraudulent with my lighter and my sachet of flavour, but if it is good enough for Hemingway then it is good enough for me. I sat and watched the noodles bubble, then I sat and watched them cool as I fed Stan’s map to the flames in the grate, watching it curl to cinder. With it gone a pressure released; like McCandless I am alone, it is again a wilderness to me, the places I had not seen yet still to be discovered. Like vaporising Voyager 1 out of the sky with a laser beam, zap!

Today I tried again, but I headed out first thing in the morning to give myself plenty of time, thinking immaqa. I was awake for most of the night anyway. I had not given any thought to how it would feel the first night and alone. There was too much sound to sleep, sound I could not place, the cabin being saggy with age. Mostly I stayed awake because I had a feeling like something was about to happen, or like it had happened and I had not yet put my finger on it. Like everything for a while had been hyperreal sets and stage props but now I was in real real-life, everything with a shining core. It was so bright I could not sleep for it. It was not danger and I would not say I was scared. Just very, very awake.

Tips for being not-scared at night:

– Always sleep in tight corners facing outwards, towards the door

– Fill a rubber hot-water bottle with boiling water and curl around it like it is a live, heat-giving companion

– Hum songs to trick yourself into feeling calm

– Think of the cabin as a living guardian, then its creaks and groans will comfort not unnerve you. It affords you shelter. It is your best friend

– If you hear an alarming noise, imagine it over and over again until it no longer alarms you

– If you are still alarmed, try being just as alarming. Go outside and confront everything. Yell at it all. Send any wild animals scurrying into the night. Look at it a while, to convince yourself it is still and unthreatening

I went out as soon as the sun was up enough. I did not do any of the singing this time so that I could go in stealth. First thing I came across apart from the things that ran away before I could see them was a caribou. She was standing behind a tree just ahead of me and had not noticed me, but as soon as I saw her I stopped and must have drawn in breath or something because she looked right at me. She stood there looking at me and kind of puffing cold air out and looking nervous. I thought about shooting her and just living off her for the whole four weeks so that I only had the guilt of one soul on my conscience. But then she stepped forward slowly and her little baby stepped out from behind the tree after her and I was shaking so bad I do not think I would have hit her anyway. They both trotted away and the baby tripped a bit in panic and I had to sit down for a whole minute to stop the shaking.

After I had been out for a good five hours, although I could not really say because I don’t have a way of telling the time apart from on the laptop, and the sun moves at a pace I am still not accustomed to, I started feeling tired, hungry and irritable and began to carry the gun less half-heartedly so that I could just go ahead and shoot the next thing I saw. I wound myself up being all stealthy and peeking round the trees and jumping out, when I saw something dark move just ahead. I shot it before I even had time to worry.

I had not accounted for how loud the shot would be in the still air, how much the force would shock me backwards, how the jolt would hurt my shoulder. After the shot everything seemed to go really quiet, all the birds shut up as though they thought they might be next, and I ran over to where the thing was and got on my hands and knees by it. I was amazed to have even hit it because I had been knocked off balance by the force, and because I had only been half-truthing when I told Stan and the bus driver that I knew how to use it. It was very dead, which I was glad about, I did not want to see it half dead, twitching or whimpering.

I had never killed a thing before and had made a pact with myself to be stoic about it, not to drop the gun and stare at my hands in horror, all ‘what have I done?’ But as much as I wanted to make it a point of pride not to cry, because a Mountain Man would not cry, certainly, I cry very easily so of course I burst into tears.

When you are a young child you cry for yourself, you cry for the attention of your parents. Growing up is feeling for the first time for the outside world, it is evolving out of your juvenile solipsism (if you are a girl anyway). I remember the moment it happened to me for the first time clearly. It was when the Columbia rocket blew to pieces over Texas on re-entry.

It was a really sunny afternoon in England. I was in the car, sat in the back behind Dad, so it must have been a weekend because I was school age. They announced it on the radio. The radio presenter’s voice was all choked up. I looked up at the bright blue sky, where there was an airplane making candyfloss trails, and I cried. They played David Bowie’s ‘Space Oddity’ on the radio and I felt like I was mourning the Columbia rocket with the whole of the rest of humanity. I remember my dad’s eyes in the rear-view mirror. As I remember it he looked moved, misty-eyed, to see his young daughter cry for the first time at something so outside herself.

So girls as a very general demographic cry more. Maybe you can say this is weak. Or maybe you can say that it takes a lot of strength to admit you feel so much all of the bloody time. Like how our pain threshold is higher from tidal womb pain.

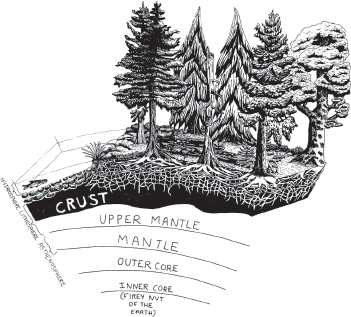

I recognised it from my fauna and flora book as a large snowshoe hare, its blood all stark on its side and in a little pool beside it. It was pale brown and looked paler in a different way, from its loss of animation. My impulse was to cover it with dirt and leave it be. It affected me greatly to think that the blood had been making its way to its heart moments before and now it was outside it, going sticky.

I felt myself shaking, like all my feelings had turned to energy, buzzing around my body instead of turning into something I could understand. It felt like that with no causal link. Before there was a brown hare and now there is this corporeal object. The object is still and cold and looks like a hare, but different.

What is a thing? Is it a different thing without the essence that makes it what it is? Is an essence a soul? Before it was a hare and now it is a body and soon to be a piece of meat. This is why I have to do this thing that I am apparently going to find very disturbing. I need to know that I have it in me to live by acknowledging that I am living where living = not dead. And again for that intangible thing this authenticity, for the documentary.

Back at Stan’s I shot a video of him skinning, and I have it to watch back on the laptop. He said something snide about it but I really do not see the problem. I have never known how to do it because I have never lived in a place where I have had to learn, and it annoyed me that he was being smug when I was trying to rectify this.

The first thing to do (I will gladly be the oracle because I believe in communal knowledge) is to squeeze the animal’s bladder area, for obvious reasons. Then you make a little V shape at the top of the breast to get the knife under the skin, and you cut right down its belly. When this opens up all the bits are just there like you have unzipped a purse full of guts. I have only gutted fish before and it made me feel unusual. I was expecting lots of blood to spurt out and it all to be chaos and mess but it is not at all. You let a little blood out then it is neat, as if the hare was made just for you to eat it.

When the belly is open you just pull the guts out by running two fingers from top to bottom, which is a very odd sensation, and I don’t think I will be able to get the smell off my fingers for days. Then you take off the legs and head; without a meat cleaver not as easy as Stan made it seem. After that you take off the skin, disconcertingly easy, just like pulling a tight sock off apart from a few places that have to be picked apart with the knife.

You are left with a naked, headless, pawless thing, which then needs the remaining entrails taken out, including the duct the poo goes through, which made me feel kind of embarrassed for the hare. I did make a bit of a mess of things but still did well for a first time, I think. I cut it into three pieces, two to keep inside the Tupperware box covered in the salt I brought, and the other to boil tonight then take off the bone and eat with some form of vacuum-packed carbohydrate. I made a fire pit for the guts and set them on fire because that is how you make sure the bears do not smell them.

I had to stop myself from using up too much of the antibacterial hand rub to get rid of the death smell on my hands. I am going out to get some firewood and then I will cook and after some reading I will be very ready for bed, I am exhausted after not sleeping last night. I feel very resourceful. Like a bird must feel when it settles into its nest that it built with its own beak and claws. Birds must be capable of feelings of sorts. When a little bird settles down into its self-built nest and fluffs up its feathers and burrows into its own neck, it is the very image of immense satisfaction.

My plan is to make my map over four days. I already have my rough diagram but need to walk to each place to hone it and add finer details, like where is good for a lookout, or somewhere to maybe practise trapping. I want it to cover the area I am likely to use on a regular day so I will walk for half a day then turn back on myself. On day one I will head north, on day two east, and so on. I think I can walk about twenty miles in a very long day, so the map should cover approximately ten miles in radius from the hut at the centre.

Stan criticised Chris McCandless for the fact that he did not have an official map. If he had had an official map he would have seen that just downriver from where he could not make his crossing back to civilisation because of floodwater and subsequently ate the potato that killed him, there was a pulley system for transporting things and people across safely. But if Chris McCandless had had an official map, it would not have been his wilderness and he might as well have died anyway.

I am not in danger of that because I know exactly how to get back to the road to get the bus back to the visitors’ centre, and I also have radio contact if I want to turn the thing back on. It would not take them long to find the cabin if they needed to, because they know I was headed out without camping gear. I am conceptually isolated and alone, but in trouble I could radio Stan for help. Although I had thought about going further in and leaving the radio behind, finding somewhere else to sleep. With each day I feel a little more certain that Stan will try to rescue me. Actually I am thinking about it a lot.

South of the hut the forest becomes dense and backs all the way to where the mountains start, in the south and arcing west. In the lower foothills the trees stop growing from the altitude, then just behind the mountains rise higher and are sooty black with stripes of white where the meagre snow is. Further behind still somewhere is Denali, the highest point in North America.

Mount Denali was until very recently named Mount McKinley, and is still called that by some bitter Ohioans. It was called Denali from the Koyukon-Athabaskan Deenaalee, which means ‘the high one’. The Russians, when they owned Alaska, called it Bolshaya Gora, which means ‘big mountain’. Then an American gold prospector came along and called it McKinley, which means ‘President William McKinley’, bequeathed in a curious naming ritual used by colonising white men whereby the conquered entity is named after the conqueror or an adulated public figure.

The gold prospector called the mountain McKinley because William McKinley was a proponent of the gold standard and the prospector wanted to get one over on the silver miners, who wanted the president to be William Jennings Bryan, the proponent of the silver standard.

Then President William McKinley was assassinated by an anarchist called Leon Czolgosz because he was the ‘president of the money kings’ willing to exploit the poor to benefit the rich. So the name got officially etched into all of the maps in President William McKinley’s memory by the American government in 1917.

Years and years and they will not stop arguing about it because for America Alaska is still very much in the process of construction. Alaskans want the name to be Denali from Deenaalee, maybe mostly because they do not want to be out-Alaskaned by the Ohioans, who keep blocking the change because McKinley came from Ohio and they want their namesake on the biggest mountain in North America. In real life in Alaska people mostly just call it Denali. The Athabaskans never stopped calling it Deenaalee and maybe do not know what all the fuss is about, because they did not draw maps.

In 2015 President Barack Obama officially finally changed the name to Denali to show honour, respect and gratitude to the Athabaskan-speaking people (as if naming is owning and he was giving it back). Donald Trump declared this ‘an insult to Ohio’ and vowed to change it back, so let’s see how long that lasts. Does an orca care if it gets shunted from one entire species to a separate species dependent on how it hunts (which is what Larus said may be the case)? Probably the Athabaskans just shrug and say you do what you want, we are going to just carry on calling it Deenaalee under your shouting chins. The orcas say yeah, whatever, we are just going to carry on swimming and flipping seals or not flipping seals.

The tundra is always in soliloquy. Mostly it whistles and sings, but now and then the wind will die down suddenly and in the utter silence and still it feels like you are on stage. As though you did not know there were curtains until they just suddenly opened. Then the cacophony of noise again like applause.

From where the tundra and taiga meet you see right across to the east, but you do not see the road because it is too far. The sky was very blue and clouds dragged shadows over the tundra, dimming the glare of the lake.

In the forest I worried about getting lost, but heading due south-west by the compass, towards the steeper foothills, I stayed on track fine. In this area the trees were dense. This route leads to a perfect fishing spot, where the stream is shallow enough to cross and brimming with fish. I headed further on past this in order to get to the foothills because I wanted to climb past the timberline to get a better look. The ground started to slope and the trees thinned so that I had a slight vantage, and I could see what I took to be a radio mast just a mile or so away in the east. I headed there instead for no reason other than that it intrigued me.

The radio mast is really a fire tower. The foliage around it is thick overhead, and after going back into the thicker trees I could not really get a view of it until I was almost directly underneath. There was a little clearing, and when I came into it the sudden view of the tower shocked me. A radio mast was benign in my mind but a watchtower reeked too much of people. It isn’t that I am hermitised already, just that I do not want to lose this game I am playing with myself so soon.

I hid back in the trees, where I was sure I could not be seen from above, and hunkered down to watch for movement in the lookout at the top. In real-life terms, I was also concerned that a park warden might ask to see my permit. Stan gave a resident permit from lost property to me, which he advised me to leave in my hut on the days I went out; that way if anyone dropped by they would leave me be thinking I was ‘P. S. Aldridge’. He did not actually explain what I should do if I met a warden while I was out, he just told me that where I was going was so far away and off-trail I would not meet one at all.

I stayed still, hunkered and watching for a good ten minutes. The tower was rusted and wind-battered. As I watched it, it gradually changed its appearance, began to seem hollower as its potential to expose me withered. But then the fire-watcher could just be sat where I could not see them, reading or sleeping or watching for fires. I decided the only way to know was to yell up. I would yell like some kind of animal from inside the trees and see if anything changed.

I yelled stupidly. Only crows noticed, lifting off from the tops of the trees and cawing at me because they were annoyed at themselves for startling so easily. Then I felt less stupid. Nobody came to the window.

At the base of the tower, with my foot on the ladder, I shouted up again just to make sure. This time, in a human voice, I asked hello? Nothing. The steps were made of sheet metal, like the steps to a lifeguard’s chair, and were rickety. They wound around the four legs of the tower in an angular spiral.

Towards the top the tower groaned against the slow wind. I came into the lookout through a trapdoor. The floor was coated with a coarse gristly dust, prints left where it came away on my hands. Apart from my marks it was print-less. Nobody had been up there for a very long time. I clambered inside and crawled to sit with my back to a wall.

There was nothing inside and the glass in the windows was grimy. I looked around for a sign for when there was last a person in there. The dust was felt-like on the floor. Light came up through the boards, rendering all my movements gold-dusty and ethereal.

I had the thought to maybe check the walls for some kind of graffiti. I imagine they turn up all over the place in spaces like this. There were two; they read:

Johnston Wills, 1952

P Harris, 1999

If I had not found them I could have been the first person to set foot in there since whenever I wanted to imagine. Maybe not objectively, but that would not have mattered. Like how a scientific discovery is a discovery until a new discovery is made that refutes the original one, like how Denali stays Deenaalee to the isolated Athabaskans, who choose not to read maps. Really in this way no one ever discovers anything, they only invent things (we invented nuclear bombs but we say we discovered them because that sounds less evil). I could have invented this place as an unpeopled wilderness for myself. I sat down cross-legged and looked at them and wondered if maybe P Harris had thought the same. Maybe he wrote his name in defiance: you can’t have this place all to yourself, Johnston Wills.

Then I remembered the rock in the Greenlandic tundra that stood to hold me and Urla and Naaja until enough rain, time and rock plants had eroded our names. I wondered what they were both doing right then. If Urla had really thought Larus and I were close in the wrong way, if he let her think that, if she hated me.

If I came back with supplies I could camp out in the tower for a few days. I did not want to cook any food and use the portable propane so soon, so I would have to bring it already cooked and cold. I only have one kind of container for bringing it so I could do maybe two nights if I filled the tub, before I got hungry again. I was brain tired, and my legs ached, and it felt safe to be so high up off the ground, rocking gently, a bird in a tree. I thought of all the canopy creatures; bees in hives, pine martens in tree hollows, porcupine sat in branches, everyone safely elevated from the prowlers, a hovering biome. I felt a comfort like fellowship, and decided to stay put until the morning.

In my dream I am sat at the bottom of the mighty Mekong river talking to a giant catfish, who tells me he is one hundred years old. His eyes and scales are the same dirt-brown as the river, like over time the dirt that settled on him crawled underneath his skin and became his skin. His voice sounds like bubbling custard. All the dead men that fell in the water in the Vietnam War had sheened themselves with DDT to keep mosquitoes away. Agent Orange collected in the waters and the soil and the bodies of the living things.

The bodies got eaten by the little fish, bigger fish ate the little fish, the catfish ate the bigger fish, all the DDT and Agent Orange from all their livers built up and up in the liver of the catfish. Now the catfish is poison. A hook and line plop and sink into the brown river to where I sit with the catfish. He takes the hook in his crêpe-like fin and pops it through his blubbery lip. Above, a little Vietnamese boy reels in his dinner.

I was sleeping deeply and was jerked quite suddenly awake by a strange, long noise. A bell. I shook all over and my teeth clanked from panic. I imagined looking over the spruces like a crow sees them, stretching on and on, an unbroken sea of green and dark shadows. And then the tower.

A bell needed somebody to ring it. From a vantage of anywhere over the forest, from the ridge or the semicircle of higher ground from the north, you need not be a crow. Had I lit the tower up like a beacon when I used the torch? Somebody had rung a bell.

I sat up when it came again, peeling away on the wind. It sounded distorted this time. Then right away, it came again. Only this time it sounded nothing like I thought it at all. It was unmistakable: a mournful warble as timeless and familiar as the pentatonic scale.

I grabbed the camera and scrambled to open up the window and look down into the dimly visible clearing. It was empty but the wolves were near. The howl had come so clear, and besides I could feel them. The forest was heavy with anticipation, the spires of the evergreens whispering like a crowd as the lights dim.

The howl came again, and it went right through me, could have been in the tower. It made my whole body shudder in a way that made me grin; a tingle of pseudo-fear like looking down from an airplane. My hackles raised of their own accord. Into the clearing came a dark shape, one, two, three, and then a white one, then one more black. They fanned around the base of the tower with their noses to the ground. I could hear an excited kind of whimpering.

Wolves are an animal I can trust. Their packs are hierarchical, but they are spearheaded by a male and female breeding pair, who rule together in equality. Wolf Wives are absent from The Call of the Wild. Two she-dogs are friendly so get killed, and the only strong female sled dog – Dolly – goes mad and has her head smashed in. Mercedes, the sole female human character in the book, spends her cameo crying and complaining. This has left a lasting impression on men-who-think-like-dogs like Stan.

For a moment of delicious fear I toyed with the vision of the wolves staying put and waiting for me. Sitting on their haunches and looking up at the tower with hungry eyes.

But they did not look up. One of them cocked his leg to the tower then yelped, and they filed away quickly into the trees with such a purpose I knew I would not see them again that night.

When I returned to the cabin I was glad to find everything as I left it. My permit was in the exact same place on the desk, so I am pretty sure nobody came by. I will go back to camp in the tower at some other point but I need some proper food and my mosquito net. Stan was smug when he added it to my list and I had thought it an arbitrary appendage to make him feel like he had had one on me. I have to give him credit now as actually I would have been fucked without it. In the tower so high up they were not so bad, but in the cabin and outside on evenings they come in swarms. I can slap my arm and kill four at one time. I feel a little bad doing this because I know that only female mosquitoes bite and they have to do it to get enough iron and protein to make their eggs. They are only trying to feed their babies, just like everything is trying to feed its babies.

I decided to try fishing as I figured it would affect me a lot less than shooting a thing dead. I had bought some fishing line and hooks in Fairbanks, and for the rest I found a sturdy stick as my rod and tied the line to the end, where it splayed, so I could attach it around the adjoining part to make it more secure. I made the line long enough so that I could yank it out the water fast, but with no reel I can only use it in relatively shallow water.

I was stumped for a float until I remembered a redundant tampon at the bottom of my bag that I’d brought just in case I lost my Mooncup. It was still sealed with all the air in so it worked a dream. I attached this to the middle of the line before tying the hook to the end with a little ribbon of foil from a noodle packet just above it to act as the little fish-attracter thing. Then I upturned a log and collected myself some grubs and worms for bait in a rusty tin can.

I found salmonberries (they look a little like raspberries, more seedy and juicy) and harvested as many as I could carry inside a clean sock. Along the way I managed to find lots of dandelion leaves that I washed in a stream and nibbled. There was also a plant I came across that looked like the plant the pamphlet called goosetongue, but it warned that it also looks like arrowgrass, which is poisonous. I have learned enough from Chris McCandless to know that eating anything I was not sure of would be a no-no, but it felt wholesome to be learning the things by their names just to look at and touch, their tactile truth.

Although to be fair to McCandless it does not seem he confused a lethal plant for another, it was just his own fauna and flora book did not tell him that this certain potato he was always eating actually contained lethal toxins. It was a taxonomical failing and not ignorance that killed him, as I said to Stan.

The course of the stream widens out where another joins it. The water runs clear and shallow; underneath it you can see the shadows of the fish holding themselves against the current. They hold then dart away suddenly for reasons kept from you by the mirage-making surface. I watched one fish that seemed to enjoy holding itself against the exact point where the two waters met and did not move from this meditative state for a whole fifteen minutes. Do fish feel meditative? Without awareness, just some primitive state of tranquillity?

I set up the rod to dip into the water where shadow from the trees hung over. The forest was awake to me and gave its alarm call. I made sure the rod was wedged into the ground firmly and rested my leg against it so I could feel any movement. It is like all my senses are intensified, sounds are so loud they make me jumpy and my body reacts nervously to the slightest movement. I feel like an acrobat, every body part accountable for something.

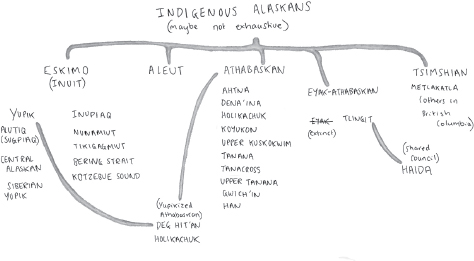

After not too much time the birds took up their usual quarrels with each other and ignored me, and the sound came thick from the trees. For some time I lay on my side with my ear to the cool, damp ground. I could feel how far down the layers of earth went below me like vertigo, with soil and crust and mantle, lithosphere and asthenosphere, all the way down to the fiery nut of the earth. I could almost hear it, a mellow, churning grumble.

You can’t feel that in a built-up place. In a built-up place the ground is thick with artificiality. In a place that has been built and rebuilt many times over, old towns fallen, redeveloped, retarmacked, returfed, that turf in ready cylinders like grass-and-soil Swiss rolls rolled out, plastered new again and again; it feels too structured to feel dizzying. This is a part of the reason I like my lime quarry so much. All its layers. At the lime quarry the earth is bare and cut open like a quiche and inside the quarry you can feel closer to the heart of the earth, like touching the pit of someone else’s scar.

The tundra is so big and open that animals are exposed everywhere, so they keep one eye on me warily, but go about doing their thing as I walk on past. How crawling with life the rough grasses are. Hares rush around and stand sentry, ground squirrels run in little bursts, stopping to gather fruits and buds in their cheeks. A weasel slinks through the grass after the voles, so frantic to gather food for the winter that they let their guard down. Summers are so short that everything is fighting against time to prepare, the predation of winter overshadowing that of everything else.

In Britain we used to have wolves and bears and lynx and bison and even elephants and rhinos a long time ago, but we are such a tiny island that we quickly killed them all and became kings of our little kingdom. Accounts for some of our colonial hubris?

The tundra is specked with water where the frost melts. The permafrost lies underground, starving the drier parts. Lusher grass surrounds waterholes, and elsewhere the grass is hardy and coarse and shrubs are dead-looking. It gives the tundra muted but multifaceted colour. The way the light plays on it from the big sky makes its depth and tone flicker.

As soon as I felt a tug I jumped up and had it over my shoulder before I even knew it and I am glad no one was around to see because the force from flinging it back brought the fish back at me and it hit my front as I turned to it, making me yell. The sound zigzagged away from me into the forest and took several birds with it. It took me a second to remember that there was no one around to hear, but when I realised I was alone, so utterly and completely alone, I laughed and laughed to myself, trying to hold the writhing fish.

And I could feel all of Jack Kerouac’s ghosts of the mountain cursing at me for desecrating the art. But if the art is to demonstrate skill rather than a simple utilitarianism then I don’t want to be a part of it. It is a man’s sport, a battle just to collect its name, possess its specificity, like the Enlightenment exotic specimen collector (one for the collection, a big one for the wall). And to do so skilfully, whatever that means, probably with minimal splashing and squealing. They can keep their art.

Once I had it still against the ground I had to stun it to knock it out before I bled it, like Larus showed me on the pilot whale boat. I worried about this part because perhaps it did have more culpability than pulling a trigger and watching a thing drop. The fish lay still for me, looking up at the sky through the canopy with its empty orb of an eye. I have thought for a long time that anything I am willing to eat I should be willing to kill. And although I back the philosophy all the way, in practice it is as hard as I hoped it wouldn’t be. I am not sure I will ever be able to kill anything without crying at least a little bit.

After it was bled I laid it out flat and took out the Fauna & Flora of the Denali Wilderness book to identify it. It was an Arctic grayling, I could tell easy from the fin on its back like a Chinese fan. It was quite little for a grayling, but I can make it last me two meals.

In the tundra I stumbled onto a spruce grouse sat on a clutch of eggs. It occurred to me that I could take her eggs to eat. She looked at me imploringly through one beady eye. I left her.

Osprey

American kestrel

Pintail ducks

Snow geese

Tundra swans

Ring-necked ducks

Grey jay

Horned grebes

Plovers

Mourning doves

Cuckoo

In the south the mountains stood resolutely, still and intangible as a painting, until at one point a light aircraft cut across them, a slow and deliberate finger through perfect dust. When this happens there is a noise with it, a loud droning that I noticed for the first time while watching the first plane. It was lucky that I did because I might have spooked from hearing it without knowing what it came from. I threw myself to the ground on impulse but it was too far away to make me out. From here you could not tell the cabin from the treeline.

On the way back to the cabin I found my first bear print. It made my hairs stand on end; a first encounter. Its print a symbol of its self. A warning, a promise, a truth. But really it is just an imprint a big animal left without meaning to. How strange.

It confuses me to have nightmares about a thing I can barely remember now. I had thought it over so many times before that I could no longer tell what was memory and what got added or taken away. Then I stopped remembering it at all, but it came back last night in a bad way.

In the nightmare I found myself cold and dark. I was in an ice cave. In the Arctic. The walls were blue and jagged. It smelled like damp old fish and dead things. My breath billowed in silvery wisps in front of me. Then it would crystallise and fall to the floor in tinkles. On the back of my neck I felt my hair brushed to the side and hot sticky breath ran across it slowly. A hand came from behind and clasped over my mouth, a stubby, sweaty troll hand.

You are not in an ice cave. You are in the meat fridge at work. The hand is clasped tight over your mouth so your whimpering is muffled. The other hand fumbles with your small breasts over the top of the polka-dot starter bra your mum bought you because you are starting to blossom now. You can feel something hard pressing into where your thighs meet the crease in your arse. You know it will make it worse if you squirm but you want to get free. Then you get a chance because someone shouts at him from outside the fridge, his grip loosens and you dig your elbow into his bloated troll belly.

He grunts a troll grunt. He puts his hand around your neck and calls you a little bitch. But then you know it’s over because she is shouting to him from the kitchen. He lumbers to the door and as he closes it he leans his face in and runs his tongue over his fat wet lips. The door bangs shut.

You can’t cry you can’t cry you can’t cry because they will shout and send you home, and then what? If you yell Sandra will hear eventually and she will open the door from the outside and let you out and laugh at you for being scared of the dark and getting yourself stuck in the fridge again.

Was it as bad as the dream felt or was the dream just a collage from things the other girls had told you? No matter what you remember, it is nothing special, of course. Almost every girl you know has a troll to remind her that her body is not her own.

It tipped it down today so I stayed cooped up inside. The cabin is cosy with the little fire going, the tapping on the roof and sides adding sound contours that make it feel particularly safe, so I felt better. Because I had the time I made the fire with sticks from my kindling pile. I am very proud of the fire. It took me about ten minutes to get smoke, then another five to get it going properly. I have guarded and fed it all day like a little pet. Kaczynski complained in his diary that he failed to consistently make fire without striking matches and that it annoyed him greatly. I am more authentic than Ted Kaczynski!

I did go out just to see how bad it was and got a headache from the hammering of icy raindrops on my crown. It was too heavy to see much and I got soaked through, so I will have to stay put until it slackens off. I have enough food to last and a bit of fish. Hopefully it will have stopped overnight, though.

I watched back and edited a lot of footage and it is coming together but in a way I am not quite sure about. Mostly when I watch things back they do not feel like I remember them. People seem to be very different to how they really seemed at the time. There is so much responsibility in putting the pieces of what has happened together to follow a story. And there is Rochelle, who will not fit into my story. And then there are the things that can’t and do not say anything at all and lie vacant for my projections.

Am I pulling them out of the water like fish to look at? Like they are specimens and I am writing them into my field book? There is a gap between what they are and what I think they are and I am trying to talk about this gap with authority, declaring I know what I see and it is this.

I did a lot of reading. Then I did a video diary entry. Then I got bored and decided to search around the hut for hidden things. I had figured it must be at least fifty years old, maybe even one hundred. I had not bothered to check it properly for signatures like I had the tower, aside from a quick sweep. I felt sure I had missed something.

I checked all the obvious places again first, the walls around the cot, the desk with everything taken off it. Then I found them in a corner of the room. Now I have found them I do not know how I did not notice them before. It was not an obvious place, sure, and most are really faint, but there were enough of them. They are mostly names and dates, the earliest being 1929 and the most recent P Harris again, 1999. I counted seven authors of six signatures and five quotes. Some of the classics:

‘Going to the mountains is going home’ – John Muir

‘I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived’ – Thoreau

I checked, out of curiosity, behind the fox head (there is also the compulsion to leave a mark that no one will ever notice). It just said Caroline, in very tiny print, with no date. It was the only obviously female name in here. Even where the names were ambiguous, the handwriting on the wall was all very masculine. What I mean by this is that maybe the men who wrote on the wall had learned to express themselves as men, to express their man-sized ideas in a handwriting that was reflective of how they held and thought of themselves.

Because they author these ideas like they belonged to them by virtue of being men. Thoreau and that bunch always talked, of course, in lofty terms of Man and He. In search of some inspirational wilderness quotes from women before I started the documentary most to be found came from low-brow memoirs of the self-help kind and had to do with inner journeys rather than the outer objective Truths of the Mountain Men, and had titles like The Single Woman: Life, Love and a Dash of Sass or Pink Boots and a Machete: My Journey from NFL Cheerleader to National Geographic Explorer.

I wanted Caroline to know, if she ever came back, that I liked that she had hidden herself. I drew a little smiley face next to  her name.

her name.

INT. CABIN, AFTERNOON – Erin is sat on the cot – daylight bleeds inside, casts light over dust motes – camera is hand-held – in shot are cabin cot, Erin from shoulders up, and window – it is raining heavily –

ERIN: So this morning I found something really interesting.

After the autograph wall that I found yesterday. And the signature behind the fox head. I was sure there could be other more hidden things but I wasn’t sure where else they could be. I was actually under the desk—

– camera view turns towards the desk as Erin gets off the cot and directs the camera to it –

ERIN: As you can see, there isn’t anything there

– camera sweeps the underside of the desk –

ERIN: But. In checking under the desk I found something else. If you look here—

– camera view turns to the floor – Erin is kneeling, her right knee moves against the floorboard, which gives – the opposite end of the board rises, around one inch – Erin prises underneath with her free hand –

ERIN: Oh. I can’t do it one-handed

– camera is placed on the floor –

ERIN: And underneath. I hadn’t thought to check under the floor because I was sure there was just the foundations underneath there. But here, as you can see—

– camera is picked up and view is directed towards the floor – the floorboard now removed and placed to the side – camera takes two seconds to focus in low light –

ERIN: Someone has dug out the ground underneath the floorboards. And they have left a little parcel

– camera is now in focus – in the hole there is a package wrapped in tarpaulin, about the size of a shoebox – Erin takes the package out of the hole –

ERIN: Isn’t this exciting? So I found this little package. And now I suppose I should open it

– camera is placed on the desk with a view of the cot – Erin sits cross-legged on the cot with the package on her lap –

ERIN: It’s like Christmas

– she looks down at the package with her hands placed on top – pushes hair behind her ears –

ERIN: I’m kind of nervous. I hope it’s not a letter bomb

– she looks at the camera – pulls one corner of her mouth down in mock-nervousness –

ERIN: Okay, then

– she starts to unwrap the parcel – carefully, particularly –

ERIN: I wonder how long it’s been down there

– having undone the parcel string and peeled away each corner of the tarpaulin she takes out a fabric bundle – she carefully unwraps the fabric bundle –

ERIN (ABSENTLY): I suppose they wanted to make sure it kept dry

– inside the fabric bundle is a parcel wrapped in newspaper –

ERIN (ABSENTLY): It’s like a game of pass the bloody parcel

– she stops with a piece of the newspaper in her hand – studies it –

ERIN (ABSENTLY): Oh, I’ll check afterwards

– she lifts the objects from inside the paper one by one and lays them out on the cot very carefully –

ERIN: Okay, we have a roll of paper. A book. It’s maybe a diary. A folded piece of paper. Some postcards from Alaska

– she picks up the book and opens it –

ERIN: It’s a diary. The first entry is dated the 14th of May 1986. It’s signed Damon. Then inverted underneath. Nomad

– she brings the book towards the camera and holds up the name, pointing with her forefinger – in spidery handwriting DAMON is written, then backwards underneath its mirror image – DAMON –

ERIN: I don’t know if that’s an alias or just a happy coincidence. Or a self-fulfilling prophecy

– she sits back on the cot and picks up the scroll – unscrolls it –

ERIN: Okay. This is a manifesto. I won’t go into it now. We’ll look at it in detail later

– she studies it for a second then turns it to face the camera, holding it closer for inspection – then she turns it around and considers it again –

ERIN: Some kind of Ted Kaczynski manifesto

– she carefully rescrolls it and places it back on the cot – picks up the folded paper –

ERIN: And finally

– she unfolds it and pauses, brow crumpling – studies it for seven seconds –

ERIN (ABSENTLY): Damn it. I should have known it. (REMEMBERING THE CAMERA) Erm. It’s a map. Predictably

– she frowns at it some more –

ERIN: It’s better than my map (LAUGHING). Goddammit

– she folds it pedantically and tucks it into the back of the diary – she places the diary back on the cot – she sits with her hands in her lap then distractedly places the newspaper over the top of the diary –

ERIN: That’s exciting. What an exciting find

– she looks directly at the camera, holds her gaze for four seconds – fidgets –

ERIN: I’ll have to take a look at it all in more detail. Figure out this guy’s story

– she touches her face absently –

ERIN: Try and figure out if anyone found the package before

– she twists her hair round a finger –

ERIN (ABSENTLY): Yeah

– she stops twiddling her hair and stares into space, caught in a thought – five seconds – snaps out of it –

ERIN (SUDDENLY/BRIGHTLY): Anyway. Today is day three of the floods and the rain is still relentless

– looks out of the window –

ERIN: Doesn’t seem like it will subside very soon so no meat for Erin for a while. I’ll have to get outside today, though, because I’m almost out of water. I’ll wear my anorak. It will be nice to go outside. Yes

– she sits for a few seconds looking out of the window then snaps to – approaches the camera –

ERIN: Okay. Over and out. (MUTTERS) That was stupid

– she fumbles with the camera to cut –

I attempted a video diary entry and retook it about five times. None of them seemed right to me. I am thinking about how far I have come now and whether I am passing Leopold’s test yet. I certainly feel more ‘in tune’ with the ‘rhythms of life’. It is hard to talk about something so personal and unspecific. I was shooting a sequence on the map that was in the parcel. In the first cut I was saying that I had to burn this map too, like I did Stan’s pocket map, had to burn it as quickly as I could before it embossed on my mind and corroded the claim of pure invention so that this place could still be mine. Then when I had the lighter to it I just could not do it. And the more I held it out with my thumb, scratching at the friction wheel, ready to light it, the more I looked at it. And the more I looked at it the more it embossed on my mind. Then the integrity was gone anyway so I figured I might as well not burn it. My thumb hurt from rubbing and rubbing the lighter without actually striking it.

So then I had to soliloquise about why I was not going to burn the map. But the map glared at me, making itself more and more familiar, and as I got madder at it I thought that I might still get rid of it like I did the other map, because I had seen that one too. Besides I could not just leave it, knowing it was so heavy. I mean like the heaviness you must feel when you find Roman vases in the dirt and you just know that they are not any old broken pottery because you can feel their heaviness from just looking. I had to acknowledge it, like holding a tiny funeral for a mouse that the cat brought in because it does not feel right to just let it be.

But Damon had made it and it was his time capsule and yet he would never know any better. And then again he left it here in the eighties and he could very well be planning on coming back for it one day. Maybe he really never meant anyone but himself to find it.

So I could not burn it. I had to put it back in the ground and pretend I never found it. I left out the diary and the manifesto for now because I need to study them. I do not think there is hypocrisy in this. He will never know I read the diary and the manifesto wants to be read and the map I could just try to forget.

A thing I did notice is that our maps are different. He marked different features on his to those I drew on mine. He marked some that I have not found, and some of mine were missing. I just have to be careful not to let seeing his infiltrate on my personal wilderness.

INT. CABIN, MORNING – Erin is sat on the cot – camera is on desk opposite – in shot are cabin cot, Erin sat cross-legged, and the window – it is raining heavily still –

ERIN: I have been sat inside the cabin for five days now without leaving except to use the toilet. The rain is relentless. I have been thinking lots about what it’s like to be alone for so long. It feels like right now the whole experiment is being intensified because I am not even outside and around nature. The only time I am solitary really is when I am inside alone. This is the biggest test

– her voice is low and sleepy – she yawns –

ERIN: It’s just me, myself and I

– she frowns as if she does not know why she said it –

ERIN: Oh, that was stupid. Reshoot

– she stares at the camera long enough so that she can cut out the first part in editing and begin talking as though she were just starting –

ERIN: It has been raining now for five days and I have been isolated inside the whole time. I don’t have much stimulation in here apart from these guys, who are sort of helping

– she nods to her pile of books –

ERIN: I can pretend we are in conversation. In here I don’t have nature to make me feel small. I am surrounded only by all this male intellect. It is the only thing that stops me from disappearing. But it is maddening because their words are not mine. They keep reminding me that. The wilderness is not mine. And at the same time it is all I am. I keep thinking zone of middle dimension. I keep thinking, okay, Newton

– her eyes keep darting to just next to the camera’s eye – she touches her face and hair, as though she is looking in a mirror, checking reflection – the viewfinder of the camera is probably turned towards her –

ERIN: I am so wholly excluded from the communion. And without being outside all I have is these abstracted unattainable thoughts on nature. Why the fuck am I even reading this. URGH

– she throws Emerson across the room –

ERIN: Am I doing it right? I need to get back outside

– she pauses then exhales suddenly through nose – puts face into hands – sits still, rubbing her eyelids with her fingers –

ERIN (TO HERSELF): Maybe I can’t do this. Will the spirit of the mountain disqualify me for wishing I just had someone female to talk to? Is a lone bird on a tree on a lonely mountain singing to itself? Oh, for fuck’s sake. Reshoot

– she rubs her face with both hands – slaps her cheeks – takes a deep breath – looks right into the camera –

ERIN: It’s okay to not be content one hundred per cent of the time. Right, mountain spirit? If it were easy then it wouldn’t be hardship. And maybe it’s right to feel lonely. I can do this. I am strong enough to do this. This is the hardest part. The rain will stop soon. The only time I am lonely is when I am inside too long. Besides. I am not lonely. I have the camera and my books

– her resolute smile lingers and then fades –

ERIN(MUTTERING): Oh, I can’t use that. This is useless

– she gets up from the cot and reaches over for the camera –

I am confused about the postcards in Damon’s parcel. The postcards are written in Damon’s handwriting but are addressed to different people at different addresses all across North America, Canada and Alaska. They are all dated September 1987 and are all of the same kind of sentiment. Damon is thanking people for their hospitality, help and friendship. He is telling them they are beautiful people with room for improvement. Then he is telling them they can improve by living for themselves. He is telling them to cast off their chains and live like he will live, purposefully and free. Then he ends with an ostentatious phrase about casting out into the unknown. He insinuates that they might never meet again.

I suppose this is what he would have liked to say to these people, as though they were parting words, but something stopped him. The strange thing is that the postcards are stamped and bent at the corners and marked like they have travelled. I think maybe he did more than one journey like this, and he brought them to the cabin with him as some kind of token.

It is still raining. Last night I had the epiphany to leave out one of the cooking pans to fill up with rainwater so I did not need to venture out to get water from the spring. The rain battered against the hood of my anorak in a way that was exhilarating, an overload of stimulation after endless days inside the muted dry. I ran about in it yelping and laughing for a few minutes before retiring back inside like a fish that comes out from under its rock to dance a little in a flurry of excitement then catch itself and slink off back into the shadows. It was exhausting and after I wanted the stillness of the cabin again.

Inside I peeled off my anorak and my sodden leggings and hung them up next to the grate. Then I coaxed a fire and set myself on the cot in view of the pan through the window, with my books. I quickly forgot about the pan, though, and did not remember it until late afternoon, when my mouth was feeling suddenly dry. My clothes had dried and I was loathe to get them wet again, so I took off my trousers to fetch the pan in just my anorak. It was brimming with water, with a couple of drowned insects for good measure. I picked these out and put the pot on top of the fire to boil.

I filled my canteen with the boiled water and set it to cool. Then I made a broth from the rest of the water with one of the flavour packets from the instant noodles. I curled up on the cot and wrapped myself in the blanket and my sleeping bag with a tin mug of the hot savoury water. I smelled must from the blanket, and savoury, and me. The little excursion earlier in the day had made me overwhelmingly sleepy. I fell into it and slept for the rest of the day and long into the evening.

I usually like to rise early and keep myself busy but with the rain I have been dead heavy all the time and dull and lethargic, but I wake in the middle of the night and I have an interlude of energy before falling back to sleep again. I use this time to read and write and draw, and wish the rain would stop so I could go night walking. I am dreaming lots again.

A thing I have noticed is that they are all in the present tense. As in I am not dreaming about things from before here, no memories or other people or anything. No one I know, at least. Kind of spectral figures. Familiar strangers.

LOCATION: wooden cabin; Denali wilderness; Alaskan tundra; Alaska; Earth; 3rd planet of Sol; inner rim of Orion Arm; the Milky Way; the Local Group; Virgo Supercluster; The Universe; Everywhere Ever and All Over Again.

The tundra is always whistling. wwwwWWWWWhhhHHHHhhh. The tundra is empty. The tundra is partitioned by colour. There is the green-grey flat ground that I am on, the cabin, then the white-blue mountains. The mountains look like a backdrop. I feel like Truman Burbank.

If I sit still for long enough the whistling sounds like words. Big snowflake tumbleweed rolls just under my line of focused vision. I blink and it is gone.

If I sit still for long enough my eyes go blurry like a mirage. Like heat waves but cold, cold. It is hard to focus even when I blink hard.

Another sound starts behind the whistling. It sounds like a plane; I look around for one. Negative. It sounds like a person humming; I look around for a person. Negative. It sounds like bees. My hand tickles and there is a bee on it. Affirmative. The bee sits happy. I must be dreaming. The humming is louder.

In the shimmery mirage there is a dark shape coming closer. There is a figure in a cloak, furs, beads, skulls and with a staff. Her voice is very strange. I can’t see the features of her face because of the bees, which swarm in a flat mask. As if her face has no shape; no pits, no curves, no nose. It is hard to tell where the sound comes out from. There is a vibration on her voice, as if she’s speaking through a laryngophone, as if her voice emanates from all the tiny mouths of the bees in unison. It gives her what you might call an otherworldly aura. Almost techno-human. Like Professor Stephen Hawking. It is authorial.

Stephen Hawking has a daughter called Lucy and she grew up to be a writer. She wanted to inspire children to get excited about space and physics and all the things she grew up in awe of. She writes adventure books about a little boy called George who likes space. Isn’t that frustrating?

She moves to sit by my side on my log, which does not budge under her, as though she is weightless. I look at her closely and, sure, she has this shimmering quality, buzzing and wavery and nearly not there, like a model of an atom spinning on its axis, just slow enough for you to see the falter, its constituent parts flickering visible. I reach out to touch her and can’t seem to, her contours blurring as my hand gets close, but hovering just above I can feel her. A kind of soft quivering, a pulsating that feels like sound, low sirens in my temples. She draws in the dirt with the end of her staff. The gravelly sound makes me hungry. Like Coco Pops without milk. Her voice has an ungraspable familiarity to it; it is hard to concentrate on what she is saying because of her bee beard.

The circle is the antithesis of the triangle, because the circle stands for cycles which are even and infinite. In the centre of a circle you are always the same distance from the edge.

The ghost of Adam Smith sits on a triangle that is held upright by the shoulders of his crawling subordinates. He is hoarding all the power, and as it grows exponentially, the growth of others is depleted. But as the others are depleted, they are harmed to the point of abandonment (the bees are the first to leave him). As such, he loses his sense of self, which depended on a sense of the others.

So that is where the bees have gone. Around a week and a half has passed since I left Stan’s. I cannot be completely sure because I put a bit of tape over the date and time on the laptop for now and I have spent a lot of time sleeping when I should be awake and waking when I should be asleep. I have been inventing people for company, to talk to and mitigate the loneliness. Are invented people a corruption of solitude?

I have bathed once in the stream in all this time, little splash washes on my smelliest parts now and then. I smell but I only notice this when I take off my pants in the toilet shed. The rest of the time my smell is enveloped into me by my clothes. It worries me when I take off my pants that I may attract bears.

My face itches a lot because I keep touching it; I keep touching it because I think I am growing a beard; I think I am growing a beard because of the itching. There is not a mirror and the camcorder is just illusive enough to make me think I can see hair.

From the bee-figure dream I can pinpoint exactly in my subconscious the fodder for it. Back in the visitors’ centre at the entrance to Denali Park there were displays on all of the cultures indigenous to Alaska. I remember a diagram explaining the position of the individual in the Yupik Eskimo belief system in relation to the animals and plants it shared its home with, termed Cosmological Reproductive Cycling. In the diagram the human was part of a sort of energy transferral web, in the shape of a circle. It made me think at the time of a diagram we had in biology class, a food pyramid used to describe energy transferral in the animal kingdom. On the biggest pyramid and at the top sat the human, the unchallenged dominant omnivore at the top of the food chain.

Adam Smith casts himself as the dominant creature of the triangle and food chain and propagates this as the natural order of things. He eats a mass of lesser creatures who have themselves eaten a mass of even lesser creatures who have been grazing on chicken nuggets and apathy because their natural food source is inaccessible to them (these are the crawling subordinates). All of their power accumulates in Adam Smith. He uses this as an economic analogy, substituting for food or energy wealth or money.

The triangle food pyramid is used to explain hierarchy in nature and justify Adam Smith’s dominance. But it only looks that way because he said it does. The wolf does not sit on top of a pyramid. The wolf is dependent on the grass because when the grass dies the deer dies and when the deer thrives the wolf thrives and when the wolf overreaches the wolf is brought into check by its own hubris because the deer disappear and after a short period of thriving the wolf does too.

For the Yupik, like Naaja’s Inuit, nothing alive died but was reborn, and this was honoured in hunting ritual so power could never be accumulated but only transferred.

The orca and the wolf were seen as highly spiritual creatures that aided humans in hunting, and so offerings were made to both to maintain good relationships. The spirit that resided in each was interchangeable, in winter it was embodied in the wolf that brought the deer and in summer the orca that brought the walrus.

When an animal was killed as prey, it was returned to the wild to become complete again. To aid this, the bones of the carcass remained unbroken, and there was a farewell ritual where the animal would be entertained with drum music. If the animal was pleased with its treatment as a guest, it would return again in the future.

I am surprised Stan could retain his survival-of-the-fittest worldview when spending so much time in the park centre. I suppose he must not pay too much attention to the plaques.

During the night the rain stopped! I woke up to its lack of noise. It took me a while to realise it had not stopped completely. The gentler rain was white noise. I fell to sleep again feeling looser.

The rain was slack still when I woke up and I decided to try some fishing. It has been days since I have eaten anything that is not beige and the urge to get outside was so great that I twitched with it.

Walking through the forest the rain was less dense still. It fell in fatter drops and at a different tempo to the rain as it hit the canopy above. The noise of rain inside the forest was both dulled and intensified, like a storm from underneath a high church roof. It was much more peaceful in the forest and I felt a stillness come over again for the first time in days.

I decided to try out on the lake in the tundra. I had been stupid to think I could just fish from the lake with my shoddy short rod. But lucky for me there was a rock that worked a bit like a jetty and let me sit with my short line in the deeper water. In the still water where the rod dripped, the beads skimmed on top for seconds like water beetles skating, before sinking.

It was luckily an okay spot. It took less than an hour to hook something and I wished I had a way to make the fish keep better so I could stock up and get all the death over in one go for a while. I stunned the fish against the rock jetty, trying to do it without thinking too much. A large ant struggled a tiny caterpillar that was twice its size over my rock and back to its queen. I attached the dead fish to the hook so I could walk it back without having to carry it in my hands. I wiped my hands on some damp grass with lake water to get rid of some of the sticky smell.

When I looked up I went stiff. On the opposite side of the lake there was a bear come out of nowhere while I was busy with the fish. A bloody big grizzly. I forgot my entire body and the rod fell out of my hands and the bear stilled too. It watched me watch it from my plinth on the rock, its fur flittering in the wind. It was close enough to see that but it was still small across the big lake. There was a potent unreality to it. It was still and mysterious in an accidental way and I felt very suddenly that something in me was going to be different from then on.

I put my hand on my chest to feel my heart beating vigorously but it was not. In fact I did not feel like I thought I would at all. Since I had got out to the cabin The Bear had existed like an aura, since before that even on the ice sheet, the Greenlandic tundra. It had felt conspicuous for not being there; lingering like a promise and quivering with anticipation and fear. And I had thought back then that it would feel like opening up, that I would see that Fire burning in its eyes and recognise myself in it. But instead after all there it was so suddenly. It looked so benign and abstract, an apparition. I wondered if perhaps it was.

I want to see myself in you.

But we are very different.

I felt like if I turned away it might disappear, and although some flight response was tugging me gently, telling me to get away, I did not want to turn my back on it. It seemed to be thinking the same of me. I started to think maybe we would be trapped like this for ever, perpetually watching each other watching in wary fascination.

My blood tingled vigorously and I could feel it filling me up all the way to the tips of my fingers and toes, so that the sensation of my feet in my shoes felt like containment, like what it must feel like to be liquid and formless but held in shape, my hands like rubber gloves full of water. Like zero gravity. Like proprioception.

I put one foot behind the other on the rock, using my heel to feel out the stable parts, and climbed down off it without ever breaking contact with its eyes. I put down the rod in case it thought I was brandishing it. Then I started to tiptoe, desperately slow, closer towards it following the lakeside. I was trying to move so slowly that it might not even notice. To get closer to it and really feel its presence. To commune.

I have never felt such an acute kind of instinctual consideration of what it is to not be alive. It became clear then that any nostalgia that we feel from The Call of the Wild is the pang of what we remember but do not have, from where we are before we go in search of it. It is all of the prospects of having life taken and of not being and of things that you can never possess or control or put into words. In that moment I forgot the anxiety of having a body, I forgot the need to possess it.

While I was thinking all this I had got a lot closer and I could feel my heart then where I could not before, throbbing in my throat like a pulsar. I was shaking badly from concentrating so hard on my stealth. The grizzly bear stared at me, transfixed. Unmoved and hypnotic stare. We were both fixed on each other in fear and desire or morbid fascination. Or none of that. Just purely under spell.

But in that way I see me in you, in what I am not.

Then it jerked its head. A sudden lurch snapping the thread that had formed between us. It peeled its black lips back to show its teeth and it jolted me to notice I was so close as to see its teeth clearly. It padded one front paw behind the other, walking its front legs backwards into itself, then using the weight of the rest of its body and jumping a little to bring its forelegs up and stand bipedal, unfolding to its full height and stature. Huge. Fuck.

I could see the matting of its fur where its underbelly was wet. It huffed through its nostrils, short, deep grunts.

What am I doing what the fuck am I doing.

Abruptly out of trance now. I suddenly see myself from right up above, as though looking down. I am small and it is big and the lake is huge blue glass beside us and the grass goes on on on around us and there is nowhere for cover.

I keep absolutely still and try to think. What did the pamphlet say what did the pamphlet say. Direct eye contact. Did it not say never to make – very dangerous. I avert my eyes, lower my head, still trying to see it. Keep one hundred feet between you. Was it one hundred? Five hundred? Maybe fifty. How far is fifty feet? Either way it is too late now. What else? Do not go without pepper spray. Well, that one’s out. It said calm, monotone voice. Let it know you are human.